Protein Chemistry and Amino Acids

Protein Chemistry : Overworkers

PROTEINS

Proteins are undoubtedly the most versatile and functionally diverse macromolecules in living systems. They are massive, complex organic compounds that are absolutely essential for every living cell, performing the vast majority of biological tasks. Indeed, if you can imagine a job that needs doing in a cell, chances are a protein is doing it.

Think of them as the true "workhorses" of the cell. While carbohydrates are primarily for immediate energy and structural components, and lipids for membranes and long-term energy storage, proteins execute an astonishing array of functions, making life possible and dynamic.

Origin of the Term "Protein"

The word "protein" is derived from the Greek word "proteios."

- "Proteios" means "holding the first place" or "primary."

This etymology beautifully underscores their profound significance: proteins are indeed of utmost importance to life, playing a primary and central role in virtually every biological process, from molecular interactions to macroscopic tissue function.

What are Proteins?

- Most Abundant Organic Molecules: Proteins are the most abundant and functionally diverse organic macromolecules found in living systems. They make up a significant portion of a cell's dry weight (often 50-70%), underscoring their ubiquitous presence and essential roles.

- Large Molecules (Biopolymers/Macromolecules): Proteins are large, complex molecules, often referred to as biopolymers or macromolecules due to their considerable size and intricate three-dimensional structures. Their precise folding is critical for their function.

- Made of Amino Acids: The Monomeric Units: They are constructed from smaller, repeating building blocks called amino acids. There are 20 common, genetically encoded amino acids that serve as the fundamental units for protein synthesis.

- Polymers of Amino Acids: The Polypeptide Chain: Proteins are fundamentally polymers of amino acids, linked together in long, unbranched chains. This linear sequence of amino acids is called a polypeptide chain. The sequence dictates the protein's unique 3D structure and, consequently, its specific function.

- Ubiquitous Presence: Proteins are found in every part of a cell and throughout the body – in cytoplasm, organelles, membranes, extracellular matrix, fluids (e.g., blood plasma, lymph), secretions, and even excretions. In human plasma alone, over 300 different types of proteins have been identified, each with distinct roles!

- Basis of Body Structure & Function: They form the fundamental basis of body structure, from the cytoskeleton of individual cells to the collagen in our bones and skin. Moreover, they are intimately involved in most of the body's functions and life processes, orchestrating the complex machinery of life.

- DNA Dictates Sequence (Central Dogma of Molecular Biology): The specific sequence of amino acids in a protein is precisely determined by the genetic information encoded in our DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid). This process, known as gene expression, involves transcription of DNA into messenger RNA (mRNA) and then translation of mRNA into a polypeptide chain on ribosomes. This precise control ensures that each protein has the correct sequence for proper folding and function.

Elemental Composition: What are Proteins Made Of?

While carbohydrates and lipids primarily consist of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, proteins possess a broader and more distinctive elemental signature:

- Carbon (C): 50 – 55%

- Hydrogen (H): 6 – 7.3%

- Oxygen (O): 19 – 24%

- Nitrogen (N): 13 – 19% (average is approximately 16%). This consistent presence of nitrogen in all proteins is the key differentiator that sets them apart from carbohydrates and lipids. This nitrogen is primarily found in the amino groups of their amino acid building blocks.

- Sulfur (S): 0 – 4% (present in the side chains of specific amino acids like Cysteine and Methionine, which are crucial for forming disulfide bonds and maintaining protein structure).

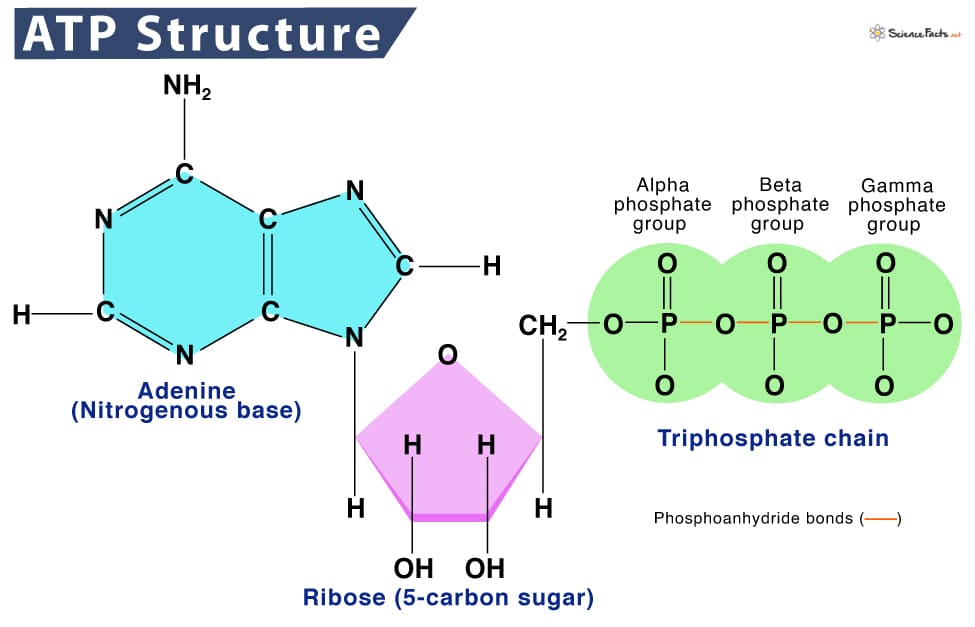

- Phosphorus (P): While not a primary constituent of the polypeptide backbone, phosphorus can be covalently attached to proteins through post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation of Serine, Threonine, or Tyrosine residues), which is a critical regulatory mechanism for protein activity. Some proteins also contain metal ions (e.g., Iron in hemoglobin, Zinc in many enzymes) as cofactors.

Functions of Proteins:

Proteins are truly the "workhorses" that carry out the cellular instructions and enable all aspects of life. Their functions are incredibly diverse and sophisticated:

Structural Support

Proteins provide the framework and strength for cells and tissues. Examples include Collagen (in skin, bone), Elastin (in blood vessels), Keratin (in hair, nails), and Actin/Tubulin (in the cytoskeleton).

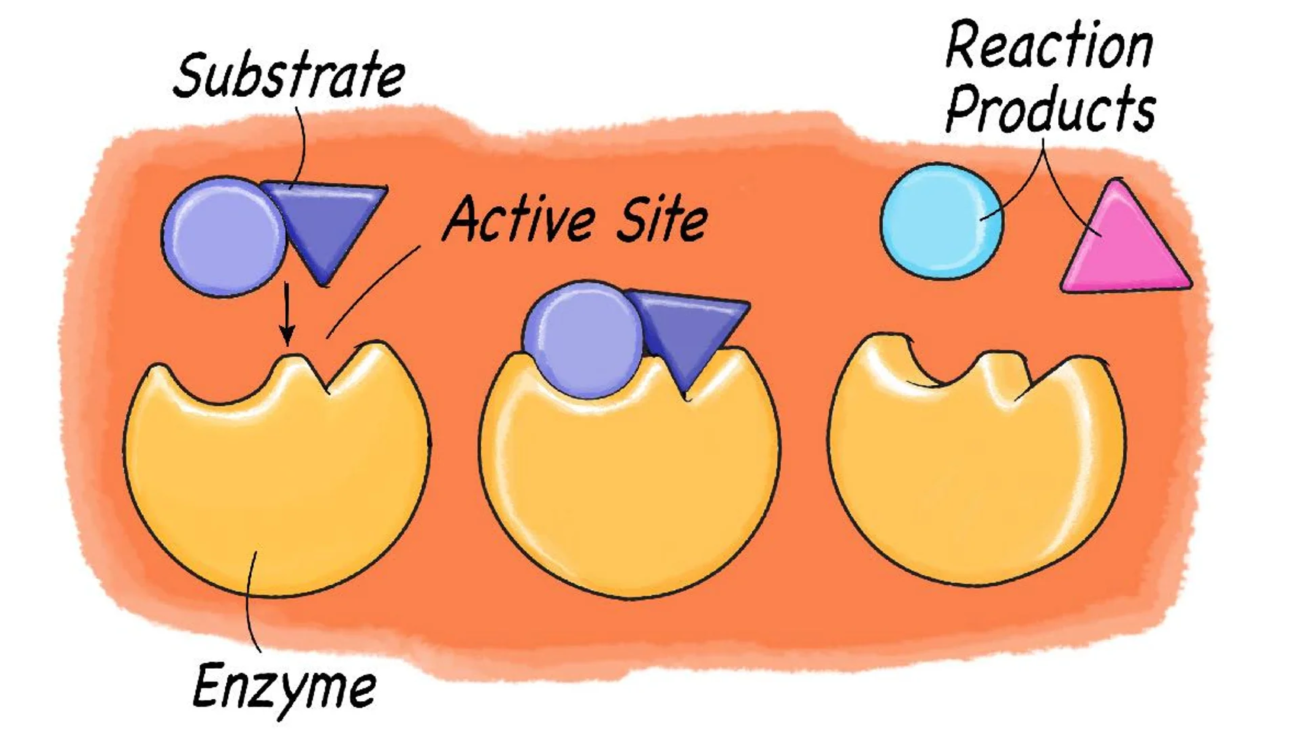

Catalysis (Enzymes)

As enzymes, proteins speed up nearly all biochemical reactions. Examples include Amylase (digests starch) and DNA Polymerase (synthesizes DNA). Deficiencies can cause metabolic diseases.

Transport and Storage

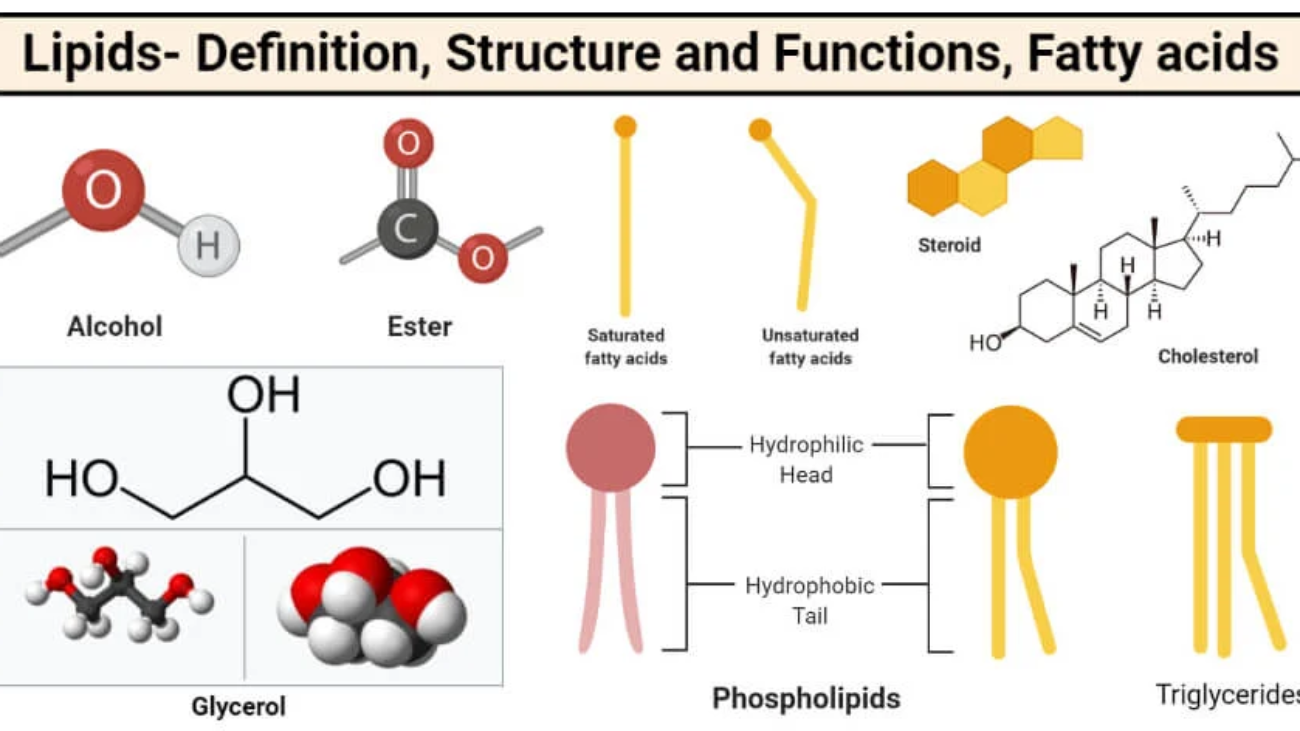

Proteins move essential molecules. Hemoglobin transports oxygen, Albumin transports fatty acids and drugs, Lipoproteins transport fats, and Transferrin transports iron. Ferritin stores iron inside cells.

