Common Disorders of Tissues

Common Disorders of Tissues

Connective tissues are one of the four basic types of animal tissue (along with epithelial, muscle, and nervous tissues). They are the most abundant and widely distributed of the primary tissues, playing a crucial role in binding, supporting, and protecting organs, as well as storing energy and providing immunity. Unlike epithelial tissue, which is primarily composed of cells, connective tissue is characterized by its extracellular matrix (ECM).

Key Characteristics of Connective Tissues:

- Abundant Extracellular Matrix (ECM): This is the distinguishing feature. The ECM consists of two main components:

- Ground Substance: An amorphous gel-like material that fills the space between cells and fibers. It can be fluid, semi-fluid, gelatinous, or calcified. It contains water, proteoglycans, and glycoproteins.

- Protein Fibers: Provide strength and elasticity.

- Collagen fibers: Strongest and most abundant, providing high tensile strength (resistance to stretching).

- Elastic fibers: Composed of elastin, providing elasticity and recoil.

- Reticular fibers: Fine, branching collagenous fibers that form delicate networks, providing support in soft organs.

- Relatively Few Cells: Compared to epithelial tissue, connective tissues generally have fewer cells, which are often widely dispersed within the ECM.

- Vascularity: Most connective tissues are highly vascular (rich blood supply), though there are notable exceptions (e.g., cartilage is avascular, tendons and ligaments have limited vascularity).

- No Free Surface: Unlike epithelial tissue, connective tissue does not have a free surface exposed to the environment.

- Diverse Functions: Support, binding, protection, insulation, transport, and energy storage.

Major Types of Connective Tissues and Their Functions

Connective tissues are broadly categorized into several types, each with specialized functions and compositions of cells and ECM.

A. Loose Connective Tissue (Areolar, Adipose, Reticular)

These tissues have a relatively open, loose arrangement of fibers and a more abundant ground substance.

1. Areolar Connective Tissue

- Description: The most widely distributed connective tissue. It has a gel-like matrix with all three fiber types (collagen, elastic, reticular) loosely interwoven. Contains various cell types, including fibroblasts (most common), macrophages, mast cells, and some white blood cells.

- Location: Underlies epithelia; forms lamina propria of mucous membranes; packages organs; surrounds capillaries.

- Functions:

- Support and cushion: Provides flexible support.

- Fluid reservoir: Holds tissue fluid, acting as a "sponge."

- Immunity: Plays a role in inflammation due to its high cell diversity.

- Binding: Connects skin to underlying structures.

2. Adipose Tissue (Fat Tissue)

- Description: Primarily composed of adipocytes (fat cells), which store triglycerides. These cells are so large that they push the nucleus and cytoplasm to the periphery, giving them a "signet ring" appearance. Very little ECM.

- Location: Under skin (subcutaneous), around kidneys and eyeballs, within abdomen, breasts.

- Functions:

- Energy storage: Primary site for long-term energy reserves.

- Insulation: Reduces heat loss through the skin.

- Protection/Cushioning: Protects organs from mechanical shock.

- Endocrine function: Produces hormones like leptin.

3. Reticular Connective Tissue

- Description: Contains a delicate network of reticular fibers (a type of collagen) in a loose ground substance. Reticular cells (a type of fibroblast) are prominent.

- Location: Lymphoid organs (lymph nodes, spleen, bone marrow), liver.

- Functions:

- Structural support (Stroma): Forms a soft internal framework (stroma) that supports blood cells, lymphocytes, and other cell types in lymphoid organs.

B. Dense Connective Tissue

These tissues have a high density of collagen fibers, providing significant strength. There is less ground substance and fewer cells than loose connective tissue.

1. Dense Regular Connective Tissue

- Description: Primarily parallel collagen fibers, providing great tensile strength in one direction. Fibroblasts are the main cell type, squeezed between collagen bundles. Poorly vascularized.

- Location: Tendons (muscle to bone), ligaments (bone to bone), aponeuroses (sheet-like tendons).

- Functions:

- Strong attachment: Connects muscles to bones (tendons) and bones to bones (ligaments).

- Resists unidirectional pull: Withstands great tensile stress when pulling force is applied in one direction.

2. Dense Irregular Connective Tissue

- Description: Primarily irregularly arranged collagen fibers. Some elastic fibers and fibroblasts. Provides tensile strength in multiple directions.

- Location: Dermis of the skin, fibrous capsules of organs and joints, submucosa of digestive tract.

- Functions:

- Structural strength: Withstands tension exerted in many directions.

- Protection: Forms protective capsules around organs.

3. Elastic Connective Tissue

- Description: Predominantly elastic fibers, allowing for significant stretch and recoil. Also contains some collagen fibers and fibroblasts.

- Location: Walls of large arteries (aorta), bronchial tubes, vocal cords, ligaments associated with vertebral column (ligamentum nuchae).

- Functions:

- Elasticity: Allows recoil of tissue following stretching.

- Pulsatile flow: Maintains pulsatile flow of blood through arteries; aids passive recoil of lungs following inspiration.

C. Cartilage

1. Hyaline Cartilage

- Description: Most abundant type. Amorphous but firm matrix; imperceptible collagen fibers (type II); chondroblasts produce the matrix and, when mature, lie in lacunae as chondrocytes.

- Location: Covers the ends of long bones in joint cavities (articular cartilage), costal cartilage (ribs to sternum), nose, trachea, larynx.

- Functions: Support and cushioning: Supports and reinforces. Resilient cushioning: Has resilient properties. Reduces friction: Resists compressive stress at joints.

2. Elastic Cartilage

- Description: Similar to hyaline cartilage, but contains abundant elastic fibers in the matrix.

- Location: External ear (pinna), epiglottis.

- Functions: Flexibility and shape retention: Maintains the shape of a structure while allowing great flexibility.

3. Fibrocartilage

- Description: Matrix similar to hyaline cartilage but less firm, with thick collagen fibers (type I) predominant. Rows of chondrocytes alternating with thick collagen fibers.

- Location: Intervertebral discs, pubic symphysis, menisci of the knee.

- Functions: Tensile strength: Possesses tensile strength with the ability to absorb compressive shock. Shock absorption: Acts as a strong shock absorber.

D. Bone (Osseous Tissue)

A hard, rigid connective tissue. It is highly vascular and well-innervated. The hard matrix is primarily composed of collagen fibers and inorganic calcium salts (hydroxyapatite). Osteocytes (bone cells) reside in lacunae within the matrix.

- Description: Hard, calcified matrix containing many collagen fibers; osteocytes in lacunae. Very well vascularized.

- Functions: Support and protection, Leverage for movement (provides levers for muscles), Mineral storage (calcium, phosphorus), and Hematopoiesis (site of blood cell formation in red bone marrow).

E. Blood

Often considered a specialized connective tissue because it originates from mesenchyme and consists of cells (red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets) suspended in a fluid extracellular matrix (plasma).

- Description: Red and white blood cells in a fluid matrix (plasma).

- Functions: Transport (respiratory gases, nutrients, wastes, hormones), Regulation (body temperature, pH, fluid volume), and Protection (against blood loss and infection).

Summary of Primary Functions of Connective Tissues

- Binding and Support: Holding tissues and organs together (e.g., ligaments, tendons, areolar tissue).

- Protection: Physically protecting organs (e.g., bones, adipose tissue), and immunologically protecting the body (e.g., immune cells in areolar tissue and reticular tissue).

- Insulation: Adipose tissue provides thermal insulation.

- Transportation: Blood transports substances throughout the body.

- Energy Storage: Adipose tissue stores fat.

- Structural Framework: Providing shape and integrity (e.g., bone, cartilage).

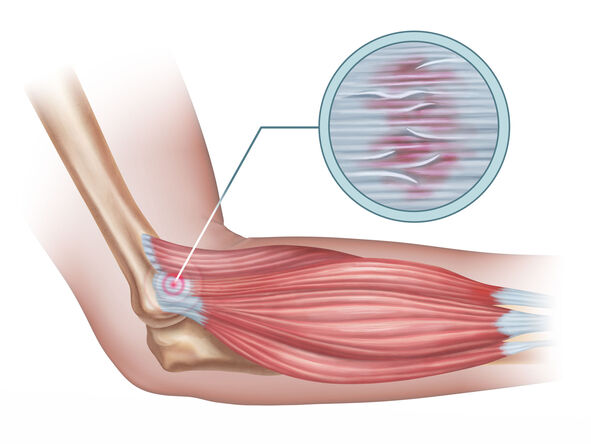

Tendinitis

Tendinitis (or less commonly, tendonitis) is, strictly speaking, an inflammation of a tendon. Tendons are strong, fibrous cords of dense regular connective tissue that attach muscles to bones. They are designed to withstand significant tensile stress, acting as power transmitters from muscle contractions to skeletal movement.

Common Affected Areas:

Tendinitis can occur in any tendon in the body, but it is particularly common in areas subjected to repetitive motion and overuse. Key sites include:

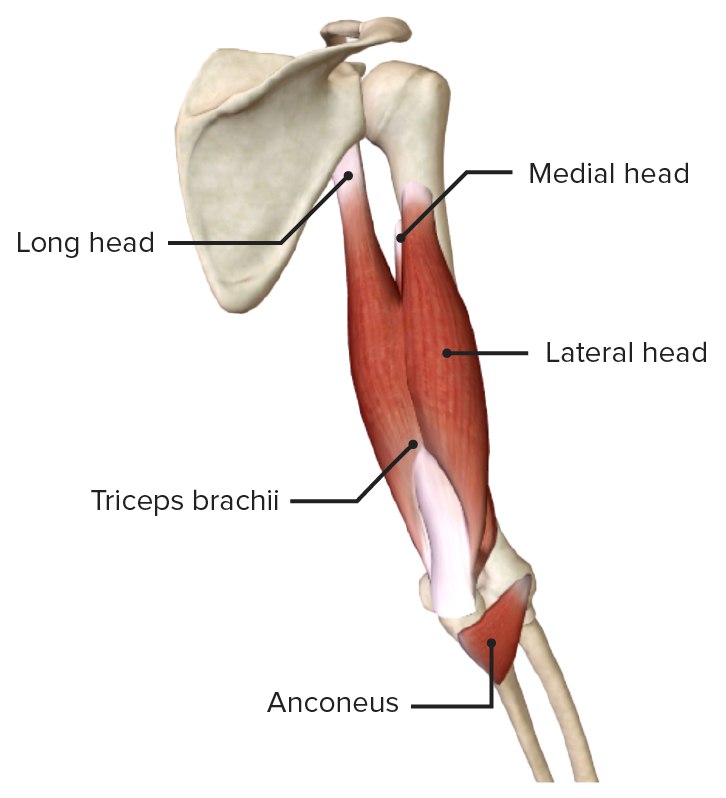

- Shoulder:

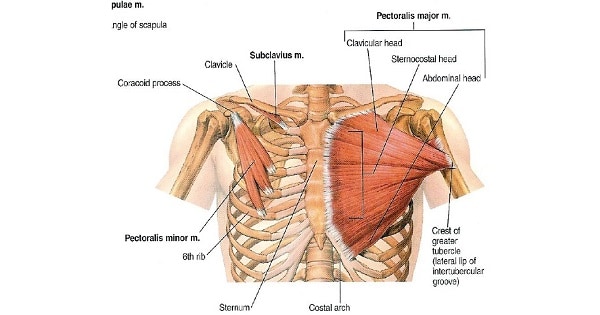

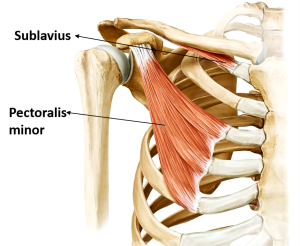

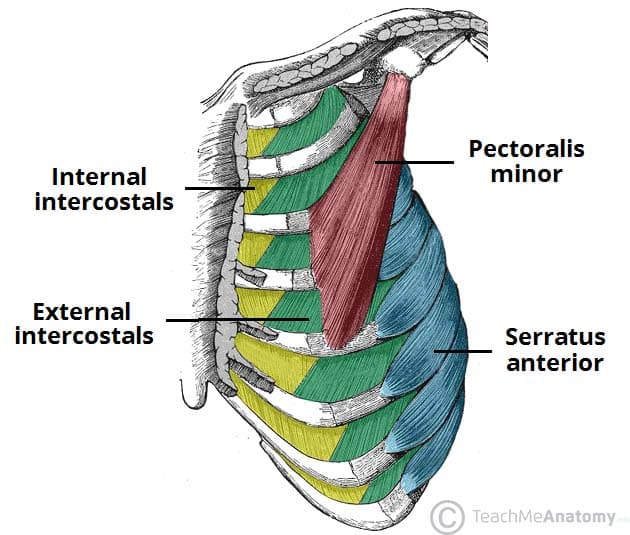

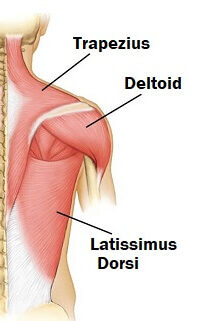

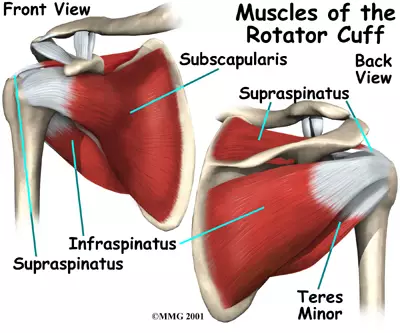

- Rotator Cuff Tendinitis: Involving the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, or subscapularis tendons.

