Digestive/GIT Neuro & Motility

The Digestive System Physiology

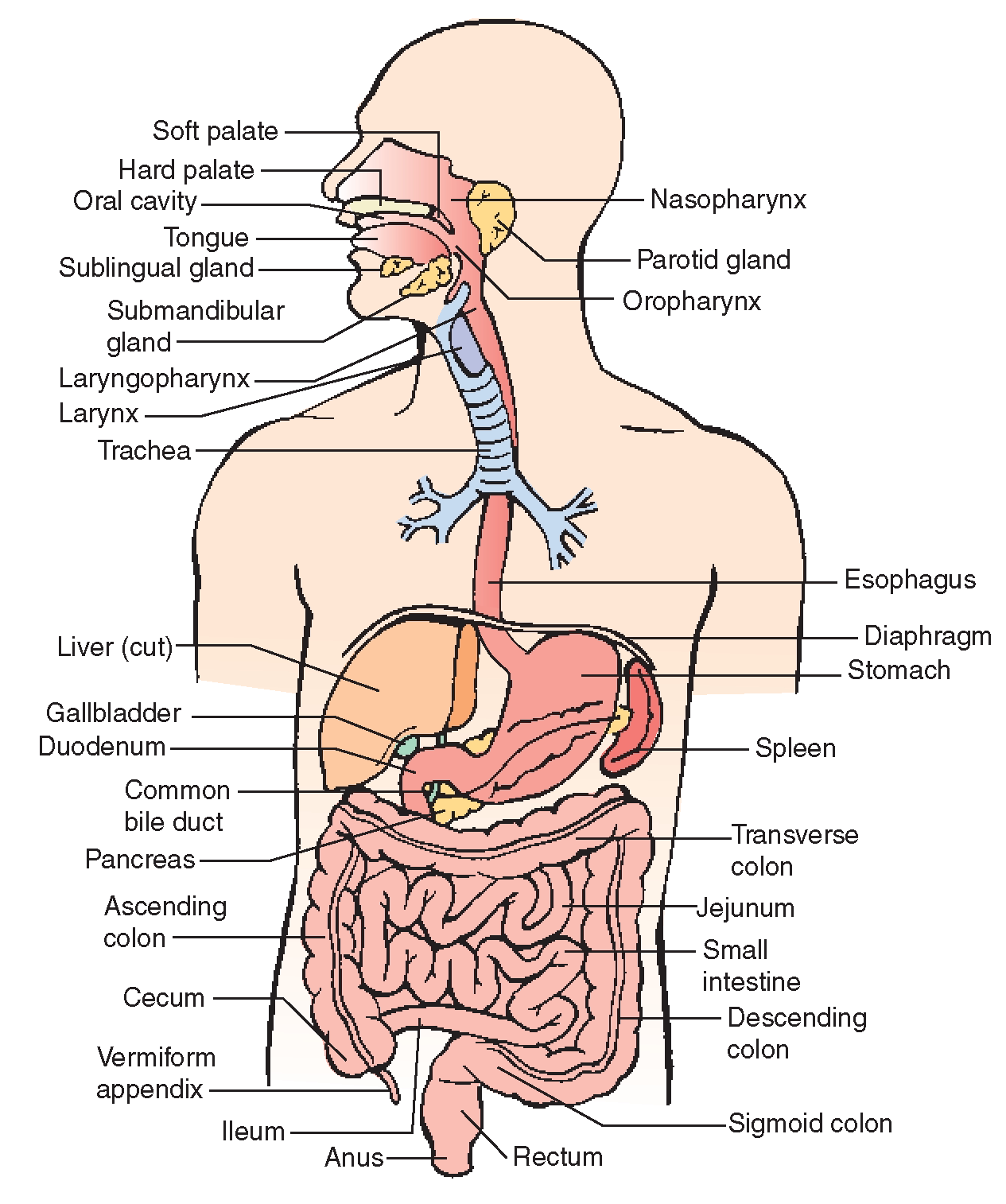

The digestive system is a vital organ system responsible for breaking down food into absorbable nutrients, water, and electrolytes, and then eliminating indigestible waste. It can be broadly divided into two main parts: the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), also known as the alimentary canal or gut, and accessory digestive organs.

I. Components of the Digestive System

A. The Gastrointestinal Tract (GIT) / Alimentary Canal

This is a continuous, muscular tube that extends from the mouth to the anus, about 30 feet (9 meters) long in a cadaver (shorter in a living person due to muscle tone). It is the primary site where digestion and absorption occur.

- Mouth: The entrance, where mechanical digestion (chewing) and initial chemical digestion (salivary enzymes) begin.

- Pharynx: A common passageway for food and air.

- Esophagus: A muscular tube that transports food from the pharynx to the stomach via peristalsis.

- Stomach: A muscular sac for food storage, mechanical churning, and initiation of protein digestion.

- Small Intestine: The primary site for chemical digestion and nutrient absorption. It's divided into the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum.

- Large Intestine (Colon): Primarily involved in water and electrolyte absorption, and formation/storage of feces.

B. Accessory Digestive Organs

These organs produce secretions that aid in digestion or help with the mechanical breakdown of food, but food does not pass directly through them.

- Teeth: Mechanically break down food (mastication).

- Tongue: Aids in tasting, chewing, and swallowing food.

- Salivary Glands (parotid, submandibular, sublingual): Produce saliva, containing enzymes (e.g., amylase for starch) and mucus.

- Liver: Produces bile (important for fat digestion), metabolizes nutrients, and detoxifies.

- Gallbladder: Stores and concentrates bile produced by the liver.

- Pancreas (exocrine part): Produces a wide range of digestive enzymes (for carbohydrates, proteins, fats) and bicarbonate to neutralize stomach acid.