Movement

Contractile proteins enable all forms of biological movement. Actin and Myosin power muscle contraction, while Dynein and Kinesin move cargo within cells and power cilia and flagella.

Regulation & Signaling

Proteins regulate physiological processes. Examples include protein hormones like Insulin, cell surface Receptors that transmit signals, and Transcription Factors that control gene expression.

Immune Defense

Proteins protect the body from pathogens. Antibodies (Immunoglobulins) recognize and neutralize foreign invaders, while Cytokines and Complement proteins coordinate the immune response.

Fluid Balance & Clotting

Plasma proteins like Albumin maintain osmotic pressure, preventing tissue edema. Coagulation factors like Fibrinogen and Thrombin are essential for blood clotting and preventing blood loss after injury.

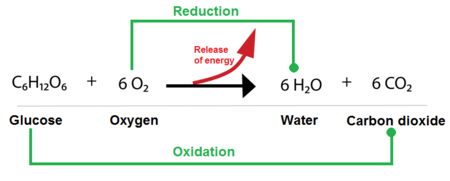

Energy Source

While not their primary function, proteins can be broken down into amino acids and used for energy during times of starvation or when other energy stores are depleted, through processes like gluconeogenesis.

Anatomy of Amino Acids: The Building Blocks of Proteins

Remember the functional group Amino? Indeed, it's central to these vital molecules!

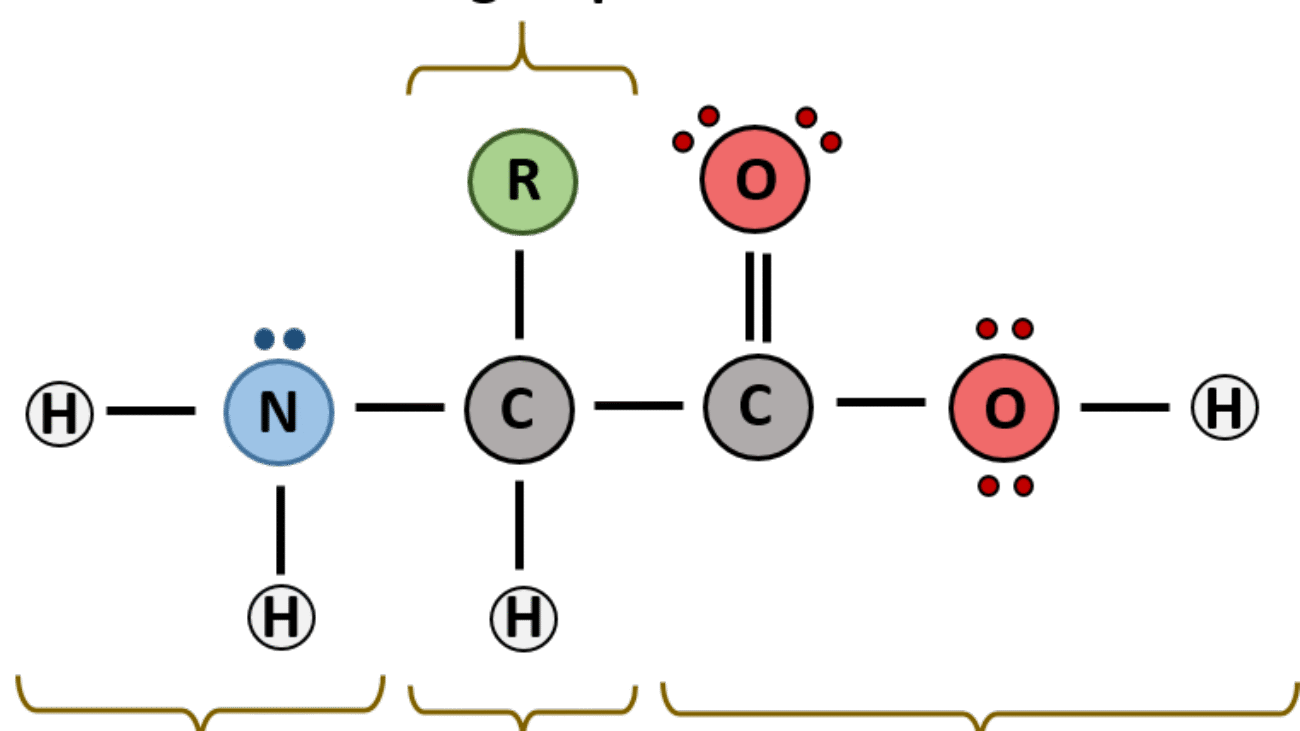

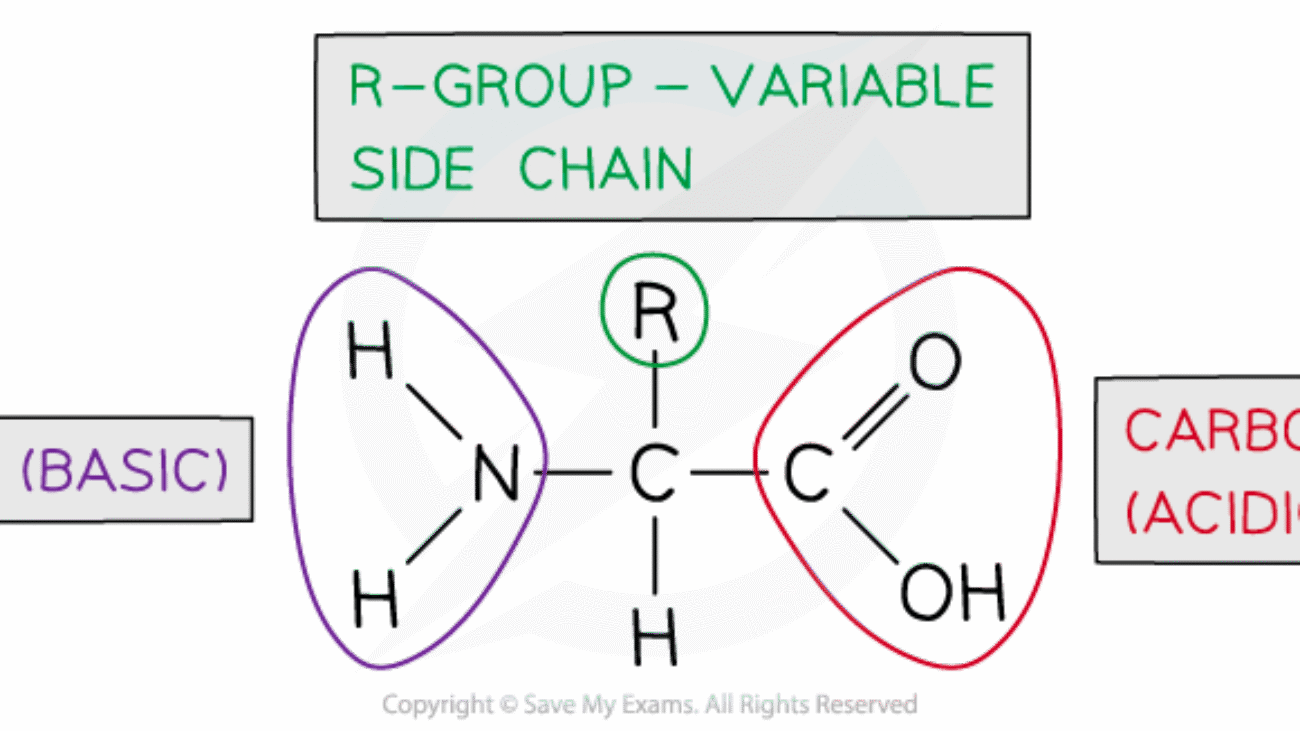

An amino acid is an organic molecule characterized by its unique chemical structure: it features a central carbon atom (the α-carbon) covalently bonded to four distinct groups:

- A basic amino group (−NH2)

- An acidic carboxyl group (−COOH)

- A hydrogen atom (−H)

- An organic R group (or side chain) that is unique to each specific amino acid.

The term amino acid is short for α-amino carboxylic acid, emphasizing the attachment of both the amino and carboxyl groups to the same carbon atom (the α-carbon).

The Basic Shape of Every Amino Acid (The "Amino Acid Blueprint")

Every single one of the 20 common genetically encoded amino acids shares a very similar basic blueprint:

- A central carbon (C) atom, called the alpha (α)-carbon. This carbon is the structural heart of the amino acid.

- Attached to this central α-carbon are four different chemical groups:

- An "Amino Group" (−NH2): This group contains nitrogen and is characterized by its basic properties. At physiological pH (the normal pH inside the body, approximately 7.4), the amino group is protonated, carrying a positive electrical charge (−NH3+).

- A "Carboxyl Group" (−COOH): This group contains carbon and oxygen and is characterized by its acidic properties. At physiological pH, the carboxyl group is deprotonated, carrying a negative electrical charge (−COO−).

- A "Hydrogen Atom" (−H): A single hydrogen atom that completes the valency of the α-carbon.

- A "Side Chain" (or "R-Group"): This is the most critical and defining part that makes each amino acid unique. The R-group can range from a single hydrogen atom (as in glycine) to complex cyclic structures. It is the R-group's specific chemical properties (e.g., size, shape, charge, polarity, hydrogen-bonding capacity) that determine the overall chemical behavior of the amino acid and, ultimately, the protein it forms.

At the normal pH inside the body (physiological pH, ~7.4), the amino group typically carries a positive charge (NH3+), and the carboxyl group carries a negative charge (COO−). This means that a single amino acid, even with both positive and negative parts, can have an overall neutral charge. When a molecule possesses both a positive and a negative charge, it's called a zwitterion.

- Zwitterion: A neutral molecule that has both a positive and a negative charge within its structure. Amino acids exist predominantly as zwitterions at physiological pH. It's important to distinguish this from a molecule that has no charge at all; a zwitterion has charges, but they balance each other out for an overall neutral molecule.

- Physiological pH (7.4): At this pH, the acidic carboxyl group is dissociated, forming a negatively charged carboxylate ion (COO−). Simultaneously, the basic amino group is protonated, forming a positively charged ammonium ion (NH3+). This simultaneous presence of opposite charges within the same molecule defines the zwitterionic state.

Monomers and Polymers: From Amino Acids to Proteins

To build the long, complex chains of proteins, we need individual building blocks. These single parts are called monomers. In this case, amino acids are the fundamental monomers. When many amino acid monomers come together and link chemically, they form polymers, which are the proteins.

In simple terms: Amino acids are the building blocks, and proteins are the intricate structures built from these blocks.

How Amino Acids Connect: The Peptide Bond

Amino acids are the fundamental monomer units that link together to form polypeptides, which then fold into functional proteins. There are 20 common amino acids that are genetically encoded and found in most proteins, although many other non-proteinogenic amino acids exist in nature (e.g., modified amino acids, neurotransmitters like GABA).

- Peptide Bond: Amino acids link together by a special type of covalent chemical bond called a peptide bond. This bond is the backbone of all proteins.

- Peptides: When two or more amino acids are linked together by peptide bonds, they form a molecule called a peptide. Peptides are essentially short chains of amino acids.

