Parathyroid Gland & Calcium Metabolism

INTRODUCTION TO CALCIUM METABOLISM

Calcium (Ca²⁺) is the most abundant mineral in the human body, playing a pivotal role far beyond its primary association with bone health. It is an indispensable second messenger in virtually every cell, a key player in nerve impulse transmission, muscle contraction, and blood coagulation. Similarly, phosphate (PO₄³⁻) is a crucial component of bones, cell membranes (phospholipids), genetic material (DNA, RNA), and energy currency (ATP).

The body maintains extremely tight control over the levels of these ions, particularly calcium, in the extracellular fluid (ECF) and plasma. Deviations, even slight ones, can have profound and immediate physiological consequences. This section will explore the regulation of calcium and phosphate, their distribution in the body, and the critical physiological roles they play.

CALCIUM REGULATION IN ECF AND PLASMA

The concentration of calcium ions in the extracellular fluid (ECF) and plasma is precisely and tightly regulated. It rarely deviates significantly from normal levels, highlighting its critical importance for life.

- Normal Value: The normal value of total calcium in the ECF is approximately 9.4 mg/dL (or 2.4 mEq/L). This represents a very small fraction, about 0.1%, of the total calcium in the body.

- Vital Physiological Processes: Calcium ions are absolutely vital to numerous physiological processes, including:

- Contraction of muscles: Essential for the excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscles.

- Blood clotting: A critical cofactor in several steps of the coagulation cascade, facilitating the formation of a stable blood clot.

- Transmission of nerve impulses: Involved in the release of neurotransmitters from presynaptic terminals and influencing neuronal excitability.

- Enzyme activation, hormone secretion, and cell signaling.

- Impact of Deviations: Any significant deviations from the normal ECF calcium levels have immediate and direct effects:

- Low Ca²⁺ (Hypocalcemia): Directly excites neuromuscular systems, leading to increased neuronal excitability, tetany, and muscle spasms.

- High Ca²⁺ (Hypercalcemia): Directly depresses neuromuscular and cardiac systems, leading to muscle weakness, lethargy, and cardiac arrhythmias.

- Distribution of Total Body Calcium:

- Approximately 99% of total body calcium is stored in the bones, serving as a large and readily available reservoir.

- About 1% of total calcium is found in cells, where it functions as a crucial intracellular messenger. The remaining very small fraction is in the ECF and plasma.

CALCIUM IN PLASMA AND INTERSTITIAL FLUID

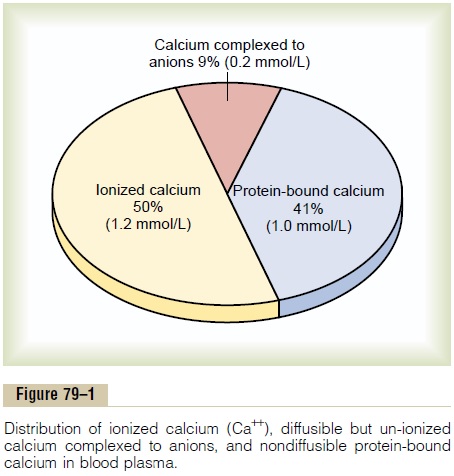

In plasma and interstitial fluid, calcium exists in three distinct forms, contributing to the total calcium level:

- 41% Combined with Plasma Proteins: This fraction is primarily bound to albumin and, to a lesser extent, globulins. This protein-bound calcium is non-diffusible through capillary membranes and therefore not physiologically active in terms of directly influencing cell excitability.

- 9% Diffusible, Combined with Anionic Substances: This portion is bound to various anionic substances present in plasma and interstitial fluid, such as citrates and phosphates. This calcium is diffusible across capillary membranes but is not ionized, meaning it is not biologically active in the same way as free calcium ions.

- 50% Diffusible and Ionized (Free Ca²⁺): This is the most crucial form of calcium. It is diffusible across capillary membranes and, most importantly, exists as free calcium ions (Ca²⁺). This ionized calcium is the physiologically active form that participates in muscle contraction, nerve impulse transmission, blood clotting, and other vital cellular processes. Its normal level in plasma is approximately 1.2 mmol/L (or 2.4 mEq/L), which corresponds to roughly 4.7 mg/dL.

The ionized calcium fraction is the one that is tightly regulated by hormones like parathyroid hormone (PTH), vitamin D, and calcitonin.

PHOSPHATE REGULATION IN ECF AND PLASMA

Phosphate is also a vital mineral, but its regulation in the ECF is generally less precise and less tightly controlled than calcium.

- Distribution of Total Body Phosphate:

- Approximately 85% of the body's phosphate is found in bones, predominantly as hydroxyapatite crystals.

