Homeostasis: Maintaining the Internal Balance

Homeostasis

Imagine you're driving a car, aiming to maintain a constant speed of 60 mph. You press the gas going uphill and ease off going downhill. Your goal is to keep that speed constant despite external changes. That's essentially what your body does, constantly, for hundreds of variables.

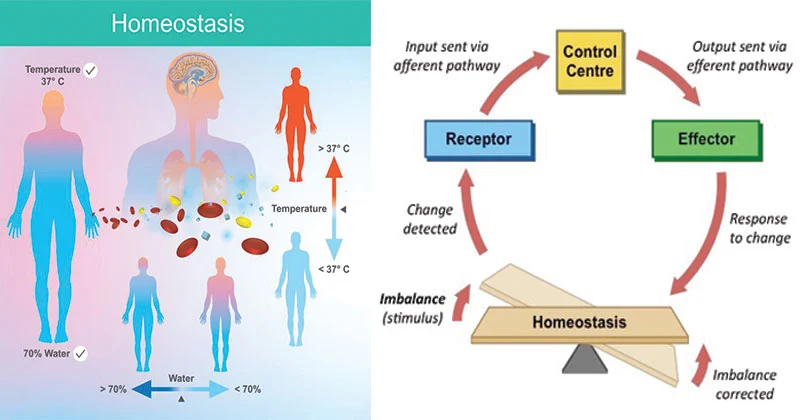

Homeostasis (from Greek "homoios" meaning "similar" and "stasis" meaning "standing still") is the ability of an organism to maintain a relatively stable internal environment despite continuous changes in the external environment. It's not a static state, but a dynamic equilibrium where conditions fluctuate within narrow, acceptable limits around a set point.

Many physiologists translate this into the saying, “constantly changing to stay the same.” The ability of the human body to quickly adapt to any changes and to re-establish stability is the essence of homeostasis.

The Importance of Homeostasis

Survival itself depends on the body's ability to maintain this internal balance. Deviations outside the normal range can impair cell function, leading to disease or death.

Enzyme and Protein Function

Almost all biochemical reactions are catalyzed by enzymes (proteins), which are highly sensitive to their environment.

Impact of Imbalance: Deviations in temperature or pH can denature enzymes, altering their 3D shape and halting vital metabolic pathways.

