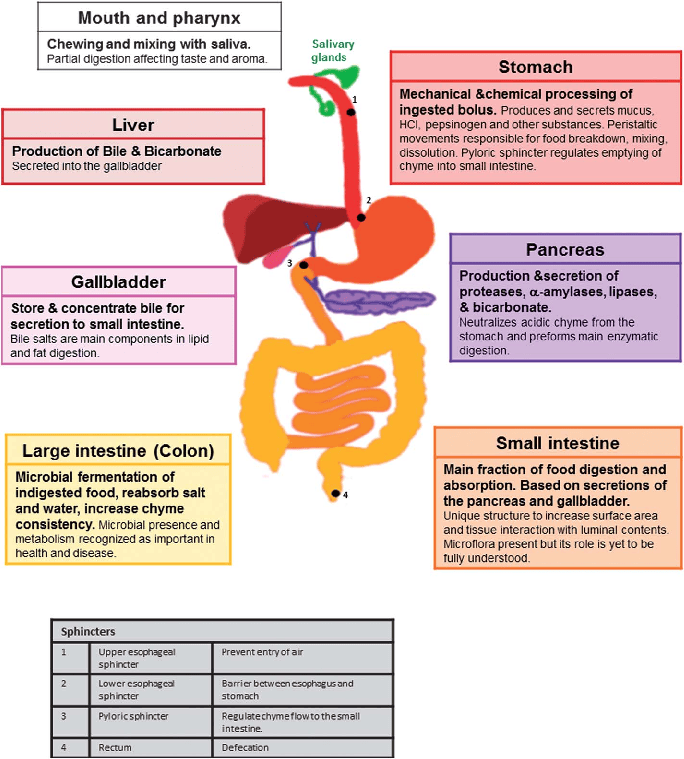

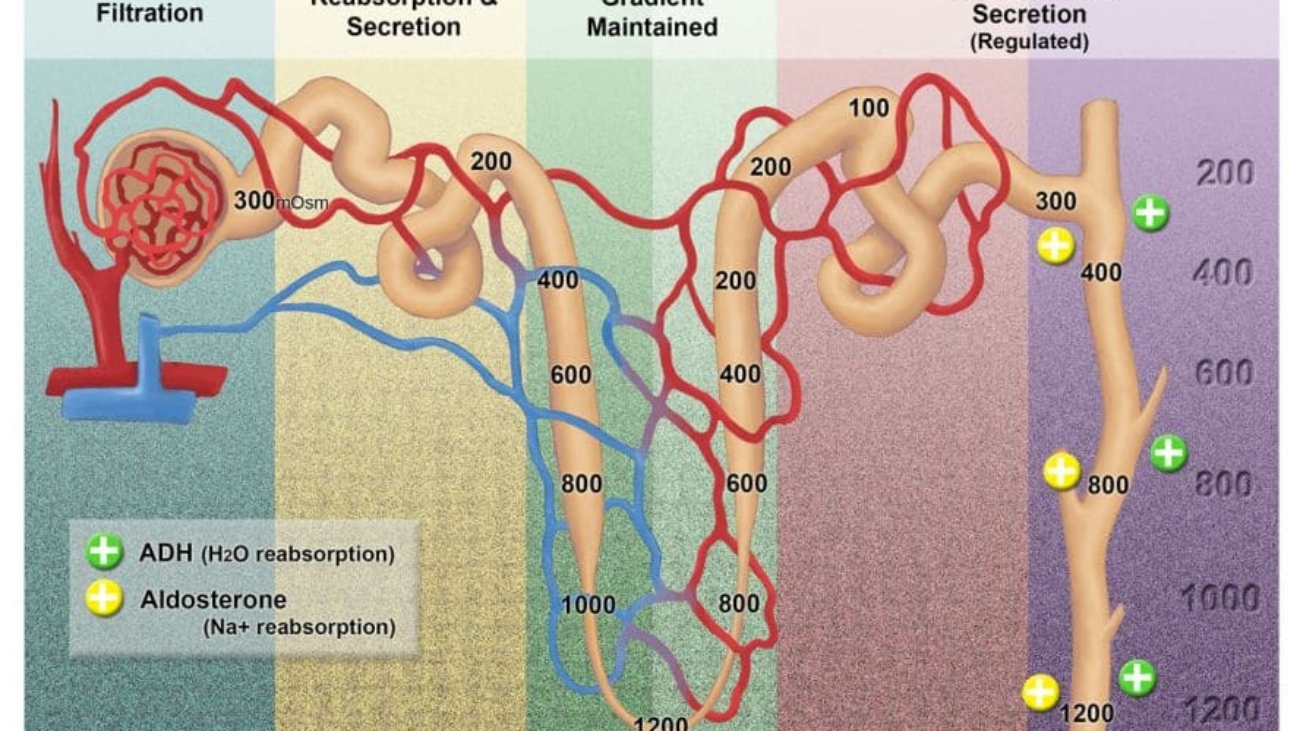

Stomach & Intestines

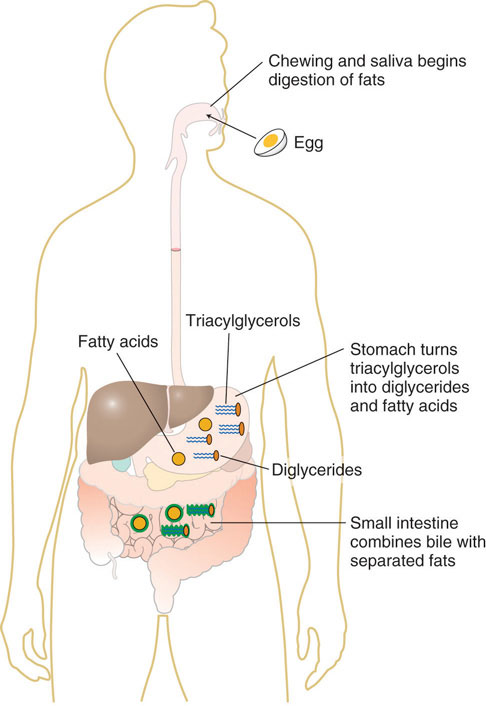

Stomach

The stomach is a dilated, J-shaped organ of the alimentary canal, situated between the esophagus and the duodenum.

Functions

- Storage of food: It acts as a temporary reservoir for ingested food.

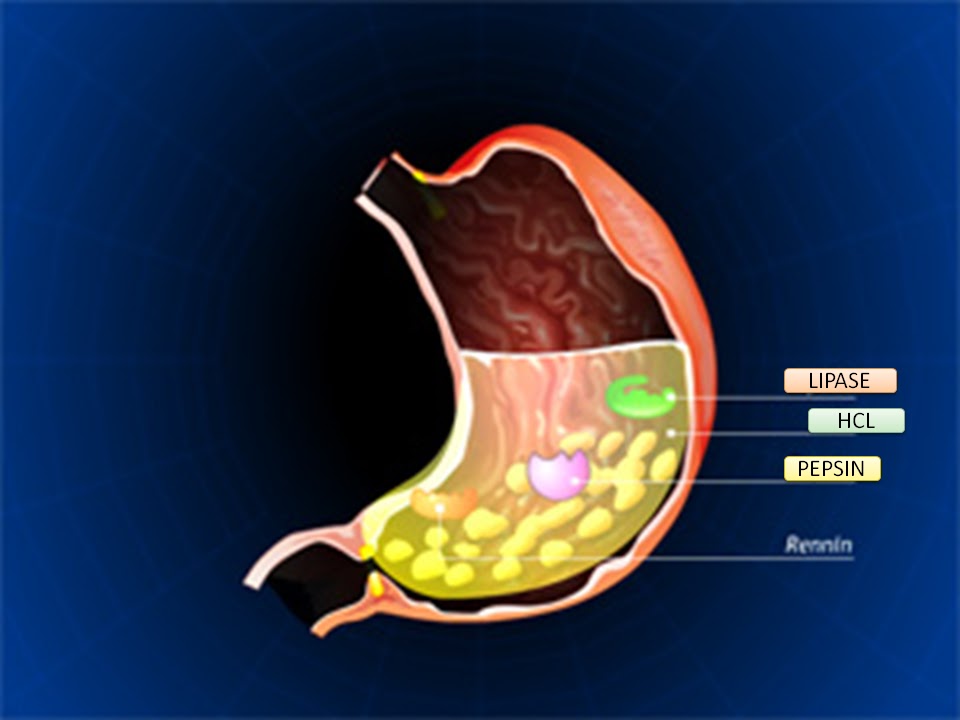

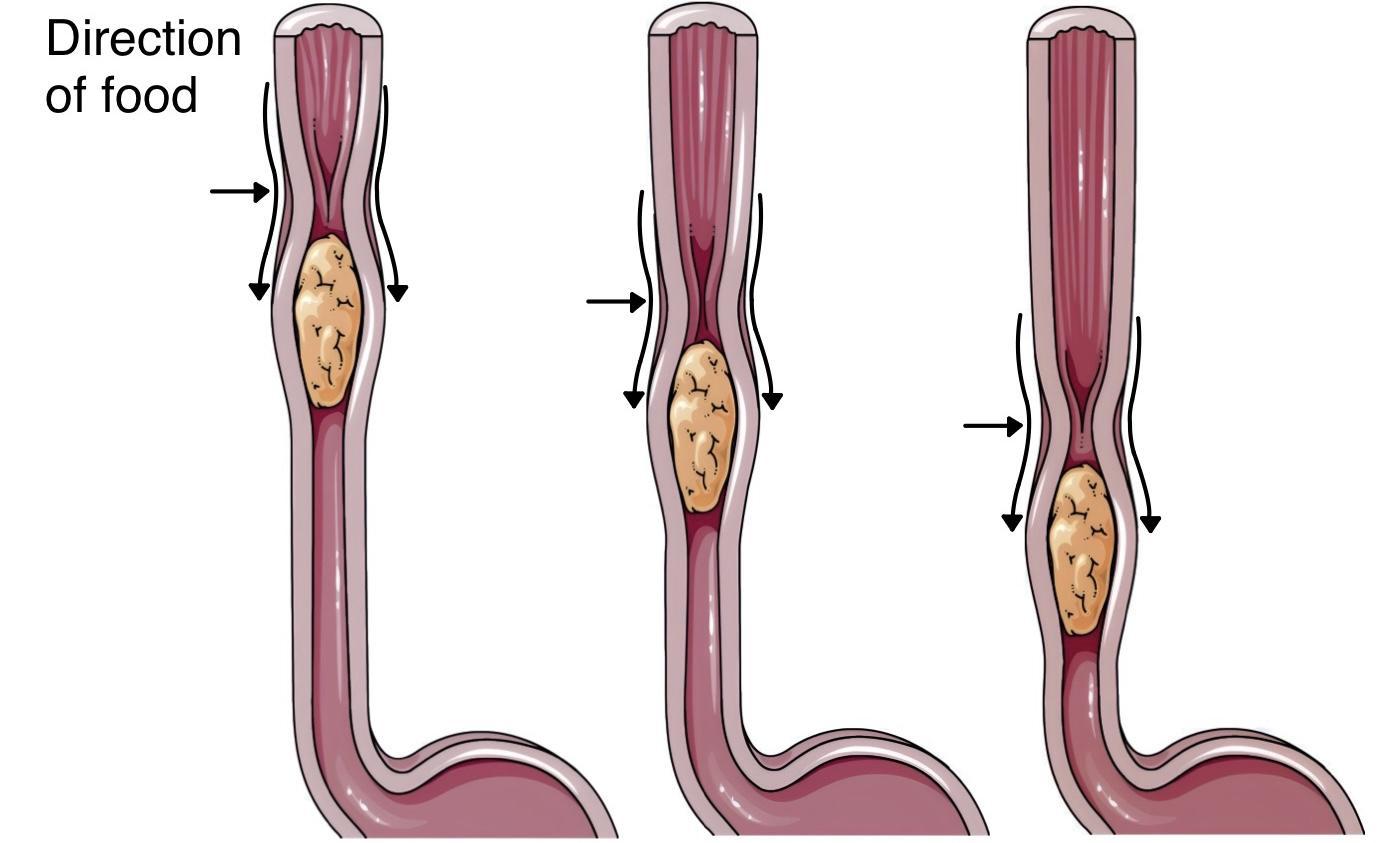

- Mixing and mechanical digestion: It churns food with gastric juices to form chyme.

