Growth Hormone Physiology

GROWTH HORMONE (SOMATOTROPHIN)

Growth Hormone (GH), also known as Somatotrophin, is a crucial hormone responsible for the growth and development of the body's tissues.

- Structure: It is a relatively small protein molecule, composed of a single chain of 191 amino acids, with a molecular weight of approximately 22,005.

- Half-Life: In the bloodstream, GH has a relatively short half-life of less than 20 minutes. This is because it binds only weakly to plasma proteins, allowing for rapid turnover.

- Primary Function: GH causes the growth of almost all tissues of the body that are capable of growing.

- It promotes an increase in the sizes of cells (hypertrophy) and an increase in mitosis (cell division), leading to the development of greater numbers of cells (hyperplasia).

- It also contributes to the specific differentiation of certain types of cells, such as bone growth cells (chondrocytes and osteoblasts) and early muscle cells (myoblasts).

- Mechanism of Action: In contrast to many other hormones that act through specific target glands (e.g., TSH acting on the thyroid), GH is unique because it does not function through a single target gland. Instead, it exerts its effects directly on all or almost all tissues of the body, acting as a widespread metabolic hormone.

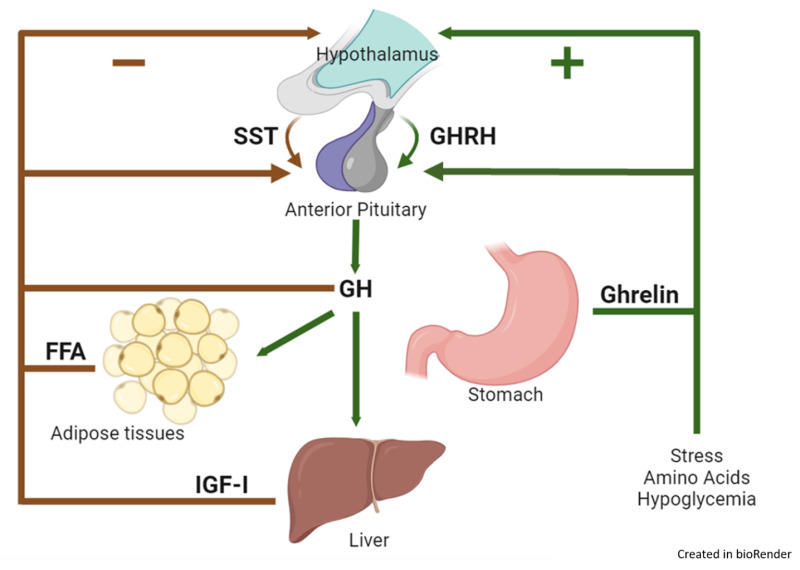

ROLE OF HYPOTHALAMUS IN SECRETION OF GROWTH HORMONE

The secretion of Growth Hormone from the anterior pituitary gland is meticulously controlled by the hypothalamus through a dual regulatory system involving both stimulating and inhibiting hormones.

- Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH):

- The hypothalamus secretes Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH).

- GHRH is a peptide hormone that travels through the hypophyseal portal system to the anterior pituitary gland.

- Upon reaching the anterior pituitary, GHRH acts on the somatotrophs (GH-secreting cells) to stimulate the release of Growth Hormone.

- Growth Hormone-Inhibitory Hormone (GHIH) / Somatostatin:

- When growth hormone levels in the blood rise above a certain normal threshold, or in response to other physiological cues, the hypothalamus releases Somatostatin, also known as Growth Hormone-Inhibitory Hormone (GHIH).

- Somatostatin also travels to the anterior pituitary via the portal system.

- There, it acts on the somatotrophs to inhibit the release of Growth Hormone. This provides a crucial negative feedback mechanism to prevent excessive GH secretion.

REGULATION OF GROWTH HORMONE SECRETION: FACTORS THAT STIMULATE OR INHIBIT

The secretion of Growth Hormone is complex and pulsatile, influenced by a variety of physiological, metabolic, and hormonal factors, operating through the hypothalamic GHRH and GHIH system.

