Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle: (Krebs Cycle / Citric Acid Cycle)

The Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle (Krebs Cycle / Citric Acid Cycle)

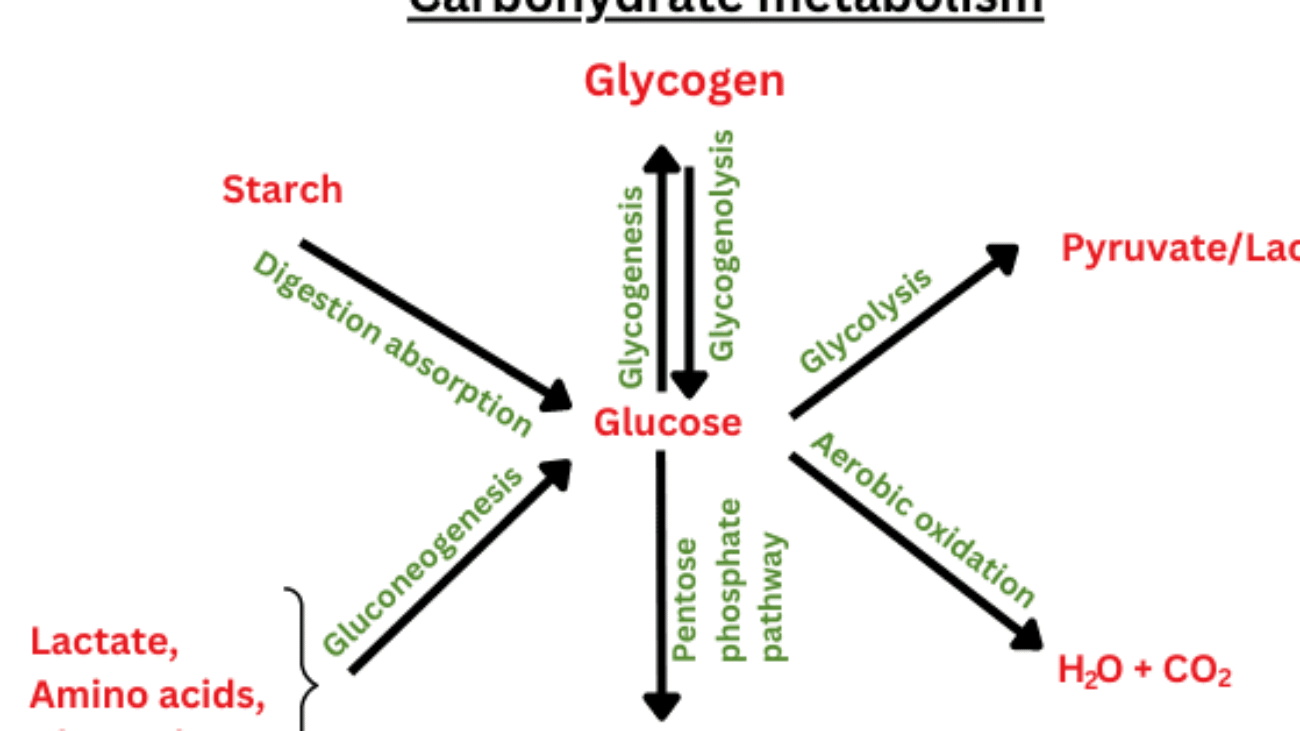

The Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) cycle, also famously known as the Krebs cycle or the Citric Acid Cycle, is a central hub of metabolism. It's a metabolic superhighway where the breakdown products of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins converge for final oxidation.

Central Role in Aerobic Respiration:

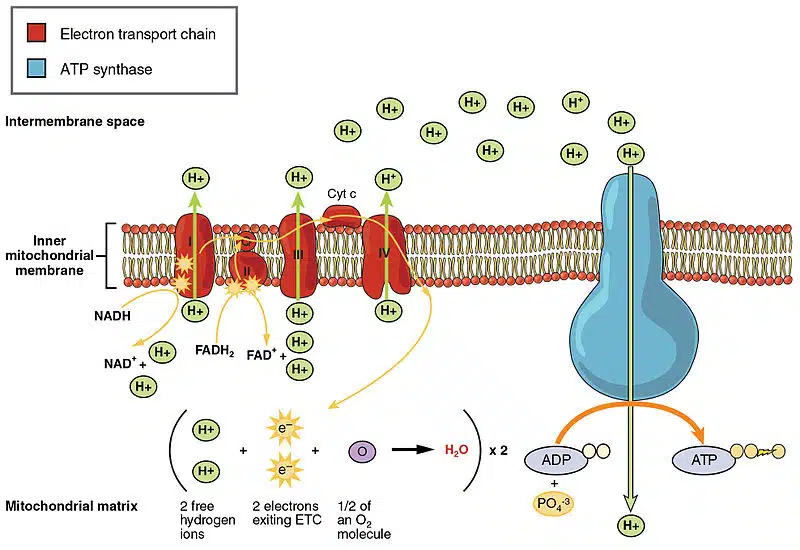

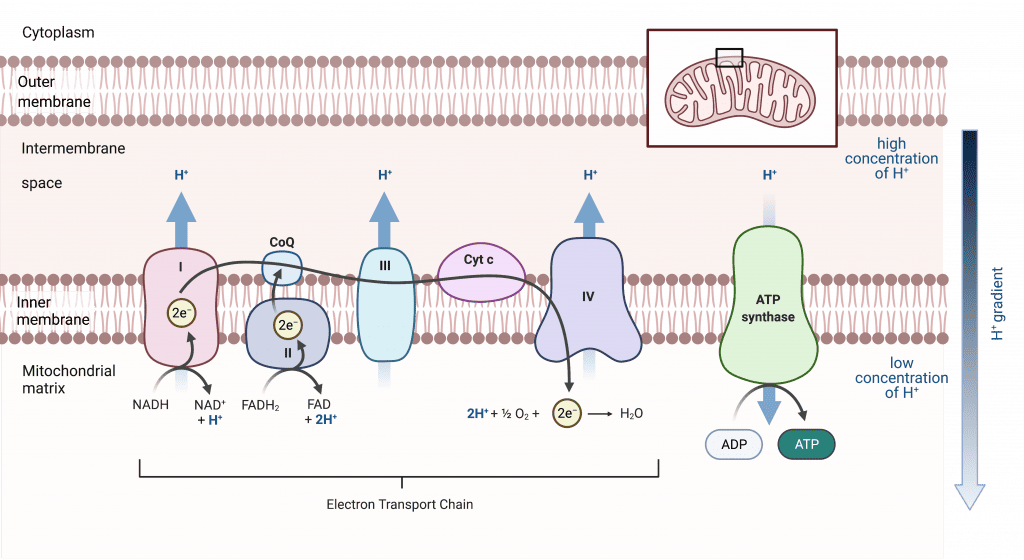

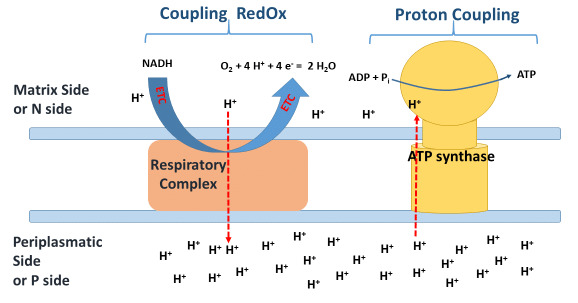

The TCA cycle is the second major stage of aerobic respiration. Unlike glycolysis, the TCA cycle requires oxygen indirectly to function, as its products (NADH and FADH₂) ultimately feed into the electron transport chain, which absolutely depends on oxygen. Without the ETC running, the NAD⁺ and FAD needed for the TCA cycle would not be regenerated, and the cycle would grind to a halt.

Main Function: Complete Oxidation of Acetyl-CoA:

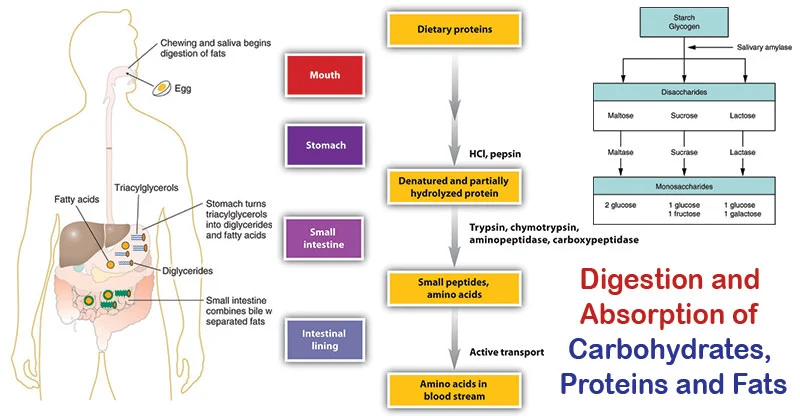

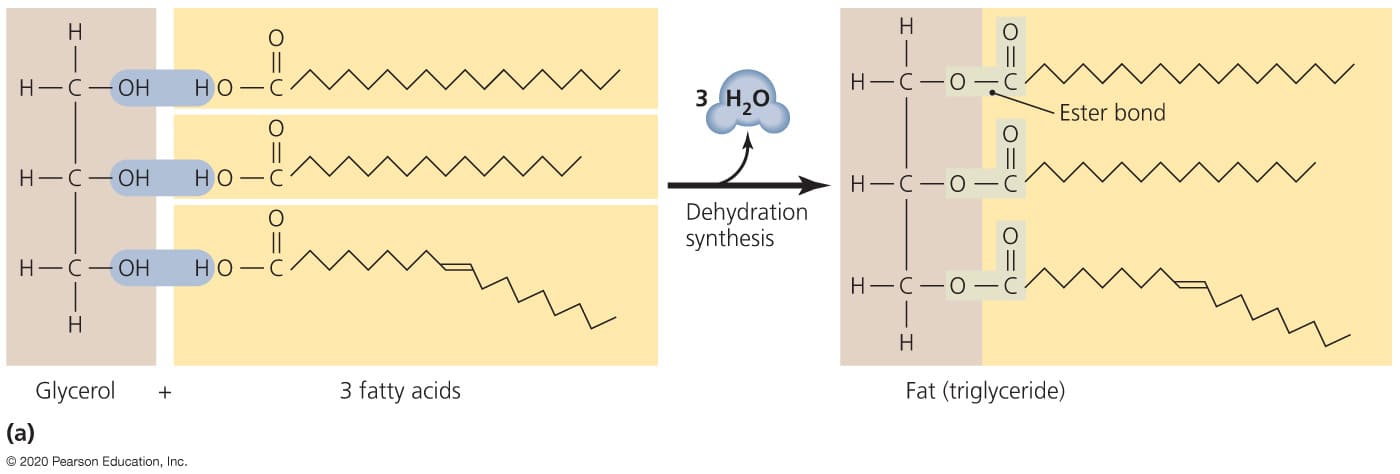

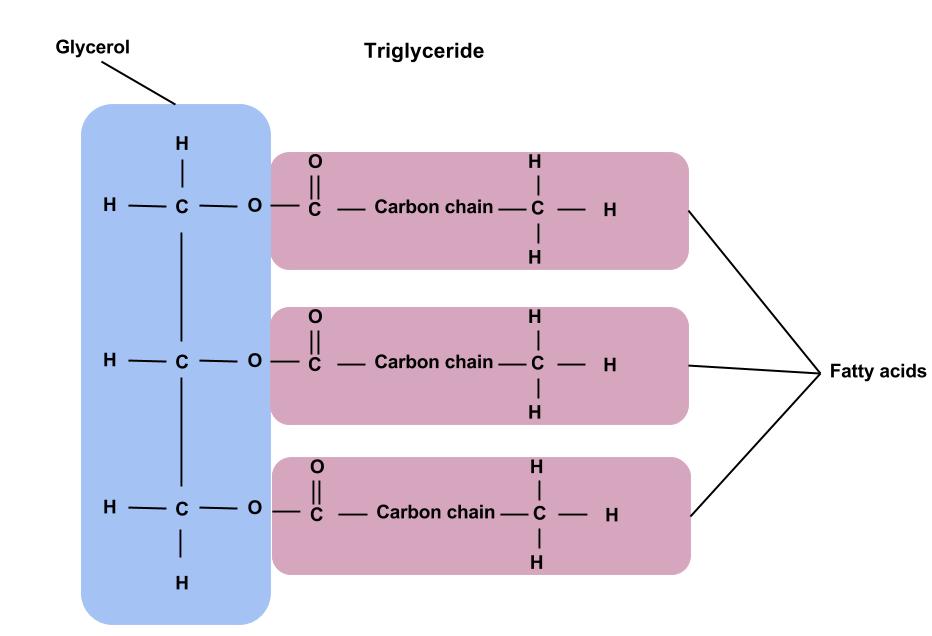

The primary catabolic function of the TCA cycle is the complete oxidation of acetyl-CoA to carbon dioxide (CO₂). This acetyl-CoA is primarily derived from:

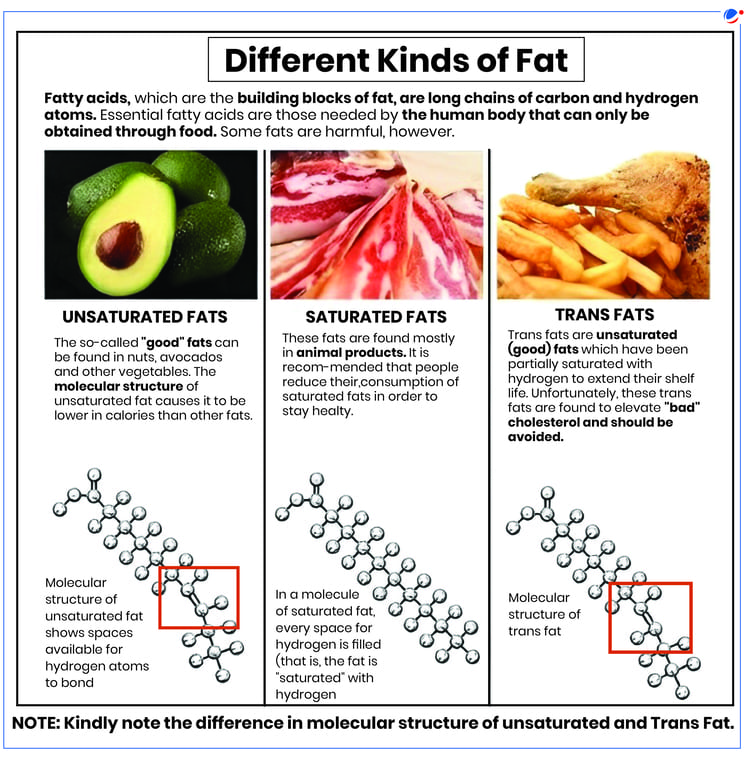

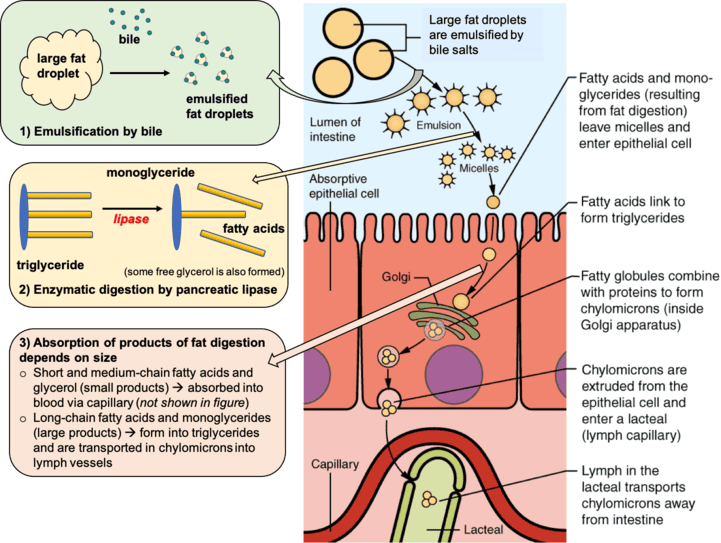

- Carbohydrates: Pyruvate (from glycolysis) is converted to acetyl-CoA.

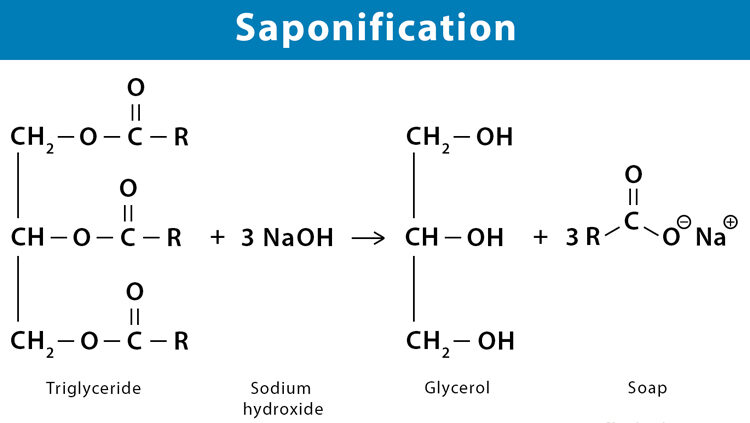

- Fats: Fatty acids are broken down into acetyl-CoA via beta-oxidation.

- Proteins: Certain amino acids are degraded into acetyl-CoA or other TCA cycle intermediates.

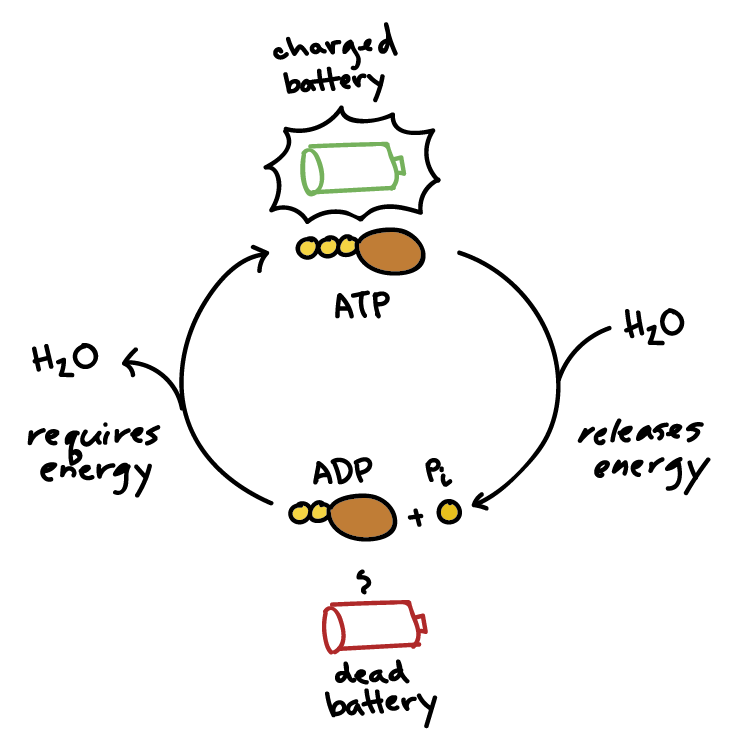

As acetyl-CoA is oxidized, the cycle captures the released energy in the form of high-energy electron carriers (NADH and FADH₂) and a small amount of GTP (which is interconvertible with ATP). These carriers are then channeled into the Electron Transport Chain (ETC) to drive the synthesis of the vast majority of cellular ATP.

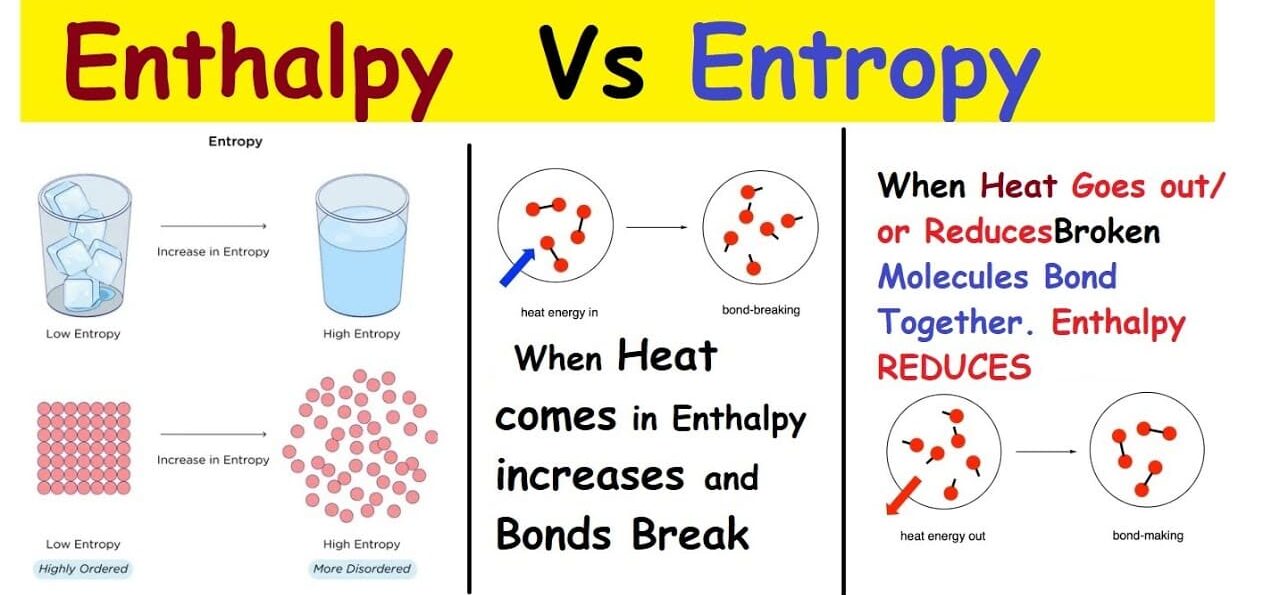

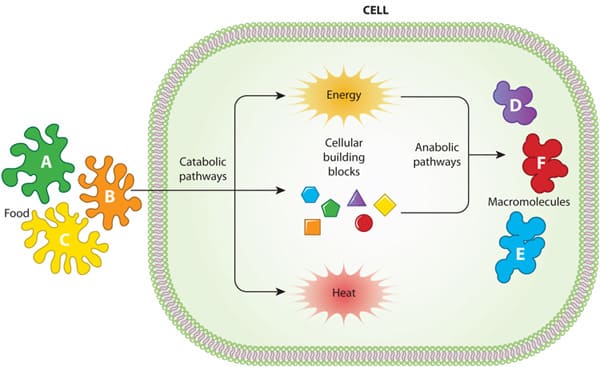

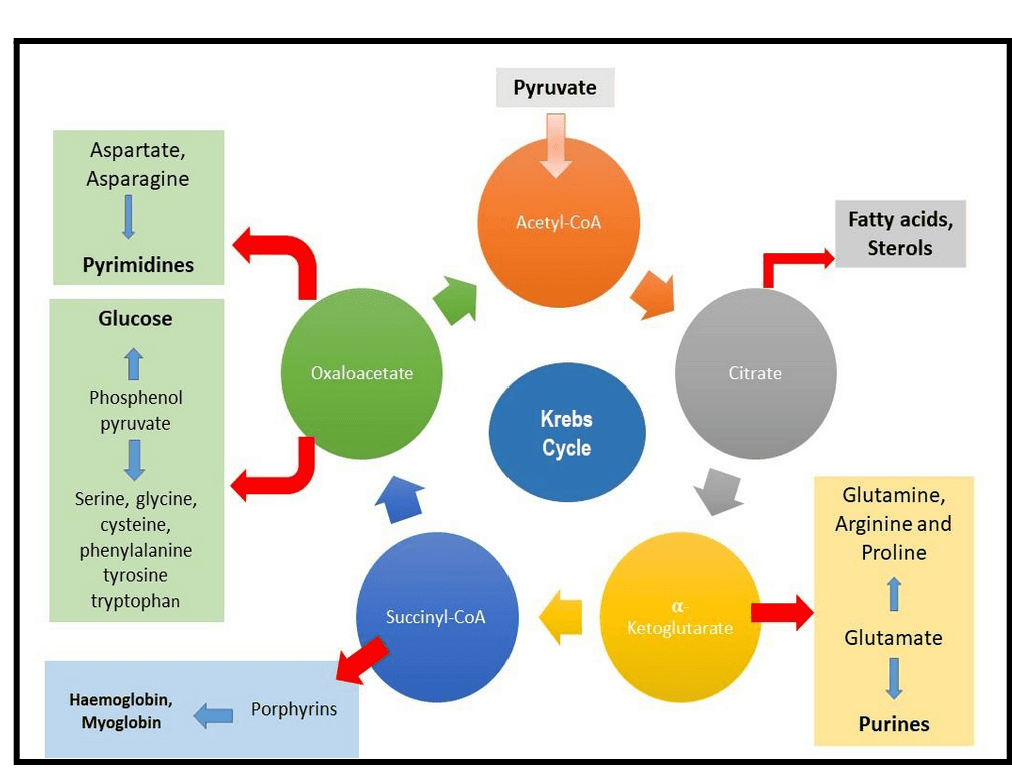

Amphibolic Nature (Both Catabolic and Anabolic Roles):

One of the most fascinating aspects of the TCA cycle is its amphibolic nature, meaning it serves both catabolic (breakdown) and anabolic (synthesis) roles.