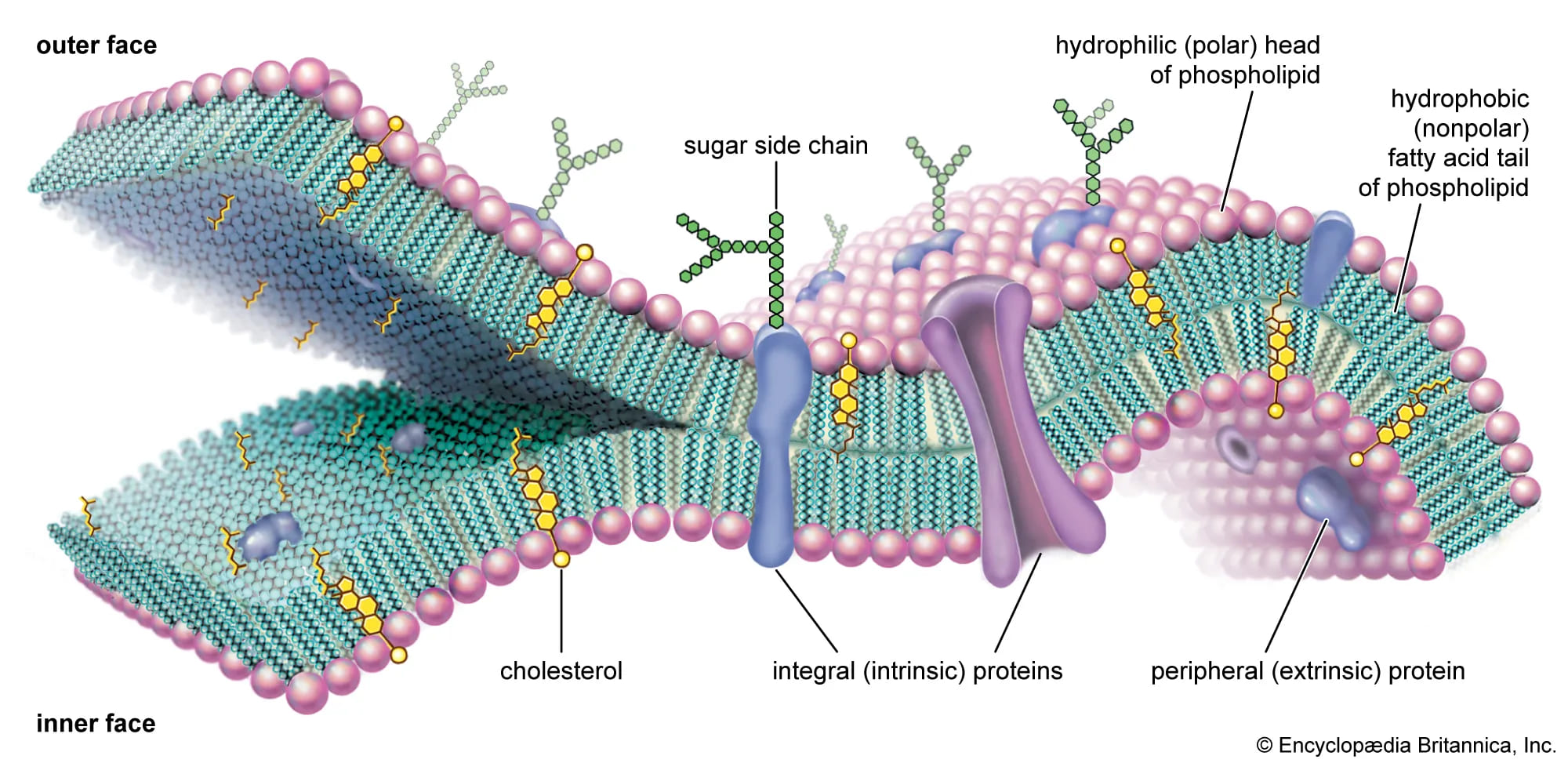

Cellular Integrity and Volume

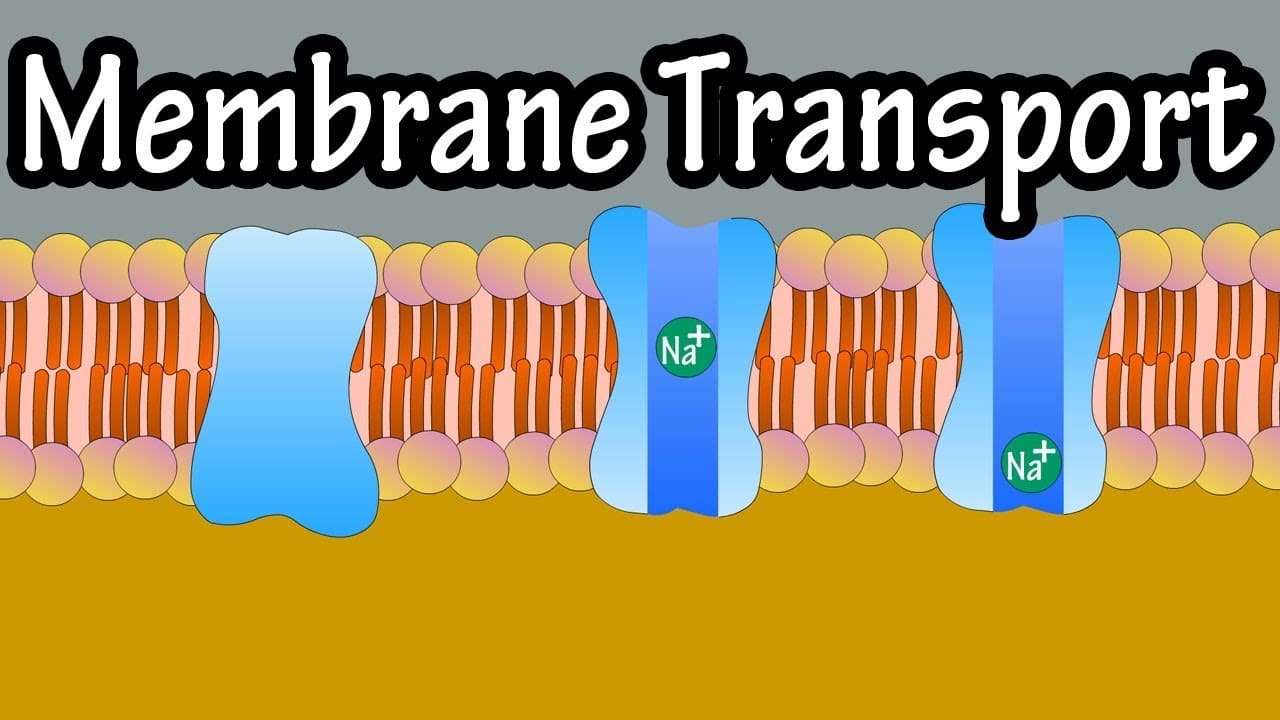

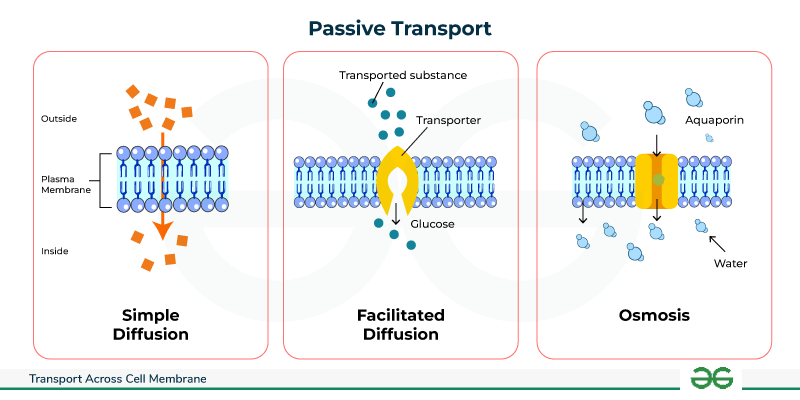

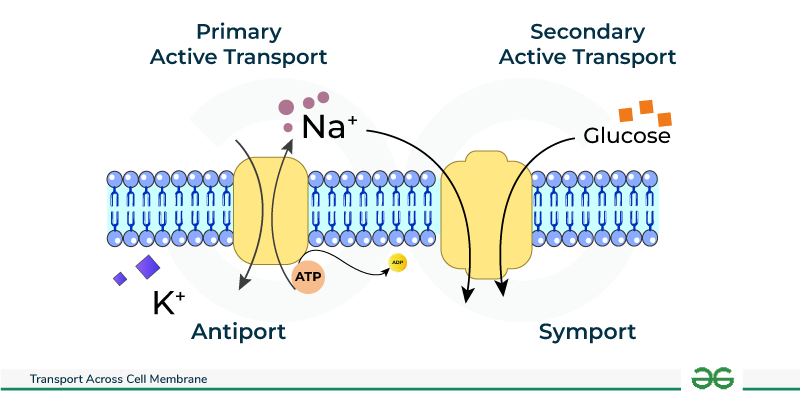

The cell membrane's selective permeability and active transport mechanisms are critical for maintaining appropriate solute concentrations.

