Haemodynamics GFR & Diuretics

Functional Anatomy of the Kidneys

The urinary system is a vital organ system responsible for filtering blood, maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance, and excreting waste products.

Components of the Urinary System

- Paired Kidneys: These are the primary organs, responsible for blood filtration and urine formation.

- A Ureter for Each Kidney: Muscular tubes that transport urine from the kidneys to the urinary bladder.

- Urinary Bladder: An expandable muscular sac that stores urine until it's expelled from the body.

- Urethra: A tube that carries urine from the bladder to the outside of the body.

Main Functions of the Urinary System

- Blood Filtration and Waste Excretion:

- Filter blood: They continuously process blood, removing unwanted substances.

- Dispose of nitrogenous wastes: These are toxic byproducts of protein metabolism.

- Urea: The most abundant nitrogenous waste, formed from ammonia in the liver.

- Uric acid: A byproduct of nucleic acid metabolism.

- Creatinine: A waste product from muscle metabolism (creatine phosphate breakdown).

- Remove other toxins: Including drugs, environmental toxins, and various metabolic byproducts.

- Eliminate excess water and ions: Maintaining appropriate body fluid volume and electrolyte concentrations.

- Regulation of Homeostasis:

- Regulate the balance of water and electrolytes: Essential for maintaining cell volume, nerve impulse transmission, and muscle contraction.

- Regulate acid-base balance: By excreting hydrogen ions and reabsorbing bicarbonate ions, the kidneys play a crucial role in maintaining blood pH.

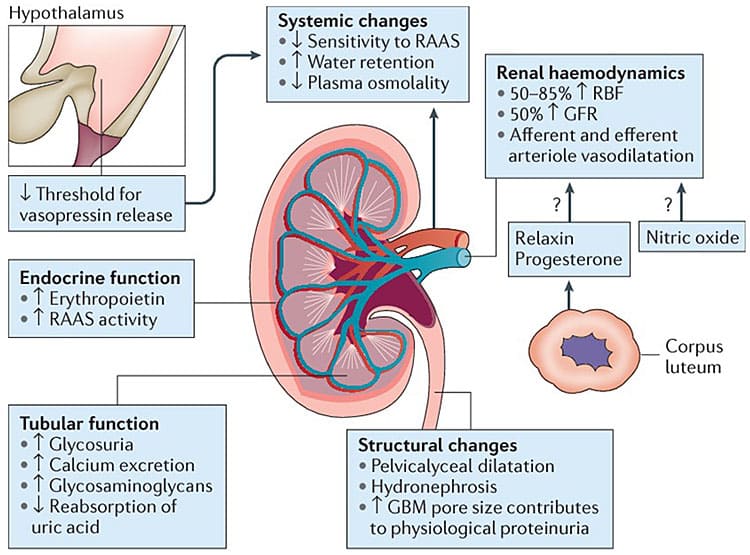

- Endocrine Functions (Hormone Production):

- Erythropoietin (EPO): Stimulates red blood cell production in the bone marrow in response to hypoxia.

- Renin: An enzyme that initiates the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS), which regulates blood pressure and fluid balance.

- Activation of Vitamin D: Converts inactive vitamin D into its active form (calcitriol), essential for calcium absorption and bone health.

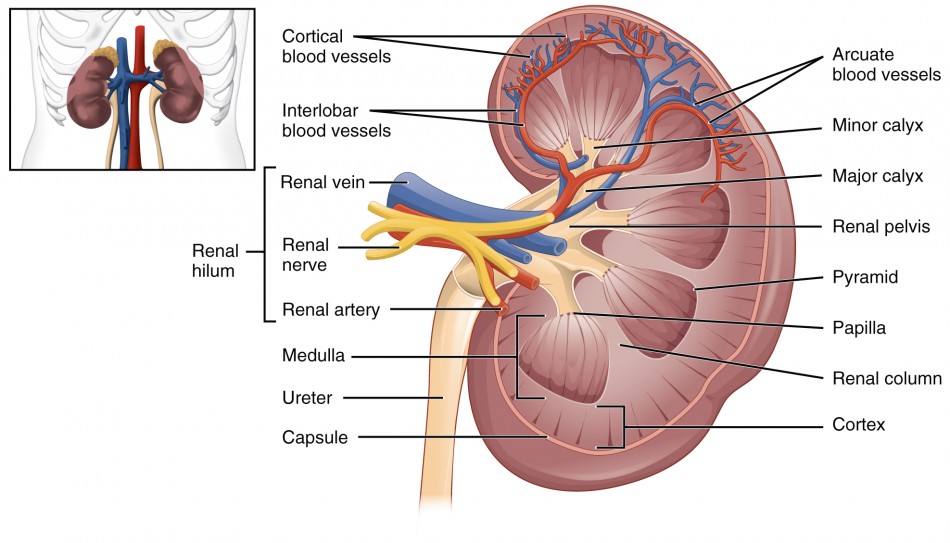

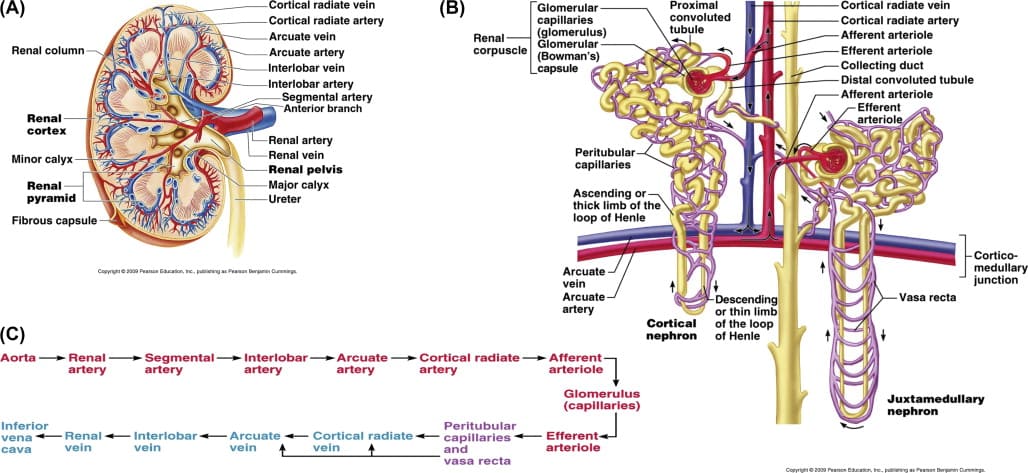

Gross Anatomy of the Kidneys

- Location:

- Retroperitoneal organs: This means they are located posterior to the parietal peritoneum, against the posterior abdominal wall. This is a key anatomical landmark.

- Superior lumbar region: Extending from the T12 to L3 vertebrae. The right kidney is often slightly lower than the left due to the presence of the liver.

- Shape and Orientation:

- Bean-shaped: With a characteristic convex lateral surface and a concave medial surface.

- Hilus (or Hilum): This is the prominent indentation on the medial surface. It serves as the entry and exit point for the renal artery, renal vein, nerves, and the ureter.

- Associated Structures:

- Adrenal glands (Suprarenal glands): These endocrine glands sit superior to each kidney, but are functionally separate from the kidneys.

Internal Anatomy of the Kidney: Macroscopic Structure

Upon dissection, the kidney reveals two main regions and further subdivisions:

- Renal Cortex (Outer Region): Lighter in color, granular texture.

- Renal Columns: Extensions of the cortex that project down into the medulla, dividing it into distinct pyramid-shaped sections. These columns contain blood vessels and parts of the nephrons.

- Renal Medulla (Inner Region): Darker, cone-shaped structures.

- Renal Pyramids (Medullary Pyramids): 8-18 cone-shaped masses, with their bases facing the cortex and their apices (renal papillae) pointing towards the renal pelvis. These contain parallel bundles of urine-collecting tubules and loops of Henle.

- Renal Papilla: The apex of each renal pyramid, from which urine drains into a minor calyx.

- Renal Lobe: Consists of a renal pyramid and the cortical tissue surrounding it (the renal column on either side and the cortical tissue overlying its base).

- Number: 5-11 lobes per kidney. Each lobe functions somewhat independently in urine production.

- Collecting System:

- Minor Calyx (plural: Calices): Cup-shaped structures that collect urine directly from the renal papillae of individual pyramids.

- Major Calyx: Two or three minor calices merge to form a major calyx.

- Renal Pelvis: The expanded, funnel-shaped superior part of the ureter. It is formed by the convergence of the major calices and acts as a reservoir for urine before it enters the ureter.

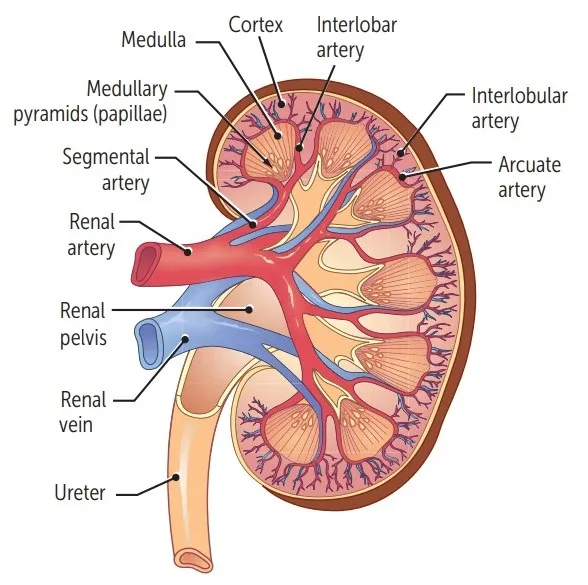

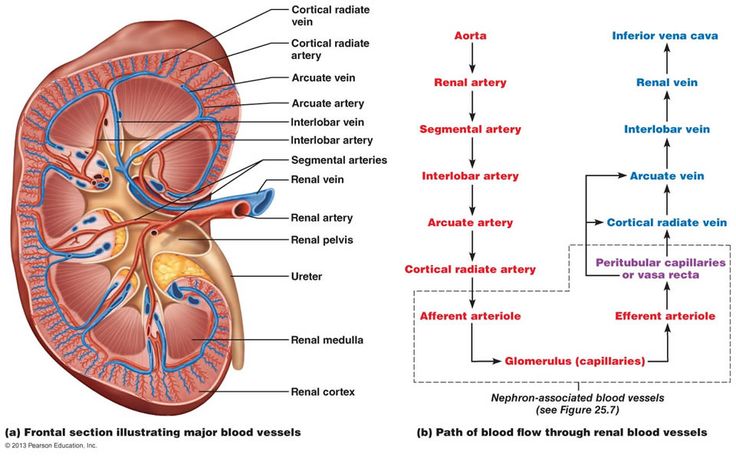

Blood Supply to the Kidneys

The kidneys receive a disproportionately large blood supply (about 20-25% of cardiac output) due to their role in blood filtration. Cortex receives >90%.