- Bicipital Tendinitis: Affecting the tendon of the long head of the biceps muscle.

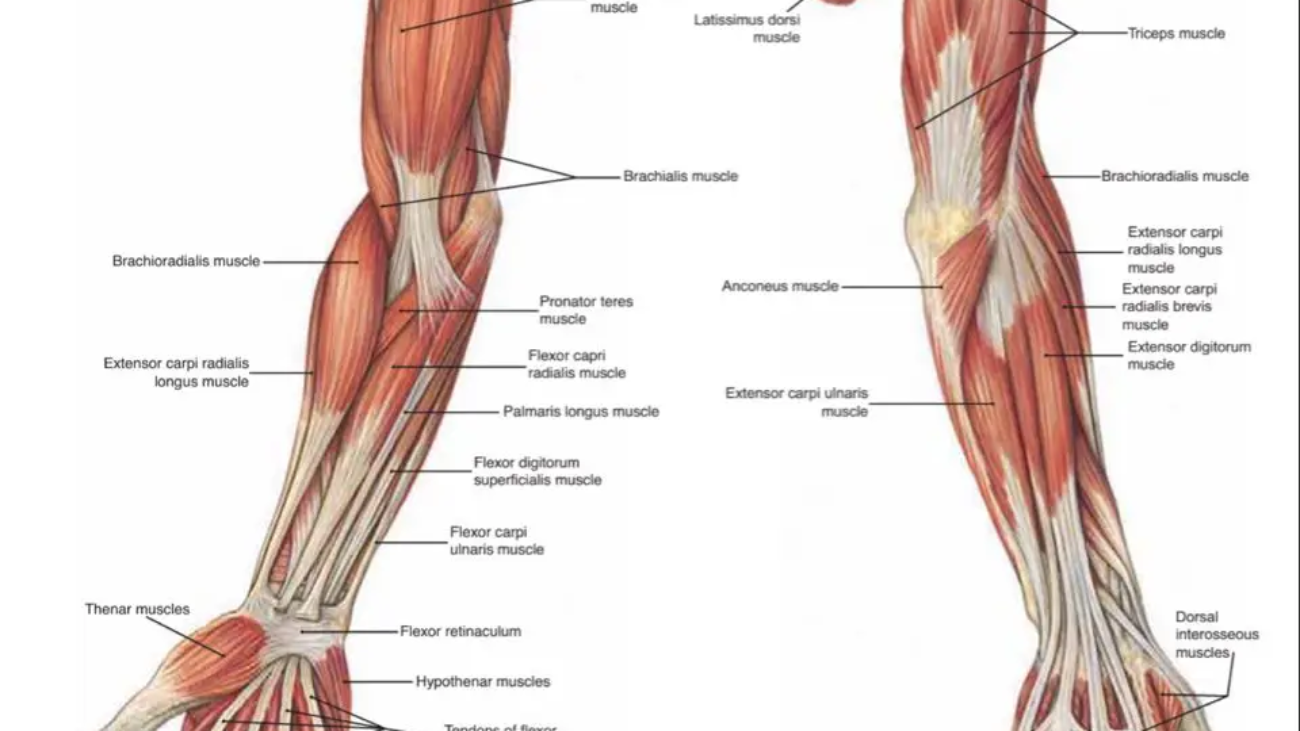

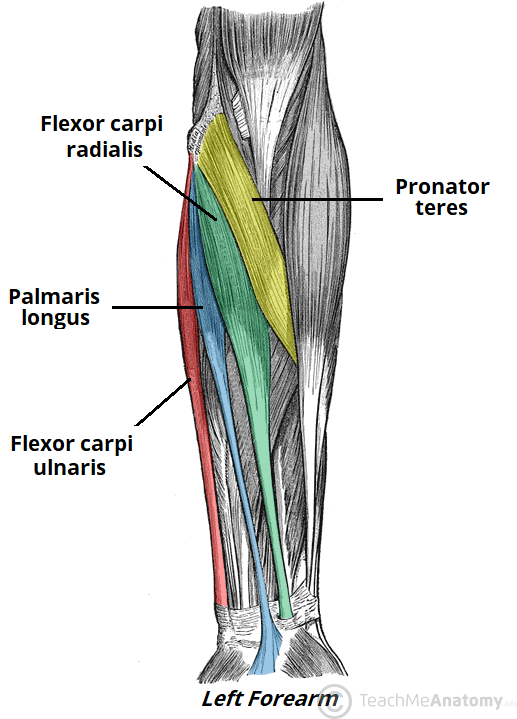

- Elbow:

- Lateral Epicondylitis (Tennis Elbow): Affecting the extensor tendons of the forearm, particularly the extensor carpi radialis brevis, at their attachment to the lateral epicondyle of the humerus.

- Medial Epicondylitis (Golfer's/Little Leaguer's Elbow): Affecting the flexor/pronator tendons at their attachment to the medial epicondyle.

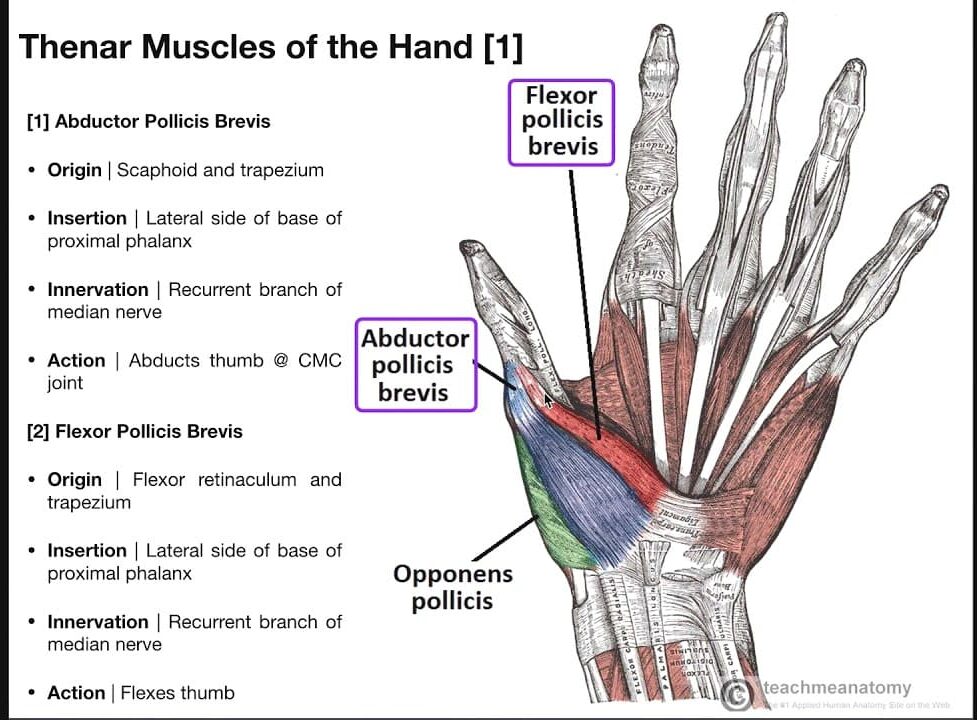

- Wrist and Hand:

- De Quervain's Tenosynovitis: Affecting the tendons on the thumb side of the wrist (abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis).

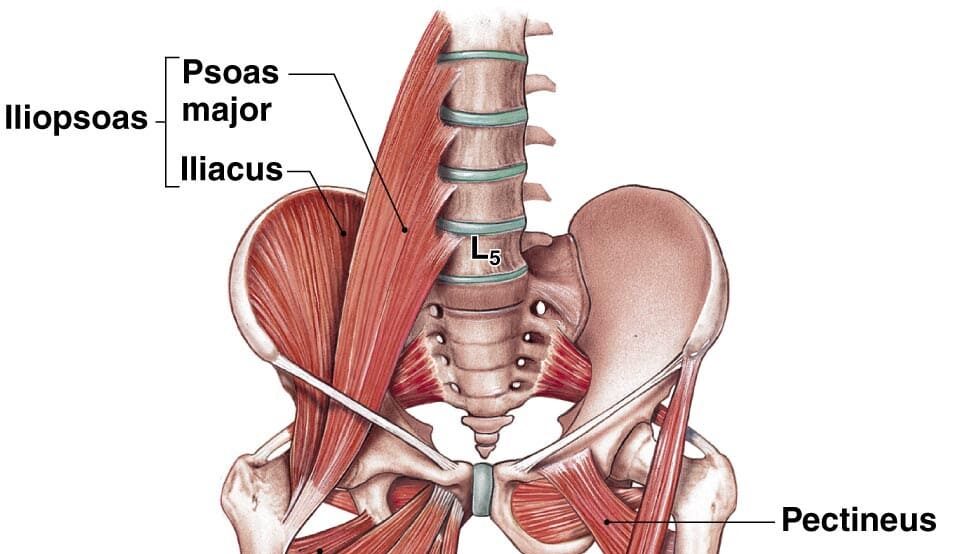

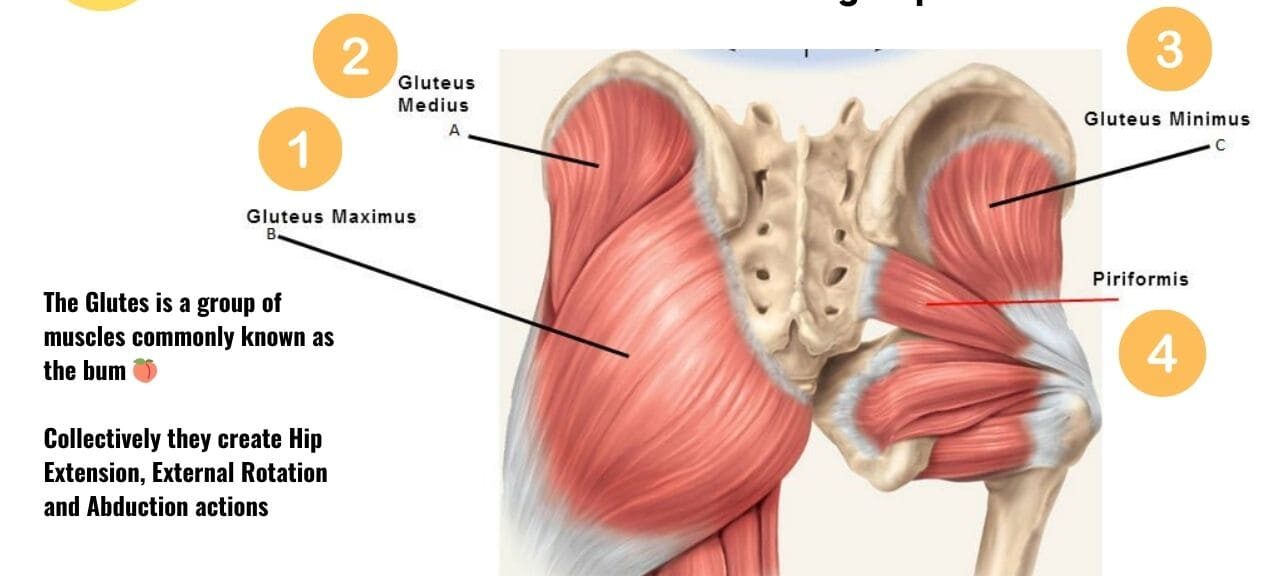

- Hip:

- Gluteal Tendinitis: Involving the tendons of the gluteus medius or minimus.