- 14-15% is located within cells, where it is integral to intracellular processes (e.g., ATP, DNA, RNA, phospholipids).

- Less than 1% is in the ECF, indicating its relatively minor extracellular presence compared to its intracellular and bone stores.

- ECF Concentration: The concentration of inorganic phosphate in the ECF is typically around 4 mg/dL. This level can vary slightly:

- Adults: Generally 3 to 4 mg/dL.

- Children: Tend to have slightly higher levels, typically 4 to 5 mg/dL, due to higher growth rates.

- Forms in ECF: Inorganic phosphate exists in the ECF in two primary forms:

- HPO₄²⁻ (Divalent Phosphate Ion): Approximately 1.05 mmol/L.

- H₂PO₄⁻ (Monovalent Phosphate Ion): Approximately 0.26 mmol/L.

- Relationship with pH:

- An increase in total ECF phosphate will generally increase the concentrations of both forms.

- A low pH (acidosis) increases the concentration of H₂PO₄⁻ and decreases HPO₄²⁻.

- A high pH (alkalosis) has the reverse effect, increasing HPO₄²⁻ and decreasing H₂PO₄⁻.

- Regulation: Although less tightly regulated than calcium, many of the same factors that regulate ECF calcium concentration (e.g., PTH, Vitamin D) also influence phosphate levels, mainly by affecting its renal excretion and intestinal absorption.

NON-BONE EFFECTS OF ALTERED CA AND PHOSPHATE CONCENTRATIONS IN THE BODY FLUIDS

The immediate physiological impact of altered calcium and phosphate levels differs significantly:

- Phosphate: Changing the level of phosphate in the ECF from far below normal to two to three times normal does not cause major immediate effects on the body. While chronic alterations can have serious consequences, acute changes are often well-tolerated because most phosphate is intracellular or in bone.

- Calcium: In stark contrast, even slight increases or decreases of ionized calcium in the ECF can cause extreme immediate physiological effects. This underscores the body's meticulous regulatory mechanisms for calcium.

- Hypocalcemia: (Low ECF ionized calcium) leads to increased neuromuscular excitability, manifesting as tetany, muscle cramps, tingling, and potentially seizures.

- Hypercalcemia: (High ECF ionized calcium) leads to depressed neuromuscular activity, manifesting as muscle weakness, lethargy, constipation, confusion, and cardiac arrhythmias.

Hence, clinical conditions are primarily discussed in terms of:

- Hypocalcemia vs. Hypercalcemia (which are acutely life-threatening due to effects on excitable tissues)

- Hypophosphatemia vs. Hyperphosphatemia (which tend to have more chronic and metabolic implications, rather than immediate severe effects on excitability).

ALTERED CALCIUM LEVELS

HYPOCALCEMIA

Hypocalcemia occurs when the extracellular fluid (ECF) calcium ion concentration falls below its normal range (normally 9.4 mg/dL). This condition has profound and immediate effects on the nervous and muscular systems due to the role of calcium in regulating cell excitability.

- Increased Nervous System Excitability: As ECF [Ca²⁺] falls, the nervous system becomes progressively more excitable. This is because calcium ions normally stabilize nerve membranes. When calcium is low, nerve fibers become more permeable to sodium ions, making them more likely to depolarize and fire action potentials spontaneously.

- Tetany: At about 6 mg/dL (approximately 50% below the normal ionized calcium level), the peripheral nerve fibers become so excitable that they begin to fire spontaneously, causing generalized muscle contractions known as tetanic contractions (tetany). This can manifest as carpopedal spasm (spasms of the hands and feet) and laryngospasm (spasm of the vocal cords, which can be life-threatening).

- Seizures: Hypocalcemia can also lead to seizures due to its action of increasing excitability in the brain.

- Lethal Level: If ECF [Ca²⁺] drops to about 4 mg/dL, severe hypocalcemia can lead to respiratory arrest (due to laryngospasm or severe muscle spasms) and cardiac arrhythmias, resulting in death.

HYPERCALCEMIA

Hypercalcemia occurs when the level of calcium in the body fluids rises above normal. Unlike hypocalcemia, which excites the nervous system, hypercalcemia tends to depress it.

- Depressed Nervous System: The nervous system becomes depressed, and reflex activities of the central nervous system (CNS) become sluggish. This is because high calcium levels decrease the permeability of nerve membranes to sodium ions, making them less excitable.

- Cardiac Effects: Hypercalcemia decreases the QT interval of the heart on an electrocardiogram (ECG), which can lead to arrhythmias.

- Gastrointestinal Effects: It can cause lack of appetite (anorexia) and constipation due to decreased smooth muscle activity in the gastrointestinal tract.

- Severity:

- Effects begin to appear at about 12 mg/dL.

- Become marked above 15 mg/dL.