- Catabolism: It catabolizes acetyl-CoA to CO₂, generating ATP, NADH, and FADH₂.

- Anabolism: Many of the intermediates are precursors for various biosynthetic pathways. For example:

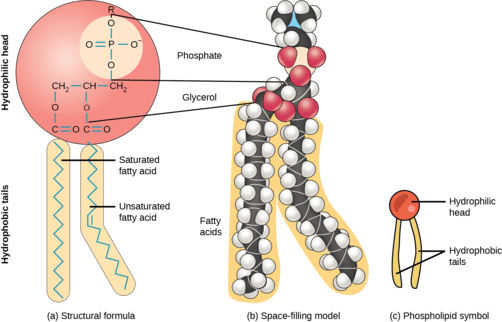

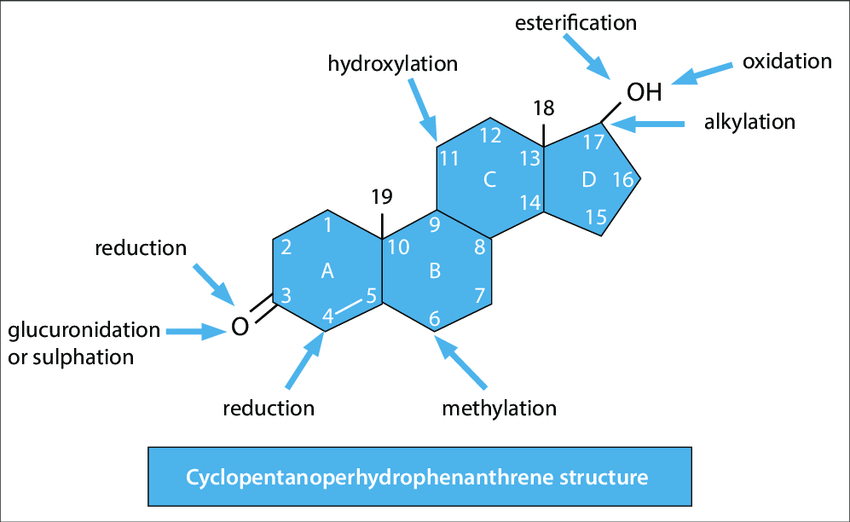

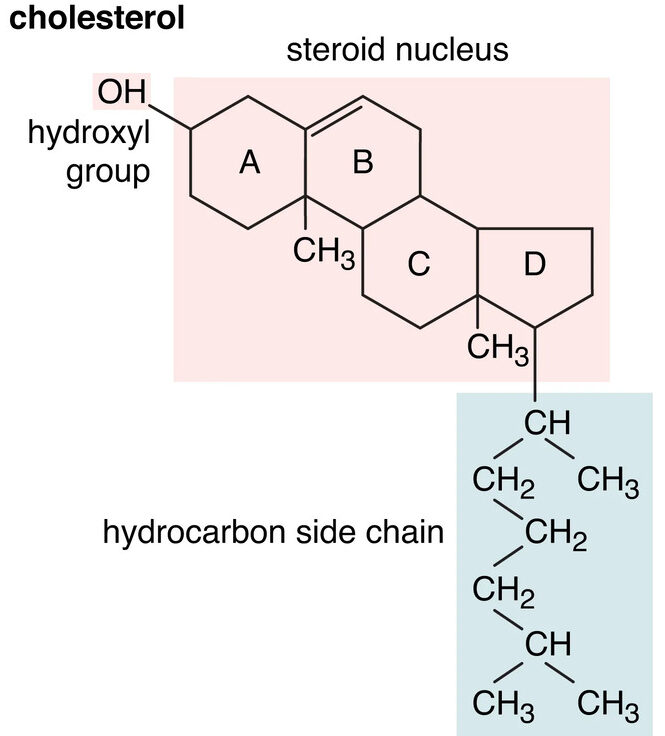

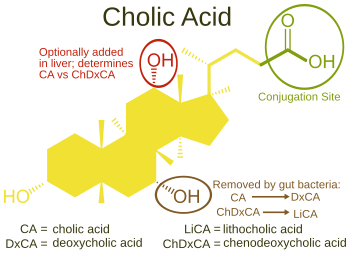

- Citrate can be used for fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis.

- α-Ketoglutarate is a precursor for several amino acids (e.g., glutamate).

- Succinyl-CoA is used in the synthesis of porphyrins (like heme).

- Oxaloacetate is a precursor for amino acids and glucose (via gluconeogenesis).

Because these intermediates are often "siphoned off" for synthesis, the cell has mechanisms (called anaplerotic reactions) to replenish them.

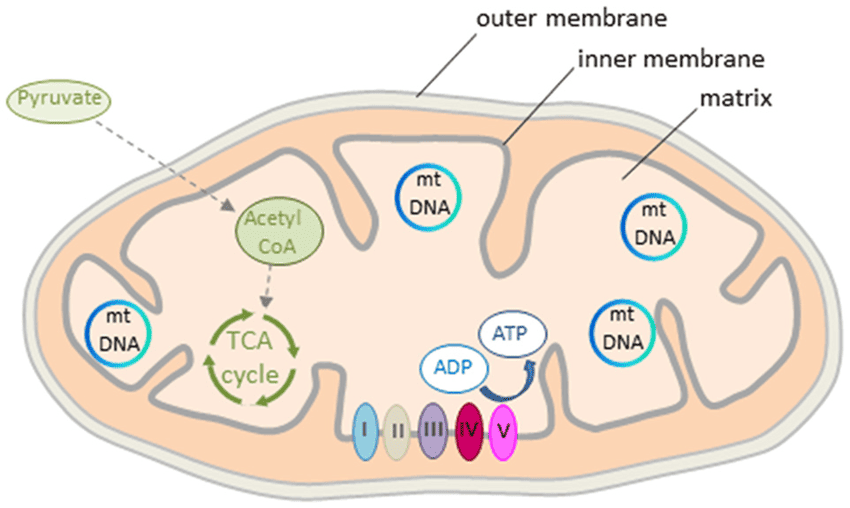

Location:

The location of the TCA cycle is critical to its function and regulation.

- Mitochondrial Matrix: In eukaryotic cells, the entire TCA cycle takes place within the mitochondrial matrix, the innermost compartment of the mitochondrion.

-

Why is this significant?

- Proximity to ETC: NADH and FADH₂ are produced directly where they are needed, ensuring efficient energy transfer to the ETC on the inner membrane.

- Isolation and Concentration: Confining the cycle within the matrix allows for the concentration of substrates and enzymes.

- Coupling with Oxidative Phosphorylation: This spatial arrangement is essential for the effective coupling of the TCA cycle with ATP production.

In prokaryotic cells, which lack mitochondria, the TCA cycle enzymes are found in the cytosol.

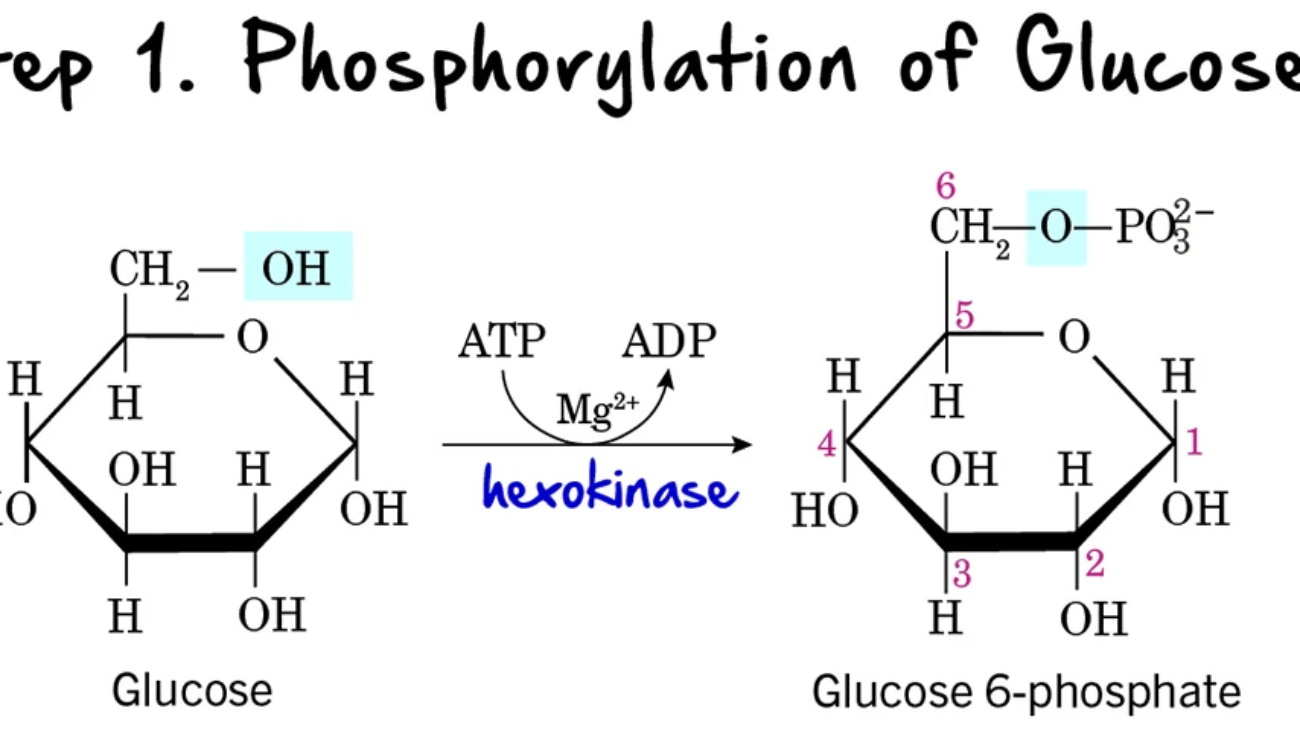

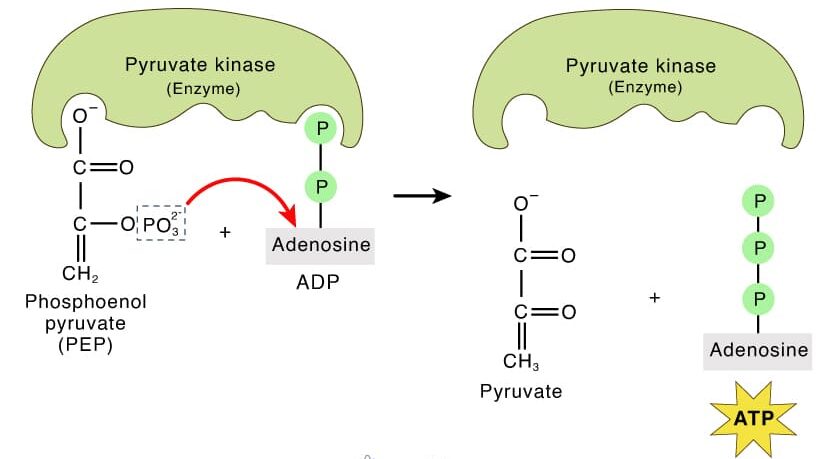

Entry Point: Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex (PDC)

The Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex (PDC) is a critical bridge between glycolysis and the TCA cycle. It's not part of the TCA cycle itself, but it's an absolutely essential prerequisite for aerobic glucose metabolism to proceed.