- If two amino acids combine, it's a dipeptide.

- If three amino acids combine, it's a tripeptide.

- If four amino acids combine, it's a tetrapeptide.

- If five amino acids combine, it's a pentapeptide.

- For chains with a relatively small number of amino acids (typically 2 to about 20-30), they are generally referred to as oligopeptides (from the Greek "oligo," meaning "few"). Examples include hormones like oxytocin or vasopressin, and some toxins.

- For longer chains of many amino acids (typically more than 30-50, extending to hundreds or thousands), they are called polypeptides (from the Greek "poly," meaning "many").

- From Polypeptide to Protein: A protein is a functional biological macromolecule made up of one or more polypeptide chains that have folded into a very specific, unique, and stable three-dimensional shape. This precise 3D structure is absolutely critical for its biological activity. So, a polypeptide is the linear chain of amino acids, and a protein is the functional, folded molecule that might contain one or more of these chains, often stabilized by additional interactions.

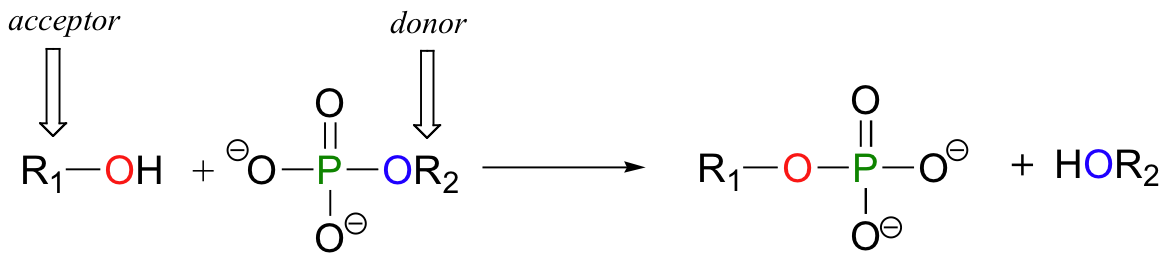

Formation of a Peptide Bond: Dehydration Synthesis

A peptide bond is formed through a condensation reaction (also known as dehydration synthesis).

- During this reaction, the carboxyl group (−COOH) of one amino acid reacts with the amino group (−NH2) of another amino acid.

- A molecule of water (H2O) is removed (lost) during the process. Specifically, the hydroxyl group (−OH) from the carboxyl end and a hydrogen atom (−H) from the amino end are removed.

- This forms a strong covalent amide linkage between the carbon of the carboxyl group of the first amino acid and the nitrogen of the amino group of the second amino acid. This new C-N bond is the peptide bond.

- Structure of the Peptide Bond: The peptide bond exhibits partial double-bond character due to resonance, which makes it rigid and planar. This rigidity is important for the structural integrity of the polypeptide backbone, limiting rotation around the bond and influencing the overall protein folding.

Breaking a Peptide Bond: Hydrolysis

A peptide bond can be broken through a reaction called hydrolysis.

- Hydrolysis involves the addition of a water molecule (H2O), which then breaks the covalent peptide bond. This process essentially reverses dehydration synthesis, regenerating the free carboxyl group and free amino group.

- In biological systems, this reaction is typically catalyzed by specific enzymes called proteases (or peptidases), which are essential for protein digestion, turnover, and regulation.

Amino Acid Residues: The Components of a Polypeptide

When amino acids link together to form a peptide, they lose some atoms (the elements of water) in the process. The amino acid that has been incorporated into the chain, now missing those elements, is no longer a "free amino acid" with its full amino and carboxyl groups. Instead, it's now a "leftover part" or a "component" of the larger chain. For this reason:

- An amino acid unit in a peptide (or protein) is often called a "residue."

- Proteins are polymers of amino acid residues, with each residue joined to its neighbor by a specific type of covalent bond called a peptide bond.

Properties of Amino Acids

- Solubility: Most amino acids are soluble in water and insoluble in non-polar organic solvents. This is primarily due to their charged (zwitterionic) nature and the presence of polar functional groups within their R-chains, allowing them to form strong hydrogen bonds with water molecules.

- Melting Points: They melt at higher temperatures (typically > 200°C) compared to other organic compounds of similar size. This high melting point is a direct consequence of their zwitterionic nature, where strong electrostatic forces (ionic bonds) exist between the oppositely charged groups of adjacent amino acid molecules in their crystalline state, requiring significant energy to break.

- Taste:

- Sweet: Glycine, Alanine, Valine (and some other small, non-polar or uncharged polar amino acids). This is due to their ability to bind to taste receptors.

- Bitter: Arginine, Isoleucine, Phenylalanine (often larger, more hydrophobic, or basic amino acids).

- Tasteless: Leucine (and some others).

- Umami: Glutamate (monosodium glutamate, MSG, is a common flavor enhancer).

- Note: The taste profiles are complex and depend on interactions with specific taste receptors.

- Optical Isomers (Stereoisomerism):

- All amino acids, except glycine, possess an asymmetric (chiral) α-carbon atom. A chiral carbon is bonded to four different groups.

- This chirality gives rise to optical isomers (enantiomers), which are non-superimposable mirror images of each other. These are designated as D- and L-stereoisomers.

- Nearly all biological compounds with a chiral center occur naturally in only one stereoisomeric form.

- The amino acid residues in proteins are exclusively L-stereoisomers. While D-amino acids exist in nature (e.g., in bacterial cell walls, some peptide antibiotics), they are generally not incorporated into proteins during ribosomal synthesis in higher organisms. This strict stereospecificity is fundamental to protein structure and function.

- Glycine is the exception because its R-group is simply a hydrogen atom, making its α-carbon bonded to two identical hydrogen atoms, hence it is achiral.

- Ampholytes or Zwitterions (Amphoteric Nature):

- Amino acids are ampholytes, meaning they contain both an acidic group (the carboxyl group, −COOH) which can donate a proton, and a basic group (the amino group, −NH2) which can accept a proton. This allows them to act as both an acid and a base depending on the pH of the surrounding medium.

- As discussed, at physiological pH, they exist as zwitterions, bearing both a positive (NH3+) and a negative (COO−) charge, resulting in an overall neutral molecule.

- The isoelectric point (pI) is the specific pH at which an amino acid (or protein) exists predominantly as a zwitterion, with an equal number of positive and negative charges, resulting in a net charge of zero. At its pI, an amino acid will not migrate in an electric field.

- Amphoteric Nature: This ability to act as both an acid and a base is crucial for proteins to function as buffers in biological systems, helping to resist changes in pH and maintain the narrow pH range required for cellular processes.

Ionized Nature of Amino Acid (Diagrammatic Representation)

R

|

H₂N − C − COOH (General form - often drawn this way for simplicity,

| but not how it primarily exists in solution)

H

At highly acidic pH (low pH, excess H+):

- The carboxyl group is protonated (−COOH).

- The amino group is protonated (−NH3+).

- Overall charge: Cationic (net positive charge).

R

|

+H₃N − CH − COOH (Cationic form at low pH)

At physiological pH (neutral pH, ~7.4):

- The carboxyl group is deprotonated (−COO−).

- The amino group is protonated (−NH3+).

- Overall charge: Zwitterionic (net neutral charge).

R

|

+H₃N − CH − COO− (Zwitterion or dipolar ion at physiological pH)

At highly basic pH (high pH, low H+):

- The carboxyl group is deprotonated (−COO−).

- The amino group is deprotonated (−NH2).

- Overall charge: Anionic (net negative charge).

R

|

H₂N − CH − COO− (Anionic form at high pH)

Classification of the 20 Common Amino Acids (Based on R-Groups)

As we discussed, the "Side Chain" or "R-Group" is the only part that varies among the 20 common amino acids found in proteins. These R-groups have different chemical properties that dictate the amino acid's behavior and, consequently, the protein's overall structure and function.

We can classify these 20 amino acids into several groups based on the polarity and charge of their R-groups at physiological pH (around 7.4).

Group 1: Amino Acids with Nonpolar, Aliphatic R-Groups

These R-groups are generally "water-fearing" (hydrophobic) because they consist mainly of hydrocarbons (carbon and hydrogen atoms), which do not readily form hydrogen bonds with water. They tend to cluster together in the interior of proteins, away from the aqueous environment.

| Name | 3-Letter | 1-Letter | Structure of R-Group | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycine | Gly | G | -H (just a hydrogen atom) | Smallest & simplest. Only non-chiral amino acid. Allows for great flexibility in protein structure due to its small size. |

| Alanine | Ala | A | -CH₃ (methyl group) | Small, unreactive. Contributes to the hydrophobic core of proteins. |

| Valine | Val | V | -CH(CH₃)₂ (isopropyl group) | Branched hydrocarbon chain. More hydrophobic than Alanine. |

| Leucine | Leu | L | -CH₂CH(CH₃)₂ (isobutyl group) | Branched hydrocarbon chain. Very hydrophobic. Common in the interior of proteins. |

| Isoleucine | Ile | I | -CH(CH₃)CH₂CH₃ (sec-butyl group) | Branched hydrocarbon chain. Stereoisomer of Leucine (same atoms, different arrangement). Very hydrophobic. |

| Methionine | Met | M | -CH₂CH₂SCH₃ (contains a sulfur atom) | Contains a sulfur atom (thioether linkage), but it's largely nonpolar. Always the first amino acid in a newly synthesized polypeptide chain (start codon). |

| Proline | Pro | P | -CH₂CH₂CH₂- (cyclic structure) | Unique cyclic structure where its R-group is bonded to both the α-carbon and the α-amino group, forming a rigid ring. Causes "kinks" in polypeptide chains. Often found in turns. |

Group 2: Amino Acids with Aromatic R-Groups

These R-groups contain bulky ring structures, which makes them generally hydrophobic. They can also absorb UV light at 280 nm, a property used to quantify proteins.

| Name | 3-Letter | 1-Letter | Structure of R-Group | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenylalanine | Phe | F | -CH₂- (phenyl group) | Very hydrophobic due to the bulky phenyl ring. |

| Tyrosine | Tyr | Y | -CH₂- (phenyl group with -OH) | Aromatic ring with a hydroxyl (-OH) group. The -OH group can form hydrogen bonds, making it slightly more polar than Phenylalanine. Can be phosphorylated, important for cell signaling. |

| Tryptophan | Trp | W | -CH₂- (indole group, double ring with N) | Largest and most hydrophobic aromatic amino acid. Indole ring can form hydrogen bonds through its N-H group. Precursor to serotonin and niacin. |

Group 3: Amino Acids with Uncharged, Polar R-Groups

These R-groups contain functional groups that can form hydrogen bonds with water (like -OH, -SH, -CONH₂), making them "water-loving" (hydrophilic). They tend to be found on the surface of proteins, interacting with the aqueous environment.

| Name | 3-Letter | 1-Letter | Structure of R-Group | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serine | Ser | S | -CH₂OH (hydroxyl group) | Contains a hydroxyl group. Can form hydrogen bonds. Can be phosphorylated, important for cell signaling. |

| Threonine | Thr | T | -CH(OH)CH₃ (hydroxyl group) | Contains a hydroxyl group. Can form hydrogen bonds. Can be phosphorylated. |

| Cysteine | Cys | C | -CH₂SH (sulfhydryl group) | Contains a sulfhydryl (-SH) group. Crucially, two Cysteine residues can form a disulfide bond (-S-S-), a strong covalent bond that stabilizes protein structure. |

| Asparagine | Asn | N | -CH₂CONH₂ (amide group) | Contains an amide group. Can form hydrogen bonds. |

| Glutamine | Gln | Q | -CH₂CH₂CONH₂ (amide group) | Contains an amide group. Can form hydrogen bonds. Longer side chain than Asparagine. |

Group 4: Amino Acids with Positively Charged R-Groups (Basic)

