Lower Respiratory Anatomy

Lower Respiratory Tract Overview

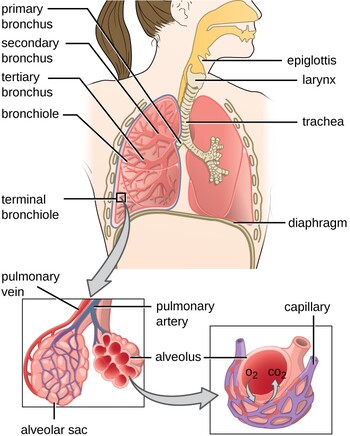

The lower respiratory tract is responsible for conducting air deep into the lungs and for the vital process of gas exchange. It begins immediately inferior to the larynx.

- Components: It consists of the trachea, the main bronchi (primary, secondary, tertiary), progressively smaller bronchioles, and ultimately the microscopic alveolar sacs (which contain alveoli).

- Functional Unit: The lungs are the primary organs of respiration, formed by the branching bronchial tree culminating in the respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveolar sacs, all encased within pleural membranes. The statement "Bronchioles and alveolar sacs collectively form lungs" is an oversimplification; the lungs also include the larger bronchi, blood vessels, nerves, lymphatic tissue, and connective tissue.

- Functions:

- Air Conduction: Transporting inhaled air from the upper respiratory tract to the alveoli, and exhaled air in the opposite direction.

- Respiration (Gas Exchange): Facilitating the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the air in the alveoli and the blood in the pulmonary capillaries.

Trachea

The trachea, or windpipe, is a crucial component of the lower respiratory tract, providing a patent pathway for air to and from the lungs.

- Structure: It is a mobile, flexible fibrocartilaginous and membranous tube.

- Origin: It begins in the neck as a direct continuation of the larynx, specifically at the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage, typically at the level of the C6 vertebra.

- Course: It descends anterior to the esophagus, initially in the midline of the neck, and then slightly deviates in the thorax.

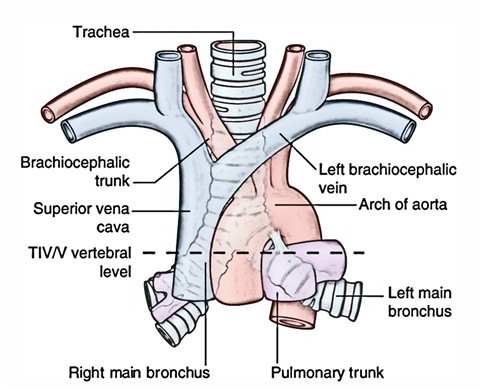

- Termination: The trachea terminates in the thorax by bifurcating into the right and left main (principal) bronchi. This bifurcation point is known as the carina.

- Anatomical Landmark: The carina is located approximately at the level of the sternal angle anteriorly, and between the T4 and T5 vertebral bodies posteriorly.

Structure of the Trachea

The unique structure of the trachea is adapted for its function of maintaining an open airway while allowing some flexibility.

- Cartilaginous Support: The trachea is supported by 16-20 C-shaped (incomplete) cartilaginous rings, primarily composed of hyaline cartilage. These rings are crucial for keeping the tracheal lumen continuously patent, preventing collapse during inspiration or changes in neck position.

- Posterior Deficiency: The tracheal rings are deficient posteriorly. This allows the trachea to flatten slightly against the esophagus during swallowing, facilitating the passage of food.

- Trachealis Muscle: The posterior, open ends of the C-shaped cartilages are connected by the trachealis muscle, a band of smooth muscle.

- Function: Contraction of the trachealis muscle can narrow the tracheal lumen, which is important during coughing to increase the velocity of air expulsion, aiding in clearing mucus and foreign material.

- Shape of Lumen: Due to the posterior trachealis muscle, the trachea's lumen is not perfectly circular but rather slightly D-shaped or flattened posteriorly. The statement "the posterior wall of the trachea is flat" accurately describes this.

- Dimensions:

- Adults: The average diameter of the trachea in adults is about 2.5 cm (1 inch). The length is typically 10-12 cm.

- Infants: In infants, the tracheal diameter is much smaller, roughly equivalent to the diameter of a pencil (or the child's little finger), making them more susceptible to airway obstruction.

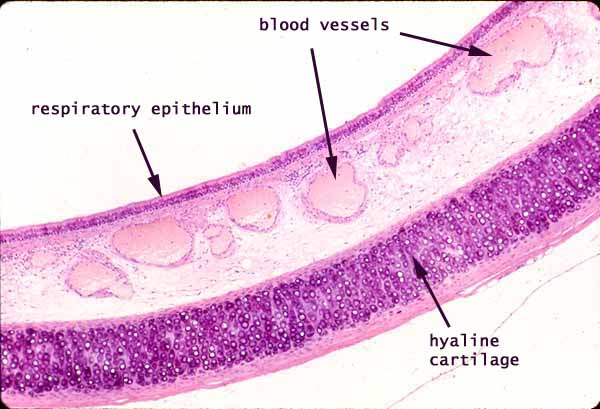

Histology of the Trachea

The tracheal wall is composed of several layers, each contributing to its function:

- Mucosa:

- Epithelium: Lined by pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium with abundant goblet cells. This is characteristic respiratory epithelium.

- Cilia: Beat synchronously to propel mucus and trapped particles upwards, towards the pharynx.

- Goblet Cells: Produce mucus, which traps inhaled dust, pollen, and microorganisms.

- Lamina Propria: A layer of loose connective tissue rich in elastic fibers, lymphoid cells, and mucous glands.

