Integrated Metabolism & : Fuel Homeostasis

Integrated Metabolism and Fuel Homeostasis

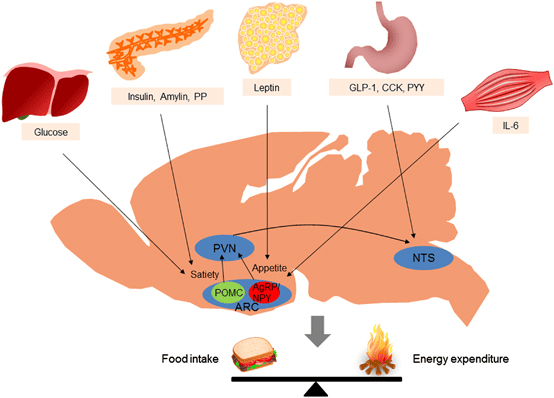

Fuel Homeostasis refers to the dynamic equilibrium and finely tuned regulation of energy substrates (glucose, fatty acids, ketone bodies, amino acids) in the body. Its primary goal is to ensure a continuous and adequate supply of fuel to all tissues, particularly the brain, under varying physiological conditions.

It is crucial for survival, allowing the body to adapt to fluctuations in nutrient availability and energy demand. Disruptions lead to metabolic diseases like diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome.

Key Metabolic Organs and Their Specialized Roles

The human body is a highly integrated system where different organs specialize in fuel storage, production, and utilization.

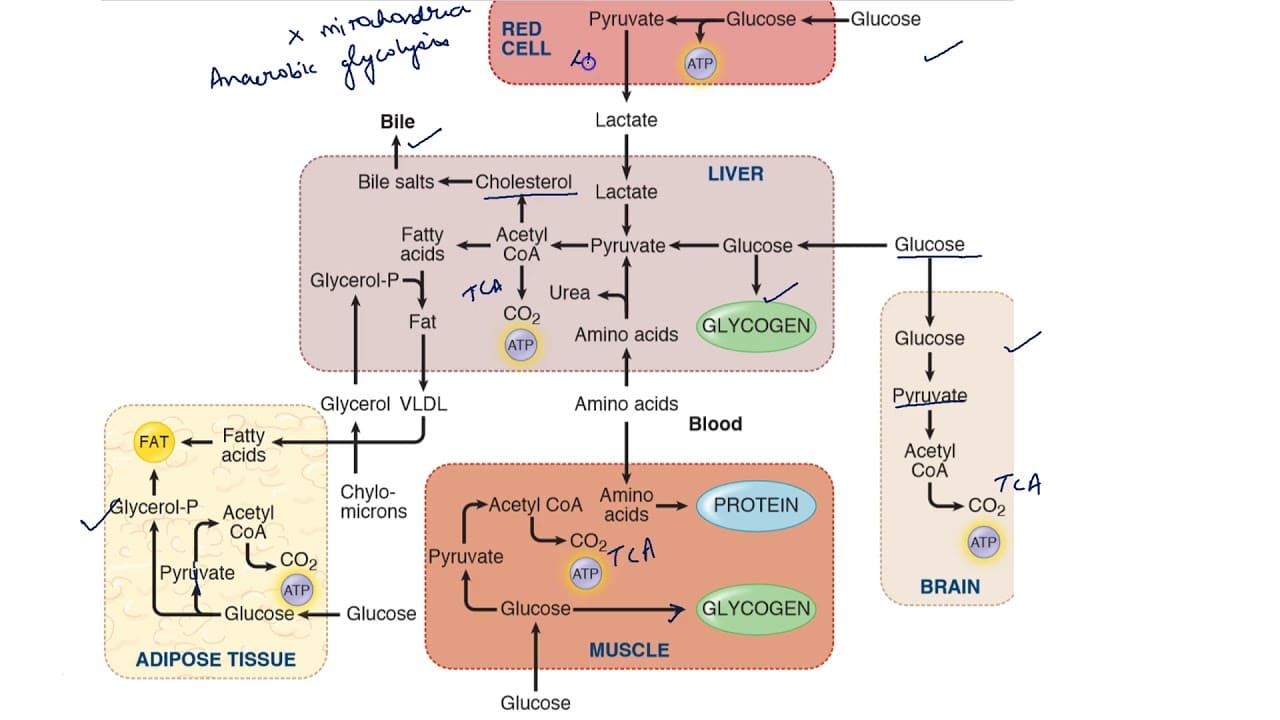

Liver (Hepatocytes): The Metabolic Hub

- Glucose Homeostasis: Central to maintaining blood glucose levels.