Factors That Stimulate Growth Hormone Secretion:

These factors generally indicate a need for energy mobilization, tissue repair, or active growth.

- Decreased Blood Glucose (Hypoglycemia): A fall in blood sugar is a potent stimulus for GH release, helping to mobilize glucose from the liver.

- Decreased Blood Free Fatty Acids: Low levels of free fatty acids also stimulate GH secretion, as GH promotes fat breakdown.

- Starvation or Fasting, Protein Deficiency: These states signal a need for metabolic adaptation, with GH promoting protein conservation and fat utilization.

- Trauma, Stress, Excitement: Acute stress (physical or psychological) can trigger GH release, potentially aiding in recovery and energy mobilization.

- Exercise: Physical activity is a strong stimulus for GH secretion, contributing to muscle repair and growth.

- Hormones (Testosterone, Estrogen): Sex hormones, particularly during puberty, contribute to growth spurts and stimulate GH secretion.

- Deep Sleep (Stages II and IV): The majority of daily GH secretion occurs in bursts during the early stages of deep sleep, highlighting its role in growth and repair.

- Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH): As mentioned, this hypothalamic hormone is the primary physiological stimulator of GH release.

Factors That Inhibit Growth Hormone Secretion:

These factors typically signal sufficient energy stores or act as part of a negative feedback loop to prevent overproduction.

- Increased Blood Glucose (Hyperglycemia): High blood sugar levels inhibit GH release, as there is no immediate need to mobilize more glucose.

- Increased Blood Free Fatty Acids: Abundant free fatty acids indicate sufficient energy stores, suppressing GH secretion.

- Aging: As individuals age, basal and stimulated GH secretion generally decline, contributing to some of the metabolic changes associated with aging.

- Obesity: Obese individuals often exhibit lower GH secretion, which may contribute to their metabolic profile.

- Growth Hormone Inhibitory Hormone (GHIH) / Somatostatin: This hypothalamic hormone is the primary physiological inhibitor of GH release.

- Growth Hormone (Exogenous): Administration of exogenous GH provides a negative feedback signal to the hypothalamus and pituitary, inhibiting endogenous GH secretion.

- Somatomedins (Insulin-like Growth Factors - IGFs): These are peptide hormones, primarily IGF-1, produced largely by the liver in response to GH. IGFs act as a crucial negative feedback signal, directly inhibiting GH release from the pituitary and also stimulating GHIH release from the hypothalamus.

PHYSIOLOGICAL FUNCTIONS OF GROWTH HORMONE

As established, Growth Hormone (GH) is unique in that it does not function through a single target gland but rather exerts its pervasive effects directly on all or almost all tissues of the body that are capable of growing. Its diverse actions can be broadly categorized into:

- Promotes growth of many tissues: This is its most prominent and well-known function.

- Enhances fat utilization for energy: Shifting the body's fuel source.

- Decreases carbohydrate utilization: Conserving glucose, which has implications for blood sugar.

- Promotes protein deposition in tissues: Essential for tissue repair and growth.

GH PROMOTES PROTEIN DEPOSITION IN TISSUES

Growth Hormone is a potent anabolic hormone, meaning it promotes the building up of complex molecules from simpler ones, particularly proteins. While the precise mechanisms are still being fully elucidated, several key effects are known:

- Increased Nuclear Transcription of DNA to form RNA: GH stimulates the machinery within the cell nucleus to increase the transcription of DNA into various types of RNA (mRNA, tRNA, rRNA). This effectively ramps up the production of the templates and components necessary for protein synthesis.

- Enhancement of Amino Acid Transport Through the Cell Membranes: GH increases the active transport of amino acids from the extracellular fluid into the cells. This ensures a readily available supply of the building blocks for protein synthesis within the cells.

- Enhancement of RNA Translation to Cause Protein Synthesis by the Ribosomes: Once inside the cell, GH further promotes the translation of RNA into protein by the ribosomes. This means that not only are more protein blueprints being made, but they are also being utilized more efficiently to produce actual proteins.