These R-groups contain an extra amino group or other nitrogen-containing groups that can accept a proton (H⁺) at physiological pH, making them positively charged (basic). They are very hydrophilic and are usually found on the surface of proteins.

| Name | 3-Letter | 1-Letter | Structure of R-Group | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lysine | Lys | K | -CH₂CH₂CH₂CH₂NH₃⁺ (primary amine) | Long hydrocarbon chain with a terminal primary amino group. Strongly basic and positively charged at neutral pH. |

| Arginine | Arg | R | -CH₂CH₂CH₂NHC(=NH)NH₂⁺ (guanidinium group) | Contains a guanidinium group, which is the most strongly basic functional group in amino acids. Always positively charged at neutral pH. |

| Histidine | His | H | -CH₂- (imidazole group) | Contains an imidazole ring. Unique in that its side chain can be either uncharged or positively charged at physiological pH (pKa near 6.0). This makes it important in enzyme active sites, where it can act as both a proton donor and acceptor. |

Group 5: Amino Acids with Negatively Charged R-Groups (Acidic)

These R-groups contain an extra carboxyl group that can donate a proton (H⁺) at physiological pH, making them negatively charged (acidic). They are very hydrophilic and are usually found on the surface of proteins, often involved in ionic interactions.

| Name | 3-Letter | 1-Letter | Structure of R-Group | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspartate | Asp | D | -CH₂COO⁻ (carboxylic acid group) | Contains a second carboxyl group. Negatively charged at neutral pH. Often participates in ionic bonds and salt bridges. |

| Glutamate | Glu | E | -CH₂CH₂COO⁻ (carboxylic acid group) | Contains a second carboxyl group. Negatively charged at neutral pH. Longer side chain than Aspartate. |

Understanding and Naming Peptide Sequences

A peptide or protein sequence is the specific linear order of amino acids linked together by peptide bonds. There are very specific conventions for how these sequences are written and read, which are essential for clear, unambiguous communication in biochemistry and molecular biology.

The Directionality of Peptides: N-terminus and C-terminus

Every peptide or polypeptide chain exhibits a distinct directionality, meaning it has a defined "start" and an "end." This intrinsic polarity is fundamental to how proteins are synthesized, fold, and function.

- Amino-terminal end (N-terminus): This is conventionally considered the beginning of the peptide chain. It is characterized by having a free, unbonded α-amino group (−NH3+) at one end of the first amino acid in the sequence. By convention, this end is always written on the left side of the sequence.

- Carboxyl-terminal end (C-terminus): This is conventionally considered the end of the peptide chain. It is characterized by having a free, unbonded α-carboxyl group (−COO−) at the other end of the last amino acid in the sequence. By convention, this end is always written on the right side of the sequence.

Reading Peptide Sequences

Peptide sequences are always read from left to right, starting from the N-terminus and proceeding sequentially towards the C-terminus.

Each amino acid unit within the peptide chain, after forming peptide bonds, is referred to as an amino acid residue. This term emphasizes that each amino acid has lost the elements of water (a hydrogen atom from its amino group and a hydroxyl group from its carboxyl group) when participating in the formation of a peptide bond. Within the chain, only the R-group and the α-carbon, along with parts of the backbone, remain.

Representing Amino Acids in a Sequence: Abbreviations

To simplify the writing and reading of often very long protein sequences, standard abbreviations are universally used for the 20 common genetically encoded amino acids:

- Three-Letter Code: Each amino acid has a unique three-letter abbreviation. These are often used when the structure is being discussed in more detail, for shorter peptides, or in academic texts to enhance readability. (e.g., Ala for Alanine, Gly for Glycine, Ser for Serine). The first letter is usually capitalized, followed by two lowercase letters.

- One-Letter Code: For very long sequences (like entire proteins or genomic sequences), a single-letter code for each amino acid is used to save space, facilitate database storage, and make sequence comparisons visually easier. This is extremely common in bioinformatics and molecular biology.

Quick reference for the 20 common amino acids and their abbreviations:

| Amino Acid | Three-Letter Code | One-Letter Code |

|---|---|---|

| Alanine | Ala | A |

| Arginine | Arg | R |

| Asparagine | Asn | N |

| Aspartate | Asp | D |

| Cysteine | Cys | C |

| Glutamine | Gln | Q |

| Glutamate | Glu | E |

| Glycine | Gly | G |

| Histidine | His | H |

| Isoleucine | Ile | I |

| Leucine | Leu | L |

| Lysine | Lys | K |

| Methionine | Met | M |

| Phenylalanine | Phe | F |

| Proline | Pro | P |

| Serine | Ser | S |

| Threonine | Thr | T |

| Tryptophan | Trp | W |

| Tyrosine | Tyr | Y |

| Valine | Val | V |

Note: For cases where the exact amide status is unknown or ambiguous:

- "B" can represent Asx (Aspartic acid or Asparagine).

- "Z" can represent Glx (Glutamic acid or Glutamine).

- "X" represents an unknown or unspecified amino acid.

How to "Name" or Write a Peptide Sequence

When asked to "name" a peptide or write its sequence, you list the amino acid residues in order from the N-terminus to the C-terminus, using their standard abbreviations.

- For shorter peptides: You can use three-letter codes separated by hyphens to clearly delineate each residue.

Example: Ala-Gly-Ser - For longer peptides or proteins: You primarily use one-letter codes, often written consecutively without separators, unless referring to specific segments or indicating post-translational modifications.

Example: AGS (for Ala-Gly-Ser)

Example: The sequence Asp-Lys-Gln-His-Cys-Arg-Phe can be written as DKQHCRF.

Example Practice: Determining a Peptide Sequence from its Structure

Let's carefully examine this peptide structure to determine its sequence.

- 1st Residue (from N-terminus): R-group is −CH3.

- 2nd Residue: R-group is a phenyl group with an −OH attached to the ring (i.e., −CH2−C6H4−OH).

- 3rd Residue: R-group is −CH2CONH2.

- 4th Residue (at C-terminus): R-group is −H.

Step-by-step identification:

- Identify the N-terminus: This is on the far left, characterized by the free H3N+ group.

- Identify the C-terminus: This is on the far right, characterized by the free COO− group.

- Identify each amino acid residue from N- to C-terminus based on its R-group:

- 1st Residue (N-terminus): R-group is −CH3. This R-group corresponds to Alanine (Ala).

- 2nd Residue: R-group is a phenyl group with an −OH attached (−CH2−C6H4−OH). This R-group corresponds to Tyrosine (Tyr).

- 3rd Residue: R-group is −CH2CONH2. This R-group corresponds to Asparagine (Asn).

(−CH2CONH2 is characteristic of Asparagine.) - 4th Residue (C-terminus): R-group is −H. This R-group corresponds to Glycine (Gly).

- Write the sequence using the standard abbreviations:

- Using three-letter codes: Ala-Tyr-Asn-Gly

- Using one-letter codes: ATNG

Other Classifications of Amino Acids

Beyond the R-group classification (which is by far the most common in structural biochemistry and determines an amino acid's direct contribution to protein structure and interaction), amino acids can also be classified based on their chemical properties, nutritional requirements, and metabolic fates. These classifications provide different lenses through which to understand their roles in biology.

II. Chemical Classification

This classification often overlaps with the R-group classification (e.g., polar, nonpolar, charged) but can highlight specific chemical properties not solely related to polarity or charge. It categorizes amino acids based on the overall nature of their side chains and their behavior in solution.

- Neutral Amino Acids: These amino acids have an equal number of amino (−NH2) and carboxyl (−COOH) groups in their structure, with no additional acidic or basic groups in their R-chain that would contribute a net charge at physiological pH. Their R-groups can be either nonpolar (hydrophobic) or polar but uncharged.

Examples: Glycine, Alanine, Valine, Leucine, Isoleucine, Methionine, Proline, Phenylalanine, Tryptophan (nonpolar/hydrophobic); Serine, Threonine, Cysteine, Asparagine, Glutamine, Tyrosine (polar uncharged). - Acidic Amino Acids: These possess an additional carboxyl group (−COOH) within their R-chain, in addition to the α-carboxyl group. This extra acidic group can deprotonate at physiological pH, giving them a net negative charge at pH 7.4.

Examples: Aspartate (Asp) and Glutamate (Glu). (Note: When protonated, they are called aspartic acid and glutamic acid, respectively). - Basic Amino Acids: These contain an additional amino group (−NH2) or other nitrogenous groups capable of accepting a proton within their R-chain. These groups become protonated at physiological pH, giving them a net positive charge at pH 7.4.

Examples: Lysine (Lys), Arginine (Arg), Histidine (His). (Histidine's imidazole ring has a pKa near physiological pH, meaning it can be uncharged or positively charged depending on the exact pH). - Sulfur-Containing Amino Acids: These are characterized by the presence of sulfur atoms in their R-groups.

Examples: Cysteine (Cys) and Methionine (Met). Cysteine's thiol (−SH) group is particularly reactive and crucial for forming disulfide bonds (−S−S−), which are covalent linkages important for stabilizing protein tertiary and quaternary structures. Methionine, containing a thioether, is less reactive but often serves as the initiating amino acid in protein synthesis and as a methyl donor. - Aromatic Amino Acids: These amino acids contain an aromatic ring structure within their R-groups. These rings are generally hydrophobic and can absorb UV light, a property used in protein quantification.

Examples: Phenylalanine (Phe), Tyrosine (Tyr), Tryptophan (Trp). - Imino Acid: Technically, Proline (Pro) is often classified separately as an imino acid rather than a true amino acid. This is because its nitrogen atom (from the α-amino group) is part of a cyclic structure (a five-membered ring with the R-group), forming a secondary amine (−NH−) rather than a primary amine (−NH2). This unique structure gives proline distinct conformational properties, introducing kinks in polypeptide chains.

III. Nutritional Classification

This classification is from a dietary perspective, particularly for humans. It categorizes amino acids based on whether the human body can synthesize them de novo (from scratch) or if they must be obtained through the diet.

Essential

The body cannot synthesize these, so they must be obtained from the diet. There are 9: Histidine, Isoleucine, Leucine, Lysine, Methionine, Phenylalanine, Threonine, Tryptophan, and Valine.

Non-Essential

The body can synthesize these from other compounds, so they are not required in the diet. Examples include Alanine, Aspartate, Glycine, and Serine.

Conditionally Essential

Normally non-essential, but become essential during illness, rapid growth, or stress. Examples include Arginine, Cysteine, Tyrosine, and Glutamine.

Mnemonic (a common one, often extended): PVT TIM HALL (Phenylalanine, Valine, Threonine, Tryptophan, Isoleucine, Methionine, Histidine, Arginine, Leucine, Lysine). Note: Arginine is often considered conditionally essential, see below.

IV. Metabolic Classification

This classification categorizes amino acids based on the fate of their carbon skeletons after the amino group has been removed (a process called deamination or transamination). This dictates how the body uses them for energy production or to synthesize other crucial biomolecules.

Glucogenic

These can be converted into glucose via gluconeogenesis. Their carbon skeletons are degraded to intermediates like pyruvate or oxaloacetate. Examples include Alanine, Glycine, and Serine.

Ketogenic

These can be converted into ketone bodies or their precursors (acetyl-CoA). Leucine and Lysine are the only two amino acids that are purely ketogenic.

Both

These can be degraded into intermediates that form both glucose and ketone bodies. Examples include Isoleucine, Phenylalanine, Tyrosine, and Tryptophan.

The Biuret Test: Detecting Proteins and Peptides

The Biuret test is a classic qualitative (and semi-quantitative) chemical test used to detect the presence of proteins and peptides in a solution.

Principle:

The Biuret test specifically detects the presence of peptide bonds. It relies on the ability of copper(II) ions (Cu2+) in an alkaline solution to form a distinctive violet-colored chelate complex with compounds containing two or more peptide bonds. A single amino acid or a dipeptide will not give a positive Biuret test.

