Hypothalamus & Pituitary Gland Physiology

INTRODUCTION TO THE HYPOTHALAMUS & PITUITARY GLAND

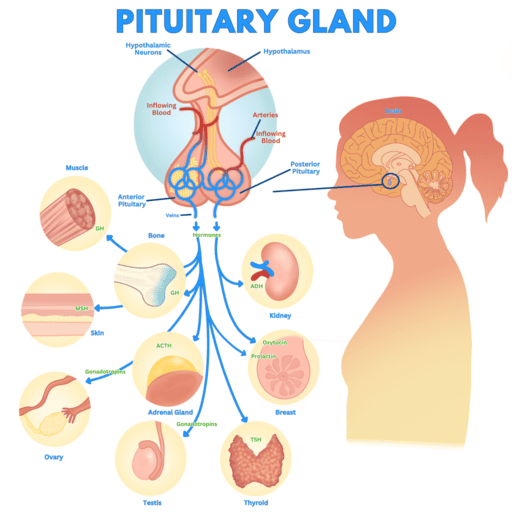

The hypothalamus and pituitary gland form a crucial functional unit at the base of the brain, acting as the primary link between the nervous system and the endocrine system. Together, they regulate virtually all hormonal functions of the body, maintaining homeostasis, governing growth, metabolism, reproduction, and stress responses.

- The hypothalamus, a small but immensely powerful region of the diencephalon, serves as the command center, integrating neural signals from the brain and translating them into hormonal signals.

- The pituitary gland (also known as the hypophysis), often dubbed the "master gland," receives these signals from the hypothalamus and, in turn, secretes hormones that control other endocrine glands throughout the body.

FUNCTIONS OF THE HYPOTHALAMUS

The hypothalamus is a highly specialized region of the brain responsible for maintaining various homeostatic functions and integrating responses to internal and external stimuli. Its diverse functions include:

1. Autonomic Nervous System Regulation

The hypothalamus is a major control center for the autonomic nervous system (ANS), influencing both its sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions. It regulates involuntary functions such as heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, respiration, and pupil dilation, adapting the body's internal environment to changing conditions.

2. Hormone Production

The hypothalamus itself produces several hormones. These include:

- Releasing hormones and inhibiting hormones that control the secretion of hormones from the anterior pituitary.

- Antidiuretic hormone (ADH, or vasopressin) and oxytocin, which are synthesized in the hypothalamic nuclei and then transported to the posterior pituitary for storage and release.

3. Endocrine Regulation

This is a primary function. Through its production of releasing and inhibiting hormones, the hypothalamus controls the secretion of nearly all anterior pituitary hormones, thereby indirectly regulating many other endocrine glands (e.g., thyroid, adrenal cortex, gonads).

4. Circadian Rhythm Regulation

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) within the hypothalamus acts as the body's primary biological clock, regulating circadian rhythms such as the sleep-wake cycle, body temperature, and hormone secretion patterns in response to light-dark cues.

5. Limbic System Interaction

The hypothalamus is intimately connected with the limbic system, the part of the brain involved in emotion, motivation, and memory. This connection allows the hypothalamus to integrate emotional responses with physiological functions, influencing behaviors like feeding, aggression, and sexual drive.

6. Integration of Basic Drives

It is involved in regulating fundamental physiological drives and behaviors, such as thirst, hunger, satiety, sexual behavior, and defensive reactions.

7. Temperature Regulation

The hypothalamus contains specialized thermoreceptors and serves as the body's thermostat. It initiates physiological responses (e.g., sweating, shivering, vasodilation/vasoconstriction) to maintain a stable core body temperature within a narrow range.

8. Feeding

Specific nuclei within the hypothalamus (e.g., ventromedial nucleus for satiety, lateral hypothalamus for hunger) play critical roles in regulating food intake and energy balance.

THE PITUITARY GLAND (HYPOPHYSIS, MASTER GLAND)

The pituitary gland is a small, pea-sized endocrine gland, approximately 1 cm in diameter and weighing about 0.5 to 1 gram. It is strategically located within the sella turcica, a bony cavity at the base of the brain, protecting it from injury.