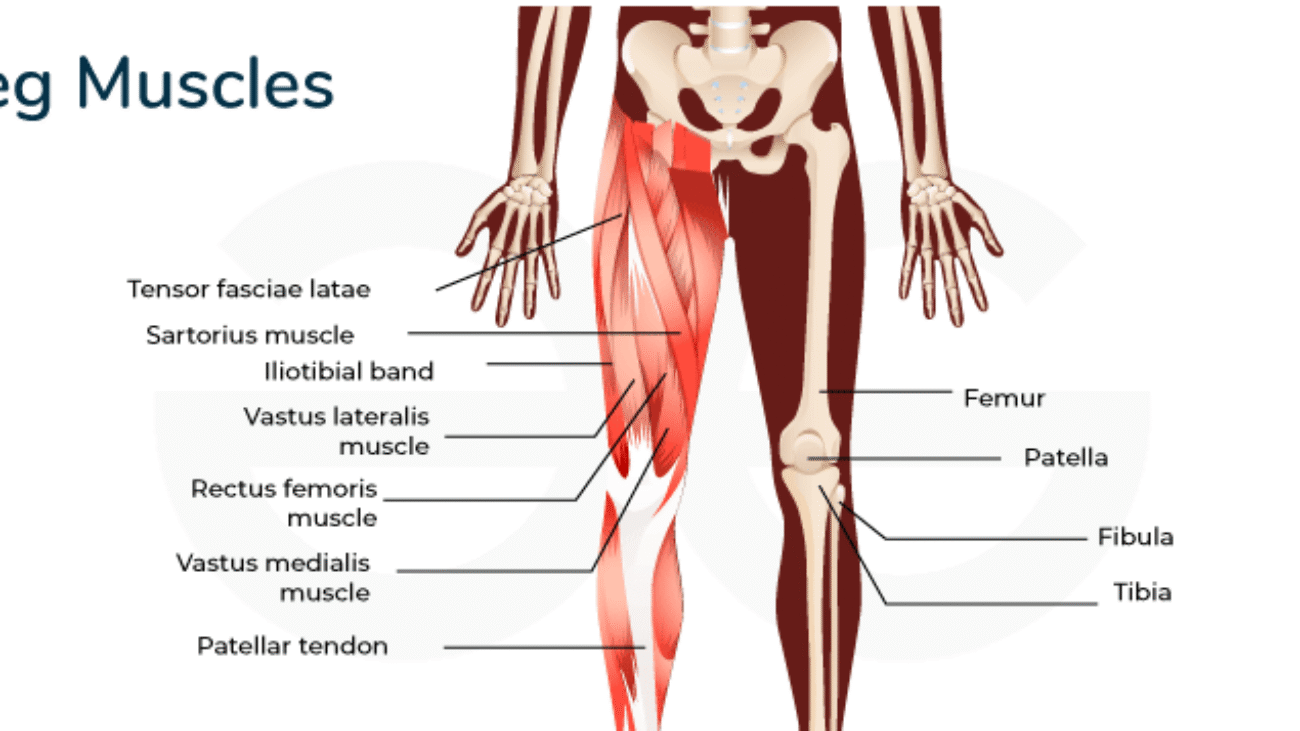

- Knee:

- Patellar Tendinitis (Jumper's Knee): Affecting the patellar tendon, which connects the kneecap (patella) to the shin bone (tibia).

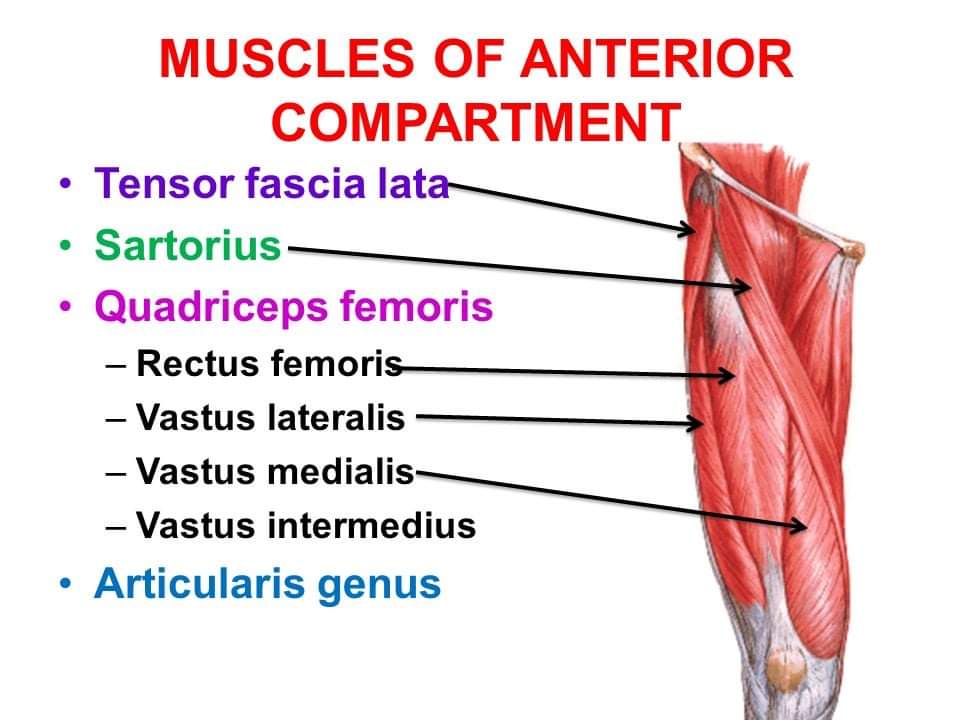

- Quadriceps Tendinitis: Affecting the quadriceps tendon, which connects the quadriceps muscles to the patella.

- Ankle and Foot:

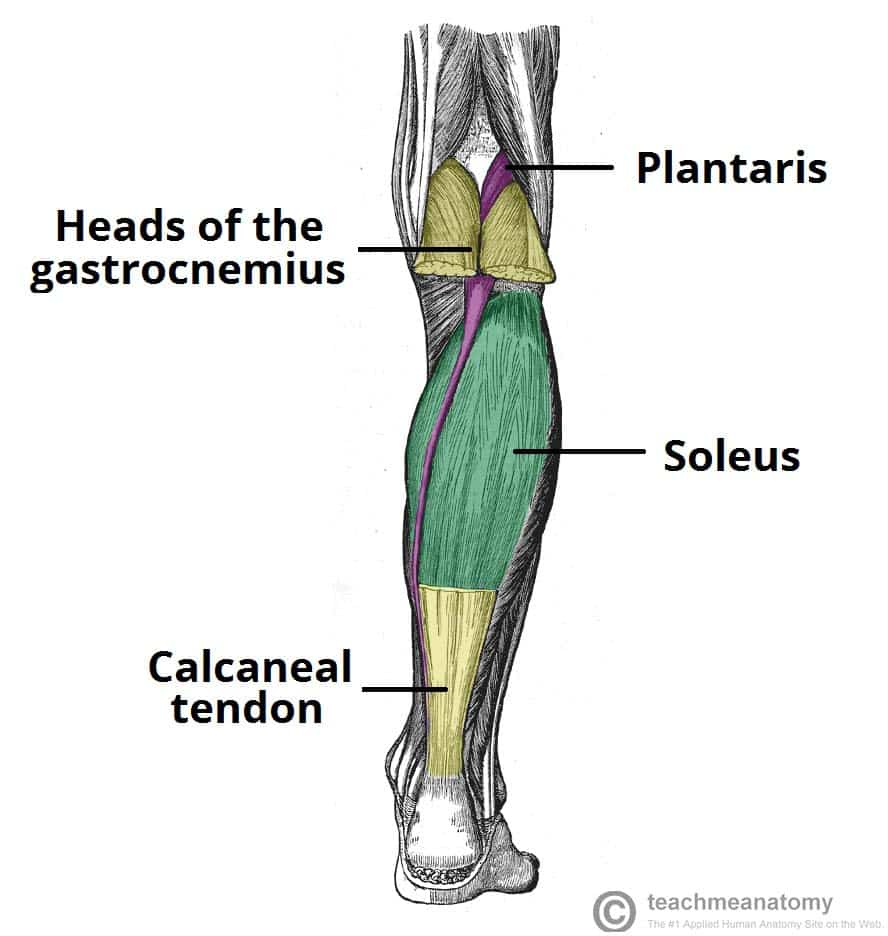

- Achilles Tendinitis: Affecting the Achilles tendon, which connects the calf muscles to the heel bone.

- Posterior Tibial Tendinitis: Affecting the posterior tibial tendon on the inner side of the ankle.

Etiology (Causes) and Pathophysiology (Mechanisms of Disease)

The underlying causes and mechanisms of tendinitis often involve a combination of factors leading to micro-damage and, depending on the chronicity, either an inflammatory response or a degenerative process.

A. Role of Overuse and Repetitive Motion:

- Primary Cause: This is the most common contributing factor. Tendons are designed to handle stress, but repetitive motions, especially those involving eccentric (lengthening) muscle contractions, can exceed the tendon's capacity for repair.

- Mechanism: Repeated small stresses accumulate, leading to microscopic tears in the collagen fibers of the tendon.

B. Role of Microtrauma:

- Direct Injury: A single, sudden, forceful movement or direct impact can cause acute microtrauma.

- Cumulative Microtrauma: More commonly, the tiny tears accumulate over time due to repetitive strain, especially if the tendon isn't given adequate time to recover. This is often seen in athletes, manual laborers, and individuals with hobbies involving repetitive movements (e.g., typing, playing musical instruments).

C. Role of Inflammation (Acute Tendinitis):

- In the acute phase, particularly after a sudden overload or injury, the body initiates an inflammatory response to the microtrauma.

- Process: Inflammatory cells (e.g., neutrophils, macrophages) are recruited to the site, releasing cytokines and other mediators that cause pain, swelling, heat, and redness. This is a normal healing process, but if prolonged or excessive, it can be detrimental.

- Clinical Picture: This acute inflammatory phase is what the term "tendinitis" classically refers to.

D. Role of Degeneration (Chronic Tendinosis):

- When repetitive microtrauma continues without adequate healing, the tendon tissue can undergo degenerative changes, often with minimal or no inflammatory cells present. This is the hallmark of tendinosis.

- Process:

- Collagen Disorganization: The normally well-organized, parallel collagen fibers become disorganized, frayed, and weakened.

- Angiofibroblastic Hyperplasia: There's an increase in immature fibroblasts and new, often disorganized, blood vessels within the tendon. These new vessels can contribute to pain.

- Mucoid Degeneration: Accumulation of ground substance material, leading to a softer, more gelatinous tendon texture.

- Loss of Mechanical Strength: The degenerative changes reduce the tendon's ability to transmit force and withstand stress, making it more susceptible to further injury or rupture.

- Chronic Pain: The absence of classic inflammation often explains why anti-inflammatory medications are less effective for chronic tendinopathy.

E. Other Contributing Factors:

- Age: Tendons naturally lose elasticity and strength with age, making them more susceptible to injury.

- Improper Technique: Poor biomechanics in sports or work can place abnormal stress on tendons.

- Muscle Imbalance/Weakness: Weak muscles supporting a joint can lead to increased tendon strain.

- Inflexibility: Tight muscles can increase tension on their attached tendons.

- Systemic Diseases: Conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and gout can predispose individuals to tendinitis.

- Medications: Certain antibiotics (e.g.,

fluoroquinolones) have been associated with increased risk of tendinopathy and tendon rupture. - Anatomical Abnormalities: Bone spurs or other structural issues can irritate tendons.

Clinical Manifestations (Signs and Symptoms)

The signs and symptoms of tendinitis typically reflect the location and severity of the tendon involvement.

A. Characteristic Pain:

- Location: Localized to the affected tendon, often near its attachment to bone.

- Nature:

- Aching or dull pain at rest, often worsening with activity.

- Sharp, stabbing pain with specific movements that stress the tendon.

- Timing: Often worse after periods of inactivity (e.g., morning stiffness), improves with gentle movement, but then worsens again with prolonged or strenuous activity.

- Referred Pain: In some cases, pain can be referred to adjacent areas.

B. Tenderness:

- Localized Tenderness: The most consistent finding. Direct palpation (touching) of the affected tendon will elicit pain. This tenderness is often very specific to the tendon itself.

C. Swelling:

- Visible Swelling: May or may not be present. More common in acute inflammatory tendinitis or if the tendon sheath (tenosynovitis) is involved.

- Palpable Thickening: In chronic tendinosis, the tendon may feel thickened or nodular due to degenerative changes.

D. Functional Limitations and Impairment:

- Reduced Range of Motion: Pain often limits the ability to move the affected joint through its full range.

- Weakness: Pain with resistance against muscle action can indicate tendon involvement. True weakness may also occur if the tendon is severely damaged.

- Crepitus: A grating or crackling sensation may be felt or heard when moving the affected tendon, especially in cases of tenosynovitis.

- Difficulty with Activities of Daily Living (ADLs): Simple tasks that involve the affected joint can become painful and challenging (e.g., lifting objects, typing, brushing hair).