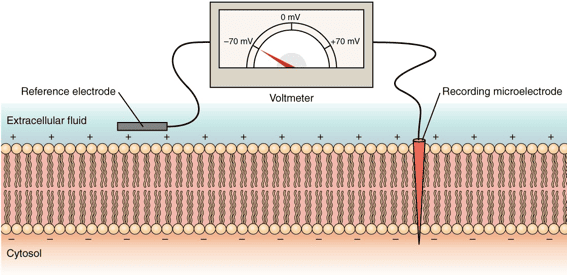

Impact of Imbalance: Changes in extracellular fluid osmolarity can cause cells to swell and burst (lysis) or shrink and die (crenation). Disrupted ion gradients incapacitate nerve and muscle function.

Efficient Communication Systems

The nervous and endocrine systems require specific conditions to transmit signals effectively.

Impact of Imbalance: Improper electrolyte balance (Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺) can lead to severe nerve and muscle dysfunction, including seizures, paralysis, and cardiac arrhythmias.

Energy Production (ATP)

Cells require a continuous supply of oxygen and nutrients, and efficient removal of waste, to produce ATP.

Impact of Imbalance: Oxygen deprivation (hypoxia) leads to a cellular energy crisis and buildup of lactic acid. Accumulation of wastes like CO₂ can become toxic and alter pH, leading to organ failure.

Immune System Function

Immune cells and proteins need stable conditions to effectively fight off pathogens without harming healthy tissues.

Impact of Imbalance: Uncontrolled fever can become detrimental to immune cells themselves. Chronic stress and elevated cortisol can suppress the immune system.

Examples of Homeostatically Regulated Variables

The body tightly regulates hundreds of variables to maintain this dynamic equilibrium. Key examples include:

- Body temperature

- Blood pressure

- Blood glucose levels

- Blood pH

- Oxygen and carbon dioxide levels

- Water balance

- Ion concentrations (Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺)

Homeostasis is Maintained by Feedback Loops

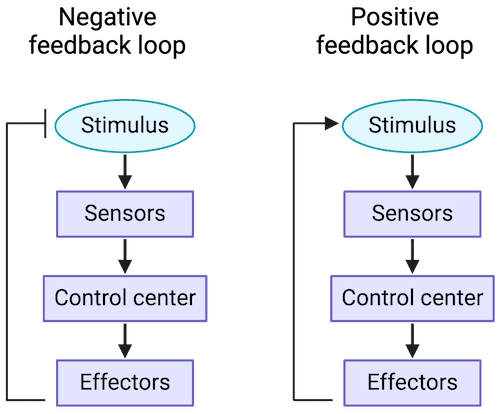

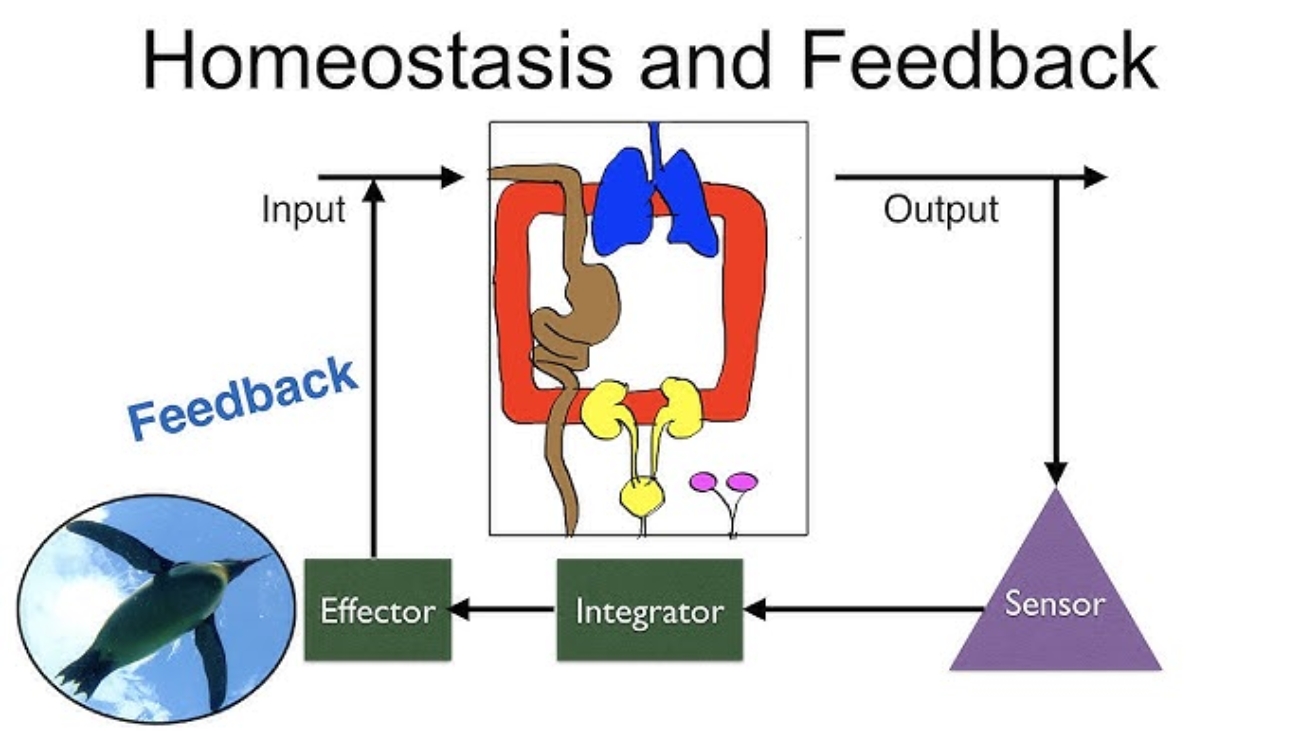

The primary way the human body maintains homeostasis is with the use of feedback loops. A feedback loop is a mechanism that allows for continual assessment of the body’s physiology and a way to correct various elements if they should go out of balance. There are two types of feedback loops: negative and positive.