- Epithelium: Lined by pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium with abundant goblet cells. This is characteristic respiratory epithelium.

- Submucosa: Contains seromucous glands (tubular mucous glands in the original description) that supplement the mucus produced by goblet cells, along with blood vessels and nerves.

- Cartilaginous Layer: Composed of the C-shaped hyaline cartilage rings.

- Adventitia: The outermost layer of connective tissue, blending with surrounding tissues.

- Function: The mucociliary escalator system (ciliated epithelium + mucus) is a critical defense mechanism, continuously trapping and moving inhaled foreign particles and pathogens out of the lower respiratory tract, preventing them from reaching the delicate alveoli.

Relations of the Trachea

Understanding the anatomical relations of the trachea is vital, especially in surgical procedures involving the neck and mediastinum.

A. Cervical Trachea (in the Neck)

Anteriorly:

- Skin, superficial fascia, deep cervical fascia (investing layer).

- Infrahyoid Muscles: Sternohyoid and sternothyroid muscles.

- Thyroid Gland Isthmus: Typically lies anterior to the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th tracheal rings.

- Vascular Structures: Inferior thyroid veins (form a plexus), jugular venous arch, and sometimes the thyroidea ima artery (an anomalous artery arising from the brachiocephalic trunk or aorta).

- In Children: The left brachiocephalic vein (innominate vein) is higher and may be more anteriorly related to the trachea.

Posteriorly:

- Esophagus: The trachea is always anterior to the esophagus.

- Recurrent Laryngeal Nerves: These nerves ascend in the tracheoesophageal grooves on either side.

Laterally:

- Thyroid Gland Lobes: The lateral lobes of the thyroid gland lie on either side of the trachea.

- Carotid Sheath Contents: Common carotid artery, internal jugular vein, and vagus nerve are located lateral to the trachea, within their respective carotid sheaths.

B. Thoracic Trachea (in the Thorax)

- Anteriorly:

- Manubrium of Sternum.

- Thymus: In children, the thymus gland is prominent.

- Major Vessels: Arch of aorta (initially to the left, then over the trachea), brachiocephalic trunk, left common carotid artery, left subclavian artery, left brachiocephalic vein.

- Posteriorly:

- Esophagus: Continues its posterior relation.

- Right Side:

- Right vagus nerve, azygos vein, right pleura.

- Left Side:

- Arch of aorta, left common carotid artery, left subclavian artery, left vagus nerve, left recurrent laryngeal nerve, left pleura.

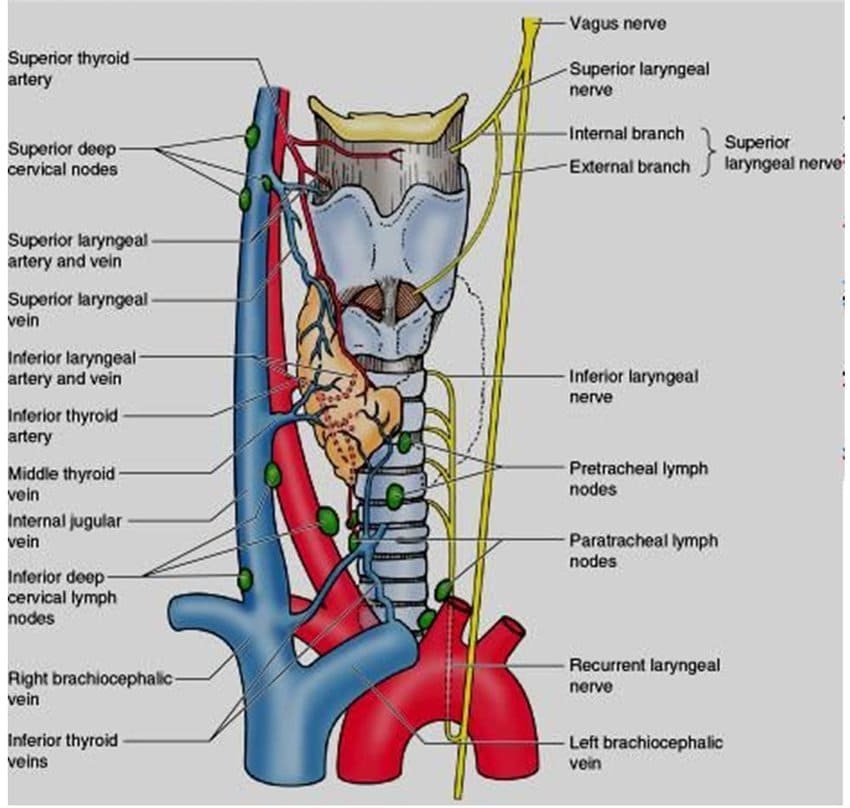

Neurovascular Supply & Lymph Drainage of the Trachea

A. Nerve Supply

- Sensory Innervation: Primarily supplied by branches of the vagus nerves (CN X) and the recurrent laryngeal nerves. These nerves convey sensory information (e.g., irritation, cough reflex) from the tracheal mucosa.

- Autonomic Innervation:

- Parasympathetic (Vagus/Recurrent Laryngeal): Stimulates tracheal gland secretion and smooth muscle contraction (trachealis muscle).

- Sympathetic (Sympathetic Trunks): Causes bronchodilation and inhibits glandular secretion (less significant in trachea than bronchioles).

B. Blood Supply

- Arterial Supply: The trachea receives its blood supply from a segmental arrangement of arteries.

- Upper Two-Thirds: Primarily supplied by tracheal branches from the inferior thyroid arteries.

- Lower One-Third (Thoracic Trachea): Primarily supplied by branches from the bronchial arteries (which typically arise from the thoracic aorta).