The pituitary gland is functionally and anatomically connected to the hypothalamus by the pituitary stalk (or hypophysial stalk/infundibulum), a slender structure containing blood vessels and nerve fibers.

Structurally and functionally, the pituitary gland is divided into two distinct lobes:

- Anterior Pituitary Lobe (Adenohypophysis): Constitutes about two-thirds of the gland.

- Posterior Pituitary Lobe (Neurohypophysis): Constitutes about one-third of the gland.

A. THE ANTERIOR PITUITARY LOBE (ADENOHYPOPHYSIS)

The anterior pituitary is an endocrine gland in its own right, synthesizing and secreting a variety of vital hormones.

- Pars Intermedia: In the fetus, there is a small, avascular tissue called the pars intermedia located between the anterior and posterior lobes. It is much more functional in some lower animals (fish, amphibians, reptiles) but is largely vestigial and no longer present as a distinct functional unit in adult humans, though some of its cells may be dispersed within the anterior lobe.

- Adult Structure: In adults, the anterior pituitary consists of two main parts:

- Pars Distalis: This is the rounded, major endocrine part of the gland, responsible for secreting most of the anterior pituitary hormones. This is what is commonly referred to as the "anterior pituitary."

- Pars Tuberalis: A thin, upward extension that wraps around the infundibulum (pituitary stalk). Its precise function in humans is less understood but is believed to contribute to seasonal and circadian rhythms.

The Anterior Pituitary Gland Cells:

Histologically, the anterior pituitary contains various types of secretory cells, traditionally classified by their staining properties as chromophils (acidophils and basophils) or chromophobes. Each cell type is typically responsible for producing a specific hormone or hormones:

Chromophils: Acidophils

- Somatotropes: Constitute approximately 30-40% of anterior pituitary cells and secrete human Growth Hormone (hGH).

- Lactotropes (or Mammotropes): Constitute approximately 3-5% of anterior pituitary cells and secrete Prolactin (PRL).

Chromophils: Basophils

- Corticotropes: Constitute approximately 20% of anterior pituitary cells and secrete Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH).

- Thyrotropes: Constitute approximately 3-5% of anterior pituitary cells and secrete Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH).

- Gonadotropes: Constitute approximately 3-5% of anterior pituitary cells and secrete the gonadotropic hormones: Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH).

Embryological Origin: The anterior pituitary is embryologically derived from Rathke's pouch, an upward invagination of epithelial tissue from the roof of the primitive pharynx (mouth). This epithelial origin distinguishes it from the posterior pituitary, which has a neural origin.

B. THE POSTERIOR PITUITARY LOBE (NEUROHYPOPHYSIS)

The posterior pituitary is functionally an extension of the hypothalamus, serving as a storage and release site for hormones produced by hypothalamic neurons.

- Embryological Origin: It is embryologically derived from a downward outgrowth of nervous tissue from the hypothalamus. This neural origin explains its structural and functional connection to the brain.

- Structure: It is in direct contact with the infundibulum (pituitary stalk) and physically associated with the adenohypophysis. It consists mainly of the Pars Nervosa, which is essentially a collection of axons and nerve terminals originating from the hypothalamus, along with specialized glial cells called pituicytes.

- Neural Part: The posterior pituitary is distinctly the neural part of the pituitary gland. It does not synthesize hormones itself but stores and releases hormones produced by the hypothalamus.

HYPOTHALAMIC CONTROL OF PITUITARY SECRETIONS

The hypothalamus exerts profound control over almost all secretions by both lobes of the pituitary gland. This control is achieved through distinct mechanisms:

- Anterior Pituitary: Controlled primarily by hormonal signals from the hypothalamus.

- Posterior Pituitary: Controlled primarily by nervous signals from the hypothalamus.

A. RELATIONSHIP WITH THE ANTERIOR PITUITARY GLAND: THE HYPOTHALAMIC-HYPOPHYSIAL PORTAL SYSTEM

The communication between the hypothalamus and the anterior pituitary is vascular, through a specialized portal system:

- Superior Hypophysial Artery: Branches off the internal carotid artery and supplies the upper part of the pituitary stalk and the median eminence (the inferior extension of the hypothalamus).

