Axial Skeleton Muscles: The Footress.

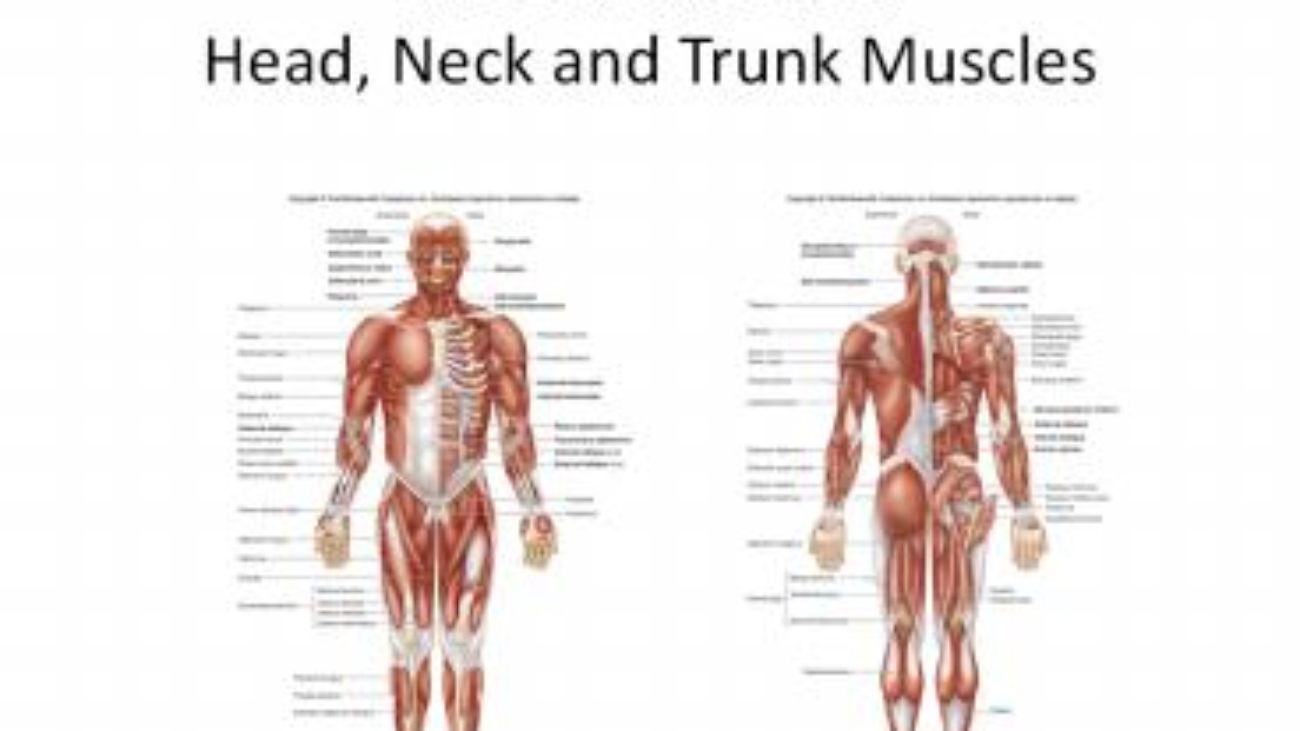

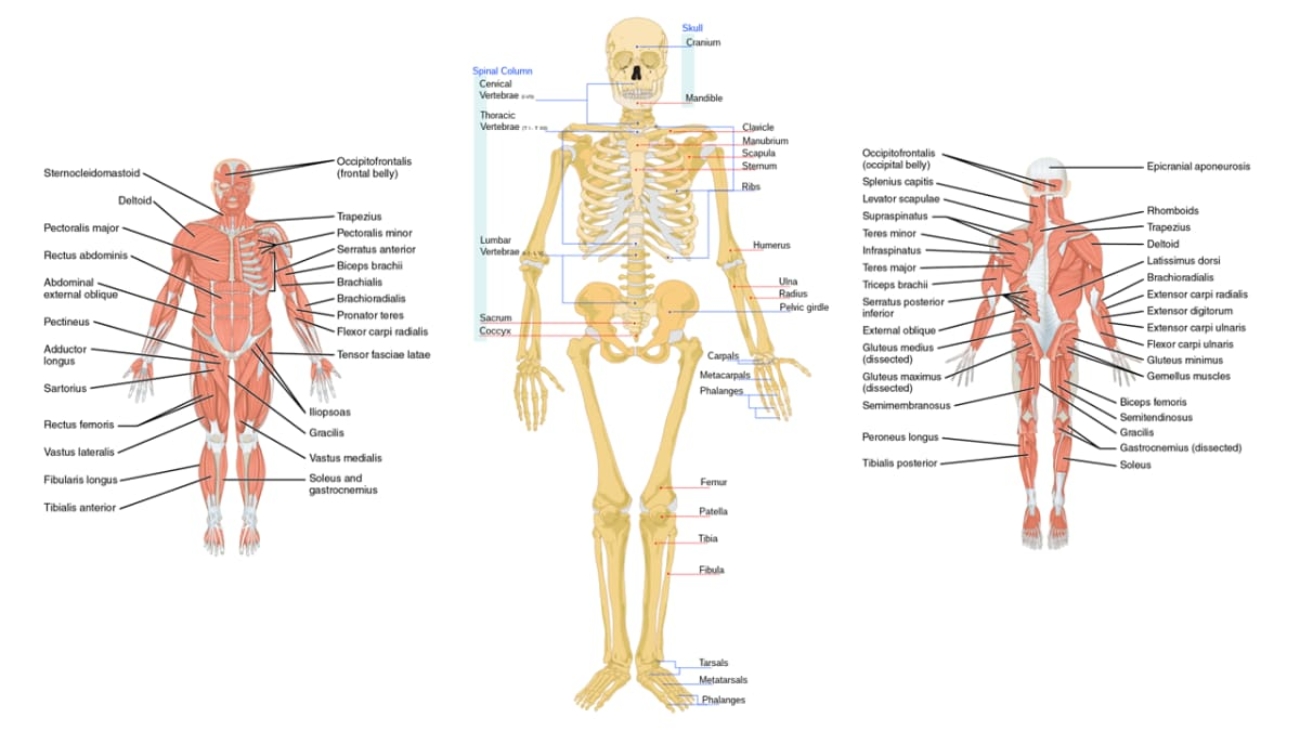

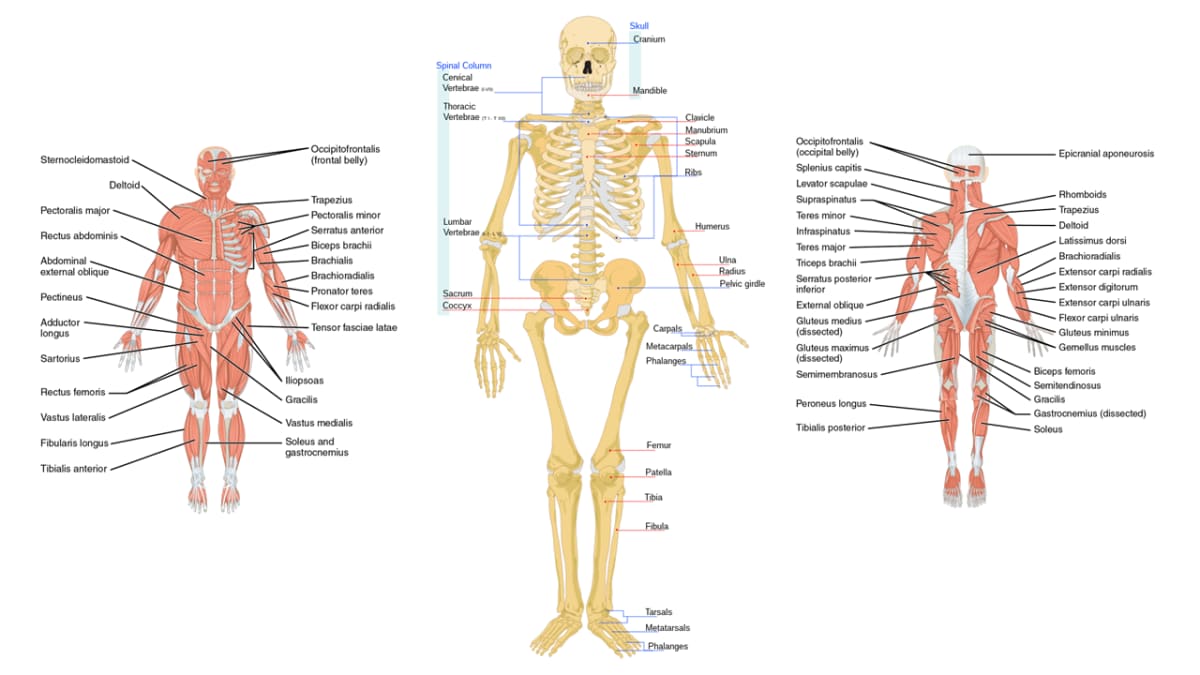

Muscles of the Axial Skeleton

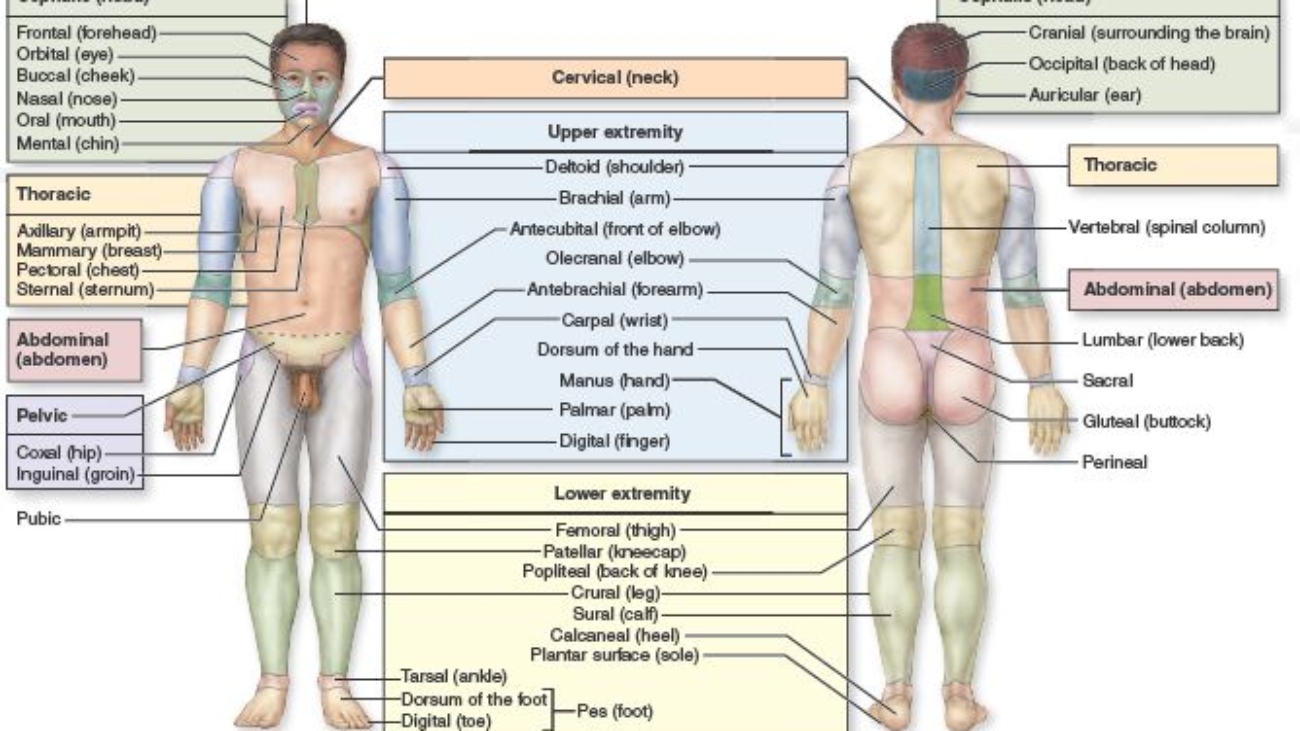

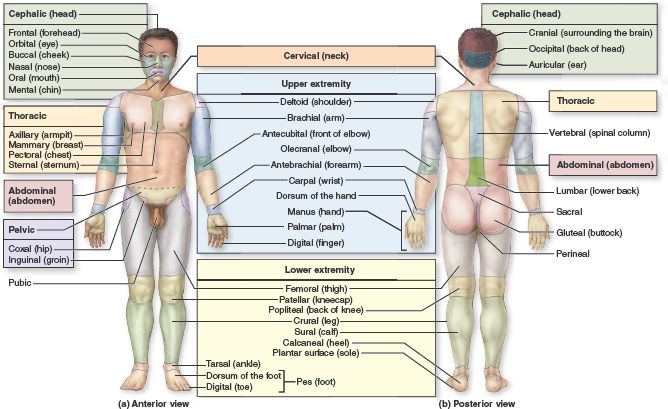

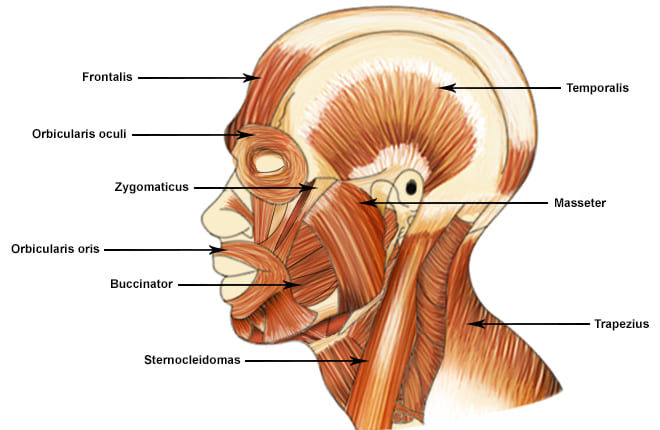

A. Muscles of the Head and Face

The muscles of the head can be broadly categorized into muscles of facial expression and muscles of mastication (chewing).

1. Muscles of Facial Expression

These unique muscles insert into the skin or other muscles, allowing us to show a wide range of emotions. They are all innervated by the Facial Nerve (Cranial Nerve VII).

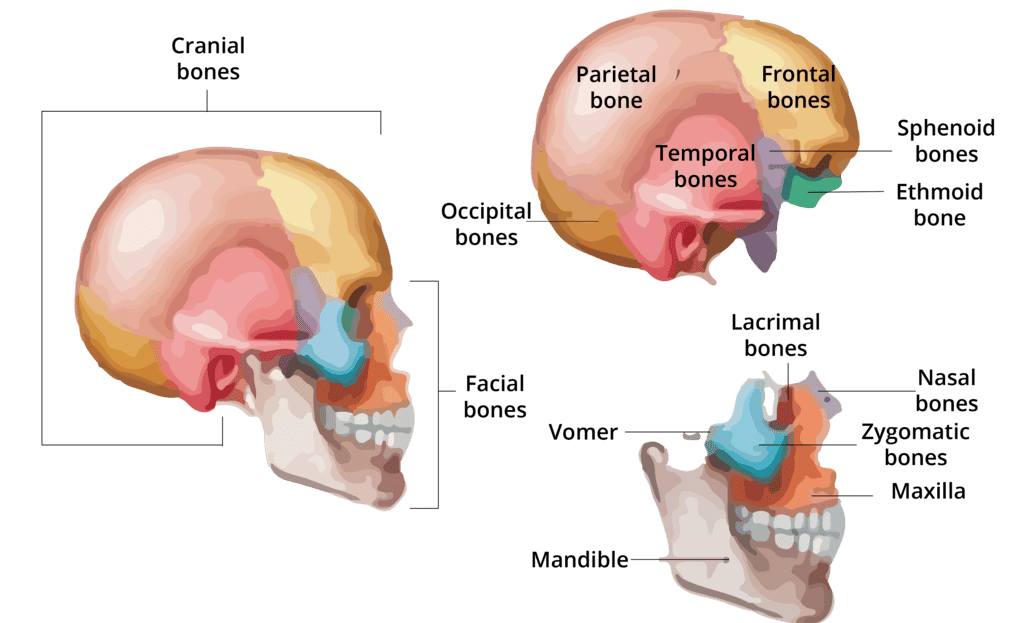

a. Occipitofrontalis (Epicranius)

A broad muscle covering the top of the skull with two bellies. The Frontal belly raises the eyebrows and wrinkles the forehead, while the Occipital belly pulls the scalp posteriorly.

b. Orbicularis Oculi

A ring-like muscle encircling the eye. Its primary action is to close the eye (blinking, winking) and squint.

c. Orbicularis Oris

A complex muscle encircling the mouth. It closes and protrudes the lips, as in puckering or kissing.

d. Zygomaticus Major and Minor

Extend from the cheekbone to the corner of the mouth. They are the primary "smiling" muscles, raising the lateral corners of the mouth upward.

e. Buccinator

A thin, flat muscle of the cheek. It compresses the cheek for whistling or sucking and holds food between the teeth during chewing.

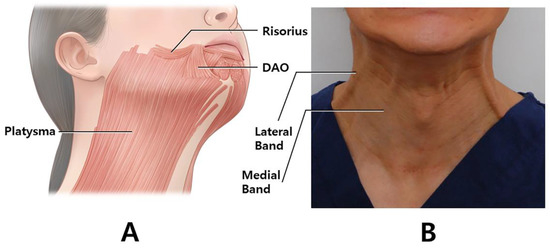

f. Platysma

A broad, superficial sheet of muscle in the neck. It tenses the skin of the neck, depresses the mandible, and pulls the lower lip down.

