Germ Disc, Gastrulation & Neurulation: Fortion of Organs

Brief Recap

We concluded our last discussion with the blastocyst successfully implanted (around Day 12 post-fertilization) into the uterine endometrium. At this point:

- The blastocyst is fully embedded in the decidua (the transformed endometrial tissue).

- The trophoblast has differentiated into:

- Cytotrophoblast (inner layer, cellular).

- Syncytiotrophoblast (outer layer, invasive, multinucleated, producing hCG).

- The inner cell mass (embryoblast) is now clearly visible and undergoing significant changes, leading to the formation of the embryonic disc and associated cavities.

Formation of the Bilaminar Embryonic/Germ Disc and Associated Cavities (Week 2 Development)

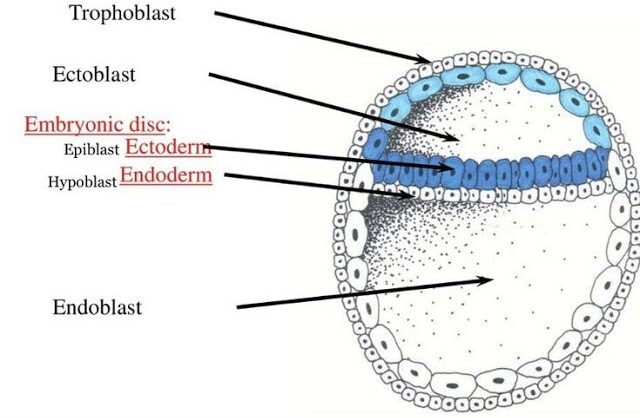

This period, roughly from Day 8 to Day 14 post-fertilization, is often referred to as "the week of twos" because several structures differentiate into two layers or cavities. It's a phase of rapid differentiation of the inner cell mass.

After fertilization and cleavage, the embryo, now a blastocyst, undergoes profound organizational changes. It remodels itself from a sphere into a flattened, two-layered structure known as the Bilaminar Germ Disc. This process is crucial as it sets the stage for gastrulation, where the three primary germ layers will form.

1. From Blastocyst to Bilaminar Germ Disc

This transformation begins around Day 8 post-fertilization, as the Inner Cell Mass (ICM) differentiates.

A. Differentiation of the Inner Cell Mass:

The inner cell mass (embryoblast) differentiates into two distinct layers that collectively form a flat, circular structure called the bilaminar embryonic disc:

Epiblast (Dorsal/Upper Layer)

A layer of columnar cells facing the developing amniotic cavity. Crucially, all three primary germ layers of the embryo will eventually originate from the epiblast.

- Location: The dorsal (upper) layer of the disc.

- Cell Type: Consists of tall, columnar cells.

- Relation to Cavity: It is directly adjacent to what will become the amniotic cavity.

- Significance: The epiblast is the source of all three primary germ layers during gastrulation. It is essentially the "true" embryonic component at this stage.

Hypoblast (Ventral/Lower Layer)

A layer of cuboidal cells facing the blastocoel. It primarily contributes to extraembryonic membranes, particularly the yolk sac.

- Location: The ventral (lower) layer of the disc, beneath the epiblast.

- Cell Type: Consists of small, cuboidal cells.

- Relation to Cavity: It is directly adjacent to what will become the primary yolk sac.

- Significance: While the hypoblast does not contribute directly to the embryo proper's germ layers, it plays crucial roles in signaling, guiding epiblast cell movements, and forming the extraembryonic endoderm lining of the yolk sac.

B. Formation of Associated Cavities:

As the epiblast and hypoblast differentiate, two fluid-filled cavities form in close association with them:

Amniotic Cavity

- Formation: A small cavity appears within the epiblast and expands.

- Lining: The roof of this cavity is formed by amnioblasts (cells that differentiate from the epiblast and line the amniotic cavity). The floor is the epiblast itself.