E. Redness and Warmth:

- Less Common: These classic signs of inflammation (rubor and calor) are generally less prominent than pain and tenderness in pure tendinitis, and even less so in tendinosis. They may be present in acute, severe cases or if there is accompanying bursitis or tenosynovitis.

Diagnosis: Diagnosis is primarily clinical, based on patient history, symptoms, and physical examination (localized tenderness, pain with specific movements). Imaging studies like ultrasound or MRI can help confirm the diagnosis, rule out other conditions (e.g., fracture, complete tendon tear), and assess the degree of degeneration (in tendinosis).

Treatment Principles:

- Rest: Avoiding activities that exacerbate the pain.

- Ice/Heat: For pain and swelling management.

- Pain Management: NSAIDs (especially in acute inflammatory phases), topical analgesics.

- Physical Therapy: Stretching, strengthening, and eccentric exercises to promote tendon healing and strength.

- Biomechanical Correction: Addressing poor posture, technique, or equipment.

- Injections: Corticosteroids (for inflammation, but used cautiously due to potential for tendon weakening), platelet-rich plasma (PRP), prolotherapy.

- Surgery: Rarely needed, usually for chronic cases unresponsive to conservative treatment or in cases of significant tears.

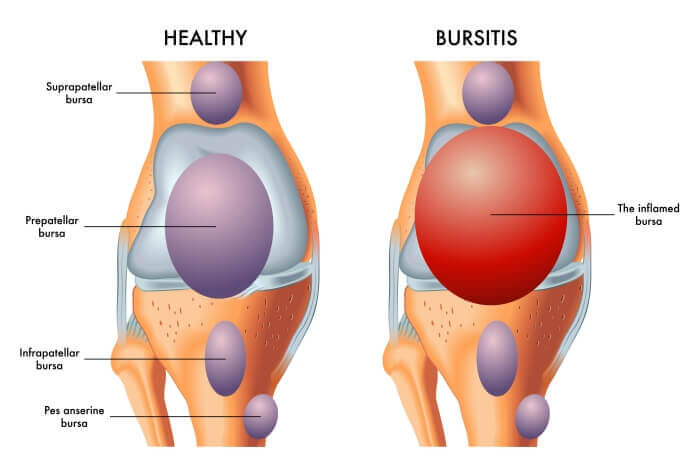

Bursitis:

Bursitis is the inflammation of a bursa. Bursae (plural of bursa) are small, fluid-filled, sac-like structures lined by synovial membrane. They are typically located between bones, tendons, and muscles, or near joints, where they serve as cushions to reduce friction and allow for smooth movement between adjacent structures. They contain a small amount of synovial fluid, similar in composition to that found in joints.

Common Affected Bursae:

Bursitis can occur in any of the approximately 150 bursae in the human body, but it is most common in large joints that undergo repetitive motion or are subjected to pressure. Key sites include:

- Shoulder:

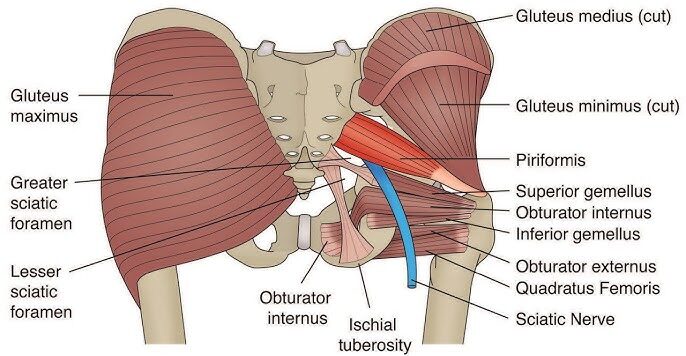

- Subacromial (or Subdeltoid) Bursitis: The most common site. This bursa lies between the rotator cuff tendons and the acromion of the scapula. Often associated with rotator cuff tendinitis/impingement.

- Elbow:

- Olecranon Bursitis: (Miner's/Student's Elbow): Affects the bursa located over the bony prominence of the elbow (olecranon).

- Hip:

- Trochanteric Bursitis: Affects the bursa located over the greater trochanter of the femur (the bony bump on the side of the hip).

- Ischial Bursitis (Weaver's Bottom): Affects the bursa between the ischial tuberosity (the bony prominence you sit on) and the gluteus maximus.

- Knee:

- Prepatellar Bursitis (Housemaid's Knee): Affects the bursa located directly in front of the kneecap (patella).

- Infrapatellar Bursitis (Clergyman's Knee): Affects the bursa located below the kneecap.

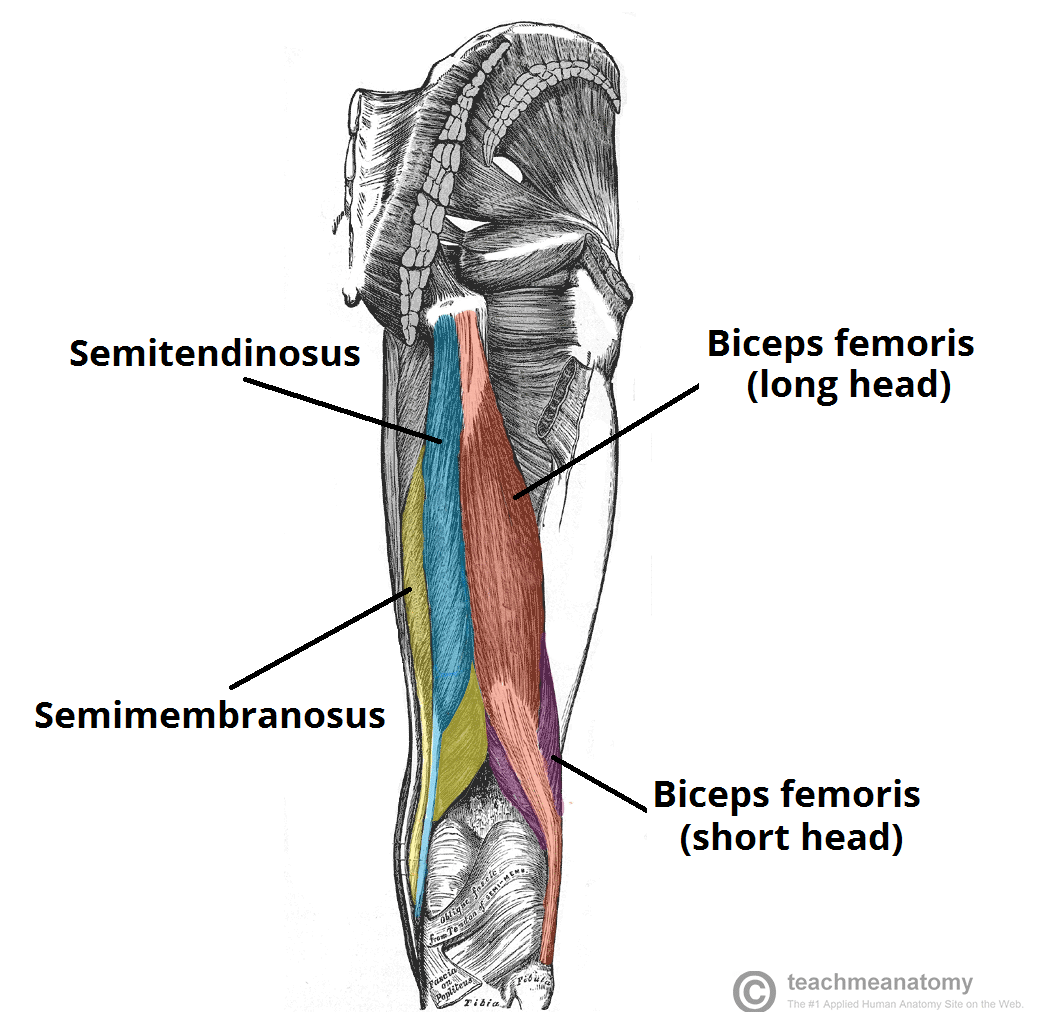

- Pes Anserine Bursitis: Affects the bursa located on the inner side of the knee, beneath the tendons of the sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus muscles.

- Ankle/Foot:

- Retrocalcaneal Bursitis: Affects the bursa located between the Achilles tendon and the heel bone (calcaneus).

Etiology (Causes) and Pathophysiology (Mechanisms of Disease)

The underlying causes and mechanisms of bursitis involve factors that lead to irritation or direct damage to the bursa, triggering an inflammatory response.

A. Role of Trauma:

- Acute Trauma: A direct blow or fall onto a bursa can cause immediate irritation and inflammation. For example, falling directly onto the elbow can cause olecranon bursitis.

- Repetitive Microtrauma/Pressure: Sustained pressure or repeated friction on a bursa is a very common cause.

- Examples: Kneeling frequently (prepatellar bursitis), prolonged sitting on hard surfaces (ischial bursitis), repetitive arm movements against the acromion (subacromial bursitis).

B. Role of Overuse and Repetitive Motion:

- Similar to tendinitis, repetitive movements that involve the sliding of a tendon or muscle over a bursa can lead to friction and irritation.

- Mechanism: When the surrounding tendons or muscles rub excessively against the bursa, the lining of the bursa becomes inflamed and produces excess synovial fluid, causing the bursa to swell and become painful.

- Examples: Overhead activities in sports (swimming, throwing) can cause subacromial bursitis. Running or cycling can exacerbate trochanteric or pes anserine bursitis.

C. Role of Infection (Septic Bursitis):

- This is a less common but more serious cause, especially in superficial bursae (e.g., olecranon, prepatellar) that are susceptible to skin breaks.

- Mechanism: Bacteria (most commonly

Staphylococcus aureus) can enter the bursa through a cut, scrape, insect bite, or even an injection site, leading to a bacterial infection within the bursa. - Pathophysiology: The infection triggers a robust inflammatory response, often with pus formation (suppurative bursitis). This can lead to rapid onset of severe pain, marked swelling, redness, warmth, and potentially systemic symptoms like fever and chills.

- Clinical Importance: Septic bursitis requires prompt medical attention and antibiotic treatment to prevent local tissue damage or systemic infection (sepsis).

D. Other Contributing Factors:

- Systemic Inflammatory Conditions: Conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, gout, pseudogout, and ankylosing spondylitis can cause inflammatory bursitis as part of their systemic manifestations.

- Calcium Deposits: Sometimes, calcium crystals can form within a bursa, leading to irritation and inflammation.

- Bone Spurs/Anatomical Variants: Bony abnormalities can increase friction on adjacent bursae.

- Poor Biomechanics/Posture: Like tendinitis, improper body mechanics can place undue stress on bursae.

Pathophysiology (General Inflammatory Response):

Regardless of the trigger (trauma, overuse, or infection), the primary pathophysiological event in bursitis is an inflammatory response within the bursa. This involves:

- Increased Fluid Production: The synovial cells lining the bursa produce an excessive amount of synovial fluid.

- Bursal Distension: The increased fluid volume causes the bursa to swell and stretch, putting pressure on surrounding tissues and nerve endings.

- Inflammatory Mediators: Release of cytokines, prostaglandins, and other inflammatory chemicals, which contribute to pain and further fluid accumulation.

- Thickening of Bursal Walls: In chronic cases, the bursal walls can thicken and become fibrotic.

Clinical Manifestations (Signs and Symptoms)

The signs and symptoms of bursitis are largely characterized by localized inflammation, pain, and restricted movement.

A. Pain:

- Localized Pain: Typically sharp or aching, located directly over the affected bursa.

- Worsening with Movement: Pain is often exacerbated by specific movements that involve the bursa or by direct pressure on the bursa.

- Rest Pain: Can be present, especially at night or after activity.

- Referred Pain: Less common than in tendinitis, but can occur depending on the bursa's location.

B. Swelling:

- Visible or Palpable Swelling: This is a hallmark sign, especially in superficial bursae (e.g., olecranon, prepatellar). The affected area may appear "puffy" or have a noticeable lump.

- Fluid Accumulation: The bursa fills with excess fluid, making it feel soft and compressible upon palpation.

C. Tenderness:

- Localized Tenderness: Extreme tenderness to touch directly over the inflamed bursa is a consistent finding.

D. Restricted Movement:

- Painful Range of Motion: Movement of the adjacent joint or structures that involve the bursa will often elicit pain, leading to a restricted (though often full) range of motion due to pain rather than a structural block.

- Weakness: Less common as a primary symptom compared to tendinitis, but severe pain can lead to guarding and apparent weakness.

E. Redness and Warmth (Rubor and Calor):

- Common, especially in superficial bursae: The skin overlying an inflamed bursa may appear red and feel warm to the touch. This is more pronounced in acute or septic bursitis.

- Crucial Indicator for Septic Bursitis: The presence of significant redness and warmth, combined with fever or chills, strongly suggests an infection and warrants immediate medical evaluation.