Irreversible Conversion of Pyruvate to Acetyl-CoA:

The PDC catalyzes an irreversible oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate to form acetyl-CoA. This reaction is a metabolic crossroads: once pyruvate is converted to acetyl-CoA, it cannot be converted back to glucose. The fate of glucose is committed to complete oxidation or fatty acid synthesis.

- Location: This reaction also takes place in the mitochondrial matrix. Pyruvate from glycolysis is transported into the matrix by a specific translocase protein.

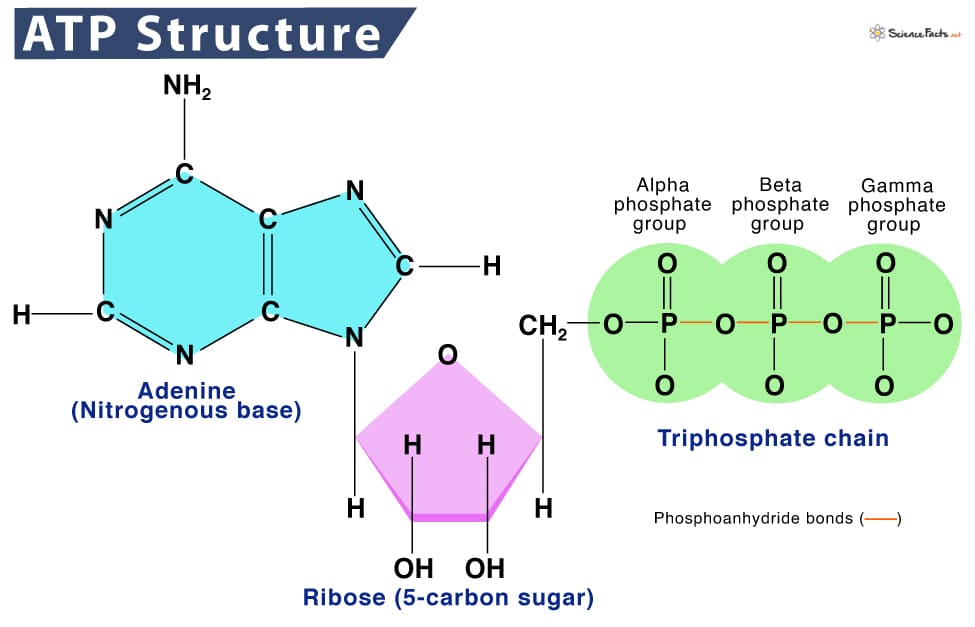

Overall Reaction and Coenzymes Involved:

The PDC is a complex of three distinct enzymes and five different coenzymes. The overall reaction is:

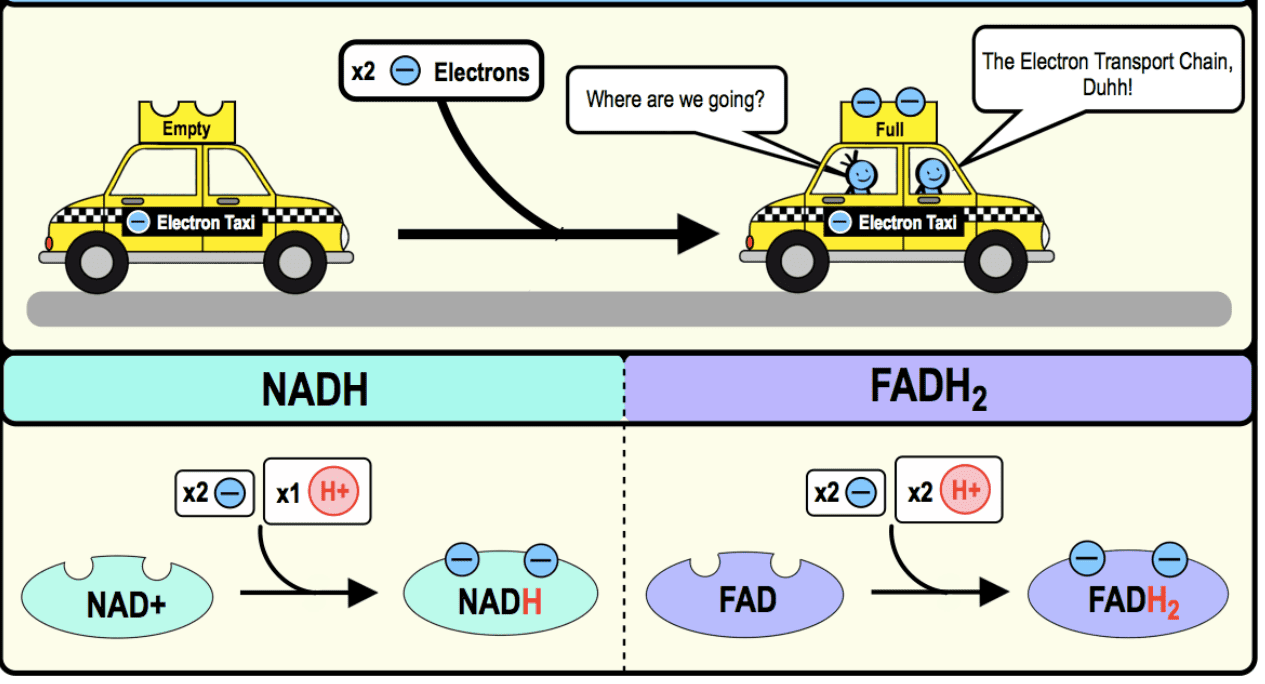

The Five Coenzymes (or Prosthetic Groups):

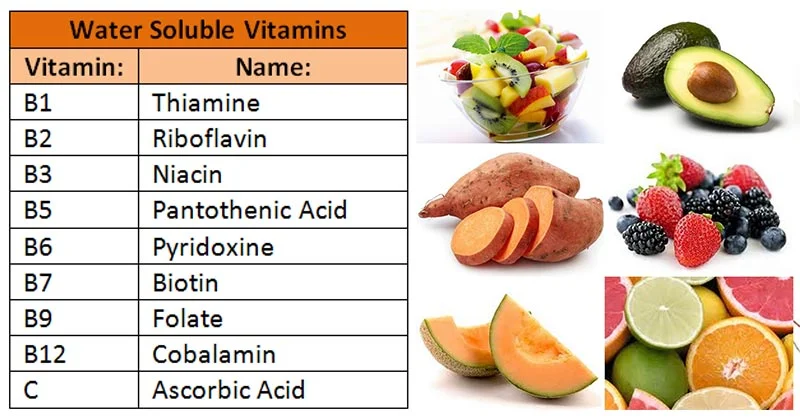

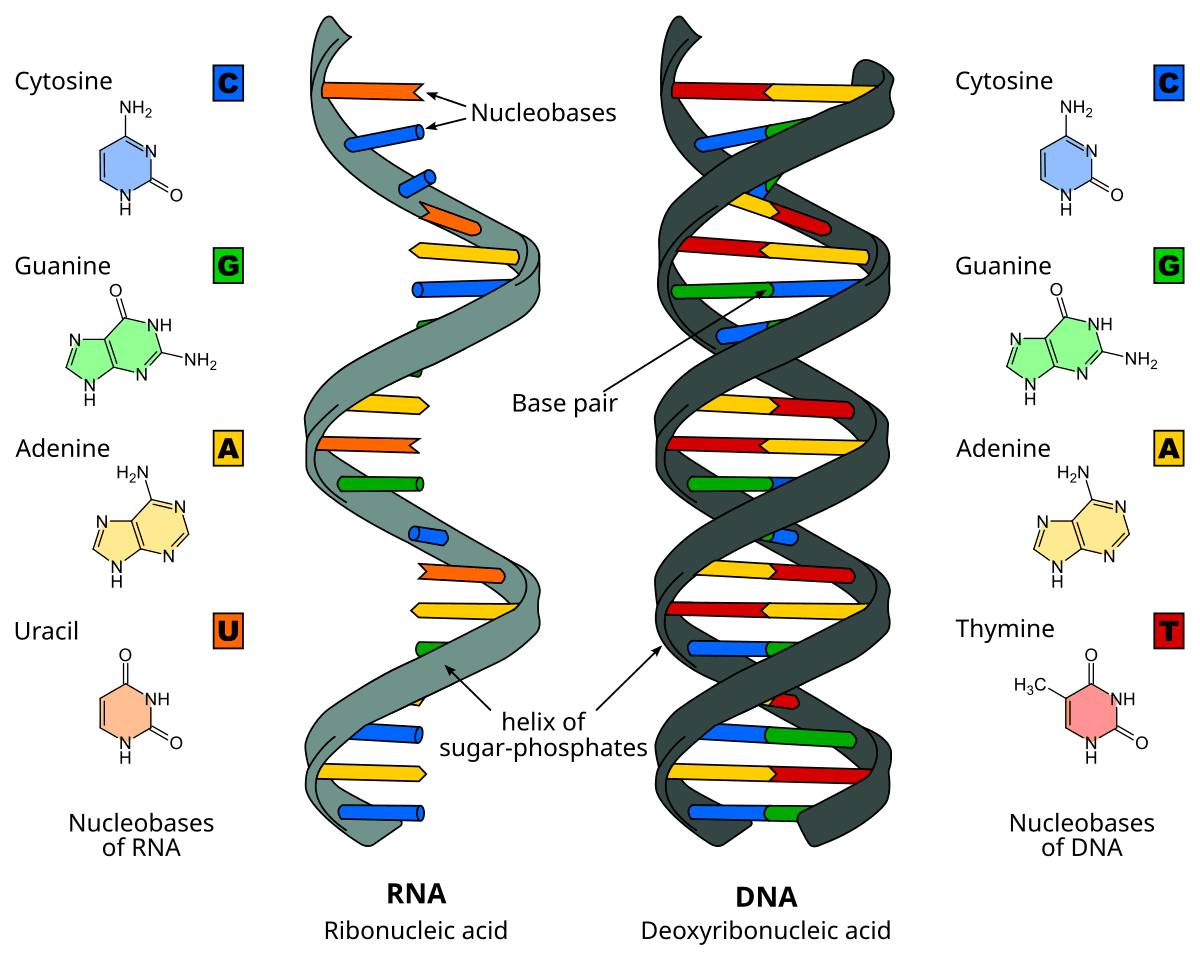

- Thiamine Pyrophosphate (TPP): From vitamin B1 (thiamine). Decarboxylates pyruvate.

- Lipoate (Lipoamide): Transfers the acetyl group to CoA.

- Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide (FAD): From vitamin B2 (riboflavin). Re-oxidizes the reduced lipoamide.

- Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD⁺): From vitamin B3 (niacin). Re-oxidizes FADH₂.

- Coenzyme A (CoA): From vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid). Accepts the acetyl group.

Regulation of the PDC:

Because this step is irreversible, the PDC is a crucial point of regulation.

-

Allosteric Regulation:

- Inhibitors (high energy signals): Acetyl-CoA, NADH, ATP.

- Activators (low energy signals): CoA, NAD⁺, AMP.

-

Covalent Modification (Phosphorylation/Dephosphorylation): This is the primary long-term regulatory mechanism.

- A PDC Kinase adds a phosphate group to INACTIVATE the PDC. The kinase is activated by high energy signals (ATP, NADH, Acetyl-CoA).

- A PDC Phosphatase removes the phosphate group to ACTIVATE the PDC. The phosphatase is activated by Ca²⁺ and insulin.

In summary, when the cell has plenty of energy, the PDC is turned off. When energy is needed, the PDC is activated.