Negative Feedback Loop

The response opposes (or negates) the original stimulus. This is by far the most common type in the human body.

Positive Feedback Loop

The response augments (or intensifies) the original stimulus. The cycle repeats until it is broken. This type is very rare but critically important.

Parameters and Set Points

For any feedback loop, there is a parameter that is being monitored, and it has a set point, or a ‘normal range’ in which it exists when the body is in balance. The stimulus that starts the feedback loop is a change in that parameter that pushes it above or below its normal set point range.

| Table 1.1: Examples of Blood Parameters and Their Set Points | |

|---|---|

| Osmolarity of Blood | 295-310 mOsM |

| pH of Blood | 7.35-7.45 |

| Arterial PCO₂ | 35-46 mmHg |

| Arterial PO₂ | 80-100 mmHg |

| Glucose (fasting) | 70-100 mg/dL |

| Sodium (Na⁺) | 135-145 mM |

| Potassium (K⁺) | 3-5 mM |

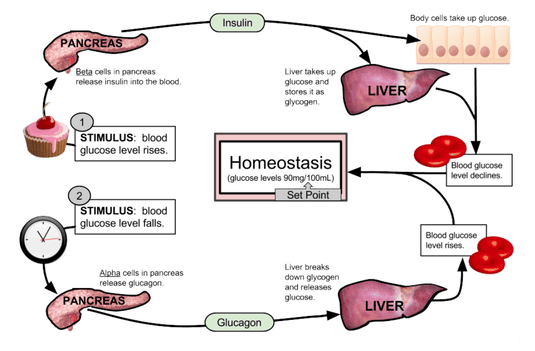

Example: Blood Glucose Regulation (Between Meals)

A person’s blood glucose (parameter) has a normal range (set point) of 70 to 100 mg/dL. If a person has not eaten in a while, their blood glucose decreases. If it goes below 70 mg/dL, the person will have hypoglycemia (low blood sugar). This decrease is the stimulus.

This decrease is detected by receptors in the pancreas, which responds by releasing the hormone glucagon into the bloodstream. Glucagon travels to the liver and stimulates hepatocytes (liver cells) to break down their glycogen stores and release glucose molecules into the blood. This increases blood glucose levels, opposing the original stimulus. Once glucose is restored to its normal range, the signal for glucagon release dissipates. This "off switch" is a key element of negative feedback.

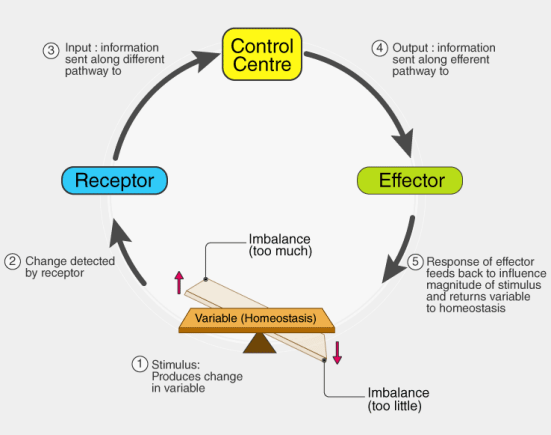

The Nitty Gritty of the Feedback Loop

To describe feedback loops with consistent terms, we can identify seven general components that create the loop.

Homeostatic Control Mechanisms (The "Feedback Loops")

To maintain homeostasis, the body uses control systems, most of which involve feedback loops. These loops constantly monitor conditions, detect changes, and initiate responses to bring variables back to their set point.

Every feedback loop has three basic components:

1. Receptor (Sensor)

Function: Monitors the environment and responds to changes (stimuli). It detects the deviation from the set point.

Action: Sends information (input) along an afferent pathway (e.g., nerve impulses) to the control center.

Example: Thermoreceptors in the skin and hypothalamus detect changes in body temperature.

2. Control Center (Integrator)

Function: Receives and analyzes the input from the receptor. It compares the input to the set point (the ideal value) and determines the appropriate response.

Action: Sends commands (output) along an efferent pathway (e.g., nerve impulses, hormones) to the effector.

Example: The hypothalamus in the brain acts as the body's thermostat, comparing current body temperature to the set point of ~37°C (98.6°F).

3. Effector

Function: Carries out the control center's response. It provides the means for the control center's output to affect the stimulus.

Action: Its action either reduces the stimulus (negative feedback) or enhances it (positive feedback).

Example: Sweat glands, blood vessels in the skin, and skeletal muscles (shivering) are effectors that help regulate body temperature.

The Communication Pathway

RECEPTOR

Afferent Pathway

CONTROL CENTER

Efferent Pathway

EFFECTOR

Types of Feedback Loops

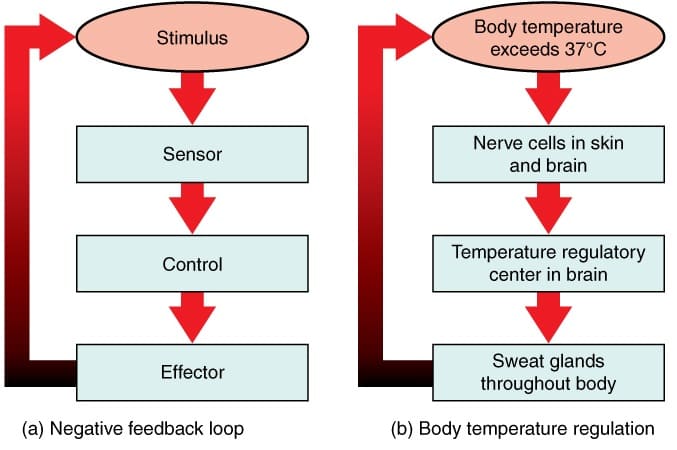

Negative Feedback Loops

(Most Common and Essential for Homeostasis)

Mechanism: The output of the system shuts off or reduces the intensity of the original stimulus, bringing the variable back toward the set point. It works to counteract the change.