- Decreased Catabolism of Protein and Amino Acids: Beyond promoting synthesis, GH also reduces the breakdown (catabolism) of existing proteins and amino acids. This dual action—increasing synthesis and decreasing breakdown—maximizes protein accumulation in tissues.

In summary: GH enhances almost all facets of amino acid uptake and protein synthesis by cells, while at the same time reducing the breakdown of proteins. This collective action leads to a positive nitrogen balance and overall tissue growth.

GH ENHANCES FAT UTILIZATION FOR ENERGY

One of the significant metabolic effects of GH is its ability to shift the body's primary fuel source away from carbohydrates and proteins and towards fats.

- Release of Fatty Acids from Adipose Tissue: GH directly stimulates adipose tissue (fat cells) to release fatty acids into the bloodstream. This significantly increases the concentration of free fatty acids in the body fluids.

- Enhanced Conversion to Acetyl Coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA): These increased free fatty acids are then readily taken up by cells, where they are converted into acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) through beta-oxidation. Acetyl-CoA is a central molecule in energy metabolism, entering the Krebs cycle for subsequent utilization to produce ATP (energy).

- Preference for Fat as Fuel: The consequence of this is that fat is used for energy in preference to the use of carbohydrates and proteins. This "protein-sparing" effect is crucial during periods of growth or when nutrient intake is limited, allowing proteins to be used for structural purposes and growth rather than for energy. This overall leads to an increase in lean body mass.

However, there are potential downsides:

- Ketosis: Sometimes, the mobilization of fat from adipose tissue can be so rapid and extensive that the liver processes large quantities of fatty acids into acetyl-CoA, exceeding the capacity of the Krebs cycle. This leads to the excessive formation and release of acetoacetic acid and other ketone bodies into the body fluids, potentially causing ketosis.

- Fatty Liver: This excessive mobilization of fat from the adipose tissue can also frequently cause a fatty liver, as the liver takes up large amounts of fatty acids, which can accumulate if their oxidation or export is not balanced.

GH DECREASES CARBOHYDRATE UTILIZATION

GH has significant effects on carbohydrate metabolism, generally leading to an increase in blood glucose levels and earning it the label of a "diabetogenic" hormone. Several effects contribute to this:

- Decreased Glucose Uptake in Tissues: GH reduces the uptake of glucose by peripheral tissues, such as skeletal muscle and fat cells. This means that these cells rely more on fatty acids for energy, leaving more glucose in the bloodstream.

- Increased Glucose Production by the Liver: GH stimulates the liver to increase its output of glucose, primarily through gluconeogenesis (synthesis of glucose from non-carbohydrate precursors) and possibly glycogenolysis (breakdown of glycogen).

- Increased Insulin Secretion: As a consequence of the rising blood glucose levels, the pancreas is stimulated to increase insulin secretion in an attempt to normalize blood sugar.

Mechanism: GH-induced "Insulin Resistance": Each of these changes results from GH-induced "insulin resistance," which attenuates the action of insulin. This means that cells become less responsive to insulin's signals to take up glucose. The overall outcome is an increased blood glucose concentration and a compensatory increase in insulin secretion. This mirrors the characteristics of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), hence GH is said to have diabetogenic effects.

Unclear Mechanisms: The precise mechanisms of this insulin resistance are still unclear, but it may be attributed to increased blood concentrations of fatty acids. Elevated fatty acids can interfere with insulin signaling pathways in various tissues.

GH STIMULATES CARTILAGE AND BONE GROWTH

This is perhaps the most obvious and defining effect of Growth Hormone, particularly during childhood and adolescence. Several interconnected effects contribute to this:

- Increased Deposition of Protein by Chondrocytic and Osteogenic Cells: GH stimulates chondrocytes (cartilage cells) and osteogenic cells (bone-forming cells) to increase the synthesis and deposition of protein, especially collagen, which forms the organic matrix of cartilage and bone.

- Increased Rate of Reproduction of These Cells: GH promotes the proliferation (mitosis) of both chondrocytes and osteogenic cells. This leads to an increased number of cells actively involved in growth.

- Specific Effect of Converting Chondrocytes into Osteogenic Cells: GH also plays a role in the differentiation of chondrocytes into osteogenic cells. This conversion is crucial in the process of endochondral ossification, where cartilage is replaced by bone.