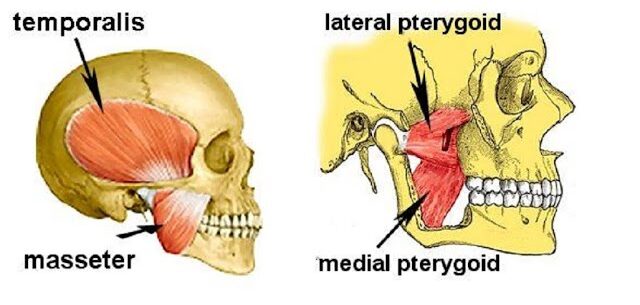

2. Muscles of Mastication (Chewing)

These four pairs of muscles are responsible for moving the mandible for chewing. They are all innervated by the Mandibular division of the Trigeminal Nerve (Cranial Nerve V3).

a. Masseter

A powerful muscle on the side of the jaw. It is the primary elevator of the mandible (closes the jaw).

b. Temporalis

A fan-shaped muscle in the temporal fossa. It elevates and retracts the mandible.

c. Medial Pterygoid

Located deep to the mandible. It elevates the jaw and assists in side-to-side grinding movements.

d. Lateral Pterygoid

Located deep in the jaw. It protracts the mandible (pulls it forward), moves it side-to-side, and is the only muscle of mastication that helps open the jaw.

Summary Table of Head & Face Muscles

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| FACIAL EXPRESSION (CN VII) | |||

| Occipitofrontalis | Galea aponeurotica (Frontal); Occipital bone (Occipital) | Skin of eyebrows; Galea aponeurotica | Raises eyebrows, wrinkles forehead, pulls scalp |

| Orbicularis Oculi | Frontal and maxillary bones | Tissue of eyelid | Closes eye, squints, blinks |

| Orbicularis Oris | Maxilla and mandible | Skin and muscle at angles of mouth | Closes and protrudes lips (puckering) |

| Zygomaticus Major/Minor | Zygomatic bone | Skin and muscle at angle of mouth | Raises lateral corners of mouth (smiling) |

| Buccinator | Molar region of maxilla and mandible | Orbicularis oris | Compresses cheek (whistling, sucking) |

| Platysma | Fascia of chest | Base of mandible; skin at corner of mouth | Tenses skin of neck, depresses mandible |

| MASTICATION (CN V3) | |||

| Masseter | Zygomatic arch | Angle and ramus of mandible | Elevates mandible (closes jaw) |

| Temporalis | Temporal fossa | Coronoid process of mandible | Elevates and retracts mandible |

| Medial Pterygoid | Sphenoid and palatine bones | Medial surface of ramus of mandible | Elevates mandible, moves side-to-side |

| Lateral Pterygoid | Sphenoid bone | Condylar process of mandible; TMJ capsule | Protracts and depresses (opens) jaw |

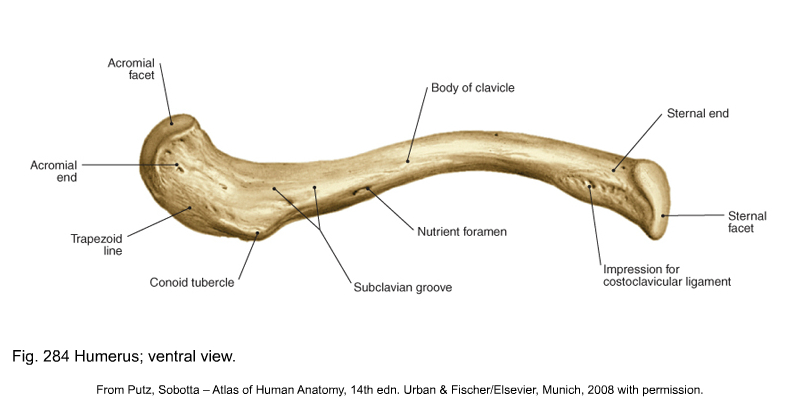

B. Muscles of the Neck

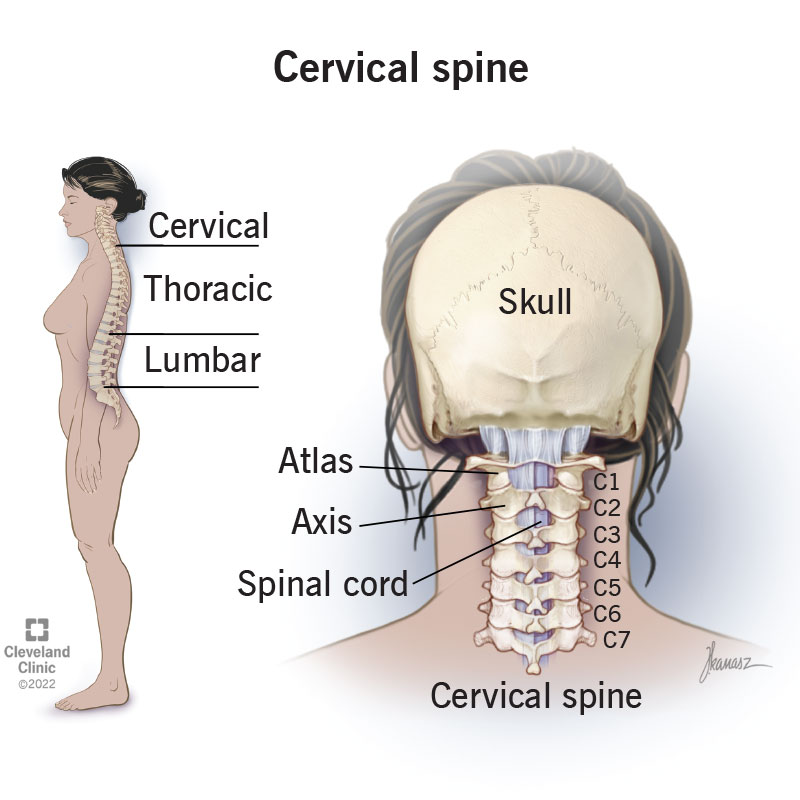

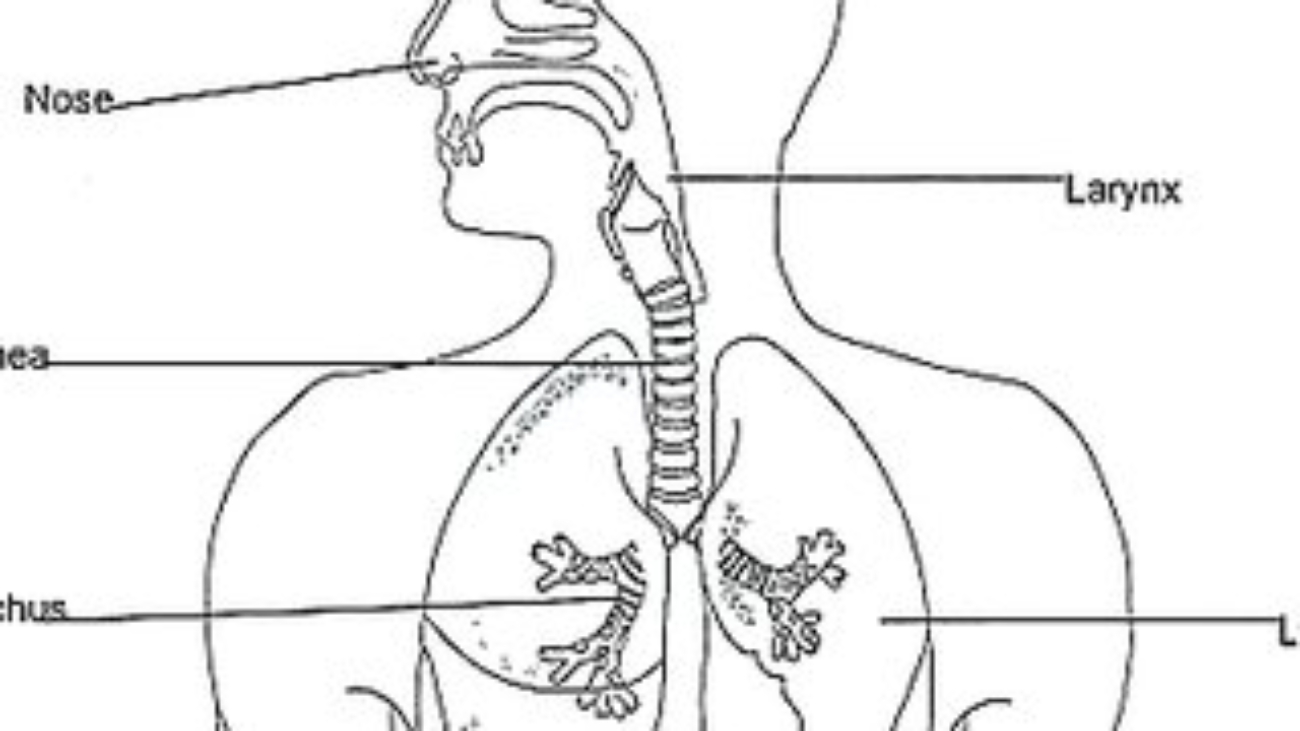

The muscles of the neck are diverse, responsible for moving the head, stabilizing the cervical spine, assisting in breathing, and facilitating swallowing and speech. They are categorized here based on location and primary actions.