II. Key Roles of the GIT

The primary function of the GIT is to provide the body with essential water, electrolytes, and nutrients. To achieve this, it performs six fundamental processes:

- Ingestion: Taking food into the digestive tract, typically through the mouth.

- Propulsion (Movement of Food): Moving food through the alimentary canal, which includes:

- Swallowing (Deglutition): Voluntary and involuntary.

- Peristalsis: Rhythmic waves of contraction and relaxation of smooth muscle in the organ walls, pushing food forward.

- Mechanical Digestion: Physical breakdown of food into smaller pieces to increase surface area for enzyme action. This includes chewing (mastication), churning in the stomach, and segmentation in the small intestine.

- Chemical Digestion: Enzymatic breakdown of complex food molecules into their simpler chemical building blocks (e.g., carbohydrates into monosaccharides, proteins into amino acids, fats into fatty acids and glycerol).

- Absorption: The passage of digested nutrients, vitamins, minerals, and water from the lumen of the GIT into the blood or lymph.

- Defecation: Elimination of indigestible substances and waste products from the body in the form of feces.

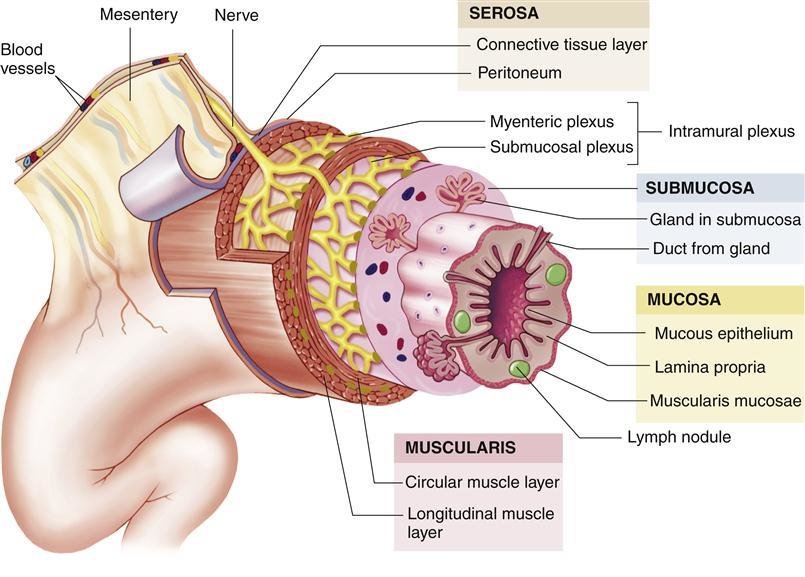

III. Structure of the GIT Wall (The Four Tunics)

The wall of the GIT from the esophagus to the anal canal has a consistent pattern of four distinct layers, or tunics, from the innermost to the outermost:

- Mucosa (Innermost Layer):

- Epithelium: Lines the lumen, specialized for secretion of mucus, digestive enzymes, and hormones, and for absorption of digested nutrients. Protects against disease.

- Lamina Propria: Loose connective tissue with capillaries (for absorption) and lymphoid follicles (MALT - mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, for defense).

- Muscularis Mucosae: A thin layer of smooth muscle that produces local movements of the mucosa, facilitating absorption and secretion.

- Submucosa:

- Dense connective tissue containing blood and lymphatic vessels, lymphoid follicles, and nerve fibers (submucosal plexus/Meissner's plexus). These nerves help regulate glands and smooth muscle in the mucosa.

- Muscularis Externa (Muscularis):

- Responsible for segmentation and peristalsis.

- Typically consists of two layers of smooth muscle:

- Inner Circular Layer: Fibers run around the circumference of the organ. Contraction constricts the lumen.

- Outer Longitudinal Layer: Fibers run parallel to the long axis of the organ. Contraction shortens the organ.

- An additional oblique muscle layer is found only in the stomach, aiding in its powerful churning action.

- Contains the myenteric plexus (Auerbach's plexus) between the two muscle layers, which controls GIT motility.

- Serosa (Outermost Layer):

- The protective outermost layer, which is the visceral peritoneum in most parts of the alimentary canal. It is a thin layer of areolar connective tissue covered with mesothelium.

- In the esophagus, the outermost layer is an adventitia (fibrous connective tissue) instead of serosa.

IV. Smooth Muscles of the GIT and Electrical Activity

The smooth muscle of the muscularis externa is crucial for the motor functions of the GIT.

A. Characteristics of GI Smooth Muscle:

- Individual fibers are small (200-500 µm long, 2-10 µm diameter).

- Arranged in bundles (up to 1000 fibers) separated by loose connective tissue.

- Functional Syncytium: Muscle fibers within a layer (and between layers) are electrically connected by gap junctions. This allows action potentials to spread rapidly from one fiber to the next, causing the entire muscle layer or bundle to contract as a single unit.

B. Electrical Activity:

The resting membrane potential (RMP) of GI smooth muscle is unstable and fluctuates, typically averaging around -56 mV. Two basic types of electrical waves characterize its activity:

1. Slow Waves (Basic Electrical Rhythm - BER)

- Not true action potentials. They are undulating, rhythmic fluctuations in the RMP, oscillating between -50 and -60 mV.

- Caused by pacemaker cells called Interstitial Cells of Cajal (ICCs), which act as electrical pacemakers.

- They set the maximum frequency of contraction.

- Slow waves themselves usually do not cause muscle contraction, except in some areas like the stomach where they might be strong enough. Their primary role is to set the stage for action potentials.

2. Spike Potentials (True Action Potentials)

- These are true action potentials that occur when the RMP of a slow wave depolarizes sufficiently (typically becoming less negative than -40 mV, reaching the threshold for excitation).