Two main mechanisms govern bone growth under GH influence:

- Stimulation of Long Bones to Grow in Length at the Epiphyseal Cartilages:

- In growing individuals, the long bones (e.g., femur, tibia) grow in length at the epiphyseal growth plates (cartilages), which are located at the ends of the bone, separating the epiphyses from the shaft.

- GH directly stimulates the chondrocytes within these growth plates to proliferate and enlarge, pushing the epiphyses further from the diaphysis. Subsequently, this cartilage is calcified and replaced by bone, leading to an increase in bone length. This process continues until the growth plates fuse after puberty, at which point longitudinal growth ceases.

- Stimulation of Osteoblasts (Deposition of New Bone):

- GH strongly stimulates osteoblasts, the cells responsible for depositing new bone. This leads to an increase in bone thickness and density, especially in membranous bones (e.g., skull bones, jawbone).

- In this context, osteoblast activity is stimulated to be greater than osteoclast activity, resulting in a net increase in bone mass.

GH AND THE ROLE OF SOMATOMEDINS (INSULIN-LIKE GROWTH FACTORS - IGFs)

While GH has direct effects on tissues, many of its growth-promoting actions are mediated indirectly through a group of small proteins called somatomedins, now more commonly known as Insulin-like Growth Factors (IGFs).

- Formation: GH causes the liver (and, to a much lesser extent, other tissues like cartilage) to form these somatomedins.

- Potent Effect on Growth: These somatomedins have a potent effect of increasing all aspects of bone growth and general tissue growth.

- "Insulin-like" Activity: Their effects on growth are very similar to those of insulin, hence the name Insulin-like Growth Factors.

- Types of Somatomedins: Four main types have been isolated, but somatomedin C is the most potent and clinically significant, often referred to as IGF-I.

- Somatomedin C (IGF-I):

- It has a molecular weight of about 7500.

- Its concentration in the plasma closely follows the rate of growth hormone secretion, making it a good clinical indicator of GH activity.

- Binding to Carrier Proteins: A critical feature of Somatomedin C is that it attaches strongly to specific carrier proteins in the blood. This binding has several important consequences:

- Prolonged Half-Life: It is released only slowly from the blood to the tissues, with a significantly longer half-life time of about 20 hours (compared to GH's <20 minutes).

- Sustained Growth-Promoting Effects: This greatly prolongs the growth-promoting effects of the pulsatile bursts of GH, providing a more continuous stimulus for tissue growth.

- Unclear Details: While the role of somatomedins/IGFs in mediating GH's actions is well-established, the precise details of their interaction and regulation are still areas of active research. It's understood that GH primarily stimulates IGF-I production, and IGF-I then carries out many of the anabolic and growth-promoting effects attributed to GH.