Reagents:

- Biuret reagent: This reagent typically contains:

- Dilute copper(II) sulfate (CuSO4) as the source of Cu2+ ions.

- A strong alkaline solution (e.g., sodium hydroxide, NaOH, or potassium hydroxide, KOH) to provide the necessary alkaline environment.

- Often, potassium sodium tartrate (Rochelle salt) is included to chelate the Cu2+ ions, keeping them in solution and stabilizing the complex, preventing their precipitation as copper hydroxide.

Procedure:

- Add a small amount of the sample solution (e.g., protein solution, tissue homogenate) to a clean test tube.

- Add an equal volume (or a specified ratio, typically 1:1 or 2:1 sample to reagent) of Biuret reagent to the test tube.

- Mix the contents well (gently shaking or inverting) and allow it to stand for a few minutes (e.g., 5-30 minutes) at room temperature for the color to develop.

- Observe for a color change.

Results:

- Positive Result: The solution develops a violet or purple color. This clearly indicates the presence of proteins or peptides containing at least two peptide bonds. The intensity of the violet color is generally proportional to the number of peptide bonds present, and thus, often to the concentration of protein in the sample. A pinkish-purple color may indicate shorter peptides.

- Negative Result: The solution remains blue (the original color of the copper sulfate in the reagent). This indicates the absence of significant amounts of protein or peptides containing sufficient peptide bonds to form the complex. Individual amino acids or dipeptides will yield a negative result.

Applications:

- Detecting proteins in various biological solutions (e.g., blood plasma, cell lysates, culture media).

- Estimating protein concentration (when performed quantitatively using a spectrophotometer to measure absorbance at 540 nm, by comparing to a standard curve).

- Monitoring protein purification steps, to track the presence and enrichment of protein.

- Clinical diagnostics (e.g., historically used to detect protein in urine, though more specific and sensitive tests are typically employed today).

- Educational demonstrations in biochemistry and biology laboratories.

The Four Levels of Protein Structure

Proteins are not just linear chains of amino acids; they fold into precise, intricate three-dimensional structures that are absolutely essential for their biological function. This complex folding process can be described at four hierarchical levels.

1. Primary Structure (1° Structure)

- Definition: The primary structure is the simplest and most fundamental level, referring to the exact linear sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain. It's akin to the order of letters in a word or sentence.

- Bonding: The only covalent bonds involved in defining the primary structure are the peptide bonds that link adjacent amino acid residues. These are strong amide bonds formed between the carboxyl group of one amino acid and the amino group of the next, with the elimination of water.

- Significance: The primary structure is the most crucial level of protein structure because it dictates all subsequent levels of folding. The unique sequence of amino acids contains all the intrinsic information necessary for the polypeptide chain to spontaneously (or with the aid of chaperones) fold into its stable, functional three-dimensional form.

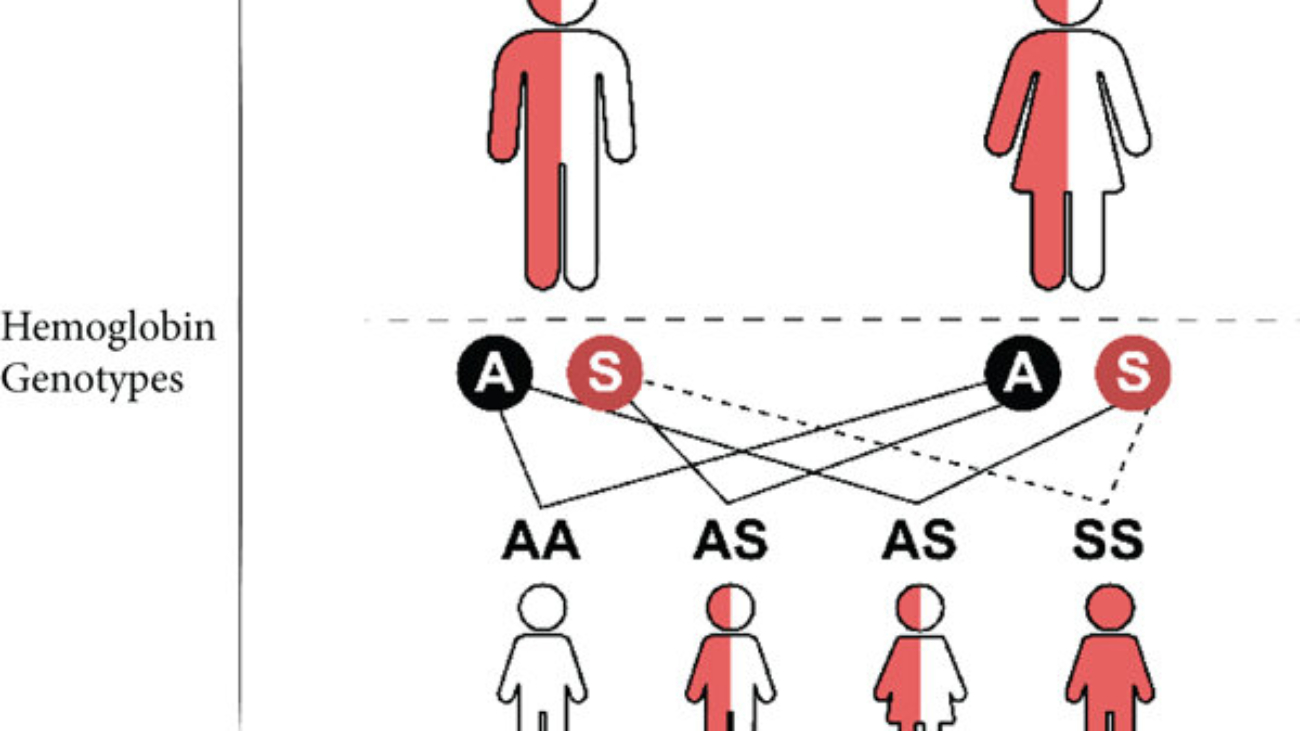

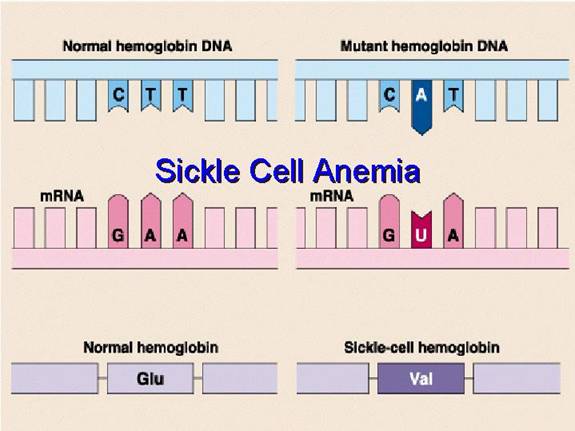

- A change in even a single amino acid (due to a gene mutation) can drastically alter the protein's higher-order structure and, consequently, its function. A classic example is sickle cell anemia, where a single amino acid substitution (Glutamate to Valine) in the beta-globin chain of hemoglobin leads to profound changes in red blood cell shape and oxygen transport capacity.

- Information Content: This level essentially contains the genetic "blueprint" or all the information needed for the protein to fold correctly into its native (functional) state.

2. Secondary Structure (2° Structure)

- Definition: Secondary structure refers to localized, regularly repeating conformations of the polypeptide chain. These structures are formed by hydrogen bonding solely between the atoms of the polypeptide backbone (specifically, the carbonyl oxygen and the amide hydrogen), not involving the R-groups at this level. These hydrogen bonds form regularly between residues that are close in the primary sequence.

- Stabilization: These structures are stabilized by an extensive network of hydrogen bonds between the carbonyl oxygen (C=O) of one peptide bond and the amide hydrogen (N-H) of another peptide bond.

Key Types: The two most common, stable, and well-defined types of secondary structure are:

a. Alpha-Helix (α-helix):

- Shape: A coiled, spiral structure resembling a right-handed screw (helical turn).

- Stabilization: Formed by hydrogen bonds that occur regularly between the carbonyl oxygen of residue n and the amide hydrogen of residue n+4 (i.e., four amino acids away along the backbone). These hydrogen bonds run roughly parallel to the helix axis.

- Characteristics:

- The R-groups of the amino acids project outward from the helix, minimizing steric hindrance and influencing interactions with the surrounding environment or other parts of the protein.

- Common in both globular and fibrous proteins.

- Certain amino acids like Proline (due to its rigid ring structure and lack of an available amide hydrogen for hydrogen bonding within the helix) and amino acids with bulky or similarly charged R-groups can disrupt alpha-helices.

- Examples: Abundant in keratin (in hair, nails, wool), and many globular proteins like myoglobin (an oxygen-storage protein).

b. Beta-Sheet (β-sheet):

- Shape: A pleated, sheet-like structure (hence "pleated sheet") formed by two or more extended polypeptide segments, called beta-strands, running alongside each other.

- Stabilization: Formed by hydrogen bonds between the carbonyl oxygen of one beta-strand and the amide hydrogen of an adjacent beta-strand. These hydrogen bonds run roughly perpendicular to the direction of the polypeptide chains.

- Orientation: Beta-sheets can be configured in two main ways:

- Parallel: Adjacent beta-strands run in the same N-to-C direction.

- Antiparallel: Adjacent beta-strands run in opposite N-to-C directions. Antiparallel sheets are generally considered more stable due to more optimal linear hydrogen bond geometry.

- Characteristics: The R-groups extend alternately above and below the plane of the sheet.

- Examples: Found in silk fibroin (gives silk its strength), and many proteins involved in immune responses or structural support like fatty acid binding proteins.

3. Tertiary Structure (3° Structure)

- Definition: Tertiary structure is the overall, elaborate three-dimensional shape or conformation of a single polypeptide chain. It describes how all the secondary structural elements (α-helices, β-sheets, and less ordered regions like turns and loops), along with random coil segments, are precisely folded and arranged relative to one another to form a compact, functional protein domain or a whole protein.

- Bonding/Interactions: Tertiary structure is stabilized by a diverse array of interactions, primarily non-covalent, occurring between the R-groups of amino acids. These interactions occur between amino acids that may be far apart in the primary sequence but are brought into close proximity by the folding process. Key interactions include:

- Hydrophobic Interactions: The primary driving force for protein folding. Nonpolar (hydrophobic) R-groups tend to cluster together in the interior of the protein, away from the aqueous cellular environment. This minimizes their contact with water and maximizes the entropy of the water molecules, leading to a more stable structure.

- Ionic Interactions (Salt Bridges): Electrostatic attractions between oppositely charged R-groups (e.g., between the negatively charged carboxyl group of an Aspartate and the positively charged amino group of a Lysine).

- Hydrogen Bonds: Formed between polar uncharged R-groups (e.g., between Serine's hydroxyl and Asparagine's amide group), or between polar R-groups and backbone atoms not already involved in secondary structure.

- Van der Waals Forces: Weak, transient attractive forces that arise from temporary fluctuations in electron distribution, occurring between all atoms that are in close proximity. While individually weak, their cumulative effect can be significant in the densely packed interior of a protein.

- Disulfide Bonds (Covalent): Unique strong covalent bonds formed by the oxidation of the sulfhydryl (−SH) groups of two Cysteine residues. These act as "molecular staples" to provide significant structural stability, particularly common in extracellular proteins exposed to oxidizing environments.

- Significance: The tertiary structure is paramount for the protein's biological function. The specific 3D arrangement creates the precise architecture necessary for:

- Active sites in enzymes for substrate binding and catalysis.

- Binding sites for ligands, cofactors, or other proteins.

- Structural motifs essential for molecular recognition and interaction.

Fibrous vs. Globular Proteins

(A classification based on overall 3D shape, largely determined by tertiary structure)

Fibrous Proteins

- Shape/Solubility: Elongated, rod-like structures; typically insoluble in water.

- Function: Primarily provide structural support, mechanical strength, and protection.

- Stabilization: Held together by strong intermolecular forces, often including numerous disulfide bonds.