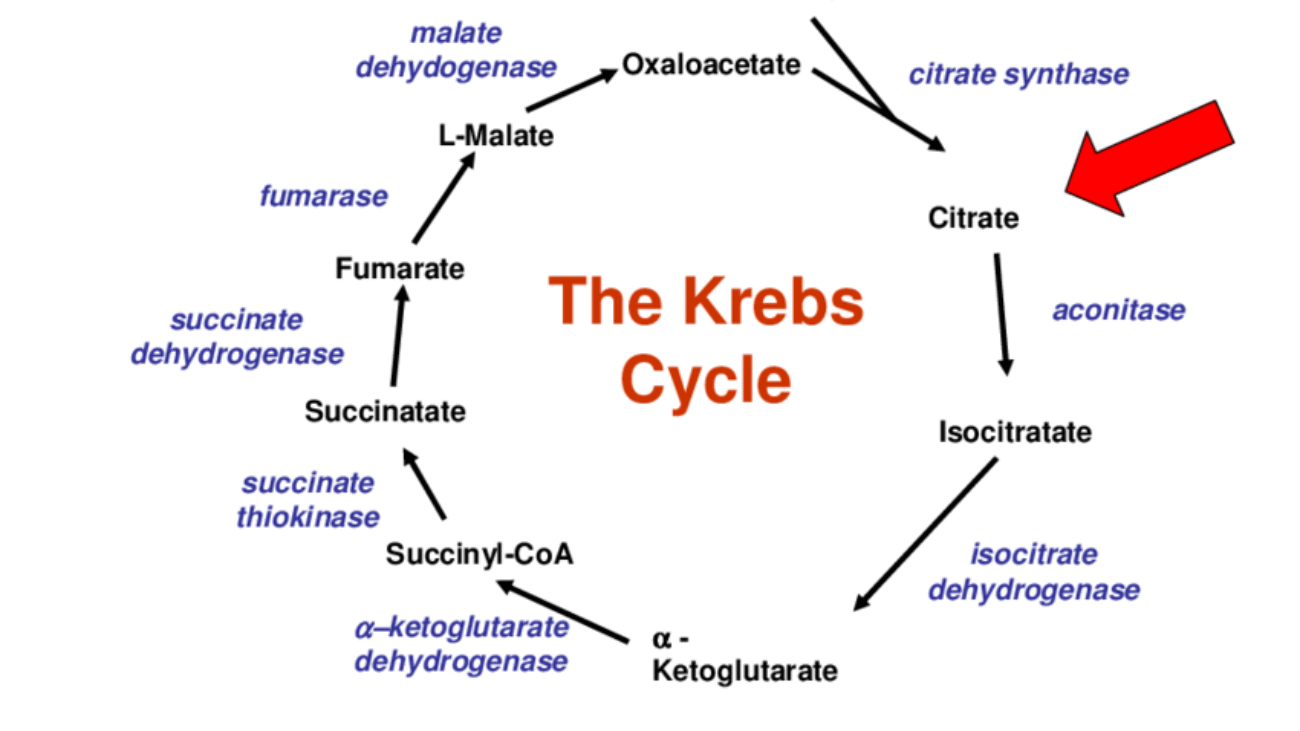

The Cycle Itself (Key Steps, Enzymes, and Products)

The cycle consists of eight enzymatic steps, leading to the complete oxidation of the two carbons from acetyl-CoA and the regeneration of oxaloacetate.

Overall Summary of One Turn of the Cycle:

- A four-carbon oxaloacetate condenses with a two-carbon acetyl unit (from acetyl-CoA) to yield a six-carbon citrate.

- Citrate is isomerized and then oxidatively decarboxylated to form five-carbon α-ketoglutarate, releasing one molecule of CO₂ and producing NADH.

- α-ketoglutarate is oxidatively decarboxylated to yield four-carbon succinyl-CoA, releasing another CO₂ and producing NADH.

- Succinyl-CoA is converted to succinate, generating one GTP (or ATP).

- Oxaloacetate is regenerated from succinate through a series of steps involving fumarate and malate, producing one FADH₂ and one NADH.

In total, two carbon atoms (from acetyl-CoA) enter the cycle, and two carbon atoms leave as CO₂. Energy is captured as 3 NADH, 1 FADH₂, and 1 GTP (ATP).

The Reactions of the Citric Acid Cycle

Now that Acetyl-CoA has been generated in the mitochondrial matrix, it enters the eight-step cyclical pathway. Each turn of the cycle processes one molecule of Acetyl-CoA, systematically oxidizing its two carbons to CO₂ while capturing high-energy electrons in the form of NADH and FADH₂. Let's examine each step.

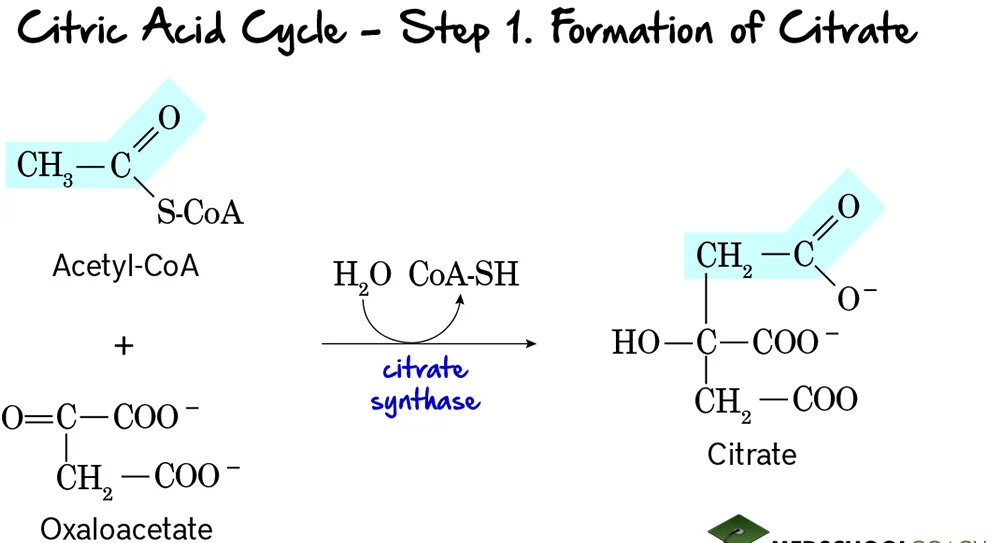

Step 1: Formation of Citrate

This is the entry point for the 2-carbon acetyl group into the citric acid cycle. It involves the condensation of a 2-carbon unit with a 4-carbon molecule to form a 6-carbon molecule.

Reaction:

Acetyl-CoA (a 2-carbon molecule) condenses with Oxaloacetate (a 4-carbon molecule). This reaction, accompanied by the hydrolysis of the thioester bond in Acetyl-CoA, forms Citrate, a 6-carbon tricarboxylic acid.

Key Features of Step 1:

- Enzyme: The reaction is catalyzed by Citrate Synthase. This is a crucial regulatory enzyme of the TCA cycle.

- Reactants: Acetyl-CoA and Oxaloacetate.

- Product: Citrate and Coenzyme A (CoA-SH).

- Type of Reaction: This is a condensation reaction.

- Irreversibility: The reaction is highly exergonic and essentially irreversible under cellular conditions, making it a key control point.

- Regulation: Citrate synthase is allosterically inhibited by high levels of ATP, NADH, succinyl-CoA, and its own product, citrate. These are all signals that the cell has a high energy charge and an abundance of metabolic intermediates.

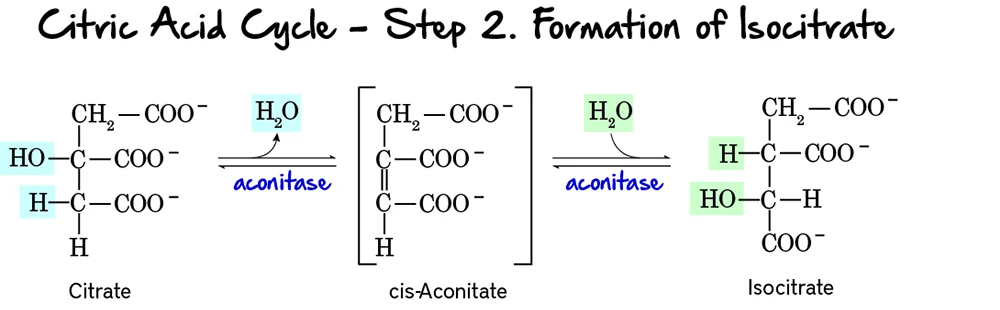

Step 2: Formation of Isocitrate

This step involves the isomerization of citrate to isocitrate. This rearrangement is crucial because the hydroxyl group of isocitrate is positioned to be oxidized in the next step.

Reaction:

Citrate, a tertiary alcohol, is isomerized to Isocitrate, a secondary alcohol. The reaction occurs in two substeps: first, a molecule of water is removed to form cis-Aconitate, and then water is re-added in a different position.

Key Features of Step 2:

- Enzyme: The enzyme catalyzing this reversible reaction is Aconitase. It contains an iron-sulfur cluster essential for its activity.

- Reactant: Citrate.

- Product: Isocitrate.

- Type of Reaction: An isomerization, specifically an intramolecular rearrangement involving dehydration and rehydration.

- Reversibility: The reaction is reversible, but the subsequent steps quickly consume isocitrate, pulling the reaction forward.

Purpose of this Step:

- Preparation for Oxidation: Citrate, being a tertiary alcohol, is not readily oxidizable. The isomerization to isocitrate, a secondary alcohol, positions the hydroxyl group at a carbon that can be easily oxidized in the next step.

- Stereospecificity: Aconitase catalyzes a stereospecific conversion, meaning it produces a specific isomer of isocitrate.