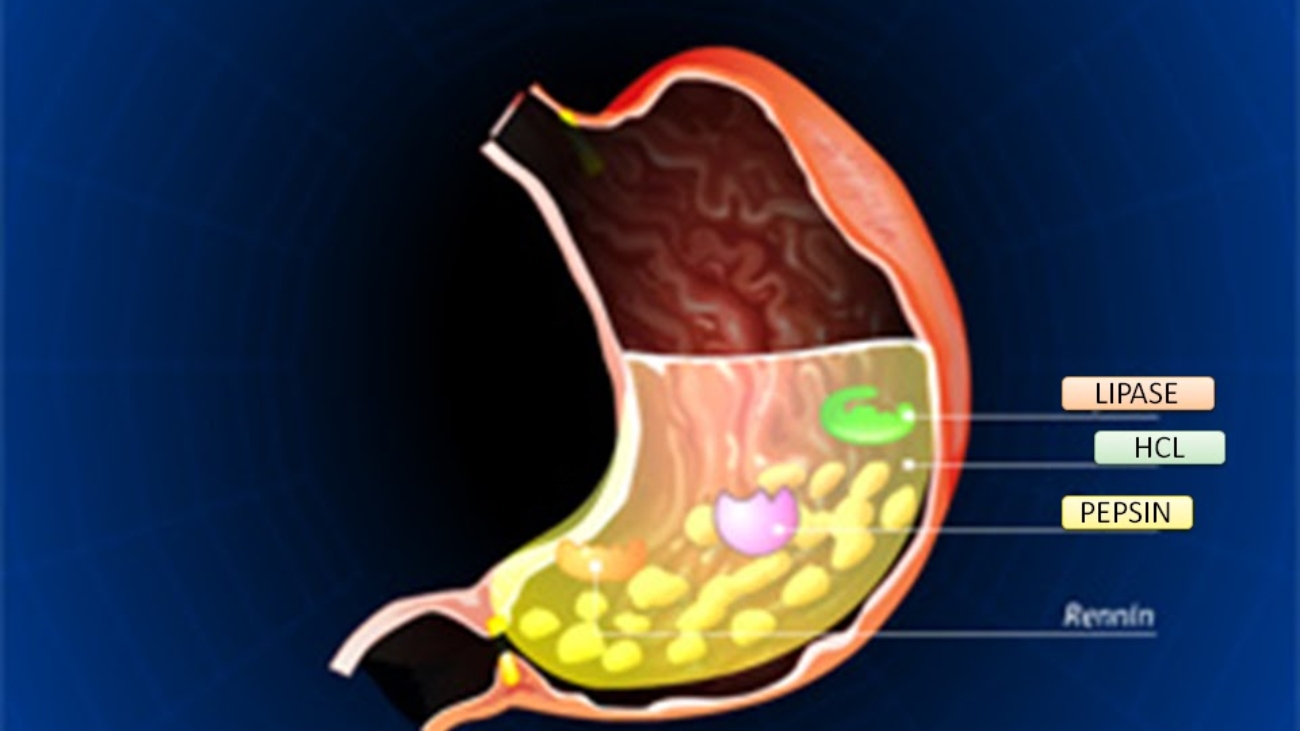

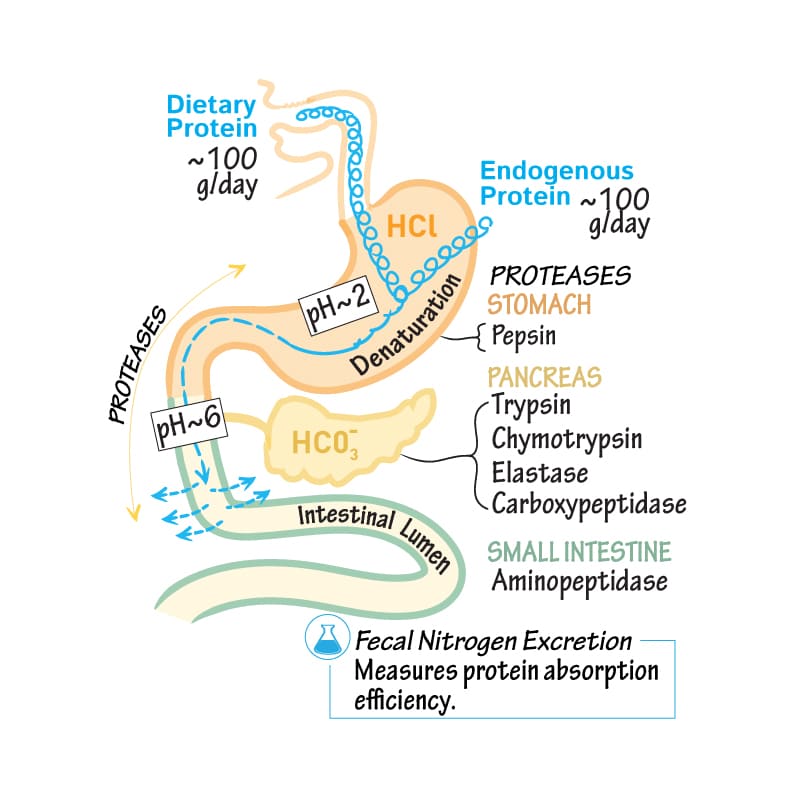

- Chemical digestion: Gastric juices (containing hydrochloric acid and enzymes like pepsin) initiate protein digestion.

- Controlled release: Regulates the slow release of chyme into the duodenum for further digestion and absorption.

General Characteristics

- Capacity: The total capacity of the stomach is approximately 1500 ml.

- Shape and Position:

- Its position and shape vary significantly among individuals and with posture and respiration. In short and obese individuals, it tends to be high and more transverse. In tall and thin individuals, it is often elongated and vertical.

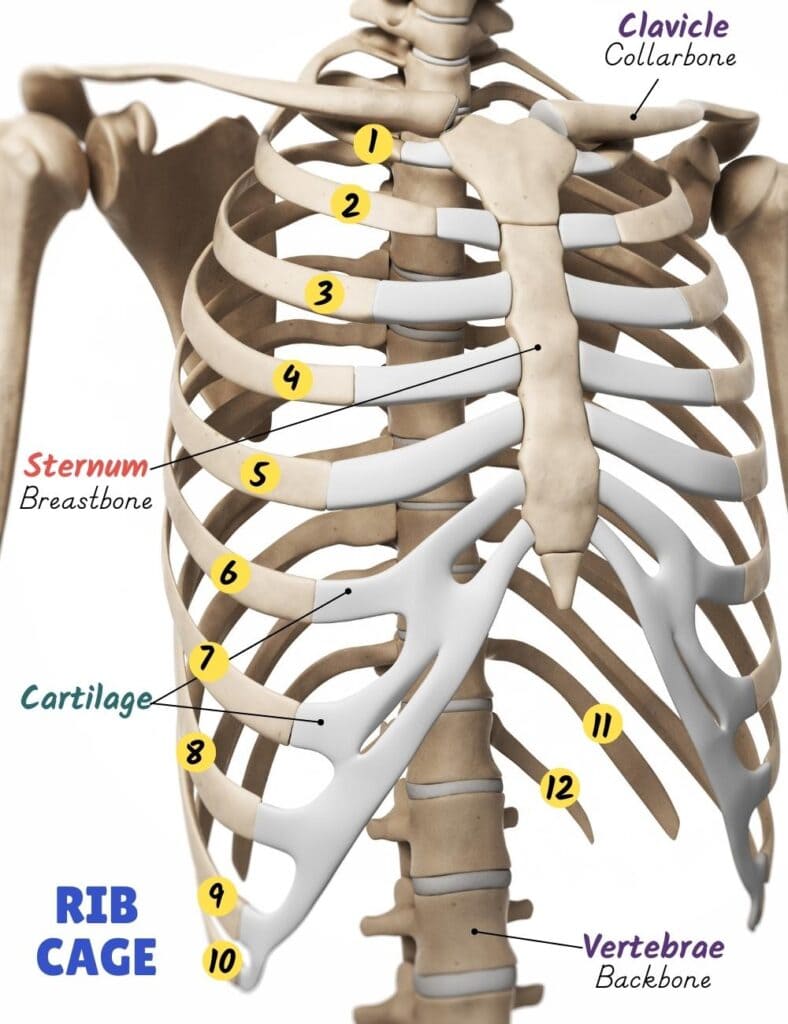

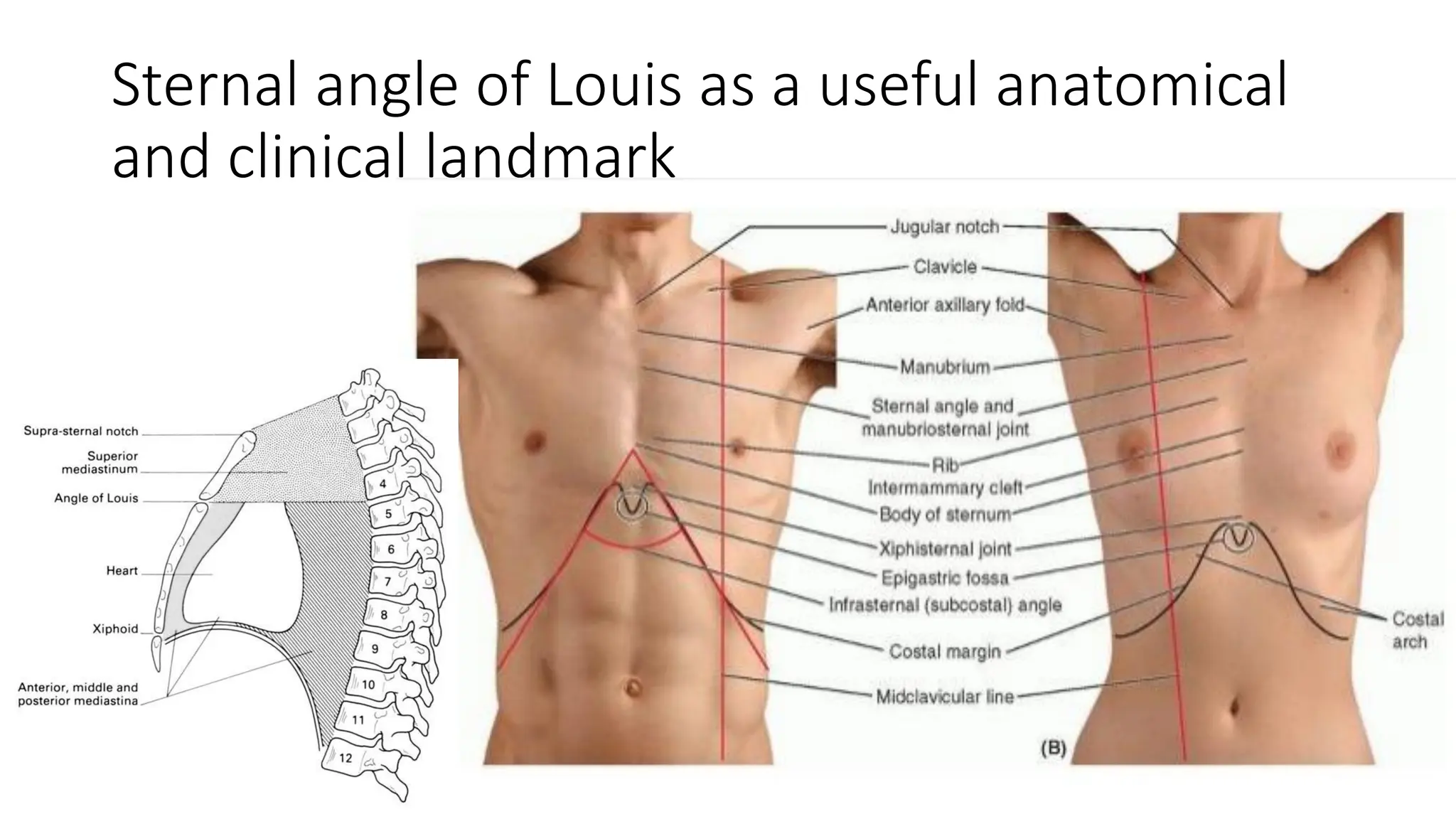

- It typically occupies the epigastric and umbilical regions of the abdomen and is partly covered by the costal diaphragm and the lower ribs.