- The higher the peak of the slow wave rises above the threshold, the greater the frequency of spike potentials (1 to 10 spikes/second), leading to stronger and more prolonged muscle contraction.

- Ionic Basis: These action potentials are primarily caused by the influx of calcium ions (Ca²⁺), along with some sodium ions, through specialized voltage-gated calcium-sodium channels. The influx of Ca²⁺ directly triggers muscle contraction.

C. Smooth Muscle Contractions:

- Rhythmic Contractions (Phasic Contractions): Characterized by periodic contractions followed by relaxation.

- Examples: Peristaltic waves in the esophagus, gastric antrum, and small intestine (segmentation). These are generally associated with spike potentials.

- Tonic Contractions: Maintained contractions without relaxation, lasting for minutes to hours.

- Examples: In the orad (proximal) region of the stomach, lower esophageal sphincter, ileocecal valve, and internal anal sphincter.

- These contractions are not always associated with spike potentials and can sometimes be due to slow wave activity alone or sustained Ca²⁺ entry. They are crucial for maintaining pressure or acting as valves.

D. Factors Affecting the RMP and Excitability of GI Smooth Muscle:

The excitability of GI smooth muscle is highly regulated by various factors that alter its RMP:

- Factors that DEPOLARIZE the membrane (make it less negative, more excitable, closer to threshold):

- Stretching of the muscle: Mechanical stretch directly opens ion channels.

- Stimulation by acetylcholine (ACh): A key neurotransmitter.

- Parasympathetic nerve stimulation: Parasympathetic nerves release ACh at their endings.

- Specific gastrointestinal hormones: Certain hormones can increase excitability.

- Factors that HYPERPOLARIZE the membrane (make it more negative, less excitable, further from threshold):

- Norepinephrine (NE) or Epinephrine: Catecholamines.

- Sympathetic nerve stimulation: Sympathetic nerves primarily release NE at their endings (or activate adrenal epinephrine release).

Control of the Gastrointestinal Tract (GIT)

The functions of the Gastrointestinal Tract (GIT), including digestion, absorption, and motility, are regulated by both intrinsic (within the gut wall) and extrinsic (outside the gut wall) nervous systems, as well as by hormones and local factors. This comprehensive regulation ensures the precise coordination necessary for nutrient processing.

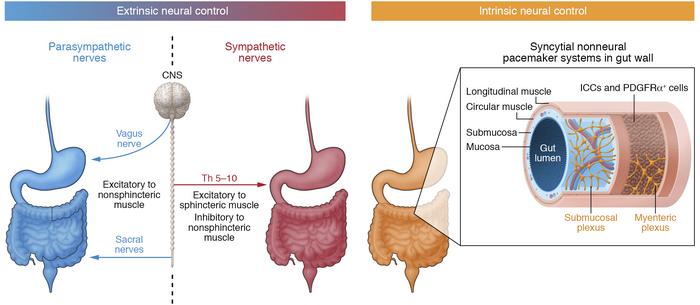

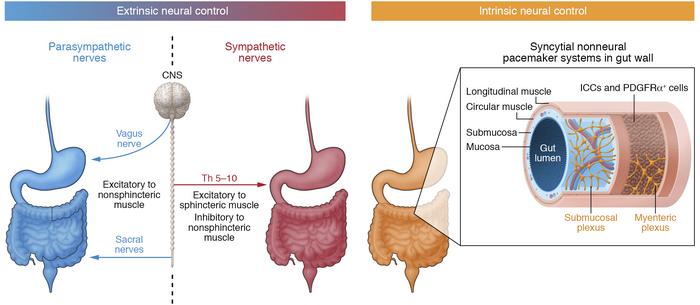

I. Innervation to the GIT

The GIT possesses a unique and extensive nervous system that allows it a significant degree of autonomy, while also being modulated by external influences. This innervation can be broadly categorized into intrinsic and extrinsic components.

A. Enteric Nervous System (ENS) - The "Brain of the Gut"

The ENS is often referred to as the "brain of the gut" due to its extensive network and ability to operate largely independently. It is the largest and most complex part of the nervous system outside of the brain and spinal cord.

- Location: The ENS lies entirely within the wall of the gut, extending from the esophagus all the way to the anus.

- Autonomy: It can function independently of the central nervous system (CNS), though its activity is significantly modulated by the CNS.

- Neurons: Contains approximately 100 million neurons, making it more extensive than the spinal cord.

- Primary Function: To control gastrointestinal movements (motility) and secretions.

Myenteric Plexus (Auerbach's Plexus)

- Location: Situated between the longitudinal and circular muscle layers of the muscularis externa.

- Structure: Consists mostly of a linear chain of many interconnecting neurons that extends the entire length of the GIT.

- Primary Control: Mainly controls GIT movements (motility), coordinating the contractions of the muscle layers.

- Principal Effects when Stimulated:

- Increased tonic contraction (or "tone") of the gut wall.

- Increased intensity of rhythmical contractions.

- Slightly increased rate of rhythmical contractions.

- Increased velocity of conduction of excitatory waves along the gut wall, leading to more rapid movement of peristaltic waves.

Submucosal Plexus (Meissner's Plexus)

- Location: Lies within the submucosa layer.

- Primary Control: Mainly concerned with controlling functions within the inner wall, specifically gastrointestinal secretion, local absorption, and local contraction of the muscularis mucosae, as well as local blood flow.

Neurotransmitters Secreted by the Enteric Nervous System:

The ENS utilizes a wide array of neurotransmitters, however, some key roles have been identified:

- Excitatory Motor Neurons: These evoke muscle contraction and intestinal secretion. Key neurotransmitters include Substance P and Acetylcholine (ACh).

- Secretomotor Neuron Neurotransmitters: These are responsible for releasing water, electrolytes, and mucus from crypts of Lieberkühn. Examples include ACh, Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP), and Histamine.