Diagnosis: Diagnosis is primarily clinical, based on the characteristic localized pain, tenderness, swelling, and exacerbation with specific movements or pressure. Imaging (ultrasound, MRI) can help confirm the diagnosis, visualize bursal distension, and rule out other pathologies. Aspiration of bursal fluid (removing fluid with a needle) is crucial if septic bursitis is suspected, allowing for fluid analysis (cell count, Gram stain, culture) to identify infection.

Treatment Principles:

- Rest/Activity Modification: Avoiding activities that irritate the bursa.

- Ice: To reduce inflammation and pain.

- NSAIDs: Oral or topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Physical Therapy: To address underlying biomechanical issues, improve flexibility, and strengthen surrounding muscles.

- Corticosteroid Injections: Injecting a corticosteroid directly into the bursa can significantly reduce inflammation and pain, but repeated injections are generally avoided due to potential side effects.

- Antibiotics: Absolutely necessary for septic bursitis.

- Aspiration: Draining fluid from the bursa can relieve pressure and pain, and is part of the diagnostic process for infection.

- Surgery (Bursectomy): Rarely performed, usually for chronic, recurrent, or septic bursitis unresponsive to conservative measures, where the bursa is surgically removed.

Osteoarthritis (OA)

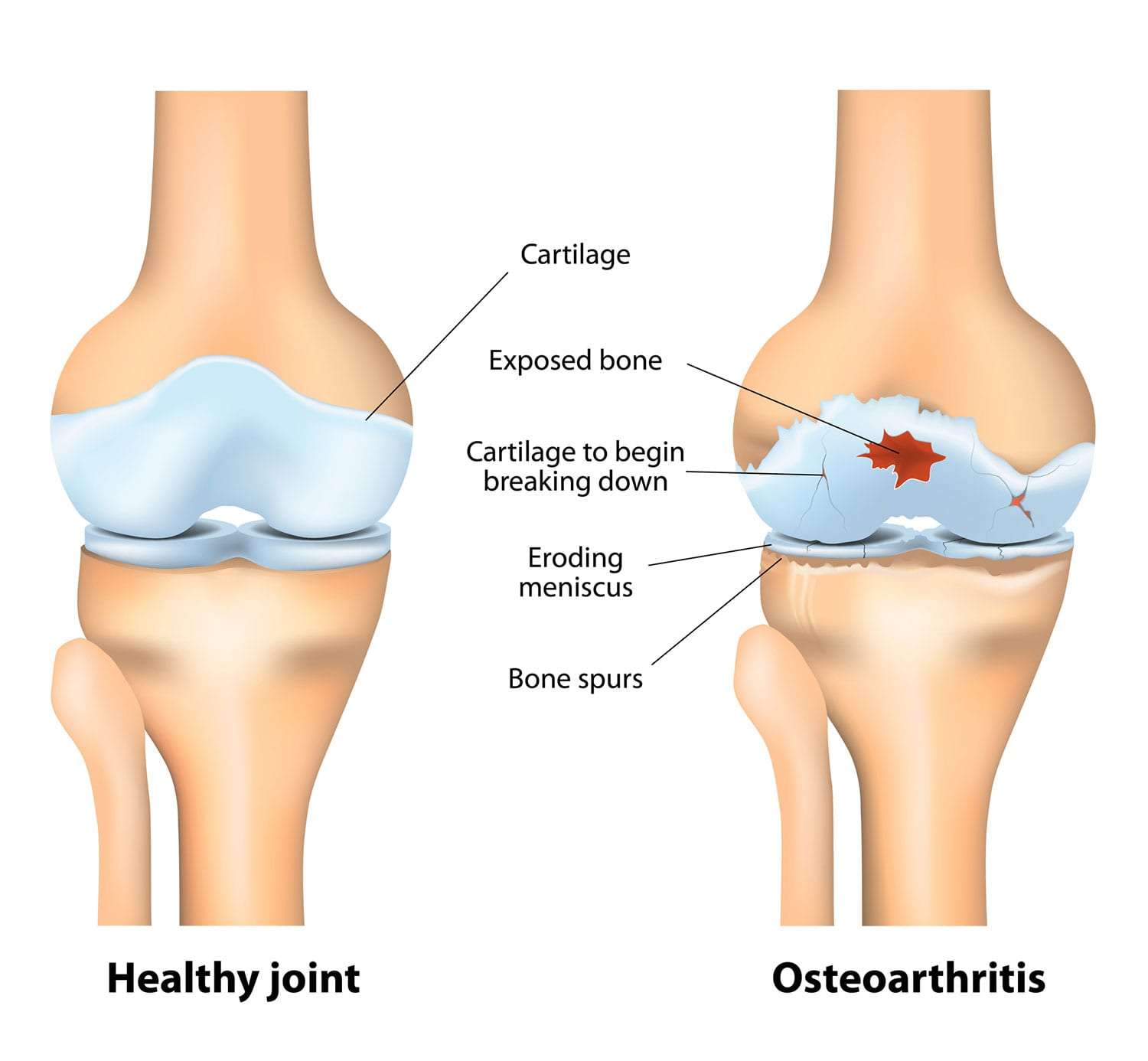

Osteoarthritis (OA), often referred to as "wear-and-tear" arthritis or degenerative joint disease, is the most common form of arthritis. It is a chronic, progressive disorder characterized by the breakdown of articular cartilage in synovial joints, leading to structural and functional changes in the entire joint.

Unlike inflammatory arthropathies (like Rheumatoid Arthritis), OA is primarily considered a disorder of joint failure where the cartilage degenerates, followed by secondary changes in the subchondral bone, synovium, and surrounding soft tissues. It is not purely an aging phenomenon but a disease process that becomes more prevalent with age.

Etiology (Causes) and Pathophysiology (Mechanisms of Disease)

The etiology of OA is multifactorial, involving a complex interplay of mechanical, biological, genetic, and metabolic factors. The pathophysiology centers around the degradation of articular cartilage and the subsequent reactive changes in the underlying bone.

A. Role of Mechanical Stress and Joint Overload:

- Repetitive Microtrauma: Prolonged or excessive mechanical stress on a joint, especially over years, is a primary driver. This can be due to:

- High-Impact Activities: Certain sports (e.g., long-distance running, professional sports that place high loads on joints).

- Occupational Stress: Jobs requiring repetitive kneeling, heavy lifting, or prolonged standing.

- Joint Malalignment: Deformities like bow-legs (varus) or knock-knees (valgus) can create uneven stress distribution across the joint surface.

- Mechanism: Mechanical stress initially causes micro-damage to the cartilage matrix. Chondrocytes (cartilage cells) in response attempt to repair this damage, but if the stress is chronic and exceeds their repair capacity, a degenerative cascade begins.

B. Role of Age:

- Increased Prevalence with Age: OA is strongly age-dependent, with most individuals over 60 showing some radiographic evidence of OA.

- Mechanism: With aging, articular cartilage naturally loses some of its resilience and ability to repair. Chondrocyte activity declines, the proteoglycan content of the matrix decreases (reducing its water-holding capacity), and collagen fibers become more susceptible to damage.

- Cumulative Effect: Over a lifetime, joints accumulate micro-injuries and undergo biochemical changes that make them more vulnerable to OA.

C. Role of Obesity:

- Increased Mechanical Load: Excess body weight significantly increases the mechanical load on weight-bearing joints, particularly the knees and hips. Every pound of body weight adds several pounds of force across the knees.

- Metabolic Factors: Adipose tissue is metabolically active and produces pro-inflammatory cytokines (adipokines like leptin, resistin) that can have systemic effects and directly contribute to cartilage degradation and inflammation in joints, even non-weight-bearing ones (e.g., hands). This suggests that obesity contributes to OA through both mechanical and metabolic pathways.

D. Role of Genetic Factors:

- Familial Predisposition: A family history of OA, particularly in the hands and hips, increases an individual's risk.

- Specific Genes: Genetic variations may influence the quality of collagen, proteoglycans, or enzymes involved in cartilage maintenance and repair. Genes related to bone density and joint structure can also play a role.

E. Other Contributing Factors:

- Previous Joint Injury/Trauma (Post-traumatic OA): Fractures involving joint surfaces, ligament tears (e.g., ACL rupture), or meniscal tears can significantly accelerate OA development in that joint. This is a common cause of OA in younger individuals.

- Developmental Abnormalities: Congenital hip dysplasia, Legg-Calve-Perthes disease, or other joint malformations.

- Inflammatory Arthritis: While OA is non-inflammatory, prior inflammatory joint diseases (e.g., RA, septic arthritis) can damage cartilage and lead to secondary OA.

- Muscle Weakness: Weakness in muscles surrounding a joint can lead to joint instability and increased stress.

- Gender: Women tend to have a higher prevalence of OA, particularly after menopause, suggesting a hormonal influence.

Pathophysiology: The Cascade of Cartilage Loss and Bone Changes

- Initial Cartilage Damage:

- Starts with micro-cracks and fibrillation (fraying) of the superficial layers of articular cartilage due to mechanical stress or biochemical changes.

- Chondrocytes initially try to repair the damage by increasing proteoglycan and collagen synthesis.

- Chondrocyte Dysfunction:

- Over time, chondrocytes become less efficient at repair and may even undergo apoptosis (programmed cell death).

- They begin to release degradative enzymes (e.g., matrix metalloproteinases - MMPs, aggrecanases) that break down the cartilage matrix faster than it can be synthesized.

- The balance between cartilage synthesis and degradation shifts heavily towards degradation.

- Progressive Cartilage Loss:

- The cartilage loses its elasticity and shock-absorbing capacity.

- It thins, softens, and develops deeper fissures and erosions, eventually exposing the underlying subchondral bone.

- Subchondral Bone Changes:

- Bone Sclerosis: The exposed subchondral bone thickens and becomes denser (sclerosis) in response to increased mechanical load.

- Bone Cysts: Small fluid-filled cysts (subchondral cysts) can form within the bone.

- Osteophytes (Bone Spurs): New bone outgrowths (osteophytes) develop at the joint margins, likely an attempt by the body to stabilize the joint or increase the surface area for load bearing. These can contribute to pain and limit joint motion.

- Synovial Involvement:

- Fragments of cartilage and bone can break off and irritate the synovial membrane, causing mild inflammation (secondary synovitis).

- The synovial fluid may become less viscous due to a decrease in hyaluronic acid, further impairing lubrication.

- Joint Capsule and Ligament Changes:

- The joint capsule can thicken and contract. Ligaments may become lax or stiff, further destabilizing the joint.

Clinical Manifestations (Signs and Symptoms)

The clinical manifestations of OA typically develop insidiously and progress over years.

A. Joint Pain:

- "Activity-related" Pain: The most characteristic symptom. Pain worsens with joint use (weight-bearing, movement) and is typically relieved by rest.

- Morning Stiffness: Brief (usually less than 30 minutes), localized stiffness after periods of rest, easing with movement. This differentiates it from the prolonged morning stiffness of inflammatory arthritis like RA.

- Pain at Night: As the disease progresses, pain can become constant and interfere with sleep, even at rest.

- Location: Most commonly affects weight-bearing joints (knees, hips, spine) and hands (DIP and PIP joints, base of the thumb), but can affect any joint.

B. Joint Stiffness:

- Post-Rest Stiffness: Stiffness after inactivity or prolonged sitting ("gelling" phenomenon).

- Reduced Range of Motion (ROM): As cartilage loss and osteophyte formation progress, the ability to fully bend or straighten the joint decreases.

C. Crepitus:

- A grinding, crackling, or popping sound or sensation within the joint during movement. This occurs due to the roughened cartilage surfaces rubbing against each other or due to osteophyte friction.

D. Swelling (Effusion):

- Mild or Intermittent: Swelling can occur due to synovial inflammation (secondary synovitis) or accumulation of joint fluid (effusion) in response to irritation. It is typically less prominent and less warm than in inflammatory arthritides.

E. Joint Deformity and Instability:

- Bony Enlargement: Osteophyte formation (bone spurs) can lead to visible and palpable enlargement of the joint, especially in the hands (Heberden's nodes at DIP joints, Bouchard's nodes at PIP joints).

- Malalignment: Asymmetric cartilage loss can lead to joint misalignment (e.g., bow-leggedness in knee OA).

- Instability: Weakness of surrounding muscles or ligamentous laxity can lead to a feeling of the joint "giving way."

F. Tenderness:

- Localized tenderness when pressing on the joint line or surrounding tissues.

G. Functional Impairment:

- Difficulty performing activities of daily living (ADLs) such as walking, climbing stairs, dressing, or grasping objects, significantly impacting quality of life.

Diagnosis: Diagnosis is primarily based on clinical history, physical examination, and radiographic findings (X-rays). X-rays typically show joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophyte formation. Blood tests are usually normal (no inflammatory markers like ESR or CRP elevation, which are characteristic of RA).