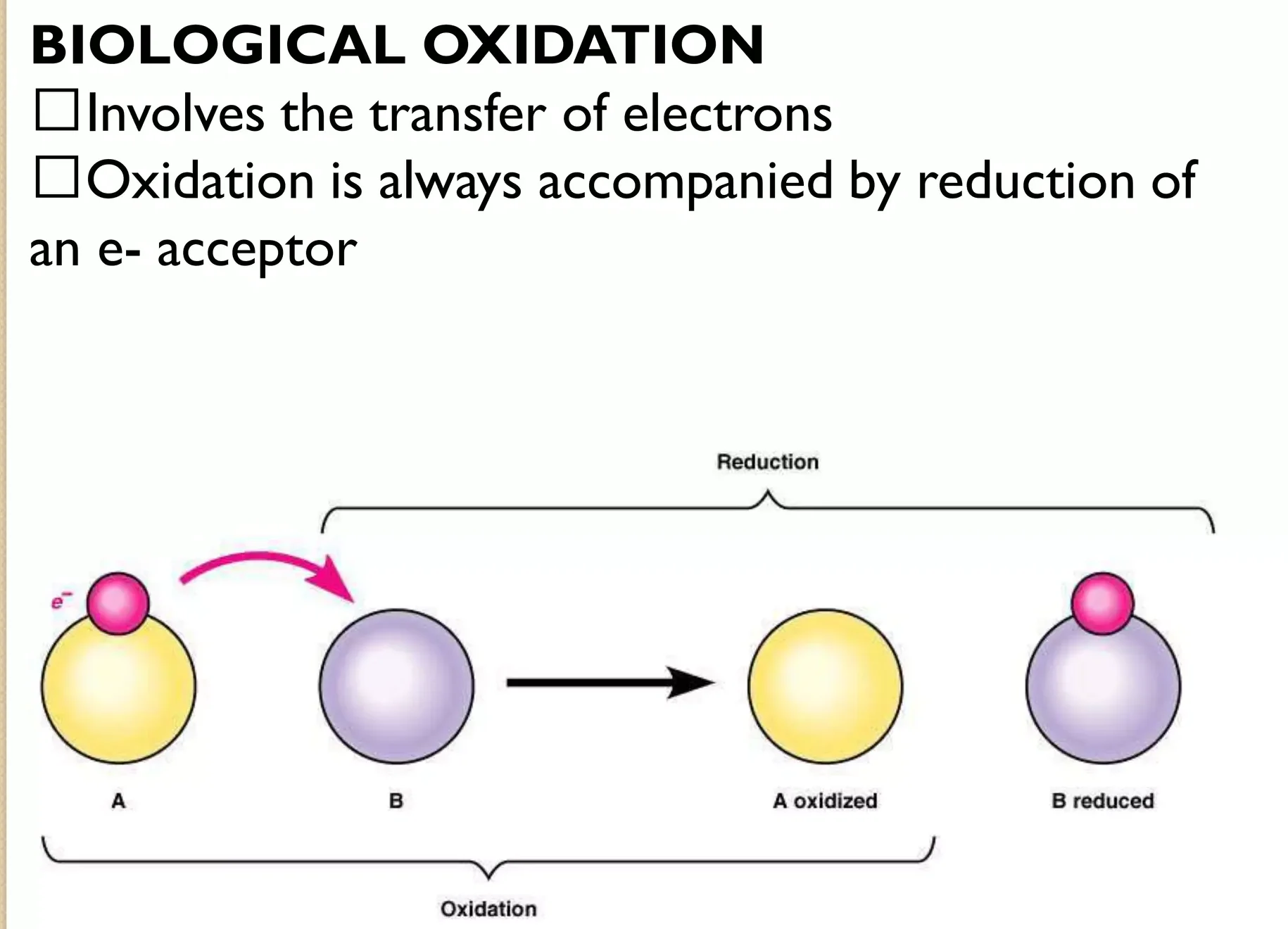

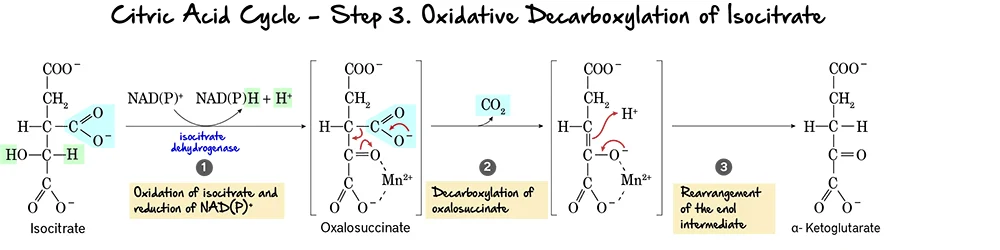

Step 3: Oxidative Decarboxylation of Isocitrate

This is the first oxidative step in the citric acid cycle, where the first molecule of carbon dioxide is released and the first NADH is produced.

Reaction:

Isocitrate undergoes an oxidative decarboxylation reaction. This involves two main parts:

- Oxidation: The hydroxyl group on isocitrate is oxidized to a keto group, reducing NAD⁺ to NADH.

- Decarboxylation: The beta-keto acid intermediate, Oxalosuccinate, immediately loses a molecule of carbon dioxide (CO₂), forming alpha-Ketoglutarate.

Key Features of Step 3:

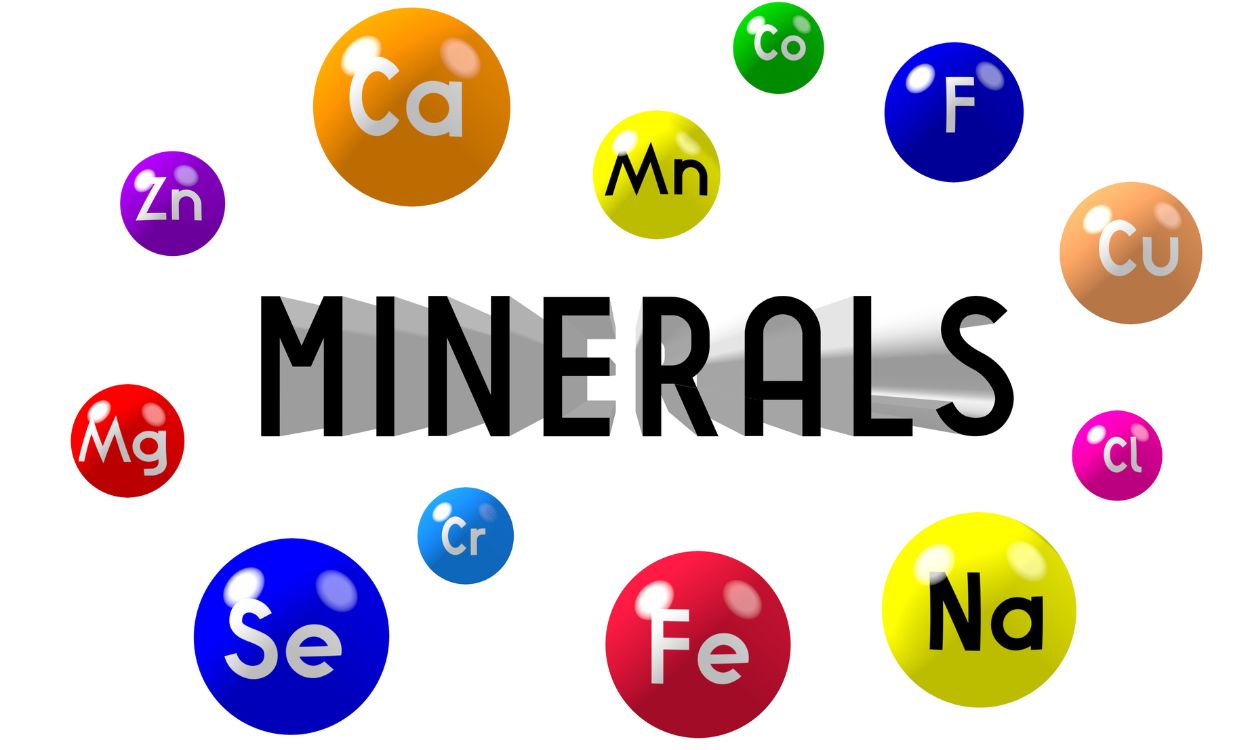

- Enzyme: The reaction is catalyzed by Isocitrate Dehydrogenase. This enzyme requires

Mn²⁺as a cofactor. - Reactant: Isocitrate.

- Product: alpha-Ketoglutarate and CO₂.

- Electron Carriers Reduced:

NAD⁺is reduced toNADH. - ATP Change: 0 ATP directly produced.

Purpose of this Step:

- CO₂ Release: This is the first of two carbon atoms released as CO₂ from the original acetyl unit.

- NADH Production: The generation of NADH is vital for ATP production via oxidative phosphorylation.

- Regulation: Isocitrate Dehydrogenase is a crucial regulatory enzyme. It is allosterically activated by ADP (indicating low energy) and inhibited by ATP and NADH (indicating high energy).

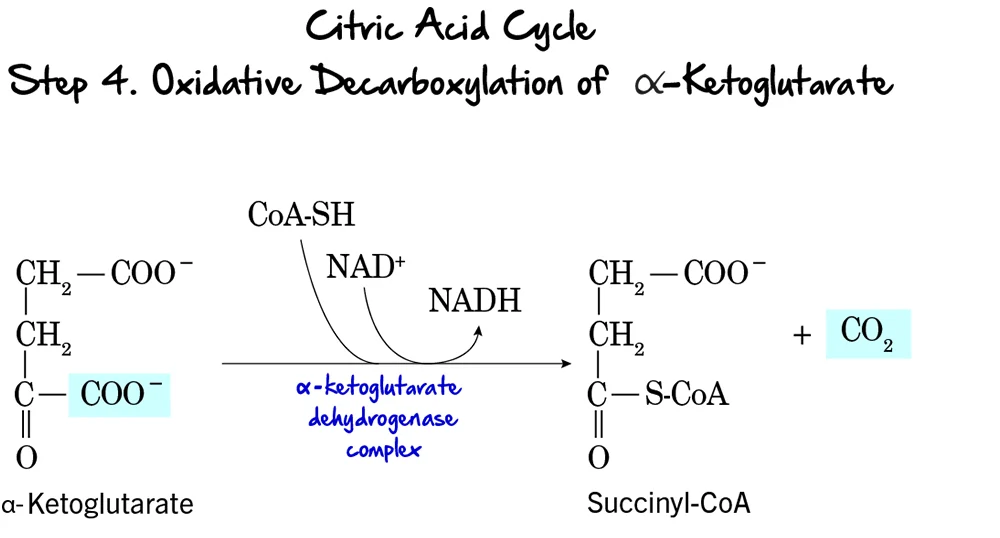

Step 4: Oxidative Decarboxylation of alpha-Ketoglutarate

This is the second and final oxidative decarboxylation step in the citric acid cycle. It is remarkably similar in mechanism to the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex reaction.

Reaction:

alpha-Ketoglutarate undergoes oxidative decarboxylation to form Succinyl-CoA. This complex reaction involves the release of another molecule of CO₂, the reduction of NAD⁺ to NADH, and the incorporation of Coenzyme A.

Key Features of Step 4:

- Enzyme: This reaction is catalyzed by the alpha-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase Complex. This is a multi-enzyme complex requiring several coenzymes (Thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP), Lipoamide, FAD, NAD⁺, and CoA-SH).

- Reactant: alpha-Ketoglutarate.

- Product: Succinyl-CoA, CO₂, and NADH.

- Electron Carriers Reduced:

NAD⁺is reduced toNADH. - ATP Change: 0 ATP directly produced.

Purpose of this Step:

- CO₂ Release: This is the second and last carbon atom released as CO₂. At this point, both carbons from the initial acetyl-CoA have been fully oxidized.

- NADH Production: This NADH contributes significantly to ATP production.

- Formation of a High-Energy Thioester: The formation of succinyl-CoA, with its high-energy thioester bond, primes the molecule for the substrate-level phosphorylation step that follows.

- Regulation: The alpha-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase Complex is another regulatory point. It is inhibited by its products, Succinyl-CoA and NADH, and also by high ATP levels.

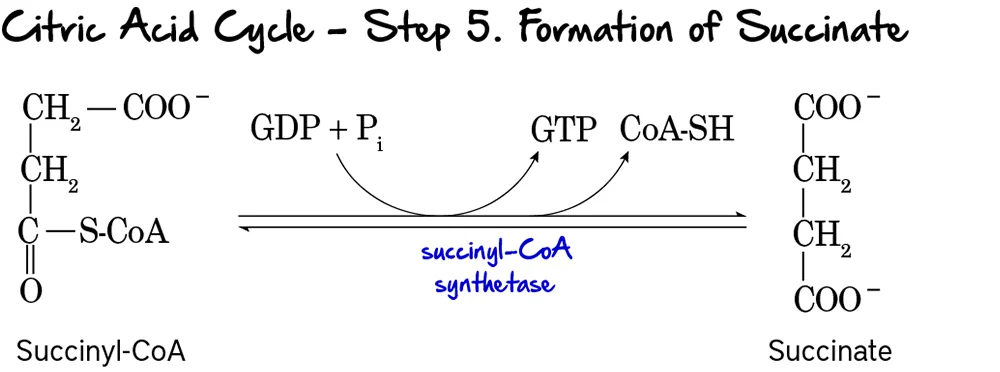

Step 5: Formation of Succinate (Substrate-Level Phosphorylation)

This is the only step in the Citric Acid Cycle that directly generates a high-energy phosphate compound (GTP or ATP) through substrate-level phosphorylation.

Reaction:

The high-energy thioester bond of Succinyl-CoA is hydrolyzed. The energy released drives the phosphorylation of GDP to GTP. Coenzyme A is released, and Succinate is formed.

Key Features of Step 5:

- Enzyme: Succinyl-CoA Synthetase (also known as Succinate Thiokinase).

- Reactant: Succinyl-CoA.

- Products: Succinate, CoA-SH, and GTP (or ATP).

- Energy Production: 1 GTP is produced per turn. GTP can be readily converted to ATP (

GTP + ADP ↔ GDP + ATP).

Purpose of this Step:

- ATP/GTP Generation: This provides a direct energy yield for the cell.

- Regeneration of Succinate: Succinate is now available for further processing.

- Removal of CoA: The release of free CoA is important for other enzyme complexes to function.