Goal: To prevent severe changes and maintain stability.

Analogy: A thermostat controlling a furnace. When the temperature drops, the furnace turns on. Once the temperature reaches the set point, the furnace turns off (negative feedback).

Specific Example: Increased Body Temperature

If a person has been digging in the garden on a hot day, their body temperature rises above its set point of about 98.6°F. This is the stimulus. Thermoreceptors in the skin detect this change and send afferent information to the hypothalamus (the integration center). The hypothalamus then sends efferent signals to the effector tissues: sweat glands and cutaneous blood vessels. The response is diaphoresis (sweating) and cutaneous vasodilation (widening of blood vessels in the skin). Evaporation of sweat and increased blood flow to the skin dissipate heat, causing body temperature to decrease back to its set point.

Other Physiological Examples:

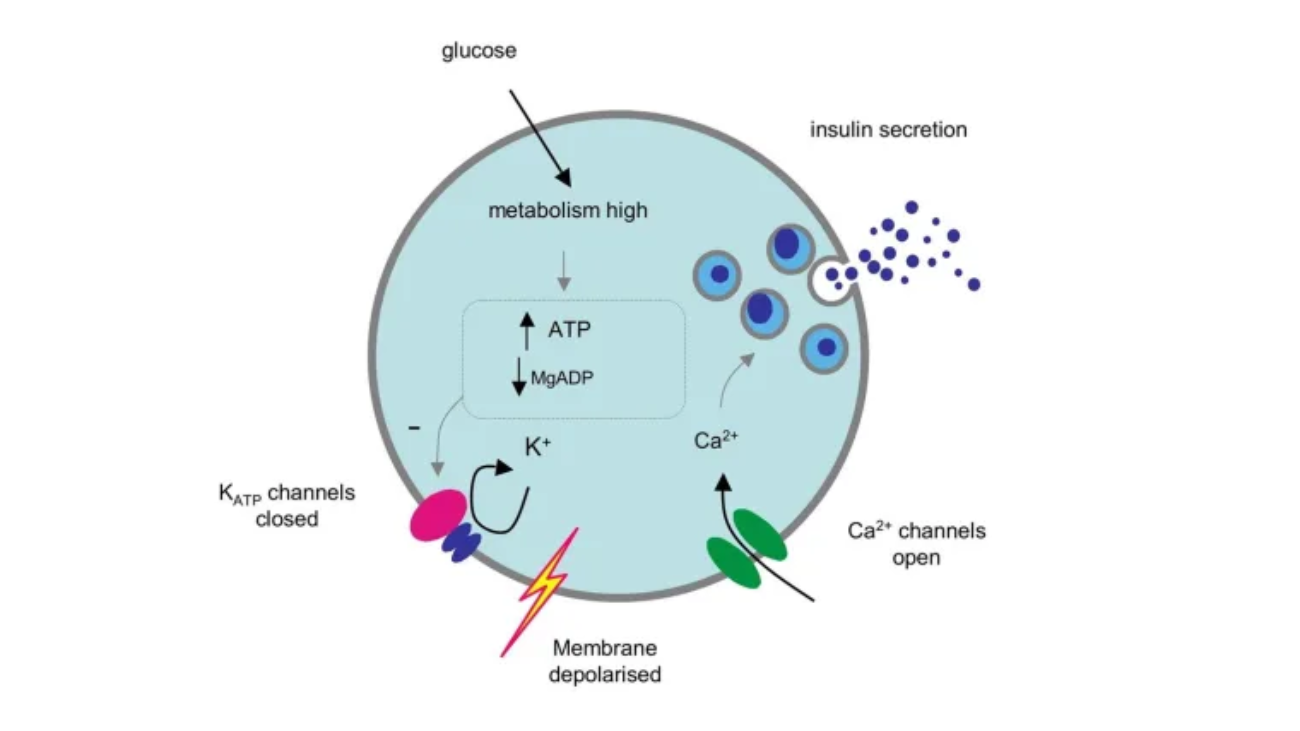

- Blood Glucose Regulation: After a meal, high blood glucose stimulates the pancreas to release insulin. Insulin causes cells to take up glucose, lowering blood glucose levels.

- Blood Pressure Regulation: Baroreceptors detect high blood pressure, signal the brain, which then slows heart rate and dilates blood vessels to lower pressure.

Positive Feedback Loops

(Rare, but Important for Specific Events)

Mechanism: The output of the system enhances or exaggerates the original stimulus, driving the variable further away from the initial set point. This is often part of a process that needs to be completed quickly.

Goal: To amplify a process until a specific event is completed.

Analogy: A microphone picking up sound, which is amplified and fed back into the microphone, creating a loop of increasing volume.

Specific Example: Childbirth

When a baby is ready to be born, its head pushes down upon the cervix, increasing pressure. This stretch (the stimulus) is detected by mechanoreceptors, which send an afferent signal to the brain. The brain (integration center) signals the posterior pituitary to release the hormone oxytocin. Oxytocin (efferent pathway) travels in the blood to the uterus (effector tissue), causing its smooth muscle to contract more forcefully. This pushes the baby’s head harder against the cervix, intensifying the original stimulus and triggering more oxytocin release. This cycle repeats, with contractions becoming stronger and more frequent, until the baby is born, which breaks the loop.