Treatment Principles:

Treatment aims to manage pain, improve function, and slow disease progression:

- Non-Pharmacological: Weight management, exercise (strengthening, low-impact aerobics), physical therapy, assistive devices, heat/cold therapy, patient education.

- Pharmacological:

- Topical/Oral Analgesics: Acetaminophen, NSAIDs (oral and topical).

- Intra-articular Injections: Corticosteroids (for acute flares), hyaluronic acid (viscosupplementation).

- Surgical: Arthroscopy (for specific issues like loose bodies), osteotomy (to realign the joint), and ultimately, joint replacement (arthroplasty) for severe, end-stage OA (e.g., total knee or hip replacement).

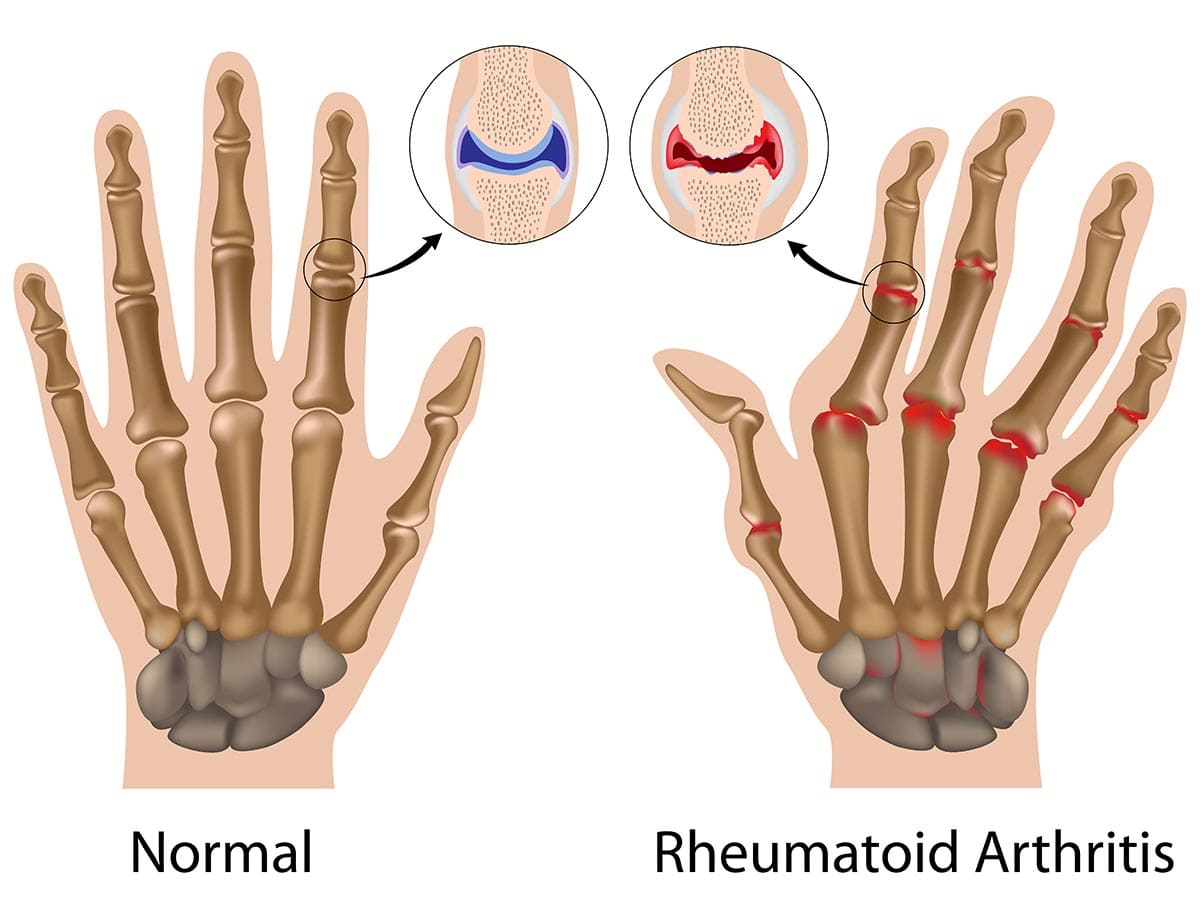

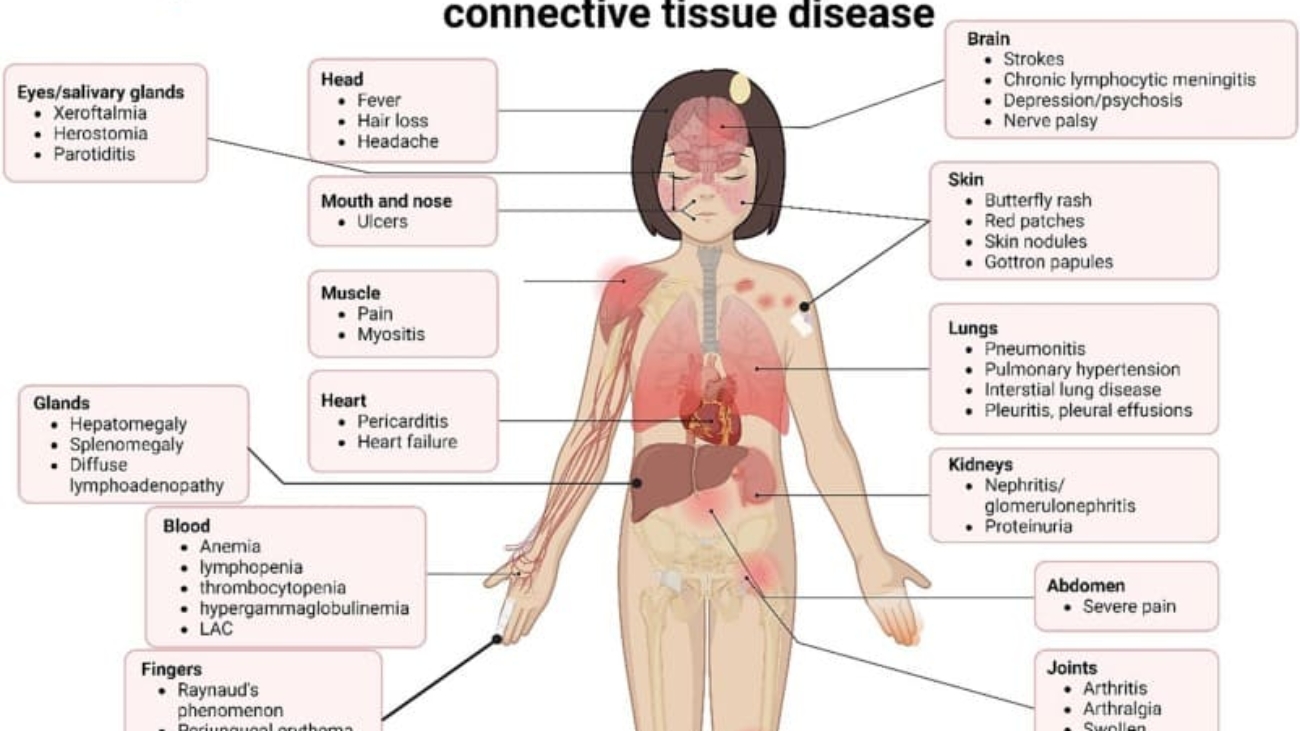

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic autoimmune inflammatory disease that primarily targets the synovial membranes of joints, leading to inflammation, pain, swelling, and eventually, joint destruction and deformity. While joints are the primary target, RA can also affect other organs, including the skin, eyes, lungs, heart, and blood vessels.

Unlike OA, which is primarily a "wear-and-tear" degenerative condition, RA is characterized by the immune system mistakenly attacking the body's own tissues, specifically the synovium (the lining of the joint capsule). This persistent inflammation leads to significant morbidity and functional impairment if not adequately treated.

Etiology (Causes) and Pathophysiology (Mechanisms of Disease)

The exact cause of RA is unknown, but it is understood to be a complex interplay of genetic susceptibility, environmental triggers, and an aberrant immune response.

A. Role of Genetic Predisposition:

- Strong Genetic Link: Family history is a significant risk factor. Identical twins have a much higher concordance rate for RA than fraternal twins.

- HLA Genes: The strongest genetic association is with certain alleles of the Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) genes, particularly HLA-DRB1. These genes are crucial for presenting antigens to T cells, suggesting a fundamental role in initiating the autoimmune response.

- Non-HLA Genes: Multiple other genes are also implicated, contributing to immune regulation and inflammation pathways.

B. Role of Environmental Triggers:

- Smoking: Tobacco smoking is the most consistently identified environmental risk factor for RA, particularly in individuals with genetic predisposition (HLA-DRB1). It is thought to induce post-translational modifications (e.g., citrullination) of proteins, making them appear "foreign" to the immune system.

- Infections: Certain bacterial or viral infections (e.g., Epstein-Barr virus, periodontal disease) have been hypothesized to act as triggers, perhaps through molecular mimicry (where microbial antigens resemble self-antigens) or by activating immune cells.

- Other Factors: Exposure to silica, changes in gut microbiota, and certain occupational exposures have also been investigated.

C. Role of Immune System Dysfunction (Autoimmunity):

The core of RA pathophysiology is an uncontrolled and sustained autoimmune attack on the synovial membrane.

Pathophysiology: The Autoimmune Cascade

- Initiation: In genetically susceptible individuals, an environmental trigger (e.g., smoking) is thought to initiate an immune response against a "self" protein (e.g., citrullinated peptides).

- Antigen Presentation: Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the synovium or lymphatic tissue pick up these modified self-antigens and present them to T-helper cells (CD4+ T cells).

- T-cell Activation: Activated T-helper cells release cytokines that stimulate other immune cells and B cells.

- B-cell Activation and Autoantibody Production: Activated B cells differentiate into plasma cells and produce autoantibodies, notably:

- Rheumatoid Factor (RF): Antibodies (usually IgM) directed against the Fc portion of IgG.

- Anti-Citrullinated Protein Antibodies (ACPA or anti-CCP): Highly specific antibodies directed against proteins that have undergone citrullination. ACPAs are often present years before clinical symptoms and are a strong predictor of severe disease.

- Synovial Inflammation (Synovitis): The activated T cells, B cells, macrophages, and autoantibodies infiltrate the synovial membrane.

- This leads to a massive inflammatory response with proliferation of synovial cells, increased vascularity, and accumulation of inflammatory cells.

- The synovium becomes hypertrophied and edematous.

- Pannus Formation: The inflamed, thickened synovial tissue expands and forms an aggressive, destructive vascular granulation tissue called pannus.

- The pannus invades and erodes the adjacent articular cartilage, subchondral bone, and ultimately ligaments and tendons.

- Cartilage and Bone Destruction:

- Enzyme Release: Cells within the pannus (fibroblasts, macrophages) release a host of destructive enzymes (MMPs, cathepsins) that degrade the collagen and proteoglycans of the articular cartilage.

- Osteoclast Activation: Pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-alpha, IL-1, IL-6) directly activate osteoclasts, leading to bone resorption and erosions, particularly at the "bare areas" of the joint not covered by cartilage.

- Joint Deformity and Dysfunction:

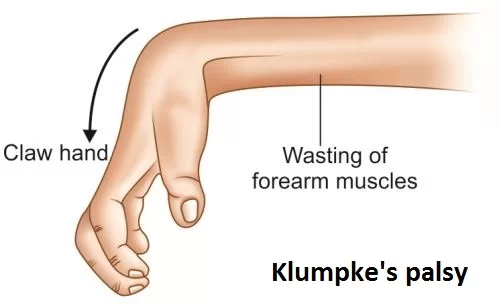

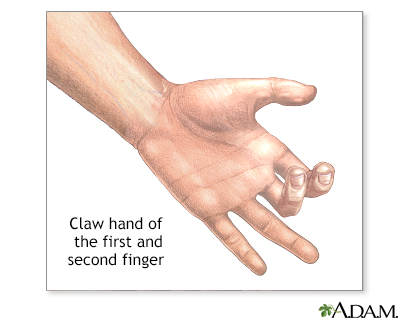

- Loss of cartilage and bone, combined with stretching and weakening of ligaments and tendons by the destructive pannus, leads to joint instability, subluxation (partial dislocation), and characteristic deformities (e.g., ulnar deviation of fingers, swan-neck and boutonnière deformities).

- This ultimately results in significant functional impairment and disability.

Clinical Manifestations (Signs and Symptoms)

RA typically presents with a symmetrical polyarthritis (affecting multiple joints on both sides of the body) and can also have systemic features.

A. Joint Symptoms:

- Symmetrical Polyarthritis: Most characteristic. Affects multiple joints on both sides of the body simultaneously.