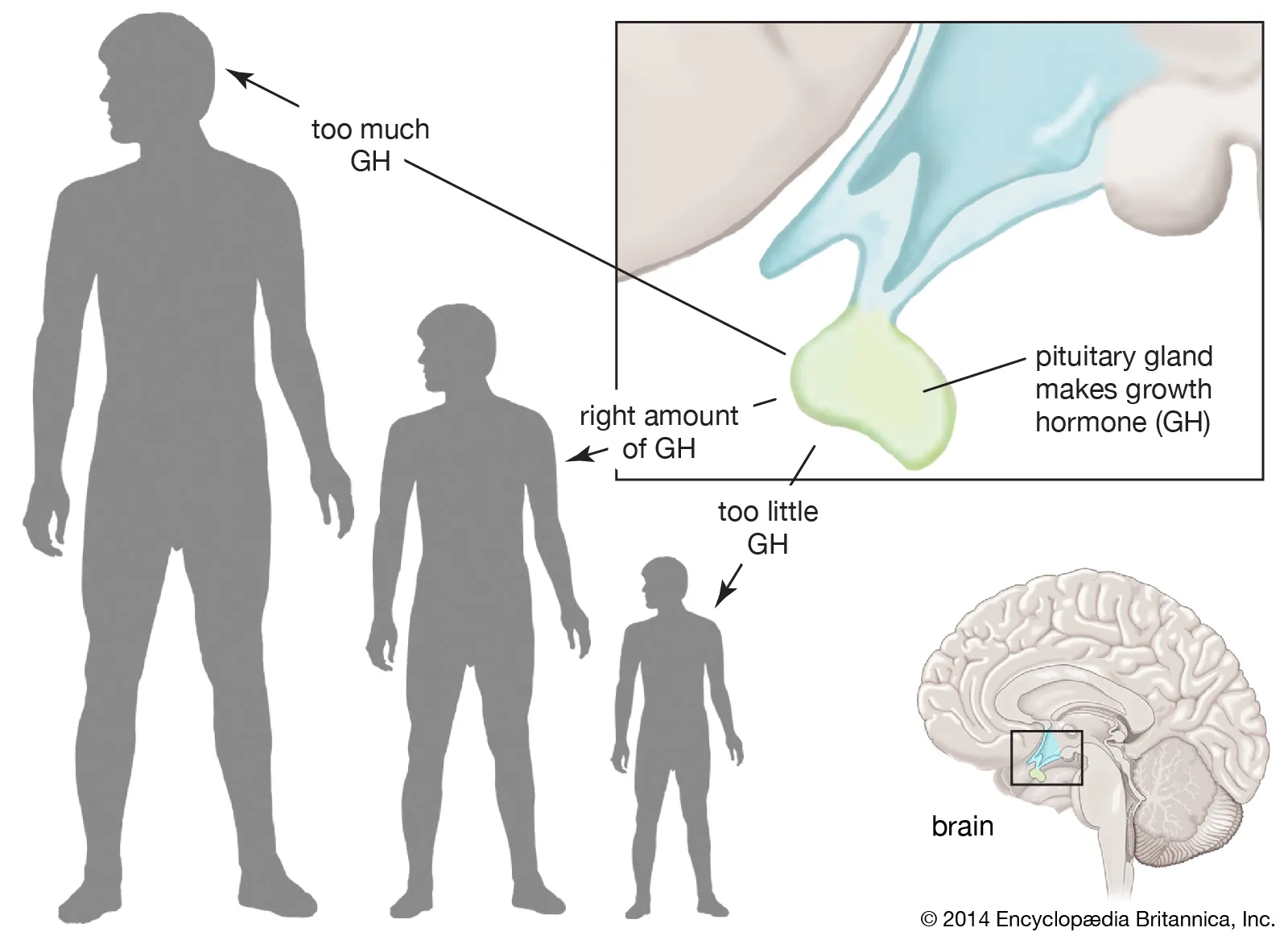

ABNORMALITIES OF GROWTH HORMONE SECRETION

Disruptions in the normal production or action of Growth Hormone (GH) can lead to a variety of clinical syndromes, ranging from stunted growth to excessive growth and metabolic disturbances. These abnormalities highlight the critical role GH plays throughout life. We will discuss four main conditions:

- Panhypopituitarism

- Dwarfism

- Gigantism

- Acromegaly

PANHYPOPITUITARISM

Panhypopituitarism refers to a condition characterized by decreased secretion of all or almost all the anterior pituitary hormones. This global deficiency impacts not just Growth Hormone but also TSH, ACTH, FSH, LH, and prolactin, leading to widespread endocrine dysfunction.

- Onset: This decrease in pituitary hormone secretion can be congenital (present from birth) or may develop suddenly or slowly at any time during life. The clinical manifestations will vary depending on the age of onset and the severity of the deficiency.

- Etiology (Causes):

- Pituitary Tumors: The most common cause in adults is a pituitary tumor (e.g., a non-functional adenoma) that grows and compresses or destroys the normal pituitary gland tissue.

- Craniopharyngiomas: In children, tumors like craniopharyngiomas can cause similar widespread pituitary dysfunction.

- Infarction: Ischemic necrosis of the pituitary, such as Sheehan's syndrome (postpartum pituitary necrosis due to severe hemorrhage and hypovolemia during childbirth), is another cause.