1. Superficial Anterior Neck Muscles

a. Sternocleidomastoid (SCM)

A large, two-headed muscle on each side of the neck. When acting alone (unilaterally), it rotates the head to the opposite side and flexes it to the same side. When both act together (bilaterally), they flex the neck (chin to chest).

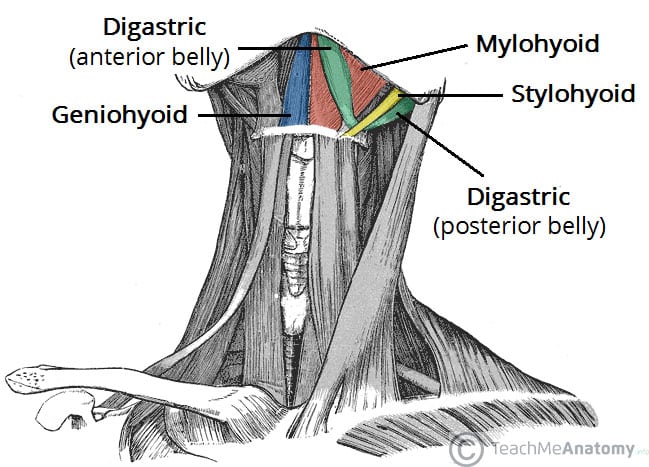

2. Suprahyoid Muscles (Above the Hyoid Bone)

These muscles form the floor of the mouth and are primarily responsible for elevating the hyoid bone during swallowing and speaking.

a. Digastric

Two-bellied muscle that elevates the hyoid or depresses the mandible (opens the mouth).

b. Mylohyoid

Forms the floor of the mouth; elevates hyoid and floor of mouth.

c. Geniohyoid

Elevates and protracts the hyoid bone.

d. Stylohyoid

Elevates and retracts the hyoid bone.

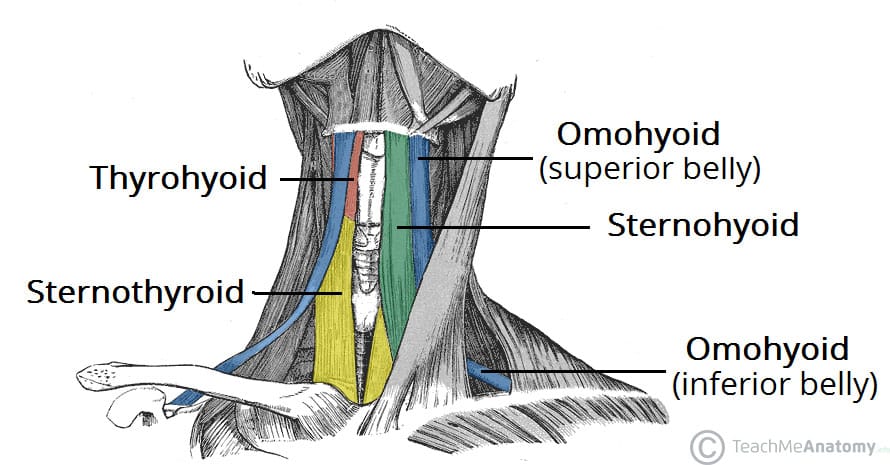

3. Infrahyoid Muscles (Strap Muscles - Below the Hyoid)

These "strap-like" muscles primarily depress the hyoid bone and larynx during swallowing and speaking.

a. Sternohyoid

Depresses the hyoid bone and larynx.

b. Omohyoid

Two-bellied muscle that depresses and retracts the hyoid.

c. Sternothyroid

Depresses the larynx and hyoid bone.

d. Thyrohyoid

Depresses the hyoid bone but elevates the larynx.

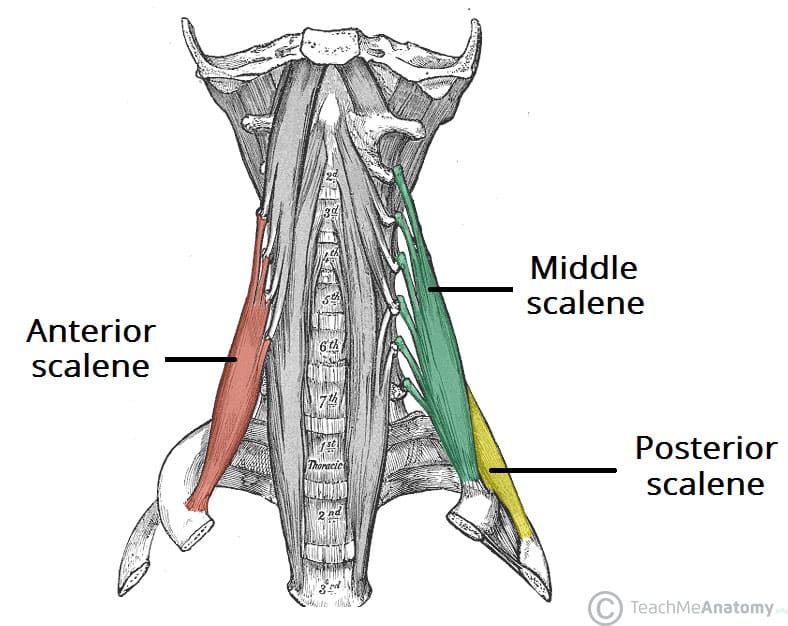

4. Deep Lateral Neck Muscles (Scalenes)

The Anterior, Middle, and Posterior Scalene muscles are important for lateral flexion of the neck. They also act as accessory muscles of inspiration by elevating the first two ribs.

Summary Table of Neck Muscles

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sternocleidomastoid | Manubrium & Clavicle | Mastoid process | CN XI, C2-C3 | Unilateral: Rotates head opp., flexes same side. Bilateral: Flexes neck. |

| Digastric | Mandible & Mastoid process | Hyoid bone | CN V3 & CN VII | Elevates hyoid, depresses mandible. |

| Mylohyoid | Mandible | Hyoid bone | CN V3 | Elevates hyoid & floor of mouth. |

| Sternohyoid | Manubrium & Clavicle | Hyoid bone | Ansa cervicalis | Depresses hyoid and larynx. |

| Omohyoid | Scapula | Hyoid bone | Ansa cervicalis | Depresses and retracts hyoid. |

| Sternothyroid | Manubrium | Thyroid cartilage | Ansa cervicalis | Depresses larynx and hyoid. |

| Thyrohyoid | Thyroid cartilage | Hyoid bone | C1 via CN XII | Depresses hyoid, elevates larynx. |

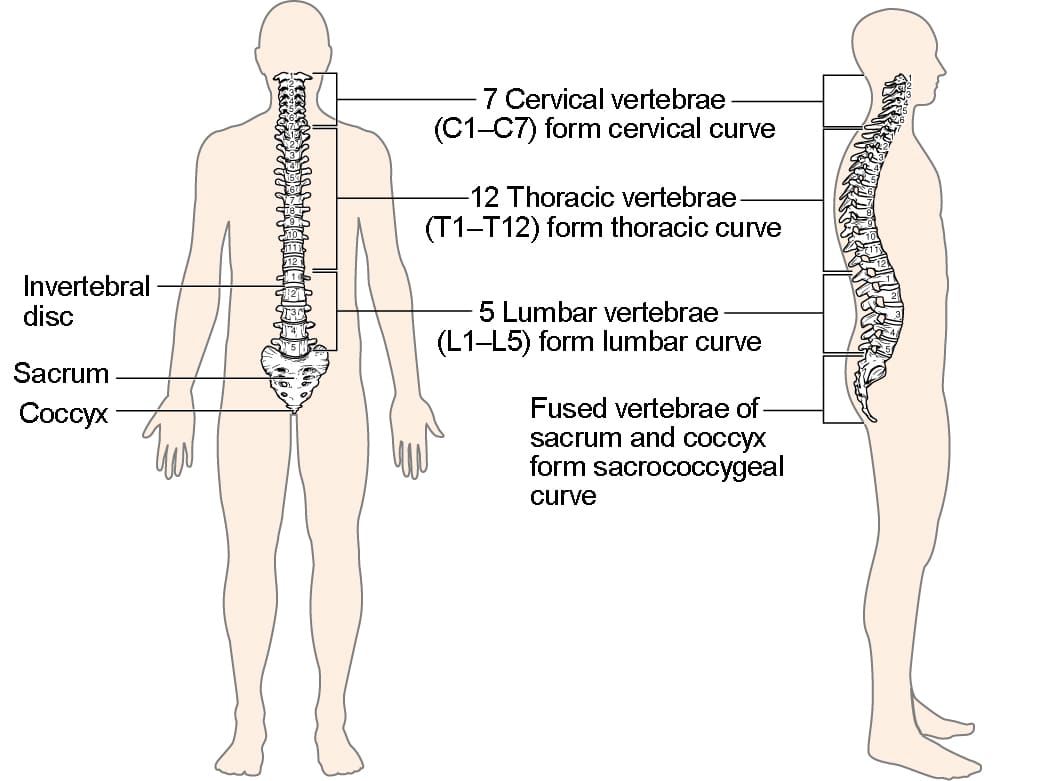

| Scalenes (Ant, Mid, Post) | Cervical vertebrae (C2-C7) | First & Second ribs | Cervical spinal nerves | Flexes neck, elevates ribs for inspiration. |

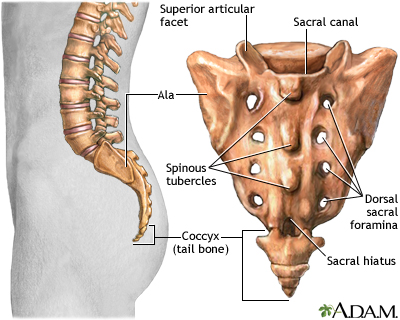

C. Muscles of the Torso (Trunk)

The muscles of the trunk are vital for maintaining posture, protecting internal organs, facilitating respiration, and enabling a wide range of movements.