- Fed State: Takes up excess glucose, converting it to glycogen (glycogenesis) or fatty acids (lipogenesis).

- Fasting State: Releases glucose into the blood via glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis.

- Lipid Metabolism: Site of de novo fatty acid synthesis, cholesterol synthesis, and VLDL assembly. It is also the primary site for ketogenesis during prolonged fasting.

- Amino Acid Metabolism: Site for amino acid uptake, protein synthesis, deamination, and the urea cycle.

- Lack of Ketone Body Utilization: Cannot use ketone bodies as fuel due to the absence of thiophorase.

Adipose Tissue (Adipocytes): The Energy Storehouse

- Storage: Primary site for the long-term storage of energy as triacylglycerols (TAGs).

- Mobilization: Releases free fatty acids and glycerol via lipolysis during fasting.

- Synthesis: Can synthesize TAGs from fatty acids and glycerol-3-phosphate.

- Endocrine Organ: Produces adipokines (e.g., leptin, adiponectin).

Skeletal Muscle (Myocytes): The Major Energy Consumer

- Fuel Utilization: Highly versatile; can use glucose, fatty acids, and ketone bodies.

- Glycogen Storage: Stores significant amounts of glycogen, but only for its own use (lacks glucose-6-phosphatase).

- Fatty Acid Oxidation: Major site for fatty acid oxidation, particularly during exercise and fasting.

- Protein Reservoir: A significant protein reserve that can be catabolized during prolonged fasting.

Brain (Neurons and Glial Cells): Obligate Glucose User, Adaptable in Fasting

- Primary Fuel: Under normal conditions, relies almost exclusively on glucose.

- Adaptation in Fasting: During prolonged fasting, the brain can adapt to utilize ketone bodies as a significant alternative fuel, sparing muscle protein.

- Cannot use Fatty Acids: Fatty acids cannot cross the blood-brain barrier.

Pancreas (Islets of Langerhans): The Endocrine Regulator

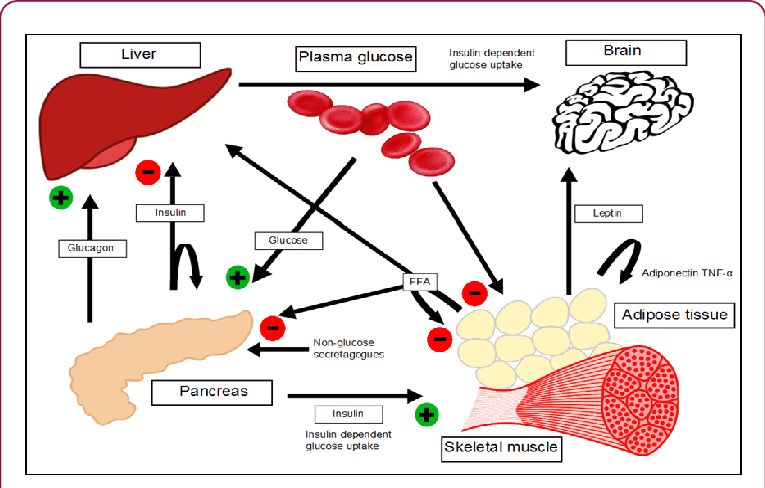

- Insulin (Beta Cells): Released in response to high blood glucose (fed state). Promotes fuel storage.

- Glucagon (Alpha Cells): Released in response to low blood glucose (fasting state). Promotes fuel mobilization.

- Somatostatin (Delta Cells): Inhibits secretion of both insulin and glucagon.