- Venous Drainage: Tracheal veins drain into the inferior thyroid veins and the azygos, hemiazygos, or accessory hemiazygos veins.

C. Lymph Drainage

- Lymph from the trachea drains into regional lymph nodes:

- Prelaryngeal and Pretracheal Lymph Nodes: Located anterior to the larynx and trachea.

- Paratracheal Lymph Nodes: Located alongside the trachea.

- Ultimately, these drain into the deep cervical lymph nodes and potentially the bronchopulmonary lymph nodes.

III. Clinical Correlates of the Trachea

Several clinical conditions relate directly to the anatomy and function of the trachea.

- Tracheal Deviation: Deviation of the trachea from its normal midline position is a critical clinical sign, often indicative of significant intrathoracic pathology.

- Causes:

- Pushed Away (Contralateral Shift): Tension pneumothorax (air accumulation pushing structures away), large pleural effusion (fluid), large neck mass or thyroid goiter.

- Pulled Towards (Ipsilateral Shift): Atelectasis (collapsed lung), pulmonary fibrosis (scarring), pneumonectomy (surgical removal of a lung).

- Causes:

- Tracheal Trauma:

- Vulnerability: Due to its relatively superficial position in the neck and its close proximity to the esophagus, the trachea can be susceptible to trauma (e.g., blunt neck trauma, penetrating injuries).

- Esophageal Involvement: Tracheal injuries often involve or are associated with esophageal injury, leading to tracheoesophageal fistulas.

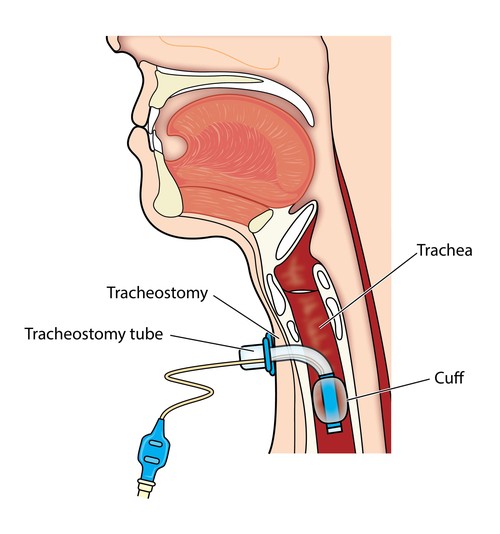

- Tracheostomy: A surgical procedure to create a temporary or permanent opening (tracheostoma) in the anterior wall of the trachea, typically below the cricoid cartilage (usually through the 2nd-4th tracheal rings), and inserting a tracheostomy tube.

- Indications:

- Upper Airway Obstruction: To bypass an obstruction in the upper airway (e.g., severe laryngeal edema, laryngeal cancer, severe trauma to the larynx/pharynx).

- Respiratory Failure: To facilitate long-term mechanical ventilation, allowing easier access for suctioning and reducing the risk of laryngeal injury from prolonged endotracheal intubation.

- Protection of Lower Airway: To prevent aspiration in patients with severe swallowing dysfunction.

- Risks & Complications: Hemorrhage, infection, pneumothorax, tracheal stenosis, tracheoesophageal fistula.

- Indications:

- Tracheal Stenosis: Narrowing of the tracheal lumen, often a complication of prolonged intubation or tracheostomy, or due to trauma, infection, or tumors.

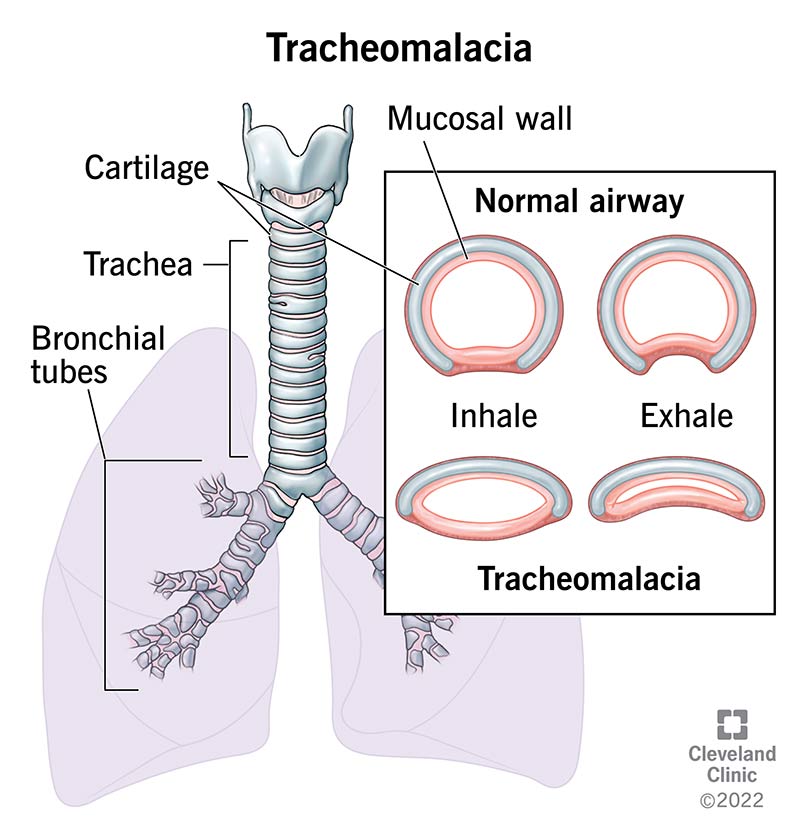

- Tracheomalacia: Weakness of the tracheal cartilages, leading to dynamic collapse of the trachea, particularly during expiration. More common in children.