Other Physiological Examples:

- Blood Clotting: Platelets at an injury site release chemicals that attract more platelets, rapidly forming a plug.

- Generation of an Action Potential: An initial depolarization opens some Na⁺ channels, causing more Na⁺ to enter, which opens even more Na⁺ channels, leading to a rapid, all-or-nothing spike.

Diseases from Homeostatic Imbalance

The failure of homeostatic control mechanisms to maintain the body's stable internal environment leads directly to disease. Here are several examples:

Diabetes Mellitus

Imbalance: Chronic hyperglycemia (high blood glucose).

Mechanism: Insufficient insulin production (Type 1) or cellular resistance to insulin's effects (Type 2).

Consequences: Widespread damage to blood vessels, leading to heart attack, stroke, kidney failure, blindness, and nerve damage.

Hypo- and Hyperthyroidism

Imbalance: Disruption of thyroid hormone levels, which regulate metabolism.

Mechanism: Underproduction (Hypothyroidism) or overproduction (Hyperthyroidism) of thyroid hormones.

Consequences: Hypothyroidism leads to slowed metabolism, weight gain, and fatigue. Hyperthyroidism leads to accelerated metabolism, weight loss, anxiety, and rapid heart rate.

Kidney Failure (Renal Failure)

Imbalance: Inability to regulate fluid volume, electrolytes, pH, and excrete metabolic wastes.

Consequences: Fluid overload (edema), fatal cardiac arrhythmias from high potassium (hyperkalemia), toxic accumulation of urea (uremia), and dangerous drops in blood pH (acidosis).

Hypertension (High Blood Pressure)

Imbalance: Chronic elevation of systemic arterial blood pressure.

Mechanism: Multifactorial, often involving dysfunction in the nervous or endocrine systems' regulatory mechanisms (e.g., renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system).

Consequences: Increased risk of heart attack, stroke, kidney disease, and heart failure.

Dehydration and Overhydration

Imbalance: Disruption of fluid and electrolyte balance.

Consequences: Dehydration leads to low blood volume and pressure. Overhydration can dilute electrolytes (especially sodium), leading to brain cell swelling, seizures, and death (hyponatremia).

Sepsis

Imbalance: A life-threatening, dysregulated systemic response to infection.

Mechanism: The body's own immune response becomes overactive, leading to widespread inflammation and organ damage.

Consequences: Septic shock, multi-organ failure, and death.

Summary of Homeostasis

| Concept | Description |

|---|---|

| Definition | Maintenance of a relatively stable internal environment (dynamic equilibrium). |

| Importance | Essential for cell survival, optimal enzyme function, and overall health. |

| Control Loop Components | Receptor (detects change), Control Center (determines response), Effector (carries out response). |

| Negative Feedback | Most common. Output reduces/counteracts the original stimulus to restore the set point. Goal is stability. (e.g., Temperature, Blood Glucose). |

| Positive Feedback | Rare. Output enhances/exaggerates the original stimulus to complete an event. Goal is amplification. (e.g., Childbirth, Blood Clotting). |

| Homeostatic Imbalance | Occurs when control mechanisms fail, leading to disease. |

Test Your Knowledge

A quiz on the principles of Homeostasis.

1. Which of the following best defines homeostasis?

- The process of responding to external stimuli.

- The body's ability to maintain a relatively stable internal environment despite external changes.

- The process by which an organism grows and develops.

- The irreversible cessation of bodily functions.

Correct (b): This is the classic and most accurate definition of homeostasis. It emphasizes the "relatively stable" nature, acknowledging minor fluctuations.

Incorrect (a): Responding to stimuli is a broader biological characteristic, not exclusively homeostasis.

Incorrect (c): Growth and development are separate biological processes.

Incorrect (d): This describes death, the opposite of maintaining life.

2. A shivering response to cold, which raises body temperature, is an example of what feedback mechanism?

- Positive feedback

- Negative feedback

- Feedforward control

- Adaptation

Correct (b): The shivering response reverses the initial change (cold temperature) by generating heat. This counteraction is the hallmark of negative feedback.

Incorrect (a): Positive feedback would amplify the cold, making the body colder.

Incorrect (c): Feedforward control anticipates changes before they happen.

Incorrect (d): Adaptation refers to long-term adjustments, not acute responses.

3. Which component of a feedback loop detects changes in a regulated variable?

- Effector

- Control center

- Receptor (sensor)

- Set point

Correct (c): Receptors are specialized structures that detect changes (stimuli) in the environment.

Incorrect (a): The effector carries out the response.

Incorrect (b): The control center processes information.

Incorrect (d): The set point is the desired value, not a detection component.

4. In a negative feedback loop, the response of the effector:

- Amplifies the original stimulus.

- Counteracts or reverses the original stimulus.

- Has no effect on the original stimulus.

- Creates a new stimulus.

Correct (b): The defining characteristic of negative feedback is that the system's response works against the initial change to bring the variable back to its set point.

Incorrect (a): This describes positive feedback.

5. Childbirth labor contractions, which amplify in a cycle, are an example of what type of feedback?

- Negative feedback

- Positive feedback

- Homeostatic imbalance

- Allosteric regulation

Correct (b): The contractions stimulate more oxytocin, which causes even stronger contractions, creating a self-amplifying cycle. This amplification is characteristic of positive feedback.

Incorrect (a): Negative feedback would reduce contractions.

6. The "set point" in a homeostatic control system refers to the:

- Actual value of the variable at any given moment.

- Desired or ideal value around which the variable is maintained.

- Range within which the variable is allowed to fluctuate.

- Output generated by the effector.

Correct (b): The set point is the reference value for a regulated variable (e.g., 37°C for body temperature).