- Inhibitory Motor Neurons: These suppress muscle contraction. Key neurotransmitters include Nitric Oxide (NO), Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP), and Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP).

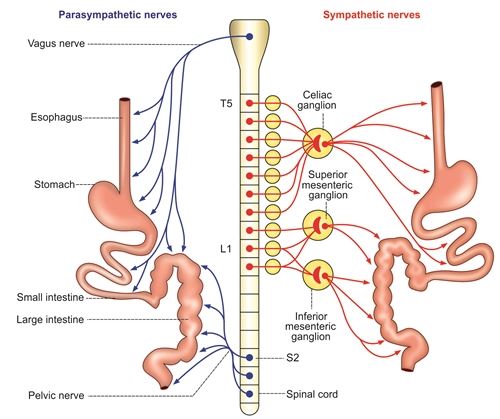

B. Extrinsic Nerve Supply (Autonomic Nervous System - ANS)

The ENS can function autonomously, but its activity is significantly modulated by extrinsic innervation from the ANS (parasympathetic and sympathetic systems).

- Overall Role: Extrinsic nerves do not initiate the basic rhythm of gut activity but can greatly enhance or inhibit existing gastrointestinal functions.

- Sensory Input: Sensory nerve endings originate in the gastrointestinal epithelium or gut wall. These send afferent fibers to:

- Both plexuses of the enteric system (for local reflexes).

- Prevertebral ganglia of the sympathetic nervous system.

- The spinal cord.

- The brain stem (via the vagus nerves).

Parasympathetic Nerve Fibers

- Neurotransmitter: Primarily Acetylcholine (ACh).

- Effect: Generally excitatory to GIT function.

- Accelerate movements: Increase motility (e.g., peristalsis).

- Increase secretions: Promote digestive gland activity.

- Pathways:

- Cranial Parasympathetics (Vagus Nerves): Supply the upper regions of the alimentary tract, including the mouth and pharyngeal regions, esophagus, stomach, and pancreas. They extend somewhat less to the intestines, down through the first half of the large intestine.

- Sacral Parasympathetics (Pelvic Nerves): Originate from the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th sacral segments of the spinal cord. They pass through the pelvic nerves to innervate the distal half of the large intestine and all the way to the anus. The sigmoidal, rectal, and anal regions are considerably better supplied with parasympathetic fibers than other intestinal areas, highlighting their critical role in defecation reflexes.

Sympathetic Nerve Fibers

- Neurotransmitter: Primarily Norepinephrine (Noradrenaline/NE).

- Effect: Generally inhibitory to GIT function.

- Origin: Originate from the spinal cord between segments T-5 and L-2.

- Path: Preganglionic fibers pass through the sympathetic chains to prevertebral ganglia (e.g., celiac ganglion, superior and inferior mesenteric ganglia). Postganglionic fibers then innervate essentially all of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Inhibitory Effects:

- Direct effect: To a slight extent, secreted Norepinephrine (NE) directly inhibits intestinal tract smooth muscle.

- Major effect: To a major extent, NE exerts an inhibitory effect on the neurons of the entire enteric nervous system, reducing its overall activity.

- Inhibit movements: Decrease motility.

- Decrease secretions: Reduce digestive gland activity.

- Cause constriction of sphincters: Helps in storing contents.

C. Afferent Sensory Nerve Fibers from the Gut

These vital fibers transmit sensory information from the GIT to various parts of the nervous system, initiating important reflexes.

- Transmission: Transmit sensory signals from the GIT into the brain (e.g., medulla), spinal cord, and prevertebral ganglia.

- Stimuli for Activation: Sensory nerves can be stimulated by:

- Irritation of the gut mucosa (e.g., presence of toxins, indicating potential harm or need for protective responses).

- Excessive distention of the gut (e.g., fullness, gas, signaling pressure).

- Presence of specific chemical substances in the gut (e.g., acid, nutrients, or toxins).

- Outcome: These signals can initiate vagal reflex signals that return to the GIT to control many of its functions.

II. Types of Movements in the GIT

GIT motility serves two primary functions: propelling food along the tract and mixing it with digestive juices.