- First Capillary Network (at the Median Eminence): These arteries form a primary capillary plexus in the median eminence, where neurosecretory neurons in the hypothalamus release their hypothalamic releasing and inhibitory hormones into the blood.

- Hypophysial Portal Vessels: These capillaries then coalesce to form the hypophysial portal veins, which descend along the pituitary stalk.

- Second Capillary Network (in the Anterior Pituitary): The portal veins branch into a secondary capillary plexus within the anterior pituitary. Here, the hypothalamic hormones diffuse out of the capillaries and act directly on the specific secretory cells of the anterior pituitary, stimulating or inhibiting their hormone release.

- Venous Flow to the Heart: The anterior pituitary hormones then enter the systemic circulation via venous drainage to the heart, reaching their target organs.

This portal system ensures that the hypothalamic hormones reach the anterior pituitary in high concentrations before being diluted in the general circulation, allowing for precise control.

B. HYPOTHALAMIC CONTROL OF ANTERIOR PITUITARY SECRETIONS: RELEASING & INHIBITING HORMONES

The hypothalamus secretes a number of peptide hormones, collectively known as "hypothalamic releasing hormones" and "hypothalamic inhibitory hormones," which directly regulate the secretion of anterior pituitary hormones. Each anterior pituitary hormone generally has at least one hypothalamic regulatory hormone.

Here are some key hypothalamic nuclei and the hormones they release:

| NUCLEUS | HORMONE RELEASED |

|---|---|

| Pre-Optic Nucleus | Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH): Stimulates LH and FSH release. |

| Ventromedial Nucleus |

Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH): Stimulates GH release. Somatostatin (Growth Hormone-Inhibiting Hormone, GHIH): Inhibits GH release. |

| Paraventricular Nucleus |

Oxytocin (90%) - ADH (10%): Synthesizes these, which are released from posterior pituitary. Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH): Stimulates TSH and Prolactin release. |

| Arcuate Nucleus | Prolactin-Inhibiting Factor (PIF), which is Dopamine: Inhibits Prolactin release. |

| Supra-Optic Nucleus | ADH (90%) - Oxytocin (10%): Synthesizes these, which are released from posterior pituitary. |

RELATIONSHIP WITH THE POSTERIOR PITUITARY GLAND

Unlike the anterior pituitary, which communicates via a vascular portal system, the posterior pituitary has a direct neural connection with the hypothalamus. This makes the posterior pituitary essentially an extension of the brain itself.

- Neural Connection: The posterior pituitary gland is connected to the hypothalamus by unmyelinated nerve fibers. These nerve fibers form the hypothalamohypophysial tract.

- Location of Hormone Synthesis: The cell bodies of the neurons that produce the posterior pituitary hormones are located in specific nuclei within the hypothalamus:

- Supraoptic Nucleus: Primarily responsible for synthesizing Antidiuretic Hormone (ADH), also known as Vasopressin.

- Paraventricular Nucleus: Primarily responsible for synthesizing Oxytocin. It is crucial to understand that these hormones are synthesized in the hypothalamus, NOT in the posterior pituitary gland itself.

- Axonal Transport: The nerve fibers (axons) from these hypothalamic nuclei extend down through the infundibulum (pituitary stalk), alongside small glial-like cells called pituicytes, into the posterior pituitary.

- Storage and Release: The synthesized hormones (ADH and Oxytocin) are then transported down these axons by axoplasmic flow to the nerve terminals located in the posterior pituitary gland. They are stored in secretory granules within these nerve terminals until an appropriate stimulus triggers their release directly into the bloodstream.

In summary, the posterior pituitary gland acts as a storage and release site for hormones that are secreted (synthesized) from the hypothalamus. It does not produce its own hormones. This direct neural pathway allows for rapid and precise release of ADH and Oxytocin in response to hypothalamic signals.

ANTERIOR PITUITARY GLAND HORMONES

The anterior pituitary gland secretes a variety of hormones that are often referred to as trophic hormones. The term 'trophic' (from Greek trophos, meaning "to feed" or "nourish") signifies their role in stimulating the growth, development, and function of other endocrine glands or target tissues.