Major Hormones Orchestrating Fuel Homeostasis

These hormones act synergistically and antagonistically to maintain metabolic balance.

Insulin (Anabolic Hormone)

- Source: Pancreatic β-cells.

- Stimulus: High blood glucose, amino acids.

- Overall Effect: Promotes fuel storage; lowers blood glucose.

- Actions:

- Liver: Increases glycogenesis, lipogenesis; inhibits glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis.

- Muscle: Increases glucose uptake (via GLUT4), glycogenesis, protein synthesis.

- Adipose: Increases glucose uptake (via GLUT4), TAG synthesis; inhibits lipolysis (inhibits HSL).

Glucagon (Catabolic Hormone)

- Source: Pancreatic α-cells.

- Stimulus: Low blood glucose.

- Overall Effect: Promotes fuel mobilization; raises blood glucose.

- Actions (primarily liver): Increases glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, ketogenesis; inhibits glycogenesis, lipogenesis.

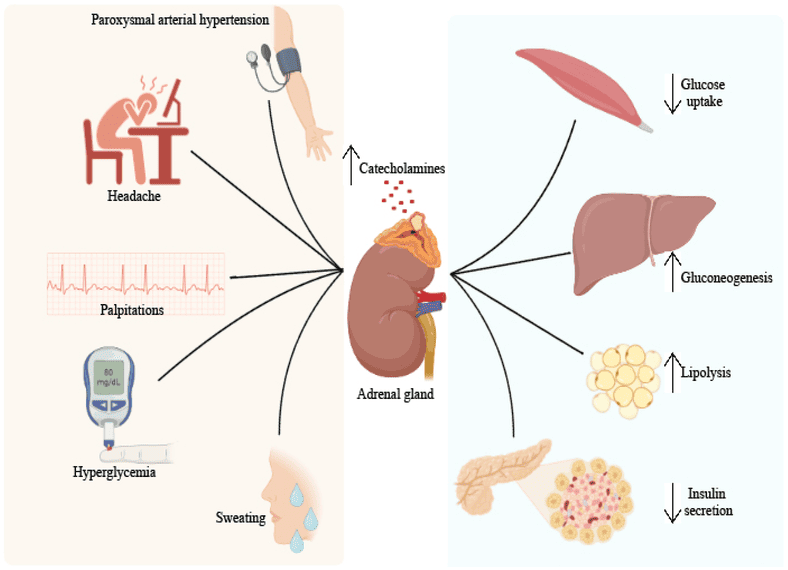

Catecholamines (Epinephrine, Norepinephrine - Stress Hormones)

- Source: Adrenal medulla, sympathetic nervous system.

- Stimulus: Stress, exercise, hypoglycemia.

- Overall Effect: "Fight or flight"; rapid mobilization of energy stores.

- Actions:

- Liver & Muscle: Increases glycogenolysis.

- Adipose: Potent activator of HSL, promoting lipolysis.

Cortisol (Glucocorticoid - Stress Hormone)

- Source: Adrenal cortex.

- Stimulus: Stress (chronic), low blood glucose.

- Overall Effect: Sustained glucose production; catabolic.

- Actions:

- Liver: Increases gluconeogenesis (by increasing enzyme synthesis).

- Muscle: Increases protein breakdown.

- Adipose: Increases lipolysis.

- Decreases peripheral glucose utilization.

The Fed State (Post-prandial Metabolism)

The fed state is characterized by nutrient absorption from the gastrointestinal tract, leading to elevated levels of glucose, amino acids, and triacylglycerols in the blood. The body's primary response is to store these excess nutrients and utilize glucose as the main fuel.

A. High Insulin:Glucagon Ratio:

- Following a meal, especially one rich in carbohydrates, blood glucose levels rise.

- This rise in glucose stimulates the pancreatic β-cells to release insulin.

- Simultaneously, high glucose inhibits the pancreatic α-cells, suppressing glucagon secretion.

- The resulting high insulin:glucagon ratio orchestrates the anabolic (storage) and glucose-utilizing responses.