- Aorta: The abdominal aorta gives rise to the right and left renal arteries.

- Renal Artery: Enters the kidney at the hilus.

- Segmental Arteries: Within the hilus, the renal artery typically divides into 5 segmental arteries.

- Interlobar Arteries: Segmental arteries branch into interlobar arteries, which pass through the renal columns between the renal pyramids, extending towards the cortex.

- Arcuate Arteries: At the junction of the medulla and cortex (the corticomedullary junction), the interlobar arteries arch over the bases of the pyramids to become arcuate arteries.

- Cortical Radiate Arteries (Interlobular Arteries): Arcuate arteries give off numerous cortical radiate arteries that project into the cortex.

- Afferent Arterioles: Each cortical radiate artery gives rise to numerous afferent arterioles, which supply blood to individual glomeruli.

The Unique Renal Vasculature

Glomerular Capillary Bed

- Afferent Arteriole: Carries blood to the glomerulus. Larger in diameter, bringing blood to the glomerulus.

- Efferent Arteriole: Carries blood away from the glomerulus. Smaller in diameter, carrying blood away from the glomerulus. This is distinct from most capillary beds, which drain into venules.

SIGNIFICANCE: The difference in diameter between the afferent and efferent arterioles creates resistance to blood flow, maintaining the high hydrostatic pressure within the glomerulus. This high pressure is the primary driving force for glomerular filtration, literally "forcing" filtrate out of the blood.

Two Capillary Beds in Series

This is a defining feature of the renal circulation:

- Glomerulus: The first capillary bed, specialized for filtration.

- Peritubular Capillaries (or Vasa Recta): The second capillary bed, arising from the efferent arteriole, specialized for reabsorption and secretion.

A. Peritubular Capillaries

- Origin: Arise from the efferent arterioles.

- Location: Primarily surround the PCT and DCT in the renal cortex.

- Structure: Low-pressure, porous capillaries.

- Function: Specialized for reabsorption, readily taking up water, solutes, and nutrients that are reabsorbed by the tubule cells. They also play a role in secretion.

B. Vasa Recta

Specific Portion of Peritubular Capillary System. Long, straight capillaries that extend deep into the medulla, running parallel to the loops of Henle of juxtamedullary nephrons. They are crucial for maintaining the medullary osmotic gradient.

Function: The Vasa Recta acts as a countercurrent exchanger

- Problem: The high solute concentration (hyperosmolarity) in the medullary interstitium, created by the loop of Henle, is essential for concentrating urine. If regular capillaries simply flowed through, they would rapidly "wash out" this gradient.

- Solution: The countercurrent flow within the vasa recta minimizes the loss of solutes from the medullary interstitium. As blood flows down into the hyperosmotic medulla, it picks up solutes and loses water. As it flows back up out of the medulla, it loses solutes and picks up water. This exchange maintains the osmotic gradient.

- Result: The vasa recta are able to supply nutrients and remove water from the medulla without dissipating the crucial medullary osmotic gradient.

Role with Loop of Henle: The loop of Henle is the "countercurrent multiplier" (creating the gradient), while the vasa recta is the "countercurrent exchanger" (preserving the gradient).

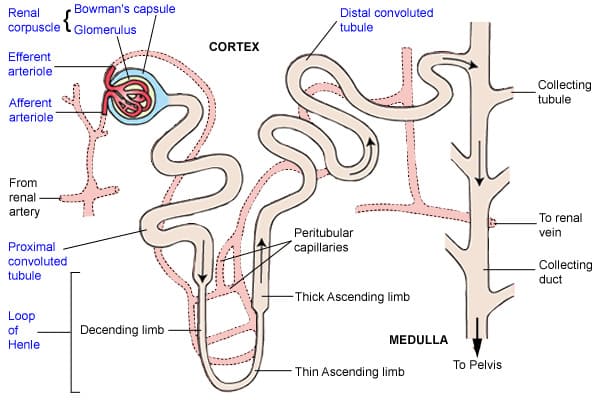

The Uriniferous Tubule (Renal Tubule) - The Functional Unit

This is the main structural and functional unit of the kidney! It's better known as the nephron. The nephron is the microscopic functional unit of the kidney, responsible for forming urine. There are over a million nephrons in each kidney.

Two Major Parts:

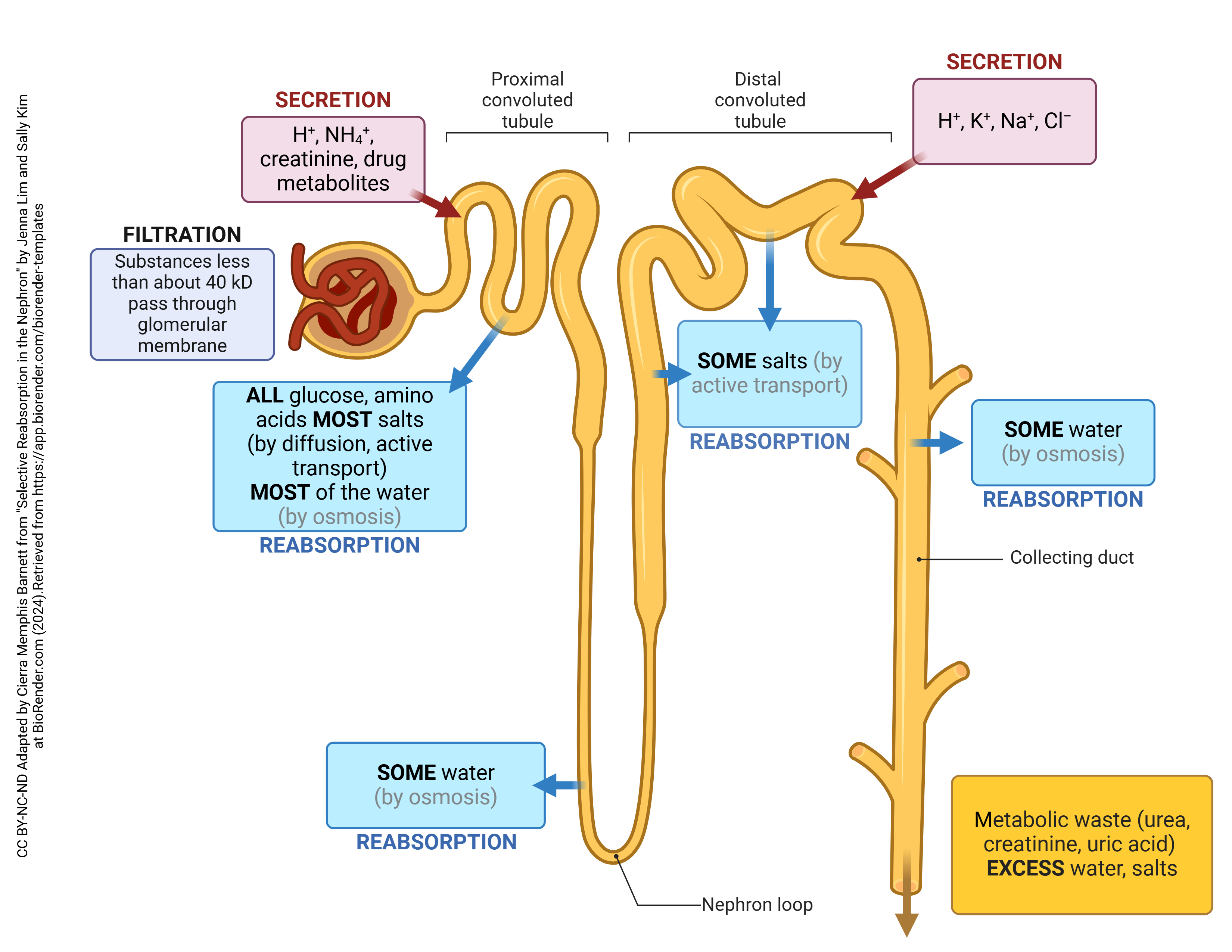

- Renal Corpuscle (The urine-forming nephron part): Consists of the glomerulus and Bowman's capsule. This is where filtration occurs.

- Renal Tubule: This is where the filtrate is processed (reabsorption and secretion).

- Glomerular Filtration: The bulk movement of fluid and small solutes from the blood in the glomerulus into Bowman's capsule, forming the "filtrate."

- Tubular Reabsorption: The selective return of useful substances (water, electrolytes, nutrients) from the filtrate back into the blood in the peritubular capillaries.

- Tubular Secretion: The selective movement of additional waste products, excess ions, and toxins from the blood in the peritubular capillaries into the filtrate within the renal tubule, for excretion in urine.

The Nephron

The nephron is indeed the microscopic workhorse of the kidney, responsible for the actual filtration of blood and the formation of urine. Each kidney contains over a million nephrons. A nephron consists of two main parts: the renal corpuscle and the renal tubule.

1. Renal Corpuscle

- Location: Always found exclusively in the renal cortex.

- Components:

- Glomerulus: This is a specialized tuft of fenestrated capillaries. It's unique because it's situated between two arterioles (afferent and efferent), which helps maintain the high pressure necessary for filtration. The primary function of the glomerulus is filtration of blood plasma.

- Bowman's Capsule:

- Parietal layer: The outer layer, made of simple squamous epithelium.

- Visceral layer: The inner layer, which intimately covers the glomerular capillaries. This layer is composed of specialized cells called podocytes. Podocytes have foot-like processes (pedicels) that interdigitate to form filtration slits, which are crucial components of the filtration barrier.

- Function: Together, the glomerulus and Bowman's capsule form the filtration membrane (or barrier), allowing the passage of water and small solutes from the blood into Bowman's space, while retaining blood cells and large proteins. The fluid collected in Bowman's space is called glomerular filtrate.

- Classes include: cortical and Juxtamedullary nephrons

2. Renal Tubule

This is a long, convoluted tubule that extends from Bowman's capsule and processes the glomerular filtrate through reabsorption and secretion.