Tracheostomy

Tracheostomy is a surgical procedure to create a temporary or permanent opening (tracheostoma) through the anterior neck into the trachea, allowing for direct access to the lower respiratory tract. It is distinct from cricothyrotomy, which is an emergency procedure performed through the cricothyroid membrane.

A. Indications

Tracheostomy is performed for various reasons, including:

- Upper Airway Obstruction: To bypass an obstruction above the trachea (e.g., severe edema, tumor, foreign body, laryngeal trauma, bilateral vocal cord paralysis).

- Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation: To facilitate long-term ventilation, reduce airway resistance, and improve patient comfort compared to prolonged endotracheal intubation.

- Pulmonary Hygiene: To allow for easier removal of tracheobronchial secretions in patients with impaired cough reflexes.

- Airway Protection: To prevent aspiration in patients with severe dysphagia or impaired airway protective reflexes.

B. Procedure Overview (Surgical Tracheostomy)

- Patient Positioning: The patient's neck is extended (hyperextended) to bring the trachea into a more superficial position and lengthen the neck. A shoulder roll can aid this.

- Anatomical Landmarks: The thyroid cartilage (Adam's apple) and the cricoid cartilage (the only complete ring below the thyroid) are carefully identified by palpation.

- Skin Incision:

- A vertical skin incision is often made in the midline from below the cricoid cartilage towards the suprasternal notch. (A horizontal "collar" incision can also be used for better cosmetic results, typically 2 cm below the cricoid).

- The incision proceeds through the skin, superficial fascia, and platysma muscle. Careful attention is paid to avoid the anterior jugular veins, which typically run vertically, one on each side of the midline.

- Deep Dissection:

- The investing layer of deep cervical fascia is incised in the midline.

- The strap muscles (sternohyoid and sternothyroid) are identified and typically separated in the midline or retracted laterally.

- The pretracheal fascia is then incised, revealing the trachea.

- Thyroid Isthmus Management: The isthmus of the thyroid gland, which usually overlies the 2nd to 4th tracheal rings, is identified. Depending on its size and position, it may need to be:

- Retracted superiorly or inferiorly.

- Divided and ligated (transected) in the midline if it significantly obstructs access.

- Tracheal Incision:

- The tracheal rings are palpated.

- The trachea is entered, preferably through the second or third tracheal ring (sometimes the fourth), in the midline. The first tracheal ring is generally avoided to prevent damage to the cricoid cartilage and potential subglottic stenosis.

- Various types of tracheal incisions can be made (e.g., horizontal, vertical, H-shaped, U-shaped flap).

- Tracheostomy Tube Insertion: A tracheostomy tube of appropriate size is inserted into the tracheal opening.

- Securing the Tube: The tube is secured, and its position is confirmed.

C. Complications of Tracheostomy

Tracheostomy, while life-saving, carries several potential complications, both immediate and long-term:

- Hemorrhage:

- Intraoperative/Early: Can occur from injury to highly vascular structures like the thyroid gland isthmus, anterior jugular veins, inferior thyroid veins, or a high-riding thyroidea ima artery.

- Late: Tracheo-innominate fistula (erosion into the brachiocephalic artery) is a rare but catastrophic complication.

- Nerve Paralysis (Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Injury):

- The recurrent laryngeal nerves ascend in the tracheoesophageal grooves. While less common than with thyroid surgery, direct trauma, thermal injury, or excessive traction during dissection can damage these nerves.

- Effect: Leads to vocal cord paralysis, causing hoarseness or, if bilateral, severe airway compromise.

- Pneumothorax:

- Mechanism: Injury to the pleural apex (cervical dome of pleura), which extends into the neck, can occur if dissection is too deep or lateral, particularly in infants where the pleura is higher.

- Effect: Air enters the pleural space, leading to lung collapse.

- Esophageal Injury (Perforation):

- Mechanism: The esophagus lies directly posterior to the trachea. Deep or uncontrolled incision, especially with a sharp instrument, can perforate the esophagus.

- Risk Factors: Increased risk in infants due to smaller anatomical dimensions and in patients with distorted anatomy.

- Subcutaneous Emphysema: Air tracking into the tissues of the neck and chest, usually due to a tight skin incision or tube displacement.

- Tracheal Stenosis: Narrowing of the trachea, often at the stoma site or cuff site, due to granulation tissue formation, scar contracture, or prolonged pressure from the tube.

- Tracheomalacia: Weakening of the tracheal wall, leading to collapse, often due to prolonged pressure from an overinflated cuff.

- Decannulation Complications: Difficulty removing the tracheostomy tube due to airway obstruction above the stoma, or persistent tracheocutaneous fistula (opening that fails to close).

- Infection: Stoma site infection, tracheitis, or pneumonia.

- Tube Displacement or Obstruction: Accidental decannulation (tube coming out) or blockage of the tube by mucus plugs.

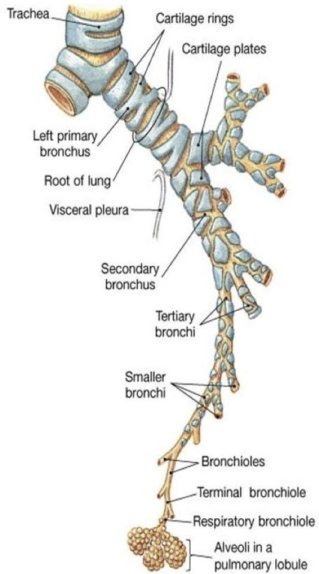

I. Bronchial Tree

The bronchial tree is the elaborate network of progressively smaller airways that branch from the trachea and conduct air into and out of the lungs.