- Contents: It will eventually be filled with amniotic fluid, which protects the developing embryo/fetus.

Primary Yolk Sac (Exocoelomic Cavity)

- Formation: Cells from the hypoblast migrate and spread along the inner surface of the cytotrophoblast, forming a thin membrane called the exocoelomic membrane (Heuser's membrane). This membrane, together with the hypoblast, encloses a new cavity, the primary yolk sac.

- Contents: Contains fluid and plays a role in early nutrient transfer and blood cell formation.

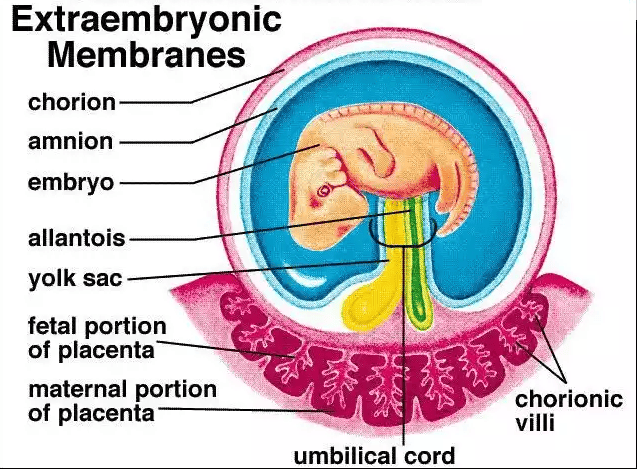

C. Development of Extraembryonic Structures:

During this same period (Week 2), other crucial extraembryonic structures are forming:

Origin: A loose connective tissue layer that develops between the cytotrophoblast and the exocoelomic membrane/amnion.

Cavitation: This mesoderm soon develops large cavities, forming the extraembryonic coelom (chorionic cavity). This cavity completely surrounds the amnion and the primary yolk sac, except where the embryonic disc is connected to the trophoblast by the connecting stalk (which will become the umbilical cord).

Amniotic Cavity

A new fluid-filled space that appears within the epiblast, enclosed by a thin membrane called the amnion. It will eventually surround the entire embryo.

As the extraembryonic coelom forms, the primary yolk sac shrinks, and a new, smaller secondary yolk sac forms from a second wave of hypoblast cells. This is the definitive yolk sac of the embryo.

Primary Umbilical Vesicle (Yolk Sac)

Forms when hypoblast cells line the blastocoel. In humans, it plays roles in early blood cell formation and nutrient transfer.

The extraembryonic mesoderm, together with the two layers of the trophoblast (cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblast), forms the chorion.

The chorion is the outermost fetal membrane and will eventually contribute to the fetal part of the placenta. The chorionic cavity is the space within the chorion.

Extraembryonic Mesoderm & Coelom

A new layer of mesoderm forms between the yolk sac/amnion and the trophoblast. A large cavity, the chorionic cavity (or coelom), then forms within this mesoderm, suspending the embryo by a connecting stalk.

D. Establishment of Body Axes (Preliminary):

By the end of Week 2, some crucial axes begin to be established, even before gastrulation formally begins:

- Dorsoventral Axis: Already defined by the epiblast (dorsal) and hypoblast (ventral).

- Cranial-Caudal Axis: The future head end (cranial) is distinguished from the future tail end (caudal) by the appearance of a localized thickening of the hypoblast, the prechordal plate, at the future cranial region. This is an important signaling center.

- Left-Right Asymmetry: While not yet morphologically apparent, molecular signals are starting to be laid down that will determine left-right patterning.

Summary of Bilaminar Disc Development (Week 2):

- Inner cell mass differentiates into Epiblast and Hypoblast.

- These form the Bilaminar Embryonic Disc.

- Amniotic Cavity forms above the epiblast.

- Primary Yolk Sac forms below the hypoblast, later replaced by the Secondary Yolk Sac.