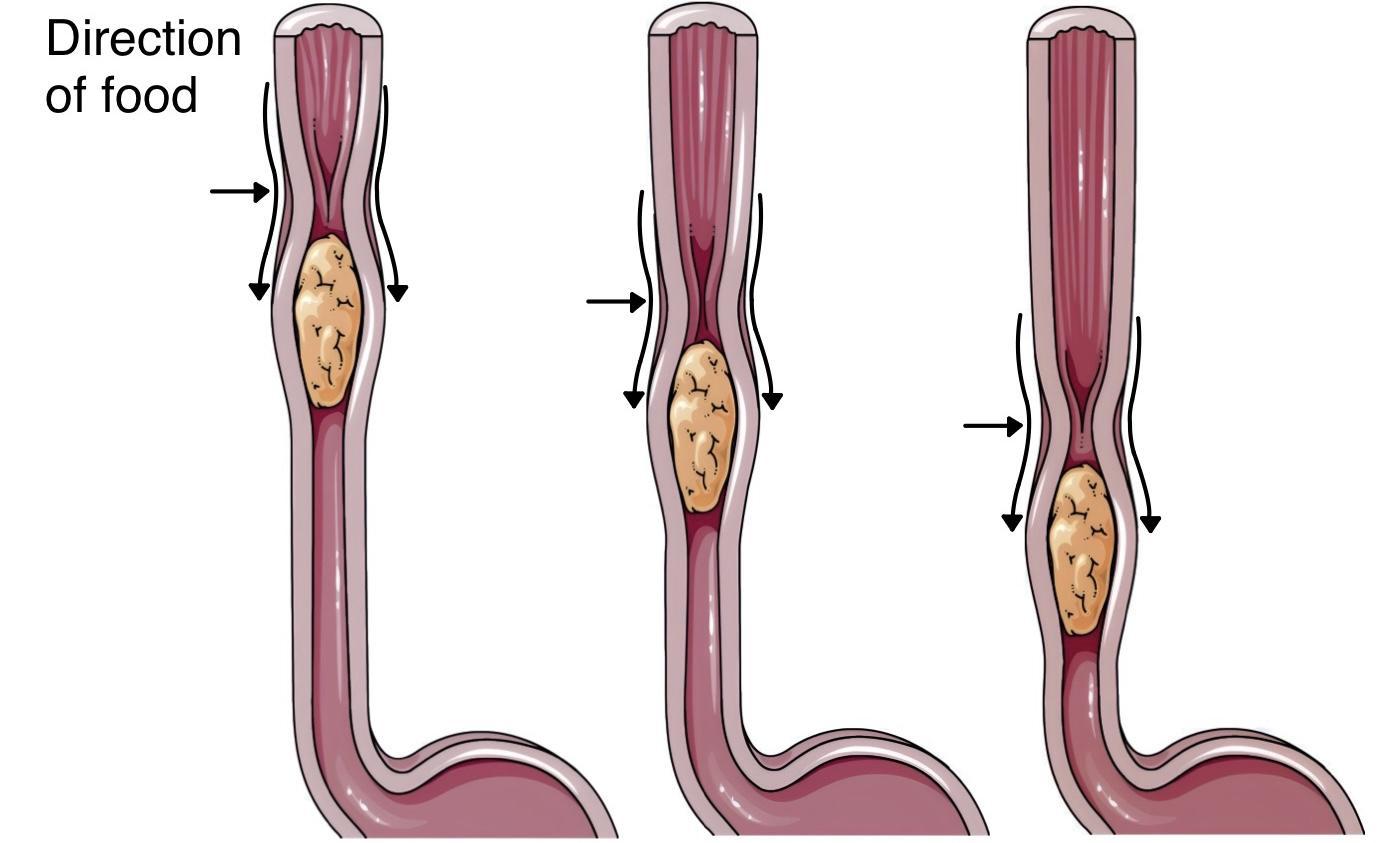

A. Propulsive Movements (Peristalsis):

- Purpose: To move food (chyme) forward along the tract at an appropriate rate for digestion and absorption.

- Basic Mechanism: Peristalsis is the fundamental propulsive movement.

- A contractile ring appears around the gut, and then moves forward.

- Material in front of the contractile ring is moved forward.

- Stimuli for Peristalsis:

- Distention of the gut: Stretching of the gut wall is a primary stimulus.

- Strong parasympathetic nervous signals: Enhance peristaltic activity.

- Neural Requirement: Effectual peristalsis requires an active myenteric plexus. Without it, peristalsis is weak or absent.

- Directionality: Although peristalsis can theoretically occur in either direction, it normally moves towards the anus. This is because the myenteric plexus is "polarized" in the anal direction.

- Law of the Gut: When a segment of the intestinal tract is excited by distention:

- A contractile ring forms on the oral (proximal) side of the distended segment and moves anally, pushing contents forward (typically 5-10 cm).

- Simultaneously, the gut downstream (anal side) of the distended segment undergoes "receptive relaxation," allowing easier propulsion of food. This complex pattern is entirely dependent on the myenteric plexus.

- Other Locations: Peristalsis is not exclusive to the GIT; it also occurs in bile ducts, glandular ducts, ureters, and other smooth muscle tubes.

B. Mixing Movements:

- Purpose: To thoroughly mix the intestinal contents with digestive juices and to facilitate contact with the absorptive surfaces of the mucosa.

- Mechanism: These vary in different parts of the alimentary tract. Often, they involve local, intermittent constrictive contractions (e.g., segmentation in the small intestine) that churn the contents without significant forward movement.

III. Regulation of Motility and Secretion

GIT function is regulated through neural reflexes and hormones.

A. Gastrointestinal Reflexes

The interplay between the intrinsic and extrinsic nervous systems gives rise to three basic types of reflexes that integrate and coordinate GIT function. These reflexes are categorized based on the extent of their neural circuits:

- Reflexes Entirely Within the Gut Wall (ENS):

- These are short reflexes that control local phenomena.

- Control: Regulating secretion, peristalsis, mixing movements, and local inhibitory effects in response to local stimuli (e.g., distention).

- Example: Peristaltic reflex in response to distention.

- Reflexes from the Gut to the Prevertebral Sympathetic Ganglia and Back to the GIT:

- These are long reflexes that travel outside the gut wall but do not involve the CNS directly.

- Gastrocolic reflex: Signals from the stomach (e.g., by distention from food intake) cause evacuation of the colon.

- Enterogastric reflexes: Signals from the colon and small intestine (e.g., due to excessive distention or irritation) inhibit stomach motility and stomach secretion, slowing gastric emptying.

- Colonoileal reflex: Signals from the colon inhibit emptying of ileal contents into the colon, preventing premature filling.

- Reflexes from the Gut to the Spinal Cord or Brain Stem and Then Back to the GIT:

- These are the longest and most complex reflexes, involving the CNS.

- Vagovagal reflexes: Reflexes from the stomach and duodenum to the brain stem and back to the stomach (via the vagus nerves) to control gastric motor and secretory activity.

- Pain reflexes: Strong pain signals from the gut (e.g., from severe injury or inflammation) can cause general inhibition of the entire GIT, shutting down activity.

- Defecation reflexes: Reflexes that travel from the colon and rectum to the spinal cord and back again to produce the powerful colonic, rectal, and abdominal contractions required for defecation.