B. Carbohydrate Metabolism: Glucose as the Primary Fuel and for Storage

Tissue-Specific Glucose Uptake and Utilization:

Liver:

- High Priority Uptake: Glucose enters hepatocytes via GLUT2 transporters.

- Phosphorylation: Glucokinase rapidly phosphorylates glucose to Glucose-6-Phosphate, trapping it inside.

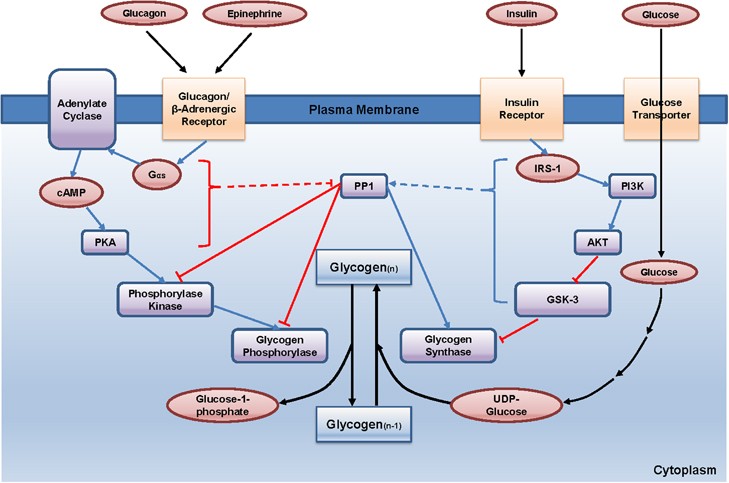

- Glycogenesis (Glycogen Synthesis): G6P is directed towards glycogen synthesis. Insulin activates glycogen synthase.

- Glycolysis and Pyruvate Oxidation: Excess G6P enters glycolysis, and the resulting pyruvate is converted to Acetyl-CoA.

- Lipogenesis (Fatty Acid Synthesis): When energy and glycogen stores are full, Acetyl-CoA is channeled into de novo fatty acid synthesis. Insulin stimulates this process by activating Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (ACC).

- VLDL Synthesis: Newly synthesized fatty acids are esterified to form TAGs, which are packaged into Very-Low-Density Lipoproteins (VLDL) and secreted into the bloodstream.

Adipose Tissue (Adipocytes):

- Insulin-Dependent Glucose Uptake: Insulin stimulates the translocation of GLUT4 transporters to the cell membrane.

- Glycerol-3-Phosphate Production: Glucose undergoes glycolysis to produce glycerol-3-phosphate, essential for esterifying fatty acids into TAGs.

- Fatty Acid Uptake: Adipose tissue takes up fatty acids from chylomicrons and VLDL via the action of Lipoprotein Lipase (LPL), which is activated by insulin.

Skeletal Muscle:

- Insulin-Dependent Glucose Uptake: Insulin stimulates GLUT4 translocation, increasing glucose uptake.

- Glycogenesis: Muscle cells synthesize glycogen for their own energy reserves.

- Glycolysis and Oxidation: Glucose is used as a primary fuel source for ATP production.

Brain:

- Insulin-Independent Glucose Uptake: Glucose uptake occurs via GLUT1 and GLUT3 transporters, ensuring a constant supply.

- High Glucose Utilization: The brain consumes a significant amount of glucose (about 120g/day).

C. Lipid Metabolism: Storage and Transport

- Dietary Fat Absorption and Chylomicron Formation: Dietary TAGs are hydrolyzed, absorbed, and then re-esterified within enterocytes. These TAGs are packaged into chylomicrons and released into the lymph and then the bloodstream.

- Chylomicron Metabolism: As chylomicrons circulate, their TAGs are hydrolyzed by Lipoprotein Lipase (LPL), an enzyme activated by insulin. This promotes the uptake of fatty acids into adipose tissue (for storage) and muscle (for use).

- Hepatic VLDL Production: As mentioned, the liver converts excess glucose into fatty acids, which are packaged as TAGs into VLDL particles and secreted. Like chylomicrons, VLDL TAGs are acted upon by LPL.