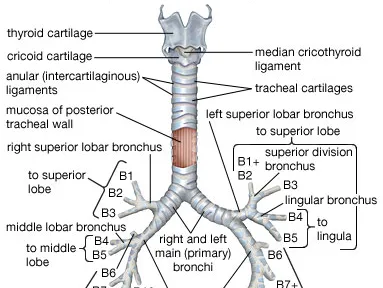

Main Bronchi (Primary Bronchi):

- The trachea bifurcates at the carina (level of sternal angle, T4-T5) into the right and left main (primary) bronchi.

- Right Main Bronchus:

- Characteristics: It is wider, shorter, and more vertical than the left. This anatomical configuration makes it the most common site for aspirated foreign bodies to lodge.

- Branching: It gives off three lobar (secondary) bronchi for the three lobes of the right lung. The right upper lobar bronchus typically branches off before the main bronchus enters the hilum.

Left Main Bronchus:

- Characteristics: It is longer, narrower, and less vertical (more acutely angled) than the right, traversing inferior to the arch of the aorta.

- Branching: It gives off two lobar (secondary) bronchi for the two lobes of the left lung. The superior and lingular bronchi on the left are often referred to as the "upper division" and "lingular division" of the left upper lobar bronchus, respectively, reflecting their common origin before separating. The original statement "the upper two are fused for a short distance before separating into the upper lobe and the lingular lobe bronchus" accurately describes this.

Segmental Bronchi and Bronchopulmonary Segments

Beyond the lobar bronchi, the airway further subdivides into segmental (tertiary) bronchi, each supplying a specific region of the lung known as a bronchopulmonary segment.

Bronchopulmonary Segments:

- These are the largest subdivisions of a lung lobe.

- Each segment is an independent, functionally and anatomically discrete respiratory unit, supplied by its own segmental bronchus and tertiary branch of the pulmonary artery.

- They are roughly pyramidal in shape, with their apices pointing towards the hilum of the lung and their bases lying on the pleural surface.

- They are separated from adjacent segments by connective tissue septa. This anatomical arrangement allows for the surgical removal of a diseased segment without significantly affecting surrounding segments.

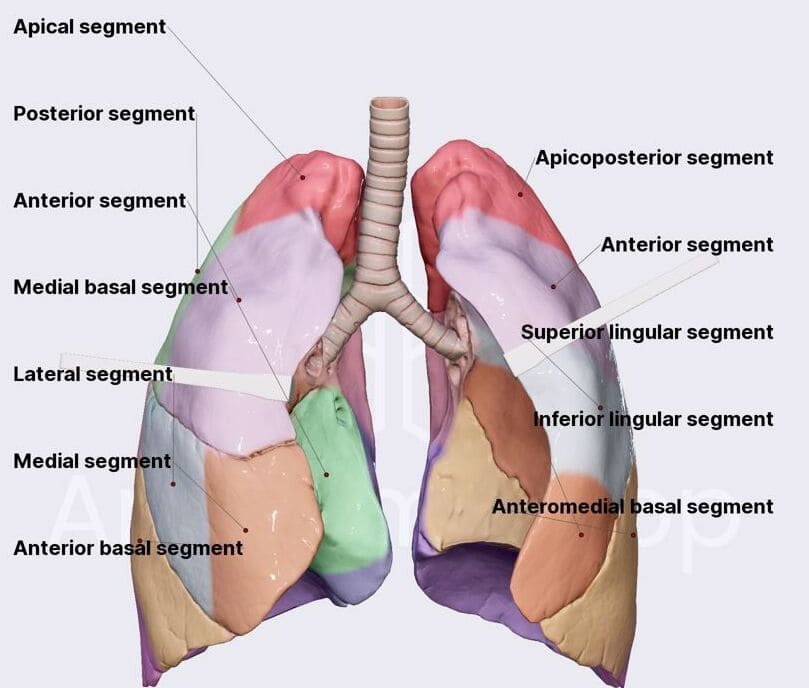

Number and Naming of Segmental Bronchi (and the segments they supply):

Right Lung (3 Lobes, 10 Segments):

- Right Upper Lobe (3 segments):

- a. Apical

- b. Posterior

- c. Anterior

- Right Middle Lobe (2 segments):

- a. Lateral

- b. Medial

- Right Lower Lobe (5 segments):

- a. Superior (Apical)

- b. Medial Basal

- c. Anterior Basal

- d. Lateral Basal

- e. Posterior Basal

Left Lung (2 Lobes, typically 8-10 segments, often described as 8 due to fusions):

- Left Upper Lobe (typically 4 segments, including the lingula):

- a. Upper Division:

- i. Apical-Posterior (often fused)

- ii. Anterior

- b. Lingular Division:

- i. Superior Lingular

- ii. Inferior Lingular

- a. Upper Division:

- Left Lower Lobe (typically 4-5 segments):

- a. Superior (Apical)

- b. Anteromedial Basal (often fused)

- c. Lateral Basal

- d. Posterior Basal

Note on Left Lung: The left lung generally mirrors the right, but the apical and posterior segments of the upper lobe are often fused (Apico-Posterior), and the medial basal segment of the lower lobe is often fused with the anterior basal segment (Antero-Medial Basal). The lingula is considered homologous to the middle lobe of the right lung.

II. Lungs

The lungs are the primary organs of respiration, located in the thoracic cavity, where they facilitate gas exchange.

Gross Appearance:

- Color: In healthy infants, they are pink. In adults, due to inhaled particulate matter, they appear mottled gray-pink.

- Texture: They are soft, spongy, and crepitant (crackling sensation due to trapped air) to the touch when healthy and aerated.