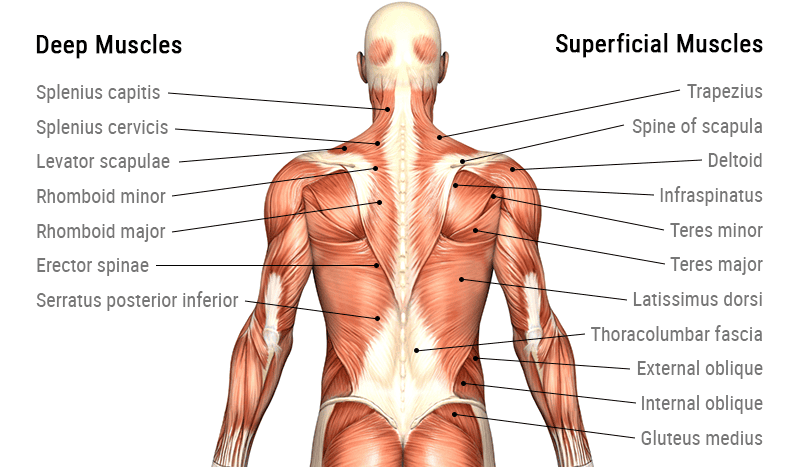

1. Muscles of the Back

These complex, layered muscles move and stabilize the vertebral column, head, and shoulders.

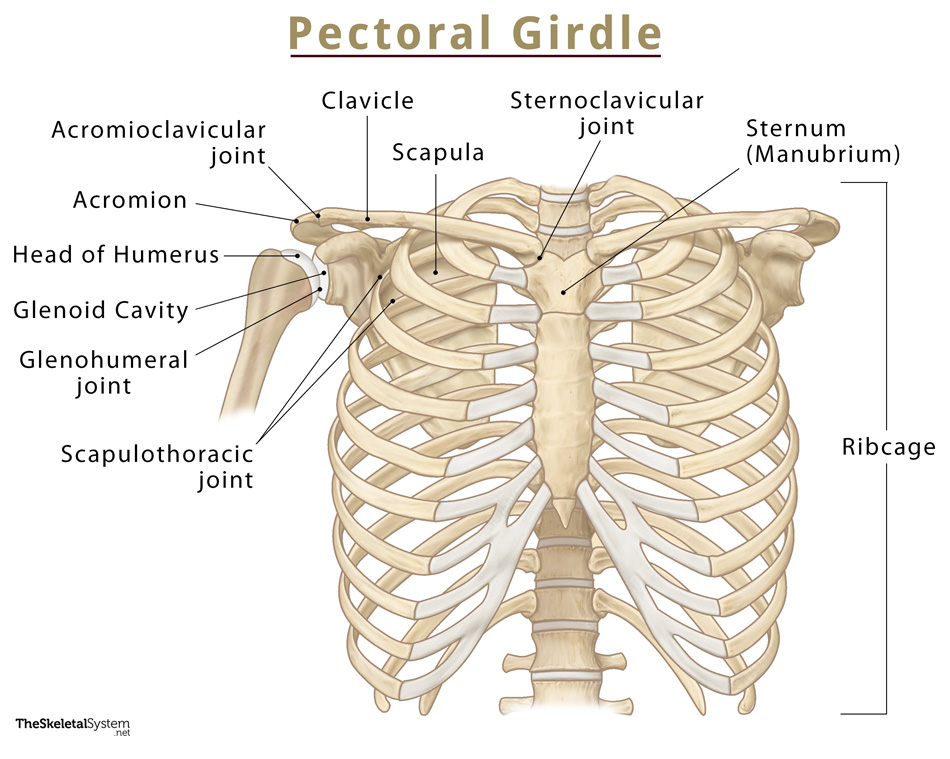

a. Superficial Back Muscles

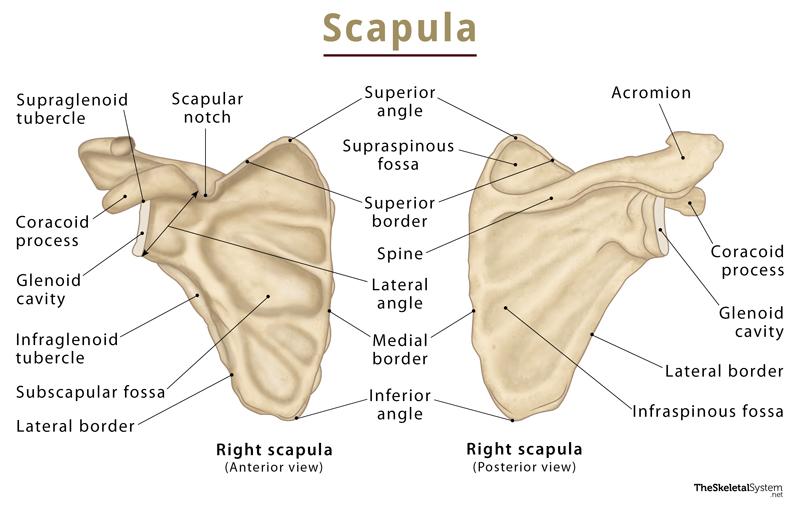

Primarily act on the upper limbs. Includes the large Trapezius (moves scapula), Latissimus Dorsi (extends and adducts arm), and the deeper Rhomboids and Levator Scapulae (retract and elevate scapula).

b. Intermediate Back Muscles

Respiratory muscles. The Serratus Posterior Superior elevates ribs for inspiration, while the Serratus Posterior Inferior depresses ribs for expiration.

c. Deep (Intrinsic) Back Muscles

Responsible for posture and vertebral column movement. The main group is the massive Erector Spinae (Iliocostalis, Longissimus, Spinalis), the prime mover of back extension. Deeper still is the Transversospinalis group, which stabilizes vertebrae.