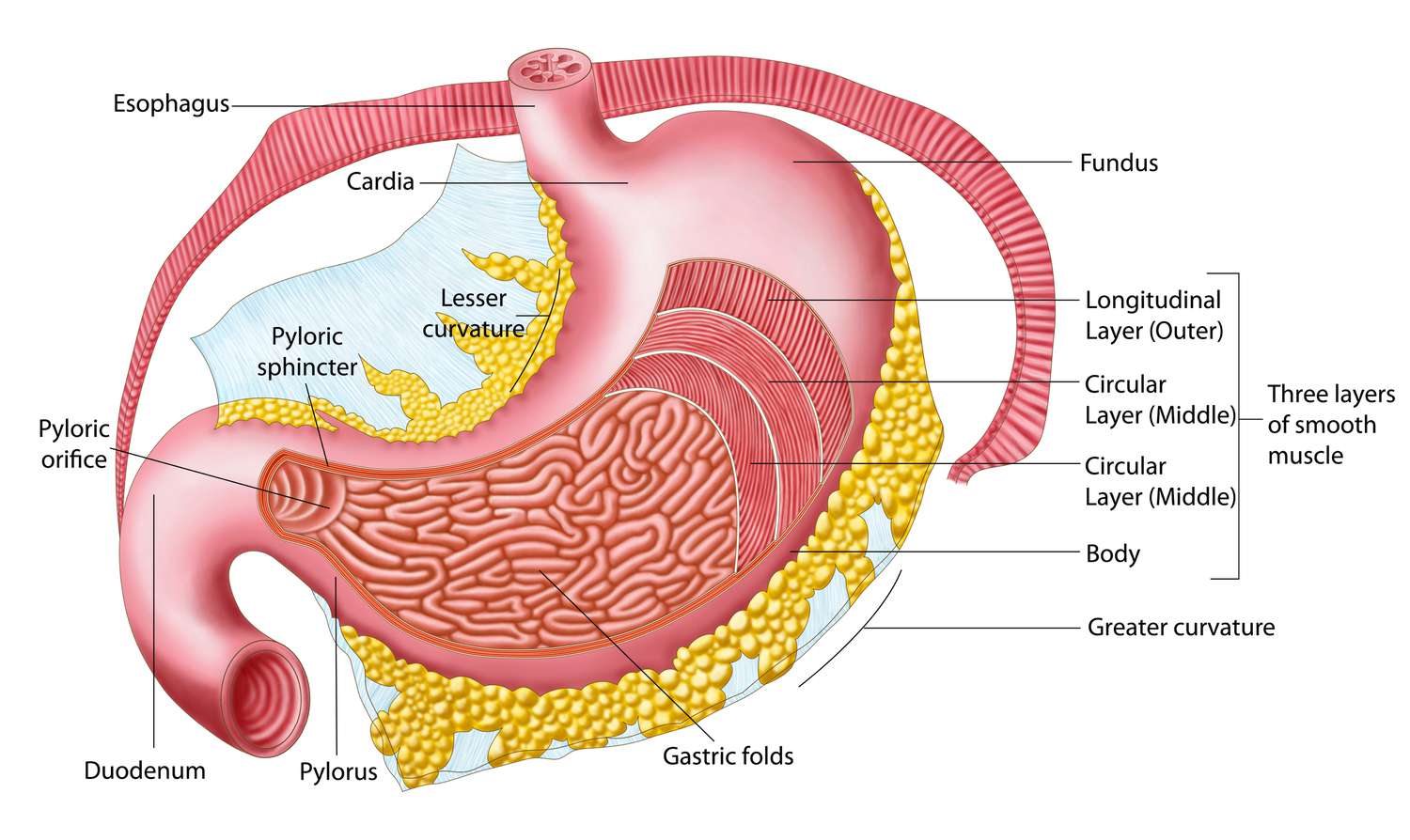

General Structure

The stomach has two surfaces, two apertures (orifices), and two curvatures.

- Surfaces: Anterior surface, Posterior surface.

- Orifices (Apertures):

- Cardia: The opening from the esophagus into the stomach.

- Pylorus: The opening from the stomach into the duodenum.

- Curvatures:

- Lesser curvature: The shorter, concave, right border of the stomach.

- Greater curvature: The longer, convex, left and inferior border of the stomach.

Specific Features:

Cardia (Cardiac Orifice)

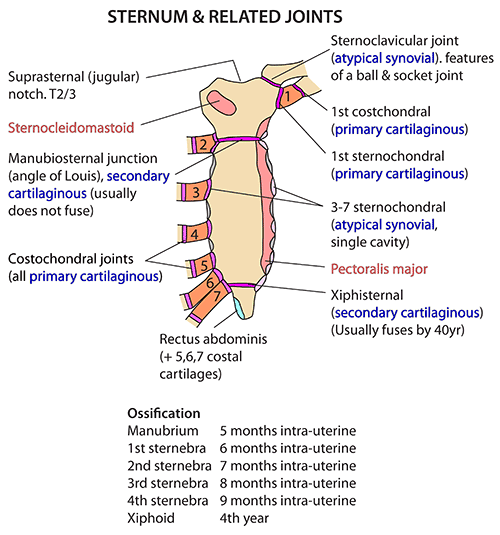

- Located at the esophagogastric junction.

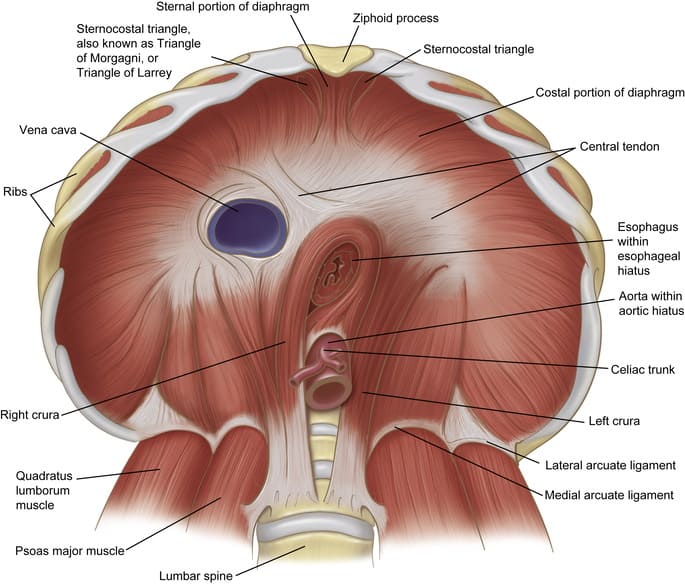

- There is no anatomical sphincter in the traditional sense. Instead, a physiological sphincter mechanism is formed by the circular muscle layer of the distal esophagus and stomach, the acute angle of His (where the esophagus joins the stomach), and the diaphragmatic crus.

- This physiological sphincter relaxes during swallowing to allow food entry and closes afterward to prevent gastroesophageal reflux (regurgitation) of gastric contents back into the esophagus.

Pylorus

- The distal opening of the stomach into the duodenum, located at the gastroduodenal junction.

Lesser Curvature

- Located on the right margin of the stomach.

- Serves as the attachment site for the lesser omentum.

- The angular incisure (incisura angularis) is a constant notch on the lesser curvature, marking the junction between the body and the pyloric part of the stomach.

Greater Curvature

- Located on the left margin and inferior border of the stomach.

- Provides attachment for the gastrosplenic ligament (connecting to the spleen) and the greater omentum (which extends inferiorly, folds back, and attaches to the transverse colon).

- Anterior Surface: Covered by the peritoneum. The left vagus nerve forms the anterior vagal trunk and predominantly supplies the anterior surface of the stomach.

- Posterior Surface: Also covered by the peritoneum. The right vagus nerve forms the posterior vagal trunk and predominantly supplies the posterior surface of the stomach.

Parts of the Stomach

The stomach is typically divided into four main parts:

- Cardia: The region immediately surrounding the cardiac orifice.

- Fundus: The dome-shaped part that projects superiorly and to the left of the cardia. It often contains gas.

- Body: The main part of the stomach, extending from the cardia/fundus to the angular incisure on the lesser curvature.

- Pylorus (Pyloric Part): The tubular distal part of the stomach connecting it to the duodenum. It is further divided into:

- Pyloric Antrum: Wider, more proximal part.

- Pyloric Canal: Narrower, distal part.

- Pyloric Sphincter: A thickened ring of circular smooth muscle at the gastroduodenal junction. It controls the discharge of chyme from the stomach into the duodenum. The pylorus typically lies on the transpyloric plane (L1).

Peritoneal Attachments (Omenta):

- Lesser Omentum: A two-layered fold of peritoneum that extends from the porta hepatis (on the liver) to the lesser curvature of the stomach and the superior part of the duodenum. It is further divided into:

- Hepatogastric ligament: From the liver to the lesser curvature of the stomach.

- Hepatoduodenal ligament: From the liver to the superior part of the duodenum. This is clinically very important as it contains the portal triad: the common bile duct, the proper hepatic artery, and the hepatic portal vein.

- Greater Omentum: A large, apron-like fold of peritoneum that hangs down from the greater curvature of the stomach and covers the intestines. It contains varying amounts of fat.

- Gastrosplenic Omentum (Ligament): Connects the greater curvature of the stomach to the hilum of the spleen.

Mucous Membrane of the Stomach:

The internal lining of the stomach is thrown into numerous folds called rugae. These folds allow the stomach to expand significantly when filled with food and flatten out as it distends.

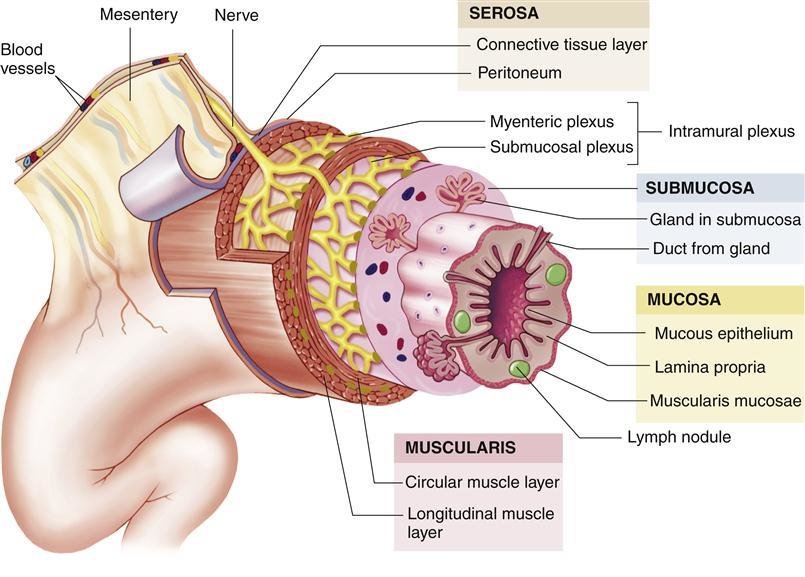

Muscle Layer of the Stomach:

The muscularis externa of the stomach is unique among the alimentary canal because it has three layers of smooth muscle, which contribute to its powerful churning action:

- Outer Longitudinal Layer: Primarily present along the curvatures (lesser and greater).

- Middle Circular Layer: Surrounds the entire stomach but is particularly prominent at the pylorus (forming the pyloric sphincter) and cardia.

- Innermost Oblique Layer: Found mainly in the body and fundus, allowing for a unique churning motion.

Peritoneum of the Stomach: The stomach is almost entirely intraperitoneal, meaning it is nearly completely covered by visceral peritoneum. The peritoneum leaves the stomach to form the various omenta and ligaments (lesser omentum, greater omentum, gastrosplenic omentum).