Shape and Conformity:

Each lung is conical in shape, conforming to the contours of the thoracic cavity.

- Apex: Rounded superior end, extending into the root of the neck, projecting about 2.5 cm (1 inch) above the clavicle. This makes the apex vulnerable to injury during supraclavicular procedures.

- Base: Concave, resting on the convex dome of the diaphragm.

- Surfaces:

- Costal Surface: Large, convex, facing the ribs and intercostal spaces.

- Diaphragmatic Surface: Concave, forming the base of the lung.

- Mediastinal Surface: Concave, facing the mediastinum and containing the hilum.

- Borders:

- Anterior Border: Thin and sharp.

- Posterior Border: Thick and rounded, fitting into the paravertebral gutters (grooves on either side of the vertebral column).

- Inferior Border: Sharp.

Impressions and Grooves:

- Cardiac Impression:

- Left Lung: Features a deep indentation called the cardiac notch (or incisura cardiaca) on its anterior border, accommodating the heart. Inferior to the cardiac notch is the lingula, a tongue-like projection.

- Right Lung: Has a much shallower cardiac impression on its mediastinal surface.

- Vascular Grooves:

- Right Lung: A prominent groove for the arch of the azygos vein curves superiorly over the root of the right lung.

- Apical Grooves: The apices of both lungs are grooved by the subclavian arteries as they pass superior to the first rib.

- Other Impressions: Impressions for the aorta, esophagus, SVC, IVC, etc., are also present on the mediastinal surfaces, depending on the lung.

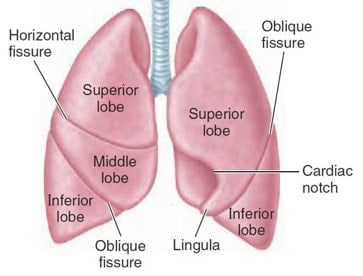

Fissures of the Lungs

The lungs are divided into lobes by deep invaginations of the visceral pleura called fissures.

A. Oblique Fissure (Major Fissure)

- Presence: Found in both the right and left lungs.

- Course: Extends from the costal surface, typically beginning around the T3 vertebra posteriorly, running obliquely downwards and forwards to reach the 6th costochondral junction anteriorly.

- Division:

- Right Lung: Separates the middle lobe from the lower lobe, and the upper lobe from the lower lobe.

- Left Lung: Separates the upper lobe from the lower lobe.

- Completeness: The oblique fissure usually extends from the surface to the hilum, functionally separating the lobes, though they remain connected by the bronchi and pulmonary vessels at the hilum.

B. Horizontal Fissure (Minor Fissure)

- Presence: Found only in the right lung.

- Course: Extends horizontally from the anterior border, usually at the level of the 4th costal cartilage, to meet the oblique fissure.

- Division: Separates the upper lobe from the middle lobe.

- Completeness: The horizontal fissure is notorious for its anatomical variability. As noted in the original text, it is completely separated from the upper lobe in only about one-third of individuals. In the remainder, the separation can be incomplete to varying degrees, which has surgical implications.

C. Lobes and Segments

- Lobes:

- Right Lung: Three lobes (upper, middle, lower).

- Left Lung: Two lobes (upper, lower), with the lingula being a functional subdivision of the upper lobe.

- Segments: Each lobe is further subdivided into bronchopulmonary segments, as previously discussed. While the concept of segments is similar on both sides (each having its own bronchus and artery), the precise pattern of bronchial branching and the naming of segments differs between the right and left lungs.

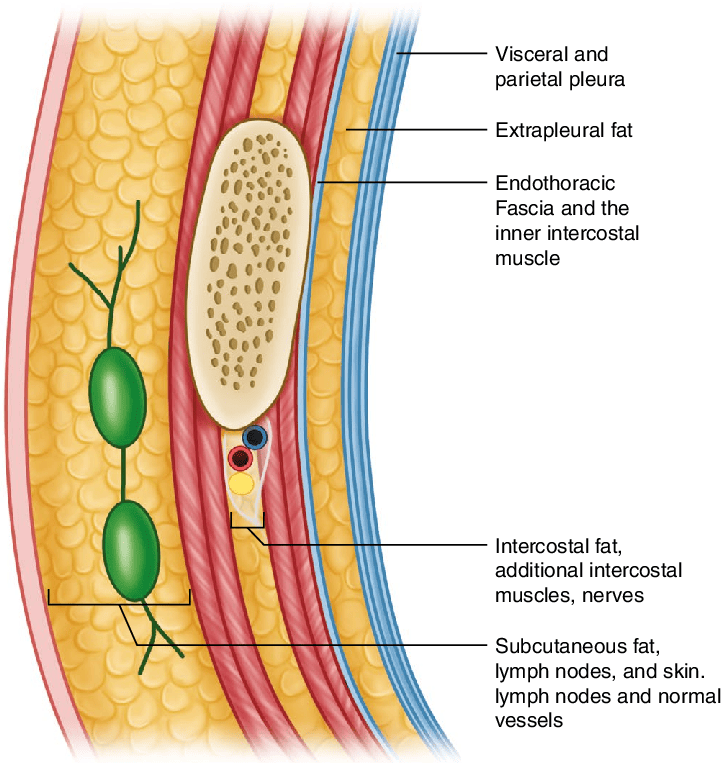

III. Pleura

The pleura is a serous membrane that envelops the lungs and lines the walls of the thoracic cavity, providing a smooth, frictionless surface for lung movement.

- Structure: It consists of a single layer of flattened mesothelial cells resting on a thin layer of connective (fibrous) tissue.