- Small Joints First: Often begins in the small joints of the hands and feet (metacarpophalangeal - MCP, proximal interphalangeal - PIP joints of fingers; metatarsophalangeal - MTP joints of toes). Wrists, elbows, shoulders, knees, and ankles can also be affected. Distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints are typically spared in RA but are commonly affected in OA.

- Pain: Often described as aching, throbbing, or burning. Worse after rest and improved with activity.

- Stiffness:

- Prolonged Morning Stiffness: A hallmark feature, lasting at least 30 minutes, often several hours, and improving with activity. This is a key differentiator from OA.

- Stiffness after periods of inactivity (gelling).

- Swelling (Synovitis): Soft, spongy, warm swelling due to synovial inflammation and fluid accumulation. Often palpable.

- Tenderness: Very tender to touch, especially along the joint lines.

- Loss of Range of Motion: Due to pain, swelling, and eventual joint destruction.

- Joint Deformities: In chronic, uncontrolled RA:

- Ulnar Deviation: Fingers drift towards the little finger.

- Swan-Neck Deformity: Hyperextension of PIP joint, flexion of DIP joint.

- Boutonnière Deformity: Flexion of PIP joint, hyperextension of DIP joint.

- Z-thumb Deformity: Flexion at the MCP joint and hyperextension at the interphalangeal (IP) joint of the thumb.

- Hammer toes/Claw toes: In the feet.

B. Systemic Symptoms (Constitutional Symptoms):

- Fatigue: A very common and often debilitating symptom, sometimes out of proportion to joint pain.

- Malaise: A general feeling of discomfort, illness, or uneasiness.

- Low-grade Fever: Occasional.

- Weight Loss: Unexplained weight loss can occur.

- Anorexia: Loss of appetite.

C. Extra-Articular Manifestations (Beyond the Joints):

RA can affect almost any organ system, indicating its systemic nature.

- Rheumatoid Nodules: Firm, non-tender lumps that develop under the skin, especially over pressure points (e.g., elbow, fingers). Can also occur in internal organs (lungs, heart).

- Eyes: Scleritis (inflammation of the sclera), episcleritis, dry eyes (Sjögren's syndrome).

- Lungs: Pleurisy, pleural effusions, interstitial lung disease, rheumatoid nodules in the lungs.

- Heart: Pericarditis, myocarditis, increased risk of cardiovascular disease (e.g., atherosclerosis).

- Blood Vessels: Vasculitis (inflammation of blood vessels), leading to skin ulcers, nerve damage.

- Blood: Anemia of chronic disease, Felty's syndrome (RA, splenomegaly, neutropenia).

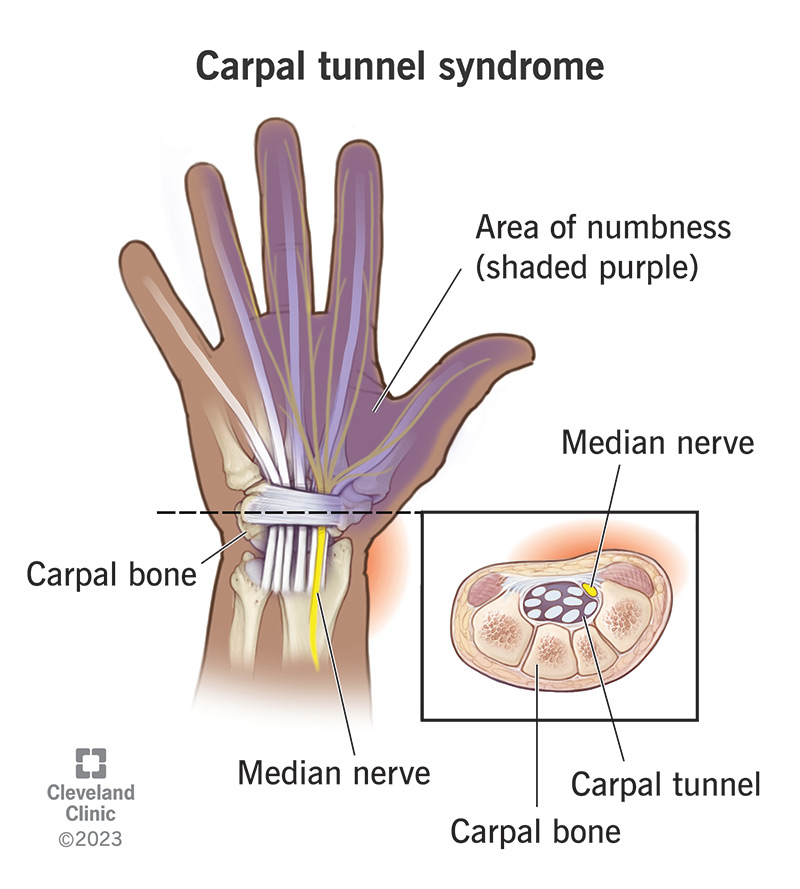

- Nervous System: Nerve entrapment (e.g., carpal tunnel syndrome), cervical myelopathy (due to atlantoaxial subluxation).

Diagnosis: Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical criteria (symmetrical synovitis, prolonged morning stiffness), laboratory tests, and imaging.

- Blood Tests:

- Rheumatoid Factor (RF): Positive in ~70-80% of patients.

- Anti-Citrullinated Protein Antibodies (ACPA/anti-CCP): Highly specific (90-98%) and often present early.

- Inflammatory Markers: Elevated Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) reflect systemic inflammation.

- Imaging: X-rays show joint space narrowing, erosions, and osteopenia (bone thinning) around the joints. MRI and ultrasound can detect early synovitis and erosions.

Treatment Principles:

Treatment aims to reduce inflammation, prevent joint damage, manage pain, and improve function. Early diagnosis and aggressive treatment are crucial to prevent irreversible joint destruction.

- Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs): The cornerstone of RA treatment.

- Conventional Synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs):

Methotrexate(first-line), sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide. - Biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs): Target specific inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF inhibitors like adalimumab, etanercept) or immune cells (e.g., rituximab).

- Targeted Synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs): JAK inhibitors (e.g., tofacitinib).

- Conventional Synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs):

- NSAIDs: For symptomatic relief of pain and inflammation, but do not alter disease progression.

- Corticosteroids: Used for short-term control of flares or as a bridge until DMARDs take effect, due to side effects with long-term use.

- Physical and Occupational Therapy: To maintain joint flexibility, strength, and function, and to adapt to limitations.

- Surgery: May be needed for severe joint damage (e.g., joint replacement, synovectomy).

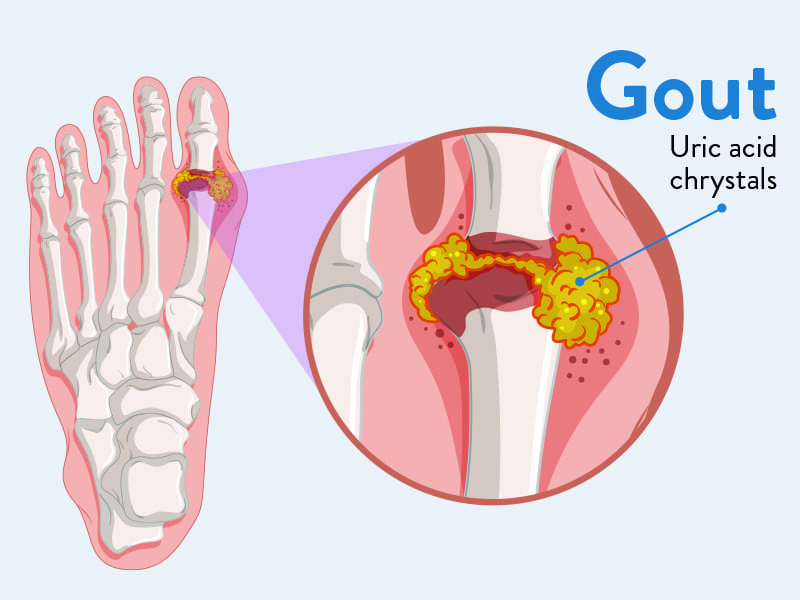

Gout

Gout is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of acute inflammatory arthritis, often affecting a single joint initially. It is caused by the deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in joints, tendons, and surrounding tissues, which triggers a potent inflammatory response.

The underlying biochemical abnormality in gout is hyperuricemia, meaning elevated levels of uric acid in the blood. Uric acid is the end-product of purine metabolism, and its overproduction or underexcretion (or a combination) leads to its accumulation.

Etiology (Causes) and Pathophysiology (Mechanisms of Disease)

The etiology of gout revolves around hyperuricemia, with various factors contributing to its development and the subsequent crystal deposition and inflammation.

A. Role of Hyperuricemia:

- Definition: Serum uric acid levels exceeding 6.8 mg/dL (404 µmol/L) are considered hyperuricemic, as this is the approximate saturation point of uric acid in extracellular fluid at normal physiological temperature and pH. Above this concentration, MSU crystals can precipitate.

- Sources of Uric Acid:

- Endogenous Production (80%): From the breakdown of purines (components of DNA and RNA) in the body's own cells.

- Exogenous Intake (20%): From the metabolism of purines consumed in the diet.

- Balance: Uric acid levels are maintained by a balance between production and excretion (primarily via the kidneys, with some intestinal excretion).

- Causes of Hyperuricemia:

- Underexcretion of Uric Acid (Most Common - ~90% of cases): The kidneys are unable to adequately excrete uric acid. This can be genetic or due to kidney disease, certain medications (e.g., thiazide diuretics, low-dose aspirin), or lead exposure.

- Overproduction of Uric Acid (~10% of cases): Increased purine metabolism due to genetic enzyme defects (e.g., Lesch-Nyhan syndrome), high cell turnover rates (e.g., certain cancers, psoriasis), or excessive purine intake.

B. Role of Diet:

- High-Purine Foods: Consumption of foods rich in purines can increase uric acid levels. Examples include:

- Red meat and organ meats: Liver, kidney, sweetbreads.

- Certain seafood: Anchovies, sardines, mussels, scallops, shrimp.

- Alcohol: Especially beer and spirits, increase uric acid production and reduce its excretion. Wine appears to have less effect.

- Fructose-Sweetened Beverages: High fructose corn syrup can increase uric acid production.

- Dehydration: Can concentrate uric acid in the blood.

C. Role of Genetics:

- Familial Predisposition: A family history of gout is a significant risk factor.

- Genetic Polymorphisms: Variations in genes coding for uric acid transporters in the kidneys (e.g., SLC22A12 which codes for URAT1) can affect uric acid excretion.

D. Role of Renal Function:

- Impaired Kidney Function: Any condition that impairs kidney function (e.g., chronic kidney disease, hypertension, diabetes) can lead to reduced uric acid excretion and thus hyperuricemia.

E. Other Contributing Factors:

- Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome: Strongly associated with hyperuricemia and gout.

- Certain Medications: Diuretics (thiazides and loop), low-dose aspirin, cyclosporine, niacin.

- Surgery/Trauma: Can precipitate acute attacks.

- Hypothyroidism: Can reduce renal excretion of uric acid.

Pathophysiology: The Acute Gout Attack

- Crystal Formation: In hyperuricemic individuals, MSU crystals can precipitate out of solution and deposit in cooler, less vascular tissues, particularly in joints, cartilage, and periarticular structures.

- Crystal Shedding and Immune Response: For an acute attack to occur, these deposited crystals must "shed" into the joint fluid. Once free in the joint space, MSU crystals act as danger signals to the immune system.

- Inflammasome Activation: The crystals are phagocytosed (engulfed) by local macrophages and synovial cells. This process activates the NLRP3 inflammasome, a multi-protein complex within these cells.

- Cytokine Release: Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome leads to the cleavage and release of potent pro-inflammatory cytokines, especially Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β).

- Inflammatory Cascade: IL-1β initiates a rapid and intense inflammatory cascade:

- Recruitment of neutrophils, monocytes, and other inflammatory cells to the joint.

- Release of proteases, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and free radicals, which cause the characteristic pain, swelling, redness, and heat.

- Vascular dilation and increased capillary permeability.

- Self-Limiting Nature: Untreated acute attacks typically last for 7-10 days and then spontaneously resolve. This is partly due to the removal of crystals by phagocytes, production of anti-inflammatory mediators (e.g., TGF-β, IL-10), and coating of crystals by proteins, making them less immunostimulatory.

Pathophysiology: Chronic Tophaceous Gout

- With recurrent, untreated acute attacks, MSU crystals can accumulate over time, forming large, palpable deposits called tophi.

- Tophi can develop in various tissues, including joints, bursae (e.g., olecranon, prepatellar), ear helices, fingertips, Achilles tendons, and even internal organs (e.g., kidneys).