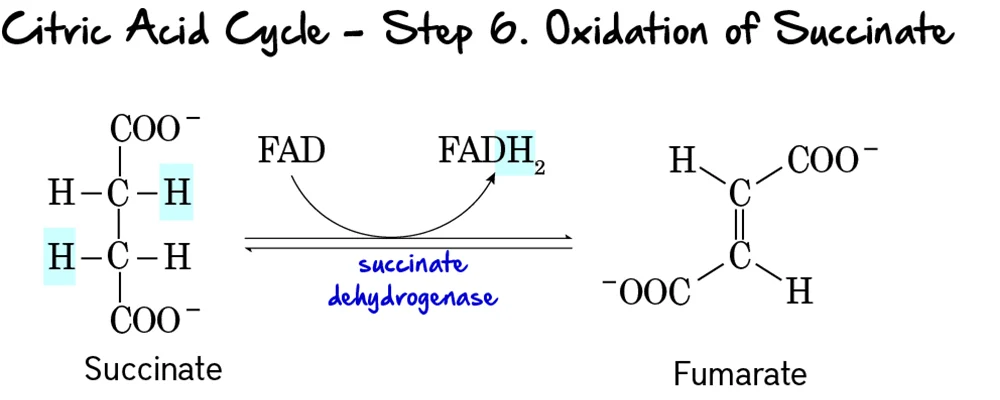

Step 6: Oxidation of Succinate

This is the second oxidative step in the cycle, where electrons are transferred to FAD, producing FADH₂.

Reaction:

Succinate is oxidized to Fumarate through the removal of two hydrogen atoms. These hydrogens are accepted by FAD, which is reduced to FADH₂. This reaction forms a double bond in fumarate.

Key Features of Step 6:

- Enzyme: Succinate Dehydrogenase. This enzyme is unique as it is an integral protein of the inner mitochondrial membrane and is directly part of the electron transport chain (Complex II).

- Reactant: Succinate.

- Products: Fumarate and FADH₂.

- Electron Carriers Reduced:

FADis reduced toFADH₂. - ATP Change: 0 ATP directly produced.

Purpose of this Step:

- FADH₂ Production: FADH₂ is another high-energy electron carrier that will donate its electrons to the ETC. It yields fewer ATP than NADH because it enters the ETC at a lower energy level.

- Connection to Electron Transport Chain: Being part of Complex II directly links the Citric Acid Cycle to the ETC, facilitating efficient electron transfer.

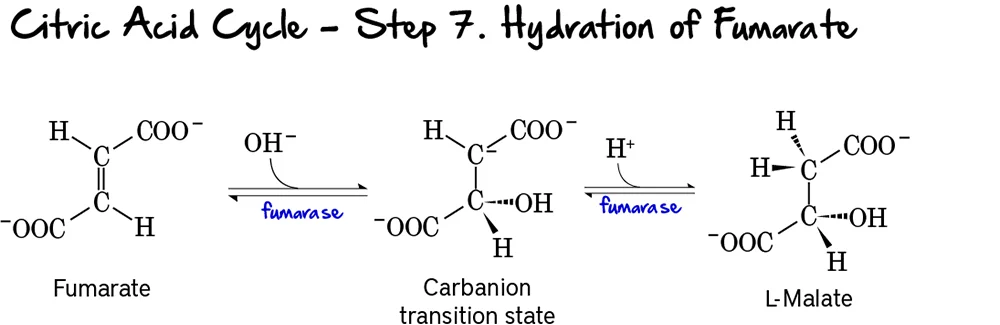

Step 7: Hydration of Fumarate

This step involves the stereospecific addition of water across the double bond of fumarate, forming L-malate.

Reaction:

Fumarate undergoes a hydration reaction, where a molecule of water is added across its double bond. This reaction forms L-Malate.

Key Features of Step 7:

- Enzyme: Fumarase (also known as Fumarate Hydratase).

- Reactant: Fumarate.

- Product: L-Malate.

- Type of Reaction: This is a hydration reaction.

- Stereospecificity: Fumarase is highly stereospecific, forming specifically L-malate (not D-malate).

- Reversibility: This reaction is reversible.

Purpose of this Step:

- Preparation for Oxidation: The addition of water creates a hydroxyl group on L-malate, which is necessary for the subsequent oxidation step.

- Regeneration of Oxaloacetate: This step is crucial for setting up the regeneration of oxaloacetate.

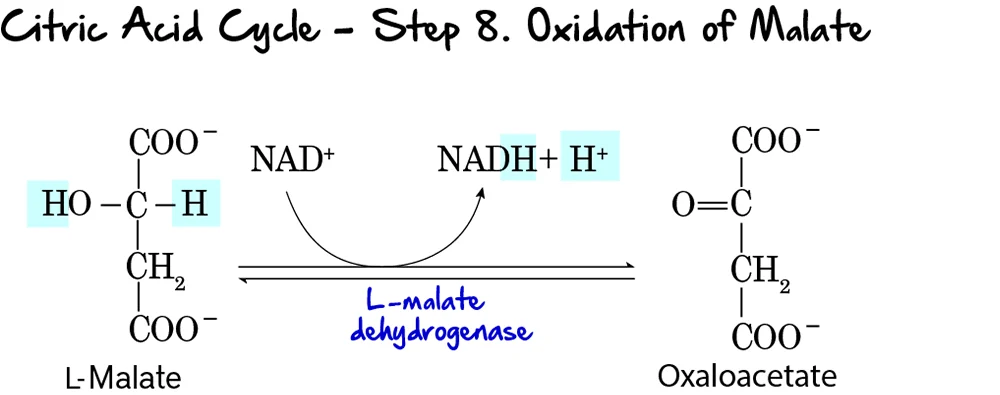

Step 8: Oxidation of Malate

This is the final step of the Citric Acid Cycle, regenerating oxaloacetate and producing the last NADH of the cycle.

Reaction:

L-Malate is oxidized to Oxaloacetate. During this oxidation, NAD⁺ is reduced to NADH and H⁺. This completes the regeneration of oxaloacetate, which is now ready to condense with another molecule of acetyl-CoA.

Key Features of Step 8:

- Enzyme: L-Malate Dehydrogenase.

- Reactant: L-Malate.

- Products: Oxaloacetate and NADH + H⁺.

- Electron Carriers Reduced:

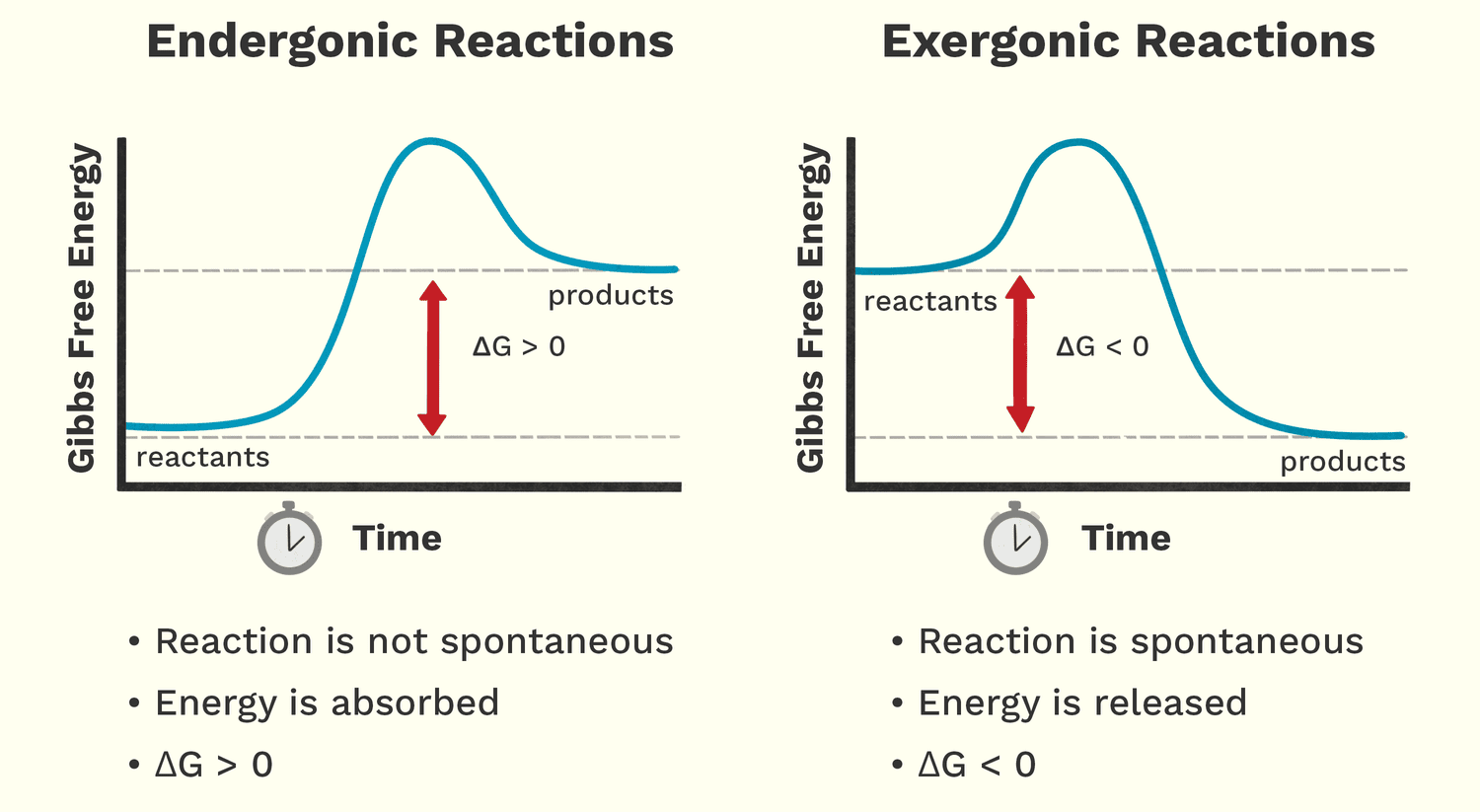

NAD⁺is reduced toNADH. - Reversibility: This reaction has a highly positive standard free energy change (

ΔG°'), making it thermodynamically unfavorable. However, in the cell, the rapid consumption of oxaloacetate by citrate synthase (Step 1) pulls this reaction forward.

Purpose of this Step:

- Regeneration of Oxaloacetate: This is the most critical function, ensuring the cycle can continue to operate.

- NADH Production: This produces the third and final molecule of NADH generated directly within the cycle (per acetyl-CoA).

- Completion of the Cycle: With the regeneration of oxaloacetate, the cycle is complete.