D. Amino Acid Metabolism: Protein Synthesis

- Amino Acid Absorption: Dietary proteins are digested into amino acids and transported to the liver via the portal circulation.

- Tissue-Specific Utilization:

- Liver: Uses amino acids for liver protein synthesis, synthesis of plasma proteins (e.g., albumin), and synthesis of non-protein nitrogenous compounds. Excess amino acids can be deaminated and their carbon skeletons used for energy or lipogenesis.

- Skeletal Muscle: Insulin promotes the uptake of amino acids. The primary fate is protein synthesis, to repair and build muscle mass.

- Other Tissues: Amino acids are taken up for the synthesis of new proteins and other molecules.

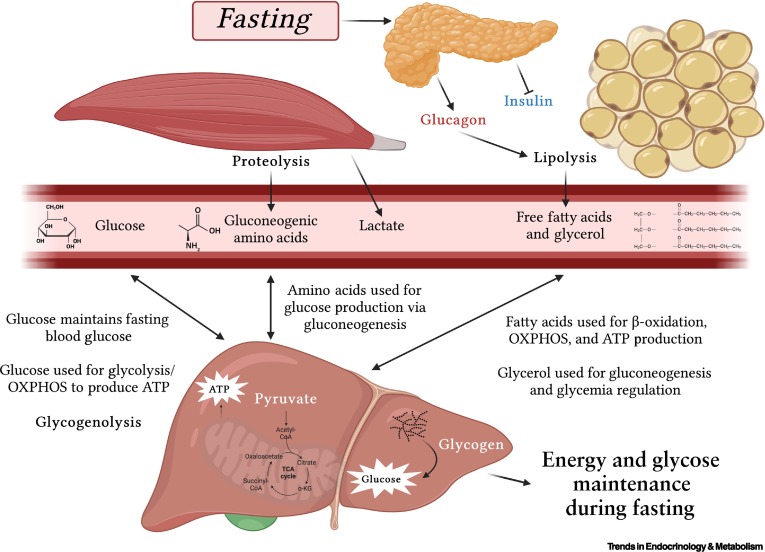

The Fasting State (Early Fasting, Overnight Fast)

The fasting state is characterized by the absence of nutrient intake. The body must now shift from storing fuels to mobilizing its endogenous reserves to maintain a steady supply of energy, especially for the brain. This transition is orchestrated by a low insulin:glucagon ratio.

A. Low Insulin:High Glucagon Ratio:

- As blood glucose levels fall, pancreatic β-cells reduce insulin secretion.

- Concurrently, falling glucose stimulates pancreatic α-cells to increase glucagon secretion.

- The resulting low insulin:high glucagon ratio is the primary signal that triggers the mobilization of stored fuels and the production of new glucose.

- Catecholamines (epinephrine, norepinephrine) and cortisol also play supportive roles.

B. Carbohydrate Metabolism: Glucose Production and Sparing

The primary goal is to maintain blood glucose levels for the brain and other glucose-dependent tissues.

Glycogenolysis (Glycogen Breakdown):

- Liver Glycogen: This is the first line of defense. Hepatic glycogen is rapidly mobilized, stimulated by glucagon and epinephrine. The resulting glucose-6-phosphate is dephosphorylated by glucose-6-phosphatase (present only in the liver) to release free glucose into the blood.

- Duration: Liver glycogen can maintain blood glucose for about 12-24 hours.

- Muscle Glycogen: Muscle glycogen is used only by the muscle itself for energy and cannot be released into the blood.

Gluconeogenesis (New Glucose Synthesis):

- As liver glycogen is depleted, gluconeogenesis becomes the primary mechanism for maintaining blood glucose. This is highly active in the liver.

- Substrates for Gluconeogenesis:

- Lactate: From anaerobic glycolysis in red blood cells.

- Glycerol: Released from the breakdown of TAGs in adipose tissue.

- Glucogenic Amino Acids: Derived from protein breakdown, primarily in skeletal muscle.

