Genetic Code & : Chromosomes

I. Fundamental Concepts

A. The Structure and Components of Nucleic Acids: DNA & RNA

At the heart of all life is information, and in biological systems, this information is stored and transmitted by nucleic acids. There are two primary types: Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) and Ribonucleic Acid (RNA). Both are polymers made up of repeating monomer units called nucleotides.

1. The Nucleotide: The Building Block

Each nucleotide is composed of three main components:

A. A Pentose Sugar:

- In DNA: The sugar is 2'-deoxyribose (lacks a hydroxyl group at the 2' carbon).

- In RNA: The sugar is ribose (has a hydroxyl group at the 2' carbon).

- Significance: The presence or absence of this

2'-OHgroup is critical. The 2'-OH group in RNA makes it more reactive and less stable than DNA.

B. A Nitrogenous Base:

These are nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds. They fall into two categories:

- Purines (double-ring structure):

- Adenine (A)

- Guanine (G)

- Pyrimidines (single-ring structure):

- Cytosine (C)

- Thymine (T) (found only in DNA)

- Uracil (U) (found only in RNA, replaces Thymine)

Memory Aid

CUT the PY: Cytosine, Uracil, Thymine are Pyrimidines.

AG is PUre: Adenine, Guanine are Purines.

C. A Phosphate Group:

- Consists of a phosphorus atom bonded to four oxygen atoms.

- Attached to the 5' carbon of the pentose sugar.

- Significance: Phosphate groups give nucleic acids their negative charge and allow them to form the backbone of the polymer.

Combining these components:

- A base + sugar = Nucleoside (e.g., Adenosine, Guanosine, Cytidine, Uridine for RNA; Deoxyadenosine, Deoxyguanosine, Deoxycytidine, Deoxythymidine for DNA).

- A base + sugar + phosphate = Nucleotide (e.g., Adenosine Monophosphate (AMP), Deoxyadenosine Monophosphate (dAMP)). These are often referred to by their triphosphate forms (

ATP,GTP, etc.) when they are free in the cell, as these are the forms used for synthesis.

2. Polynucleotide Chains: The Backbone

Nucleotides are linked together to form long polynucleotide chains. This linkage occurs via a phosphodiester bond.

- A phosphodiester bond is formed between the 5'-phosphate group of one nucleotide and the 3'-hydroxyl group of the sugar of the adjacent nucleotide.

- This creates a sugar-phosphate backbone, with the nitrogenous bases extending off this backbone.

- Polarity: Because of this linkage, each polynucleotide strand has a distinct directionality or polarity:

- One end has a free phosphate group attached to the 5' carbon of the sugar (the 5' end).

- The other end has a free hydroxyl group attached to the 3' carbon of the sugar (the 3' end).

- Significance: All nucleic acid synthesis (DNA replication, RNA transcription) occurs in the

5' to 3'direction.

3. DNA vs. RNA: Key Differences

| Feature | DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid) | RNA (Ribonucleic Acid) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Long-term storage and transmission of genetic information | Gene expression (carrying genetic message, making proteins) |

| Sugar | 2'-deoxyribose | Ribose |

| Bases | Adenine (A), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C), Thymine (T) | Adenine (A), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C), Uracil (U) |

| Structure | Typically double-stranded helix | Typically single-stranded, but can fold into complex 3D shapes |

| Stability | Very stable (due to deoxyribose and double helix) | Less stable (due to ribose and often single-stranded) |

| Location | Primarily in the nucleus (eukaryotes), mitochondria, chloroplasts | Nucleus, cytoplasm, ribosomes (multiple forms) |

4. The DNA Double Helix: Watson and Crick Model

The most iconic structure in molecular biology is the DNA double helix, elucidated by Watson and Crick (with crucial contributions from Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins).

- Two Polynucleotide Strands: DNA consists of two long polynucleotide strands wound around each other to form a right-handed double helix.

- Antiparallel Orientation: The two strands run in opposite directions; one strand runs

5' to 3', and its complementary strand runs3' to 5'. This is crucial for replication and transcription. - Sugar-Phosphate Backbone: The sugar-phosphate backbones are on the outside of the helix, forming the structural framework.

- Nitrogenous Bases Inside: The nitrogenous bases are stacked in the interior of the helix, like steps on a spiral staircase.

- Complementary Base Pairing: This is the most critical feature. Bases on one strand form specific hydrogen bonds with bases on the opposite strand:

- Adenine (A) always pairs with Thymine (T) via two hydrogen bonds (

A=T). - Guanine (G) always pairs with Cytosine (C) via three hydrogen bonds (

G≡C).