- Trauma, Radiation, Surgery: Head trauma, radiation therapy to the head, or surgery involving the pituitary region can also damage the gland.

- Infiltrative Diseases: Conditions like sarcoidosis or hemochromatosis can infiltrate and damage pituitary tissue.

- Genetic Mutations: Rare genetic mutations affecting pituitary development can lead to congenital panhypopituitarism.

- Clinical Manifestations (if GH is affected):

- Children: If panhypopituitarism occurs during childhood, it will lead to dwarfism (as discussed below), along with delayed puberty, hypothyroidism, and adrenal insufficiency.

- Adults: In adults, symptoms include hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, hypogonadism, and often subtle signs of GH deficiency, such as reduced muscle mass, increased central adiposity, and fatigue.

DWARFISM

Dwarfism specifically refers to significantly stunted growth and short stature, often resulting from a deficiency in Growth Hormone.

- Etiology: It is mostly due to a generalized deficiency of anterior pituitary secretion during childhood, which implies that not only GH but often other pituitary hormones (leading to varying degrees of panhypopituitarism) are also deficient.

- GH Deficiency: The most direct cause is an insufficient secretion of GH itself, often due to a pituitary lesion, genetic factors, or idiopathic reasons.

- GHRH Deficiency: Problems with hypothalamic GHRH production can also lead to secondary GH deficiency.

- GH Insensitivity (Laron Syndrome): In some cases, the problem isn't a lack of GH, but rather that the body's tissues are unresponsive to GH. This is due to defects in the GH receptor, leading to a failure to produce IGF-I.

- Clinical Features:

- Proportional Development: Despite their short stature, individuals with pituitary dwarfism generally exhibit all the body physical parts developing in appropriate proportion to one another. They are essentially miniature adults.

- Slow Growth Rate: Their growth rate is significantly slowed. For example, a child who has reached the age of 10 years may have the bodily development and size of a child aged 4 to 5 years. Similarly, a person at age 20 years might have the bodily development of a child aged 7 to 10 years.

- Sexual Maturity: Unless treated, individuals with generalized panhypopituitarism may also have delayed or absent sexual development due to deficiencies in gonadotropins (FSH and LH).

- Mental Development: Importantly, mental development is typically normal, distinguishing them from other forms of dwarfism (e.g., cretinism due to severe hypothyroidism).

- Specific Forms of Dwarfism:

- African Pygmies and Levi-Lorain Dwarfs: In these genetically distinct groups, the rate of growth hormone secretion is often normal or even high. However, the underlying issue is a hereditary inability to form Somatomedin C (IGF-I), which is a key step for the promotion of growth by growth hormone. Their tissues are insensitive to GH due to a defect in the GH receptor or post-receptor signaling, leading to a lack of IGF-I, which is the primary mediator of GH's growth-promoting effects.

GIGANTISM

Gigantism is a condition characterized by excessive growth and abnormally tall stature, resulting from overproduction of Growth Hormone during childhood or adolescence.

- Etiology: Gigantism is typically caused by an acidophilic tumor (adenoma) of the anterior pituitary gland, which secretes large quantities of Growth Hormone. These tumors are often composed of somatotroph cells.

- Timing is Key: The critical factor differentiating gigantism from acromegaly is that the condition occurs before adolescence, specifically before the epiphyses of the long bones have become fused with the shafts.

- Clinical Features:

- Rapid and Excessive Growth: All body tissues grow rapidly, including the bones, leading to an extreme increase in height. Individuals can become exceptionally tall, often reaching heights of up to 8 feet.

- Proportional Growth (initially): While overall size is exaggerated, the body proportions generally remain relatively normal in the early stages, although later stages may show some disproportion.

- Metabolic Complications:

- Hyperglycemia and Diabetes Mellitus: Giants are often hyperglycemic due to the anti-insulin effects of excessive GH. This chronic strain on the pancreatic beta cells can lead to their degeneration, eventually resulting in diabetes mellitus in a significant percentage of these individuals.