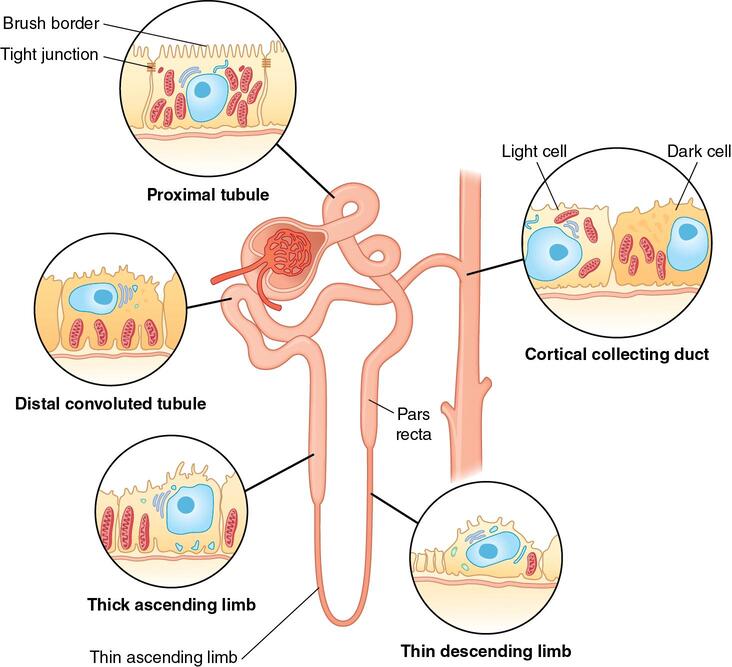

Proximal Convoluted Tubule (PCT):

- Location: Lies entirely within the renal cortex.

- Structure: Highly convoluted (twisted) with a lining of cuboidal epithelial cells featuring abundant microvilli (forming a "brush border") on their apical surface, and numerous mitochondria.

- Function: This is the primary site of non-regulated reabsorption. About 65-70% of filtered water, Na+, Cl-, HCO3-, and nearly all filtered glucose and amino acids are reabsorbed here. It also secretes some organic acids and bases. The brush border significantly increases surface area for reabsorption.

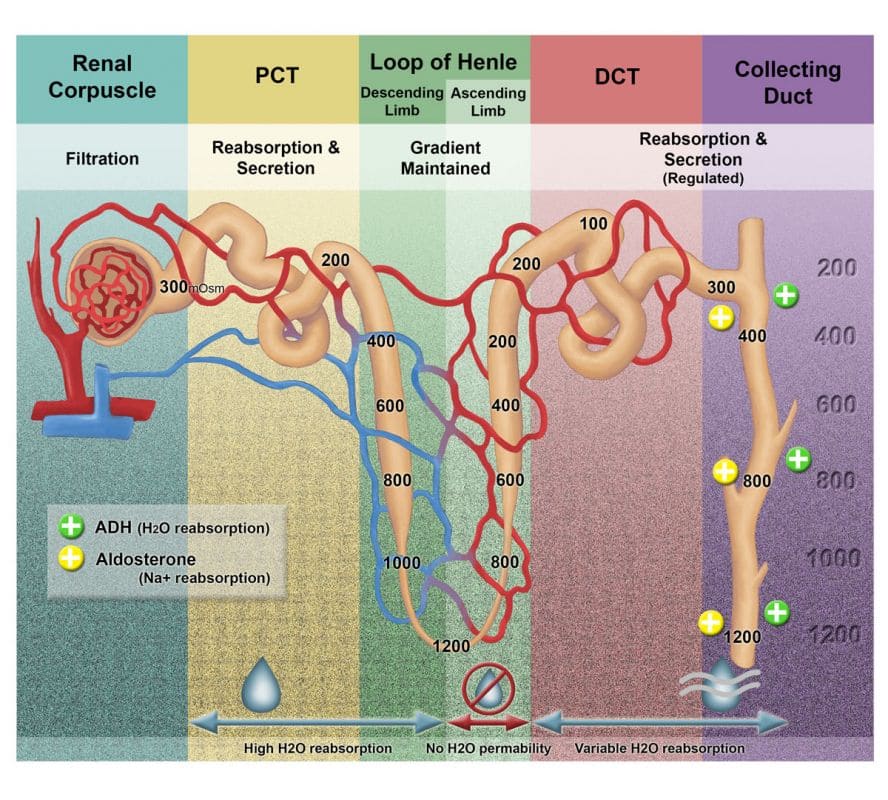

Loop of Henle (Nephron Loop):

- Structure: A hairpin-shaped loop that dips down into the renal medulla (the extent depends on the type of nephron). It has two limbs:

- Descending Limb: Permeable to water but impermeable to solutes.

- Ascending Limb: Impermeable to water but actively transports (reabsorbs) solutes (Na+, Cl-, K+). It has a thin segment (passive transport) and a thick segment (active transport).

- Function: Creates and maintains the medullary osmotic gradient through its countercurrent multiplier mechanism. This gradient is essential for the kidney's ability to produce concentrated urine.

Distal Convoluted Tubule (DCT):

- Location: Lies entirely within the renal cortex.

- Structure: Less convoluted than the PCT, also lined with cuboidal epithelial cells, but with fewer microvilli and mitochondria compared to the PCT.

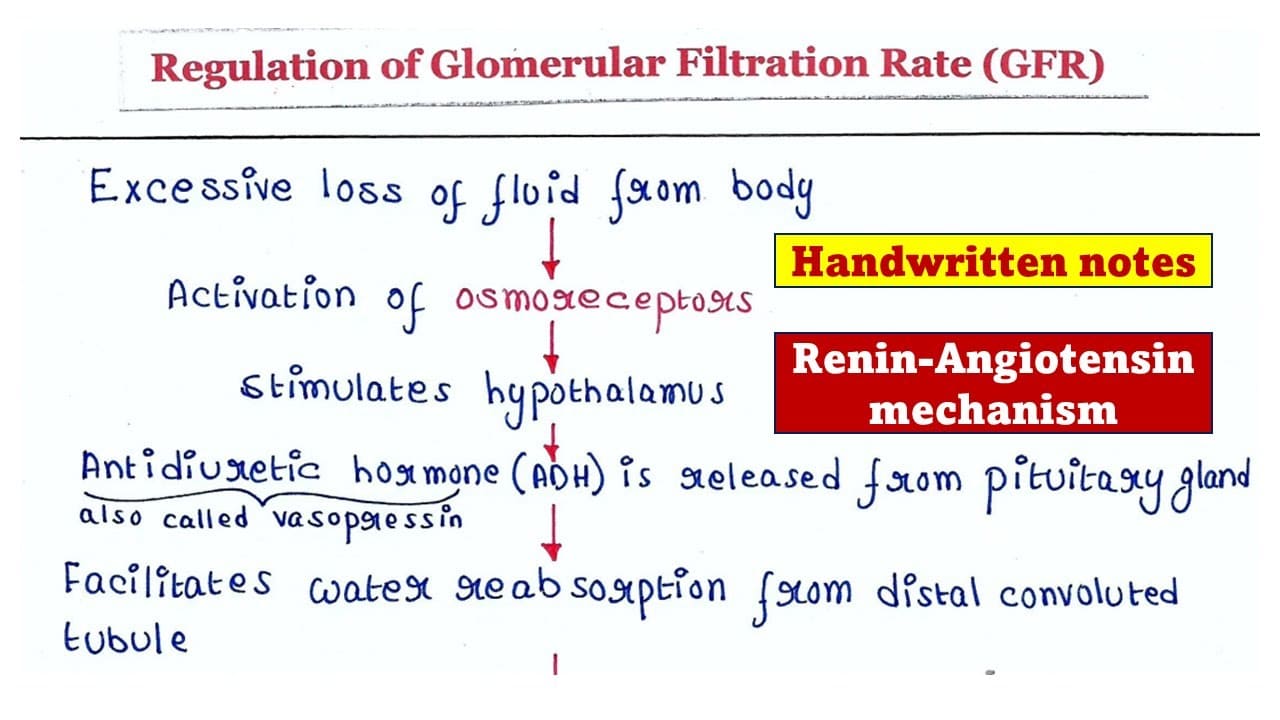

- Function: This is the primary site of regulated reabsorption and secretion. Hormones like aldosterone and antidiuretic hormone (ADH) act here to fine-tune the reabsorption of Na+, Cl-, and water, and the secretion of K+ and H+. It plays a critical role in maintaining electrolyte and acid-base balance.

The Collecting Ducts

- Structure: Collecting ducts receive filtrate from multiple nephrons. They begin in the cortex and extend deep into the renal medulla, converging to form larger papillary ducts that eventually drain urine into the minor calyces.

- Cell Types: Primarily composed of:

- Principal cells: Responsible for Na+ and water reabsorption, and K+ secretion, mainly under hormonal control (aldosterone and ADH).

- Intercalated cells: Play a role in acid-base balance by secreting H+ or HCO3-.

- Most Important Role: Water Conservation (under ADH control):

- When the body must conserve water: The posterior pituitary gland secretes Antidiuretic Hormone (ADH), also known as vasopressin.

- ADH Action: ADH increases the permeability of the principal cells in the collecting tubules and the late distal tubules to water by inserting aquaporin-2 water channels into their apical membranes.

- Result: This allows more water to be reabsorbed from the filtrate, moving down its osmotic gradient into the hyperosmotic renal medulla.

- Effect on Urine: This significantly decreases the total volume of urine and makes it more concentrated.

Determinants of Renal Blood Flow (RBF)

Renal blood flow (RBF) is the volume of blood flowing through the kidneys per unit of time. It directly impacts the glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

Formula: The flow rate through any organ is determined by the pressure difference across the vascular bed and the total vascular resistance.

RBF = (Renal Artery Pressure - Renal Vein Pressure) / Total Renal Vascular Resistance

- Pressure Gradient:

- Renal Artery Pressure: Close to systemic arterial pressure (e.g., 90-100 mmHg mean arterial pressure).

- Renal Vein Pressure: Is significantly lower, around 3-4 mmHg.

- This large pressure gradient provides a strong driving force for blood flow through the kidneys.

- Total Renal Vascular Resistance: Resistance to blood flow within the kidney primarily occurs in the small arteries and arterioles, particularly the interlobar arteries, arcuate arteries, cortical radiate arteries, afferent arterioles, and efferent arterioles.

- Control Mechanisms: This resistance is tightly regulated by:

- Sympathetic Nervous System: Norepinephrine released by sympathetic nerves causes vasoconstriction, primarily of the afferent arterioles, reducing RBF and GFR.

- Hormones: Various circulating hormones, such as angiotensin II (vasoconstriction) and prostaglandins (vasodilation), also influence renal vascular resistance.

- Local Internal Renal Control Mechanisms (Autoregulation): These intrinsic mechanisms are particularly important for maintaining stable RBF and GFR, as detailed below.

- Impact: An increase in vascular resistance will decrease RBF (and often GFR), and vice versa.

- Control Mechanisms: This resistance is tightly regulated by:

- Oxygen Consumption: On a per gram weight basis, kidneys usually consume oxygen at twice the rate of the brain but have almost 7 times the blood flow to the brain. If renal blood flow & GFR reduce, less Na+ is filtered & reabsorbed hence consuming less oxygen. Renal O2 consumption is directly related to Na+ re-absorption.

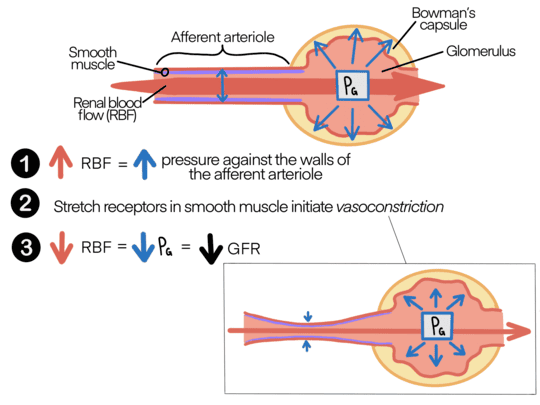

Renal Autoregulation of RBF and GFR

The kidneys possess powerful intrinsic mechanisms to maintain RBF and GFR relatively constant, despite significant fluctuations in systemic arterial blood pressure. This autoregulation works effectively over a wide range of mean arterial pressures, between 80-170 mmHg. This protects the delicate glomerular capillaries from damage due to high pressure and ensures a stable filtration rate for precise waste removal and fluid balance.

There are two primary mechanisms involved in renal autoregulation:

1. Myogenic Response

This is an intrinsic property of the smooth muscle in the walls of the afferent arterioles.

Increased Blood Pressure (and RBF):

- An increase in systemic blood pressure stretches the smooth muscle cells in the wall of the afferent arteriole.

- This stretching opens mechanosensitive ion channels (specifically voltage-gated calcium channels) in the smooth muscle cell membrane.

- Influx of Calcium Ions (Ca2+): The influx of Ca2+ from the extracellular fluid (ECF) into the smooth muscle cells causes them to contract.

- Vasoconstriction: This leads to constriction of the afferent arteriole, which increases its resistance.

- Result: The increased resistance counteracts the increased blood pressure, thereby maintaining RBF and GFR at a relatively constant level.

Decreased Blood Pressure (and RBF):

- A decrease in systemic blood pressure reduces the stretch on the afferent arteriole.

- This reduces Ca2+ influx, leading to relaxation of the smooth muscle.

- Vasodilation: The afferent arteriole dilates, decreasing its resistance.

- Result: This helps to restore RBF and GFR towards normal levels.

2. Tubuloglomerular Feedback (TGF)

This involves communication between the renal tubule and the afferent arteriole, mediated by the juxtaglomerular apparatus (JGA).

Macula Densa: These are specialized chemoreceptor cells located in the wall of the distal convoluted tubule (specifically, the initial part) where it passes adjacent to the afferent and efferent arterioles of its own glomerulus. They are sensitive to the concentration of NaCl in the tubular fluid.

Sequence of Events for Increased GFR:

- Increase in GFR: Leads to a faster flow rate of filtrate through the renal tubule.

- Increased NaCl Concentration: Due to the faster flow, there is less time for NaCl to be reabsorbed in the PCT and Loop of Henle, resulting in an increase in NaCl concentration reaching the macula densa cells.

- Macula Densa Response: The macula densa cells detect this increased NaCl. They release vasoconstrictor substances (e.g., adenosine from ATP breakdown) into the interstitial fluid surrounding the afferent arteriole.

- Constriction of Afferent Arteriole: Adenosine causes vasoconstriction of the afferent arteriole.

- Decrease in GFR: The increased resistance in the afferent arteriole reduces glomerular blood flow and subsequently decreases GFR back towards normal.

Sequence of Events for Decreased GFR:

- Decrease in GFR: Leads to a slower flow rate of filtrate.

- Decreased NaCl Concentration: More time for NaCl reabsorption results in a decrease in NaCl concentration reaching the macula densa.

- Macula Densa Response: The macula densa cells respond by releasing vasodilator substances (e.g., prostaglandins, nitric oxide) and decreasing the release of vasoconstrictors. Critically, a decrease in NaCl delivery to the macula densa also stimulates the release of renin from the juxtaglomerular (granular) cells of the afferent arteriole. Renin leads to the production of angiotensin II, which can cause both afferent and efferent arteriolar constriction, but in this context, the local vasodilatory signals often dominate the afferent arteriole.

- Dilation of Afferent Arteriole: The vasodilatory substances cause dilation of the afferent arteriole.

- Increase in GFR: The decreased resistance in the afferent arteriole increases glomerular blood flow and hence increases GFR back towards normal.

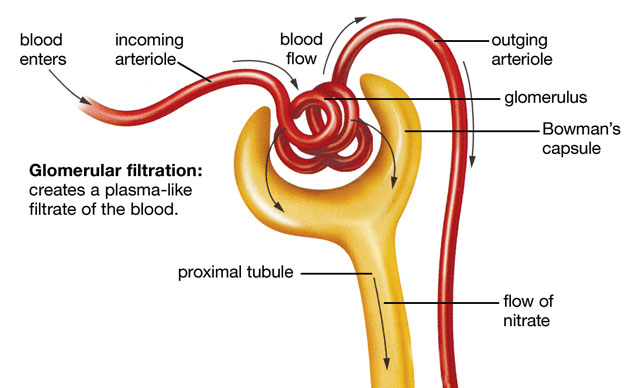

Glomerular Filtration

Glomerular filtration is the initial, non-selective step in urine formation. It involves the bulk movement of fluid and small solutes from the blood in the glomerular capillaries into Bowman's capsule.

- Process: Blood flows through the glomerulus, and a protein-free plasma ultrafiltrate is forced through the specialized filtration barrier into Bowman's space.

- Fraction Filtered: Approximately 20% of the plasma entering the glomerulus is filtered. This is known as the filtration fraction.

Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR)

The volume of plasma filtrate produced by both kidneys per minute.

- Average Rate:

- Per minute: 125 ml/min (which is about 16-20% of the renal plasma flow, ~650 ml/min * 0.19 = 123.5 ml/min).

- Per day: 180 L/day.

- Reabsorption: About 99% of this filtered fluid (178.5 L/day) is reabsorbed back into the blood. Only 1% (1.5 – 2 L/day) is excreted as urine.

- Consequence of Impaired Reabsorption: If this reabsorption did not occur, death from dehydration would ensue rapidly.

- Variability: GFR can vary with factors like kidney size, lean body weight, and the number of functional nephrons.

Factors Determining Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR)

GFR is determined by four main factors:

1. Net Filtration Pressure (NFP) - The Starling Forces

Starling forces are the hydrostatic and oncotic (colloid osmotic) pressure gradients acting across a capillary membrane. In the glomerulus, these forces determine the net pressure driving fluid out of the capillaries and into Bowman's capsule.

Formula: NFP = (Pgl - Pbs) - (πgl - πbs)

Where:

- Pgl: Glomerular hydrostatic pressure (promotes filtration)

- Pbs: Hydrostatic pressure in Bowman's capsule (opposes filtration)

- πgl: Colloid osmotic pressure of glomerular plasma proteins (opposes filtration)

- πbs: Colloid osmotic pressure in Bowman's capsule (usually negligible, close to 0, as healthy glomeruli prevent protein passage).

Typical Values:

A. Glomerular Hydrostatic Pressure (Pgl): ~ 60 mmHg

This is the main force promoting filtration.

- Increases Pgl (and thus GFR): Moderate increase in arterial blood pressure (though often buffered by autoregulation).

- Afferent arteriole vasodilation: Increases blood flow into the glomerulus.

- Moderate efferent arteriole vasoconstriction: "Backs up" blood in the glomerulus, raising pressure.

- Decreases Pgl (and thus GFR):

- Afferent arteriole vasoconstriction: Reduces blood flow into the glomerulus.

- Efferent arteriole vasodilation: Reduces resistance, allowing blood to flow out of the glomerulus more easily, dropping pressure.

B. Hydrostatic Pressure in Bowman's Capsule (Pbs): ~ 18 mmHg

This force opposes filtration.

- Increases Pbs (and thus decreases GFR):

- Urinary obstruction: Any blockage downstream from Bowman's capsule (e.g., kidney stones, enlarged prostate) causes urine to back up, increasing pressure in the capsule.

- Kidney edema: Swelling of the kidney tissue can compress Bowman's capsule, raising pressure.

C. Colloid Osmotic Pressure of Glomerular Plasma Proteins (πgl): ~ 32 mmHg

This force opposes filtration because the proteins in the blood "pull" water back into the capillaries.

- Increases πgl (and thus decreases GFR):

- Dehydration: Increases the concentration of plasma proteins.

- Decrease in renal blood flow: If RBF slows, more water is filtered, concentrating the proteins in the remaining blood in the glomerulus.

- Severe efferent vasoconstriction: While initially increasing Pgl, if severe enough, it significantly slows flow, allowing more filtration and thus a higher concentration of proteins in the remaining glomerular blood, which can ultimately decrease NFP and GFR (as you correctly noted, this is a pathological condition).

- Decreases πgl (and thus increases GFR):

- Hypoproteinemia: Low plasma protein levels (e.g., due to liver disease, malnutrition, or protein loss syndromes).

- Increase in renal blood flow: Less time for plasma proteins to become concentrated.

Calculated NFP: Using the typical values, NFP = 60 - 18 - 32 = 10 mmHg. This small net driving pressure underscores the efficiency and delicate balance of glomerular filtration.

2. Blood Circulation Throughout the Kidneys (Renal Blood Flow & Renal Plasma Flow)

The volume of blood delivered to the glomeruli directly influences the amount of plasma available for filtration and the pressures within the glomerulus.

- Renal Blood Flow (RBF): Approximately 1200 ml/min (~20% of cardiac output).

- Renal Plasma Flow (RPF): Approximately 650 ml/min (RBF * (1 - hematocrit)).

3. Permeability of the Filtration Barrier

The glomerular filtration barrier is a highly specialized, three-layered structure that allows the passage of water and small solutes but restricts larger molecules (like proteins) and cells.

- A. The Fenestrated Endothelium of the Glomerular Capillary: The innermost layer. Endothelial cells have numerous large pores (fenestrations) that make them highly permeable. They prevent the filtration of blood cells.

- B. The Glomerular Basement Membrane (GBM): A fused, non-cellular layer composed of glycoproteins and proteoglycans. It is highly negatively charged due to the presence of proteoglycans. This negative charge is crucial for repelling negatively charged plasma proteins (like albumin), thus preventing their filtration.

- C. The Filtration Slits formed by Podocytes: The outermost layer. Podocytes are specialized epithelial cells of the visceral layer of Bowman's capsule. Their foot processes (pedicels) interdigitate to form narrow gaps called filtration slits, which are bridged by slit diaphragms. These diaphragms act as a final selective barrier, preventing the passage of most proteins.

4. Filtration Membrane Surface Area

The total surface area available for filtration directly impacts GFR.

- Factors influencing surface area:

- Mesangial cells: These specialized cells within the glomerulus can contract, altering the surface area of the glomerular capillaries available for filtration.

- Disease states: Glomerular diseases (e.g., glomerulonephritis) can reduce the number of functional glomeruli or damage the filtration barrier, decreasing surface area and permeability.

- Relationship between GFR and NFP:

- ↑ NFP → ↑ GFR

- ↓ NFP → ↓ GFR

If GFR is too high:

- Fluid flows through the renal tubules too rapidly.

- There is insufficient time for adequate reabsorption of essential substances (water, electrolytes, nutrients).

- This leads to excessive urine output, posing a threat of dehydration and electrolyte depletion.

- Fluid flows sluggishly through the tubules.

- Tubules reabsorb waste products (like urea, creatinine, uric acid) that should be eliminated from the body.

- This leads to the accumulation of nitrogen-containing substances in the blood, a condition known as azotemia, which can progress to uremia and cause severe systemic effects.

Regulation of Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR)

Maintaining a stable GFR is paramount for overall body homeostasis. It's too high, and valuable substances are lost; it's too low, and wastes accumulate. GFR is primarily controlled by adjusting glomerular blood pressure (Pgc) and, to a lesser extent, the filtration coefficient (Kf) (which relates to permeability and surface area of the filtration barrier).

1. Autoregulation (Intrinsic Mechanisms)

These mechanisms operate within the kidney to maintain GFR relatively constant despite changes in systemic arterial pressure (between 80-170 mmHg).

- A. Myogenic Mechanism: covered

- B. Tubuloglomerular Feedback (TGF): covered

2. Sympathetic Control (Extrinsic Mechanism)

When the body is under significant stress, the sympathetic nervous system can override renal autoregulation.

- At Rest: Renal blood vessels are maximally dilated (or only moderately constricted), and autoregulation mechanisms prevail.

- Under Stress (e.g., severe hemorrhage, "fight-or-flight" situations):

- Norepinephrine is released from sympathetic nerve endings, and epinephrine is released from the adrenal medulla.

- These catecholamines act on alpha-1 adrenergic receptors on both afferent and efferent arterioles, causing vasoconstriction. The afferent arteriole is generally more sensitive and constricts more significantly.

- Result: Significant afferent arteriole vasoconstriction, which drastically reduces renal blood flow and decreases GFR.

- Physiological Purpose: This shunts blood away from the kidneys and towards more vital organs (brain, heart, skeletal muscle) during acute crises.

- Additional Effect: Sympathetic stimulation also directly stimulates the juxtaglomerular cells to release renin, activating the renin-angiotensin system, which further contributes to vasoconstriction (especially efferent) and helps maintain systemic blood pressure.

3. Hormonal Control

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS):

- Stimuli for Renin Release:

- Decreased NaCl delivery to the macula densa (as in TGF).

- Decreased renal perfusion pressure (detected by baroreceptors in the afferent arteriole).

- Sympathetic nerve stimulation (beta-1 receptors on JG cells).

- Angiotensin II:

- A potent vasoconstrictor, especially of the efferent arteriole. Efferent constriction increases Pgc and thus GFR (up to a point).

- Also causes systemic vasoconstriction, helping to raise overall blood pressure.

- Stimulates aldosterone release (Na+ reabsorption) and ADH release (water reabsorption).

Prostaglandins:

Renal prostaglandins (e.g., PGE2, PGI2) are local vasodilators. They counteract the vasoconstrictive effects of sympathetic activity and angiotensin II, helping to maintain GFR when renal perfusion is threatened. NSAIDs (like ibuprofen) can inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, which can decrease GFR, especially in compromised kidneys.

Natriuretic Peptides (ANP, BNP):

Released in response to high blood volume/pressure. They cause vasodilation (especially of the afferent arteriole) and inhibit renin/aldosterone, generally increasing GFR and promoting Na+/water excretion.

Clinical Application of RAAS Inhibitors (ACEIs and ARBs)

- ACE Inhibitors (ACEIs): Block the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II.

- Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs): Block the binding of angiotensin II to its receptors.

Effect on GFR: Both reduce the effects of angiotensin II, including its efferent arteriolar vasoconstriction.

Consequence: Loss of efferent arteriolar vasoconstriction leads to efferent vasodilation. This reduces Pgc and, therefore, decreases GFR.

Relevance in Renal Artery Stenosis:

- In renal artery stenosis, the kidney with the narrowed artery relies heavily on efferent arteriole constriction (mediated by locally high angiotensin II due to reduced perfusion) to maintain GFR.

- Administering ACEIs or ARBs in such patients blocks this compensatory efferent constriction, causing a precipitous drop in GFR and potentially leading to acute renal failure. This is why these drugs are contraindicated or used with extreme caution in bilateral renal artery stenosis (or unilateral stenosis in a patient with only one functional kidney).

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF RENAL TUBULAR TRANSPORT

All movement of substances across the renal tubule cells and into or out of the tubular lumen relies on fundamental transport mechanisms.

Transport Mechanisms Across Cell Membranes

These are the universal ways substances move across biological membranes:

Passive Transport

Movement of substances down their electrochemical gradient, requiring no direct energy expenditure by the cell.

- i. Diffusion: Random movement of molecules from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration. Examples in the kidney include the diffusion of urea.

- ii. Facilitated Diffusion: Movement of molecules down their electrochemical gradient, but requiring the assistance of a membrane protein (channel or carrier). Still passive, as no ATP is directly consumed.

- Channels: Provide a hydrophilic pore through which specific ions or water can pass (e.g., aquaporin channels for water, ion channels for K+).

- Carriers (Transporters): Bind to the solute and undergo a conformational change to move it across the membrane.

- Uniport: Transports a single solute in one direction (e.g., glucose transporters on the basolateral membrane of PCT cells).

- Coupled Transport (Cotransport): Transports two or more solutes simultaneously.

- Symport: Transports two or more solutes in the same direction (e.g., Na+-glucose cotransporter on the apical membrane of PCT cells).

- Antiport: Transports two or more solutes in opposite directions (e.g., Na+-H+ exchanger on the apical membrane of PCT cells).

- iii. Solvent Drag: Occurs when water moves across an epithelium by osmosis, carrying dissolved solutes with it (dragging them along). This is a passive process, and its importance is particularly noted in the paracellular pathway (between cells). For example, as water is reabsorbed in the proximal tubule, it can "drag" along solutes like Ca2+ and K+.

Active Transport

Movement of substances against their electrochemical gradient, requiring direct (primary active transport) or indirect (secondary active transport) energy expenditure by the cell (ATP hydrolysis).

- Primary Active Transport: Directly uses ATP (e.g., Na+-K+-ATPase pump on the basolateral membrane of all tubular cells, actively pumping Na+ out of the cell and K+ into the cell, creating gradients).

- Secondary Active Transport: Uses the electrochemical gradient established by primary active transport (e.g., the Na+ gradient created by the Na+-K+-ATPase) to move another substance against its gradient. Na+-glucose symporter is a classic example.

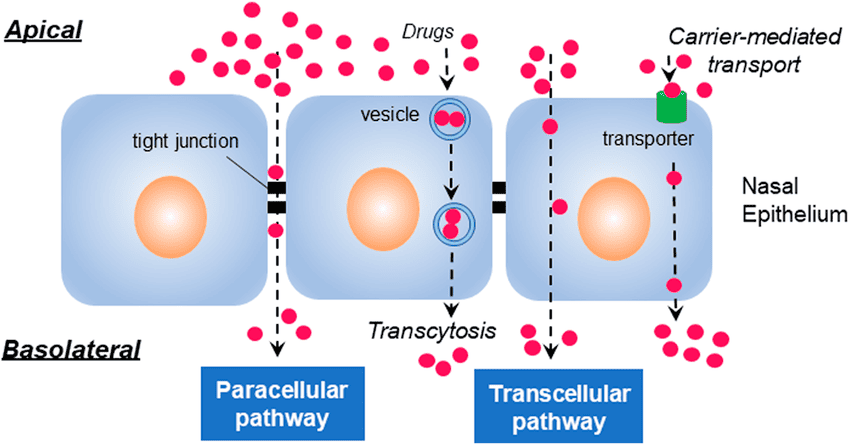

I. Transepithelial Transport Pathways (Routes of Reabsorption/Secretion)

Substances moving between the tubular lumen and the peritubular capillary must cross the renal tubular epithelium. There are two main routes:

A. Transcellular Pathway ("Through Cells"):

Substances move through the tubular epithelial cells, crossing two cell membranes:

- The apical (luminal) membrane: Facing the tubular fluid.

- The basolateral membrane: Facing the interstitial fluid and peritubular capillaries.

- Mechanism: This pathway involves a combination of channels, carriers, and pumps on both membranes.

- Example: Na+ Reabsorption in the Proximal Tubule (PT):

- Movement into the cell across the apical membrane: Na+ enters the cell from the tubular lumen, usually down its electrochemical gradient (due to low intracellular Na+ and negative cell potential). This can occur via channels, symporters (e.g., Na+-glucose), or antiporters (e.g., Na+-H+ exchanger).

- Movement into the extracellular fluid across the basolateral membrane: Na+ is actively pumped out of the cell into the interstitial fluid (against its electrochemical gradient) by the Na+-K+-ATPase pump. This pump is the primary engine driving most renal reabsorption, as it maintains the low intracellular Na+ concentration.

B. Paracellular Pathway ("Between Cells"):

Substances move between the tubular epithelial cells, passing through the tight junctions and the lateral intercellular spaces.

- Permeability: The "tightness" of these junctions varies along the nephron. The proximal tubule has relatively "leaky" tight junctions, allowing for significant paracellular transport. More distal segments have "tighter" junctions.

- Mechanisms: Primarily passive processes:

- Diffusion: Driven by concentration gradients.

- Solvent Drag: As water moves paracellularly due to osmotic gradients, it carries dissolved solutes with it.

- Examples:

- Reabsorption of Ca2+ and K+ across the PT: A significant portion of these ions can be reabsorbed paracellularly, especially in the proximal tubule.

- Water Reabsorption across the PT: While water also moves transcellularly via aquaporins, a considerable amount (especially in the proximal tubule) moves paracellularly.

- Solutes dissolved in water by solvent drag: As water is reabsorbed paracellularly, it drags along ions like Ca2+ and K+.

Tubular Reabsorption

The process of moving substances from the tubular lumen back into the blood of the peritubular capillaries. This is about retention of useful substances.

- Mechanism: Involves both active transport of solutes and passive movement of water.

- Substances Reabsorbed: Critically important substances such as:

- Nutritive value: Glucose, amino acids, vitamins.

- Electrolytes: Na+, K+, Cl-, HCO3-.

- Special Case: Small Proteins & Peptide Hormones: These are reabsorbed in the proximal tubule by endocytosis (a form of active transport where the cell engulfs the substance). Once inside the cell, they are usually broken down into amino acids.

Tubular Secretion

The process of moving substances from the peritubular capillaries (or directly from the tubular cells) into the tubular lumen. This is about elimination of unwanted substances or fine-tuning plasma concentration.

- Mechanism: Primarily active transport, often utilizing specialized carriers.

- Purpose: Addition of a substance to the glomerular filtrate for excretion.

- Carrier Specificity: Many secretion carriers are relatively non-selective, meaning one carrier can transport several different, structurally related substances.

- Example: The carrier that secretes para-aminohippurate (PAH) can also secrete other organic acids like uric acid, bile acids, penicillin, probenecid, cephalothin, and furosemide. This highlights potential drug-drug interactions where one drug can compete with another for secretion, affecting its elimination.

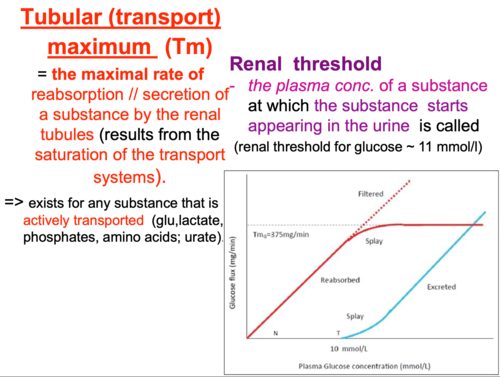

Renal Tubular Transport Maximum (Tm)

The maximum rate (amount per minute) at which a specific substance can be actively transported (either reabsorbed or secreted) by the renal tubules. It reflects the saturation point of the carrier proteins involved in active transport.

When the filtered load of a substance (concentration in plasma * GFR) exceeds the capacity of its specific transporters, the transporters become saturated, and the excess substance is unable to be transported.

Tm-Limited Substances

These are substances transported by active transport.

- Examples of Tm-Limited Reabsorption: Glucose, amino acids, phosphate, sulfate, uric acid (though uric acid also undergoes secretion), acetoacetate, beta-hydroxybutyrate, albumin (via endocytosis).

No Tm (or high Tm)

Substances that are primarily transported by passive diffusion (their transport rate depends on concentration gradients, not carrier saturation) or have such a high transport capacity that saturation is rarely reached under normal physiological conditions.

- Examples: Urea (passive reabsorption), creatinine (passive filtration and secretion), Na+ (reabsorbed actively, but the active reabsorption rate is so high and tightly regulated that it's often not considered "Tm-limited" in the same way as glucose; rather, it's regulated by overall body fluid and electrolyte balance). HCO3- reabsorption is also highly regulated but not in a classical Tm-limited fashion at physiological concentrations.

Transport Across Nephron Segments

I. Proximal Tubule (PT)

The Proximal Tubule (PT) is the workhorse of reabsorption, reclaiming the bulk of the filtered substances. Non-regulated reabsorption of the majority of filtered water and solutes.

- ~67% of filtered water, Na+, Cl-, K+, and other solutes.

- 100% of filtered glucose & amino acids. This prevents the loss of vital nutrients in urine under normal conditions.

Substances NOT Reabsorbed:

- Inulin, Creatinine, Sucrose, Mannitol: These are important because they are used as markers for GFR measurement (inulin, creatinine) or to induce osmotic diuresis (mannitol). Their non-reabsorption means their excretion rate reflects their filtration rate.

- H+ (coupled to Na+ reabsorption), PAH (para-aminohippurate), Urate, Penicillin, Sulphonamides, Creatinine (a small amount). This is vital for acid-base balance and eliminating waste products and drugs.

Mechanisms of Na+ Reabsorption in the PT:

Sodium reabsorption is a two-step process driven by the Na+-K+-ATPase pump on the basolateral membrane. This pump actively moves 3 Na+ ions out of the cell (into the interstitial fluid) and 2 K+ ions into the cell, creating:

- A low intracellular Na+ concentration.

- A negative intracellular potential.

These two gradients (chemical and electrical) provide the driving force for Na+ entry across the apical membrane.

a) In Early PT (S1 and S2 segments): Cotransport with H+/organic solutes.

Apical Membrane (Lumen to Cell): Na+ moves down its electrochemical gradient into the cell, coupled with other substances.

Na+-H+ Antiporter (NHE3)

This is a crucial transporter. Na+ moves into the cell, and H+ moves into the lumen.

- Linked to HCO3- Reabsorption: The secreted H+ combines with filtered HCO3- in the lumen to form H2CO3, which then dissociates into H2O and CO2 (catalyzed by luminal carbonic anhydrase). CO2 diffuses into the cell, where it combines with H2O to form H2CO3, which then dissociates into H+ (recycled by NHE3) and HCO3-. This HCO3- then exits the basolateral membrane into the blood. Therefore, Na+-H+ exchange is essential for reclaiming filtered bicarbonate.

- Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors (e.g., Acetazolamide): These drugs inhibit the enzyme, preventing the formation of CO2 and H2O from H2CO3 in the lumen and thus hindering HCO3- reabsorption. This leads to increased HCO3- and Na+ excretion, causing a metabolic acidosis and diuresis.

Na+-Glucose Symporter (SGLT)

This is the primary mechanism for glucose reabsorption. Na+ moves down its gradient, pulling glucose into the cell against its gradient. Similar symporters exist for amino acids, phosphate, and lactate.

- Transtubular Osmotic Gradient: As these solutes (especially Na+, glucose, amino acids) are actively reabsorbed, the tubular fluid becomes hypotonic relative to the intracellular fluid and interstitial fluid. This creates an osmotic gradient that drives the passive reabsorption of water (via aquaporin-1 channels and paracellularly).

Effect on Cl- Concentration: Because more water is reabsorbed in early PT than Cl- (which is initially reabsorbed to a lesser extent than Na+), the Cl- concentration in the tubular fluid rises along the length of the early PT. This sets up a gradient for Cl- reabsorption in the late PT.

b) In Late PT (S3 segment):

- Primary Mechanism: Chloride-driven sodium transport (both transcellular & paracellular).

- Key Characteristic: Fluid entering the late PT has a very low concentration of glucose, amino acids, and HCO3- (as these were largely reabsorbed earlier). Crucially, it has a high concentration of Cl- (up to 140 mEq/L, compared to ~105 mEq/L at the beginning of the PT).

- Paracellular Cl- & Na+ Reabsorption:

- This high luminal Cl- concentration creates a concentration gradient favoring the diffusion of Cl- from the lumen, through the "leaky" tight junctions, into the lateral intercellular space.

- As Cl- moves out of the lumen, it makes the lumen slightly electropositive relative to the interstitial fluid.

- This positive charge in the lumen then provides an electrical driving force for Na+ to diffuse paracellularly from the lumen into the blood.

- Transcellular Cl- & Na+ Reabsorption (Apical Membrane):

- Na+-H+ Antiporter: Still present and active.

- Cl--Anion Exchangers: One or more Cl- anion antiporters (e.g., Cl- with formate, oxalate, or other organic anions) facilitate Cl- entry into the cell.

- Basolateral Membrane (Cell to Interstitial Fluid):

- Na+-K+-ATPase pump: Continues to pump Na+ out.

- K+-Cl- Cotransporter: Cl- leaves the cell into the interstitial fluid via this cotransporter (or by Cl- channels).

II. Loop of Henle (LOH)

The Loop of Henle is critical for establishing the medullary osmotic gradient, which is essential for concentrating urine.

- Overall Function: Creates a concentrated interstitial fluid in the renal medulla.

- Key Reabsorption Figures:

- ~20% of filtered Na+ and Cl-.

- ~15% of filtered water.

- Cations: K+, Ca2+, Mg2+.

Segments of the LOH:

a) Thin Descending Limb (TDLOH):

- Permeability: Highly permeable to water, but relatively impermeable to solutes (Na+, Cl-).

- Mechanism: As the filtrate descends into the hypertonic medulla, water moves passively out of the tubule into the interstitial fluid by osmosis.

- Result: The tubular fluid becomes progressively more concentrated (hypertonic) as it moves down the descending limb.

- Diffusion of Na+: A small amount of Na+ can diffuse from the hypertonic interstitial fluid into the tubular lumen (down its concentration gradient), contributing to the concentration of the filtrate.

b) Thin Ascending Limb (TALOH):

- Permeability: Highly permeable to solutes (Na+, Cl-), but largely impermeable to water.

- Mechanism: Passive diffusion of Na+ and Cl- out of the tubule into the interstitial fluid, driven by their concentration gradients (established by water reabsorption in the TDLOH).

- Result: The tubular fluid becomes less concentrated (hypotonic) as it moves up the ascending limb.

c) Thick Ascending Limb (TAL):

- Permeability: Impermeable to water. This is crucial for diluting the tubular fluid.

- Key Reabsorption: Reabsorbs ~20-25% of filtered Na+, Cl-, and other cations (K+, Ca2+, Mg2+).

- Mechanisms of Na+ Reabsorption:

- Transcellular Active Reabsorption (~50% of Na+):

- Basolateral Membrane: Na+-K+-ATPase pump actively extrudes Na+ into the interstitial fluid, creating a low intracellular Na+ concentration.

- Apical Membrane: Na+-K+-2Cl- Symporter (NKCC2 transporter): This is the key transporter in the TAL. It moves 1 Na+, 1 K+, and 2 Cl- ions from the tubular lumen into the cell. This is a secondary active transport system, driven by the Na+ gradient.

- Loop Diuretics (e.g., Furosemide, Ethacrynic Acid): These drugs inhibit the NKCC2 symporter, preventing the reabsorption of Na+, K+, and Cl-. This leads to a significant increase in water and electrolyte excretion, hence their potent diuretic effect.

- K+ Recycling: Some of the K+ entering the cell via NKCC2 leaks back into the lumen via K+ channels. This "K+ recycling" is crucial for maintaining the K+ concentration in the lumen, ensuring continued operation of the NKCC2 symporter.

- Lumen-Positive Potential: The back-diffusion of K+ into the lumen, combined with the net reabsorption of negative charge (Cl-), creates a lumen-positive transepithelial potential difference (+6 to +10 mV).

- Paracellular Passive Reabsorption (~50% of Na+ and other cations):

- The lumen-positive potential generated by K+ recycling and active transport in the TAL provides the driving force for the paracellular reabsorption of positively charged ions like Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ through the tight junctions. This mechanism is critical for reclaiming these important cations.

- Na+-H+ Antiporter: Also present in the TAL, contributing to H+ secretion and HCO3- reabsorption.

- Transcellular Active Reabsorption (~50% of Na+):

III. Distal Tubule (DT) & Collecting Duct (CD)

These segments are responsible for the fine-tuning of electrolyte and water balance, largely under hormonal control.

- Overall Function: Regulated reabsorption of remaining Na+, Cl-, and water, and regulated secretion of K+ and H+.

- Key Reabsorption Figures:

- ~7% of filtered NaCl.

- ~8-17% of filtered water.

- Key Secretion Figures:

- K+ and H+.

a) Early Distal Tubule (DCT1 or Cortical Diluting Segment):

- Permeability: Impermeable to water.

- Key Reabsorption: Reabsorbs Na+ and Cl-.

- Mechanism:

- Apical Membrane: Na+-Cl- Symporter (NCC transporter). Na+ and Cl- move into the cell.

- Basolateral Membrane: Na+-K+-ATPase pumps Na+ out, and Cl- leaves via Cl- channels or cotransporters.

- Result: Since water cannot follow the reabsorbed solutes, the tubular fluid becomes even more dilute as it passes through this segment. Hence, it's called the "cortical diluting segment."

- Thiazide Diuretics: These drugs inhibit the NCC symporter, reducing NaCl reabsorption, leading to increased water and electrolyte excretion.

b) Late Distal Tubule (DCT2) and Collecting Duct (CD):

This segment contains two main cell types, and their function is highly regulated by hormones, particularly Aldosterone and Antidiuretic Hormone (ADH).

i. Principal Cells:

- Function: Reabsorb Na+ and water, and secrete K+.

- Na+ Reabsorption:

- Basolateral Membrane: Na+-K+-ATPase pump actively moves Na+ out of the cell.

- Apical Membrane: Na+ enters the cell from the lumen via Epithelial Sodium Channels (ENaC), moving down its electrochemical gradient. This makes the lumen negatively charged.

- Cl- Reabsorption: Primarily via the paracellular pathway, driven by the lumen-negative charge created by Na+ influx.

- Water Reabsorption:

- Apical Membrane: Presence of Aquaporin-2 (AQP2) water channels.

- ADH (Vasopressin) Role: ADH binds to receptors on the principal cells, triggering the insertion of AQP2 channels into the apical membrane. This makes the cells permeable to water, allowing water to move by osmosis into the hypertonic medullary interstitium.

- Absence of ADH: In the absence of ADH, AQP2 channels are withdrawn, and the principal cells are essentially impermeable to water. This results in the excretion of dilute urine.

- K+ Secretion:

- Basolateral Membrane: K+ is actively pumped into the cell by the Na+-K+-ATPase.

- Apical Membrane: K+ then diffuses out of the cell into the lumen via K+ channels (ROMK channels).

- Factors influencing K+ secretion: Luminal fluid flow rate, luminal Na+ concentration, and especially Aldosterone.

ii. Intercalated Cells (Alpha and Beta):

- Alpha-Intercalated Cells: Primarily responsible for H+ secretion (via H+-ATPase and H+-K+-ATPase on the apical membrane) and K+ reabsorption (via H+-K+-ATPase on the apical membrane). Important for acid-base balance.

- Beta-Intercalated Cells: Primarily secrete HCO3- and reabsorb H+. (Less common focus in general overviews).

- Mechanism: Aldosterone, a steroid hormone, enters the principal cell and binds to intracellular receptors. This complex then acts as a transcription factor, increasing the synthesis and insertion of:

- ENaC channels on the apical membrane, increasing Na+ reabsorption.

- Na+-K+-ATPase pumps on the basolateral membrane, increasing Na+ extrusion and K+ uptake.

- ROMK channels on the apical membrane, increasing K+ secretion.

- Overall Effect: Increases Na+ reabsorption and increases K+ secretion.

- Timeframe: This process takes several hours to manifest because it involves protein synthesis.

- Magnitude: Aldosterone significantly influences Na+ and K+ balance, though it affects a smaller percentage of overall filtered Na+ than the PT or LOH.

Role of Aldosterone on Intercalated Cells (specifically Alpha-Intercalated):

- Effect: Aldosterone stimulates the H+-ATPase pump on the apical membrane of alpha-intercalated cells, thereby increasing H+ secretion into the lumen (and K+ reabsorption). This is vital for regulating acid-base balance.

Water Reabsorption

Always occurs by osmosis, following the osmotic gradients created by solute reabsorption.

- Channels: Water moves through specialized water channels called aquaporins.

- Aquaporin-1 (AQP1): Constitutively expressed in the proximal tubule and descending limb of the Loop of Henle.

- Aquaporin-2 (AQP2): Regulated by ADH in the collecting ducts.

- Other aquaporins (e.g., AQP3, AQP4) are on the basolateral membranes of collecting duct cells.

- Segmental Breakdown:

- PT: ~67% of filtered water reabsorbed (passively, via AQP1).

- LOH:

- Descending Thin Segment: ~15% reabsorbed (passively, via AQP1).

- Ascending Limbs (Thin & Thick): Impermeable to water. This is crucial for diluting the tubular fluid and establishing the medullary gradient.

- DT & CD: ~8-17% reabsorbed.

- Distal Convoluted Tubule (Early DT) & Connecting Tubule (CNT): Impermeable to water.

- Cortical, Outer, & Inner Medullary CD: Water reabsorption here is entirely dependent on ADH.

Obligatory Reabsorption (Must Reabsorb)

The portion of water reabsorbed that is not under hormonal control and occurs automatically in response to osmotic gradients.

- Amount: Approximately 85% of filtered water.

- Location: Occurs in the PT (~67%) and the descending limb of LOH (~15-18%).

- Mechanism: Driven by the reabsorption of solutes (especially Na+) creating an osmotic gradient.

Facultative Reabsorption (Optional/Regulated)

The portion of water reabsorbed that is under hormonal control, allowing the body to adjust urine volume and concentration based on hydration status.

- Amount: The remaining 15-18% of water.

- Location: Occurs primarily in the Collecting Ducts.

- Control: Entirely dependent on ADH.

Regulation of K+ Tubular Secretion

Potassium balance is tightly regulated, mainly through controlled secretion in the late DT and CD.

- Plasma K+ Level (Most Important):

- Hyperkalemia (High Plasma K+): Directly stimulates K+ secretion by principal cells.

- Increases K+ channels on the apical membrane.

- Increases Na+-K+-ATPase activity on the basolateral membrane.

- Hypokalemia (Low Plasma K+): Decreases K+ secretion.

- Hyperkalemia (High Plasma K+): Directly stimulates K+ secretion by principal cells.

- Aldosterone (Crucial Hormonal Control):

- Stimuli for Aldosterone Release: Hyperkalemia (most potent direct stimulus), Angiotensin II.

- Effects of Aldosterone (on Principal Cells):

- Increases Na+-K+-ATPase activity: More K+ pumped into the cell.

- Increases Na+ entry into cells (via ENaC): This makes the tubular lumen more negative (lumen-negative transepithelial potential difference - TEPD).

- Increases permeability of the apical membrane to K+ (more K+ channels).

- Combined Result: All these actions dramatically increase the driving force for K+ to move from the cell into the tubular lumen, thus increasing K+ secretion.

- Glucocorticoids (Indirect Effect):

- Glucocorticoids (e.g., cortisol) can have a mineralocorticoid-like effect (like aldosterone) if present in high concentrations.

- They can also indirectly increase K+ excretion by increasing GFR, which increases tubular fluid flow rate.

- Tubular Fluid Flow Rate:

- High Flow Rate (e.g., during diuretic use, osmotic diuresis):

- "Washes away" secreted K+ more quickly, maintaining a steep concentration gradient for K+ between the cell and the lumen.

- Increases the activity of K+ channels.

- Result: Increases K+ secretion. This is why many diuretics (especially loop and thiazide diuretics, which increase fluid delivery to the late DT/CD) can cause hypokalemia.

- Low Flow Rate (e.g., during dehydration): Decreases K+ secretion.

- High Flow Rate (e.g., during diuretic use, osmotic diuresis):

- ADH (Antidiuretic Hormone): ADH has complex and sometimes opposing effects on K+ secretion.

- Indirect Stimulatory Effect: By increasing water reabsorption in the collecting duct, ADH concentrates the Na+ in the lumen. This increased Na+ uptake creates a more lumen-negative potential, which can favor K+ secretion.

- Indirect Inhibitory Effect: If ADH leads to a very low tubular flow rate (concentrating the urine), it might reduce the "wash away" effect of K+, potentially decreasing K+ secretion.

- Overall: The combination of these effects typically maintains K+ secretion relatively constant despite changes in water excretion.

Diuretics

Diuretics are pharmacological agents that increase the rate of urine flow, primarily by increasing the excretion of solutes, which in turn leads to increased water excretion. The term "water pills" aptly describes their main function. Antidiuretics, conversely, reduce water excretion (e.g., Vasopressin/ADH).

- Heart Failure: Reduce fluid overload, decreasing cardiac workload and pulmonary congestion.

- Liver Cirrhosis (with ascites): Manage fluid accumulation in the abdomen.

- Hypertension (High Blood Pressure): Reduce blood volume and, for some, exert vasodilatory effects.

- Kidney Diseases: Manage edema and fluid overload in certain renal conditions.

- Cerebral Edema/Increased Intracranial Pressure: Especially osmotic diuretics.

- Glaucoma: Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors reduce aqueous humor production.

- Altitude Sickness: Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors.

- Pregnancy-Associated Edema: Used cautiously.

- Drug Overdose/Poisoning: To increase excretion of certain substances (e.g., aspirin with acetazolamide to alkalinize urine).

Classes of Diuretics

I. High Ceiling / Loop Diuretics

- Examples: Furosemide (Lasix), Bumetanide (Bumex), Torasemide (Demadex), Ethacrynic acid (Edecrin).

- Site of Action: Thick Ascending Limb of the Loop of Henle (TAL).

- Mechanism of Action:

- Inhibit the Luminal Na+/K+/2Cl- Symporter (NKCC2 transporter): This is their primary mechanism. By blocking this transporter, loop diuretics prevent the reabsorption of a significant amount of filtered Na+, K+, and Cl-.

- Impair Medullary Concentrating Ability: By inhibiting solute reabsorption in the TAL, they disrupt the countercurrent multiplier system, reducing the osmolarity of the medullary interstitium. This means less water can be reabsorbed from the collecting ducts, leading to a large increase in urine volume.

- Lumen-Positive Potential: They also abolish the lumen-positive potential in the TAL, which normally drives the paracellular reabsorption of Ca2+ and Mg2+. This explains why loop diuretics can increase the excretion of these cations.

- Renal Prostaglandins: Increase the synthesis of renal prostaglandins, which contribute to vasodilation of renal afferent arterioles, increasing renal blood flow and further enhancing diuretic effect. This also leads to reduced peripheral vascular resistance.

- Efficacy ("High Ceiling"): They are the most potent diuretics because the TAL reabsorbs a large fraction (~20-25%) of filtered Na+ and Cl-. Thus, blocking this reabsorption leads to a substantial increase in electrolyte and water excretion.

- Side Effects:

- Electrolyte Imbalances: Hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia (due to increased excretion of these ions).

- Metabolic Alkalosis: Due to increased H+ secretion in distal segments and increased HCO3- reabsorption.

- Ototoxicity: Hearing loss, especially with rapid IV administration or in combination with other ototoxic drugs (e.g., aminoglycosides).

- Dehydration and Hypotension: Due to massive fluid loss.

II. Thiazide Diuretics

- Examples: Hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ - Esidrix, HydroDIURIL), Chlorothiazide (Diuril), Chlorthalidone, Indapamide, Metolazone.

- Site of Action: Early Distal Convoluted Tubule (DCT).

- Mechanism of Action:

- Inhibit the Luminal Na+/Cl- Symporter (NCC transporter): This prevents the reabsorption of Na+ and Cl- in the DCT.

- Less Potent than Loop Diuretics: The DCT reabsorbs only about 5-10% of filtered Na+, making thiazides less potent than loop diuretics.

- Diluting Segment: Like loop diuretics, they impair the kidney's ability to dilute urine (by inhibiting Na+/Cl- reabsorption in a water-impermeable segment), contributing to increased water excretion.

- Decreased Calcium Excretion ("Calcium-Sparing"): This is a unique and important effect. Thiazides increase the reabsorption of Ca2+ in the DCT. This is thought to be partly due to increased activity of the basolateral Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, which is driven by increased intracellular Na+ (due to NCC inhibition) and facilitated by the lumen-negative potential. This property makes them useful for treating hypercalciuria (excess calcium in urine) and preventing kidney stones.

- Antihypertensive Action:

- Short-term: Decrease blood volume, leading to decreased cardiac output and therefore decreased blood pressure.

- Long-term: Exert a direct vasodilatory effect on peripheral arterioles, which reduces peripheral vascular resistance. This effect is independent of their diuretic action.

- Side Effects:

- Electrolyte Imbalances: Hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypercalcemia (due to decreased excretion), hyponatremia.

- Metabolic Alkalosis.

- Hyperuricemia: May precipitate gout attacks by decreasing uric acid excretion.

- Hyperglycemia: Impair glucose tolerance in some patients.

- Dyslipidemia.

III. Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors (CAIs)

- Examples: Acetazolamide (Diamox), Methazolamide (Neptazane).

- Site of Action: Primarily Proximal Convoluted Tubule (PT).

- Mechanism of Action:

- Inhibit Carbonic Anhydrase Enzyme: This enzyme is crucial in the PT for:

- Luminal Side: Converting H2CO3 into H2O and CO2, allowing CO2 to diffuse into the cell.

- Cytoplasmic Side: Converting CO2 and H2O back into H2CO3, which then dissociates into H+ and HCO3-.

- Decreased H+ Secretion: By inhibiting cytoplasmic carbonic anhydrase, less H+ is available for the Na+/H+ antiporter on the apical membrane.

- Decreased HCO3- Reabsorption: Less H+ secretion means less HCO3- can be reclaimed. Bicarbonate accumulates in the tubular lumen and is excreted.

- Decreased Na+ Reabsorption: Since Na+ reabsorption in the PT is strongly coupled to H+ secretion via the Na+/H+ antiporter, inhibition leads to decreased Na+ reabsorption and therefore increased Na+ and water excretion.

- Inhibit Carbonic Anhydrase Enzyme: This enzyme is crucial in the PT for:

- Diuretic Efficacy: Relatively weak diuretics because the body has compensatory mechanisms further down the nephron to reabsorb Na+.

- Clinical Uses (beyond diuresis):

- Glaucoma: Reduce aqueous humor production in the eye, lowering intraocular pressure.

- Metabolic Alkalosis: Excrete bicarbonate to correct the alkalosis.

- Altitude Sickness: Induce metabolic acidosis, which stimulates respiration and helps acclimatization.

- Alkalinization of Urine: Increase the excretion of acidic drugs like aspirin in overdose.

- Side Effects:

- Metabolic Acidosis: Due to increased bicarbonate excretion.

- Hypokalemia: Increased Na+ delivery to the collecting duct can lead to increased K+ secretion.

- Renal Stones: Due to increased calcium phosphate and cysteine excretion in alkaline urine.

- Sulfonamide Allergy: Many CAIs are sulfonamide derivatives.

IV. Potassium-Sparing Diuretics (KSDs)

- Examples:

- Aldosterone Antagonists: Spironolactone (Aldactone), Eplerenone.

- ENaC Blockers (Sodium Channel Blockers): Amiloride (Midamor), Triamterene (Dyrenium).

- Site of Action: Late Distal Tubule (DCT2) and Collecting Duct.

- Mechanism of Action (The key feature: "Sparing Potassium"):

- They interfere with the Na+/K+ exchange in the principal cells of the late DCT and CD, either by blocking aldosterone's effects or directly blocking Na+ channels. This prevents K+ secretion and leads to K+ retention.

- Sub-Classes:

- a) Aldosterone Antagonists:

- Mechanism: Competitively bind to and block aldosterone receptors in the principal cells. This prevents aldosterone from:

- Increasing ENaC channel insertion (reducing Na+ reabsorption).

- Increasing Na+/K+-ATPase activity (reducing Na+ reabsorption and K+ secretion).

- Increasing K+ channel insertion (reducing K+ secretion).

- Result: Decreased Na+ and water reabsorption, and decreased K+ secretion (K+ is spared).

- Clinical Uses: Often used in combination with loop or thiazide diuretics to counteract their K+-wasting effects. Beneficial in conditions with hyperaldosteronism (e.g., cirrhosis, heart failure).

- Side Effects: Hyperkalemia (most dangerous), metabolic acidosis, antiandrogenic effects (gynecomastia, menstrual irregularities with spironolactone).

- Mechanism: Competitively bind to and block aldosterone receptors in the principal cells. This prevents aldosterone from:

- b) ENaC Blockers (Sodium Channel Blockers):

- Mechanism: Directly block the Epithelial Sodium Channels (ENaC) on the apical membrane of principal cells.

- Result: Reduces Na+ entry into the cell, which in turn:

- Reduces the activity of the basolateral Na+/K+-ATPase.

- Reduces the electrochemical gradient that drives K+ secretion.

- Makes the tubular lumen less negative, further reducing the driving force for K+ secretion.

- Result: Decreased Na+ and water reabsorption, and decreased K+ secretion (K+ is spared).

- Clinical Uses: Similar to aldosterone antagonists, often used with other diuretics to prevent hypokalemia.

- Side Effects: Hyperkalemia (most dangerous), metabolic acidosis.

- a) Aldosterone Antagonists:

V. Osmotic Diuretics

- Examples: Mannitol, Urea, Glycerin, Isosorbide. (Glucose is an osmotic diuretic in uncontrolled diabetes but not used therapeutically as one).

- Site of Action: Primarily Proximal Tubule, Loop of Henle, Collecting Duct (anywhere permeable to water).

- Mechanism of Action:

- Pharmacologically Inert, Freely Filtered: These are low molecular weight substances that are freely filtered at the glomerulus.

- Limited Tubular Reabsorption: They have high water solubility and limited reabsorption (or are completely non-reabsorbable) by the tubular epithelial cells.

- Osmotically Active: Their presence in the tubular lumen creates an osmotic gradient.

- "Pulls Water": As they pass along the nephron, they "pull" water with them by osmosis, preventing its reabsorption.

- Expand ECF and Plasma Volume: Initially, they draw water from intracellular spaces into the extracellular fluid and plasma, increasing circulating blood volume.

- Increased Renal Blood Flow: This initial expansion can increase blood flow to the kidney, potentially increasing GFR and medullary wash-out.

- Impairs Urine Concentration: By increasing flow rate and reducing the medullary osmotic gradient (wash-out effect), they impair the kidney's ability to concentrate urine.

- Clinical Uses:

- Cerebral Edema / Increased Intracranial Pressure: Draw water out of the brain.

- Acute Glaucoma: Draw water out of the eye.

- Acute Renal Failure: To maintain urine flow and prevent anuria in certain situations.

- Side Effects:

- Dehydration and Hypovolemia (if water is not replaced).

- Hyponatremia / Hypernatremia: Depending on fluid balance.

- Pulmonary Edema: Due to initial plasma volume expansion (contraindicated in severe heart failure).

- Headache, Nausea, Vomiting.

Additional Classifications Mentioned:

- Low Ceiling Diuretics: Generally refers to diuretics that have a flatter dose-response curve and reach a maximal effect at lower doses compared to "high ceiling" loop diuretics. Thiazides are often classified as low-ceiling diuretics.

- Calcium-Sparing Diuretics:

- Thiazides: As discussed, they decrease calcium excretion by increasing its reabsorption.

- K+ Sparing Diuretics: Some K+ sparing diuretics (especially ENaC blockers like amiloride/triamterene) can also reduce Ca2+ excretion, though their effect is less pronounced and less direct than thiazides. Aldosterone antagonists have little direct effect on calcium handling.

https://www.doctorsrevisionuganda.com | Whatsapp: 0726113908

Kidney, GFR, Haemodynamics and Diuretics

Systems Physiology

Enter your details to begin the examination.

🛡️ Privacy Note: Results are for tracking and certification purposes only.

Kidney, GFR, Haemodynamics and Diuretics

Systems Physiology

Preparing questions...

Exam Completed!

See your performance breakdown below.