- Adenine (A) always pairs with Thymine (T) via two hydrogen bonds (

- Significance: This pairing ensures that the two strands are complementary, meaning the sequence of one strand dictates the sequence of the other. It's vital for accurate DNA replication and repair.

- Hydrogen Bonds: These weak bonds hold the two strands together. While individually weak, their collective strength along the entire DNA molecule provides significant stability.

- Major and Minor Grooves: The helical twisting of the DNA strands creates two grooves on the surface: a wider major groove and a narrower minor groove. These grooves are important for protein binding, allowing regulatory proteins to access and interact with specific base sequences without having to unwrap the helix.

B. The Central Dogma of Molecular Biology

The concept of the Central Dogma, first proposed by Francis Crick, describes the fundamental flow of genetic information within a biological system. It states:

DNA → RNA → Protein

Let's break down each arrow:

- DNA → DNA (Replication):

- The process by which a cell makes an exact copy of its entire DNA content.

- Essential for cell division, ensuring that each daughter cell receives a complete set of genetic instructions.

- Occurs in the nucleus (eukaryotes) during the S phase of the cell cycle.

- DNA → RNA (Transcription):

- The process by which the genetic information encoded in a gene (segment of DNA) is copied into an RNA molecule.

- This RNA molecule acts as an intermediary, carrying the genetic message from the DNA (which stays in the nucleus) to the protein-synthesizing machinery in the cytoplasm.

- Occurs in the nucleus (eukaryotes).

- RNA → Protein (Translation):

- The process by which the genetic code carried by messenger RNA (mRNA) is decoded to synthesize a specific protein.

- This is where the "language" of nucleic acids (sequence of nucleotides) is translated into the "language" of proteins (sequence of amino acids).

- Occurs in the cytoplasm on ribosomes.

Overall Significance of the Central Dogma:

- It defines the sequential flow of genetic information that ultimately leads to the production of functional proteins, which carry out nearly all cellular processes and form the structural components of cells.

- It provides a framework for understanding how genes control traits and how mutations can lead to disease.

Brief Mention of Exceptions:

While the Central Dogma describes the primary flow, there are some important exceptions and elaborations:

- Reverse Transcription (RNA → DNA): Some viruses (retroviruses like HIV) use an enzyme called reverse transcriptase to synthesize DNA from an RNA template. This newly made DNA can then be integrated into the host genome.

- RNA Replication (RNA → RNA): Some RNA viruses replicate their RNA directly, without a DNA intermediate.

- RNA as Genetic Material: For many viruses, RNA, not DNA, serves as the primary genetic material.

- Non-coding RNAs: Not all RNA is translated into protein. Many RNA molecules (like tRNA, rRNA, miRNA, siRNA) have direct structural, catalytic, or regulatory roles.