- Layers: The pleura has two main continuous layers:

- Visceral Pleura:

- Coverage: Directly covers the entire surface of the lung, adhering tightly to it. It dips into and lines the depths of all the interlobar fissures.

- Mobility: Cannot be dissected from the lung.

- Parietal Pleura:

- Coverage: Lines the inner surface of the thoracic wall, mediastinum, and diaphragm. It is named according to the region it covers:

- Costal Pleura: Lines the inner surface of the ribs and intercostal spaces.

- Diaphragmatic Pleura: Covers the superior (thoracic) surface of the diaphragm.

- Mediastinal Pleura: Covers the lateral aspects of the mediastinum (e.g., pericardium, great vessels).

- Cervical Pleura (Cupula Pleurae): Extends superiorly through the thoracic inlet into the neck, overlying the apex of the lung. It is reinforced by the suprapleural membrane (Sibson's fascia).

- Attachment: Attached to the thoracic wall by loose connective tissue known as the endothoracic fascia.

- Coverage: Lines the inner surface of the thoracic wall, mediastinum, and diaphragm. It is named according to the region it covers:

- Visceral Pleura:

- Pleural Cavity:

- The pleural cavity is the potential space between the visceral and parietal layers of the pleura.

- It is a completely closed space (in health) and contains a thin film of pleural fluid.

- Function of Pleura and Pleural Fluid:

- Frictionless Movement: The thin film of pleural fluid acts as a lubricant, allowing the two pleural layers to slide smoothly over each other during respiration, minimizing friction between the mobile lungs and the stationary thoracic wall.

- Surface Tension: The surface tension of the pleural fluid causes the visceral and parietal pleura to adhere to each other, ensuring that the lungs expand and recoil with the thoracic cage.

- Pleural Recesses: The parietal pleura extends beyond the confines of the lung, creating potential spaces called pleural recesses where the lungs expand during deep inspiration. The most significant are:

- Costodiaphragmatic Recesses: Between the costal and diaphragmatic pleura.

- Costomediastinal Recesses: Between the costal and mediastinal pleura.

- Pulmonary Ligament: At the hilum, where the visceral and parietal pleura meet and become continuous, the pleura extends inferiorly as a double-layered fold called the pulmonary ligament. It is an "empty" fold, contributing to the stability of the lower lobe and allowing for movement of the pulmonary vessels during respiration.

Blood Supply of the Bronchial Tree and Lungs

The lungs receive a dual blood supply: a pulmonary circulation for gas exchange and a bronchial circulation for nourishing the lung tissues.

A. Pulmonary Circulation (For Gas Exchange)

- Pulmonary Arteries: The pulmonary trunk arises from the right ventricle and divides into the right and left pulmonary arteries. These arteries carry deoxygenated blood to the lungs.

- They generally follow the branching pattern of the bronchial tree, dividing into lobar, segmental, and subsegmental arteries, accompanying every bronchus down to the respiratory bronchioles.

- Pulmonary Veins: Typically two pulmonary veins from each lung (superior and inferior) carry oxygenated blood back to the left atrium. They generally run independently of the bronchial tree, mainly between the bronchopulmonary segments.

B. Bronchial Circulation (For Tissue Nutrition)

- Bronchial Arteries:

- Origin: The bronchial arteries supply the non-respiratory tissues of the lungs. They typically arise directly from the thoracic aorta or one of its intercostal branches.

- Number: There is usually one right bronchial artery (often arising from an upper posterior intercostal artery or the left upper bronchial artery) and two left bronchial arteries.

- Distribution: They supply the walls of the bronchial tree (from the trachea down to the terminal bronchioles), the visceral pleura, connective tissue, and lymph nodes of the lungs. They also supply the pleura.

- Bronchial Veins:

- Drainage: Most of the blood supplied by the bronchial arteries drains into the pulmonary veins (mixing with oxygenated blood, leading to a physiological shunt).

- However, some drainage occurs via the bronchial veins:

- Right Bronchial Veins: Drain into the azygos vein.

- Left Bronchial Veins: Drain into the accessory hemiazygos vein or the left superior intercostal vein.