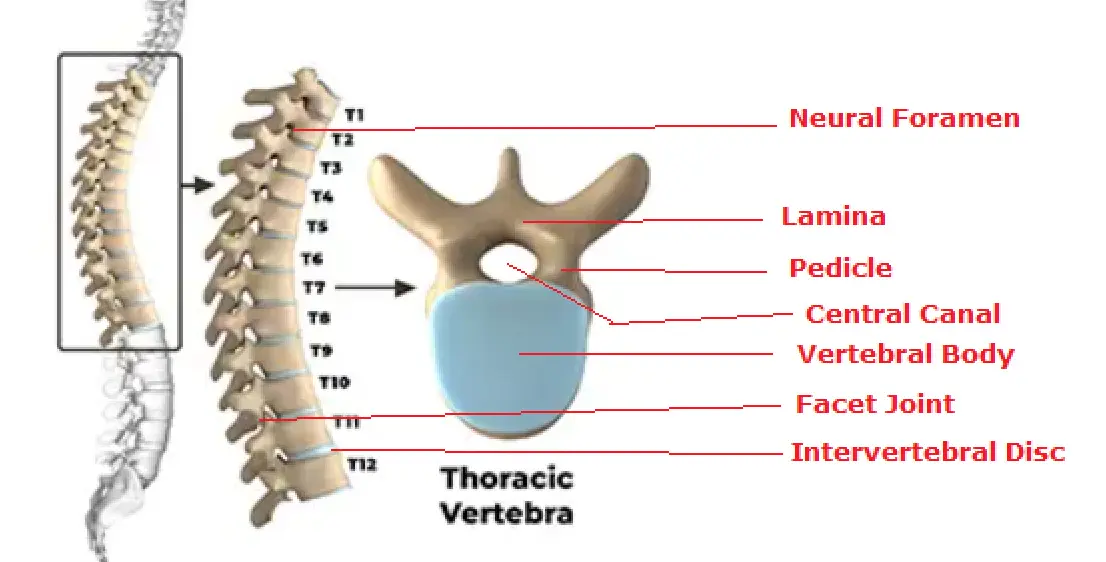

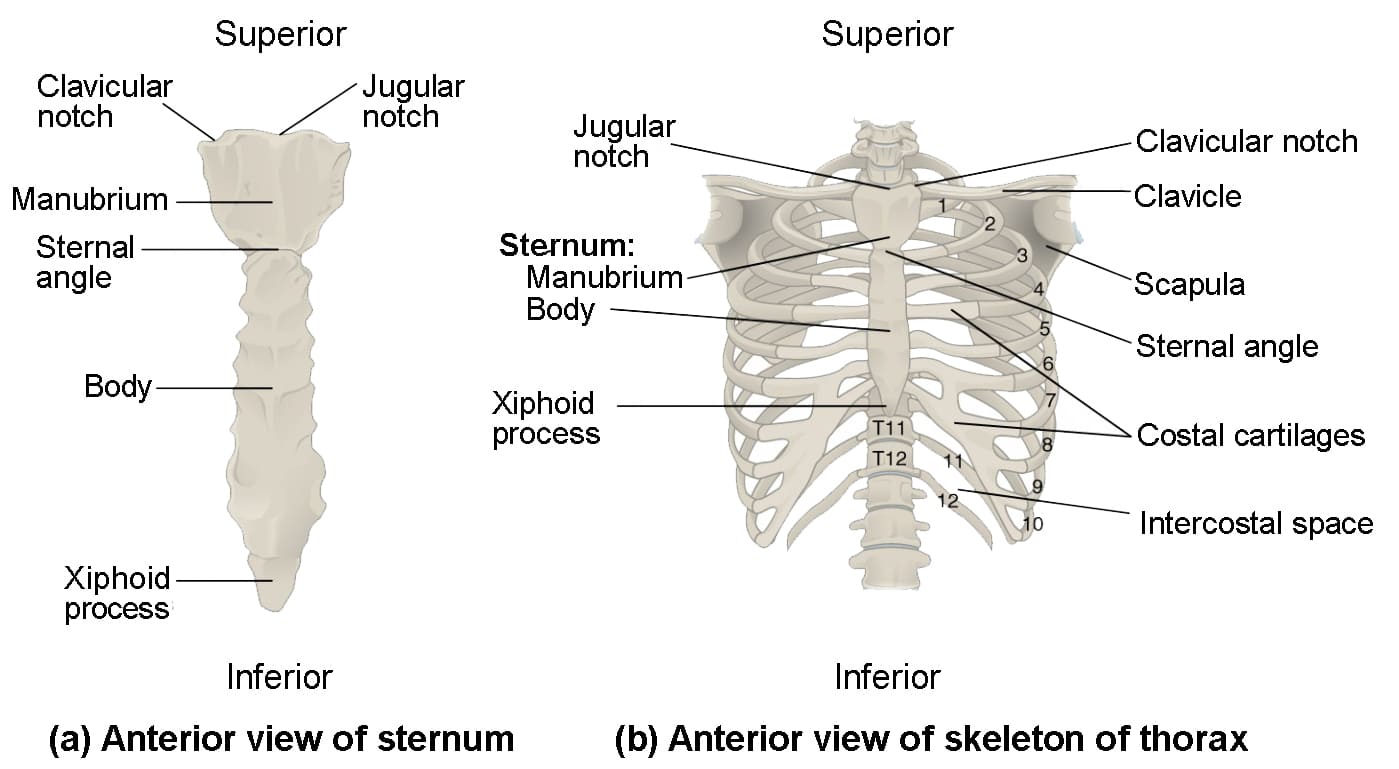

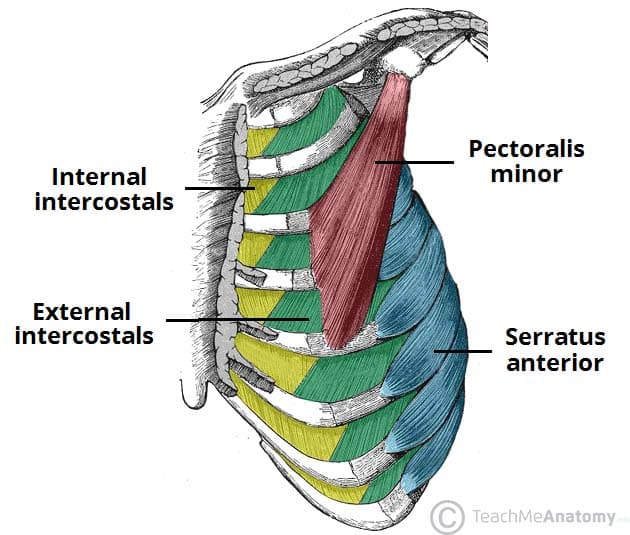

2. Muscles of the Thorax (Chest Wall)

These muscles are primarily involved in the mechanics of breathing.

a. Intercostal Muscles

The External Intercostals elevate the ribs for inspiration. The Internal and Innermost Intercostals depress the ribs for forced expiration.

b. Diaphragm

The primary muscle of respiration. This large, dome-shaped muscle separates the thoracic and abdominal cavities. It contracts and flattens to increase thoracic volume, causing inspiration.

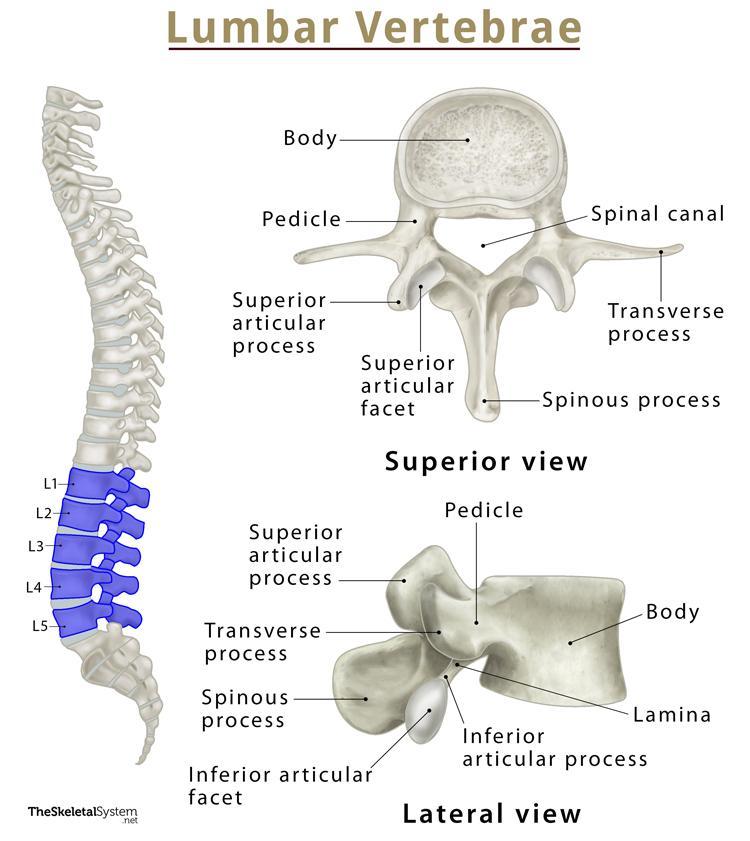

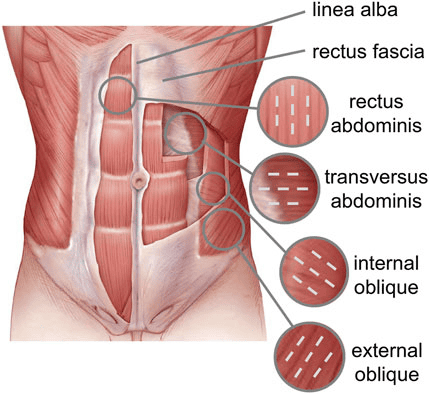

3. Muscles of the Abdominal Wall

Form a strong, flexible wall that protects viscera, moves the trunk, and compresses the abdominal cavity.

a. Rectus Abdominis

The vertical "six-pack" muscle, segmented by tendinous intersections. It is the primary flexor of the vertebral column (as in sit-ups).

b. Obliques & Transversus Abdominis

Three layers of flat muscles that wrap the abdomen. The External Oblique (fibers run down and in), Internal Oblique (fibers run up and in), and the deepest Transversus Abdominis (fibers run horizontally). They work together to rotate and flex the trunk and compress the abdominal contents.

c. Quadratus Lumborum

A deep, square-shaped muscle of the posterior abdominal wall that laterally flexes the trunk.