Relations of the Stomach

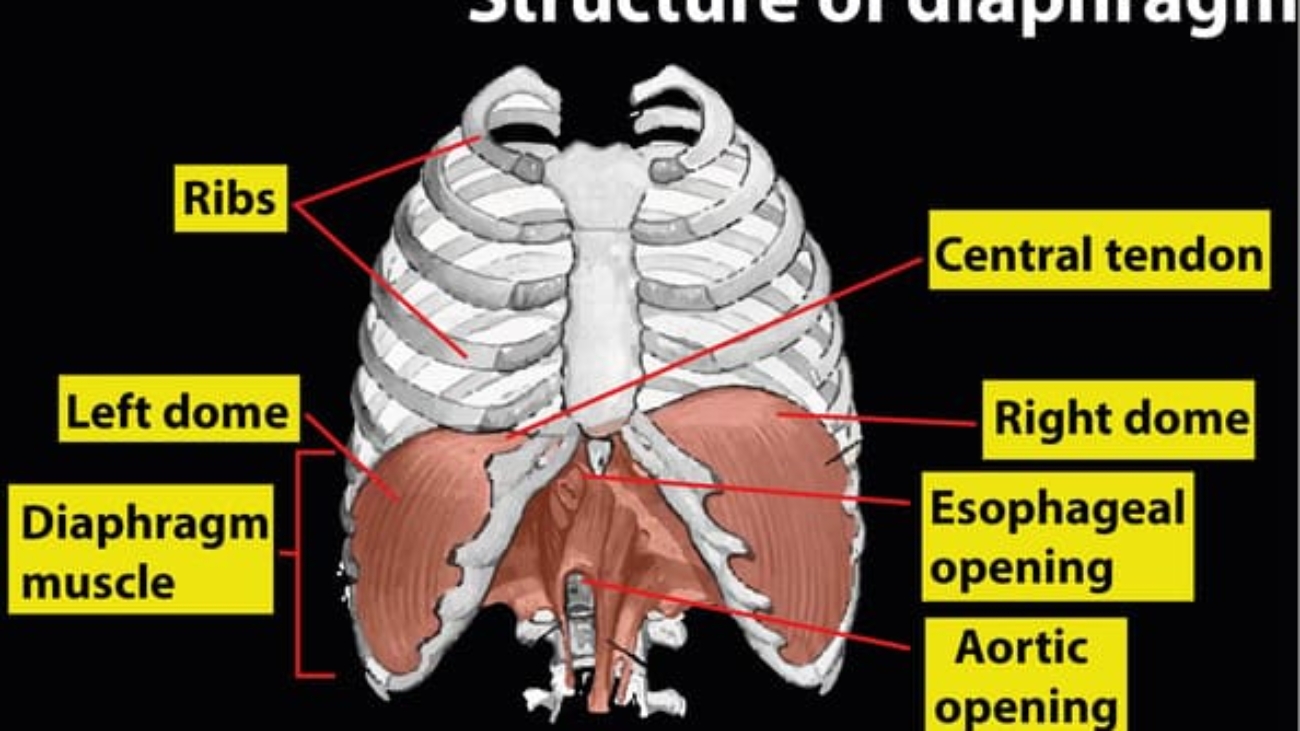

Anteriorly

- Anterior abdominal wall

- Costal margin

- Left lobe of the liver

- Left pleura and lung (superiorly)

- Diaphragm

Posteriorly (Stomach Bed)

Separated by the lesser sac (omental bursa):

- Diaphragm (posteriorly, superiorly)

- Spleen (laterally)

- Splenic artery (superior border of the pancreas)

- Left kidney

- Left suprarenal gland

- Pancreas

- Transverse mesocolon and transverse colon

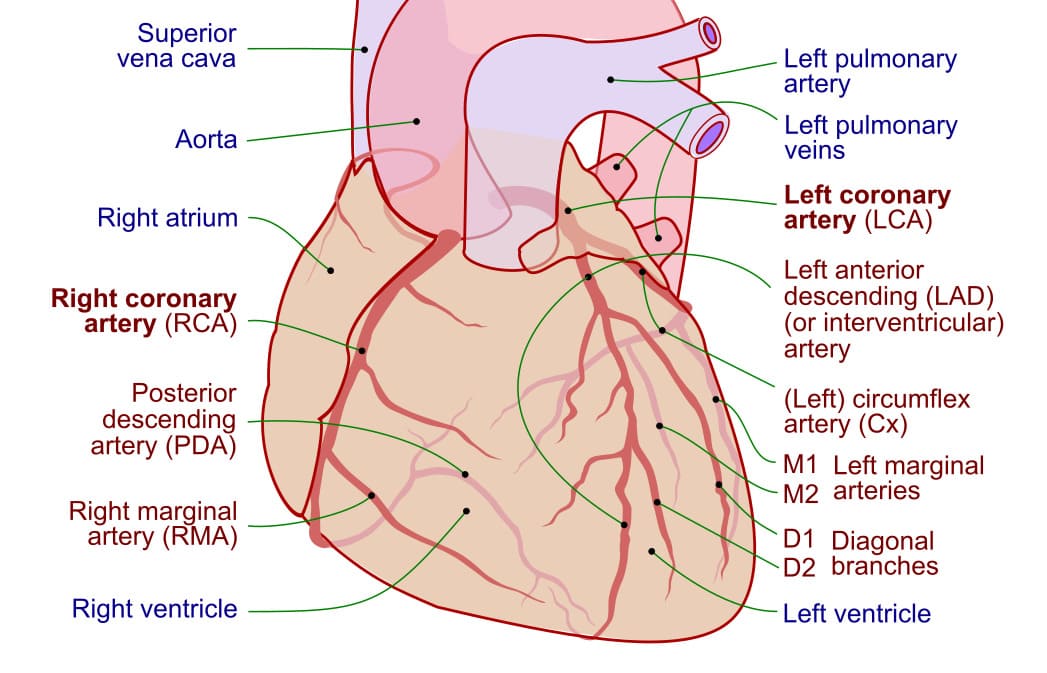

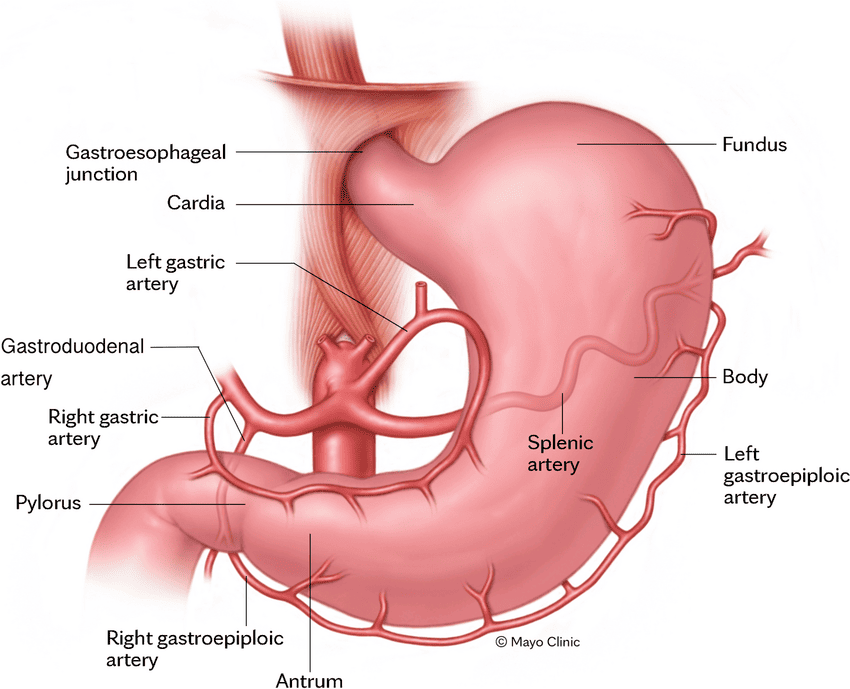

Blood Supply of the Stomach

The stomach has a rich arterial supply from branches of the celiac trunk, ensuring robust collateral circulation.

Arterial Supply

- Lesser Curvature:

- Left Gastric Artery: Direct branch of the celiac trunk. Supplies the upper part of the lesser curvature and the abdominal esophagus.

- Right Gastric Artery: A branch of the proper hepatic artery (which comes from the common hepatic artery, a celiac trunk branch). Supplies the lower part of the lesser curvature.

- Greater Curvature:

- Left Gastro-omental (Gastroepiploic) Artery: A branch of the splenic artery. Supplies the upper part of the greater curvature.

- Right Gastro-omental (Gastroepiploic) Artery: A branch of the gastroduodenal artery (which comes from the common hepatic artery). Supplies the lower part of the greater curvature.

- Fundus:

- Short Gastric Arteries (5-7 branches): Direct branches of the splenic artery. Supply the fundus of the stomach.

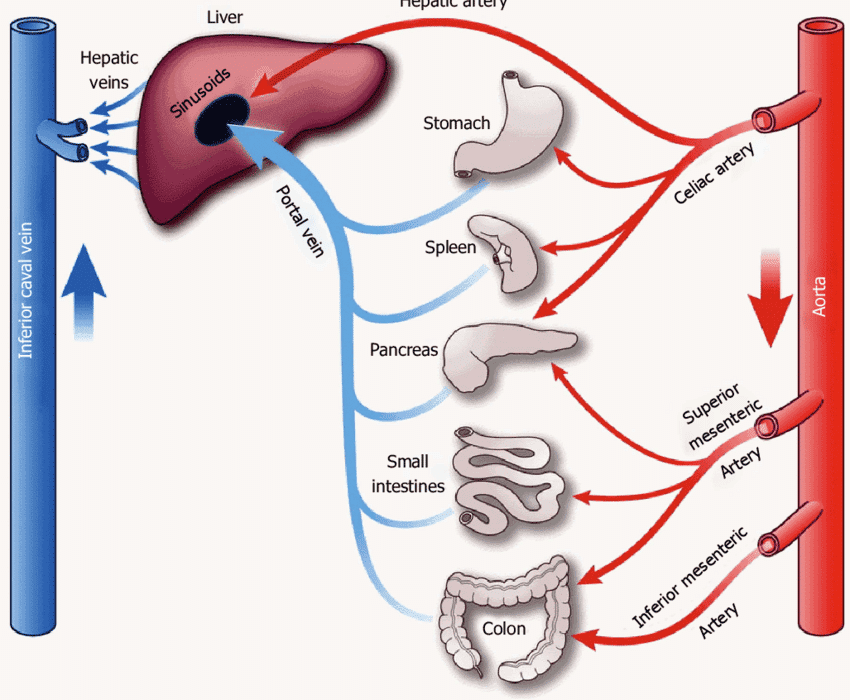

Venous Drainage

The veins of the stomach generally follow the arteries and drain into the portal venous system.

- Left and Right Gastric Veins: Drain the lesser curvature directly into the hepatic portal vein.

- Left Gastro-omental Vein: Drains the greater curvature into the splenic vein.

- Right Gastro-omental Vein: Drains the greater curvature into the superior mesenteric vein.

- Short Gastric Veins: Drain the fundus into the splenic vein.

Lymphatic Drainage: Lymphatic vessels generally follow the arterial supply and drain into regional lymph nodes, eventually leading to the celiac lymph nodes around the celiac trunk.