B. Hormonal Control

Several hormones regulate various aspects of GIT function, often triggered by the presence of specific nutrients in the lumen.

Gastrin

Secreted by G cells in the stomach. Stimulates gastric acid secretion and mucosal growth.

Cholecystokinin (CCK)

Secreted by I cells in the duodenum and jejunum. Stimulates gallbladder contraction, pancreatic enzyme secretion, and inhibits gastric emptying.

Secretin

Secreted by S cells in the duodenum. Stimulates bicarbonate secretion from the pancreas and liver, and inhibits gastric acid secretion.

Gastroinhibitory Peptide (GIP)

Secreted by K cells in the duodenum and jejunum. Stimulates insulin secretion from the pancreas and inhibits gastric acid secretion.

Motilin

Secreted by M cells in the duodenum. Plays a role in initiating the migrating motor complex (MMC) during the interdigestive period.

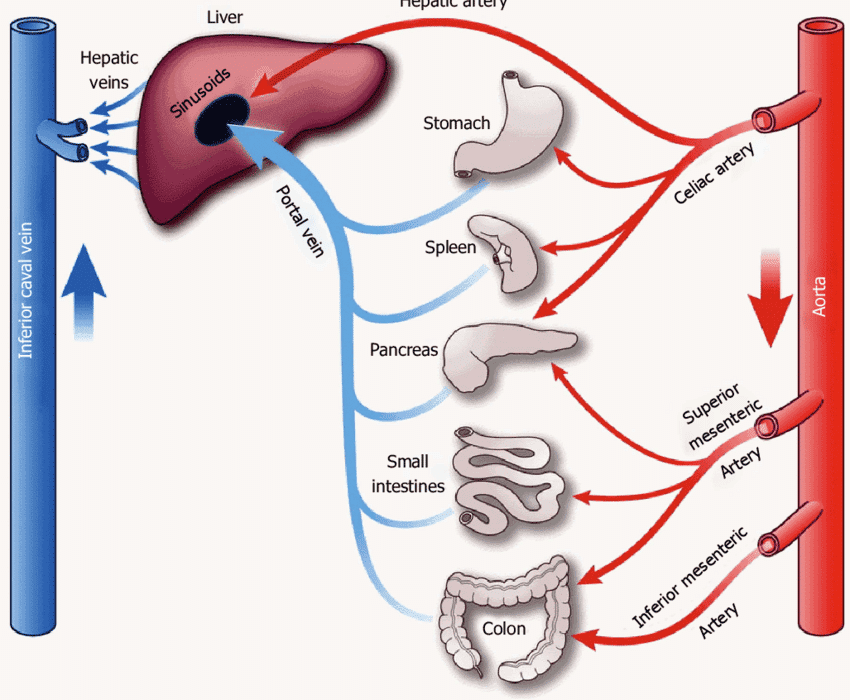

IV. Blood Flow to the GIT (Splanchnic Circulation)

The blood supply to the GIT is a vital component of the splanchnic circulation, which includes the vessels supplying the gut, spleen, pancreas, and liver.

A. Pathway of Splanchnic Blood Flow:

- All blood passing through the gut, spleen, and pancreas drains into the hepatic portal vein.

- This portal vein carries nutrient-rich, deoxygenated blood to the liver.

- In the liver, the blood passes through hepatic sinusoids, where nutrients are processed, and toxins are removed.

- Finally, blood leaves the liver via the hepatic veins and empties into the vena cava, returning to the systemic circulation.

B. Anatomy of GIT Blood Supply:

- The primary arterial supply comes from the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries.

- These arteries give rise to an arching arterial system, which then sends smaller arteries around the gut wall.

- Within the gut wall, these smaller arteries spread:

- Along the muscle bundles (for motility).

- Into the intestinal villi (for absorption).

- Into submucosal vessels beneath the epithelium (for secretion and absorption).

C. Effect of Gut Activity and Metabolic Factors on Blood Flow:

- Direct Relationship to Activity: Blood flow to the GIT is directly linked to its metabolic activity.

- During active nutrient absorption, blood flow in the villi and submucosa can increase up to 8-fold.

- Increased motor activity in the gut muscle layers also increases blood flow to those layers.

- Post-Meal Hyperemia: After a meal, motor, secretory, and absorptive activities all increase significantly, leading to a substantial increase in blood flow, which gradually returns to resting levels over 2-4 hours.

D. Possible Causes of Increased Blood Flow (Post-Meal):

While not fully understood, several factors contribute to the increased blood flow during digestion:

- Vasodilator Substances: Hormones released from the intestinal mucosa during digestion act as vasodilators (e.g., CCK, VIP, gastrin, secretin).

- Kinins: GIT glands release kinins like kallidin and bradykinin, which are potent vasodilators and are secreted along with other glandular secretions.

- Decreased Oxygen Concentration: Increased metabolic activity and nutrient absorption lead to reduced oxygen concentration in the gut wall, which directly causes vasodilation (via substances like adenosine) to increase blood flow by 50-100%.

E. Importance of Sympathetic Vasoconstriction in the GIT:

- Redistribution of Blood: The sympathetic nervous system can cause strong vasoconstriction in the splanchnic circulation. This is crucial for:

- Exercise: Shutting off gut blood flow allows more blood to be diverted to active skeletal muscles and the heart during heavy exercise.

- Circulatory Shock: In conditions like hemorrhagic shock or other states of low blood volume, sympathetic stimulation can severely decrease splanchnic blood flow for many hours. This protects vital organs like the brain and heart by diverting blood to them.

- Blood Volume Regulation: Sympathetic stimulation also causes strong vasoconstriction of the large-volume intestinal and mesenteric veins. This significantly decreases the volume of these veins, displacing a large amount of blood (200-400 ml) into the central circulation, thereby helping to sustain general circulation in emergencies.