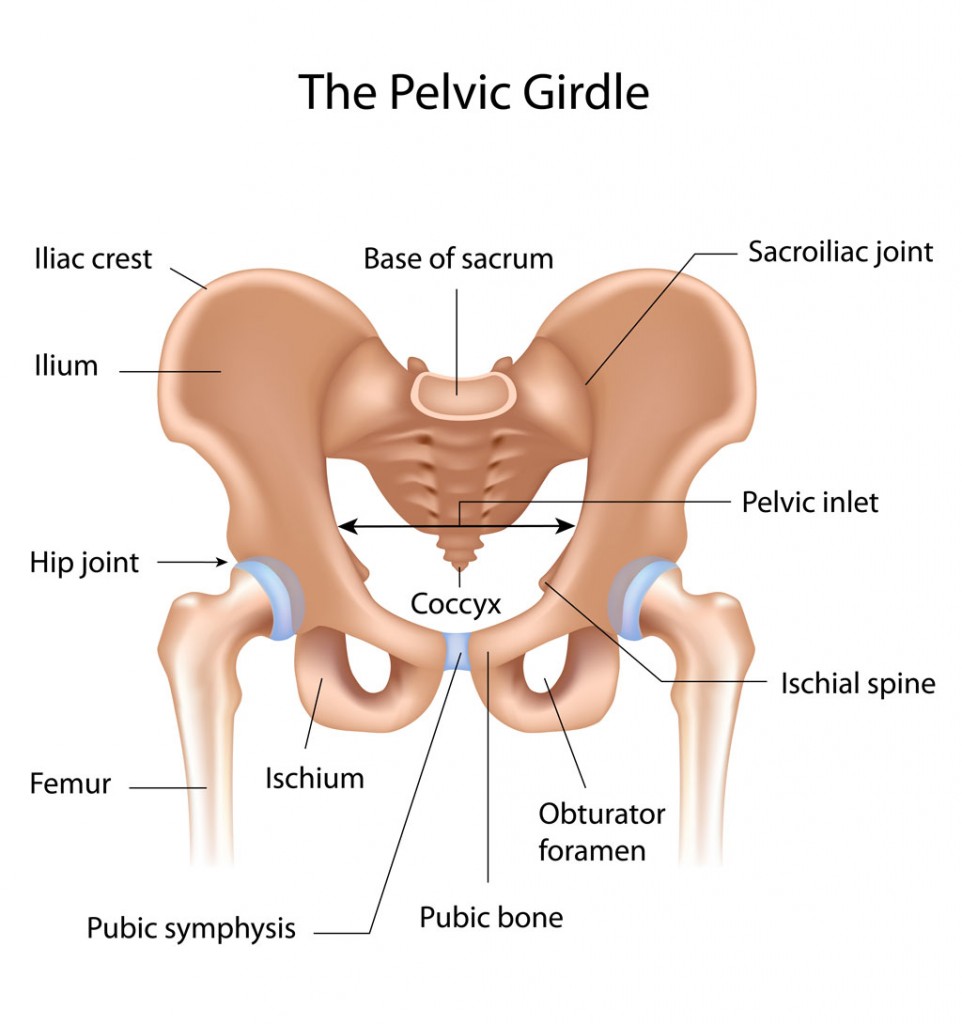

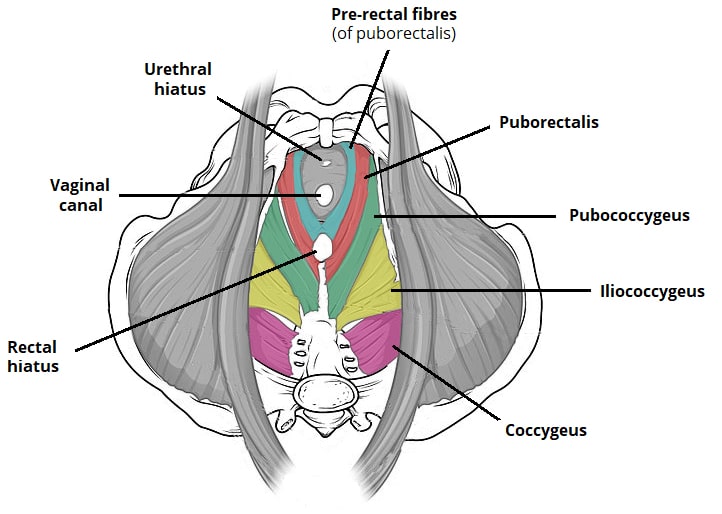

4. Pelvic Floor Muscles (Pelvic Diaphragm)

Close the inferior outlet of the pelvis, supporting pelvic organs and controlling continence.

a. Levator Ani Group & Coccygeus

This broad, funnel-shaped muscle group forms the major part of the pelvic floor, supporting pelvic organs and resisting increases in intra-abdominal pressure.

Summary Table of Torso Muscles

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Main Actions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRAPEZIUS | Occipital bone, C7-T12 spinous processes | Clavicle, acromion, spine of scapula | Spinal Accessory (CN XI), C3-C4 | Elevates, retracts, depresses, rotates scapula |

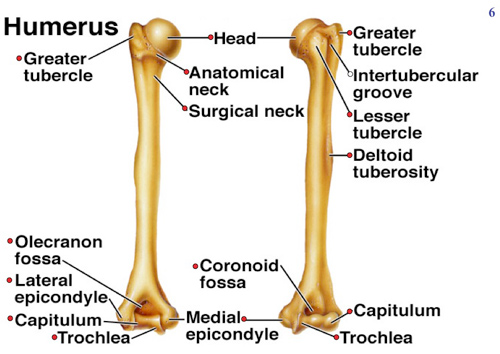

| LATISSIMUS DORSI | T7-L5 spinous processes, iliac crest | Intertubercular groove of humerus | Thoracodorsal Nerve (C6-C8) | Extends, adducts, medially rotates arm |

| ERECTOR SPINAE GROUP | Iliac crest, sacrum, vertebrae | Ribs, vertebrae, mastoid process | Dorsal rami of spinal nerves | Extend & laterally flex vertebral column |

| EXTERNAL INTERCOSTALS | Rib above | Rib below | Intercostal nerves (T1-T11) | Elevate ribs (inspiration) |

| INTERNAL INTERCOSTALS | Rib above | Rib below | Intercostal nerves (T1-T11) | Depress ribs (forced expiration) |

| DIAPHRAGM | Xiphoid, costal cartilages, lumbar vertebrae | Central tendon | Phrenic Nerves (C3-C5) | Primary muscle of inspiration |

| RECTUS ABDOMINIS | Pubic crest and symphysis | Xiphoid process, costal cartilages 5-7 | Intercostal nerves (T7-T12) | Flexes vertebral column, compresses abdomen |

| EXTERNAL OBLIQUE | Ribs 5-12 | Linea alba, pubic tubercle, iliac crest | Intercostal nerves (T7-T12) | Flexes & rotates trunk (opposite side) |

| INTERNAL OBLIQUE | Thoracolumbar fascia, iliac crest | Linea alba, pubic crest, ribs 10-12 | Intercostal (T7-T12), Iliohypo/inguinal (L1) | Flexes & rotates trunk (same side) |

| TRANSVERSUS ABDOMINIS | Thoracolumbar fascia, iliac crest, ribs 7-12 | Linea alba, pubic crest | Intercostal (T7-T12), Iliohypo/inguinal (L1) | Compresses abdominal contents |

| QUADRATUS LUMBORUM | Iliac crest | Last rib, transverse processes of L1-L4 | Lumbar Plexus (T12-L4) | Laterally flexes vertebral column |

| LEVATOR ANI GROUP | Pubis, ischial spine | Coccyx, walls of pelvic organs | Pudendal Nerve (S2-S4), S3-S4 | Supports pelvic organs, maintains continence |

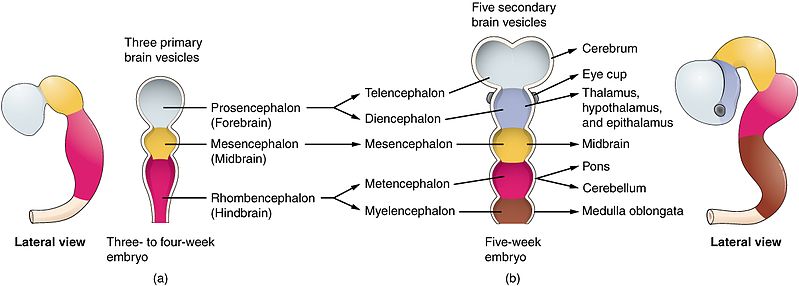

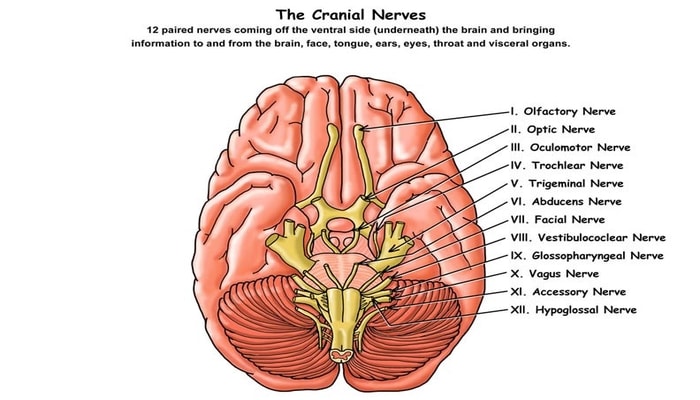

Reference: The 12 Cranial Nerves

The cranial nerves are a set of 12 paired nerves that arise directly from the brain and brainstem, as opposed to spinal nerves which emerge from the spinal cord. They are responsible for conveying sensory and motor information to and from the head and neck region, as well as controlling visceral functions.

Mnemonics for Memorization

For Nerve Names:

"Oh Oh Oh To Touch And Feel A Girls Vagina Ah Heaven"

For Functional Type (S=Sensory, M=Motor, B=Both):

"Some Say Marry Money, But My Brother Says Big Brains Matter More"

I. Olfactory Nerve

Function: Special sense of smell.

Clinical Test: Ask patient to identify common scents (e.g., coffee, vanilla) with each nostril closed.