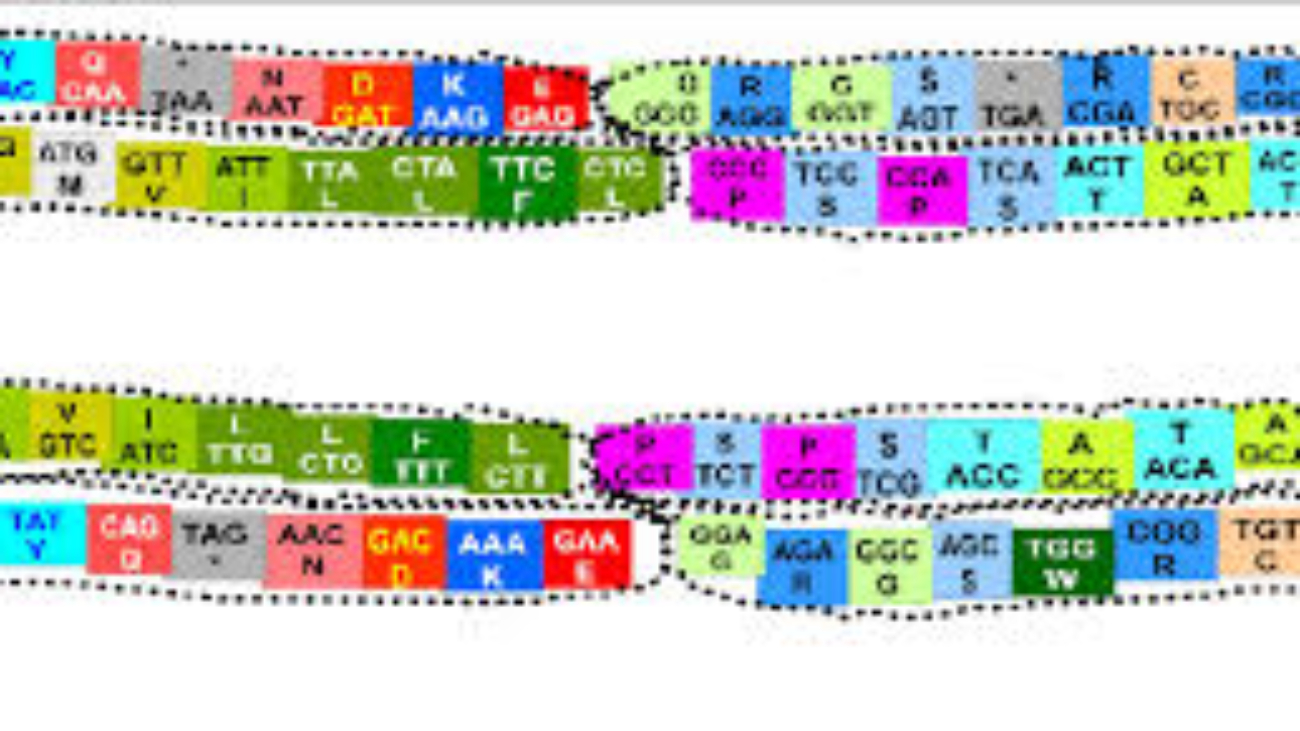

C. Elaboration on the Characteristics and Significance of the Genetic Code

The genetic code is the set of rules by which information encoded within genetic material (DNA or RNA sequences) is translated into proteins (amino acid sequences) by living cells. It's essentially the biological dictionary that translates between the language of nucleotides and the language of amino acids.

Key characteristics:

1. Codon: The Fundamental Unit of the Genetic Code

- Definition: A codon is a sequence of three successive nucleotides in an mRNA molecule that specifies a particular amino acid or signals termination of protein synthesis.

- Triplet Nature: Each codon consists of three "letters" (bases). Since there are four possible bases (A, U, G, C) and each codon is a triplet, there are

4 x 4 x 4 = 64possible codons. - Reading Frame: The sequence of codons in an mRNA molecule is read in a specific order, known as the reading frame. The reading frame is established by the start codon (usually

AUG). If the reading frame is shifted by even one nucleotide (e.g., due to an insertion or deletion mutation), it will alter every subsequent codon, leading to a completely different amino acid sequence (a "frameshift" mutation).

2. Degeneracy (Redundancy) of the Genetic Code

- Definition: The genetic code is degenerate (or redundant) because most amino acids are specified by more than one codon.

- Example: Leucine is encoded by six different codons (

UUA,UUG,CUU,CUC,CUA,CUG). Serine is also encoded by six. Conversely, Methionine (AUG) and Tryptophan (UGG) are encoded by only a single codon. - Significance:

- Protection against mutations: Degeneracy provides a buffer against the potentially harmful effects of point mutations (single nucleotide changes). If a mutation changes one base in a codon, it might still code for the same amino acid, thus having no effect on the protein sequence (a "silent mutation").

- Wobble Hypothesis: This phenomenon is partly explained by the "wobble hypothesis," which states that the pairing between the third base of the mRNA codon and the first base of the tRNA anticodon is less stringent than the first two bases. This allows a single tRNA molecule to recognize more than one codon.

3. Unambiguousness of the Genetic Code

- Definition: The genetic code is unambiguous because each codon specifies only one amino acid (or a stop signal).

- Example: While

UUAandUUGboth code for Leucine (degeneracy), neither of them will ever code for, say, Valine or Serine. - Significance: This ensures that the genetic message is translated accurately and consistently. If a codon could specify multiple amino acids, protein synthesis would be chaotic and unreliable.

4. Universality of the Genetic Code

- Definition: The genetic code is (almost) universal, meaning that the same codons specify the same amino acids in nearly all organisms, from bacteria to humans.

- Example: The codon

GGCspecifies Glycine in E. coli, in plants, in animals, and in fungi. - Significance:

- Evidence for common ancestry: This universality is one of the strongest pieces of evidence for the common evolutionary origin of all life on Earth.

- Genetic engineering: It allows for genetic engineering applications, where a gene from one organism (e.g., human insulin gene) can be inserted into another organism (e.g., bacteria) and be correctly expressed to produce a functional protein.

- Minor Exceptions: While largely universal, minor variations have been found in the mitochondrial genomes of some organisms and in some single-celled eukaryotes (e.g., ciliates). However, these exceptions are rare and do not undermine the overall principle.

5. Start and Stop Codons

Specific codons play crucial roles in initiating and terminating protein synthesis:

Start Codon (Initiation)

The Codon: Primarily AUG.

Codes for: Methionine (Met).