GIT Motility: Ingestion of Food and Stomach Functions

The journey of food through the digestive system begins with ingestion, a process driven by both physiological and psychological factors, and followed by mechanical and chemical processing in the stomach.

I. Ingestion of Food

Ingestion is influenced by internal drives and preferences, and involves the mechanical processes of chewing and swallowing.

- Hunger: An intrinsic desire for food. Primarily determines the amount of food ingested.

- Appetite: Determines the type of food a person preferentially seeks. More psychological, influenced by learned preferences, culture, and sensory experiences.

A. Chewing (Mastication):

- Purpose: Essential for proper digestion, as digestive enzymes can only act on the surfaces of food particles. It also prevents excoriation of the GIT and aids in smooth emptying from the stomach.

- Teeth Adaptation:

- Incisors: Designed for a strong cutting action.

- Molars: Designed for a grinding action.

- Force: Jaw muscles can exert significant force (up to 55 pounds on incisors, 200 pounds on molars).

- Muscles: Innervated by the motor branch of the 5th cranial nerve (trigeminal nerve).

- Control: The chewing process is largely controlled by nuclei in the brain stem and primarily results from the chewing reflex.

- Chewing Reflex Mechanism:

- Presence of food (bolus) in the mouth initiates reflex inhibition of mastication muscles.

- This allows the lower jaw to drop.

- The drop initiates a stretch reflex in the jaw muscles, leading to rebound contraction.

- This raises the jaw, causing teeth closure and compressing the bolus against the mouth linings.

- This compression again inhibits the jaw muscles, allowing the jaw to drop and rebound, repeating the cycle automatically.

B. Swallowing (Deglutition):

Nature: A complicated mechanism due to the dual function of the pharynx (respiration and digestion). It is a rapid process to prevent interruption of respiration.

Stages of Swallowing:

- Voluntary Stage (Oral Stage): Initiates the swallowing process. Food (bolus) is voluntarily squeezed or rolled posteriorly into the pharynx by the tongue.

- Pharyngeal Stage (Involuntary): Food passes through the pharynx into the esophagus. Triggered by stimulation of epithelial swallowing receptor areas (e.g., tonsillar pillars). A complex series of involuntary actions occurs rapidly:

- Soft palate pulled upward to close off the nasopharynx.

- Palatopharyngeal folds move medially to form a sagittal slit, allowing only properly chewed food to pass.

- Vocal cords approximate, and the larynx moves upward and forward.

- Epiglottis swings backward over the glottis (opening to trachea), preventing food entry into the trachea.

- The upper esophageal sphincter relaxes, allowing food to enter the esophagus.

- A rapid peristaltic wave begins in the pharynx, forcing food into the esophagus.

- Esophageal Stage (Involuntary): Food moves from the pharynx through the esophagus into the stomach. Primarily accomplished by peristalsis:

- Primary peristalsis: A continuation of the pharyngeal peristaltic wave, traveling the entire length of the esophagus in about 8-10 seconds.

- Secondary peristalsis: If the primary wave fails to move all the food, distention of the esophagus by residual food triggers new waves of secondary peristalsis. These waves continue until the esophagus is cleared.

- The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxes ahead of the peristaltic wave, allowing food to pass into the stomach.

- Dysphagia (Difficulty in Swallowing):

- Causes: Mechanical obstruction (e.g., tumors, strictures), Decreased esophageal movement due to neurological disorders (Parkinsonism, stroke), Muscular disorders.

- Esophageal Achalasia: A neuromuscular disease characterized by impaired relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter and absence of peristalsis in the lower esophagus. Leads to accumulation of food in the esophagus.

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): Regurgitation of acidic gastric content through the esophagus. Results from incompetence of the lower esophageal sphincter, causing heartburn and potential damage.

II. Motor Functions of the Stomach

The stomach plays crucial roles in the initial processing of food, acting as a storage organ, a mixing chamber, and a regulator of chyme delivery to the small intestine.

Three Main Functions:

- Storage: Stores large quantities of food until it can be processed.

- Mixing: Mixes food with gastric secretions to form a semi-fluid mixture called chyme.

- Slow Emptying: Slowly empties chyme from the stomach into the small intestine at a rate suitable for proper digestion and absorption.

A. Physiologic Anatomy of the Stomach:

- Anatomically: Divided into the fundus, body, and antrum.

- Physiologically: Divided into two main functional areas:

- "Orad" Portion: Comprises about the first two-thirds of the body and the fundus. Primarily functions as a storage area.

- "Caudad" Portion: Comprises the remainder of the body plus the antrum. Primarily functions as the mixing and propulsion area.

B. Stomach Motility:

- Receptive Relaxation (Storage Function):

- When food distends the stomach, it initiates a vagovagal reflex.

- This reflex causes the orad region to relax, accommodating the ingested meal.

- Cholecystokinin (CCK) increases the distensibility of the orad stomach.

- Pressure within the stomach remains low until its capacity (about 0.8 to 1.5 liters) is approached.

- Mixing and Propulsion (Processing Function):

- The caudad region contracts vigorously to mix food with gastric secretions.

- Constrictor waves (mixing waves): These begin from the mid-upper portion of the stomach wall and move towards the antrum, occurring every 15-20 seconds.

- Basic Electrical Rhythm (BER): These constrictor waves are initiated by the stomach's intrinsic electrical activity (slow waves).

- As constrictor waves progress towards the antrum, they become more intense, providing a powerful peristaltic action.

- Retropulsion (Mixing Mechanism): The pyloric muscle contracts, impeding emptying and squeezing the antral contents upstream, back towards the stomach body. This combination of moving constrictor rings and the upstream squeezing action is highly effective for mixing, resulting in the formation of chyme.