Incorrect (a): The actual value fluctuates around the set point.

Incorrect (c): This describes the "normal range" or "dynamic equilibrium."

7. Which of the following is typically regulated by negative feedback loops to maintain homeostasis?

- Blood clotting

- Blood glucose levels

- Ovulation

- Action potential generation

Correct (b): Blood glucose is tightly regulated by insulin and glucagon in a negative feedback loop.

Incorrect (a, c, d): Blood clotting, ovulation, and action potentials are all examples of processes involving positive feedback.

8. When homeostatic mechanisms are overwhelmed or fail, what condition can result?

- Adaptation

- Positive feedback

- Homeostatic imbalance

- Physiological resilience

Correct (c): When homeostatic mechanisms fail, the body enters a state of homeostatic imbalance, which can lead to disease.

9. What is the primary role of the control center in a homeostatic feedback loop?

- To carry out the response.

- To detect the stimulus.

- To receive input, compare it to the set point, and send commands.

- To amplify the deviation from the set point.

Correct (c): The control center (e.g., the brain) is the integration point that processes information and determines the response.

Incorrect (a): This is the role of the effector.

Incorrect (b): This is the role of the receptor.

10. A change in the external environment that causes a deviation from the set point is called a:

- Response

- Effector

- Stimulus

- Feedback

Correct (c): A stimulus is any detectable change in the internal or external environment that can initiate a response.

11. Which statement about positive feedback loops is generally TRUE?

- They are more common than negative feedback loops.

- They amplify the initial stimulus to complete a specific event.

- They work to bring a variable back to its set point.

- They are primarily involved in regulating body temperature.

Correct (b): Positive feedback loops are characterized by amplification, driving a process to a swift conclusion, such as childbirth or blood clotting.

Incorrect (a): Negative feedback is far more common for daily regulation.

Incorrect (c): Bringing a variable back to its set point is negative feedback.

12. The range of normal values around a set point is often referred to as:

- Set point itself

- Dynamic equilibrium

- Control limit

- Regulatory threshold

Correct (b): Homeostasis maintains a "dynamic equilibrium" because variables constantly fluctuate slightly around the set point, not held rigidly at a single value.

13. Maintaining internal body temperature within a narrow range is an example of:

- Allostasis

- Positive feedback

- Homeostasis

- Non-equilibrium thermodynamics

Correct (c): Maintaining a stable internal temperature is a classic example of homeostatic regulation.

Incorrect (a): Allostasis refers to achieving stability through change, a more complex adaptive process.

Incorrect (b): Positive feedback would lead to runaway heating or cooling.

14. Which body system is NOT considered a major regulator of homeostatic functions?

- Nervous system

- Endocrine system

- Integumentary system

- Respiratory system

Correct (c): While the skin (integumentary system) is a crucial effector in temperature regulation, it is not a primary regulatory system with control centers like the nervous and endocrine systems.

15. If blood pressure drops, the response of increased heart rate is primarily initiated by the:

- Effector

- Control center

- Stimulus

- Receptor

Correct (b): Receptors detect the drop, send info to the control center (brain), which then sends commands to the effectors (heart, vessels) to initiate the response.

16. A system that maintains a dynamic constancy of internal conditions is said to be in _________.

17. In a feedback loop, the component that receives commands and produces a change is the _________.

18. A negative feedback mechanism will act to _________ a deviation from the set point.

19. The regulation of blood glucose by insulin and glucagon is a classic example of a _________ feedback loop.

20. A physiological state where conditions fluctuate within a narrow, healthy range is known as _________.

Quiz Complete!

Your Score:

0%

0 / 0 correct

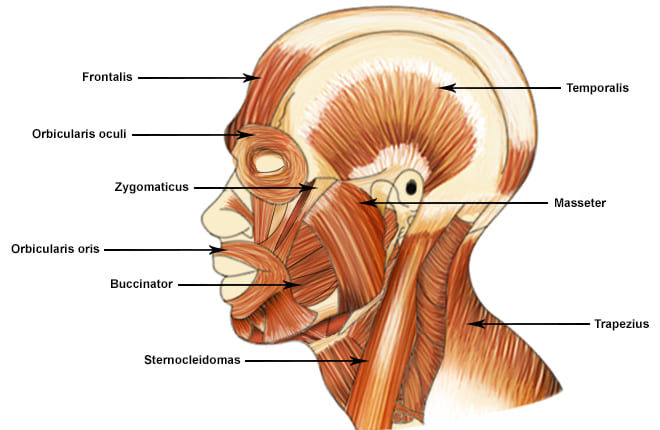

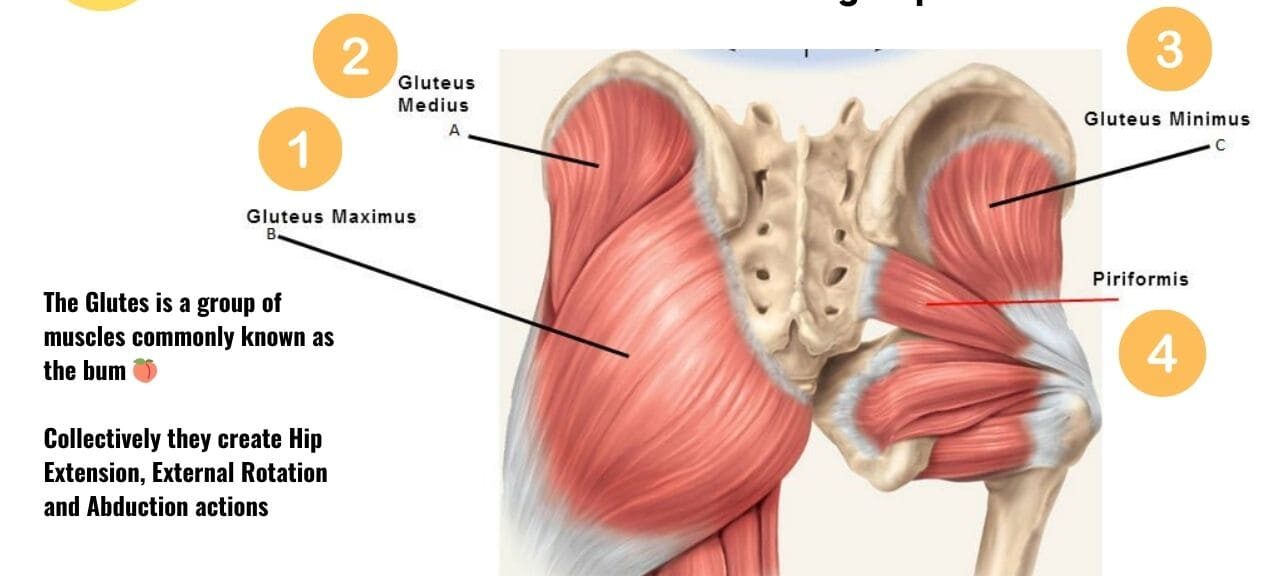

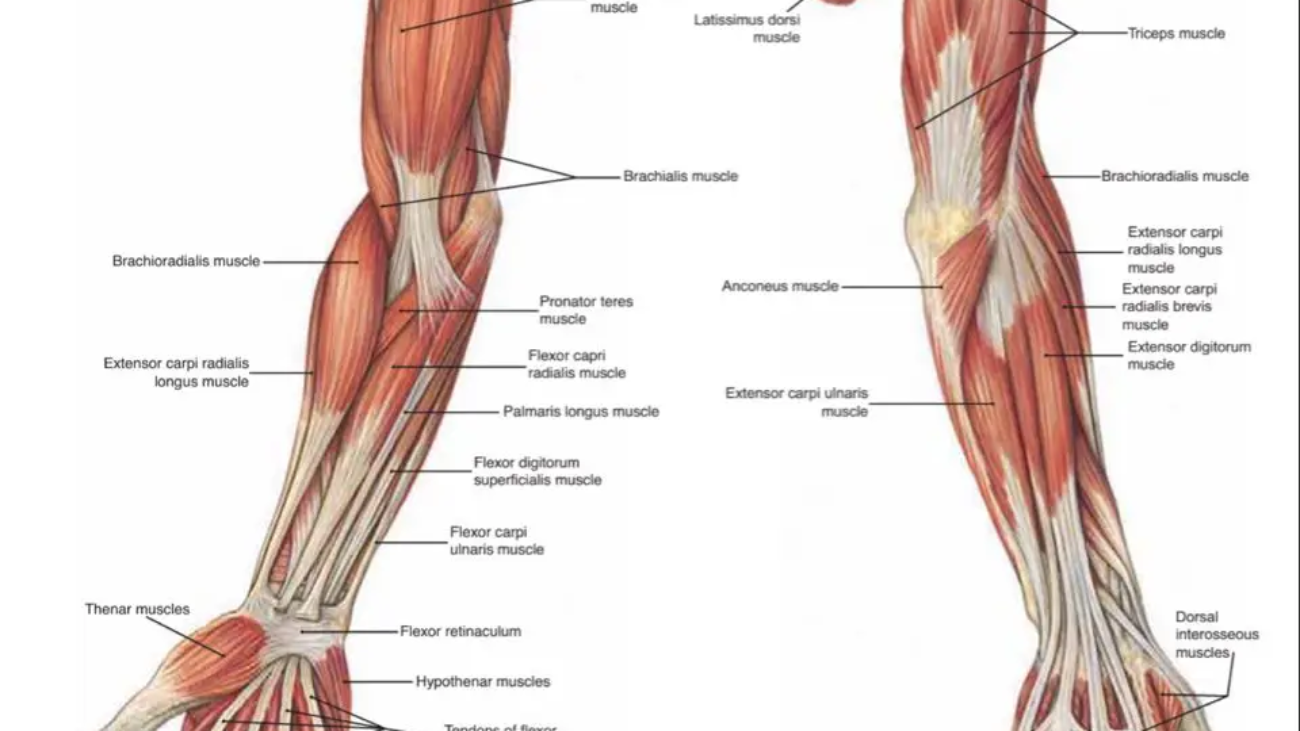

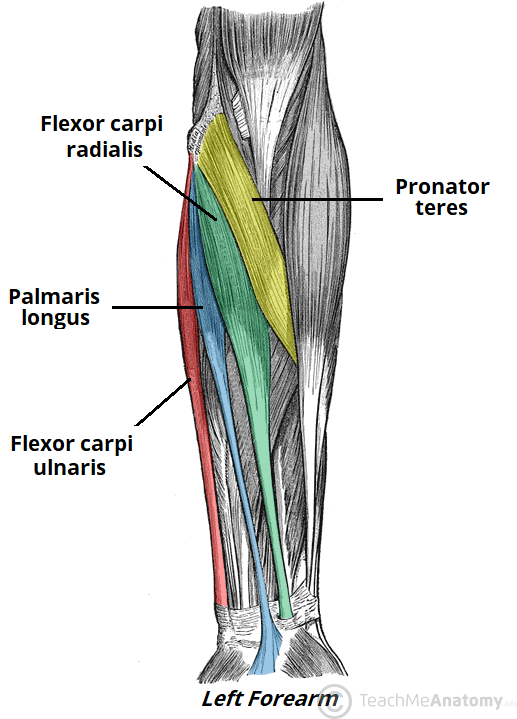

Superficial Layer

Superficial Layer