- Examples: Keratin (hair, nails), Fibroin (silk), Collagen (connective tissue), Myosin (muscle).

Globular Proteins

- Shape/Solubility: Compact, spherical shape; typically soluble in water, forming colloids.

- Function: Perform diverse, dynamic roles like catalysis, transport, regulation, and immune defense.

- Stabilization: Maintained by non-covalent interactions, with hydrophobic R-groups buried inside.

- Examples: Albumin, Globulins (antibodies), Myoglobin, Insulin.

4. Quaternary Structure (4° Structure)

- Definition: Quaternary structure refers to the arrangement and interactions of multiple polypeptide chains (individual subunits) to form a larger, functional protein complex. It describes how these separate polypeptide units assemble in three-dimensional space.

- Important Note: Not all proteins have quaternary structure; it is only present in multi-subunit proteins (oligomeric proteins). Monomeric proteins (single polypeptide chain) have only primary, secondary, and tertiary structures.

- Bonding/Interactions: Similar to tertiary structure, quaternary structure is stabilized primarily by various non-covalent interactions between the R-groups of amino acids located at the interfaces of the different polypeptide chains. These include:

- Hydrophobic interactions

- Ionic interactions (salt bridges)

- Hydrogen bonds

- Van der Waals forces

- In some cases, disulfide bonds can also form between different polypeptide chains (interchain disulfide bonds), covalently linking them within the quaternary structure.

- Significance: The formation of quaternary structure often confers several advantages:

- Increased Complexity and Function: Allows for more intricate and highly regulated biological functions, often involving cooperativity or allosteric regulation.

- Enhanced Stability: Often enhances the overall stability and resistance to denaturation of the protein complex.

- Cooperation (Allostery): In some proteins (a prime example being hemoglobin), the binding of a ligand (like oxygen) to one subunit can induce conformational changes that influence the binding affinity or catalytic activity of other subunits within the same complex. This phenomenon is called allostery, crucial for finely tuning biological processes.

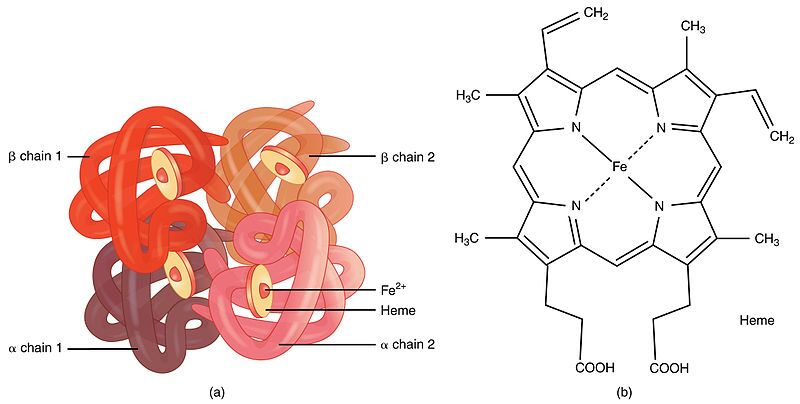

- Example: Hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells, is a classic example. It consists of four polypeptide subunits (two alpha chains and two beta chains), each binding an oxygen molecule. These four subunits interact to form the functional tetrameric protein.

Protein Folding and Denaturation

The biological function of a protein is precisely linked to its precise three-dimensional structure. The journey from a linear polypeptide chain to a biologically active, folded protein is a complex and highly regulated process known as protein folding. Conversely, the loss of this critical 3D structure, leading to loss of function, is termed denaturation.

Protein Folding

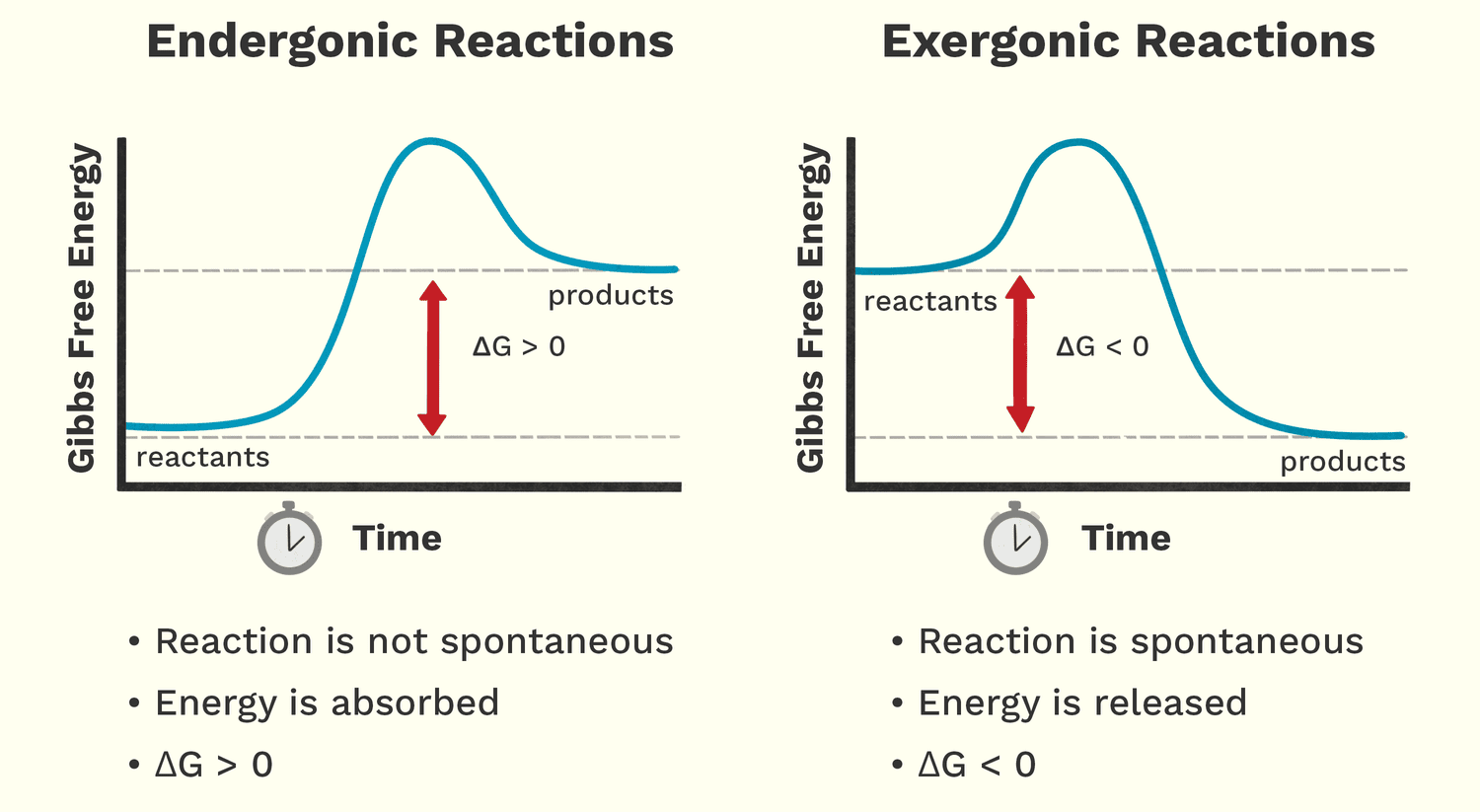

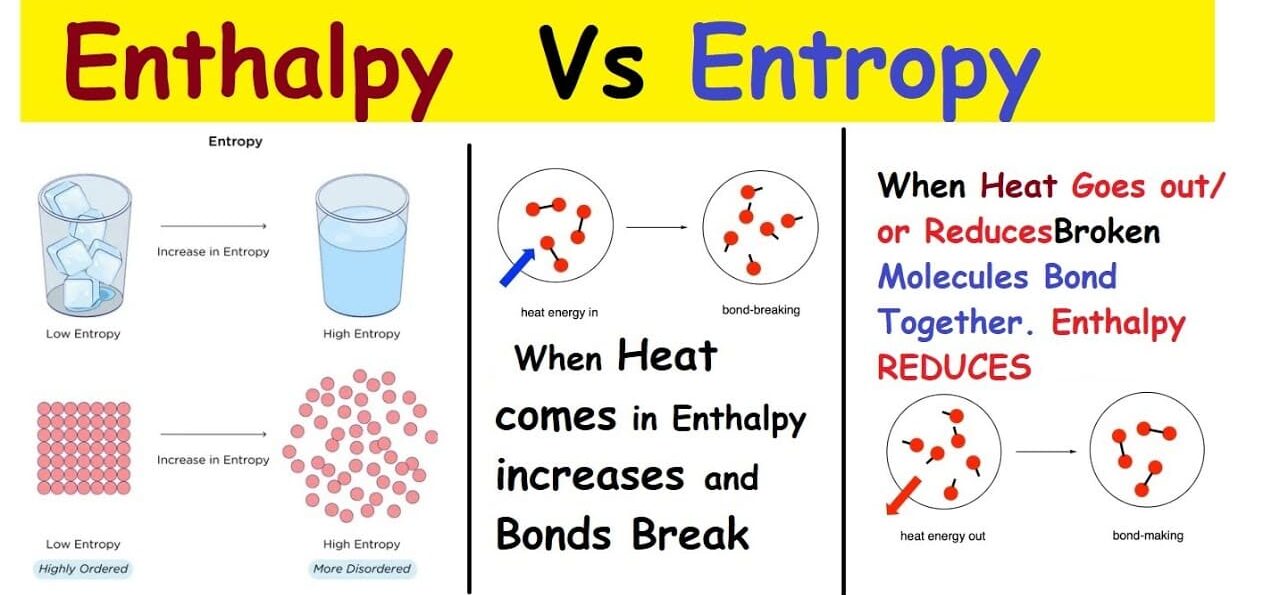

Definition: Protein folding is the spontaneous (or chaperon-assisted) process by which a newly synthesized or unfolded polypeptide chain acquires its intricate, specific, and functionally active three-dimensional conformation (its native state). This precise 3D structure is determined primarily by its primary amino acid sequence.

The "Folding Problem" and Energy Landscape:

The folding of a protein from a vast number of possible conformations to a single, stable native state is often referred to as the "folding problem." This process is generally understood in terms of an energy funnel or energy landscape:

- The unfolded polypeptide exists in a high-energy, high-entropy state with many possible conformations.

- As it folds, the protein progressively moves down an energy funnel, reducing its conformational entropy and lowering its free energy.

- The bottom of the funnel represents the native, most stable, and functional 3D structure.

- Intermediate states, or "misfolded" states, can exist, which are often thermodynamically less stable or kinetically trapped.

Driving Forces and Stabilizing Interactions for Folding:

The acquisition and maintenance of the native 3D structure are driven and stabilized by a combination of weak non-covalent interactions and, occasionally, strong covalent bonds. These interactions occur between amino acid R-groups and between backbone atoms:

- Hydrophobic Effect (The Primary Driver): This is arguably the most significant driving force for protein folding in aqueous environments.

- Mechanism: Nonpolar amino acid side chains (R-groups) tend to spontaneously cluster together in the interior of the protein, effectively "hiding" away from the surrounding aqueous (water) environment. This reduces the number of ordered water molecules that would otherwise surround these nonpolar groups (minimizing the unfavorable entropy loss of water).

- Effect: The overall result is an increase in the entropy of the solvent (water) and the formation of a compact hydrophobic core within the protein, minimizing the protein's surface area exposed to water.

- Formation of Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonds:

- Mechanism: Hydrogen bonds form extensively within the protein structure.

- Backbone-Backbone H-bonds: Critical for stabilizing secondary structures (α-helices and β-sheets) between the carbonyl oxygen (C=O) of one peptide bond and the amide hydrogen (N-H) of another.

- R-group-R-group H-bonds: Between polar uncharged amino acid side chains (e.g., Serine, Threonine, Asparagine, Glutamine).