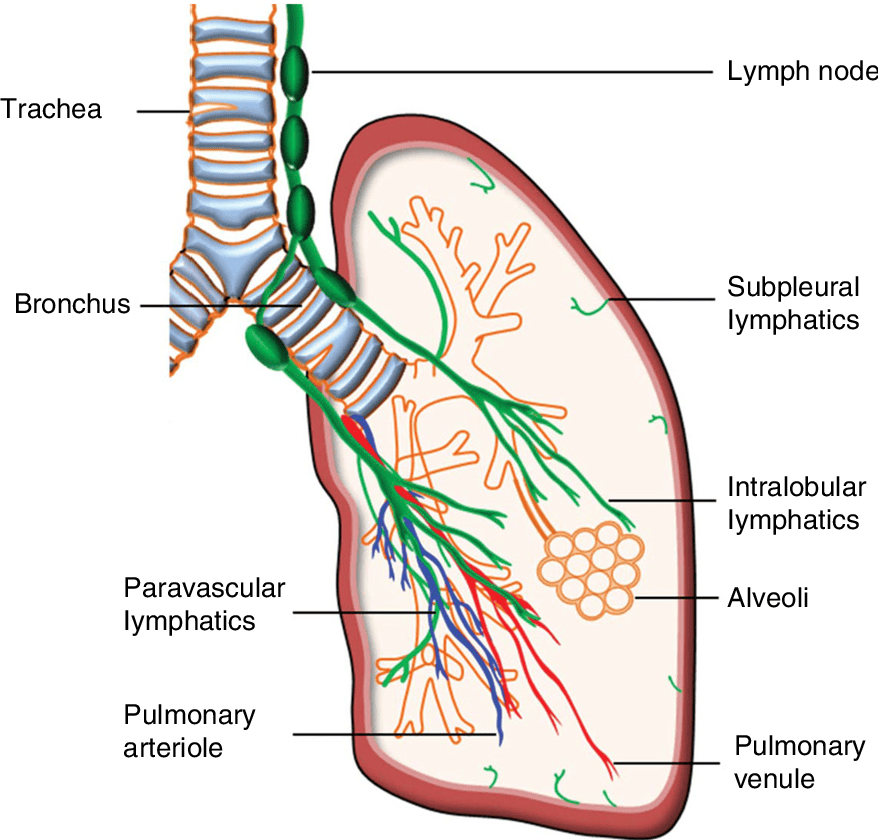

Lymphatic Drainage of the Lungs and Pleura

The lungs have a rich lymphatic network that plays a crucial role in maintaining fluid balance and immune surveillance.

Two Sets of Lymphatic Plexuses:

- Superficial (Subpleural) Plexus: Lies deep to the visceral pleura. It drains the visceral pleura and the superficial lung parenchyma.

- Deep (Bronchopulmonary) Plexus: Located in the submucosa of the bronchi and in the connective tissue surrounding the bronchi and pulmonary arteries. It drains the lung parenchyma, including the bronchi and structures around the hilum.

Pathways of Drainage (generally towards the hilum):

- Superficial plexus drains into bronchopulmonary (hilar) lymph nodes.

- Deep plexus drains into pulmonary lymph nodes (within the lung substance, near the larger bronchi) and then to the bronchopulmonary (hilar) lymph nodes.

- From the bronchopulmonary (hilar) lymph nodes (located at the hilum, just within and outside the lung substance), lymph ascends to the tracheobronchial lymph nodes (superior and inferior groups), which are situated along the trachea and main bronchi.

- From the tracheobronchial nodes, lymph drains into the paratracheal lymph nodes.

- Finally, efferent vessels from the paratracheal nodes form the bronchomediastinal trunks, which typically drain into the deep cervical lymph nodes or directly into the brachiocephalic veins (or the junction of the internal jugular and subclavian veins, i.e., the venous angle).

IV. Clinical Correlates of the Lungs and Pleura

Understanding the anatomy of the lungs and pleura is fundamental to diagnosing and treating a wide range of pulmonary conditions.

A. Pleural Pathologies (Fluid/Air in Pleural Cavity)

- Pneumothorax: The presence of air in the pleural cavity. This can cause the lung to collapse.

- a. Causes: Spontaneous (rupture of a bleb), traumatic (penetrating chest injury), iatrogenic (medical procedure).

- b. Symptoms: Sudden chest pain, shortness of breath.

- Hemothorax: The presence of blood in the pleural cavity.

- a. Causes: Trauma (ruptured blood vessels), malignancy, iatrogenic.

- Pleural Effusion: The accumulation of excess fluid in the pleural cavity. This is a general term.

- a. Causes: Heart failure, pneumonia, cancer, kidney disease, liver disease.

- Chylothorax: The accumulation of lymph (chyle) in the pleural cavity.

- a. Causes: Disruption of the thoracic duct (e.g., trauma, surgery, malignancy).

- Pleuritis (Pleurisy): Inflammation of the pleura, typically causing sharp chest pain that worsens with breathing or coughing.

B. Bronchial Tree Pathologies & Procedures

- Foreign Body Aspiration:

- a. Anatomical Predisposition: As previously discussed, the right main bronchus is wider, shorter, and more vertical than the left, making it the most common site for aspirated foreign bodies, especially in children.

- b. Clinical Relevance: Can cause airway obstruction, infection, or lung damage. Requires prompt removal, often by bronchoscopy.

- Chest Physiotherapy (Postural Drainage):

- a. Purpose: Techniques used to help clear mucus and secretions from the lungs.

- b. Application: Particularly important in conditions like cystic fibrosis where thick, sticky mucus accumulates in the airways. Patients are positioned to use gravity to drain secretions from specific bronchopulmonary segments into larger airways, where they can be coughed out. Knowledge of segmental anatomy is crucial for effective postural drainage.

- Bronchoscopy: A procedure where a flexible or rigid tube with a camera is inserted into the airways to visualize the trachea and bronchi, obtain biopsies, remove foreign bodies, or suction secretions.

C. Diagnostic & Therapeutic Procedures

- Thoracoscopy:

- a. Procedure: A minimally invasive surgical procedure where an endoscope is inserted into the pleural cavity through small incisions in the chest wall.

- b. Uses: Diagnosis and treatment of pleural diseases, lung biopsies, and staging of lung cancer.

- Pulmonary Embolism (PE):

- a. Pathology: Blockage of a pulmonary artery by an embolus (most commonly a blood clot originating from deep veins in the legs).

- b. Severity: Can range from asymptomatic to life-threatening, depending on the size and location of the embolism.

- Pulmonary Embolectomy:

- a. Procedure: Surgical removal of a pulmonary embolus from the pulmonary arteries.

- b. Indication: Reserved for massive, life-threatening pulmonary emboli when less invasive treatments (e.g., thrombolysis) are contraindicated or unsuccessful.

https://www.doctorsrevisionuganda.com | Whatsapp: 0726113908

Lower Respiratory Tract Quiz

Systems Anantomy

Enter your details to begin the examination.

🛡️ Privacy Note: Results are for tracking and certification purposes only.

Lower Respiratory Tract Quiz

Systems Anantomy

Preparing questions...

Exam Completed!

See your performance breakdown below.