Dual Role: In eukaryotes, the first AUG sets the reading frame and signals start. This methionine is typically removed later. In bacteria, it codes for N-formylmethionine.

Significance: Establishes the correct reading frame for the entire mRNA sequence, ensuring all subsequent codons are read correctly.

Stop Codons (Termination)

The Codons: UAA, UAG, UGA.

Codes for: No amino acid (Nonsense codons).

Mechanism: When a ribosome encounters these, it recruits release factors, causing the polypeptide chain to be released and the translation complex to dissociate.

Significance: Defines the end of the protein sequence, ensuring proteins are the correct length and composition.

Summary of the Genetic Code

The genetic code is a triplet, degenerate (redundant), unambiguous, and nearly universal code. It uses specific start and stop signals to ensure accurate and efficient protein synthesis. Its elegant design allows for both precision and a degree of robustness against mutations, crucial for life.

Understanding these characteristics is fundamental because it explains how the relatively simple language of A, U, G, C nucleotides translates into the complex and diverse world of proteins, which perform virtually all cellular functions and define an organism's physiology.

DNA Replication: Mechanism and Fidelity

DNA replication is the process by which a cell makes an exact copy of its entire DNA. This is a fundamental process for all life, essential for cell division, growth, repair, and reproduction. It ensures that each daughter cell receives a complete and identical set of genetic instructions.

A. Key Steps and Enzymes Involved in DNA Replication

DNA replication is a highly coordinated and complex process involving numerous enzymes and proteins. It occurs in a semi-conservative manner.

1. Semi-Conservative Replication

- This means that each new DNA molecule consists of one "old" strand (from the original DNA molecule) and one "newly synthesized" strand.

- Significance: This mechanism ensures high fidelity because the old strand serves as a template for the new strand, guiding base pairing and reducing errors.

2. Origins of Replication

- Replication doesn't start randomly. It begins at specific, sequence-defined locations along the DNA molecule called origins of replication.

- Eukaryotes: Have multiple origins of replication along each chromosome, allowing for faster replication of large genomes.

- Prokaryotes: Typically have a single origin of replication on their circular chromosome.

3. Unwinding the DNA Double Helix

- Helicase: This enzyme unwinds and separates the two parental DNA strands by breaking the hydrogen bonds between complementary base pairs. This creates a Y-shaped structure called a replication fork.

- Single-Strand Binding Proteins (SSBs): These proteins bind to the separated single DNA strands, preventing them from re-annealing (coming back together) and protecting them from degradation.

- Topoisomerase (DNA Gyrase in bacteria): As helicase unwinds the DNA, it creates supercoiling (over-winding) ahead of the replication fork. Topoisomerases relieve this tension by cutting one or both DNA strands, allowing them to uncoil, and then rejoining them. Without topoisomerase, replication would stall.

4. Initiating New Strand Synthesis

Primase: DNA polymerase (the enzyme that synthesizes new DNA) cannot start a new strand from scratch; it can only add nucleotides to an existing 3'-OH group. Therefore, primase (an RNA polymerase) synthesizes a short RNA segment called an RNA primer complementary to the DNA template. This primer provides the necessary 3'-OH group.

5. Elongation: DNA Synthesis by DNA Polymerase

DNA Polymerase: This is the primary enzyme responsible for synthesizing new DNA strands.

- It adds deoxyribonucleotides (

dATP,dCTP,dGTP,dTTP) one by one to the 3' end of the growing strand, forming phosphodiester bonds. - It always synthesizes new DNA in the

5' to 3'direction. - It uses the parental strand as a template, following the rules of complementary base pairing (A with T, G with C).

Leading Strand

One of the template strands is oriented 3' to 5' relative to the replication fork.

DNA polymerase can synthesize the new complementary strand continuously in the 5' to 3' direction, moving towards the replication fork. Only one primer is needed.

Lagging Strand

The other template strand is oriented 5' to 3' relative to the replication fork.

Since DNA polymerase can only synthesize in the 5' to 3' direction, it must synthesize this strand discontinuously, in short fragments, moving away from the replication fork.

These short fragments are called Okazaki fragments. Each fragment requires its own RNA primer.

6. Removing RNA Primers and Ligation

- DNA Polymerase I (prokaryotes) / RNase H (eukaryotes) & DNA Pol δ: These enzymes remove the RNA primers.

- DNA Polymerase: Fills in the gaps left by the removed primers with DNA nucleotides.

- DNA Ligase: After the gaps are filled, DNA ligase forms the final phosphodiester bond, joining the Okazaki fragments and sealing any nicks in the sugar-phosphate backbone.