- These tophi cause chronic inflammation, progressive joint destruction, bone erosion, and permanent deformity.

Clinical Manifestations (Signs and Symptoms)

Gout typically progresses through several stages: asymptomatic hyperuricemia, acute gouty arthritis, intercritical gout (periods between attacks), and chronic tophaceous gout.

A. Acute Gouty Arthritis:

- Sudden Onset: Attacks typically start very suddenly, often at night, with rapidly escalating pain.

- Excruciating Pain: The pain is usually described as excruciating, intense, and often incapacitating. Even the touch of a bedsheet can be unbearable.

- Monoarticular (Initially): Affects a single joint in about 80-90% of initial attacks.

- Podagra: The classic presentation is inflammation of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint of the big toe, occurring in about 50% of initial attacks.

- Other Affected Joints: Ankle, knee, wrist, fingers, elbow (olecranon bursa).

- Signs of Inflammation: The affected joint becomes extremely red, hot, swollen, and exquisitely tender. It mimics a severe infection.

- Systemic Symptoms: May include low-grade fever, chills, and malaise.

- Self-Limiting: Untreated attacks usually resolve spontaneously within 7-10 days.

B. Intercritical Gout:

- The symptom-free periods between acute attacks. During this time, MSU crystals are still present in the joints and hyperuricemia persists, making future attacks likely.

C. Chronic Tophaceous Gout:

- Develops in individuals with long-standing, untreated hyperuricemia and recurrent attacks.

- Tophi: Hard, painless (unless inflamed or infected) nodules formed by MSU crystal deposits. Commonly found in:

- Ear helices

- Fingers and toes (especially around joints)

- Olecranon bursa (elbow)

- Prepatellar bursa (knee)

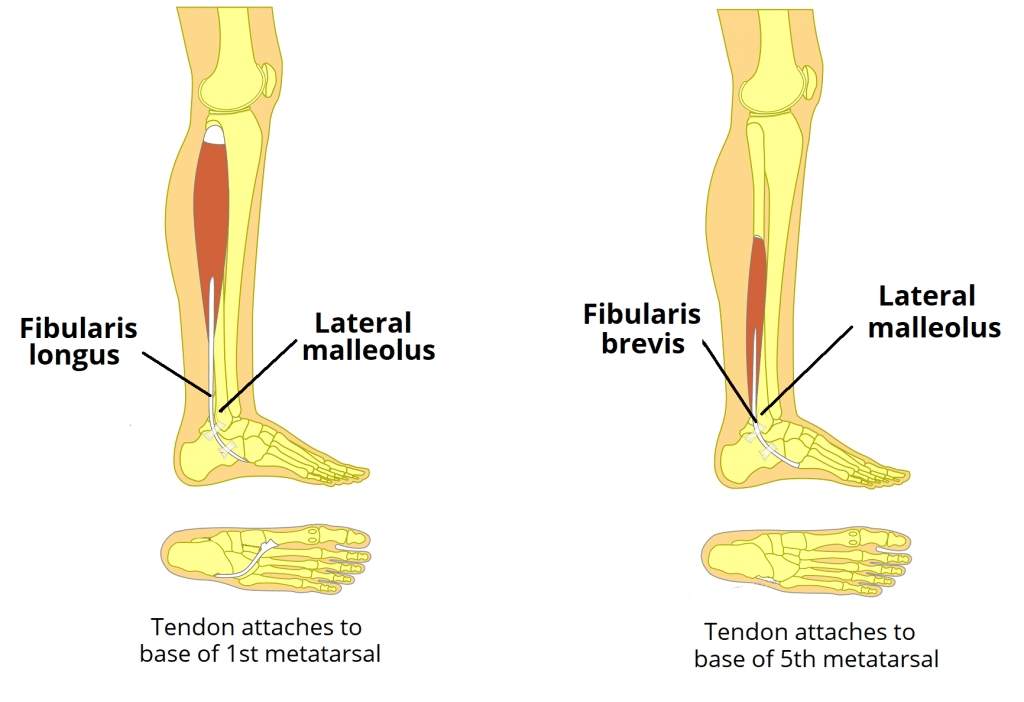

- Achilles tendon

- Chronic Pain and Swelling: Persistent low-grade pain and swelling in affected joints.

- Joint Damage and Deformity: Tophi can cause significant joint destruction, leading to chronic arthritis, pain, stiffness, limited range of motion, and severe joint deformities.

- Skin Ulceration: Tophi can sometimes ulcerate, discharging a chalky, white material (MSU crystals).

D. Associated Complications:

- Uric Acid Nephrolithiasis (Kidney Stones): Elevated uric acid can precipitate in the kidneys, forming kidney stones.

- Urate Nephropathy: Chronic kidney disease caused by uric acid deposits in the kidney tissue.

- Cardiovascular Disease: Gout is often associated with other components of metabolic syndrome (obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance), increasing the risk of heart disease and stroke.

Diagnosis: The definitive diagnosis of gout is made by aspiration of synovial fluid from an affected joint and identification of negatively birefringent, needle-shaped MSU crystals under a polarized light microscope.

- Clinical Suspicion: Based on characteristic acute monoarthritis, especially podagra.

- Serum Uric Acid: Elevated, but can be normal or even low during an acute attack (due to inflammatory effects). A normal uric acid level does not rule out gout during an acute flare.

- Imaging: X-rays are often normal in early attacks but may show characteristic "punched-out" erosions with overhanging edges ("rat-bite" erosions) in chronic tophaceous gout. Ultrasound can detect MSU deposits.

Treatment Principles:

Treatment involves managing acute attacks and preventing future attacks by lowering uric acid levels.

- Acute Attack Management:

- NSAIDs: High-dose NSAIDs (e.g., indomethacin, naproxen).

Colchicine: Effective if started early in an attack.- Corticosteroids: Oral or intra-articular injections.

- Urate-Lowering Therapy (ULT) for Prevention:

- Allopurinol: Most common first-line agent, a xanthine oxidase inhibitor that reduces uric acid production.

- Febuxostat: Another xanthine oxidase inhibitor.

- Probenecid: A uricosuric agent that increases renal excretion of uric acid (used in underexcreters).

- Pegloticase: An intravenous enzyme that metabolizes uric acid, used for severe, refractory chronic tophaceous gout.

Goal: To maintain serum uric acid levels below 6 mg/dL (or even lower for severe tophaceous gout) to prevent crystal formation and dissolve existing crystals. ULT is typically initiated after an acute attack has resolved, sometimes with colchicine prophylaxis to prevent flares during initiation.

3. Lifestyle Modifications:

- Dietary changes: Avoid high-purine foods, alcohol (especially beer), and fructose-sweetened drinks.

- Weight loss.

- Hydration.

https://doctorsrevisionuganda.com | Whatsapp: 0726113908

Common Disorders of Tissues

Test your knowledge with these 20 questions.

Disorders of Tissues Quiz

Question 1/20

Quiz Complete!

Here are your results, .

Your Score

18/20

90%

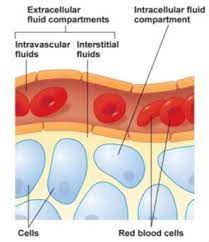

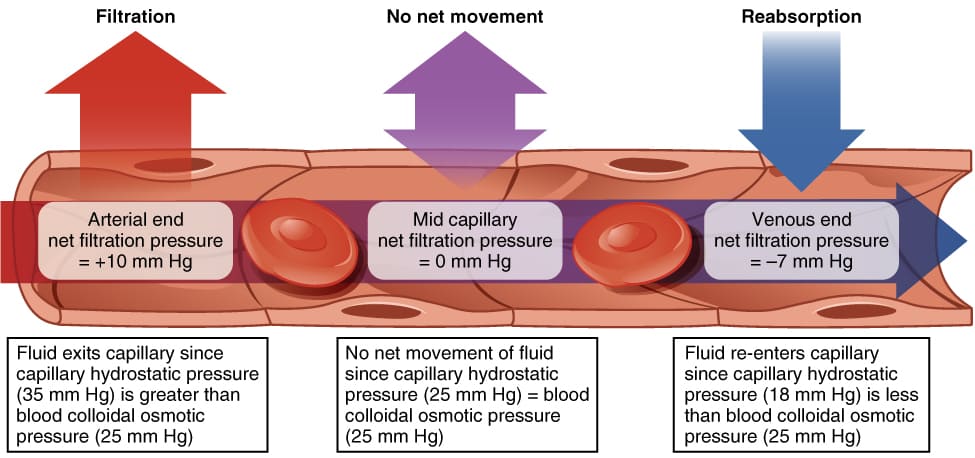

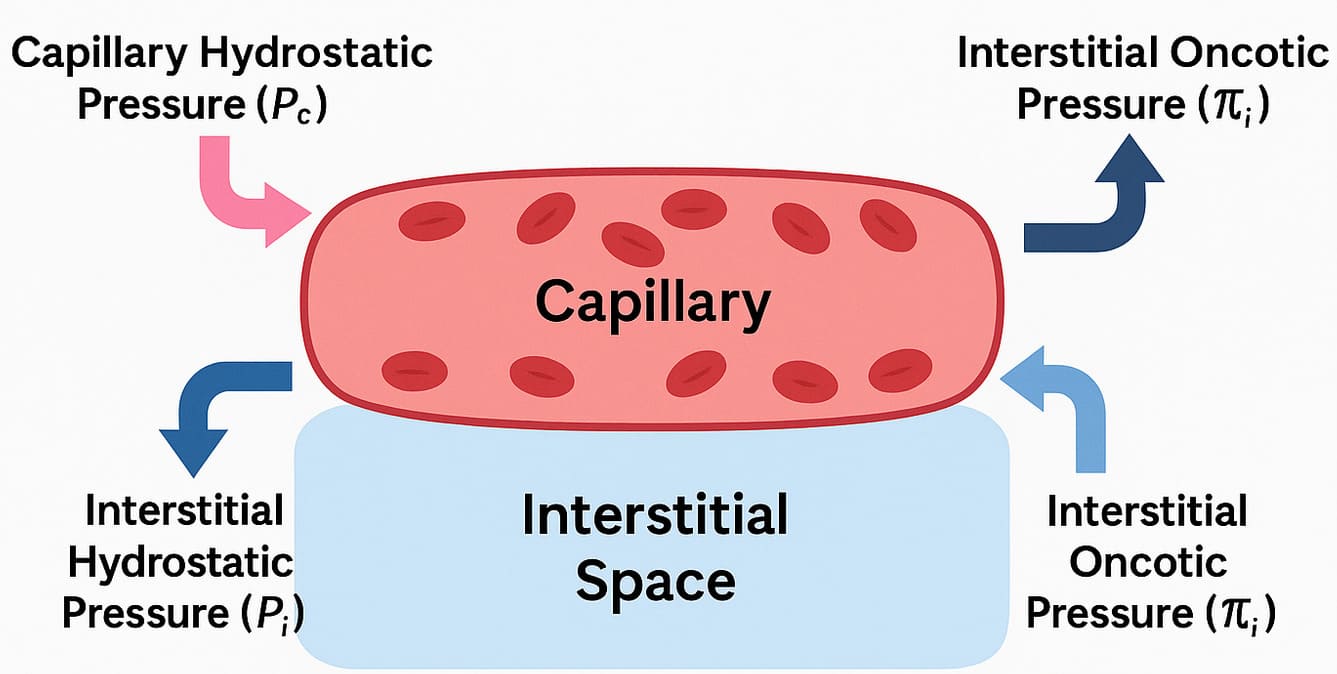

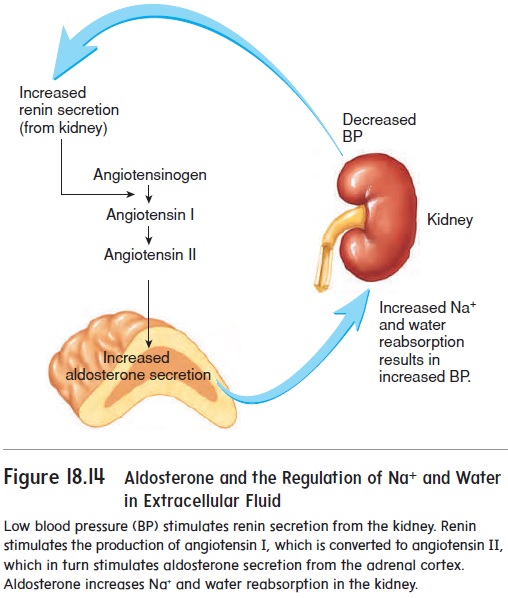

Starling Forces - The Drivers of Capillary Exchange:

Starling Forces - The Drivers of Capillary Exchange:

Superficial Layer

Superficial Layer