- Hormonal Regulation: Glucagon and cortisol are major stimulators.

Glucose Sparing:

To conserve glucose for the brain, other tissues switch their fuel preference to fatty acids and ketone bodies.

C. Lipid Metabolism: Mobilization of Stored Fat

Lipolysis in Adipose Tissue:

- Hormone-Sensitive Lipase (HSL): Glucagon and catecholamines activate HSL in adipocytes via a cAMP-dependent cascade.

- HSL hydrolyzes stored TAGs into free fatty acids (FFAs) and glycerol.

- FFAs: Released into the bloodstream, bind to albumin, and are transported to tissues for β-oxidation.

- Glycerol: Released into the bloodstream and travels to the liver to serve as a substrate for gluconeogenesis.

Fatty Acid Oxidation (β-Oxidation):

- Liver: Becomes a major site of fatty acid oxidation, providing ATP for gluconeogenesis. Excess Acetyl-CoA fuels ketogenesis.

- Skeletal Muscle, Heart, Kidneys: Utilize fatty acids as their primary fuel, thereby sparing glucose.

Ketogenesis (Ketone Body Formation):

- Location: Liver mitochondria.

- Stimulus: High rate of fatty acid oxidation in the liver produces large amounts of Acetyl-CoA. When the TCA cycle is saturated (due to OAA being diverted for gluconeogenesis), the excess Acetyl-CoA is diverted to ketone body synthesis.

- Products: Acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate.

- Purpose: Ketone bodies are water-soluble fuels that can be transported to extrahepatic tissues, particularly the brain, muscle, and heart.

D. Amino Acid Metabolism: Protein Breakdown for Glucose Production

Protein Breakdown in Muscle:

- As fasting continues, skeletal muscle protein becomes a significant source of amino acids for gluconeogenesis. Cortisol promotes this breakdown.

- Glucogenic Amino Acids: Released into the bloodstream and transported to the liver (e.g., alanine, glutamine).

- Alanine Cycle (Cahill Cycle): Pyruvate in muscle is transaminated to alanine, which travels to the liver. In the liver, alanine is converted back to pyruvate for gluconeogenesis.

- Glutamine: Plays a major role in transporting amino groups from muscle to the liver and kidneys.

Urea Cycle:

The amino groups removed from amino acids are converted to ammonia, which is detoxified in the liver via the urea cycle, producing urea for excretion. The rate of the urea cycle increases during fasting.

In summary, the early fasting state is a period of catabolism driven by a low insulin:glucagon ratio. The body prioritizes maintaining blood glucose through glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, while other tissues shift to fatty acid oxidation. Ketone body production begins to ramp up, setting the stage for their increased utilization in prolonged starvation.

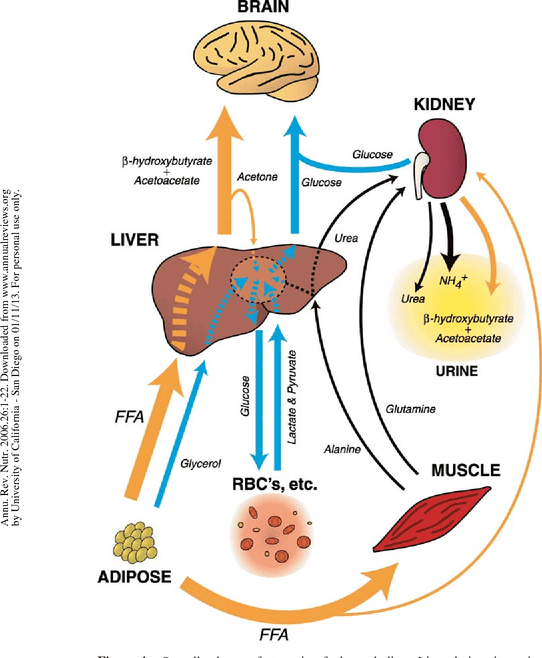

The Starved State (Prolonged Fasting/Starvation)

The starved state represents an extended period of nutrient deprivation, pushing the body's metabolic adaptations to their limits. The primary goals shift to:

- Glucose Sparing: Minimizing the use of glucose by peripheral tissues.