Simplified Overview of Replication Fork Activity

Imagine the replication fork opening like a zipper. On one side (leading strand), DNA polymerase zips along continuously. On the other side (lagging strand), DNA polymerase makes short pieces (Okazaki fragments), then jumps back, makes another piece, and so on. These fragments are later connected.

B. Mechanisms Ensuring the Fidelity of DNA Replication

The accuracy of DNA replication is astounding, with an error rate of about 1 in 109 to 1010 base pairs. This incredible fidelity is critical because errors (mutations) can lead to dysfunctional proteins, genetic diseases, or cancer.

The 3 Pillars of Fidelity

-

Base Pairing Specificity:

The primary mechanism is the stringent requirement for complementary base pairing. Hydrogen bonding provides stability to correct pairs; incorrect pairings are unstable.

-

Proofreading by DNA Polymerase:

DNA polymerase has a

3' to 5'exonuclease activity. If it adds an incorrect nucleotide, it detects the mismatch, pauses, removes the wrong base, and re-synthesizes the segment. -

Mismatch Repair Mechanisms:

A post-replication system. Enzymes scan newly synthesized DNA for errors missed by proofreading. They excise the incorrect segment (distinguishing new strand from old via methylation or nicks) and fill it correctly. Defects here can lead to cancers like HNPCC.

Summary of DNA Replication

DNA replication is a highly precise, semi-conservative process involving a coordinated effort of many enzymes. It proceeds bidirectionally from origins of replication, synthesizing leading and lagging strands. The remarkable fidelity is maintained through stringent base pairing, DNA polymerase's proofreading activity, and post-replication mismatch repair systems.

Gene Expression: Transcription and RNA Processing

Transcription is the process by which the genetic information encoded in a gene (a specific segment of DNA) is copied into an RNA molecule. This RNA molecule then serves various functions, most notably as messenger RNA (mRNA) carrying the code for protein synthesis.

A. Description of the Process of Transcription

1. Template vs. Non-Template Strands

- DNA as a Template (Antisense Strand): Only one of the two DNA strands serves as the template for RNA synthesis.

- Non-Template Strand (Coding/Sense Strand): Its sequence is virtually identical to the newly synthesized RNA molecule (except RNA has Uracil instead of Thymine).

- Significance: RNA polymerase reads the template in the

3' to 5'direction, synthesizing RNA in the5' to 3'direction.

2. The Key Enzyme: RNA Polymerase

RNA polymerase catalyzes the synthesis of RNA from DNA. Unlike DNA polymerase, it does not require a primer.

- RNA Polymerase I: Synthesizes ribosomal RNA (rRNA).

- RNA Polymerase II: Synthesizes messenger RNA (mRNA) and some snRNAs. (Focus of gene expression).

- RNA Polymerase III: Synthesizes transfer RNA (tRNA) and 5S rRNA.

3. Stages of Transcription

a) Initiation

- Promoter Recognition: RNA polymerase II and transcription factors bind to a specific DNA sequence called the promoter (upstream of the start site).

- Transcription Bubble: The DNA helix is unwound to form a bubble.

- Start: Synthesis begins using ribonucleotides (ATP, UTP, CTP, GTP).

b) Elongation

- RNA polymerase moves along the template

3' to 5'. - It adds ribonucleotides to the 3' end of the growing RNA (synthesizing

5' to 3'). - The new RNA detaches from the template as the enzyme moves downstream.

c) Termination

- Transcription continues until terminator sequences are encountered.

- The RNA transcript and polymerase are released from the DNA.

B. Explaining the Processing of Eukaryotic mRNA (Post-Transcriptional Modification)

Unlike prokaryotic mRNA, eukaryotic primary transcripts (pre-mRNA) undergo extensive modifications in the nucleus before export.

Addition of a 5' Cap

A modified guanine (7-methylguanosine) is added to the 5' end via a 5'-5' triphosphate bridge.

Functions: Protects from degradation, helps ribosome binding, facilitates nuclear export.

Addition of a Poly-A Tail

Poly-A polymerase adds 50-250 Adenine (A) nucleotides to the 3' end.

Functions: Increases stability/lifespan, aids translation initiation, aids export.

Splicing

Removal of non-coding Introns and joining of coding Exons. Catalyzed by the spliceosome (snRNPs).

Functions: Produces mature mRNA with continuous coding sequence.

Alternative Splicing and Protein Diversity

Definition: A crucial mechanism where a single gene can produce multiple different protein products by including different combinations of exons.

Significance: Dramatically increases the coding capacity of the genome. Our ~20,000 genes can generate a much larger number of proteins, contributing to biological complexity.

Summary of Transcription & Processing

Transcription faithfully copies genetic information from DNA to RNA via RNA polymerase. In eukaryotes, pre-mRNA undergoes 5' capping, 3' polyadenylation, and splicing to become mature mRNA. Alternative splicing adds complexity, allowing one gene to encode multiple protein variants.