- R-group-Backbone H-bonds: Between polar side chains and backbone atoms.

- Effect: These bonds contribute significantly to the overall stability and precise geometry of both secondary and tertiary structures.

- Ionic Interactions (Salt Bridges):

- Mechanism: Electrostatic attractions between oppositely charged R-groups of acidic amino acids (e.g., Aspartate, Glutamate) and basic amino acids (e.g., Lysine, Arginine, Histidine). These interactions often involve both charge attraction and hydrogen bonding components.

- Effect: Contribute to localized stability, particularly on the surface or within specific domains, and play a role in positioning functional groups.

- Van der Waals Interactions (London Dispersion Forces):

- Mechanism: Weak, short-range attractive forces that arise from transient, fluctuating dipoles in the electron clouds of all atoms when they are in very close proximity (typically 0.3-0.6 nm).

- Effect: Individually weak, but their cumulative effect can be substantial in the densely packed interior of a protein, where many atoms are in close contact, contributing significantly to the overall stability and packing efficiency.

- Disulfide Bonds (if present):

- Mechanism: These are strong covalent bonds formed by the oxidation of the sulfhydryl (−SH) groups of two Cysteine residues. They are often formed post-translationally in the endoplasmic reticulum (for secreted or transmembrane proteins) or in the extracellular space.

- Effect: Act as robust "molecular staples" that covalently link different parts of the polypeptide chain or even different polypeptide chains (in quaternary structures), providing significant additional stability and resistance to denaturation.

Molecular Chaperones (Chaperonins)

Definition: Molecular chaperones are a diverse and essential group of proteins that assist in the proper folding of other proteins. They do not become part of the final functional protein themselves; rather, they act as "helpers" or "escorts" in the folding process. They are particularly crucial under cellular stress conditions (like heat shock) or for newly synthesized proteins, guiding them through potentially hazardous folding pathways.

Role and Mechanisms:

- Preventing Misfolding and Aggregation:

- Mechanism: Chaperones bind specifically to exposed hydrophobic regions of nascent (newly synthesized and still folding) or partially unfolded proteins. These hydrophobic patches are normally buried in the interior of correctly folded proteins. By binding to them, chaperones prevent these sticky hydrophobic regions from interacting prematurely with other hydrophobic regions of the same or different proteins, which would lead to incorrect folding or aggregation into insoluble clumps.

- Effect: Ensures that the protein has sufficient time and a protected environment to explore proper folding pathways, preventing the formation of non-functional aggregates.

- Assisting Refolding:

- Mechanism: Some chaperones (e.g., the Hsp70 family) can bind to misfolded proteins, using ATP hydrolysis to induce conformational changes that can help pull apart aggregates or allow the misfolded protein another chance to refold correctly.

- Effect: Rescues misfolded proteins, restoring their function and preventing their accumulation, which can be toxic to the cell.

- Protecting from Stress (Heat Shock Proteins - HSPs):

- Mechanism: Many chaperones are constitutively expressed but their synthesis significantly increases in response to various cellular stresses, especially elevated temperatures. They are thus often referred to as "heat shock proteins" (HSPs). Heat stress can cause proteins to partially unfold, exposing hydrophobic regions and making them prone to aggregation. HSPs rapidly upregulate to combat this.

- Effect: HSPs act as a cellular defense mechanism, protecting existing proteins from heat-induced denaturation and facilitating the refolding of stress-damaged proteins, thereby maintaining cellular proteostasis (protein homeostasis).

Major Chaperone Families: Examples include the Hsp70 family (which binds to nascent chains), Hsp90 (involved in the maturation of signaling proteins), and chaperonins like GroEL/GroES (which provide an "isolation chamber" for protein folding).

Denaturation

Definition: Denaturation is the process by which a protein loses its specific, biologically active, native three-dimensional conformation. This loss of structure typically results in a loss of biological function.

Structural Changes:

- Denaturation primarily involves the disruption of the non-covalent interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, ionic interactions, Van der Waals forces) that stabilize the secondary, tertiary, and, if present, quaternary structures.

- Crucially, denaturation typically does not break the primary structure (peptide bonds). The amino acid sequence remains intact.

Consequences:

- Loss of Biological Activity: A denatured protein becomes biologically inactive because its specific active sites, binding domains, recognition surfaces, or structural integrity are lost or significantly altered.

- Reduced Solubility and Aggregation: The exposure of normally buried hydrophobic regions often leads to reduced solubility and a strong tendency for denatured proteins to aggregate into insoluble precipitates, which can be cytotoxic.

- Increased Susceptibility to Proteolysis: Unfolded proteins are often more susceptible to degradation by proteases.

Reversibility (Renaturation):

- Denaturation can sometimes be reversible (renaturation). If the denaturing agent is removed and the conditions are returned to normal (e.g., optimal pH, temperature), the protein may spontaneously refold into its native, functional state. This phenomenon, famously demonstrated by Christian Anfinsen with ribonuclease, showed that the primary sequence contains all the information needed for folding.

- However, severe or prolonged denaturation often leads to irreversible changes. Extensive aggregation or irreversible chemical modifications can prevent proper refolding, even after the denaturing agent is removed.

Denaturing Agents (Factors that Cause Denaturation)

Various physical and chemical agents can cause denaturation by interfering with the weak forces that maintain protein structure:

a. Heat

Mechanism: Increases kinetic energy, causing vibrations that disrupt weak non-covalent interactions like hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions. Effect: Causes unfolding, often irreversibly, like cooking an egg.

b. Extreme pH

Mechanism: Alters the ionization state of acidic and basic R-groups, disrupting crucial ionic bonds (salt bridges) and hydrogen bonding patterns. Effect: Causes charge repulsion and destabilizes the native conformation.

c. Organic Solvents

Mechanism: Less polar than water, these solvents (e.g., ethanol, acetone) disrupt and dissolve the internal hydrophobic core of proteins. Effect: Weakens the hydrophobic effect, leading to unfolding and precipitation.

d. Strong Detergents

Mechanism: Amphipathic molecules (e.g., SDS) bind to and disrupt hydrophobic regions, coating the protein with charge. Effect: Leads to complete unfolding into a random coil, useful in laboratory techniques.

e. Heavy Metal Ions

Mechanism: Ions like Pb²⁺ or Hg²⁺ react strongly with sulfhydryl (-SH) groups and charged R-groups. Effect: Disrupts disulfide and ionic bonds, often causing irreversible denaturation and enzyme inactivation.

f. Chaotropic Agents

Mechanism: Small molecules (e.g., urea, guanidinium chloride) disrupt the structure of water and form H-bonds with the protein. Effect: Weakens the hydrophobic effect and disrupts internal H-bonds, causing complete unfolding.

g. Mechanical Stress

Mechanism: Vigorous shaking, grinding, or shearing applies physical force that can break weak non-covalent interactions. Effect: Causes unfolding and aggregation as exposed hydrophobic regions interact, such as when whipping egg whites.

Protein Misfolding Diseases (Consequences of Folding Errors)

Despite the cellular machinery dedicated to ensuring proper protein folding, including a battery of molecular chaperones, errors can (and do) occur.

Proteins may fail to achieve their correct native state, or they may denature and subsequently refold improperly.

The accumulation of these misfolded proteins can have profound and often devastating consequences, leading to a wide array of severe diseases, prominently featuring neurodegenerative disorders. These conditions underscore the critical link between protein structure, function, and cellular health.

Mechanism of Disease: The Unifying Principles of Misfolding Pathology

While the specific proteins and affected tissues vary, a common set of pathological mechanisms underlies most protein misfolding diseases:

- Improper Folding:

- A protein either never successfully achieves its correct, lowest-energy native state during de novo synthesis. This can be due to genetic mutations that destabilize the native fold, overwhelmed chaperone systems, or unfavorable cellular environments.

- Alternatively, a correctly folded protein might denature (lose its native structure) due to stress or aging and then refold into an alternative, incorrect, and often stable conformation that lacks biological function.

- Aggregation:

- The Exposure of Sticky Surfaces: A hallmark of misfolded proteins is the exposure of normally buried hydrophobic regions or highly aggregation-prone segments. These exposed "sticky" surfaces facilitate abnormal intermolecular interactions.

- Self-Association: Misfolded proteins tend to self-associate through these exposed regions, leading to the formation of insoluble, ordered aggregates. These aggregates can range from small, soluble oligomers (which are often the most toxic species) to large, insoluble amyloid fibrils (characterized by a cross-β sheet structure) or amorphous inclusions.

- Reduced Degradation: The tightly packed, protease-resistant nature of these aggregates often renders them resistant to the cell's normal protein degradation pathways (e.g., the proteasome and lysosome/autophagy system), leading to their accumulation.

- Cellular Toxicity and Dysfunction:

- Interference with Proteostasis: The accumulation of misfolded proteins can overwhelm and impair the cell's protein quality control (proteostasis) machinery, leading to a vicious cycle where more proteins misfold and aggregate.

- Disruption of Organelle Function: Aggregates can physically interfere with the normal functioning of vital cellular organelles such as mitochondria (impairing energy production), endoplasmic reticulum (ER stress response), and lysosomes.

- Impairment of Transport: In neurons, aggregates can disrupt axonal transport, preventing essential molecules from reaching their destinations.

- Direct Toxicity: Soluble oligomers, in particular, are hypothesized to exert direct toxic effects, for example, by perforating membranes, disrupting synaptic function, or sequestering essential cellular components.

- Inflammation: Protein aggregates can also trigger inflammatory responses, further contributing to tissue damage.

- Cell Death: Ultimately, this cascade of dysfunction leads to cellular dysfunction and eventually cell death (apoptosis or necrosis), which is particularly devastating in post-mitotic cells like neurons. In the brain, this neuronal loss manifests as the clinical symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases.

Examples of Misfolding Diseases:

a. Sickle Cell Disease (SCD)

A Classic Example of a Point Mutation Leading to Aberrant Assembly

Misfolded/Mutated Protein: Hemoglobin (Hb). Specifically, a single-point mutation converts normal hemoglobin (HbA) to sickle hemoglobin (HbS) by replacing a polar glutamate with a nonpolar valine.

Mechanism: This substitution creates a "sticky" hydrophobic patch on the surface of deoxy-HbS. Under low oxygen conditions, these patches cause HbS molecules to polymerize into long, rigid, insoluble fibers that distort red blood cells into a rigid sickle shape.

Effect: The sickled cells are fragile (causing anemia) and rigid, leading to blockage of small blood vessels (vaso-occlusive crises), intense pain, and organ damage. It is a prime example of how a single amino acid change can have catastrophic physiological consequences.

b. Alzheimer's Disease (AD)

A Dual-Protein Pathology

Misfolded Proteins: Primarily involves two proteins: Beta-amyloid (Aβ) and Tau.

Mechanism: Aβ is a peptide that misfolds and aggregates extracellularly to form insoluble amyloid plaques between neurons. The Tau protein becomes hyperphosphorylated, detaches from microtubules, and aggregates intracellularly to form neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) inside neurons.

Effect: The accumulation of both plaques and tangles is thought to cause widespread neuronal dysfunction and death, leading to progressive cognitive decline, severe memory loss, and dementia.

c. Parkinson's Disease (PD)

Synucleinopathy

Misfolded Protein: Alpha-synuclein, a protein involved in synaptic vesicle regulation.

Mechanism: Alpha-synuclein misfolds and aggregates into intracellular inclusions called Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites. These aggregates primarily affect dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra region of the brain.

Effect: The progressive loss of these dopamine-producing neurons leads to a severe dopamine deficiency, causing the characteristic motor symptoms of Parkinson's, including tremor, rigidity, slowness of movement (bradykinesia), and postural instability.

d. Prion Diseases (TSEs)

Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies

Misfolded Protein: Prion protein (PrP). This disease is unique because the misfolded protein itself is infectious.