- Weakness: Despite their large size, individuals with gigantism often experience generalized body weakness, likely due to the catabolic effects of very high GH levels on muscles and other tissues, or related to the metabolic burden.

- Cardiovascular Issues: Enlargement of organs and increased metabolic demand can strain the cardiovascular system, leading to heart failure over time.

- Treatment: Once gigantism is diagnosed, further effects can often be blocked by:

- Microsurgical Removal of the Tumor: This is the primary and most effective treatment to remove the source of excess GH.

- Irradiation of the Pituitary Gland: Radiation therapy can be used as an alternative or adjuvant treatment, particularly if surgery is not feasible or not completely successful.

- Pharmacological Agents: Medications like somatostatin analogues (which inhibit GH release) or GH receptor antagonists can also be used to control GH levels.

ACROMEGALY

Acromegaly is a condition resulting from the overproduction of Growth Hormone, similar to gigantism, but it occurs after adolescence.

- Etiology: Like gigantism, acromegaly is almost invariably caused by an acidophilic tumor (adenoma) of the anterior pituitary gland that secretes excessive GH.

- Timing is Key: The crucial distinction is that this excessive GH secretion occurs after the epiphyses of the long bones have fused with the shaft. Once the growth plates are closed, longitudinal bone growth is no longer possible.

- Clinical Features (Growth of Bones and Soft Tissues):

- No Increase in Height: The person cannot grow taller.

- Thickening of Bones: Instead, the bones become thicker and denser, particularly in the extremities and membranous bones.

- Soft Tissue Growth: The soft tissues throughout the body continue to grow and proliferate.

- Characteristic Enlargement Patterns:

- Hands and Feet: Enlargement is most marked in the bones of the hands and feet, making them appear broad and large. Patients often report needing larger shoe and ring sizes. The fingers become extremely thickened, often described as "spade-like" (hands can be up to twofold normal size).

- Face and Skull: Significant changes occur in the membranous bones of the skull. This includes:

- Protrusion of the Lower Jaw (Prognathism): The lower jawbone (mandible) grows forward, often by half an inch or more, creating a characteristic prognathic appearance.

- Enlarged Nose: The nose increases significantly in size, sometimes up to twice its normal size.

- Prominent Forehead and Supraorbital Ridges: The forehead slants forward, and the bony ridges above the eyes (supraorbital ridges) become very prominent, creating a heavy brow.

- Bosses on the Forehead: Bony protuberances develop on the forehead.

- Increased Skull Thickness: The cranium generally thickens.

- Spine: Growth of portions of the vertebrae can lead to an exaggerated outward curvature of the thoracic spine, known as kyphosis (hunchback).

- Organomegaly: Internal organs also undergo significant enlargement. The tongue (macroglossia), the liver (hepatomegaly), and especially the kidneys become greatly enlarged.

- Other Soft Tissue Changes: Skin thickens and becomes oily, hair growth may increase, and vocal cords thicken, leading to a deeper voice.

- Metabolic and Systemic Effects: Similar to gigantism, patients with acromegaly also experience:

- Hyperglycemia and Diabetes Mellitus: Due to chronic GH excess causing insulin resistance.

- Cardiovascular Disease: Hypertension, cardiomyopathy, and an increased risk of heart failure.

- Arthritis: Due to joint overgrowth and degeneration.

- Headaches and Visual Field Defects: From the growing pituitary tumor compressing surrounding structures.

- Diagnosis and Treatment: Diagnosis involves measuring elevated GH and IGF-I levels, along with imaging (MRI) of the pituitary gland. Treatment strategies are similar to gigantism:

- Transsphenoidal Surgery: Surgical removal of the pituitary adenoma is the first-line treatment.

- Radiation Therapy: Used as an adjunct or alternative.

- Pharmacological Agents: Somatostatin analogues, GH receptor antagonists, and dopamine agonists are used to control GH and IGF-I levels.

Growth Hormone Quiz

Systems Physiology

Enter your details to begin the examination.

🛡️ Privacy Note: Results are for tracking and certification purposes only.

Growth Hormone Quiz

Systems Physiology

Preparing questions...

Exam Completed!

See your performance breakdown below.