- Very high levels (e.g., above 17 mg/dL) can lead to lethargy, coma, and cardiac arrest.

LINES OF DEFENCE FROM CHANGES IN [CA++]

The body employs two main lines of defense to prevent significant alterations in ECF calcium concentration, ensuring its tight regulation:

- Buffer Function of the Exchangeable Calcium in Bones—The First Line of Defense:

- Bones contain a large reservoir of calcium, a small portion of which is in a readily exchangeable form. This exchangeable calcium is in dynamic equilibrium with the ECF.

- If ECF [Ca²⁺] begins to fall, calcium can be rapidly released from this exchangeable pool in the bones into the ECF.

- Conversely, if ECF [Ca²⁺] rises, calcium can be rapidly taken up by the bone.

- This rapid exchange acts as an immediate, short-term buffer system to minimize acute fluctuations in ECF calcium.

- Hormonal Control of Calcium Ion Concentration—The Second Line of Defense:

- For long-term and fine-tuned regulation, the body relies on specific hormones that control calcium homeostasis. These hormones primarily act on the gut, kidneys, and bone.

- The three main hormones involved are:

- Parathyroid Hormone (PTH): The most critical regulator, increasing ECF [Ca²⁺].

- Calcitriol (active Vitamin D): Works synergistically with PTH, increasing intestinal absorption of calcium.

- Calcitonin: Generally decreases ECF [Ca²⁺], though its role in adult human calcium homeostasis is less dominant than PTH and Vitamin D.

ABSORPTION AND EXCRETION OF CA AND PHOSPHATE

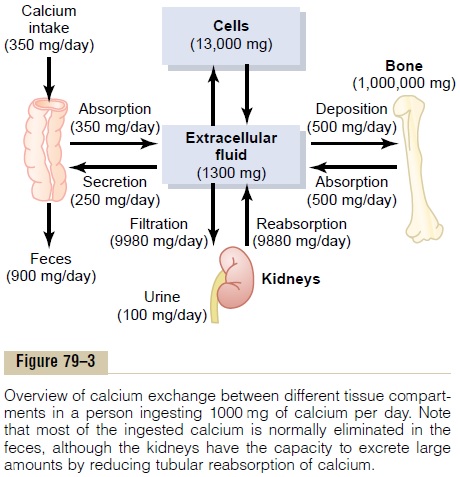

Calcium and phosphate balance in the body is a result of the interplay between:

- Intestinal Absorption: The uptake of these minerals from the diet into the bloodstream.

- Renal Excretion: The removal of excess minerals from the bloodstream via the kidneys into the urine.

- Bone Turnover: The continuous process of bone formation (deposition of calcium and phosphate) and bone resorption (release of calcium and phosphate) from the skeleton.

These processes are tightly regulated by the hormonal control system.

VITAMIN D

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin that plays a critical role in calcium and phosphate homeostasis. However, Vitamin D itself is not the active substance that directly causes these effects. Instead, it must be metabolized into its active form.

- Potent Effect: Its most potent and well-known effect is to increase calcium absorption from the intestinal tract.

SYNTHESIS AND METABOLISM OF VITAMIN D

Vitamin D exists in several forms and undergoes a series of hydroxylations to become biologically active:

- Sources of Precursor Vitamin D:

- Skin Synthesis: Vitamin D₃ (cholecalciferol) is synthesized in the skin when 7-dehydrocholesterol is exposed to ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation from sunlight.

- Dietary Sources:

- Vitamin D₂ (ergocalciferol): Obtained in the diet primarily from plant sources (e.g., fortified foods, some mushrooms).

- Vitamin D₃ (cholecalciferol): Also obtained in the diet from animal sources (e.g., fatty fish, fish liver oil, fortified dairy).

- First Hydroxylation (in the Liver):

- Both dietary Vitamin D₂ and D₃, as well as D₃ synthesized in the skin, are transported to the liver.

- In the liver, they undergo hydroxylation at the 25-position by the enzyme 25-hydroxylase, converting them into 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), also known as calcidiol.

- Calcidiol is the main circulating form of Vitamin D and is used as an indicator of a person's Vitamin D status.

- Second Hydroxylation (in the Kidney):

- Calcidiol (25(OH)D) then travels to the kidneys.

- In the kidneys, it is converted to the most active form, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)₂D), also known as calcitriol, by the enzyme 1-alpha-hydroxylase.

- This step is tightly regulated, primarily by Parathyroid Hormone (PTH). Elevated serum PTH increases the hydroxylation of Vitamin D in the kidney, thus increasing the production of calcitriol.

PHYSIOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF VITAMIN D (CALCITRIOL)

The active form of Vitamin D, calcitriol, has several critical physiological effects on calcium and phosphate homeostasis:

- Facilitates Intestinal Absorption: It is the primary hormone that facilitates the uptake of calcium from the intestinal epithelium into the bloodstream. This is its most crucial role in raising plasma calcium levels.

- Enhances Cellular Transport: It enhances the transport of calcium through and out of cells in various tissues, including the intestine and bone.

- Bone Turnover: It is important for normal bone turnover, working in concert with PTH to facilitate bone remodeling. While it promotes calcium and phosphate deposition into bone, it can also, under certain conditions (especially in the presence of PTH), mobilize calcium from bone.

- Promotes Phosphate Absorption: In addition to calcium, it also promotes phosphate absorption by the intestines, thereby increasing plasma phosphate levels.

- Decreases Renal Excretion: It decreases renal calcium and phosphate excretion, promoting their reabsorption in the kidneys and reducing their loss in urine. This also contributes to increasing plasma levels of both minerals.

PARATHYROID GLANDS

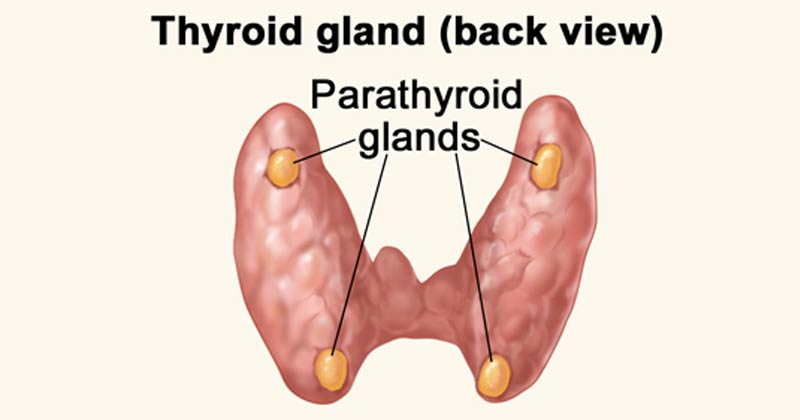

The parathyroid glands are small endocrine glands that play a central role in maintaining calcium homeostasis.

Physiological Anatomy of Parathyroid Glands:

- Number and Location: Humans typically have four parathyroid glands. They are located immediately behind the thyroid gland, with one gland situated behind each of the upper poles and each of the lower poles of the thyroid.

- Size and Appearance: Each parathyroid gland is quite small, typically about 6 mm long, 3 mm wide, and 2 mm thick. Macroscopically, they have a characteristic dark brown, fatty appearance, which can make them challenging to identify during surgery.

Histology of Parathyroid Glands:

The parathyroid gland of the adult human being primarily consists of two main cell types:

- Chief Cells (or Principal Cells):

- These are the most numerous cells and are believed to be responsible for secreting most, if not all, of the Parathyroid Hormone (PTH).

- They are characterized by a relatively clear cytoplasm in their inactive state and a more granular cytoplasm when actively synthesizing and secreting PTH.

- Oxyphil Cells:

- These cells are present in small to moderate numbers in adult human parathyroid glands.

- However, oxyphil cells are often absent in many animals and in young humans.

- Their function is not entirely certain, but they are generally believed to be modified or depleted chief cells that no longer secrete hormone. They typically appear later in life and increase with age.

PARATHYROID HORMONE (PTH)

Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) is the single most important hormone for the minute-to-minute regulation of ECF calcium concentration. It provides a powerful mechanism for controlling both ECF calcium and phosphate levels.

Chemistry:

- Polypeptide Structure: PTH is a polypeptide composed of 84 amino acids. It has a molecular weight (MW) of approximately 9500.

- Active Fragment: Interestingly, smaller compounds, specifically the first 34 amino acids adjacent to the N-terminus of the molecule, can also exhibit full PTH activity. This N-terminal fragment is the biologically active portion.

- Metabolism and Measurement: The full-length PTH (84 amino acids) is rapidly cleared by the kidneys. However, the inactive C-terminal fragments of PTH are cleared much more slowly, allowing them to circulate for hours. Therefore, a large share of measured PTH function in clinical assays often reflects these circulating fragments. Measuring intact PTH (1-84) is usually preferred for more accurate assessment of parathyroid function.

Overall Regulatory Role:

PTH primarily regulates ECF calcium and phosphate by acting on:

- Intestinal Reabsorption: Indirectly through its effects on Vitamin D activation.

- Renal Excretion: Directly affecting the reabsorption and secretion of calcium and phosphate in the kidneys.

- Exchange Between ECF and Bone: Directly stimulating bone cells to release or take up calcium and phosphate.

EFFECTS OF PTH ON [CA++] AND [PHOSPHATE] IN ECF

PTH exerts three main effects to increase ECF calcium concentration and generally decrease ECF phosphate concentration:

- Increases Calcium and Phosphate Absorption from the Bone.

- Decreases Calcium Excretion and Increases Phosphate Excretion by the Kidneys.

- Increases Intestinal Absorption of Calcium and Phosphate (indirectly, via Vitamin D activation).

Let's look at each of these in more detail:

1. Increases Calcium and Phosphate Absorption from the Bone

PTH has two phases of action on bone, both leading to the release of calcium and phosphate into the ECF:

- Rapid Phase (Minutes to Hours):

- This phase involves the activation of already existing bone cells, primarily the osteocytes (bone cells embedded within the bone matrix) and potentially osteoblasts (bone-forming cells).

- PTH stimulates these cells to promote the rapid transfer of calcium and phosphate from the bone fluid, which surrounds the bone crystals, into the ECF. This process is thought to involve the osteocytic-osteoblastic pump and increased permeability of the osteocyte membrane.

- Slow Phase (Days to Weeks):

- This phase involves the stimulation of osteoclasts (large cells that resorb bone tissue).

- PTH directly stimulates osteoblasts, which then produce signaling molecules (like RANKL) that activate osteoclasts.

- This leads to the proliferation of osteoclasts and a marked increase in osteoclastic resorption of bone itself, not just absorption from bone fluid. This breaks down the bone matrix, releasing large quantities of calcium and phosphate into the ECF.

2. Decreases Calcium Excretion and Increases Phosphate Excretion by the Kidneys

PTH has opposing effects on calcium and phosphate handling by the kidneys, which is crucial for maintaining their balance:

- Diminishes Proximal Tubular Reabsorption of Phosphate Ions: PTH acts on the renal tubules, particularly the proximal tubule, to decrease the reabsorption of phosphate. This leads to increased phosphate excretion in the urine (phosphaturia), which helps to lower ECF phosphate levels.

- Increases Renal Tubular Reabsorption of Calcium: At the same time that it promotes phosphate excretion, PTH significantly increases the reabsorption of calcium in the renal tubules.

- This increased Ca²⁺ reabsorption occurs mainly in the late distal tubules, the collecting tubules, the early collecting ducts, and possibly the ascending loop of Henle to a lesser extent.

- Importance of Renal Effect: This dual effect on the kidneys is vital. Were it not for the effect of PTH on the kidneys to increase Ca²⁺ reabsorption, the continuous loss of Ca²⁺ into the urine would eventually deplete both the ECF and the bones of this essential mineral, even with PTH's bone-resorbing effects.

3. Increases Intestinal Absorption of Calcium and Phosphate

PTH does not directly act on the intestines. Instead, it exerts this effect indirectly by stimulating the production of active Vitamin D (calcitriol):

- PTH increases the formation in the kidneys of 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol (calcitriol) from inactive Vitamin D precursors.

- As discussed earlier, calcitriol is then responsible for directly increasing the absorption of both calcium and phosphate from the gastrointestinal tract.

ROLE OF CAMP IN PTH ACTIONS

Many of the cellular effects of PTH are mediated by the cyclic AMP (cAMP) second messenger system.

- Mechanism: When PTH binds to its receptors on target cells (e.g., osteocytes, osteoclasts, renal tubular cells), it activates adenylate cyclase, leading to an accumulation of cAMP within the cell.

- Resulting Actions: This increase in intracellular cAMP then triggers a cascade of events that result in:

- Osteoclastic secretion of enzymes and acids to cause bone resorption (as part of the slow phase of bone effect).

- Formation of 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol in the kidneys (activation of 1-alpha-hydroxylase).

- Altered transport mechanisms in the renal tubules leading to increased Ca²⁺ reabsorption and decreased phosphate reabsorption.

- Other Mechanisms: However, it is also believed that other direct effects of PTH on cells may occur independent of cAMP, indicating that PTH signaling can be complex.

CONTROL OF PTH SECRETION BY [CA++]

The secretion of PTH is under an extremely potent and sensitive negative feedback mechanism, directly regulated by the concentration of ionized calcium in the ECF:

- Decrease in ECF [Ca²⁺]: A decrease in ECF [Ca²⁺] is the primary stimulus for increasing PTH production and secretion by the chief cells of the parathyroid glands.

- If this decrease in calcium is prolonged, it can lead to hypertrophy of the parathyroid glands (an increase in their size and cell number) to produce more PTH. This is observed in conditions like rickets (due to chronic low calcium/vitamin D) and also occurs physiologically during pregnancy and lactation, when calcium demands are high.

- Increase in ECF [Ca²⁺]: Conversely, an increase in ECF [Ca²⁺] directly decreases PTH production and secretion.

- If this increase is prolonged, it can lead to atrophy of the parathyroid glands (a decrease in their size and activity). Examples include:

- Excess quantities of calcium in the diet.

- Increased vitamin D in the diet (leading to increased intestinal calcium absorption).

- Bone absorption caused by other factors not involving PTH (e.g., certain bone cancers releasing calcium).

- If this increase is prolonged, it can lead to atrophy of the parathyroid glands (a decrease in their size and activity). Examples include:

This sensitive feedback loop ensures that PTH levels are precisely adjusted to maintain ECF calcium within its narrow physiological range.

CALCITONIN

Calcitonin is a hormone that, in some ways, acts as an antagonist to PTH, primarily by lowering blood calcium levels.

- Chemistry: Calcitonin is a peptide hormone composed of 32 amino acids, with a molecular weight of approximately 3400.

- Source: It is secreted by the Parafollicular cells (C-cells) of the thyroid gland. These C-cells are located in the interstitial fluid (ISF) between the follicles of the thyroid gland.

- Developmental Origin: C-cells constitute a small percentage (about 0.1%) of the thyroid gland and are considered remnants of the ultimobranchial glands of lower animals (such as fish, amphibians, reptiles, and birds), which play a more prominent role in calcium regulation in those species.

- Stimulus for Secretion: Calcitonin is secreted primarily in response to an increase in extracellular fluid (ECF) calcium concentration.

- Effects on Calcium and Phosphate: Calcitonin generally has effects opposite to those of PTH, meaning it tends to decrease ECF calcium levels.

- Decreases Osteoclastic Activity: It primarily acts to inhibit osteoclastic bone resorption, thus preventing the release of calcium and phosphate from bone into the ECF.

- Increases Renal Calcium Excretion: It also slightly increases renal excretion of calcium, though this effect is less pronounced than its action on bone.

- Quantitative Role in Adults: The quantitative role of calcitonin in regulating ECF [Ca²⁺] in healthy adult humans is considered far less significant than that of PTH. Its effects are often weak in adults and are frequently overridden by the more powerful regulatory mechanisms of PTH.

- Significant Effects in Specific Conditions: However, calcitonin can have more potent and clinically relevant effects in certain situations:

- Children: It is more active in children due to their rapid bone remodeling and growth.

- Paget's Disease: It is used therapeutically in conditions like Paget's disease, which is characterized by accelerated and disorganized osteoclastic activity, where calcitonin can help to reduce bone resorption.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF CALCIUM AND PHOSPHATE DISORDERS

The balance of calcium and phosphate can be disrupted by various pathophysiological conditions, primarily involving:

- Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) Abnormalities: Either too much (hyperparathyroidism) or too little (hypoparathyroidism).

- Vitamin D Abnormalities: Deficiency or disorders of its metabolism.

- Bone Diseases: Conditions that directly affect bone structure and metabolism.

HYPOPARATHYROIDISM

Hypoparathyroidism is a condition characterized by insufficient secretion of PTH.

- Etiology: It most commonly results from accidental removal or damage to the parathyroid glands during thyroid surgery.

- Consequences of PTH Deficiency:

- Decreased Bone Resorption: Without sufficient PTH, the osteocytic reabsorption of exchangeable Ca²⁺ decreases, and the osteoclasts become almost totally inactive. As a result, Ca²⁺ and phosphate reabsorption from the bones is severely depressed.

- Hypocalcemia: This leads to a significant decrease in body fluid [Ca²⁺] (hypocalcemia).

- Hyperphosphatemia: The renal tubules fail to excrete phosphate effectively, leading to increased blood phosphate levels (hyperphosphatemia).

- Strong Bones: Paradoxically, in the absence of PTH, bone resorption is minimal, and the bones usually remain strong, often denser than normal, as calcium and phosphate are not being adequately mobilized.

- Clinical Manifestations:

- Rapid Calcium Drop: Following removal of the parathyroid glands, ECF [Ca²⁺] can fall rapidly from the normal 9.4 mg/dL to 6-7 mg/dL within 2 to 3 days.

- Blood Phosphate Doubles: Concurrently, blood phosphate levels can double due to decreased renal excretion.

- Tetany: At calcium levels of 6-7 mg/dL, the characteristic signs of tetany begin to develop due to increased neuromuscular excitability. This is particularly dangerous if it affects the laryngeal muscles, causing spasm and potentially obstructing respiration, which can lead to death.

Treatment of Hypoparathyroidism:

- PTH Administration: While PTH can be administered, it is not usually the primary long-term treatment due to its high cost, short half-life, and potential for immune reactions.

- Vitamin D and Calcium Supplementation (Primary Treatment): The most common and effective treatment involves:

- Large Quantities of Vitamin D: Administering high doses of Vitamin D (e.g., 100,000 units per day) to stimulate intestinal calcium absorption.

- Oral Calcium Intake: Augmenting this with high oral intake of calcium (e.g., 1 to 2 grams per day). This combination helps to keep ECF [Ca²⁺] within the normal range.

- 1,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol (Calcitriol): Sometimes, 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol (the active form of Vitamin D) is administered. It is much more potent and acts faster. However, its high potency can make it difficult to control, leading to potential hypercalcemia if not carefully monitored.

PRIMARY HYPERPARATHYROIDISM

Primary hyperparathyroidism results from an abnormality of the parathyroid glands causing inappropriate and excess PTH secretion.

- Etiology:

- Parathyroid Adenoma: In the vast majority of cases (85-90%), it is caused by a benign tumor (adenoma) of one of the parathyroid glands. Less commonly, it can be due to hyperplasia of all glands or, rarely, carcinoma.

- Gender Predisposition: These tumors occur much more frequently in women than in men or children, possibly due to the increased stress on calcium metabolism during pregnancy and lactation, which can predispose the parathyroid glands to hyperactivity.

- Consequences of Excess PTH:

- Extreme Osteoclastic Activity: The excessive PTH leads to extreme osteoclastic activity in the bones, causing continuous and significant release of calcium and phosphate from bone into the ECF.

- Hypercalcemia: This consistently elevates ECF [Ca²⁺].

- Hypophosphatemia: Simultaneously, the high PTH levels cause increased renal excretion of phosphate, leading to usually depressed concentrations of phosphate ions in the ECF.

Effects of Primary Hyperparathyroidism:

- Bone Disease (Osteitis Fibrosa Cystica):

- In severe hyperparathyroidism, the osteoclastic absorption of bone significantly outstrips osteoblastic deposition. This leads to bone demineralization, fibrous replacement of bone tissue, and the formation of bone cysts, a condition known as osteitis fibrosa cystica. Bones become fragile and prone to fractures.

- Hypercalcemia:

- Plasma calcium levels rise, typically to 12-15 mg/dL, and rarely even higher. The symptoms of hypercalcemia ensue as discussed earlier (depressed nervous system, sluggish reflexes, muscle weakness, constipation, cardiac arrhythmias, polyuria, and polydipsia).

- Metastatic Calcification:

- When extreme quantities of PTH are secreted, ECF [Ca²⁺] rises rapidly to very high values. While PTH normally decreases phosphate, if calcium levels are excessively high, and phosphate levels are not sufficiently decreased (or are increased by other factors), the product of calcium and phosphate concentrations can exceed the solubility constant.

- This leads to supersaturation of CaHPO₄, and crystals of calcium phosphate are deposited in soft tissues throughout the body, a process called metastatic calcification. Common sites include the alveoli of the lungs, renal tubules, thyroid gland, artery walls, and stomach. This can be fatal within days if severe.

- Formation of Kidney Stones (Nephrolithiasis):

- The excess calcium and phosphate absorbed from the intestines (due to PTH-induced Vitamin D activation) or mobilized from the bones leads to significantly increased concentrations of these minerals in the urine.

- This increased urinary concentration, especially of calcium, often results in the precipitation of calcium phosphate or calcium oxalate crystals in the kidney tubules, leading to the formation of kidney stones.

SECONDARY HYPERPARATHYROIDISM

Secondary hyperparathyroidism refers to high levels of PTH that occur as a compensation for chronic hypocalcemia, rather than an intrinsic problem with the parathyroid glands themselves.

- Mechanism: Any condition that consistently lowers ECF [Ca²⁺] will stimulate the parathyroid glands to hypertrophy and secrete more PTH in an attempt to normalize calcium levels.

- Common Causes:

- Vitamin D Deficiency: Insufficient Vitamin D leads to poor intestinal calcium absorption, causing hypocalcemia and stimulating PTH secretion.

- Chronic Renal Disease: Damaged kidneys are unable to produce sufficient amounts of 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol (the active form of Vitamin D) due to impaired 1-alpha-hydroxylase activity. This results in impaired intestinal calcium absorption and hypocalcemia, leading to compensatory PTH elevation. The damaged kidneys also retain phosphate, which further contributes to stimulating PTH secretion.

RICKETS (VITAMIN D DEFICIENCY IN CHILDREN)

Rickets is a bone-softening disease that occurs in children due to a deficiency of Vitamin D, which is essential for proper calcium and phosphate absorption and bone mineralization.

- Etiology: Lack of sufficient Vitamin D, often due to inadequate dietary intake or insufficient exposure to sunlight (UVB radiation needed for skin synthesis).

- Preventive Measure: Adequate exposure to sunlight is crucial for prevention.

- Effects:

- Decreased Plasma Calcium and Phosphate: Vitamin D deficiency leads to impaired intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphate, causing plasma concentrations of both minerals to decrease.

- Weakens Bones: The lower calcium and phosphate levels mean insufficient mineralization of growing bones, leading to soft, weak, and deformed bones.

- Compensatory Secondary Hyperparathyroidism: The hypocalcemia stimulates a compensatory increase in PTH secretion (secondary hyperparathyroidism) which attempts to normalize calcium by resorbing bone, further weakening it, and increasing renal phosphate excretion.

- Tetany: In severe rickets, if ECF [Ca²⁺] falls below 7 mg/dL despite compensatory PTH, tetany can occur.

- Treatment:

- Supplementation: Supplying adequate calcium and phosphate in the diet.

- Vitamin D Administration: Administering large amounts of Vitamin D to restore proper calcium and phosphate absorption and bone mineralization.

ADULT RICKETS (OSTEOMALACIA)

Osteomalacia is the adult equivalent of rickets, characterized by defective bone mineralization leading to soft bones.

- Etiology: Adults seldom have a serious dietary deficiency of Vitamin D or calcium. However, serious deficiencies can occasionally occur, particularly due to:

- Malabsorption Syndromes: Conditions like steatorrhea (failure to absorb fat) are significant causes. Since Vitamin D is fat-soluble, its absorption is impaired in steatorrhea. Additionally, calcium tends to form insoluble soaps with unabsorbed fat in the gut, which are then passed in feces, further exacerbating calcium deficiency.

- Clinical Presentation: Adult rickets (osteomalacia) causes bone pain, muscle weakness, and increased risk of fractures. It typically never proceeds to the stage of tetany in adults as the skeletal system is already mature, and the calcium demands are different compared to growing children. However, it often is a cause of severe bone disability.

RENAL RICKETS

Renal rickets is a type of osteomalacia that results from prolonged kidney damage, often seen in chronic kidney disease.

- Mechanism: The damaged kidneys are unable to perform their critical role in converting 25-hydroxyvitamin D to 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol (the active form of Vitamin D) due to impaired 1-alpha-hydroxylase activity. This leads to Vitamin D deficiency (even if intake is adequate), impaired intestinal calcium absorption, hypocalcemia, and subsequent secondary hyperparathyroidism.

- Severity: This condition is particularly severe in patients undergoing hemodialysis, as their kidney function is severely compromised.

- Vitamin D-Resistant Rickets: Renal rickets can also be caused by congenital hypophosphatemia, which results from congenitally reduced reabsorption of phosphates by the renal tubules. This form of rickets is often referred to as Vitamin D-resistant rickets because it doesn't respond to typical doses of Vitamin D and requires specialized treatment.

OSTEOPOROSIS

Osteoporosis is the most common of all bone diseases in adults, especially prevalent in old age.

- Key Characteristic: It results primarily from diminished organic bone matrix (e.g., collagen, proteoglycans) rather than from poor bone calcification. While the bone that is present is normally mineralized, there is simply less of it.

- Pathophysiology:

- Imbalance in Bone Remodeling: Normally, bone undergoes continuous remodeling, with osteoblastic activity (bone formation) balanced by osteoclastic activity (bone resorption). In osteoporosis, osteoblastic activity is often less than normal, and consequently, the rate of bone osteoid deposition is depressed. This leads to a net loss of bone mass over time.

- Common Causes:

- Lack of Physical Stress on the Bones: Inactivity and a sedentary lifestyle reduce the mechanical stress on bones, which is a critical stimulus for osteoblastic activity and bone formation.

- Malnutrition: Insufficient protein intake means that a sufficient protein matrix (collagen) cannot be formed, which is essential for building new bone.

- Postmenopausal Lack of Estrogen Secretion: Estrogen plays a crucial role in inhibiting osteoclastic activity and promoting bone formation. After menopause, the sharp decline in estrogen levels in women leads to accelerated bone loss, making it a major risk factor for osteoporosis.

- Lack of Vitamin C: Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is essential for collagen synthesis. Deficiency can impair the formation of the organic bone matrix.

- Old Age: With aging, there is a natural decline in osteoblastic activity and an increase in bone resorption, contributing to age-related bone loss.

- Cushing's Syndrome: Excess glucocorticoids (as in Cushing's syndrome or long-term corticosteroid therapy) directly inhibit osteoblast function and promote osteoclast activity, leading to bone loss.

Parathyroid & Calcium Metabolism Quiz

Systems Physiology

Enter your details to begin the examination.

🛡️ Privacy Note: Results are for tracking and certification purposes only.

Parathyroid & Calcium Metabolism Quiz

Systems Physiology

Preparing questions...

Exam Completed!

See your performance breakdown below.