Abdominal Wall Muscles & Hernias

Muscles of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

These muscles provide structural integrity, protect internal organs, enable movements of the trunk, and contribute to vital physiological processes.

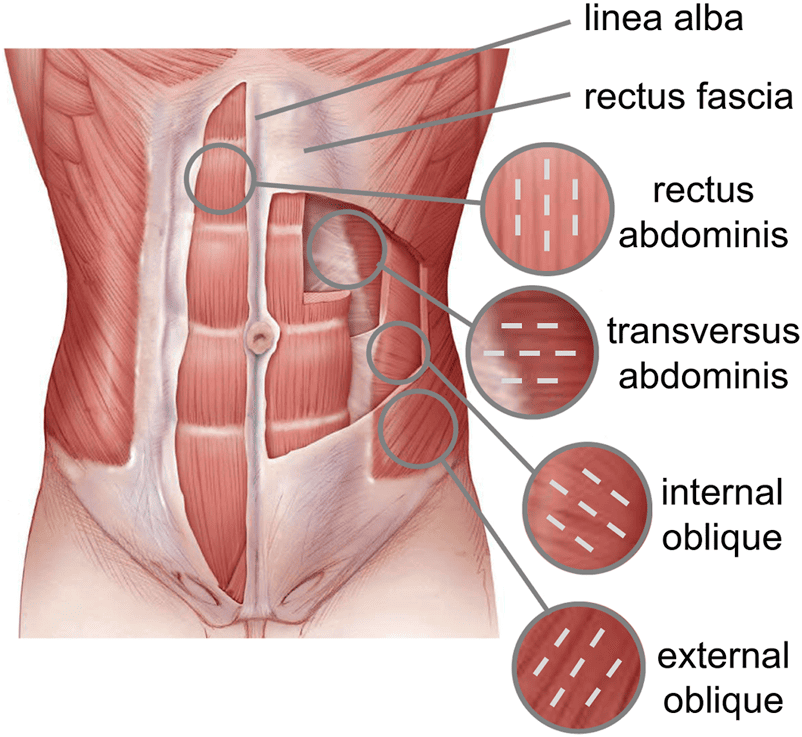

Major Muscles (Flat Muscles and Vertical Muscles):

- External Oblique

- Internal Oblique

- Transversus Abdominis

- Rectus Abdominis

- Pyramidalis (a small, often absent muscle)

1. External Oblique Muscle

Description: The largest and most superficial of the three flat abdominal muscles. Its fibers run inferomedially, similar to placing hands in pockets.

- Origin: External surfaces of the lower eight ribs (ribs 5-12).

- Insertion: Its aponeurosis forms the linea alba, inserts into the pubic crest, pubic tubercle, and the anterior half of the iliac crest. Its thickened inferior border forms the inguinal ligament.

- Nerve Supply: Anterior rami of the lower five thoracic nerves (T7-T11) and the subcostal nerve (T12).

- Action: Unilateral contraction flexes and rotates the trunk to the opposite side. Bilateral contraction flexes the trunk and compresses abdominal contents.

2. Internal Oblique Muscle

Description: Lies deep to the external oblique. Its fibers run superomedially, perpendicular to the external oblique fibers.

- Origin: Thoracolumbar fascia, anterior two-thirds of the iliac crest, and the lateral two-thirds of the inguinal ligament.

- Insertion: Inferior borders of the lower three ribs and their costal cartilages (ribs 10-12), xiphoid process, linea alba, and pubic crest (via conjoint tendon).

- Nerve Supply: Anterior rami of the lower five thoracic nerves (T7-T11), subcostal nerve (T12), iliohypogastric nerve (L1), and ilioinguinal nerve (L1).

- Action: Unilateral contraction flexes and rotates the trunk to the same side. Bilateral contraction flexes the trunk and compresses abdominal contents.

3. Transversus Abdominis Muscle

Description: The deepest of the three flat abdominal muscles. Its fibers run predominantly transversely, hence its name.

- Origin: Internal surfaces of the lower six costal cartilages (ribs 7-12), thoracolumbar fascia, anterior two-thirds of the iliac crest, and the lateral one-third of the inguinal ligament.

- Insertion: Xiphoid process, linea alba, and symphysis pubis (via conjoint tendon).

- Nerve Supply: Anterior rami of the lower five thoracic nerves (T7-T11), subcostal nerve (T12), iliohypogastric nerve (L1), and ilioinguinal nerve (L1).

- Action: Primarily compresses abdominal contents, significantly increasing intra-abdominal pressure. Important for forced expiration, defecation, urination, and childbirth. It also helps stabilize the trunk.

4. Rectus Abdominis Muscle

Description: A pair of long, strap-like vertical muscles that run on either side of the linea alba, extending from the thorax to the pubis.

- Origin: Pubic symphysis and pubic crest.

- Insertion: 5th, 6th, and 7th costal cartilages, and the xiphoid process.

- Features: Characterized by three or more tendinous intersections (lineae transversae) which are firmly attached to the anterior layer of the rectus sheath, giving the "six-pack" appearance.

- Nerve Supply: Anterior rami of the lower six thoracic nerves (T7-T12).

- Action: Powerful flexor of the vertebral column (e.g., sit-ups), compresses abdominal contents, assists in forced expiration.

5. Pyramidalis Muscle

Description: A small, triangular muscle, often not present (absent in about 20% of individuals).

- Origin: Anterior surface of the pubis.

- Insertion: Linea alba, halfway between the umbilicus and pubis.

- Nerve Supply: Subcostal nerve (T12).

- Action: Tenses the linea alba. Clinically, it's a landmark for identifying the midline during lower abdominal incisions.

Blood Supply and Lymphatic Drainage of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

The anterior abdominal wall has a rich and complex vascular network, ensuring ample blood supply to its muscles, fascia, and skin, and efficient lymphatic drainage.

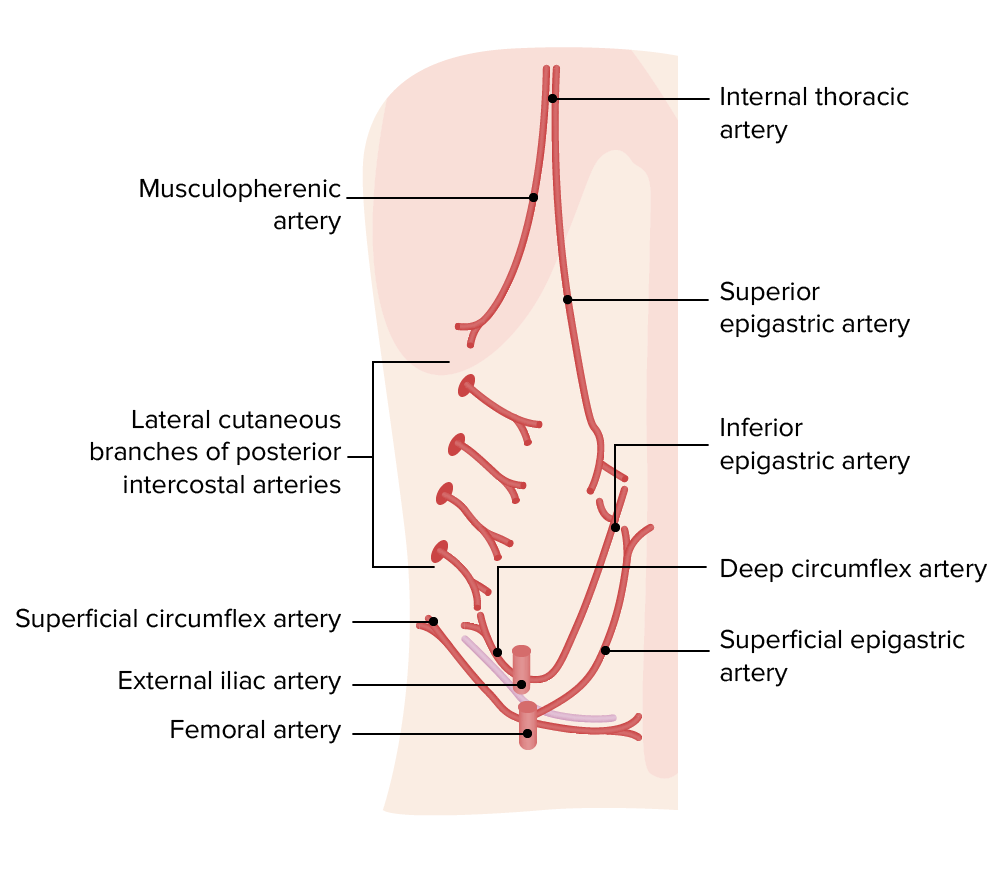

Arterial Supply:

The arterial supply can be broadly categorized based on its origin and location relative to the umbilicus.

- Above the Umbilicus (Superior Supply - primarily from thoracic sources):

- Superior Epigastric Arteries: These are the terminal branches of the internal thoracic arteries. They descend within the rectus sheath, posterior to the rectus abdominis muscle, providing extensive supply to the upper rectus and overlying structures. They anastomose with the inferior epigastric arteries around the umbilical region.

- Posterior Intercostal Arteries (10th and 11th): Branches of the descending aorta that supply the lateral aspects of the upper abdominal wall.

- Subcostal Arteries: The continuation of the 12th intercostal arteries, running inferior to the 12th rib, supplying the lateral lower abdominal wall.

- Musculophrenic Arteries: Branches of the internal thoracic arteries, contributing to the anterolateral supply.

- Lumbar Arteries (1st-4th): Branches of the abdominal aorta, supplying the posterior and lateral abdominal wall, with branches extending anteriorly.

- Below the Umbilicus (Inferior Supply - primarily from femoral and external iliac sources):

- Inferior Epigastric Arteries: These arise from the external iliac artery. They ascend into the rectus sheath, usually entering at the arcuate line, and run superiorly to anastomose with the superior epigastric arteries.

- Branches: Gives off the cremasteric artery (supplies the cremaster muscle and coverings of the spermatic cord in males) and pubic branch.

- Deep Circumflex Iliac Artery: Also a branch of the external iliac artery, runs along the iliac crest, supplying the lateral lower abdominal wall.

- Superficial Epigastric Arteries: Arise from the femoral artery (just below the inguinal ligament), ascend superficially, supplying the skin and superficial fascia of the lower abdominal wall.

- Superficial Circumflex Iliac Arteries: Also arise from the femoral artery, run laterally, supplying the skin and superficial fascia over the iliac crest.

- Superficial External Pudendal Arteries: Arise from the femoral artery, supply the skin and superficial fascia of the lower abdomen and external genitalia.

- Inferior Epigastric Arteries: These arise from the external iliac artery. They ascend into the rectus sheath, usually entering at the arcuate line, and run superiorly to anastomose with the superior epigastric arteries.

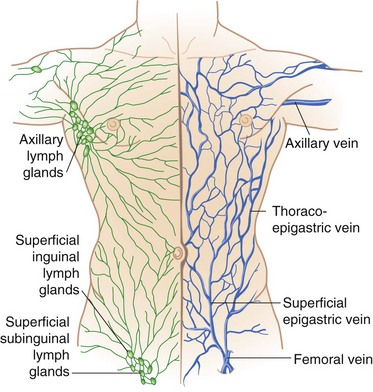

Venous Drainage:

The venous drainage generally mirrors the arterial supply, with superficial veins draining into systemic circulation and deeper veins accompanying the major arteries.

- Superficial Veins: Generally correspond to the superficial arteries.

- Above the Umbilicus: Superficial veins (e.g., tributaries of the superior epigastric veins) drain superiorly towards the axillary veins and brachiocephalic veins (via the internal thoracic/internal mammary veins and eventually the subclavian veins). Indirectly, some drainage can go to the azygos venous system.

- Below the Umbilicus: Superficial veins (e.g., superficial epigastric, superficial circumflex iliac, superficial external pudendal veins) drain inferiorly into the femoral vein (and thence via the great saphenous vein).

- Deep Veins: Accompany the deep arteries.

- Superior Epigastric Vein: Drains into the internal thoracic vein, which then drains into the brachiocephalic vein.

- Inferior Epigastric Vein: Drains into the external iliac vein.

- Deep Circumflex Iliac Vein: Drains into the external iliac vein.

- Lumbar Veins: Drain into the inferior vena cava (IVC).

Lymphatic Drainage:

The lymphatic drainage also follows a distinct pattern based on the umbilical line.

- Above the Umbilicus: Lymph from the skin and superficial fascia drains superiorly into the axillary lymph nodes and the parasternal (sternal) lymph nodes (along the internal thoracic vessels).

- Below the Umbilicus: Lymph from the skin and superficial fascia drains inferiorly into the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

- Deep Lymphatics: Lymph from the muscles and deeper structures generally drains to lymph nodes associated with the major deep vessels (e.g., external iliac nodes, lumbar nodes).

Key Surface Features and Ligaments

These landmarks are essential for both anatomical description and clinical examination.

Linea Alba

Description: The median fibrous raphe extending from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis.

Location: It lies between the paired rectus abdominis muscles.

Formation: It is formed by the fusion of the aponeuroses of the transversus abdominis, internal oblique, and external oblique muscles from both sides. This makes it a strong, yet relatively avascular, midline structure.

Linea Semilunaris

Description: A curved, tendinous intersection that marks the lateral margin of each rectus abdominis muscle.

Location: It typically crosses the costal margin near the tip of the 9th costal cartilage superiorly and extends down to the pubic tubercle.

Inguinal Ligament (Poupart's Ligament)

Description: This is the thickened, inferior rolled-under border of the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle.

Attachments: It stretches from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) laterally to the pubic tubercle medially.

Clinical Significance: It forms the floor of the inguinal canal and is a critical landmark for defining the inguinal region and understanding inguinal hernias.

Rectus Sheath:

The rectus sheath is a crucial fibrous compartment that provides strength and protection to the rectus abdominis muscles.

- Description: It is a strong, tendinous enclosure that surrounds the rectus abdominis muscles (and often the pyramidalis muscle, if present).

- Formation: It is formed by the fusion and interlacing aponeuroses of the three flat abdominal muscles—the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis.

- Layers: It consists of both anterior and posterior laminae (layers) that surround the rectus abdominis muscle. The composition of these layers varies significantly above and below a specific landmark.

Arcuate Line (Linea Arcuata or Douglas' Line):

- Definition: This is a distinct, crescent-shaped line that marks the lower free edge of the posterior lamina of the rectus sheath.

- Location: It typically lies midway between the umbilicus and the pubic symphysis.

- Anatomical Arrangement at the Arcuate Line:

- Above the Arcuate Line:

- Anterior Layer of Rectus Sheath: Formed by the aponeurosis of the external oblique and the anterior lamina (split) of the internal oblique aponeurosis.

- Posterior Layer of Rectus Sheath: Formed by the posterior lamina (split) of the internal oblique aponeurosis and the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis.

- The rectus abdominis muscle is thus sandwiched between these strong anterior and posterior layers.

- Below the Arcuate Line:

- Anterior Layer of Rectus Sheath: Formed by the aponeuroses of all three flat abdominal muscles (external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis), which pass anterior to the rectus abdominis.

- Posterior Layer of Rectus Sheath: The posterior layer is essentially absent. The only structures deep to the rectus abdominis are the transversalis fascia, a variable amount of extraperitoneal fat, and the parietal peritoneum.

- Above the Arcuate Line:

- Clinical Significance: The change in rectus sheath composition at the arcuate line represents an area of relative weakness in the posterior wall of the rectus sheath. This anatomical difference is important in understanding the mechanics of abdominal wall repair and potential sites of hernia formation.

Functions of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

The anterior abdominal wall is a dynamic structure with numerous vital functions.

- Respiration: The abdominal muscles, particularly the transversus abdominis and internal obliques, are essential for forced expiration. By increasing intra-abdominal pressure, they push the diaphragm upwards, expelling air from the lungs.

- Protection: The strong muscular and fascial layers provide a robust protective barrier for the internal abdominal and pelvic organs against external trauma.

- Parturition (Childbirth): During labor, sustained contraction of the abdominal muscles (bearing down or "pushing") significantly increases intra-abdominal pressure, which aids in expelling the fetus from the uterus.

- Urination (Micturition): Contraction of abdominal muscles can assist in increasing intra-abdominal pressure, facilitating the emptying of the urinary bladder, especially during difficult urination.

- Defecation: Similar to urination and parturition, increased intra-abdominal pressure generated by abdominal muscle contraction aids in the expulsion of feces from the rectum.

- Forceful Expiration: Beyond quiet breathing, actions like coughing, sneezing, and blowing involve strong contractions of the abdominal muscles to forcefully expel air.

- Weight Lifting: The abdominal muscles play a crucial role in stabilizing the trunk and spine during lifting heavy objects. They increase intra-abdominal pressure, which acts as a "hydraulic cylinder" to support the lumbar spine, reducing stress on intervertebral discs.

- Thoracoabdominal Pump: The movements of the diaphragm and abdominal wall muscles contribute to a "thoracoabdominal pump" mechanism that aids venous return to the heart and lymphatic flow. Contraction and relaxation cycles create pressure gradients that milk blood and lymph upwards.

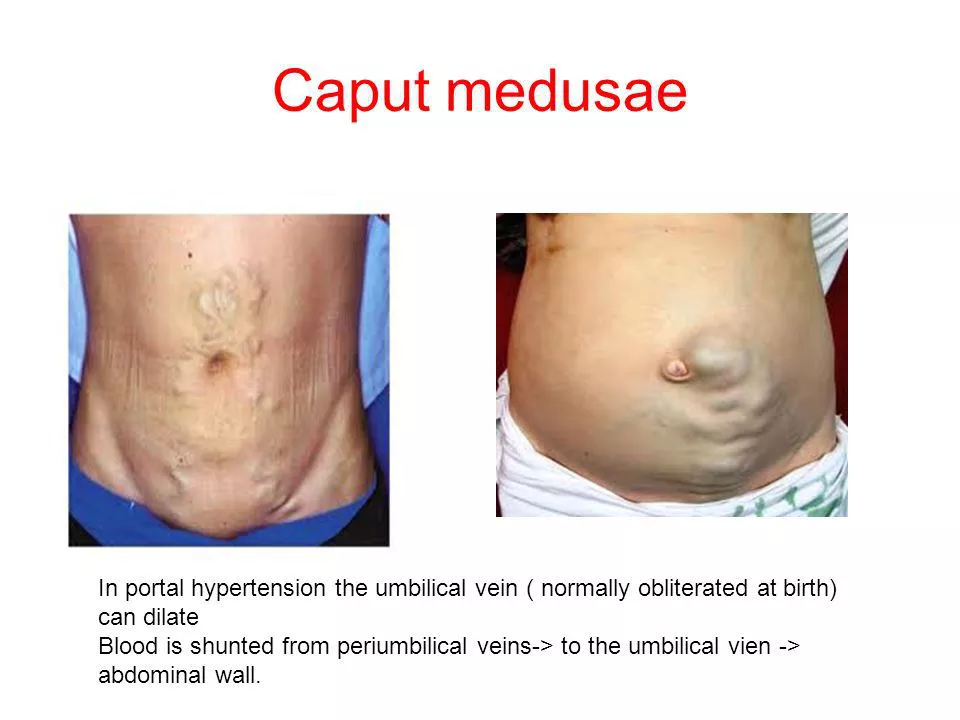

Caput Medusae

This is a distinctive clinical sign that indicates a serious underlying medical condition.

Embryological Context (Umbilical Vein):

In utero, the single umbilical vein (carrying oxygenated blood from the mother to the fetus) connects the placenta to the fetal portal system. After birth, this umbilical vein typically obliterates and becomes the ligamentum teres hepatis. However, recanalized (reopened) remnants of the umbilical vein or surrounding paraumbilical veins can provide a pathway for blood flow in certain pathological states.

Pathophysiology:

- Cause: Caput medusae forms due to the shunting of blood from the liver circulation (specifically, the portal venous system) to the systemic circulation via the veins surrounding the umbilicus.

- Mechanism: This shunting occurs when there is increased pressure within the portal venous system (portal hypertension), typically due to severe liver disease (e.g., cirrhosis, fibrosis) which obstructs or blocks blood flow through the liver via the portal vein.

- Collateral Circulation: The body attempts to bypass this obstruction by opening up or enlarging alternative venous pathways, known as collateral circulation. The paraumbilical veins (which normally carry very little blood) are one such collateral route.

- Distension: Because these paraumbilical veins are not naturally equipped to receive such high volumes of blood at high pressure, they become distended, engorged, and tortuous, forming the characteristic sunburst pattern radiating around the umbilicus.

Clinical Significance: Caput medusae is a definitive sign of severe portal hypertension, commonly associated with advanced liver disease. It indicates a significant impairment of liver function and represents an attempt by the body to decompress the overloaded portal system.

Abdominal Hernia (General Overview)

Definition: A hernia is a protrusion of a viscus (organ) or part of a viscus (e.g., intestine, omentum) through an abnormal opening or a weak point in the wall of the cavity that normally contains it. In the context of abdominal hernias, this refers to the abdominal wall.

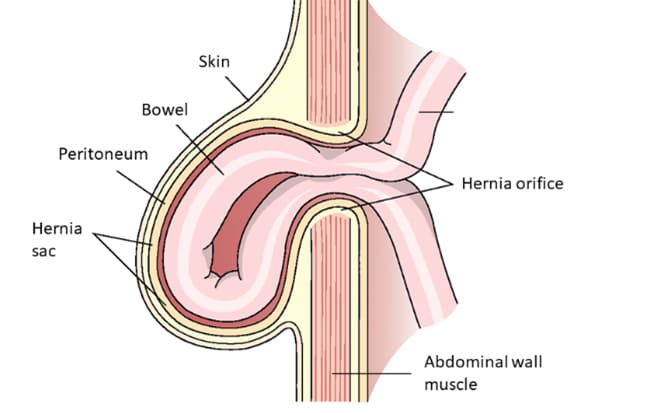

Components of a Hernia:

- Hernial Sac: This is a diverticulum (outpouching) of the peritoneum that forms the container for the protruding contents. It has:

- Neck: The narrow opening of the sac where it exits the abdominal cavity. This is often the site of constriction and potential strangulation.

- Body: The main portion of the sac that contains the herniated contents.

- Fundus: The most distal part of the sac.

- Contents of the Sac: Most commonly, omentum, small intestine, or large intestine. Less commonly, bladder, ovary, or other abdominal organs.

- Coverings of the Sac: Layers of tissue derived from the abdominal wall that surround the peritoneal sac as it pushes through. These layers help determine the specific type of hernia (e.g., indirect vs. direct inguinal hernia).

Etiology (Causes):

- Congenital: Present at birth due to developmental defects or patent structures (e.g., patent processus vaginalis in indirect inguinal hernias, persistent umbilical ring).

- Acquired: Develops later in life due to factors that weaken the abdominal wall or increase intra-abdominal pressure.

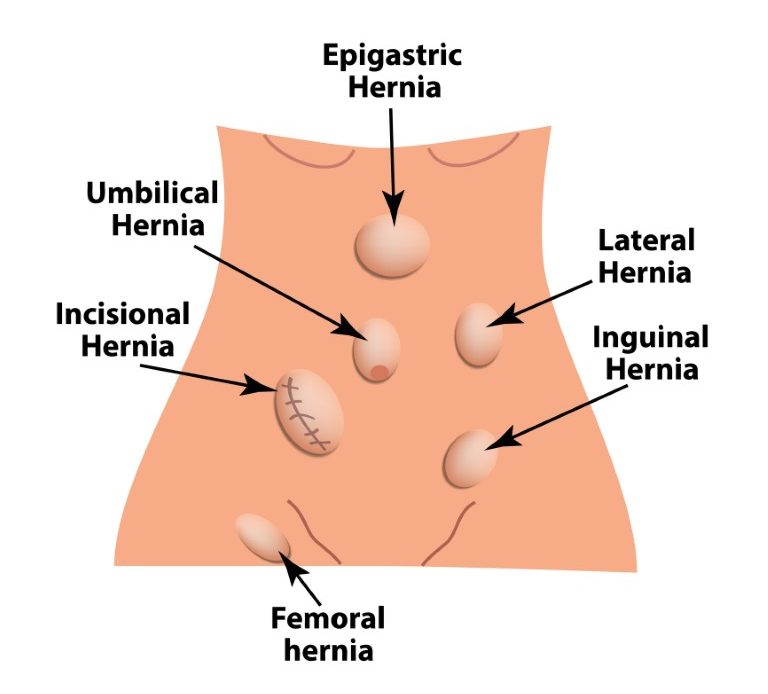

Classification by Location:

- External Hernia: Protrudes through the abdominal wall and is visible or palpable externally (e.g., inguinal, femoral, umbilical).

- Internal Hernia: Protrudes into a peritoneal recess or opening within the abdominal cavity, often not externally visible (e.g., through the foramen of Winslow, paraduodenal hernias).

Clinical Status:

- Reducible: The contents of the hernia sac can be pushed back into the abdominal cavity, either spontaneously or with manual pressure.

- Irreducible (Incarcerated): The contents cannot be returned to the abdominal cavity. This does not necessarily mean strangulation, but it carries a higher risk.

- Strangulated: The blood supply to the herniated contents (especially intestine) is compromised, leading to ischemia, necrosis, and potential perforation. This is a surgical emergency.

- Obstructed: The lumen of the bowel within the hernia sac is blocked, leading to bowel obstruction, but blood supply may still be intact initially.

Types of Herniae (Specific to Abdominal Wall)

1. Inguinal Hernia

General: Occurs in the inguinal region (groin) and is the most common type of abdominal wall hernia, predominantly affecting males.

Anatomical Location: Protrudes through the inguinal canal.

Differentiation from Femoral: The hernia sac is typically above and medial to the pubic tubercle (whereas femoral is below and lateral).

Types of Inguinal Hernia:

- Indirect Inguinal Hernia:

- Etiology: Congenital (though symptoms may present later in life).

- Pathophysiology: Occurs due to the persistence of a patent processus vaginalis. The hernia sac enters the inguinal canal through the deep (internal) inguinal ring.

- Path of Herniation: Follows the course of the spermatic cord.

- Extension: Can extend through the superficial inguinal ring into the scrotum or labia majora.

- Risk: Higher risk of strangulation due to the narrow neck at the deep inguinal ring.

- Direct Inguinal Hernia:

- Etiology: Acquired.

- Pathophysiology: Occurs due to weakening of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, specifically through Hesselbach's triangle.

- Path of Herniation: Pushes directly anteriorly through the posterior wall, exiting via the superficial inguinal ring.

- Risk: Lower risk of strangulation (wider neck). Often appears as a broad-based, non-painful bulge.

2. Femoral Hernia

Location: Occurs in the femoral triangle, specifically through the femoral canal.

Demographics: Predominantly a problem of women, largely due to their wider pelvises.

Characteristics:

- Hernia Sac: Typically small, but can be quite firm.

- Pain: Often very painful.

- Risk of Strangulation: Has a higher tendency of becoming strangulated compared to inguinal hernias due to rigid boundaries.

Differentiation from Inguinal: The hernia sac is located below the inguinal ligament and lateral to the pubic tubercle.

3. Umbilical Herniae

- Congenital Umbilical Hernia (Omphalocele): Failure of physiological retraction of intestinal loops. Bowel remains outside covered by a sac. Often associated with other congenital anomalies.

- Infantile Umbilical Hernia: Incomplete closure of the umbilical ring after birth. Typically small, reducible, often close spontaneously.

- Acquired Umbilical Hernia (Adult): Breakdown/weakening of the umbilical scar. Common in multiparous women, obese individuals, and those with ascites.

4. Epigastric Hernia

Location: Occurs through a defect in the linea alba in the epigastric region (between xiphoid and umbilicus).

Characteristics: Usually small. Contents often omentum or extraperitoneal fat. Can be painful due to nerve irritation.

5. Separation of Rectus Abdominis (Diastasis Recti)

Note: Technically not a true hernia (no fascial defect).

Description: Separation/widening of rectus abdominis muscles along the linea alba.

Etiology: Common in elderly multiparous women, infants, and occasionally men.

Correction: Exercises or surgery (abdominoplasty).

6. Incisional Hernia

Location: At site of previous surgical incision.

Etiology: Failure of surgical wound to heal.

Risk Factors: Nerve damage, poor technique, infection, obesity, malnutrition, chronic cough.

7. Spigelian Hernia

Location: Defect in the spigelian aponeurosis (transversus abdominis aponeurosis) along the linea semilunaris.

Common Site: Usually below the umbilicus.

Characteristics: Sac often expands between muscle layers ("interparietal"), making diagnosis difficult. High risk of strangulation.

8. Lumbar Hernia

Location: Posterior abdominal wall weak points.

Common Sites:

- Petit's Triangle (Inferior Lumbar): Bounded by iliac crest, latissimus dorsi, and external oblique.

- Grynfeltt-Lesshaft Triangle (Superior Lumbar): Less common, more superior.

9. Internal Hernia

Definition: Viscus protrudes into a peritoneal recess or opening within the abdominal cavity, without exiting the wall.

Locations: Paraduodenal, Foramen of Winslow, Transmesenteric, Transomental.

Clinical Challenge: Difficult to diagnose preoperatively. High risk of strangulation/obstruction.

Incisions of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

Surgical incisions are carefully chosen to balance access, healing, cosmetic outcome, and minimization of complications.

1. Vertical Incisions:

- Midline Incision (Epigastric, Midline, or Low Midline):

- Path: Runs vertically along the linea alba.

- Advantages: Almost bloodless, no muscle fibers divided, no nerves injured, excellent access, quick.

- Disadvantages: Prone to dehiscence and incisional hernia.

- Paramedian Incision (Pararectus Incision):

- Path: Placed 2-5 cm lateral to midline. Rectus muscle is retracted.

- Theoretical Advantages: Offsets vertical incision, potentially more secure closure (rectus muscle acts as "buttress").

- Disadvantages: Divides anterior rectus sheath, more painful, risk of nerve injury. Less common today.

2. Transverse Incisions:

Kocher Subcostal Incision

Path: Parallel to and below costal margin.

Advantages: Excellent exposure to gallbladder/biliary tract (right) or spleen (left).

Disadvantages: Cuts muscle/nerve, more painful.

McBurney Incision (Gridiron)

Path: Small oblique incision in RLQ at McBurney's point. Muscles split (gridiron).

Use: Classic for appendectomy.

Advantages: Minimally invasive, preserves nerve/muscle, low hernia rate.

Pfannenstiel Incision

Path: Curved transverse in suprapubic region ("bikini line").

Use: Gynecological/Obstetric procedures (C-sections, hysterectomies).

Advantages: Excellent cosmesis, strong closure, less painful.

Rutherford-Morison (Hockey-stick)

Path: Curved in RUQ.

Use: Primarily for kidney access.

Double Kocher's (Rooftop/Chevron)

Path: Two Kocher incisions joined in midline (inverted "V").

Use: Wide exposure to upper abdomen (liver transplant, gastrectomy).

Abdominal Muscles & Hernias Quiz

Systems Anatomy

Enter your details to begin the examination.

🛡️ Privacy Note: Results are for tracking and certification purposes only.

Abdominal Muscles & Hernias Quiz

Systems Anatomy

Preparing questions...

Exam Completed!

See your performance breakdown below.