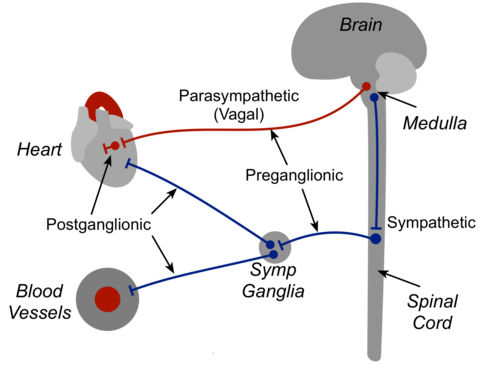

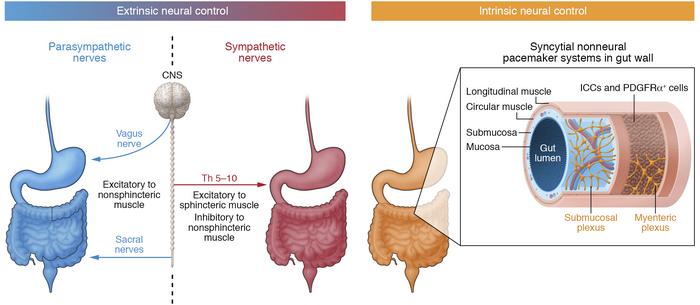

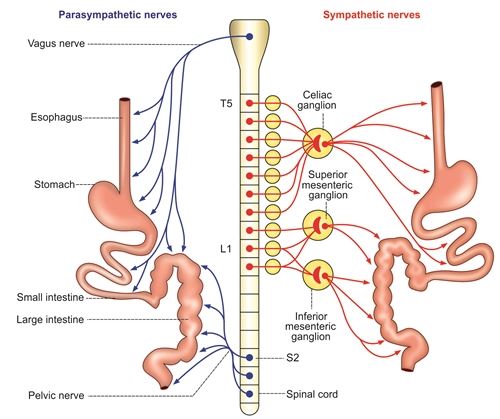

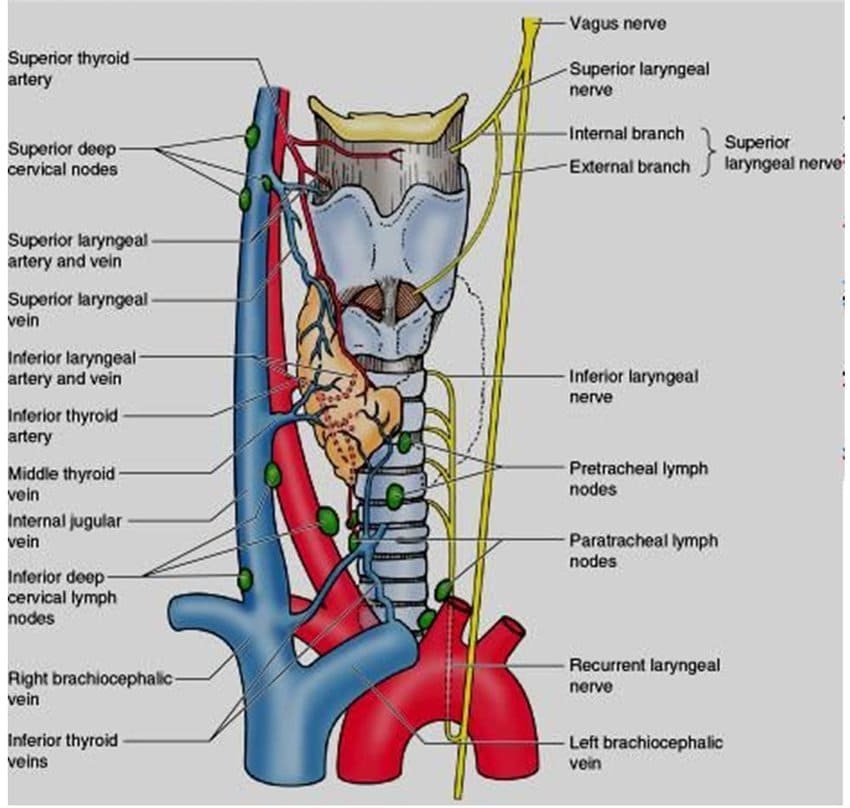

Nerve Supply:

- Parasympathetic Innervation: Primarily from the vagus nerves. The left vagus forms the anterior vagal trunk, and the right vagus forms the posterior vagal trunk. They increase gastric motility and glandular secretion.

- Sympathetic Innervation: From the celiac plexus, originating from spinal cord segments T6-T9. They generally inhibit gastric motility and secretion, and mediate pain.

Clinical Notes:

- Trauma to the Stomach: The stomach is relatively mobile and protected by the rib cage, making blunt trauma less likely to cause injury unless severe. However, penetrating injuries (e.g., stab wounds, gunshot wounds) can lead to perforation and leakage of gastric contents into the peritoneal cavity, causing peritonitis, a serious inflammatory condition.

- Gastric Ulcers: These are open sores that develop on the gastric mucosa. They are common at the pylorus and lesser curvature, areas where the mucosa is exposed to acidic gastric contents (despite the note stating "alkaline producing mucosa," these areas are indeed exposed to acid and are common ulcer sites; the pyloric region, however, also has some bicarbonate secretion). Ulcers can perforate the stomach wall, leading to peritonitis.

- Gastric Pain: Pain originating from the stomach (e.g., from ulcers, gastritis) is typically referred to the epigastrium (upper central abdomen) via the sympathetic nerves.

- Cancer of the Stomach: Gastric cancer can spread to regional lymph nodes. Surgical treatment often involves removing the stomach (gastrectomy) and associated regional lymph nodes, and sometimes neighboring structures, depending on the extent of spread.