Mechanism: A normal cellular protein (PrPC) misfolds into an abnormal, protease-resistant isoform (PrPSc). This infectious PrPSc then acts as a template, forcing other normal PrPC molecules to adopt the misfolded conformation in a self-propagating chain reaction.

Effect: The accumulation of PrPSc aggregates causes widespread neuronal death and a "spongiform" (vacuolated) appearance in the brain, leading to rapidly progressive and fatal neurodegeneration. Examples include Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) in humans and "Mad Cow Disease" (BSE) in cattle.

e. Cystic Fibrosis (CF)

A Quality Control Error

Misfolded Protein: Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR), a chloride ion channel.

Mechanism: A common mutation (ΔF508) causes the CFTR protein to misfold. While it might still be partially functional, the cell's own quality control machinery in the endoplasmic reticulum recognizes the misfolded protein and targets it for premature degradation before it can reach the cell membrane.

Effect: The lack of functional CFTR channels at the cell surface impairs chloride ion transport, leading to thick, sticky mucus in the lungs, pancreas, and other organs, causing chronic infections, respiratory failure, and malabsorption.

Clinical Case Scenario: Sickle Cell Anemia

A 2-year-old boy from Mukono district is admitted to the hospital presenting with a constellation of acute symptoms: recurrent, excruciating severe bone pain affecting his hands, feet, and sternum for the past 3 days, accompanied by noticeable jaundice and profound fatigue. His parents report previous, similar episodes.

Laboratory findings on admission reveal:

- Haemoglobin: 6.2 g/dL (significantly below the normal range of 11-16 g/dL), indicative of severe anemia.

- Peripheral blood smear: Microscopic examination strikingly shows numerous sickled red blood cells, elongated and crescent-shaped, alongside normal discocytes.

- Liver function tests: Markedly elevated bilirubin, explaining the jaundice.

- Haemoglobin electrophoresis: Confirms the presence of a significantly increased percentage of sickled haemoglobin (HbS), with a reduced percentage of normal adult haemoglobin (HbA).

Based on these findings, a diagnosis of Vaso-occlusive crisis and severe anemia due to Sickle Cell Disease was made.

(a) Explain in detail the amino acid change that occurs in this patient's haemoglobin, highlighting the nature of the amino acids involved and the chemical basis of the mutation.

Detailed Explanation of the Amino Acid Change:

The genetic basis of Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) in this patient, as confirmed by the presence of HbS, lies in a single-point mutation within the gene encoding the beta-globin chain of hemoglobin. This seemingly minor alteration in the DNA sequence triggers a profound change at the protein level:

- Genetic Mutation: The primary cause is a substitution of a single nucleotide base within the DNA. Specifically, the triplet codon GAG (which codes for Glutamate) is mutated to GTG (which codes for Valine). This alteration in the genetic code is then transcribed into mRNA, leading to a changed codon from GAG to GUG.

- Amino Acid Substitution: This altered mRNA codon (GUG) during translation directs the ribosome to incorporate Valine instead of Glutamate at the sixth position of the beta-globin polypeptide chain.

- Nature of the Amino Acids Involved:

- Glutamate (Glu, E): In its physiological ionized state, glutamate is a polar, negatively charged (acidic) amino acid. Its side chain contains a carboxyl group (−COOH) that is deprotonated to −COO− at neutral pH, making it hydrophilic and capable of forming ionic bonds (salt bridges) and hydrogen bonds. Typically, glutamate residues are found on the surface of soluble proteins, interacting favorably with the aqueous cellular environment.

- Valine (Val, V): Valine, in contrast, is a nonpolar, hydrophobic amino acid. Its side chain consists of a branched hydrocarbon chain, which does not interact favorably with water. Consequently, valine residues are typically buried in the hydrophobic core of folded proteins, away from the aqueous environment.

- Chemical Basis of the Mutation and its Impact on Protein Surface:

- The crucial chemical change is the replacement of a hydrophilic, negatively charged amino acid (Glutamate) with a hydrophobic, uncharged amino acid (Valine) at a critical, solvent-exposed position on the surface of the beta-globin protein.

- This substitution creates a newly exposed hydrophobic patch on the surface of the beta-globin subunit when hemoglobin is in its deoxy (deoxygenated) state. This hydrophobic region is normally absent in HbA, where the glutamate residue at this position would facilitate favorable interactions with water. This subtle change in surface chemistry is the initial molecular trigger for the pathogenesis of SCD.

(b) Describe how this amino acid change affects haemoglobin function at the molecular level and leads to the clinical manifestations observed.

Molecular Mechanism and Clinical Manifestations:

The single amino acid substitution of Valine for Glutamate at position 6 of the beta-globin chain profoundly alters the molecular behavior of hemoglobin S (HbS), particularly under conditions of low oxygen. This chain of events directly explains the patient's clinical presentation:

- Conformational Change upon Deoxygenation:

- Normal hemoglobin (HbA) exists as a tetramer of two alpha (α) and two beta (β) subunits. Its affinity for oxygen changes with its conformational state: the "R-state" (relaxed, oxygenated) has high affinity, while the "T-state" (tense, deoxygenated) has low affinity.

- The Valine substitution in HbS has little effect when oxygen is bound (oxy-HbS). However, upon deoxygenation (e.g., when red blood cells release oxygen to tissues in capillaries), the HbS molecule undergoes a conformational change into its T-state. This conformational shift is critical because it causes the newly introduced hydrophobic valine residue at β6 to become exposed on the surface of the beta-globin subunit.

- Abnormal Hydrophobic Interaction and Polymerization:

- The exposed hydrophobic Valine at β6 on one deoxy-HbS molecule fits precisely into a complementary hydrophobic pocket on an adjacent deoxy-HbS molecule, specifically within the α-chain of another hemoglobin tetramer.

- This sets off a cascade of abnormal hydrophobic interactions between multiple deoxy-HbS molecules. These weak, non-covalent interactions drive the spontaneous self-assembly and polymerization of deoxy-HbS into long, rigid, insoluble fibers (often referred to as "sickle hemoglobin polymers" or "tactoids"). This process represents a severe form of protein aggregation.

- Red Blood Cell Sickling:

- The accumulation of these long, stiff HbS polymers distorts the internal structure of the red blood cell.

- This causes the red blood cell to lose its characteristic biconcave disc shape and become rigid, elongated, and crescent or sickle-shaped. This is the key morphological change observed on the peripheral smear.

- Clinical Manifestations Explained by Sickling:

- Vaso-occlusive Crisis (Severe Bone Pain):

- Mechanism: The rigid, sickled red blood cells cannot readily deform to pass through narrow blood vessels, particularly the microvasculature (capillaries and venules). They tend to clump together and physically obstruct blood flow.

- Effect: This leads to ischemia (reduced blood supply) and infarction (tissue death) in the affected tissues. In this patient, the severe bone pain in his hands, feet, and sternum (common sites in children) is a direct consequence of this vaso-occlusion depriving the bone marrow and bone tissue of oxygen and nutrients. This is the hallmark "sickle cell crisis."

- Severe Anemia (Haemoglobin = 6.2 g/dL, Fatigue):

- Mechanism: Sickled red blood cells are much more fragile than normal red blood cells and have a significantly shortened lifespan (10-20 days compared to 100-120 days for normal red cells). They are prematurely destroyed by the spleen and other parts of the reticuloendothelial system (extravascular hemolysis).

- Effect: This rapid destruction (hemolysis) outpaces the bone marrow's ability to produce new red blood cells, resulting in chronic and severe anemia. The patient's fatigue is a classic symptom of reduced oxygen-carrying capacity due to anemia.

- Jaundice and Elevated Bilirubin:

- Mechanism: The accelerated breakdown of red blood cells (hemolysis) releases large amounts of hemoglobin. Hemoglobin is catabolized into heme, which is then converted into bilirubin (an orange-yellow pigment).

- Effect: The liver, even if functioning normally, can be overwhelmed by the excessive production of bilirubin, leading to its accumulation in the blood. This results in jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes) and elevated bilirubin levels on liver function tests.

- Vaso-occlusive Crisis (Severe Bone Pain):

(c) Discuss the role of amino acid chemistry in potential therapeutic approaches to sickle cell disease.

Role of Amino Acid Chemistry in Therapeutic Approaches to SCD:

Understanding the precise amino acid change and its chemical consequences is fundamental to designing and developing targeted therapies for SCD. Many current and emerging treatments aim to counteract the effects of the Valine substitution by modulating protein-protein interactions, altering the oxygen affinity of HbS, or promoting the production of alternative hemoglobin forms.

- Preventing HbS Polymerization (Targeting Hydrophobic Interactions):

- Principle: The core problem is the abnormal hydrophobic interaction driven by β6-Valine. Therapies can aim to interfere with this interaction.

- Approaches: Developing drugs that bind to the HbS molecule at the β6-Valine site or the complementary binding pocket.

- Example: Voxelotor (Oxbryta) is a recently approved drug that works by binding to the alpha-globin chains of HbS, stabilizing hemoglobin in its high-oxygen-affinity (R-state) conformation. By doing so, it reduces the amount of deoxy-HbS available to polymerize, thereby inhibiting sickling.

- Increasing Haemoglobin Oxygen Affinity (Modulating Allostery):

- Principle: If HbS stays oxygenated for longer, it won't deoxygenate and polymerize. The β6-Valine only becomes problematic in the deoxy-state.

- Approaches: Drugs that bind to HbS and shift its oxygen dissociation curve to the left, increasing its affinity for oxygen. Voxelotor, as mentioned above, achieves this.

- Promoting Fetal Haemoglobin (HbF) Production:

- Principle: Fetal hemoglobin (α2γ2) does not contain the β-globin chain and thus lacks the β6-Valine mutation. It does not sickle. Increasing its production dilutes HbS and prevents sickling.

- Approaches: Hydroxyurea (Hydroxycarbamide) is a small molecule that reactivates γ-globin gene expression, leading to increased HbF synthesis. The increased presence of non-sickling HbF reduces the concentration of HbS, thereby raising the critical concentration for sickling and diminishing polymerization.

- Reducing Cellular Dehydration (Modulating Ion Transport):

- Principle: Dehydration of red blood cells increases the intracellular concentration of HbS, promoting polymerization.

- Approaches: Investigational drugs that aim to inhibit ion transporters like the KCl cotransporter, thereby reducing cellular water loss.

In summary, a deep understanding of the chemical properties of amino acids and how their interactions govern protein structure and function is paramount. Therapies for SCD leverage this knowledge to develop molecules that either directly prevent the abnormal hydrophobic interactions (like Voxelotor), indirectly modify the cellular environment to reduce sickling (like Hydroxyurea), or, in the future, correct the genetic error at its source.

Clinical Case Scenario: A Progressive Cognitive Decline

Mrs. Eleanor Vance, an 82-year-old retired schoolteacher, is brought to the neurology clinic by her worried daughter. Over the past 5 years, Mrs. Vance has exhibited a gradual and progressive decline in her cognitive abilities. Initially, it was subtle memory lapses, such as forgetting names or misplacing keys. More recently, she has struggled with complex tasks like managing her finances, preparing meals, and following conversations. Her daughter reports that Mrs. Vance frequently repeats herself, gets disoriented in familiar surroundings, and occasionally exhibits mood swings and agitation. There is no history of stroke or significant head trauma. A physical and neurological examination reveals no focal deficits, but a mini-mental state examination (MMSE) score indicates significant cognitive impairment. Brain imaging (MRI) shows generalized cerebral atrophy, particularly pronounced in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex, but no evidence of tumors or vascular lesions.

Based on the clinical presentation and diagnostic findings, a presumptive diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease is made.

Questions related to Protein Misfolding in Alzheimer's Disease:

(a) Alzheimer's Disease is characterized by the accumulation of two distinct types of protein aggregates: amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. For amyloid plaques, identify the primary protein involved, describe its origin, and explain how its misfolding and aggregation contribute to the pathology.

Primary Protein and Origin: