Body Regions, Abdominal Quadrants & Terminology

I. Introduction to Body Regions

The human body is divided into various anatomical regions to facilitate precise localization, communication, and study. This regional approach helps in systematically understanding the organization of structures (muscles, bones, nerves, vessels) and organs, which is crucial for physical examination, diagnosis, and surgical interventions.

The body is broadly divided into two main parts:

- Axial Region: Forms the main axis of the body, comprising the head, neck, and trunk.

- Appendicular Region: Consists of the limbs (appendages) attached to the axial skeleton.

II. The Axial Region

The axial region forms the central core of the body and includes the most vital organs for survival.

A. Head (Caput):

- Boundaries:

- Superior: Vertex (highest point of the skull).

- Inferior: Mandible (jawbone) and the base of the skull, connecting to the neck.

- Anterior: Face, extending from the forehead to the chin.

- Posterior: Occipital region.

- Lateral: Temporal and parietal regions.

- Key Features/Subdivisions:

- Cranium (Skull): Encloses and protects the brain. Subdivided into:

- Frontal: Forehead.

- Parietal: Sides and roof of the skull.

- Temporal: Sides of the head, inferior to parietal.

- Occipital: Back and base of the skull.

- Face (Facies): Contains sensory organs and the entry points for the digestive and respiratory systems. Subdivided into:

- Orbital: Around the eyes.

- Nasal: Nose region.

- Oral (Buccal): Mouth and cheeks.

- Mental: Chin.

- Zygomatic: Cheekbones.

- Auricular: Ear region.

- Cranium (Skull): Encloses and protects the brain. Subdivided into:

B. Neck (Cervix):

- Boundaries:

- Superior: Base of the skull and inferior border of the mandible.

- Inferior: Superior border of the clavicles (collarbones) and the superior border of the sternum (breastbone), extending posteriorly to the first thoracic vertebra.

- Anterior: From chin to suprasternal notch.

- Posterior: From occipital region to upper back.

- Key Features/Subdivisions:

- Anterior Cervical Region: Contains the trachea, larynx, thyroid gland, major blood vessels (carotid arteries, jugular veins), and neck muscles.

- Posterior Cervical Region (Nuchal Region): Contains the cervical vertebrae and deep back muscles.

- Lateral Cervical Region: Defined by the

sternocleidomastoidmuscle, dividing it into anterior and posterior triangles.

C. Trunk (Truncus):

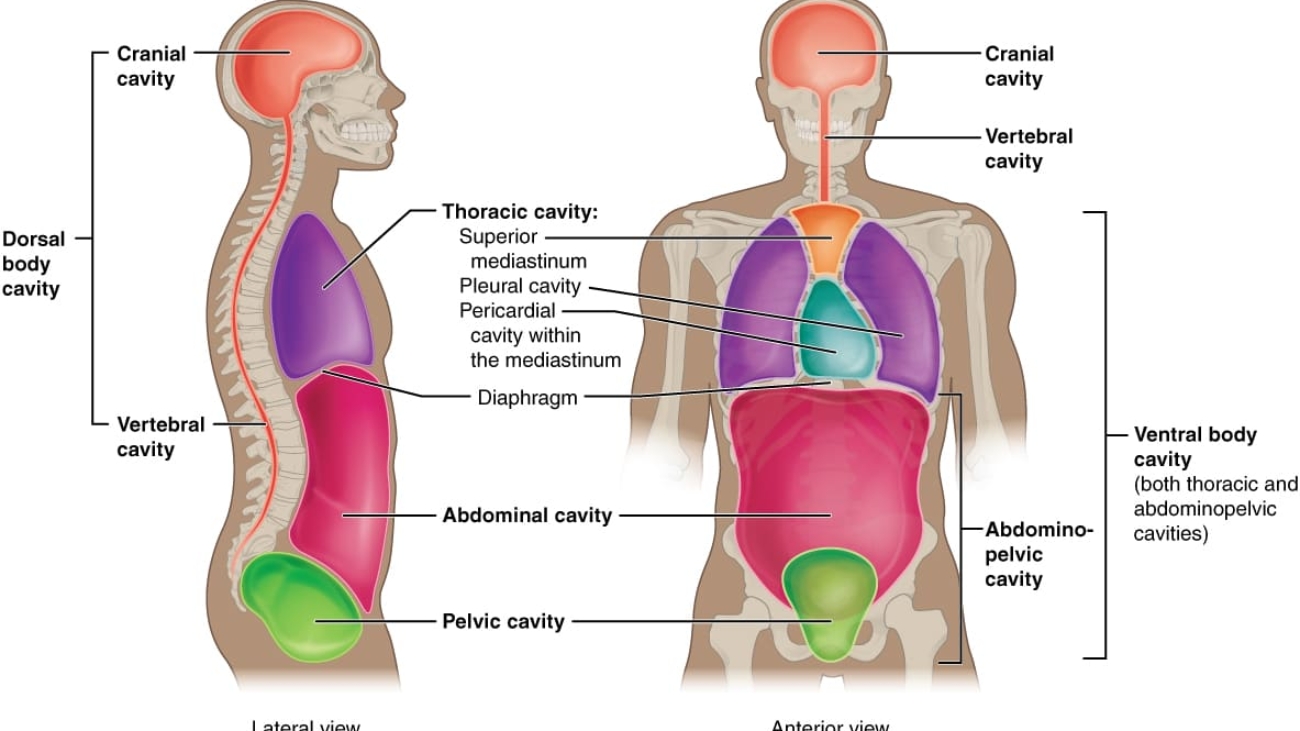

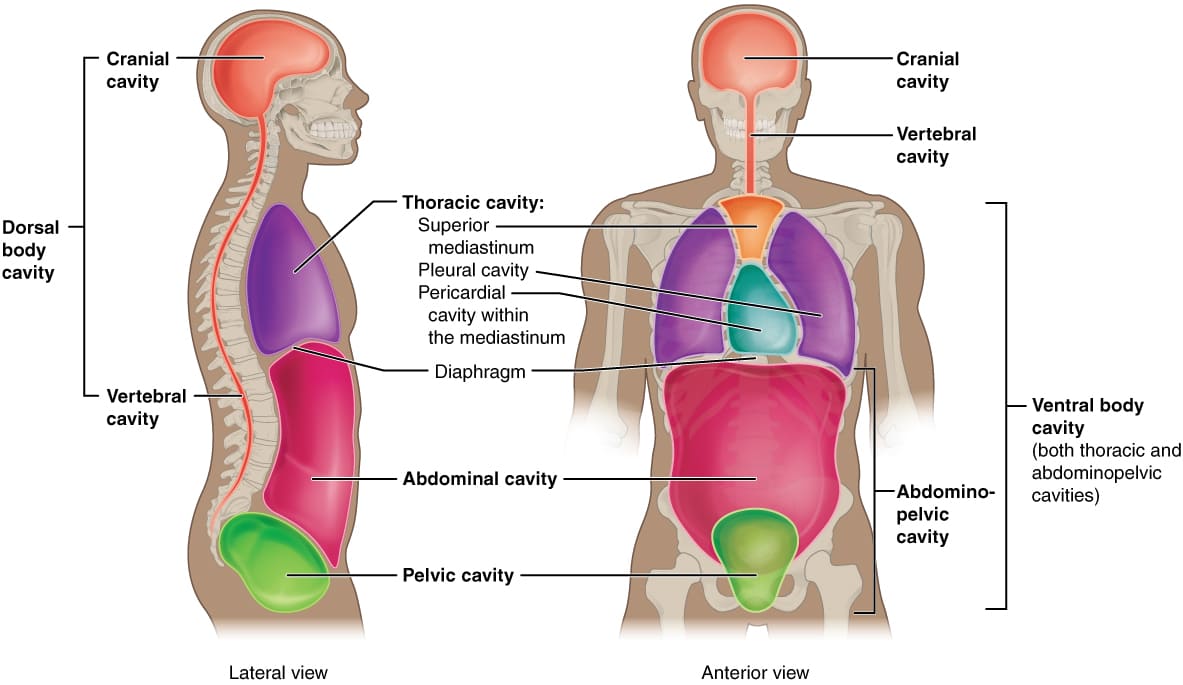

The trunk is the largest region of the axial body, divided into the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis.

1. Thorax (Chest):

- Boundaries:

- Superior: Thoracic inlet (superior aperture of the thorax), continuous with the neck.

- Inferior: Diaphragm, separating it from the abdomen.

- Anterior: Sternum and costal cartilages.

- Posterior: Thoracic vertebrae.

- Lateral: Ribs and intercostal muscles.

- Key Features/Subdivisions:

- Thoracic Wall: Provides bony protection (rib cage).

- Thoracic Cavity: Contains the heart, lungs, great vessels, esophagus, trachea, and thymus gland.

- Breasts (Mammary Region): Located anteriorly, superficial to the pectoralis major muscle.

- Clinical Significance: Houses vital respiratory and circulatory organs. Site for respiratory and cardiac examinations, chest trauma, and breast pathologies.

2. Abdomen:

- Boundaries:

- Superior: Diaphragm.

- Inferior: Continuous with the pelvis at the level of the pelvic inlet.

- Anterior/Lateral: Abdominal wall muscles (rectus abdominis, obliques, transversus abdominis).

- Posterior: Lumbar vertebrae and associated muscles.

- Key Features/Subdivisions:

- Abdominal Cavity: Contains most of the digestive organs, spleen, kidneys, adrenal glands.

- Abdominal Wall: Muscular layers provide support and protect organs.

- Clinical Significance: Site of many digestive, urinary, and reproductive system pathologies. Crucial for abdominal examination, assessment of pain, and surgical access.

3. Pelvis:

- Boundaries:

- Superior: Pelvic inlet (linea terminalis), continuous with the abdomen.

- Inferior: Pelvic outlet (pelvic diaphragm/floor).

- Lateral: Hip bones (ilium, ischium, pubis).

- Posterior: Sacrum and coccyx.

- Key Features/Subdivisions:

- Pelvic Cavity: Contains the urinary bladder, rectum, and reproductive organs.

- Perineum: Region inferior to the pelvic diaphragm, containing external genitalia and anal canal.

- Clinical Significance: Houses urinary, reproductive, and terminal digestive organs. Important for urological, gynecological, and colorectal examinations.

III. The Appendicular Region

The appendicular region consists of the upper and lower limbs, specialized for movement and manipulation.

A. Upper Limb (Extremitas Superior):

- Boundaries: Attached to the axial skeleton via the pectoral girdle (scapula and clavicle).

- Key Features/Subdivisions:

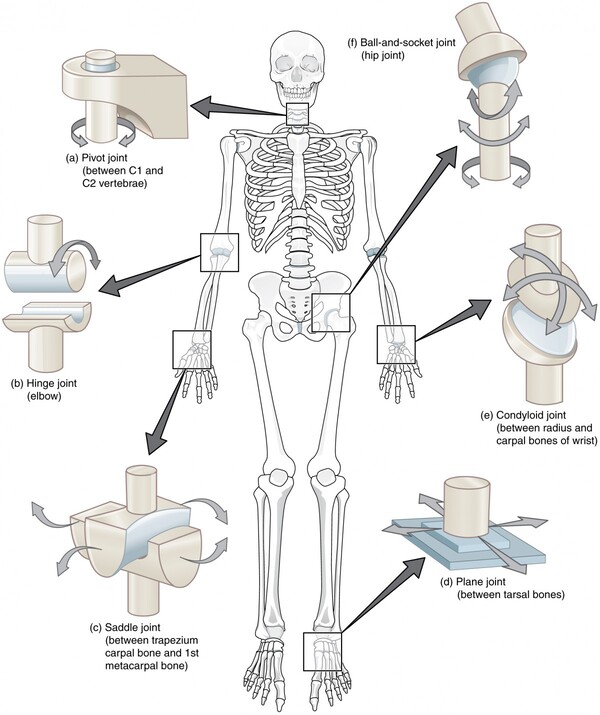

- Shoulder (Deltoid Region): Proximal attachment to the trunk, site of glenohumeral joint.

- Arm (Brachium): Between shoulder and elbow. Contains humerus.

- Elbow (Cubital Region): Joint between arm and forearm.

- Forearm (Antebrachium): Between elbow and wrist. Contains radius and ulna.

- Wrist (Carpus): Joint between forearm and hand.

- Hand (Manus): Distal end, highly mobile and manipulative. Subdivided into:

- Palm (Palmar/Volar aspect): Anterior surface.

- Dorsum (Dorsal aspect): Posterior surface.

- Digits (Fingers): Phalanges.

- Clinical Significance: High mobility, frequent site of fractures, dislocations, nerve entrapments (e.g., carpal tunnel syndrome), and vascular issues.

B. Lower Limb (Extremitas Inferior):

- Boundaries: Attached to the axial skeleton via the pelvic girdle (hip bones).

- Key Features/Subdivisions:

- Hip (Coxal Region): Proximal attachment to the trunk, site of hip joint.

- Thigh (Femoral Region): Between hip and knee. Contains femur.

- Knee (Patellar/Popliteal Region): Joint between thigh and leg.

- Patellar: Anterior aspect (kneecap).

- Popliteal: Posterior aspect (back of knee).

- Leg (Crus): Between knee and ankle. Contains tibia and fibula.

- Ankle (Tarsus): Joint between leg and foot.

- Foot (Pes): Distal end, weight-bearing and propulsion. Subdivided into:

- Dorsum: Superior surface.

- Plantar: Inferior surface (sole).

- Digits (Toes): Phalanges.

- Clinical Significance: Weight-bearing, locomotion. Common site for fractures, sprains (ankle), degenerative joint disease (knee, hip), and vascular conditions (e.g., DVT).

| Region | Subdivision(s) | Key Bony/Muscular Boundaries | Key Contents/Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axial: Head | Cranium, Face | Skull bones, Mandible | Brain, Sense organs (eyes, ears, nose, mouth) |

| Axial: Neck | Anterior, Posterior, Lateral | Base of skull, Mandible, Clavicles, Sternum, C7 vertebra | Trachea, Larynx, Thyroid, Carotids, Jugulars, Cervical spine |

| Axial: Trunk (Thorax) | Thorax | Rib cage, Sternum, Thoracic vertebrae, Diaphragm (inferior) | Heart, Lungs, Esophagus, Trachea, Great vessels, Breasts |

| Axial: Trunk (Abdomen) | Abdomen | Diaphragm (superior), Pelvic inlet (inferior), Abdominal muscles, Lumbar vertebrae | Most digestive organs, Kidneys, Spleen, Adrenals |

| Axial: Trunk (Pelvis) | Pelvis | Pelvic inlet (superior), Pelvic floor (inferior), Hip bones, Sacrum, Coccyx | Bladder, Rectum, Reproductive organs |

| Appendicular: Upper Limb | Shoulder, Arm, Elbow, Forearm, Wrist, Hand | Pectoral girdle, Humerus, Radius, Ulna, Carpals, Metacarpals, Phalanges | Muscles, Nerves (e.g., Brachial plexus), Vessels (e.g., Brachial artery) |

| Appendicular: Lower Limb | Hip, Thigh, Knee, Leg, Ankle, Foot | Pelvic girdle, Femur, Patella, Tibia, Fibula, Tarsals, Metatarsals, Phalanges | Muscles, Nerves (e.g., Sciatic nerve), Vessels (e.g., Femoral artery) |

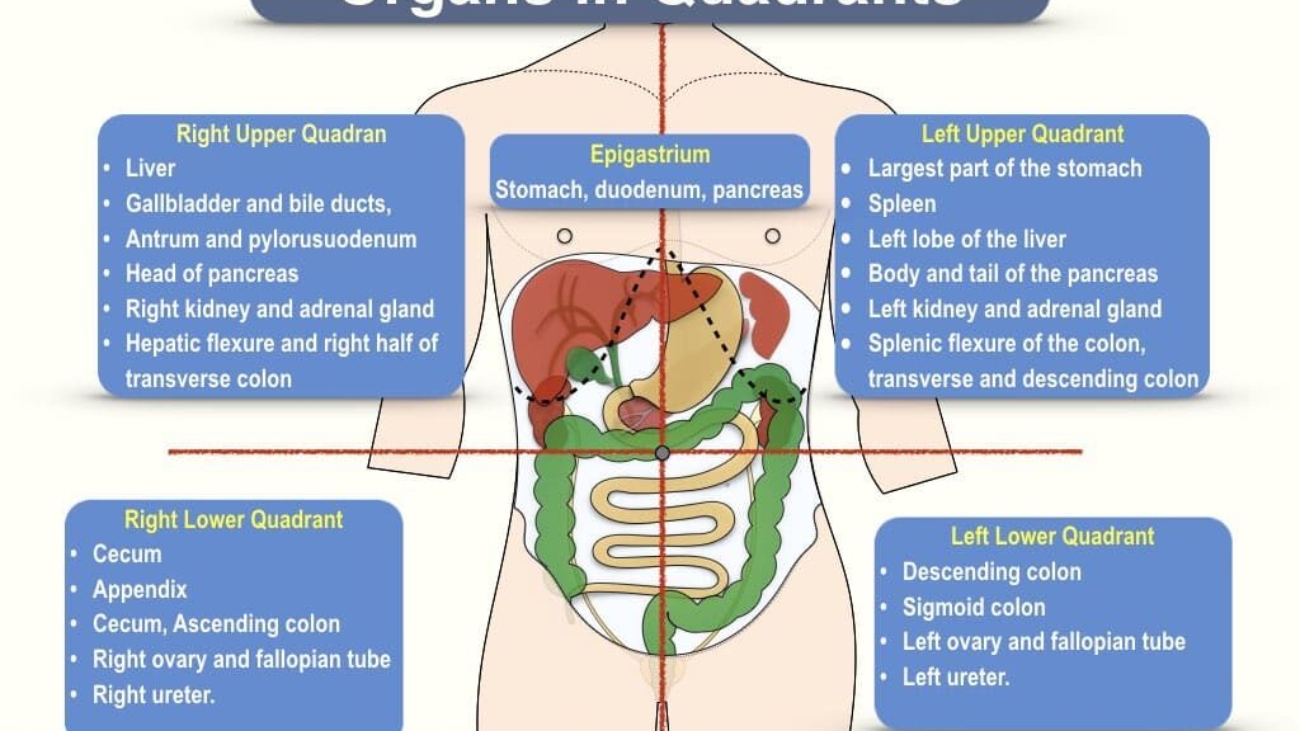

IV. Abdominal Quadrants

The abdominal cavity is a large and complex space. For simplicity and quick communication in clinical settings (especially during physical examinations or when discussing pain location), it is often divided into four quadrants. This division is less precise than the nine regions but provides a useful initial localization.

A. Delineation of Quadrants:

The abdomen is divided into four quadrants by two imaginary perpendicular lines that intersect at the umbilicus (navel):

- Median Plane (Mid-sagittal Plane): A vertical line that passes through the sternum, umbilicus, and pubic symphysis, dividing the abdomen into left and right halves.

- Transumbilical Plane (Transverse Plane): A horizontal line that passes through the umbilicus, dividing the abdomen into upper and lower halves.

1. Right Upper Quadrant (RUQ):

- Liver: Right lobe (majority).

- Gallbladder: Often the source of RUQ pain (cholecystitis).

- Duodenum: First part of the small intestine.

- Head of Pancreas: The most superior part of the pancreas.

- Right Kidney: Upper part.

- Right Adrenal Gland.

- Hepatic Flexure of Colon: The bend between the ascending and transverse colon.

- Pylorus of Stomach: Distal part of the stomach.

2. Left Upper Quadrant (LUQ):

- Stomach: Majority of the stomach.

- Spleen: Located posterolaterally, susceptible to injury.

- Pancreas: Body and tail.

- Liver: Small portion of the left lobe.

- Left Kidney: Upper part.

- Left Adrenal Gland.

- Jejunum and Proximal Ileum: Parts of the small intestine.

- Splenic Flexure of Colon: The bend between the transverse and descending colon.

3. Right Lower Quadrant (RLQ):

- Cecum: First part of the large intestine.

- Appendix: Attached to the cecum, classic site of appendicitis pain.

- Ascending Colon: Lower part.

- Ileum: Distal part of the small intestine.

- Right Ovary and Fallopian Tube (Females).

- Right Ureter.

- Right Spermatic Cord (Males).

- Part of the Urinary Bladder (when distended).

4. Left Lower Quadrant (LLQ):

- Descending Colon.

- Sigmoid Colon: S-shaped part of the large intestine, common site of diverticulitis pain.

- Left Ovary and Fallopian Tube (Females).

- Left Ureter.

- Left Spermatic Cord (Males).

- Part of the Urinary Bladder (when distended).

V. Abdominal Regions

For a more precise anatomical and clinical description, the abdomen is further divided into nine regions. This system is particularly useful for detailing localized pain, masses, or organ abnormalities.

A. Delineation of Regions:

The nine abdominal regions are created by two imaginary horizontal (transverse) planes and two imaginary vertical (sagittal/midclavicular) planes.

- Horizontal (Transverse) Planes:

- Subcostal Plane (Superior Transverse Line): Passes inferior to the lowest part of the costal margins (rib cage), typically at the level of the 10th costal cartilage or the third lumbar vertebra (L3).

- Transtubercular Plane (Inferior Transverse Line): Passes between the tubercles of the iliac crests (prominent points on the top of the hip bones), typically at the level of the fifth lumbar vertebra (L5).

- Vertical (Sagittal/Midclavicular) Planes:

- Right Midclavicular Line: Extends vertically downward from the midpoint of the right clavicle to the middle of the inguinal ligament.

- Left Midclavicular Line: Extends vertically downward from the midpoint of the left clavicle to the middle of the inguinal ligament.

B. The Nine Abdominal Regions and Their Major Organ Contents:

1. Epigastric Region (Upper Central):

Location: Superior to the umbilicus, between the right and left midclavicular lines, above the subcostal plane.

Contents: Stomach (Pyloric part), Duodenum (First part), Pancreas (Body), Liver (Left lobe), Aorta (Abdominal aorta), Inferior Vena Cava (IVC).

2. Umbilical Region (Central):

Location: Centered around the umbilicus, between the right and left midclavicular lines, between the subcostal and transtubercular planes.

Contents: Small Intestine (Jejunum and Ileum), Transverse Colon (Middle part), Kidneys (Medial parts), Ureters (Upper parts), Great Vessels (Aorta, IVC bifurcation).

3. Hypogastric (Pubic) Region (Lower Central):

Location: Inferior to the umbilicus, between the right and left midclavicular lines, below the transtubercular plane.

Contents: Urinary Bladder (when full), Small Intestine (Coils of ileum), Sigmoid Colon, Uterus (Females, gravid), Rectum (upper part).

4. Right Hypochondriac Region (Upper Right Lateral):

Location: Superior to the subcostal plane, lateral to the right midclavicular line.

Contents: Liver (Right lobe majority), Gallbladder, Right Kidney (Upper part), Duodenum (Part of it), Hepatic Flexure of Colon.

5. Left Hypochondriac Region (Upper Left Lateral):

Location: Superior to the subcostal plane, lateral to the left midclavicular line.

Contents: Spleen, Stomach (Fundus and body), Pancreas (Tail), Left Kidney (Upper part), Splenic Flexure of Colon, Part of Transverse Colon.

6. Right Lumbar (Flank) Region (Middle Right Lateral):

Location: Between the subcostal and transtubercular planes, lateral to the right midclavicular line.

Contents: Ascending Colon, Right Kidney (Lower part), Small Intestine (Coils of small bowel).

7. Left Lumbar (Flank) Region (Middle Left Lateral):

Location: Between the subcostal and transtubercular planes, lateral to the left midclavicular line.

Contents: Descending Colon, Left Kidney (Lower part), Small Intestine (Coils of small bowel).

8. Right Iliac (Inguinal) Region (Lower Right Lateral):

Location: Inferior to the transtubercular plane, lateral to the right midclavicular line.

Contents: Cecum, Appendix (McBurney's point), Distal Ileum, Right Ovary/Fallopian Tube (F), Right Spermatic Cord (M).

9. Left Iliac (Inguinal) Region (Lower Left Lateral):

Location: Inferior to the transtubercular plane, lateral to the left midclavicular line.

Contents: Sigmoid Colon, Left Ovary/Fallopian Tube (F), Left Spermatic Cord (M).

VI. Clinical Significance of Abdominal Quadrants and Regions

The division of the abdomen into quadrants and regions is not merely an academic exercise; it is a fundamental tool in clinical medicine, essential for clear communication, accurate diagnosis, and effective treatment.

A. Diagnostic Purposes:

- Localization of Symptoms:

- Pain: The most common symptom prompting abdominal assessment. Localizing pain to a specific quadrant or region significantly narrows down the differential diagnosis.

- Example: Right Lower Quadrant (RLQ) pain with migration from the umbilical region strongly suggests appendicitis.

- Example: Right Upper Quadrant (RUQ) pain, especially post-prandial, is characteristic of cholecystitis (gallbladder inflammation).

- Example: Left Lower Quadrant (LLQ) pain in an older adult often points to diverticulitis.

- Example: Epigastric pain can indicate gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, or even cardiac issues (referred pain).

- Tenderness/Rebound Tenderness: Indicates inflammation or irritation of underlying organs or peritoneum. Precise localization helps identify the affected structure.

- Masses/Swelling: Identifying a palpable mass in a specific region helps determine its potential origin (e.g., enlarged liver in RUQ, splenic enlargement in LUQ, ovarian cyst in iliac regions).

- Referred Pain: Knowledge of organ innervation patterns helps understand how pain from one organ can be perceived in a distant body region. For instance, diaphragmatic irritation (e.g., from a ruptured spleen or subphrenic abscess) can cause pain referred to the shoulder (due to phrenic nerve irritation).

- Pain: The most common symptom prompting abdominal assessment. Localizing pain to a specific quadrant or region significantly narrows down the differential diagnosis.

- Differential Diagnosis: Each quadrant/region has a characteristic set of organs. Knowing these allows clinicians to quickly generate a list of possible conditions based on the patient's presenting symptoms.

- Example: A patient presenting with fever and RUQ pain will prompt consideration of cholecystitis, hepatitis, liver abscess, or ascending cholangitis, among others.

B. Physical Examination:

- Systematic Approach: Quadrants and regions provide a systematic framework for conducting a thorough abdominal examination (inspection, auscultation, percussion, palpation).

- Inspection: Observing for distension, scars, rashes, pulsations, hernias in specific areas.

- Auscultation: Listening for bowel sounds in all four quadrants to assess bowel motility.

- Percussion: Tapping over regions to identify organ size (e.g., liver span in RUQ), presence of fluid (ascites), or gas (tympanitic sound over bowel).

- Palpation: Gently and deeply pressing into each region to assess for tenderness, masses, organomegaly (enlarged organs), or guarding.

- Documentation: Provides a standardized language for documenting findings, ensuring consistency and clarity among healthcare providers.

C. Surgical Planning and Procedures:

- Incision Placement: Surgeons use regional anatomy to plan optimal incision sites to access specific organs while minimizing damage to surrounding structures.

- Example: A McBurney incision for appendectomy in the RLQ, or a subcostal incision for gallbladder removal in the RUQ.

- Organ Identification: During surgery, knowledge of regional anatomy helps surgeons quickly identify and differentiate organs.

- Endoscopic Procedures: Guiding instruments during laparoscopy or endoscopy relies on understanding the spatial relationships of abdominal contents within these regions.

- Biopsy and Aspiration: Precise localization ensures that biopsies (e.g., liver biopsy) or fluid aspirations (e.g., paracentesis) are performed safely and effectively.

D. Anatomical Teaching and Learning:

- Simplification of Complexity: Breaking down the vast abdominal cavity into smaller, manageable units makes it easier for students to learn and recall organ locations.

- Foundation for Advanced Concepts: A solid understanding of these basic regional divisions is crucial before delving into more complex anatomical relationships and disease processes.

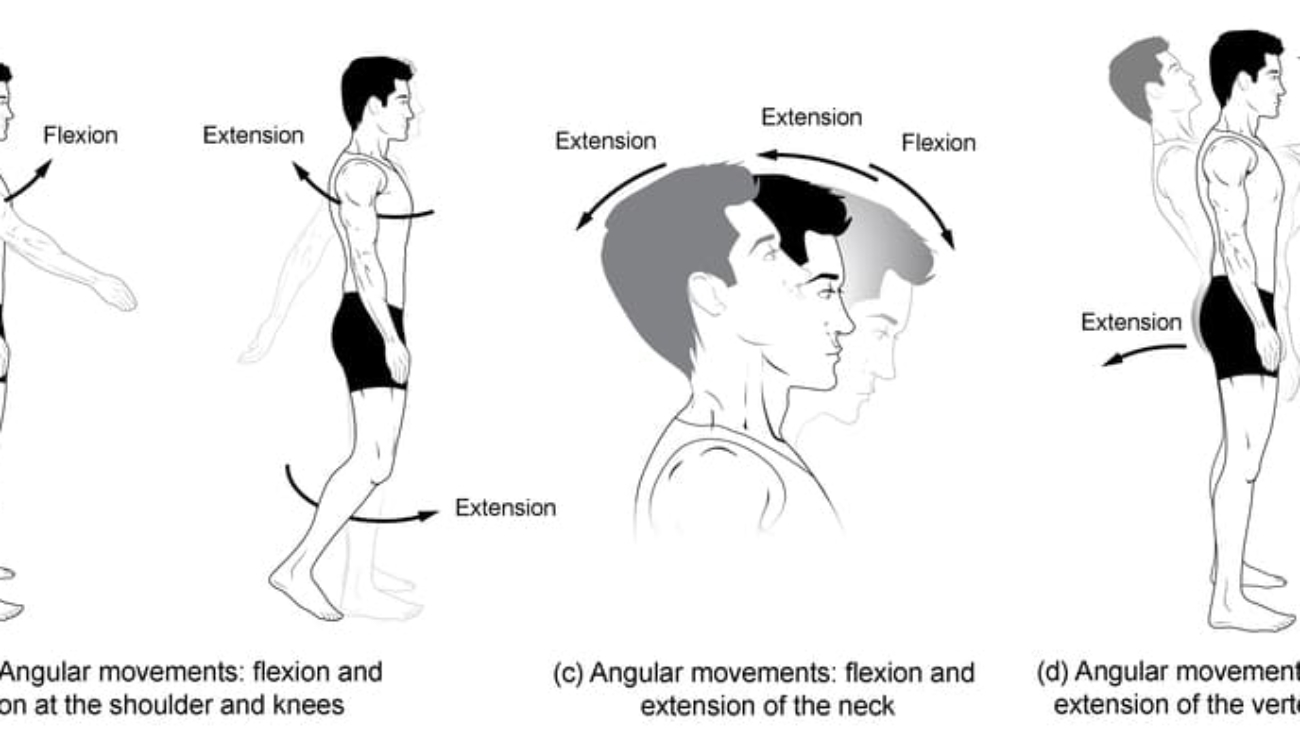

VII. Utilizing Appropriate Anatomical Terminology

Accurate and consistent use of anatomical terminology is paramount in healthcare for effective communication, avoiding ambiguity, and ensuring patient safety.

A. General Principles of Anatomical Language:

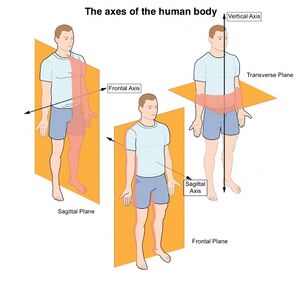

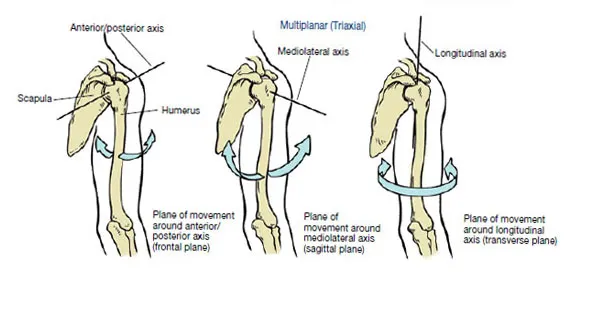

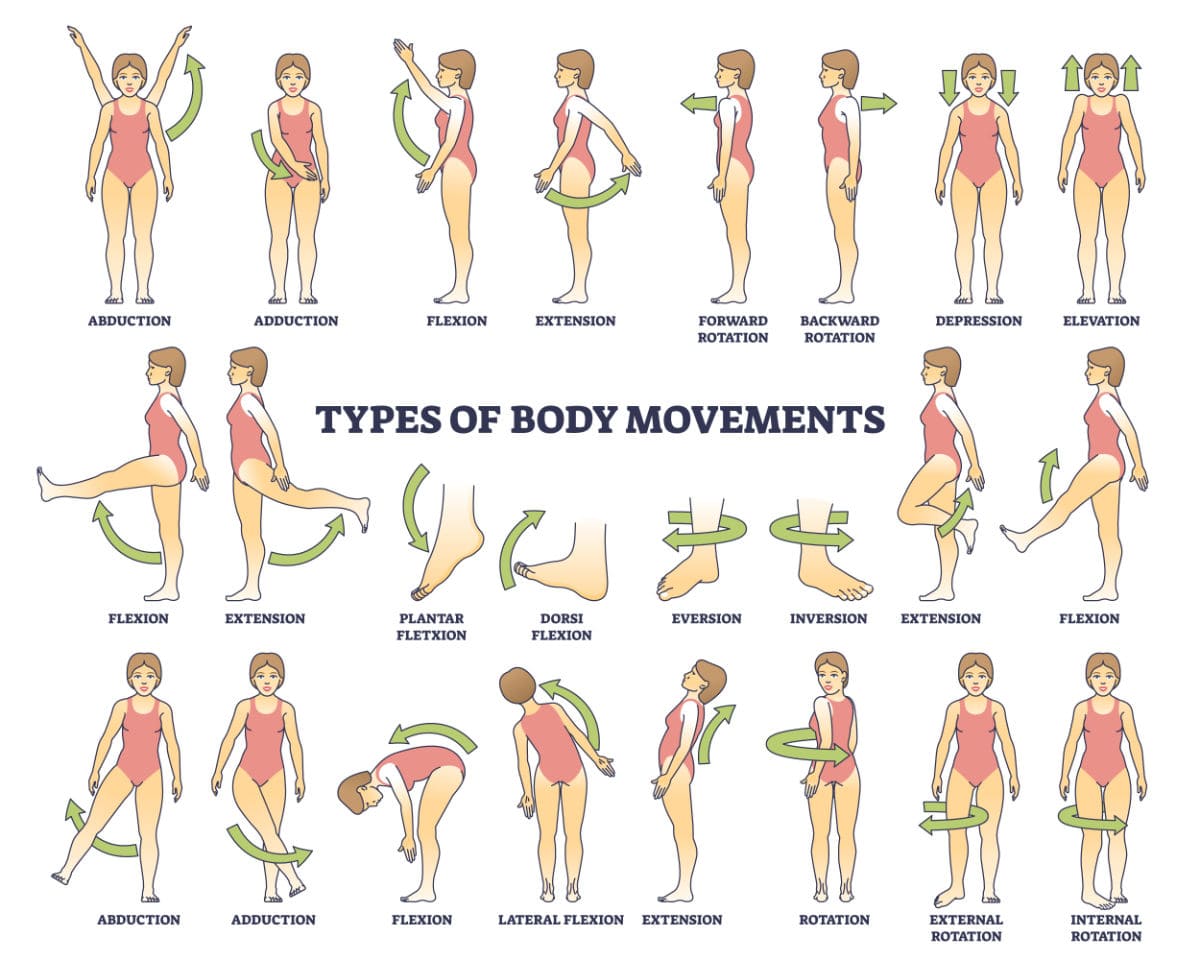

- Standard Anatomical Position: All descriptions of body regions, locations, and movements are made with reference to the standard anatomical position (standing erect, feet parallel, arms at sides, palms facing forward). This provides a universal baseline.

- Directional Terms:

- Superior (Cranial): Towards the head.

- Inferior (Caudal): Away from the head, towards the lower part of the body.

- Anterior (Ventral): Towards the front of the body.

- Posterior (Dorsal): Towards the back of the body.

- Medial: Towards the midline of the body.

- Lateral: Away from the midline of the body.

- Proximal: Closer to the point of origin or attachment (e.g., limb).

- Distal: Farther from the point of origin or attachment (e.g., limb).

- Superficial: Towards the body surface.

- Deep: Away from the body surface, internal.

- Ipsilateral: On the same side of the body.

- Contralateral: On the opposite side of the body.

- Regional Terms: Using the precise names for body regions (e.g., "brachial" for arm, "femoral" for thigh, "lumbar" for lower back) rather than colloquial terms ensures accuracy.

B. Specific Application to Abdominal Regions:

- Quadrant Terminology (for broad localization):

- "Patient complains of sharp pain in the Right Upper Quadrant (RUQ), radiating to the back."

- "A palpable mass was noted in the Left Lower Quadrant (LLQ)."

- "Bowel sounds are present and active in all four quadrants."

- Regional Terminology (for precise localization):

- "Tenderness elicited on deep palpation of the Right Iliac Region (McBurney's point)."

- "The patient reports a burning sensation localized to the Epigastric Region."

- "An enlarged spleen was palpated extending into the Left Hypochondriac and Left Lumbar Regions."

- "A hernia was identified in the Hypogastric Region, superior to the pubic symphysis."

- Combining Terms: Clinicians often combine regional terms with directional terms for even greater specificity.

- "Pain is superficial in the right lumbar region."

- "The lesion is located medial to the left midclavicular line within the umbilical region."

- Always use anatomical terms over vague descriptions. Instead of "stomach area," say "epigastric region" or "LUQ" depending on specificity required.

- When reporting findings, be consistent with the chosen system (quadrants or regions) and always reference the standard anatomical position implicitly.

Source: https://doctorsrevisionuganda.com | Whatsapp: 0726113908

Body Regions & Quadrants

Test your knowledge with these 20 questions.

Body Regions & Quadrants Quiz

Question 1/20

Quiz Complete!

Here are your results, .

Your Score

18/20

90%