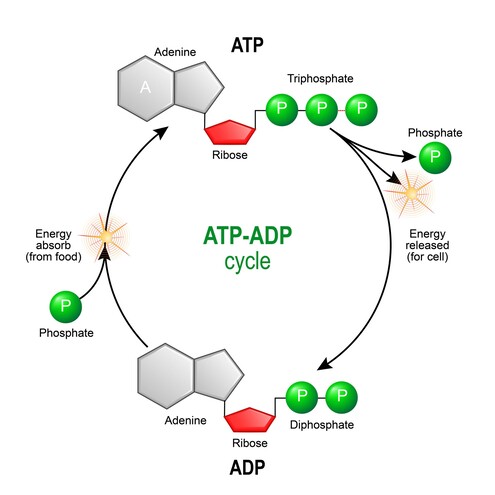

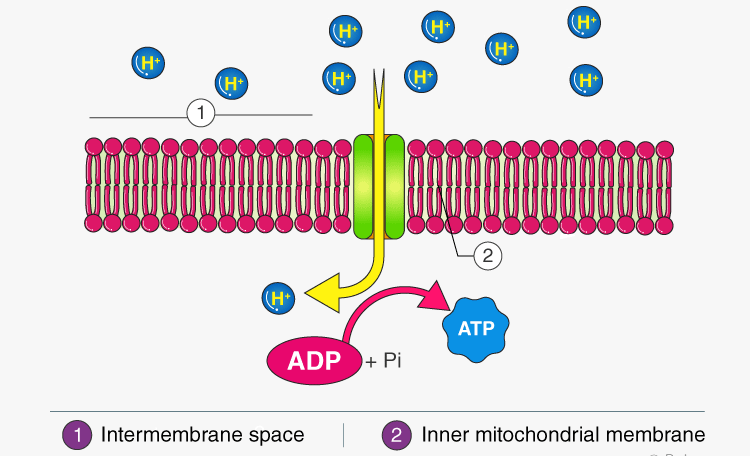

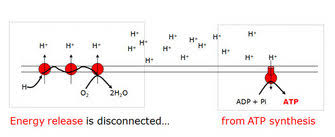

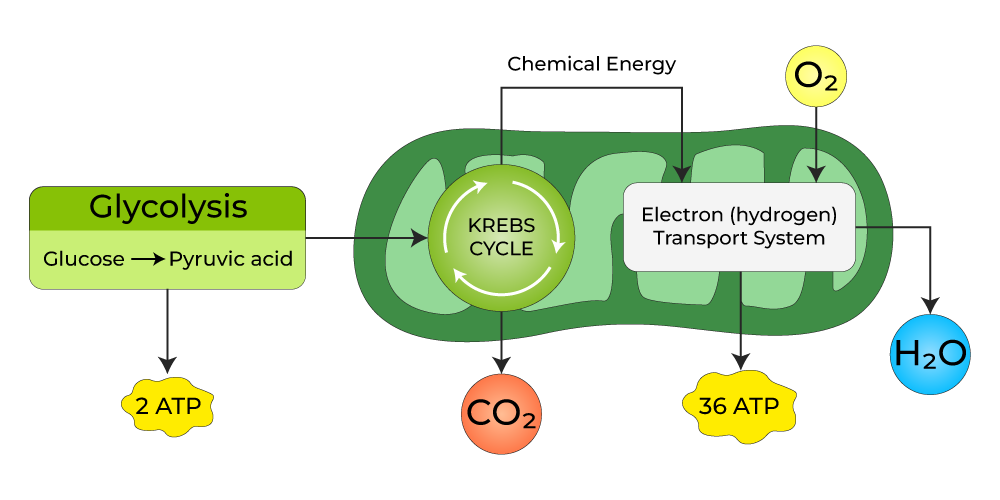

Energy Yield

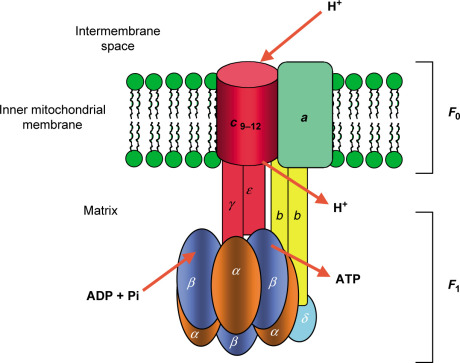

The primary purpose of breaking down glucose is to generate ATP. While glycolysis and the TCA cycle directly produce a small amount, the vast majority of ATP is generated indirectly through oxidative phosphorylation, utilizing the NADH and FADH₂ produced.

Let's summarize the yield from one molecule of glucose through the complete process.

1. Glycolysis (Cytosol):

- Net ATP: 2 ATP (via substrate-level phosphorylation)

- NADH: 2 NADH

2. Pyruvate Oxidation (PDC - Mitochondrial Matrix):

Since one glucose yields two pyruvate molecules, this reaction occurs twice.

- CO₂: 2 CO₂ (1 per pyruvate)

- NADH: 2 NADH (1 per pyruvate)

3. TCA Cycle (Mitochondrial Matrix):

Since two acetyl-CoA molecules enter the cycle (from one glucose), the cycle runs twice.

Per turn of the cycle (i.e., per Acetyl-CoA):

- GTP/ATP: 1 GTP (equivalent to 1 ATP)

- NADH: 3 NADH

- FADH₂: 1 FADH₂

- CO₂: 2 CO₂

For two turns of the cycle (i.e., per Glucose):

- GTP/ATP: 2 GTP (equivalent to 2 ATP)

- NADH: 6 NADH

- FADH₂: 2 FADH₂

- CO₂: 4 CO₂

4. Total Yield (Direct and Indirect) per Glucose Molecule:

Let's consolidate the reduced coenzymes and directly produced ATP:

| Stage | ATP/GTP (Direct) | NADH | FADH₂ | CO₂ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Pyruvate Oxidation (x2) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| TCA Cycle (x2) | 2 | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| TOTAL (before ETC) | 4 | 10 | 2 | 6 |

5. Contribution to ATP Generation via Oxidative Phosphorylation:

Now, we account for the ATP generated from NADH and FADH₂ through the ETC. Standard estimations are:

- 1 NADH ≈ 2.5 ATP

- 1 FADH₂ ≈ 1.5 ATP

Using these conversion factors:

- ATP from 10 NADH: 10 NADH * 2.5 ATP/NADH = 25 ATP

- ATP from 2 FADH₂: 2 FADH₂ * 1.5 ATP/FADH₂ = 3 ATP

6. Overall Theoretical Maximum ATP Yield from One Glucose Molecule:

| Source | ATP Yield |

|---|---|

| Direct ATP/GTP | 4 |

| From 10 NADH (via ETC) | 25 |

| From 2 FADH₂ (via ETC) | 3 |

| TOTAL ATP | ~32 ATP |

Key Takeaways:

- Most ATP is made indirectly: The vast majority is produced through oxidative phosphorylation, driven by

NADHandFADH₂. - Complete Oxidation: The 6 carbons from glucose are completely oxidized to 6 molecules of

CO₂. - Efficiency: The TCA cycle is incredibly efficient at extracting energy from acetyl-CoA and channeling it into electron carriers for maximal ATP production.

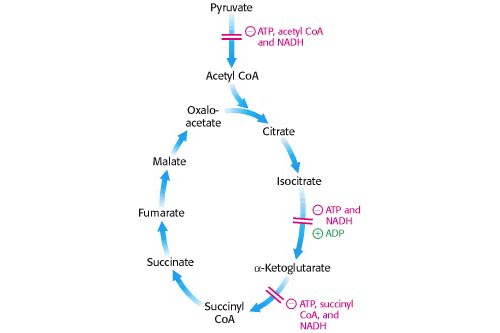

Regulation of the TCA Cycle

The TCA cycle is meticulously regulated to ensure that energy production aligns with the cell's demand. Regulation primarily occurs at the irreversible steps through allosteric control. The cycle slows down when the cell has ample ATP and speeds up when energy is needed.

Key Control Points within the Cycle:

Three main enzymes catalyze irreversible reactions and are thus primary targets for regulation:

- Citrate Synthase (Step 1)

- Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (Step 3) - Often considered a major rate-limiting step.

- α-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase Complex (Step 4)

Mechanisms of Regulation:

The TCA cycle's activity is finely tuned by several mechanisms, with allosteric modulation being the primary mode of control.

Allosteric Modulators:

This is the primary mode of regulation. Various molecules signal the cell's energy status, directly binding to and altering the activity of the regulatory enzymes.

Citrate Synthase (Step 1)

Activated by:

- ADP (low energy)

Inhibited by:

- ATP, NADH, Succinyl-CoA, Citrate (all are high energy signals or products).

Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (Step 3)

Activated by:

- ADP (low energy).

- Ca²⁺ (signals muscle contraction / energy demand).

Inhibited by:

- ATP, NADH (high energy signals).

α-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase (Step 4)

Activated by:

- Ca²⁺ (signals energy demand).

Inhibited by:

- Succinyl-CoA, NADH (product inhibition).

- ATP (high energy signal).

Other Regulatory Mechanisms:

- Covalent Modification: This is not a common regulatory mechanism for the core TCA cycle enzymes in eukaryotes. However, it is the primary control method for the Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex (PDC), which controls the entry of acetyl-CoA into the cycle.

- Supply of Acetyl-CoA: The activity of the PDC is a critical determinant of the flux into the TCA cycle, effectively controlling the primary fuel input.

Relating Regulation to Cellular Energy State:

The overall regulation ensures the TCA cycle's activity is finely tuned to the cell's energy demands:

- High Energy State (High ATP/ADP, High NADH/NAD⁺): When the cell has abundant energy, the products (ATP, NADH, citrate, succinyl-CoA) accumulate and act as allosteric inhibitors, slowing down the cycle to conserve fuel.

-

Low Energy State (Low ATP/ADP, Low NADH/NAD⁺): When the cell needs energy, ATP and NADH levels drop, while ADP/AMP levels rise. These conditions act as allosteric activators.

Ca²⁺also acts as a key activator, signaling increased metabolic activity, especially in contracting muscles. - Substrate Availability: The availability of acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate also influences the flux through the cycle. The maintenance of oxaloacetate levels is crucial and involves anaplerotic reactions.

Amphibolic Nature and Anaplerotic Reactions

The TCA cycle is often presented as a purely catabolic pathway, but this is only half the story. The TCA cycle is, in fact, amphibolic, meaning it functions in both catabolic (breakdown) and anabolic (biosynthetic) processes.

1. Amphibolic Nature

The intermediates of the TCA cycle are not just steps on the way to CO₂; they are also crucial precursors for the biosynthesis of a wide variety of essential biomolecules.

- Catabolic Role: The primary catabolic role involves the complete oxidation of acetyl-CoA to CO₂, generating NADH, FADH₂, and GTP (ATP).

-

Anabolic Role (Examples of Intermediates as Precursors):

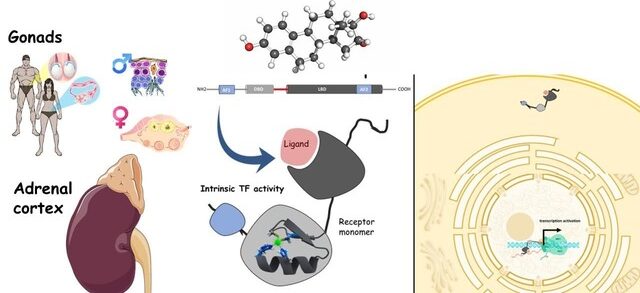

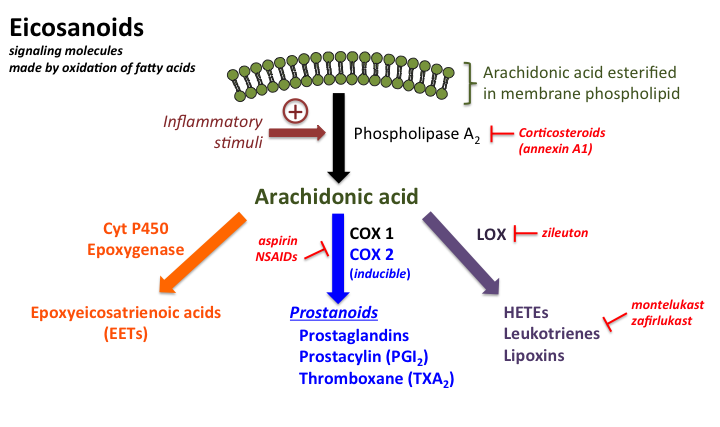

- Citrate: Can be transported out of the mitochondria to serve as a precursor for fatty acid and steroid biosynthesis.

- α-Ketoglutarate: A direct precursor for the synthesis of several non-essential amino acids (e.g., glutamate, glutamine) and purines.

- Succinyl-CoA: An intermediate used in the synthesis of porphyrins, which are components of heme (in hemoglobin).

- Fumarate & Oxaloacetate: Precursors for several non-essential amino acids. Oxaloacetate is also a starting point for gluconeogenesis (synthesis of glucose).

The diagram below illustrates some of these connections:

2. Anaplerotic Reactions

Because TCA cycle intermediates are frequently drawn off for biosynthesis, the cycle would quickly stop if these intermediates were not replenished. Reactions that replenish the intermediates of a metabolic pathway are called anaplerotic reactions (from Greek: "to fill up").

The most important anaplerotic reaction in mammals involves the replenishment of oxaloacetate:

-

Pyruvate Carboxylase: This enzyme catalyzes the carboxylation of pyruvate to oxaloacetate.

Pyruvate + HCO₃⁻ + ATP → Oxaloacetate + ADP + Pi

- Location: Primarily in the mitochondrial matrix of liver and kidney cells.

- Activator: This enzyme is allosterically activated by acetyl-CoA. This is a crucial regulatory link: when there's an abundance of acetyl-CoA but the cycle is low on oxaloacetate, pyruvate carboxylase steps in to produce more, ensuring the acetyl-CoA can be processed.

- Significance: This reaction is vital because if oxaloacetate is drained for anabolic processes (like gluconeogenesis), its replenishment ensures the TCA cycle can continue to operate.

Other anaplerotic reactions exist, such as replenishing intermediates from the breakdown of certain amino acids (e.g., glutamate to α-ketoglutarate). This highlights the incredible interconnectedness and flexibility of metabolism.

Biochemistry: TCA/Krebs Cycle Exam

Test your knowledge with these 40 questions.

TCA/Krebs Cycle Exam

Question 1/40

Exam Complete!

Here are your results, .

Your Score

38/40

95%