II. Optic Nerve

Function: Special sense of vision.

Clinical Test: Test visual acuity (Snellen chart) and visual fields.

III. Oculomotor Nerve

Function: Controls most eye movements (up, down, medially), raises eyelid, and constricts pupil.

Clinical Test: Test eye movements (H-pattern); check for pupillary light reflex and eyelid drooping (ptosis).

IV. Trochlear Nerve

Function: Controls the superior oblique muscle, which moves the eye downward and inward.

Clinical Test: Ask patient to look down and in; damage can cause vertical double vision.

V. Trigeminal Nerve

Function: Sensory for the face (touch, pain, temperature) and Motor for muscles of mastication (chewing).

Clinical Test: Test facial sensation with a cotton wisp; ask patient to clench jaw and palpate masseter and temporalis muscles.

VI. Abducens Nerve

Function: Controls the lateral rectus muscle, which moves the eye laterally (abducts the eye).

Clinical Test: Ask patient to look to the side; damage can cause inability to look laterally and horizontal double vision.

VII. Facial Nerve

Function: Motor for muscles of facial expression, and Sensory for taste from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

Clinical Test: Ask patient to smile, frown, puff cheeks, and raise eyebrows. Damage causes facial paralysis (Bell's Palsy).

VIII. Vestibulocochlear Nerve

Function: Special senses of hearing (cochlear part) and balance/equilibrium (vestibular part).

Clinical Test: Test hearing (whisper test, Rinne/Weber tests); check for balance issues and vertigo.

IX. Glossopharyngeal Nerve

Function: Motor for swallowing, and Sensory for taste from the posterior one-third of the tongue and sensation from the pharynx.

Clinical Test: Check gag reflex; ask patient to say "ahhh" and watch for symmetrical uvula elevation.

X. Vagus Nerve

Function: The "wanderer"; provides parasympathetic motor innervation to most thoracic and abdominal viscera. Also motor to pharynx/larynx and sensory from the viscera.

Clinical Test: Check gag reflex and ability to swallow; assess for hoarseness.

XI. Accessory Nerve

Function: Controls the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles.

Clinical Test: Ask patient to shrug shoulders (trapezius) and turn head against resistance (SCM).

XII. Hypoglossal Nerve

Function: Controls the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the tongue.

Clinical Test: Ask patient to stick out their tongue; it will deviate towards the side of the lesion.

Test Your Knowledge

Check your understanding of the Muscles of the Head, Neck & Trunk.

1. Which muscle is primarily responsible for retracting the scapula and is located deep to the trapezius?

- Latissimus Dorsi

- Levator Scapulae

- Rhomboid Major

- Serratus Posterior Superior

Correct (c): The Rhomboid Major, along with the Rhomboid Minor, lies deep to the Trapezius and pulls the scapula towards the spine (retraction).

Incorrect (a): Latissimus Dorsi primarily acts on the humerus (arm extension, adduction, medial rotation).

Incorrect (b): Levator Scapulae elevates and rotates the scapula downward, not primarily retraction.

Incorrect (d): Serratus Posterior Superior assists in inspiration by elevating ribs, not a primary scapular retractor.

2. A patient presents with difficulty closing their right eye and drooping of the right side of their mouth. Which cranial nerve is most likely affected?

- Trigeminal Nerve (CN V)

- Facial Nerve (CN VII)

- Hypoglossal Nerve (CN XII)

- Spinal Accessory Nerve (CN XI)

Correct (b): The Facial Nerve (CN VII) innervates the muscles of facial expression. Difficulty closing the eye (Orbicularis Oculi) and mouth drooping (Orbicularis Oris) are classic signs of Facial Nerve palsy.

Incorrect (a): Trigeminal Nerve (CN V) innervates muscles of mastication (chewing), not facial expression.

Incorrect (c): Hypoglossal Nerve (CN XII) innervates tongue muscles.

Incorrect (d): Spinal Accessory Nerve (CN XI) innervates the Sternocleidomastoid and Trapezius.

3. Which of the following muscles is not considered an infrahyoid muscle?

- Sternohyoid

- Omohyoid

- Digastric

- Thyrohyoid

Correct (c): The Digastric muscle is a suprahyoid muscle, located above the hyoid bone, and helps elevate the hyoid and depress the mandible.

Incorrect (a, b, d): Sternohyoid, Omohyoid, and Thyrohyoid are all infrahyoid (strap) muscles located below the hyoid bone, which primarily depress the hyoid.

4. During forced expiration, which abdominal muscle is most effective at compressing abdominal contents?

- Rectus Abdominis

- External Oblique

- Transversus Abdominis

- Quadratus Lumborum

Correct (c): The Transversus Abdominis, with its horizontally oriented fibers, is the deepest and most effective muscle for compressing the abdominal contents, which is crucial for forced expiration.

Incorrect (a): Rectus Abdominis primarily flexes the vertebral column.

Incorrect (b): External Oblique is involved in trunk rotation and flexion.

Incorrect (d): Quadratus Lumborum is primarily involved in lateral flexion of the trunk.

5. Unilateral contraction of the sternocleidomastoid muscle results in:

- Flexion of the neck and elevation of the sternum.

- Rotation of the head to the ipsilateral (same) side.

- Rotation of the head to the contralateral (opposite) side.

- Extension of the neck and depression of the scapula.

Correct (c): When one SCM contracts, it pulls the head down towards the same shoulder (lateral flexion) and rotates the head to face the opposite side.

Incorrect (a): Flexion of the neck is a bilateral action of the SCM.

Incorrect (b): It rotates the head to the opposite, not the same, side.

Incorrect (d): These are not primary actions of the SCM.

6. Which muscle is the prime mover for inspiration, increasing the vertical dimension of the thoracic cavity?

- External Intercostals

- Internal Intercostals

- Diaphragm

- Serratus Posterior Superior

Correct (c): The diaphragm is the primary muscle of quiet inspiration. Its contraction flattens it inferiorly, significantly increasing the thoracic cavity's vertical dimension.

Incorrect (a): External Intercostals assist inspiration by elevating the ribs.

Incorrect (b): Internal Intercostals are primarily involved in forced expiration.

Incorrect (d): Serratus Posterior Superior is an accessory muscle of inspiration.

7. The Erector Spinae group of muscles are primarily innervated by which of the following?

- Ventral rami of spinal nerves

- Dorsal rami of spinal nerves

- Phrenic nerve

- Thoracodorsal nerve

Correct (b): The deep intrinsic muscles of the back, including the Erector Spinae group, are characteristically innervated by the dorsal rami of the spinal nerves.

Incorrect (a): Ventral rami typically innervate muscles of the limbs and anterior/lateral trunk.

Incorrect (c): The Phrenic nerve innervates the diaphragm.

Incorrect (d): The Thoracodorsal nerve innervates the Latissimus Dorsi.

8. Which muscle is responsible for raising the eyebrows and wrinkling the forehead horizontally?

- Orbicularis Oculi

- Occipitalis

- Frontalis (Frontal belly of Occipitofrontalis)

- Zygomaticus Major

Correct (c): The Frontal belly of the Occipitofrontalis muscle is directly responsible for these actions of facial expression.

Incorrect (a): Orbicularis Oculi closes the eye.

Incorrect (b): Occipitalis pulls the scalp posteriorly.

Incorrect (d): Zygomaticus Major raises the corners of the mouth (smiling).

9. Damage to the Pudendal Nerve (S2-S4) would most directly impair the function of which muscle group?

- Erector Spinae

- Abdominal Obliques

- Levator Ani

- Scalenes

Correct (c): The Pudendal Nerve is the primary innervation for the muscles of the pelvic floor, including the Levator Ani group, which are critical for supporting pelvic organs and continence.

Incorrect (a): Erector Spinae are innervated by dorsal rami of spinal nerves.

Incorrect (b): Abdominal Obliques are innervated by intercostal nerves.

Incorrect (d): Scalenes are innervated by ventral rami of cervical spinal nerves.

10. The medial pterygoid muscle shares which primary action with the masseter and temporalis muscles?

- Depression of the mandible

- Protrusion of the mandible

- Elevation of the mandible

- Retraction of the mandible

Correct (c): The Masseter, Temporalis, and Medial Pterygoid are all primary muscles of mastication that work to elevate the mandible, thereby closing the jaw.

Incorrect (a): Depression of the mandible is primarily done by the Lateral Pterygoid and suprahyoid muscles.

Incorrect (b): Protrusion of the mandible is primarily done by the Lateral Pterygoid.

Incorrect (d): Retraction of the mandible is primarily done by the Temporalis.

11. The muscle that forms the floor of the mouth and is innervated by the mylohyoid nerve (branch of CN V3) is the _________.

12. The most superficial abdominal muscle with fibers running inferomedially is the __________.

13. The __________ muscle is a key muscle for side-bending the trunk and stabilizing the 12th rib.

14. The __________ muscle is unique for its dual innervation from both the Trigeminal (CN V3) and Facial (CN VII) nerves.

15. The primary muscle for closing and protruding the lips (the "kissing muscle") is the __________.

Quiz Complete!

Your Score:

0%

0 / 0 correct