- High [Hormone]: A consistently high concentration of a trophic hormone typically causes its target organ to hypertrophy (increase in size) and often leads to hyperfunction (increased activity).

- Low [Hormone]: Conversely, a consistently low concentration of a trophic hormone can cause its target organ to atrophy (decrease in size) and often leads to hypofunction (decreased activity).

These hormones are essential for orchestrating a wide range of physiological processes.

Hormones and Their Characteristics:

While all anterior pituitary hormones are crucial, some share structural and functional similarities.

- Structurally and Functionally Related Group:

- Growth Hormone (GH)

- Prolactin (PRL)

- Human Placental Lactogen (hPL) (Note: hPL is produced by the placenta, not the anterior pituitary, but shares structural and functional similarities with GH and Prolactin).

- Similar Alpha Peptide Units (Glycoproteins): These hormones are glycoproteins consisting of two subunits: an alpha subunit and a beta subunit. The alpha subunit is virtually identical across this group, while the beta subunit is different and confers hormone-specific biological activity.

- Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH)

- Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH)

- Luteinizing Hormone (LH)

- Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) (Note: hCG is produced by the placenta, not the anterior pituitary, but is structurally similar to LH, FSH, and TSH).

The Seven Key Anterior Pituitary Hormones:

Let's look at the individual anterior pituitary hormones in more detail:

1. Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH), or Thyrotropin:

- Target Tissue: Primarily the thyroid gland (indirect).

- Function: Stimulates the thyroid gland to release thyroid hormones (T3 and T4).

- Regulation: Its production is influenced by stress (which can increase production) and, more importantly, by Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH) from the hypothalamus and negative feedback from thyroid hormones.

2. Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH), or Corticotropin:

- Target Tissue: The adrenal cortex.

- Function: Stimulates the release of steroid hormones by the adrenal glands. Specifically targets cells producing glucocorticoids (like cortisol), which affect glucose metabolism, stress response, and immune function.

- Regulation: Heavily influenced by stress (which increases its production) and by Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus.

3. Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH):

- Target Tissue: The gonads (ovaries in females, testes in males).

- Function (Females): Promotes egg development within ovarian follicles and stimulates the secretion of estrogens by ovarian cells.

- Function (Males): Supports sperm production (spermatogenesis) in the testes.

- Regulation: Regulated by Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus and negative feedback from gonadal steroids.

4. Luteinizing Hormone (LH):

- Target Tissue: The gonads (ovaries in females, testes in males).

- Function (Females): Induces ovulation (the release of a mature egg from the ovary) and promotes the ovarian secretion of estrogens and progesterone, which prepare the body for the possibility of pregnancy.

- Function (Males): Stimulates the interstitial cells (Leydig cells) in the testes to produce testosterone.

- Regulation: Regulated by Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus and negative feedback from gonadal steroids.

- Note: Both FSH and LH are collectively known as Gonadotropic Hormones because they target the gonads.

5. Prolactin (PRL):

- Target Tissue: Primarily breast tissue (mammary glands).

- Function (Females): Stimulates the development of the mammary glands and, crucially, the production of milk (lactogenesis) after childbirth.

- Function (Males): Historically thought to have no effect on human males, but recent research suggests roles in immune function, prostate health, and reproductive behavior, though not milk production.

- Regulation: Its release is primarily under tonic inhibition by Dopamine (Prolactin-Inhibiting Factor, PIF) from the hypothalamus. Mechanical stimulation of breast tissue (nursing) causes a rapid increase in prolactin production by inhibiting dopamine release. High levels of sex hormones (estrogens) can cause sensitivity of breast tissue prior to the flow phase of the menstrual cycle, and prolactin works with other hormones to stimulate breast development.

6. Growth Hormone (GH), or Somatotropin:

- Target Tissue: Nearly all body cells, especially bone, cartilage, and muscle.

- Function: Stimulates cell growth and replication primarily by increasing the rate of protein synthesis. It also has metabolic effects: it promotes the breakdown of fat (lipolysis) and causes the liver to break down glycogen reserves, releasing glucose into the circulation, thus raising blood glucose levels (diabetogenic effect). Its growth-promoting effects are largely mediated by insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) produced by the liver and other tissues.