Next Step: Translation (decoding mRNA into protein).

Translation (Protein Synthesis)

Translation is the process by which the genetic code within a messenger RNA (mRNA) molecule is used to direct the synthesis of a specific protein (polypeptide chain). This complex process occurs in the cytoplasm and involves a sophisticated molecular machinery.

A. Key Components Involved in Translation

Several molecular players are essential for the accurate and efficient synthesis of proteins:

1. Ribosomes

- Structure: Complex molecular machines composed of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and proteins. Consist of a large subunit and a small subunit, which only come together during translation.

- Function: The sites of protein synthesis. They provide a framework for mRNA and tRNAs to interact, catalyze peptide bond formation, and move along the mRNA.

The Ribosomal Binding Sites (APE)

Where incoming aminoacyl-tRNAs (carrying their amino acid) first bind.

Where the tRNA holding the growing polypeptide chain is located.

Where "spent" tRNAs (that have delivered their amino acid) are released.

2. tRNA (Transfer RNA)

- Structure: Small RNA molecules that fold into a cloverleaf secondary structure and an L-shaped tertiary structure.

- Function: Molecular adaptors bridging codons and amino acids. Contains:

- Anticodon: Three-nucleotide sequence complementary to a specific mRNA codon.

- Amino Acid Attachment Site: At the 3' end, where the specific amino acid is covalently attached.

3. Other Essential Components

- Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases: Enzymes that "charge" tRNAs by attaching the correct amino acid. Critical for fidelity.

- mRNA (Messenger RNA): Carries the genetic message (codons) from the nucleus to the ribosome.

- Amino Acids: The 20 building blocks linked to form proteins.

- Protein Factors: Initiation, Elongation, and Release factors that regulate the process.

- Energy (GTP, ATP): Required for tRNA charging, assembly, and translocation.

B. Outline the Stages of Translation

Translation proceeds through three main stages:

1. Initiation

Goal: Assemble machinery at the start codon.

- Components Assemble: Small ribosomal subunit binds to mRNA (scans from 5' cap to find

AUG). - Initiator tRNA: Binds to the start codon (

AUG) in the P site. Carries Methionine (Met). - Large Subunit Joins: Completes the ribosome. Initiator tRNA is now correctly positioned in the P site.

2. Elongation

Goal: Growth of polypeptide chain via sequential addition of amino acids.

- Codon Recognition: Incoming aminoacyl-tRNA binds to the A site (requires GTP).

- Peptide Bond Formation: Peptidyl transferase (rRNA ribozyme) catalyzes a bond between the amino acid in A site and the chain in P site. The chain transfers to the A site. P site tRNA becomes empty ("uncharged").

- Translocation: Ribosome moves one codon (

5' to 3'). Uncharged tRNA moves to E site and exits. Growing chain moves to P site. A site is now empty for the next tRNA.

3. Termination

Goal: Release the completed protein.

- Stop Codon Recognition: Stop codon (

UAA,UAG,UGA) enters A site. No tRNA matches this. - Release Factors: Proteins bind to the stop codon.

- Polypeptide Release: Peptidyl transferase hydrolyzes the bond, releasing the polypeptide chain.

- Disassembly: Ribosome dissociates and components are recycled.

C. Discussion of Post-Translational Modifications and Protein Targeting

Once synthesized, the polypeptide is not always immediately functional. It often undergoes modifications and sorting.

1. Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs)

Chemical modifications critical for folding, stability, and activity.

- Folding: Into 3D structure (often via chaperones).

- Cleavage/Proteolysis: Removal of signal peptides or activation (e.g., proinsulin → insulin).

- Glycosylation: Addition of sugar chains (cell recognition).

- Phosphorylation: Addition of phosphate (on/off switch).

- Disulfide Bonds: Covalent bonds between cysteines (stability).

- Other: Acetylation, Methylation, Ubiquitination.

2. Protein Targeting (Sorting)

Proteins must be delivered to the correct compartment using Signal Peptides (targeting sequences).

- Co-translational Translocation (ER pathway): Proteins for secretion, membranes, or lysosomes start in cytoplasm but are directed to the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) during translation.

- Post-translational Translocation: Proteins for mitochondria, nucleus, etc., are fully translated in cytoplasm then imported.

- Cytosolic Proteins: Lack targeting sequences and remain in the cytoplasm.

Summary of Translation

Translation is the elegant process where the mRNA template is read by ribosomes, with the help of tRNA adaptors, to synthesize a polypeptide chain according to the genetic code. It proceeds through initiation, elongation, and termination. The newly synthesized polypeptide then often undergoes crucial post-translational modifications and is accurately targeted to its final cellular destination.