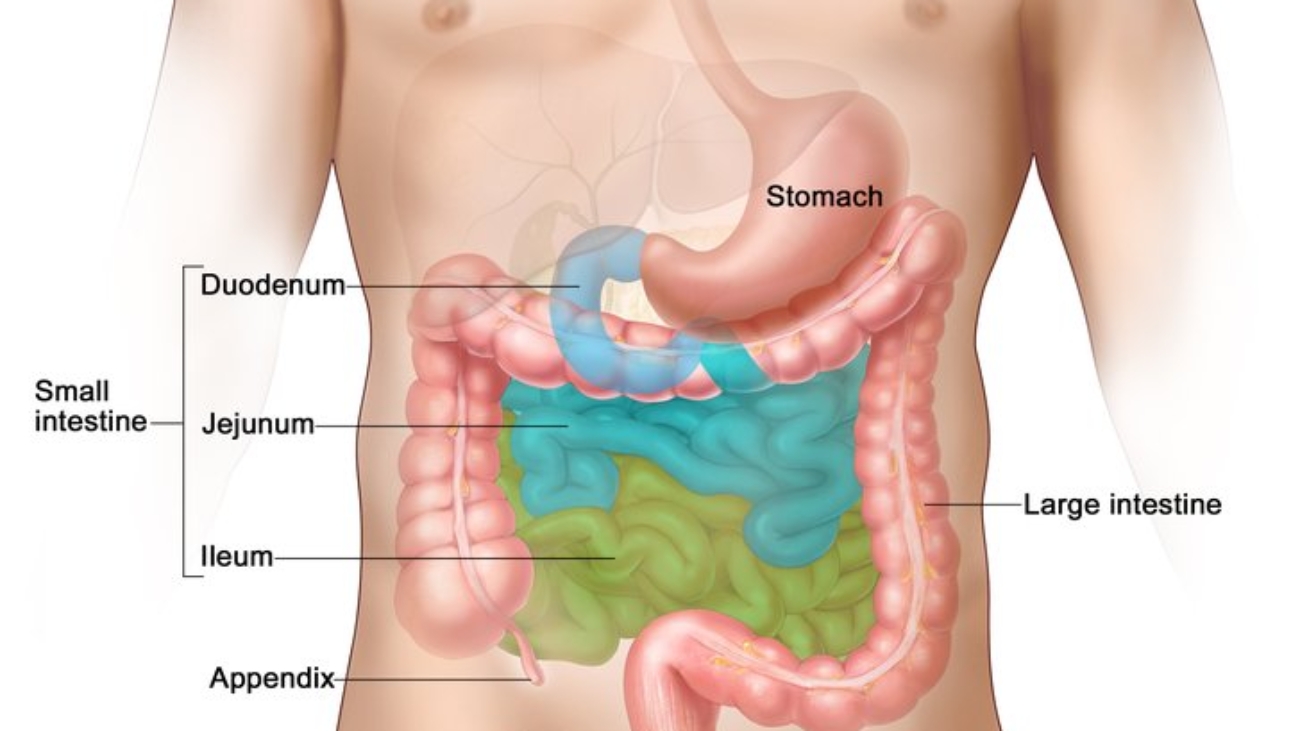

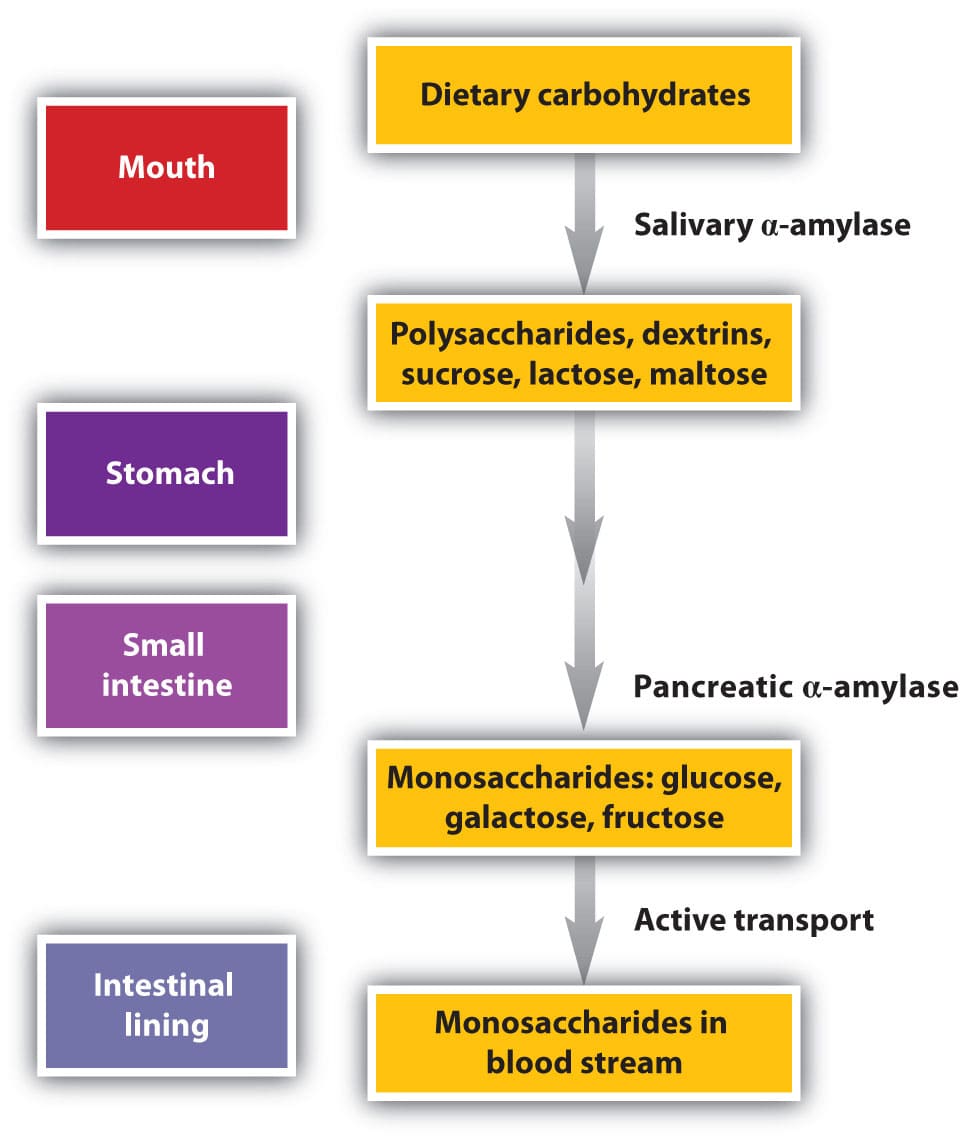

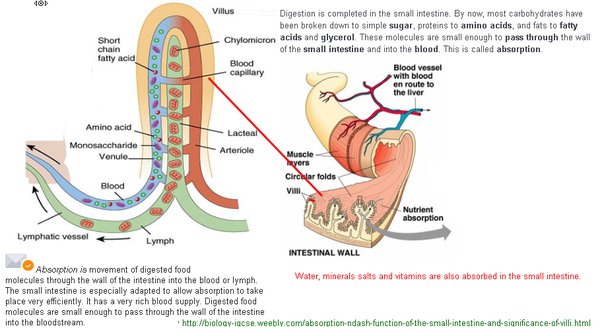

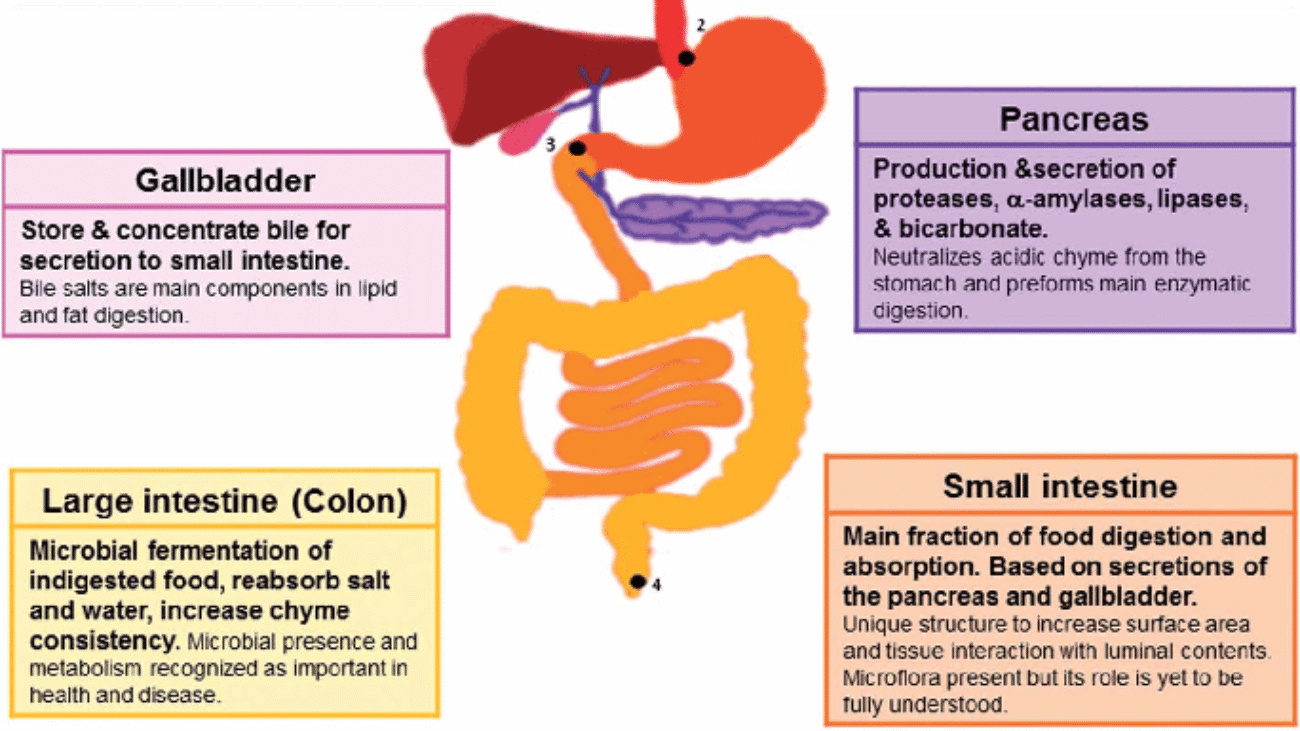

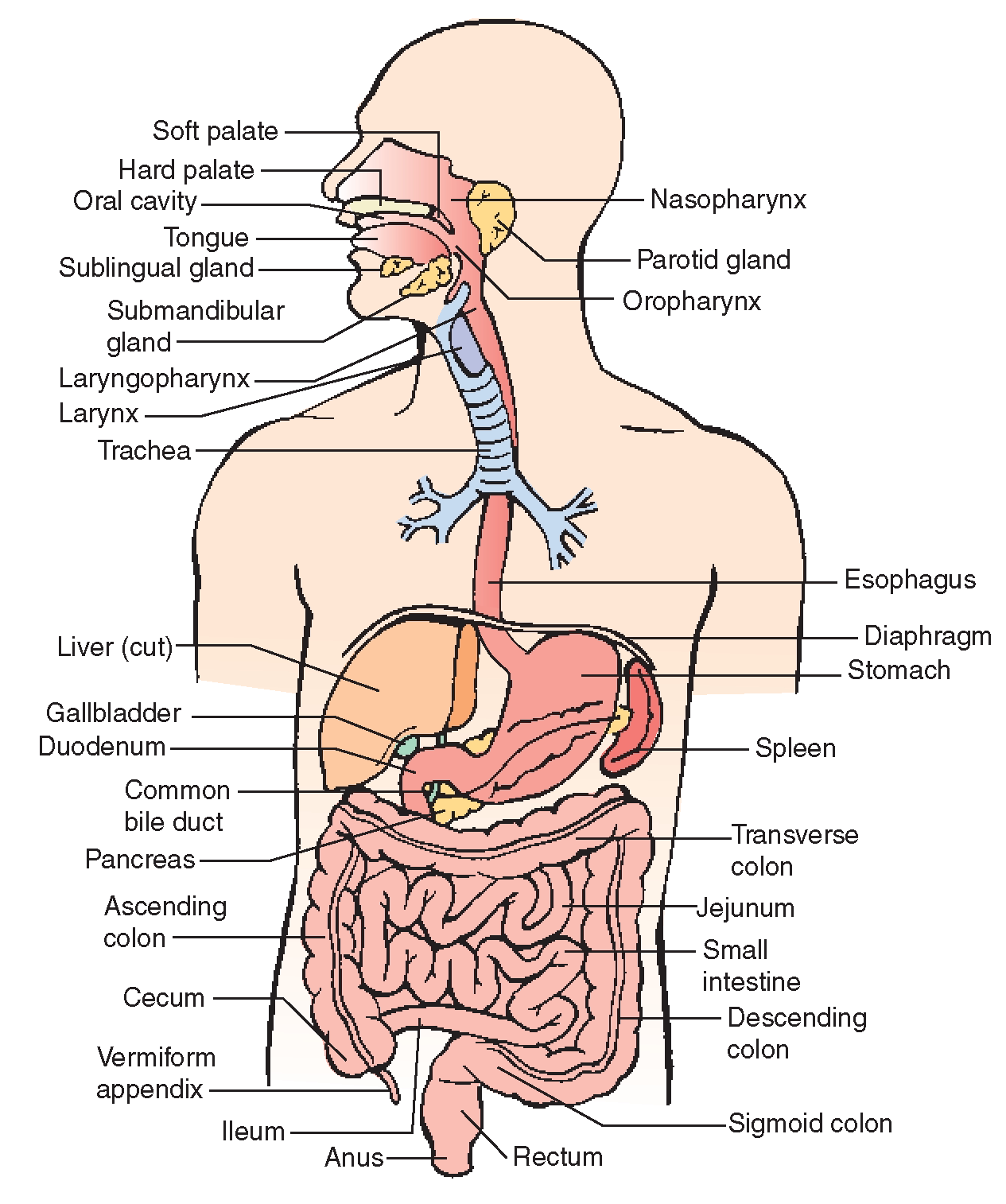

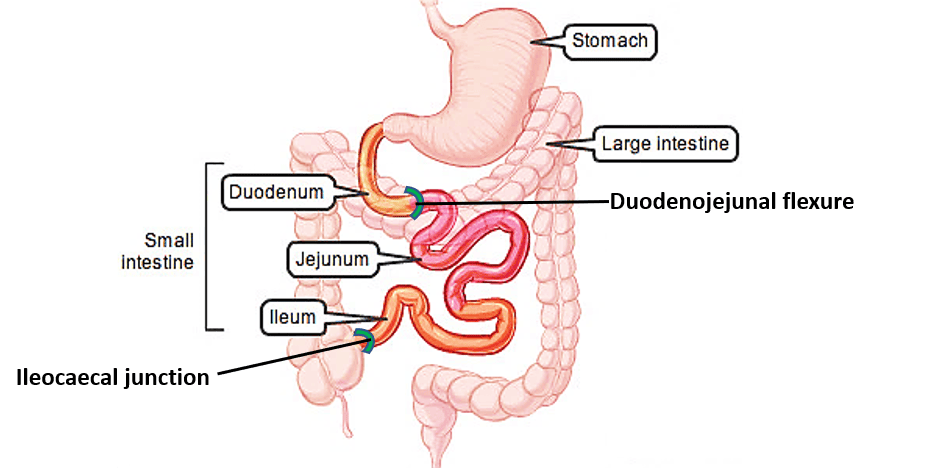

Small Intestines

The small intestine is the longest part of the alimentary canal, extending from the pylorus of the stomach to the ileocecal junction. Its primary function is the absorption of nutrients.

- Length: Approximately 6 meters (20 feet) long in a living person, but can be much longer post-mortem due to loss of muscle tone.

- Location: Occupies mainly the epigastric, umbilical, and hypogastric regions of the abdomen.

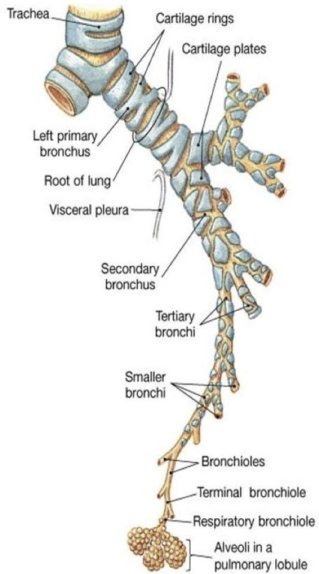

- Divisions: It is divided into three main parts:

- Duodenum

- Jejunum

- Ileum

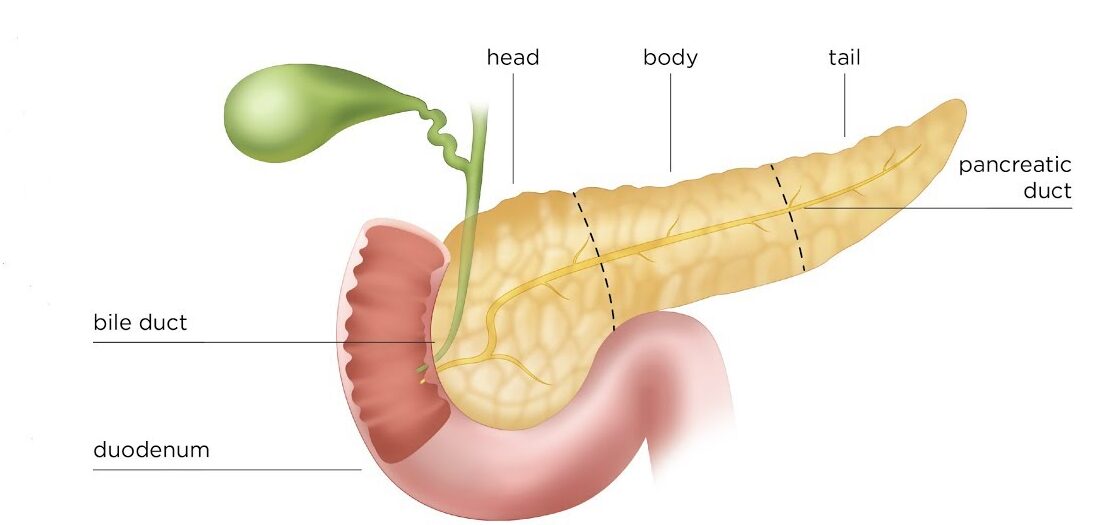

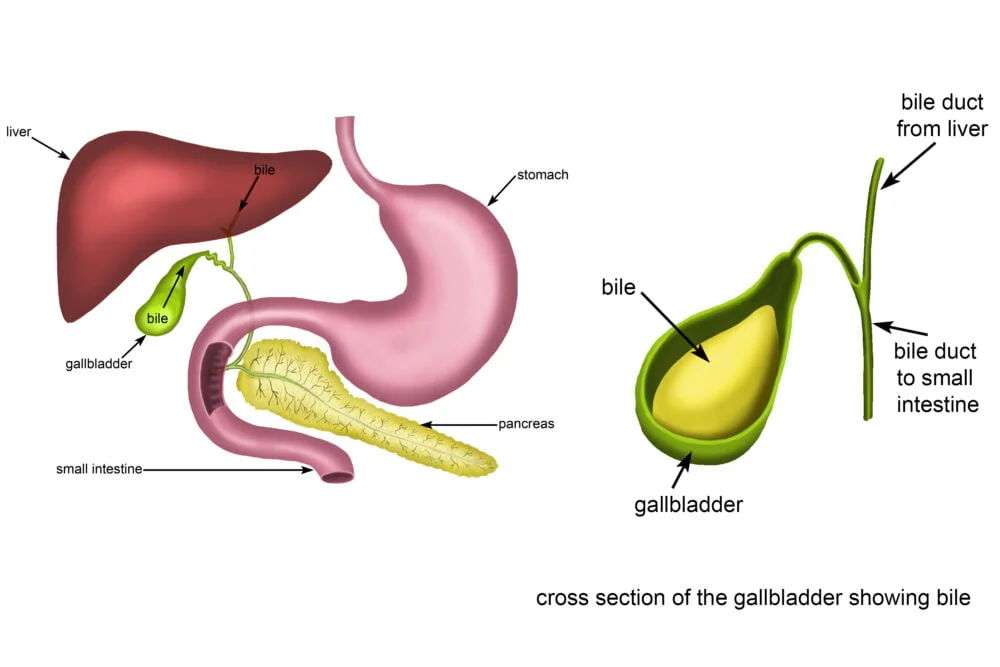

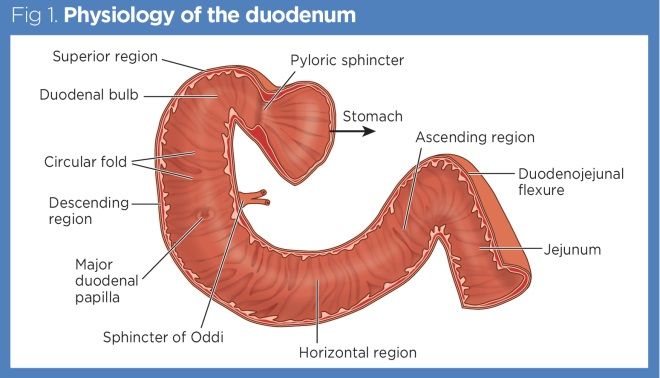

Duodenum

The duodenum is the first and shortest part of the small intestine.

- Length: Approximately 25 cm (10 inches) long.

- Course: It is C-shaped, wrapping around the head of the pancreas.

- Peritoneal Covering:

- The first 2.5 cm (1 inch) of the first part is intraperitoneal, resembling the stomach in structure and mobility. It is covered by peritoneum on its anterior and posterior surfaces, has the lesser sac behind it, and receives attachments from the lesser and greater omentum.

- The remainder of the duodenum (the vast majority) is retroperitoneal, meaning it is fixed to the posterior abdominal wall and covered by peritoneum only on its anterior surface.

- Key Feature: Receives the openings of the bile duct (carrying bile from the liver and gallbladder) and the pancreatic ducts (carrying digestive enzymes from the pancreas).

Parts of the Duodenum:

The duodenum is traditionally divided into four parts:

1. First Part (Superior Part)

- Length: Approximately 5 cm (2 inches) long.

- Location: Lies at the transpyloric plane (L1). The initial 2.5 cm is the most mobile, forming the "duodenal cap" or "ampulla." It runs upwards and backwards to the right of L1.

- Relations:

- Posteriorly: Lesser sac (initially), bile duct, portal vein, gastroduodenal artery, inferior vena cava (IVC).

- Anteriorly: Liver (quadrate lobe) and gallbladder.

- Superiorly: The opening into the lesser sac (epiploic foramen of Winslow).

- Inferiorly: Head of the pancreas.

2. Second Part (Descending Part)

- Length: Approximately 7.5 cm (3 inches) long.

- Location: Descends on the right side of the vertebral bodies L2 and L3, within the concavity of the head of the pancreas.

- Key Feature: Contains the major duodenal papilla (of Vater), where the bile duct and main pancreatic duct typically unite and open, and sometimes a minor duodenal papilla (for the accessory pancreatic duct).

- Relations:

- Anteriorly: Gallbladder (occasionally), right lobe of liver, coils of small intestines, transverse colon.

- Medially: Head of the pancreas, and the openings of the bile and pancreatic ducts.

- Laterally: Ascending colon, right colic flexure, right lobe of the liver.

- Posteriorly: Right kidney, right ureter, right psoas major muscle, IVC, aorta (more medially).

3. Third Part (Horizontal or Inferior Part)

- Length: Approximately 7.5 cm (3 inches) long.

- Location: Runs horizontally to the left, typically at the level of L3, inferior to the head of the pancreas.

- Key Feature: The superior mesenteric artery and vein cross anterior to this part.

- Relations:

- Superiorly: Head of the pancreas.

- Inferiorly: Coils of jejunum.

- Posteriorly: Aorta, IVC, right ureter, right psoas major muscle.

- Anteriorly: The root of the mesentery of the small intestines (containing the superior mesenteric artery and vein), and coils of jejunum.

4. Fourth Part (Ascending Part)

- Length: Approximately 5 cm (2 inches) long.

- Location: Ascends superiorly and to the left, reaching the level of L2, to join the jejunum at the duodenojejunal flexure.

- Key Feature: The duodenojejunal flexure is suspended by the ligament of Treitz (suspensory muscle of the duodenum), which attaches to the diaphragm.

- Relations:

- Anteriorly: Root of the mesentery and coils of jejunum.

- Posteriorly: Aorta and left psoas major muscle.

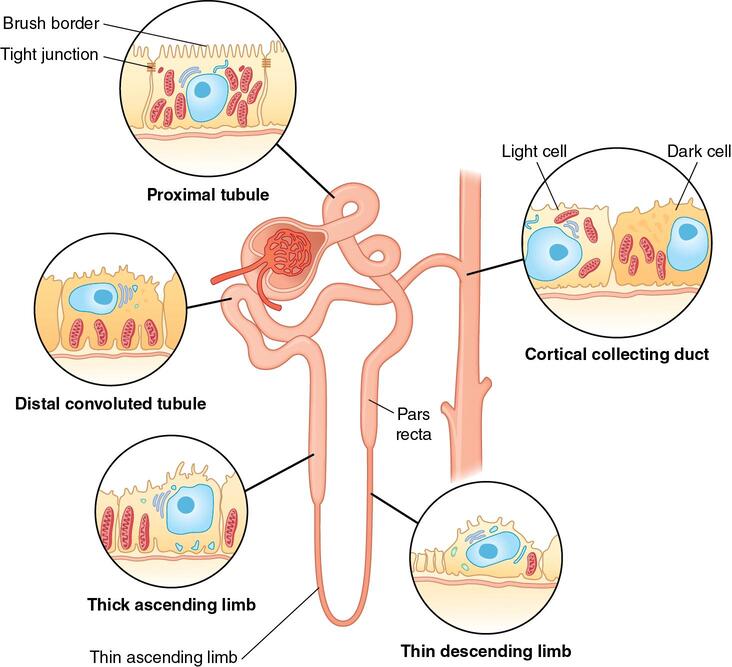

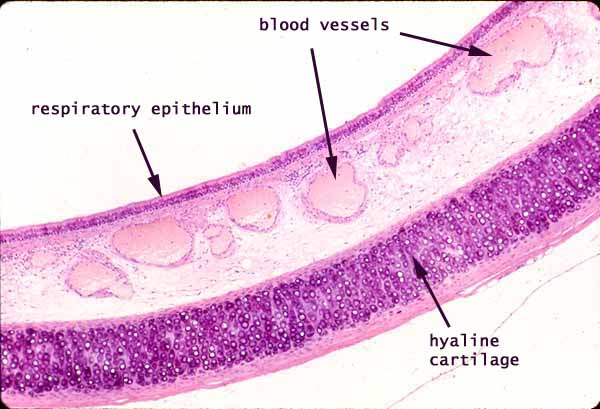

Histology of the Duodenum:

- Mucosa: The inner lining of the duodenum (and much of the small intestine) is thrown into numerous circular folds called plicae circulares (valves of Kerckring), which increase the surface area for absorption. The epithelium is simple columnar with abundant goblet cells and intestinal glands (crypts of Lieberkühn).

- Brunner's Glands: Unique to the duodenum, these are submucosal glands that produce alkaline mucus to neutralize acidic chyme from the stomach.

Blood Supply of the Duodenum:

The duodenum has a dual blood supply, forming an important anastomotic arcade.

- Superior Pancreaticoduodenal Artery: A branch of the gastroduodenal artery (from the common hepatic artery). Supplies the superior part of the duodenum.

- Inferior Pancreaticoduodenal Artery: A branch of the superior mesenteric artery. Supplies the inferior part of the duodenum.

- Veins and Lymphatics: Generally follow the arteries. Venous drainage is to the hepatic portal vein system.

Jejunum and Ileum

These two parts constitute the mobile, coiled portion of the small intestine, primarily responsible for nutrient absorption.

- Total Length: Approximately 6 meters (20 feet). The jejunum makes up the proximal 2/5ths, and the ileum makes up the distal 3/5ths.

- Mesentery: Both the jejunum and ileum are suspended from the posterior abdominal wall by a double layer of peritoneum called the mesentery of the small intestine. The root of this mesentery extends obliquely from the left of L2 to the right sacroiliac joint.

Differences Between Jejunum and Ileum:

While there is a gradual transition, some characteristic differences exist:

| Feature | Jejunum | Ileum |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Occupies the upper part of the peritoneal cavity, mostly to the left of the midline. | Occupies the lower part of the peritoneal cavity, mostly to the right of the midline, and within the pelvis. |

| Diameter | Wider (about 2-4 cm). | Narrower (about 1.5-3 cm). |

| Wall Thickness | Thicker-walled. | Thinner-walled. |

| Vascularity/Color | Redder, more vascular. | Paler, less vascular. |

| Plicae Circulares | More numerous, taller, and more closely packed. | Fewer, smaller, and more widely spaced; absent in the distal ileum. |

| Mesentery Fat | Fat deposition in the mesentery is near the root, with long windows (clear areas) in the mesentery between blood vessels. | Fat deposition extends from the root of the mesentery almost to the intestinal wall, with short windows or no windows in the mesentery. |

| Vascular Arcades | Forms one or two large, long arterial arcades. | Forms numerous short, smaller arterial arcades. |

| Vasa Recta | Longer and less branched. | Shorter and more branched. |

| Lymphoid Tissue | Solitary lymphoid follicles are present, but Peyer's patches are absent. | Large aggregations of lymphoid follicles called Peyer's patches are characteristic, especially in the distal ileum, along the antimesenteric border. |

Blood Supply of Jejunum and Ileum:

- Primarily supplied by jejunal and ileal branches that arise from the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). These arteries form arcades within the mesentery, from which straight vessels (vasa recta) arise to supply the intestinal wall.

- Veins and Lymphatics: Follow the arteries and drain into the superior mesenteric vein (eventually to the portal vein) and superior mesenteric lymph nodes, respectively.

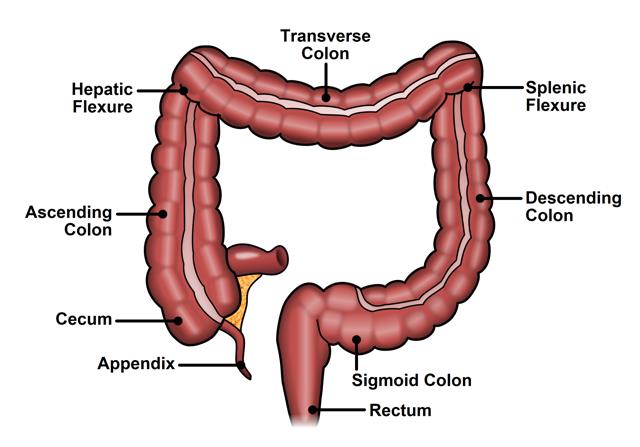

Large Intestines

The large intestine extends from the ileocecal junction to the anus.