- Regulation: Regulated by Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH) and Somatostatin (GHIH) from the hypothalamus.

- Disorders of GH Secretion:

- Hyposecretion (too little GH):

- Children: Leads to pituitary dwarfism (or growth hormone deficiency). Affected individuals have normal body proportions but are usually no taller than 4 feet tall.

- Adults: Can lead to Simmond's disease, characterized by atrophy and premature aging, loss of lean body mass, and increased fat mass.

- Hypersecretion (too much GH):

- Children: Leads to pituitary gigantism, where individuals grow to extreme heights (8-9 feet tall) with generally normal body proportions.

- Adults: Leads to acromegaly, a condition characterized by:

- Widened bones and thick fingers/toes.

- Lengthening of the jaw and cheekbones.

- Thickened eyelids, lips, tongue, and nose.

- Enlargement of internal organs.

- Hyposecretion (too little GH):

7. Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone (MSH):

- Target Tissue: The melanocytes in the epidermis (basal cell layer of the skin).

- Function: Stimulates the melanocytes of the skin, increasing their production of melanin, the pigment responsible for skin and hair color.

- Role in Humans: While very important in the control of skin and hair pigmentation in many animals, its physiological role in healthy adult humans is less clear. It is often released from the same precursor as ACTH. High levels are associated with certain conditions causing hyperpigmentation.

FEEDBACK CONTROL OF THE ANTERIOR PITUITARY

The secretion of anterior pituitary hormones is tightly regulated by negative feedback inhibition, primarily from the hormones secreted by their target glands. This ensures that hormone levels remain within a healthy physiological range.

Two Levels of Negative Feedback:

- Feedback at the Hypothalamus: The hormones secreted by the target glands (e.g., thyroid hormones, cortisol, gonadal steroids) can act directly on the hypothalamus to inhibit the secretion of its releasing hormones. For example, high thyroid hormone levels inhibit TRH release.

- Feedback at the Anterior Pituitary: The target gland hormones can also act directly on the anterior pituitary to inhibit its response to the hypothalamic releasing hormone, thereby reducing the secretion of the trophic hormone. For example, high thyroid hormone levels inhibit the pituitary's response to TRH.

POSTERIOR PITUITARY HORMONES

As discussed, the posterior pituitary does not synthesize hormones but stores and releases two neurohormones produced by the hypothalamus:

1. Antidiuretic Hormone (ADH), or Vasopressin:

- Synthesis Site: Primarily the supraoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus.

- Function:

- Antidiuretic Effect: Its primary role is to conserve water during urine formation by the kidney nephrons. It increases the permeability of the renal collecting ducts to water, allowing more water to be reabsorbed back into the bloodstream, thus reducing urine volume and concentrating the urine.

- Vasopressor Effect: At high concentrations (e.g., during severe hemorrhage), ADH also causes contraction of arteriolar smooth muscle, leading to vasoconstriction and an increase in blood pressure (hence the name vasopressin).

- Regulation: Released in response to increased plasma osmolality (too concentrated blood) or decreased blood volume/pressure.

2. Oxytocin:

- Synthesis Site: Primarily the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus.

- Function:

- Uterine Contraction: Stimulates the powerful contraction of uterine smooth muscle during childbirth, helping to expel the infant. Its release is stimulated by stretching of the cervix (Ferguson reflex).

- Milk Ejection (Let-down Reflex): Promotes the ejection (let-down) of milk from the mammary glands during breast-feeding in response to suckling. It contracts myoepithelial cells surrounding milk ducts.

- Social Bonding: Often referred to as the "love hormone" or "bonding hormone." It plays roles in social recognition, pair bonding, maternal-infant bonding, and other social behaviors.

These two hormones, though produced in the hypothalamus, are indispensable functions carried out by the posterior pituitary.

Source: https://doctorsrevisionuganda.com | Whatsapp: 0726113908

Hypothalamus & Pituitary Quiz

Systems Physiology

Enter your details to begin the examination.

🛡️ Privacy Note: Results are for tracking and certification purposes only.

Hypothalamus & Pituitary Quiz

Systems Physiology

Preparing questions...

Exam Completed!

See your performance breakdown below.