Chromosomes and Karyotype

Chromosomes are highly organized structures found inside the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. They are made of DNA tightly coiled around proteins called histones, which support its structure. Chromosomes serve to keep DNA tightly wrapped, preventing it from becoming tangled and protecting it from damage during cell division.

A. Definition and Structure of Chromosomes

Definition: Chromosome

A thread-like structure of nucleic acids and protein found in the nucleus of most living cells, carrying genetic information in the form of genes. In eukaryotes, they are linear; in prokaryotes, they are typically circular.

Eukaryotic Chromosome Structure

The hierarchy of packaging allows 2 meters of DNA to fit into a microscopic nucleus:

-

1DNA Double Helix: The fundamental component containing genetic instructions. (Negatively charged).

-

2Histones: Small, positively charged proteins (H1, H2A, H2B, H3, H4) that attract the negative DNA.

-

3Nucleosome: The basic unit ("beads on a string"). DNA wound around a core of eight histone proteins.

-

4Chromatin Fiber (30-nm): Nucleosomes coil into a thicker fiber, stabilized by H1 histone.

-

5Looped Domains & Metaphase Chromosome: Loops attach to a protein scaffold. During cell division (Metaphase), these condense into the visible X-shaped structures consisting of two sister chromatids.

Key Chromosome Regions

Centromere

A constricted region that serves as the attachment point for spindle fibers. It ensures sister chromatids separate correctly. Divides chromosome into p-arm (short) and q-arm (long).

Telomeres

Protective caps at the ends of linear chromosomes (repetitive DNA). They protect genes from degradation and fusion. They shorten with each division, contributing to aging.

B. Homologous Chromosomes, Autosomes, and Sex Chromosomes

Diploid vs. Haploid

- Diploid (2n): Cells with two complete sets of chromosomes (one from each parent). Somatic cells (e.g., 46 in humans).

- Haploid (n): Cells with a single set of unpaired chromosomes. Gametes (e.g., 23 in humans).

Homologous Chromosomes

- Definition: A pair of chromosomes (one from mother, one from father) similar in size, shape, and gene sequence.

- Significance: During meiosis, they pair up and exchange genetic material (crossing over), creating diversity.

Autosomes vs. Sex Chromosomes

| Type | Description | In Humans |

|---|---|---|

| Autosomes | Chromosomes that are not sex chromosomes. Carry most traits. | 22 pairs (1-22) |

| Sex Chromosomes | Determine biological sex. X carries many genes; Y is gene-poor (male development). | 1 pair (XX Female / XY Male) |

C. Definition and Significance of Karyotype Analysis

Definition: A karyotype is an organized profile (photograph) of a person's chromosomes. Cells are arrested in metaphase, stained, and arranged by size (1-22, then X/Y).

Significance of Karyotype Analysis

A powerful diagnostic tool with several key applications:

1. Diagnosis of Chromosomal Disorders

Numerical Abnormalities (Aneuploidies)

- Trisomy: Extra copy (e.g., Trisomy 21 / Down Syndrome).

- Monosomy: Missing copy (e.g., Monosomy X / Turner Syndrome).

Structural Abnormalities

- Deletions/Duplications: Loss or gain of segments.

- Translocations: Exchange between non-homologous chromosomes (e.g., Philadelphia chromosome).

- Inversions/Rings: Reversal or circular fusion.

2. Other Clinical Applications

- Prenatal Diagnosis: Detecting abnormalities via amniocentesis.

- Infertility/Miscarriage: Investigating parental chromosomal causes.

- Cancer Diagnosis: Classifying cancers (e.g., CML) and predicting treatment response.

- Sex Determination: Confirming chromosomal sex in ambiguous cases.

Summary of Chromosomes & Karyotype

Chromosomes are highly organized carriers of genetic info, composed of DNA and histones. They exist as homologous pairs (autosomes + sex chromosomes). Karyotype analysis provides a visual map of these chromosomes, serving as an invaluable tool for detecting numerical (Trisomy/Monosomy) and structural abnormalities crucial for diagnosing genetic diseases and cancer.

Principles of Inheritance

Inheritance, or heredity, is the process by which genetic information is passed on from parent to child. It explains why offspring resemble their parents but are not identical to them. Our understanding of inheritance began with the foundational work of Gregor Mendel in the 19th century.

A. Basic Terminology in Genetics

Before delving into Mendel's laws, it's crucial to understand some fundamental terms:

- Gene: A segment of DNA on a chromosome that codes for a specific trait (e.g., eye color).