- Primary Function: Absorption of water and electrolytes from undigested food material, and the storage and compaction of fecal matter prior to defecation.

- Divisions:

- Cecum

- Appendix

- Ascending Colon

- Transverse Colon

- Descending Colon

- Sigmoid Colon

- Rectum

- Anal Canal

Characteristic Features (except rectum and anal canal)

- Teniae Coli: Three distinct longitudinal bands of smooth muscle (converging at the appendix).

- Haustra: Sacculations or pouches of the colon, formed by the contraction of the teniae coli.

- Omental (Epiploic) Appendages: Small, fat-filled peritoneal pouches projecting from the serosal surface.

Cecum

The cecum is the blind-ended pouch that forms the beginning of the large intestine.

- Location: Lies in the right iliac fossa, below the level of the ileocecal junction.

- Mobility: It is relatively mobile despite lacking a mesentery in most individuals (it has peritoneal folds).

- Teniae Coli: The three teniae coli of the colon converge at the base of the cecum, providing a landmark for locating the appendix.

- Relations:

- Anteriorly: Anterior abdominal wall, coils of small intestines, greater omentum.

- Posteriorly: Psoas major muscle, iliacus muscle, femoral nerve, lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh, and the appendix.

- Blood Supply: From the anterior and posterior cecal arteries, which are branches of the ileocolic artery (a branch of the superior mesenteric artery).

- Veins and Lymphatics: Follow the arteries and drain into the superior mesenteric system.

Vermiform Appendix

The appendix is a narrow, tubular diverticulum extending from the cecum.

- Structure: Contains a large amount of lymphoid tissue.

- Length: Varies from 8 to 13 cm.

- Attachment: Attached to the posteromedial surface of the base of the cecum, approximately 2.5 cm below the ileocecal junction.

- Mesoappendix: It has its own peritoneal fold, the mesoappendix, which contains the appendicular artery.

- Location: Often lies in the right iliac fossa. Its base can be roughly located at McBurney's point, which is 1/3 of the way along a line joining the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the umbilicus.

- Common Positions: The appendix can lie in various positions relative to the cecum:

- Pelvic (Descending): Most common, descending into the pelvis.

- Retrocecal: Behind the cecum (second most common).

- Paracecal: Beside the cecum.

- Preileal: In front of the terminal ileum.

- Postileal: Behind the terminal ileum.

- Blood Supply: The appendicular artery, a branch of the posterior cecal artery (from the ileocolic artery).

- Veins and Lymphatics: Follow the artery.

- Nerve Supply: Superior mesenteric plexus (sympathetic for pain, vagal for parasympathetic).

Ascending Colon

The ascending colon is the part of the large intestine that travels upwards on the right side of the abdominal cavity.

- Length: Approximately 13 cm long.

- Course: Extends from the cecum, superior to the ileocolic junction, to the right colic flexure (hepatic flexure), where it turns left to become the transverse colon.

- Peritoneal Covering: It is typically retroperitoneal, fixed to the posterior abdominal wall.

- Relations:

- Anteriorly: Anterior abdominal wall, coils of small intestines, greater omentum.

- Posteriorly: Iliopsoas muscle, quadratus lumborum muscle, iliac crest, origin of transversus abdominis muscle, iliohypogastric nerve, ilioinguinal nerve, right kidney.

- Blood Supply: From the ileocolic artery and right colic artery (both branches of the superior mesenteric artery).

- Veins and Lymphatics: Follow the arteries and drain into the superior mesenteric system.

Transverse Colon

The transverse colon spans across the upper abdomen.

- Length: Approximately 38 cm long.

- Course: Extends from the right colic flexure to the left colic flexure (splenic flexure), where it turns inferiorly to become the descending colon.

- Mesentery: It is uniquely suspended by the transverse mesocolon, making it the most mobile part of the large intestine. The greater omentum is attached to its superior border, and the transverse mesocolon is attached to its inferior border.

- Relations:

- Anteriorly: Greater omentum and anterior abdominal wall.

- Posteriorly: Second part of the duodenum, head of the pancreas, coils of ileum and jejunum.

- Blood Supply: Has a dual blood supply due to its developmental origin (part from midgut, part from hindgut).

- Proximal 2/3 (right side): Supplied by the middle colic artery (a branch of the superior mesenteric artery).

- Distal 1/3 (left side): Supplied by the left colic artery (a branch of the inferior mesenteric artery).

- Veins and Lymphatics: Follow the arteries; veins drain into the superior and inferior mesenteric veins.

Descending Colon

The descending colon travels downwards on the left side of the abdominal cavity.

- Length: Approximately 25 cm long.

- Course: Extends from the left colic flexure to the sigmoid colon at the pelvic inlet.

- Peritoneal Covering: It is typically retroperitoneal, fixed to the posterior abdominal wall.

- Relations:

- Anteriorly: Coils of small intestines, greater omentum, and anterior abdominal wall.

- Posteriorly: Left kidney, left psoas major muscle, spleen (more superiorly), quadratus lumborum muscle, ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves, femoral nerve, lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh, iliac crest.

- Blood Supply: Primarily from the left colic artery (a branch of the inferior mesenteric artery).

- Veins and Lymphatics: Follow the arteries and drain into the inferior mesenteric system.

Sigmoid Colon

The sigmoid colon is the S-shaped terminal portion of the colon, connecting the descending colon to the rectum.

- Length: 25 to 38 cm long.

- Course: Extends from the pelvic brim (as a continuation of the descending colon) and ends at the level of S3 (the third sacral vertebra), where it transitions into the rectum.

- Mesentery: It has a distinct sigmoid mesocolon, making it very mobile.

- Relations:

- Anteriorly: In females, the uterus and upper part of the vagina. In males, the upper part of the urinary bladder.

- Posteriorly: Sacrum, rectum, coils of ileum.

- Blood Supply: From the sigmoid arteries (usually 2-4 branches) of the inferior mesenteric artery.

- Veins and Lymphatics: Follow the arteries and drain into the inferior mesenteric system.

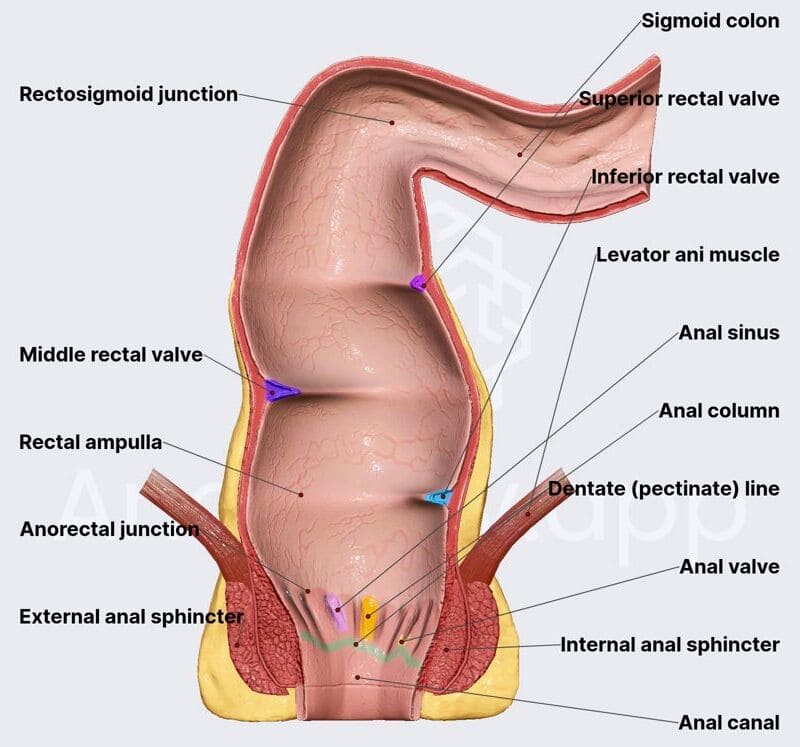

Rectum

The rectum is the final section of the large intestine, connecting the sigmoid colon to the anal canal.

- Length: Approximately 13 cm long.

- Course: Extends from the level of S3 (as a continuation of the sigmoid colon) and ends in front of the coccyx, where it pierces the pelvic diaphragm to become the anal canal. The puborectalis muscle forms a sling around the rectosigmoid junction, contributing to fecal continence.

- Peritoneal Covering:

- Upper 1/3: Covered by peritoneum on its anterior and lateral surfaces.

- Middle 1/3: Covered by peritoneum only on its anterior surface.

- Lower 1/3: Devoid of peritoneal covering (subperitoneal).

- Shape: It follows the concavity of the sacrum.

- Internal Features: The mucosa and circular muscle layer form three permanent transverse folds called transverse folds of the rectum (valves of Houston). The longitudinal muscle layer unites from the teniae coli to form a single continuous layer.

- Relations:

- Anteriorly:

- In females: Sigmoid colon (superiorly), uterus, and vagina.

- In males: Sigmoid colon (superiorly), urinary bladder, prostate, seminal vesicles, and vas deferens.

- Posteriorly: Sacrum, coccyx, piriformis muscle, coccygeus muscle, levator ani muscles.

- Anteriorly:

- Blood Supply: Has a rich, anastomosing blood supply from three main sources:

- Upper 1/3: Superior rectal artery (the terminal branch of the inferior mesenteric artery).

- Middle 1/3: Middle rectal arteries (branches of the internal iliac arteries).

- Lower 1/3: Inferior rectal arteries (branches of the internal pudendal arteries, which come from the internal iliac).

- Veins and Lymphatics: Follow the arteries. Venous drainage is crucial for portosystemic anastomoses. The superior rectal vein drains into the portal system, while the middle and inferior rectal veins drain into the systemic system. Lymphatics drain to internal iliac nodes.

Anal Canal

The anal canal is the terminal part of the large intestine and alimentary canal.

- Length: Approximately 4 cm long.

- Course: Begins at the level of the levator ani muscles and ends at the anus.

- Relations:

- Posteriorly: Anococcygeal body (a fibromuscular structure).

- Laterally: Ischiorectal fossae (fat-filled spaces).

- Anteriorly:

- In males: Perineal body, urogenital diaphragm, membranous urethra, and bulb of the penis.

- In females: Perineal body, urogenital diaphragm, and lower half of the vagina.

Mucosa of the Anal Canal:

The anal canal has a distinct mucosal lining that reflects its embryological development and innervation.

Upper Half (above the pectinate/dentate line)

- Epithelium: Simple columnar epithelium (similar to the rectum).

- Features: Has longitudinal folds called anal columns (of Morgagni), which contain terminal branches of the superior rectal artery and vein.

- Innervation: Visceral afferent (pain is dull, poorly localized). Supplied by superior rectal nerves.

- Blood Supply: Superior rectal artery and vein.

- Lymphatics: Drain to the inferior mesenteric lymph nodes.

Lower Half (below the pectinate/dentate line)

- Epithelium: Stratified squamous epithelium (non-keratinized initially, becoming keratinized at the anus).

- Features: No anal columns.

- Innervation: Somatic afferent (highly sensitive to pain, touch, temperature). Supplied by inferior rectal nerves (branches of the pudendal nerve).

- Blood Supply: Inferior rectal arteries and veins.

- Lymphatics: Drain to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

Anal Sphincters:

Two main sphincters control defecation:

- Internal Anal Sphincter:

- Composition: A thickened, involuntary (smooth) muscle layer formed by the circular muscle of the anal canal.

- Control: Under autonomic (involuntary) control. It maintains tonic contraction to prevent leakage of fecal material.

- External Anal Sphincter:

- Composition: Composed of voluntary (striated) muscle fibers. It consists of three parts (subcutaneous, superficial, and deep).

- Control: Under somatic (voluntary) control, allowing conscious control over defecation.

- Innervation: Pudendal nerve.

These sphincters work in coordination to control the expulsion of fecal material from the gut, maintaining continence.

Stomach & Intestines Quiz

Systems Anatomy

Enter your details to begin the examination.

🛡️ Privacy Note: Results are for tracking and certification purposes only.

Stomach & Intestines Quiz

Systems Anatomy

Preparing questions...

Exam Completed!

See your performance breakdown below.