- Protein Sparing: Reducing the breakdown of essential muscle protein.

- Increased Reliance on Fat and Ketone Bodies: Maximizing energy production from abundant fat stores.

A. Continued Low Insulin:High Glucagon Ratio (and elevated stress hormones):

- The hormonal profile established in early fasting persists and may even intensify.

- Insulin levels remain very low, while glucagon, cortisol, and epinephrine remain elevated, reinforcing the catabolic drive.

B. Carbohydrate Metabolism: Extreme Glucose Sparing and Gluconeogenesis Adaptation

Liver Glycogen Depletion:

By the time the starved state is reached (typically after 24-48 hours), liver glycogen stores are almost completely depleted. The body can no longer rely on glycogenolysis.

Sustained Gluconeogenesis (but with changing substrates):

- Gluconeogenesis remains the sole source of new glucose, with kidney gluconeogenesis becoming increasingly significant (up to 40-50% of total production).

- Shift in Substrates:

- Glycerol: Becomes a relatively constant source due to ongoing lipolysis.

- Amino Acids: The rate of muscle protein breakdown decreases significantly after several days/weeks. This is a crucial adaptation to preserve essential lean body mass. The contribution of amino acids to gluconeogenesis gradually declines.

- Lactate: Continues to contribute to a minor extent.

Brain's Adaptation to Ketone Bodies (Glucose Sparing):

- This is the most critical adaptation in the starved state. The brain significantly increases its utilization of ketone bodies (β-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate) for energy.

- Mechanism: Ketone bodies cross the blood-brain barrier and are converted back to Acetyl-CoA for the TCA cycle.

- Impact: By shifting to ketone bodies, the brain dramatically reduces its demand for glucose (from ~120g/day to as low as 30-40g/day). This reduces the need for gluconeogenesis from amino acids, thereby sparing muscle protein.

C. Lipid Metabolism: Maximized Mobilization and Ketone Body Production

Maximized Lipolysis:

Lipolysis in adipose tissue continues at a very high rate, providing a continuous supply of fatty acids (for fuel) and glycerol (for gluconeogenesis). Fat stores are the largest energy reserve.

Massive Ketogenesis:

The liver's production of ketone bodies reaches its peak. The high influx of fatty acids, coupled with the low insulin state, promotes maximal β-oxidation and subsequent conversion of Acetyl-CoA into acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate. Blood ketone body levels rise to very high concentrations, serving as the primary fuel for the brain, heart, and skeletal muscle.

D. Amino Acid Metabolism: Protein Sparing and Reduced Nitrogen Excretion

Reduced Muscle Protein Breakdown:

After an initial period of high protein catabolism, the body adapts to significantly reduce muscle protein breakdown. This is directly linked to the brain's increased use of ketone bodies, as less glucose needs to be synthesized from amino acids. This adaptation is critical for long-term survival.

Decreased Urea Production:

As amino acid catabolism decreases, the amount of nitrogen released also decreases. Consequently, the liver's production of urea via the urea cycle significantly declines. This is reflected in a reduced excretion of urea in the urine, signifying the shift to protein-sparing metabolism.

Summary of the Starved State: The starved state is characterized by extreme adaptations aimed at survival. The body shifts almost entirely to fat and ketone body metabolism to preserve its vital protein reserves. The brain becomes a major consumer of ketone bodies, dramatically reducing its glucose requirement and allowing for a significant reduction in the breakdown of muscle protein. This allows individuals to survive for extended periods without food.

Diabetes Mellitus as a Disorder of Fuel Homeostasis

Diabetes Mellitus (DM) is a group of metabolic diseases characterized by hyperglycemia (high blood glucose) resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. This chronic hyperglycemia is associated with long-term damage and failure of various organs.

The core problem is a breakdown in the body's ability to regulate glucose, leading to a state that inappropriately resembles a constant "fasted" or even "starved" state in some tissues, despite abundant glucose in the blood.