- Allele: Different forms or variations of a particular gene (e.g., blue vs. brown eye allele).

- Locus: The specific physical location of a gene on a chromosome.

- Dominant Allele (A): Expresses phenotype even when heterozygous. Masks recessive alleles.

- Recessive Allele (a): Expressed only when homozygous recessive. Masked by dominant alleles.

- Genotype: The genetic makeup (e.g.,

BB,Bb,bb). - Phenotype: The observable physical characteristics (e.g., Brown eyes), resulting from genotype + environment.

- Homozygous: Two identical alleles (

BBorbb). - Heterozygous: Two different alleles (

Bb).

Generations: P (Parental), F1 (First Filial/Offspring), F2 (Second Filial/Grandchildren).

B. Mendel's Laws of Inheritance

1. Law of Segregation

Statement: During gamete formation, the two alleles for a gene separate so that each gamete receives only one.

Mechanism: Anaphase I & II of Meiosis.

Implication: Offspring get one allele from each parent.

2. Law of Independent Assortment

Statement: Genes for different traits assort independently (e.g., seed color doesn't affect seed shape).

Mechanism: Random orientation of homologous pairs during Metaphase I.

Implication: Increased genetic variation.

3. Law of Dominance

Statement: In a heterozygote, the dominant allele conceals the recessive allele.

Implication: Heterozygotes (Bb) have the same phenotype as Homozygous Dominant (BB).

C. Punnett Squares

A graphical way to predict genotypes and phenotypes.

Example: Monohybrid Cross (Single Gene)

Scenario: Cross two heterozygotes (Bb x Bb). Brown (B) is dominant.

| B | b | |

|---|---|---|

| B | BB (Brown) |

Bb (Brown) |

| b | Bb (Brown) |

bb (Blue) |

Genotypic Ratio: 1 BB : 2 Bb : 1 bb

Phenotypic Ratio: 3 Brown : 1 Blue

Example: Dihybrid Cross (Two Genes)

Scenario: RrYy x RrYy (Round/Yellow).

- Classic Phenotypic Ratio:

9:3:3:1 - (9 Round Yellow : 3 Round Green : 3 Wrinkled Yellow : 1 Wrinkled Green).

D. Beyond Mendelian Inheritance

Incomplete Dominance

Heterozygous phenotype is intermediate (blended).

Ex: Red (RR) x White (WW) = Pink (RW) flowers.

Codominance

Both alleles are fully expressed (no blending).

Ex: Blood Type AB (Both A and B antigens present).

Polygenic Inheritance

Traits determined by cumulative effect of multiple genes (continuous range).

Ex: Height, Skin Color.

Epistasis

One gene masks the expression of another.

Ex: Labrador pigment gene masks fur color gene.

Sex-Linked Inheritance

Traits determined by genes on sex chromosomes (X or Y). Males (XY) are more affected by X-linked recessive traits (e.g., Color Blindness, Hemophilia) because they only have one X chromosome.

E. Pedigree Analysis

Pedigrees are "family trees" used to track inheritance, determine modes of transmission, and predict genetic risk.

1. Standardized Pedigree Symbols

2. Analyzing Patterns of Inheritance

a. Autosomal Dominant

Vertical- Affected individuals in every generation.

- Affected offspring must have at least one affected parent.

- Males and females affected equally.

- Example: Huntington's disease.

b. Autosomal Recessive

Horizontal / Skipping- Often skips generations (Affected child, Unaffected parents).

- Males and females affected equally.

- Increased incidence with Consanguinity.

- Example: Cystic Fibrosis.

c. X-Linked Recessive

Sex-Biased- More males affected than females.

- Affected sons usually have unaffected mothers (carriers).

- No father-to-son transmission.

- Example: Hemophilia.

Analysis Strategy: Where to Start?

- Look for skipping generations: If yes → Recessive. If no → Dominant.

- Look at sex distribution: If mostly males → X-linked Recessive. If equal → Autosomal.

- Check Father-to-Son: If an affected father has an affected son, it cannot be X-linked recessive.

Summary of Inheritance & Pedigrees

Inheritance explains trait transmission via Mendel's laws (Segregation, Independent Assortment, Dominance). Real-world genetics often involves complexity like incomplete dominance or sex-linkage. Pedigree analysis uses standardized symbols to track these patterns, allowing us to determine if a trait is Dominant (vertical), Recessive (skipping), or X-linked (males affected), which is vital for genetic counseling and risk prediction.

Biochemistry: Genetic Code & Chromosomes

Test your knowledge with these 30 questions.

Genetic Code & Chromosomes Quiz

Question 1/30

Quiz Complete!

Here are your results, .

Your Score

27/30

90%