- Hunger Contractions:

- Occur when the stomach has been empty for several hours.

- Rhythmical peristaltic contractions in the body of the stomach.

- Extremely strong contractions can fuse to form a continuous tetanic contraction lasting 2-3 minutes.

- Greatly increased in individuals with lower than normal blood sugar levels.

- Can be associated with mild pain sensation (hunger pangs).

C. Stomach Emptying (Regulation of Chyme Delivery):

- Mechanism: Intense peristaltic contractions in the stomach antrum generate significant pressure (up to 50-70 cm H2O), acting as a "pyloric pump" to promote emptying.

- Pyloric Sphincter: The pylorus is tonically contracted, providing resistance to emptying.

- Regulation of Emptying Rate:

- Isotonicity: The rate is fastest when the stomach contents are isotonic.

- Duodenal Chyme Volume: Too much chyme in the small intestine inhibits gastric emptying.

- Fat Content: Fat is a potent inhibitor of gastric emptying. It stimulates the release of CCK, which reduces gastric motility.

- Acidity (H+ in Duodenum): The presence of H+ (acidity) in the duodenum strongly inhibits gastric emptying via direct neural reflexes.

GIT Motility: Small Intestine, Colon, and Defecation

I. Small Intestine Movements

The small intestine is primarily responsible for the digestion and absorption of nutrients. Its motility patterns are crucial for mixing chyme with digestive juices and slowly propelling it forward.

1. Mixing Movements (Segmentation Contractions)

- Trigger: Distention of the small intestine by chyme.

- Mechanism: Localized contractions of circular muscles that divide the intestine into segments. These contractions churn the chyme, mixing it thoroughly with digestive enzymes and bringing it into contact with the absorptive mucosa.

- Frequency: Depends on the electrical activity of slow waves (BER). Maximum freq: ~12/min. Normal range: 8-9/min (decreases along the length, creating a pressure gradient).

2. Propulsive Movements (Peristaltic Waves)

- Function: To propel chyme through the small intestine.

- Velocity: Relatively slow (0.5 to 2.0 cm/second).

- Characteristics: Peristaltic waves are normally very weak and usually die out after traveling 3-5 cm.

- Time for Transit: 3 to 5 hours from pylorus to ileocecal valve.

- Gastroileal Reflex: Immediately after a new meal, this reflex enhances ileal peristalsis and causes relaxation of the ileocecal sphincter.

- Peristaltic Rush: Severe irritation (e.g., infectious agents) leads to powerful and rapid peristaltic contractions sweeping the entire length, often resulting in diarrhea.

II. Movements of the Colon (Large Intestine)

The colon has two primary functions: Absorption of water/electrolytes (proximal half) and Storage of fecal matter (distal half). Movements are generally very sluggish.

1. Mixing Movements (Haustrations)

- Mechanism: Large circular constrictions involving simultaneous contraction of circular and longitudinal muscles.

- Appearance: Unstimulated portions bulge outward, forming bag-like sacs called haustrations.

- Dynamics: Peak contraction in 30 seconds, disappears over next 60 seconds.

- Effect: Slow, churning action that "digs into" and "rolls over" fecal material, facilitating absorption.

2. Propulsive Movements (Mass Movements)

- Nature: Strong, rapid, infrequent propulsive movements unique to the colon.

- Triggers: Often initiated by gastrocolic and duodenocolic reflexes (after a meal).

- Transit Time: 8 to 15 hours to move chyme from ileocecal valve through the colon.

- Sequence: A constrictive ring forms -> rapid unified contraction of a segment (20cm) distal to the ring -> propels fecal material down -> contraction lasts ~30 secs, relaxation 2-3 mins. Occurs 1-3 times a day.

III. Defecation

Defecation is the final act of gastrointestinal motility, involving the expulsion of feces from the body.

- Rectal Status: The rectum is usually empty of feces.

- Urge to Defecate: When a mass movement forces feces into the rectum, the distention of the rectal wall immediately creates the desire for defecation.

- Prevention of Incontinence:

- Internal Anal Sphincter: Smooth muscle, tonic constriction, involuntary control.

- External Anal Sphincter: Striated (skeletal) muscle, tonic constriction, voluntary control.

IV. Defecation Reflexes

These reflexes initiate and facilitate the act of defecation.

- Intrinsic Defecation Reflex:

- Mediated by: The local Enteric Nervous System (ENS) within the rectal wall.

- Mechanism: Rectal distention stimulates stretch receptors -> signals via myenteric plexus -> peristaltic waves in descending/sigmoid colon and rectum -> inhibition of internal anal sphincter. (Relatively weak on its own).

- Parasympathetic Defecation Reflex:

- Involves: The sacral segments of the spinal cord (spinal cord reflex).

- Mechanism: Rectal distention signals to spinal cord -> efferent parasympathetic signals via pelvic nerves -> intensify peristaltic waves and further relax internal anal sphincter.

- Voluntary Control: The external anal sphincter allows an individual to either permit defecation or consciously constrict the sphincter to inhibit it.

V. Other Autonomic Reflexes Affecting Bowel Activity

Peritoneointestinal Reflex

Trigger: Irritation of the peritoneum (e.g., peritonitis).

Effect: Strongly inhibits excitatory enteric nerves, leading to intestinal paralysis (ileus).

Renointestinal and Vesicointestinal Reflexes

Trigger: Irritation of the kidneys or bladder.

Effect: Inhibits intestinal activity.

Digestive System, GIT Neuro & Motility Quiz

Systems Physiology

Enter your details to begin the examination.

🛡️ Privacy Note: Results are for tracking and certification purposes only.

Digestive System, GIT Neuro & Motility Quiz

Systems Physiology

Preparing questions...

Exam Completed!

See your performance breakdown below.