A. Overview of Types of Diabetes:

Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM): Absolute Insulin Deficiency

- Cause: Autoimmune destruction of the pancreatic β-cells, leading to an absolute deficiency of insulin production.

- Onset: Typically in childhood or adolescence.

- Metabolic State: Resembles a perpetual, severe starved state because glucose cannot enter insulin-dependent cells.

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM): Insulin Resistance with Relative Insulin Deficiency

- Cause: A combination of insulin resistance (target cells fail to respond to insulin) and progressive pancreatic β-cell dysfunction.

- Onset: Typically in adulthood, but increasingly seen in adolescents.

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM):

- Cause: Insulin resistance that develops during pregnancy, often resolving after childbirth but increasing future risk of T2DM.

B. Metabolic Consequences of Absolute Insulin Deficiency (Type 1 Diabetes)

This leads to a profound metabolic crisis, an exaggerated fasted state, if untreated.

Hyperglycemia (High Blood Glucose):

- Increased Hepatic Glucose Production: Unchecked glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis due to unopposed glucagon.

- Decreased Glucose Utilization: Insulin-dependent tissues (muscle, adipose) cannot take up glucose due to the lack of GLUT4 translocation.

- Result: Blood glucose soars, leading to osmotic diuresis (excessive urination) and thirst (polydipsia).

Increased Lipolysis and Hypertriglyceridemia:

- Unchecked Lipolysis: The absence of insulin means Hormone-Sensitive Lipase (HSL) is constantly active, leading to massive breakdown of stored TAGs.

- Increased Fatty Acids & VLDL: High levels of free fatty acids are released, and the liver continuously synthesizes VLDL, leading to high blood triglycerides.

Exaggerated Ketogenesis and Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA):

- This is a life-threatening complication of uncontrolled T1DM.

- Mechanism: A high influx of fatty acids to the liver, coupled with their rapid β-oxidation, generates huge amounts of Acetyl-CoA. Uninhibited ketogenesis converts this Acetyl-CoA into ketone bodies.

- Metabolic Acidosis: The ketone bodies (acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate) are strong acids. Their overproduction overwhelms the body's buffering capacity, causing blood pH to drop.

- Symptoms: Nausea, fruity breath (due to acetone), Kussmaul respiration (deep, labored breathing), confusion, and coma.

Protein Catabolism and Muscle Wasting:

The absence of insulin inhibits protein synthesis and promotes muscle protein breakdown. The released amino acids contribute to hepatic gluconeogenesis, exacerbating hyperglycemia and leading to significant weight loss.

C. Metabolic Consequences of Insulin Resistance (Type 2 Diabetes):

Hyperglycemia:

- Insulin Resistance in Muscle/Adipose: Reduced glucose uptake.

- Insulin Resistance in Liver: Fails to suppress hepatic glucose production.

- β-cell Dysfunction: Eventually, insulin secretion becomes inadequate to overcome resistance.

Dyslipidemia:

Insulin resistance leads to increased lipolysis, increased VLDL production, low HDL cholesterol, and the formation of small, dense LDL particles, increasing cardiovascular disease risk.

Less Prone to Ketoacidosis:

Patients with T2DM usually produce some insulin, which is often enough to suppress massive ketogenesis. A more common acute complication is Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS), characterized by extreme hyperglycemia and dehydration without significant ketoacidosis.

D. Key Principles of Treatment:

Type 1 Diabetes:

- Insulin Replacement: Essential for survival.

- Diet and Exercise: Crucial for managing blood glucose.

Type 2 Diabetes:

- Lifestyle Modifications: Diet and exercise are foundational.

- Oral Medications: Metformin (reduces hepatic glucose production), Sulfonylureas (stimulate insulin secretion), and others.

- Insulin Therapy: May be required as the disease progresses.

Biochemistry: Integrated Metabolism

Fuel Homeostasis

Test your knowledge with these 30 questions.

Integrated Metabolism Quiz

Question 1/30

Quiz Complete!

Here are your results, .

Your Score

27/30

90%