- Extraembryonic Mesoderm and Extraembryonic Coelom develop, surrounding the amnion and yolk sac.

- The Chorion (trophoblast + extraembryonic mesoderm) encases everything.

- A Connecting Stalk links the embryonic disc to the trophoblast.

Clinical Significance

This highly sensitive period is critical for assessing early embryonic viability. Disruptions during germ disc formation can lead to severe birth defects, and this is when issues like ectopic pregnancies become apparent.

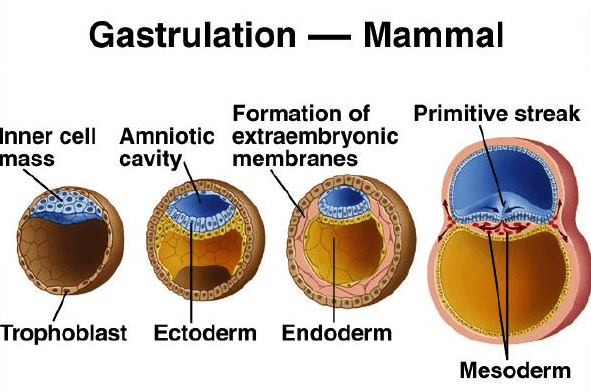

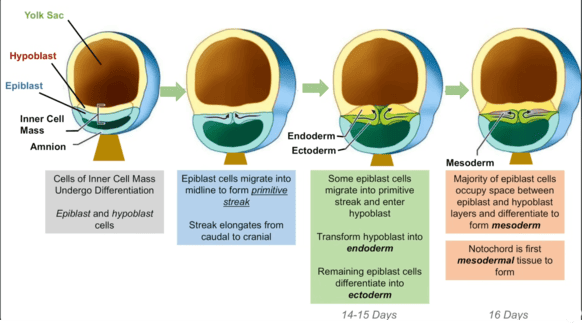

4. Transition to Gastrulation

The formation of the bilaminar germ disc is the final preparatory step before gastrulation begins in week 3. During gastrulation, cells from the epiblast will migrate inward through the primitive streak to form the three definitive germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) that will give rise to the entire body.

Gastrulation: Formation of Germ Layers and Body Axis

Gastrulation is a highly complex and critical developmental process that involves the dramatic reorganization and movement of embryonic cells. This process transforms the simple, two-layered bilaminar disc into a three-layered structure.

These three layers, known as the primary germ layers, are the foundational tissues from which all organs and tissues of the body will ultimately develop. In humans, gastrulation occurs around week 3 of embryonic development, after the blastocyst has successfully implanted.

Key Events of Gastrulation

Gastrulation is initiated by two fundamental events that establish the blueprint for the developing embryo.

1. Formation of the Primitive Streak

A thickened line of cells forms on the dorsal surface of the epiblast. The primitive streak is profoundly important as it establishes all major body axes: anterior-posterior (head-tail), dorsal-ventral (back-belly), and medial-lateral.

2. Cell Migration & Invagination

Epiblast cells migrate towards the primitive streak and then "dive" inward in a process called invagination. It is this inward migration and subsequent differentiation that forms the new germ layers.

Formation of the Primitive Streak

Gastrulation begins with the formation of a distinct linear structure on the surface of the epiblast, known as the primitive streak. This is the first morphological sign that the embryo is transitioning from a simple disc to a more complex, three-dimensional structure with defined axes.

A. Timing and Location:

- Timing: The primitive streak appears around Day 15-16 post-fertilization.

- Location: It forms on the dorsal surface of the epiblast, specifically at the caudal end of the embryonic disc.

- Elongation: Once formed, it rapidly elongates in a cranial (headward) direction, reaching about half the length of the embryonic disc by Day 17-18.

B. Structure of the Primitive Streak:

As the primitive streak elongates, it develops specific anatomical features:

1. Primitive Groove

Description: A narrow, shallow depression that runs along the midline of the primitive streak.

Function: This groove is the actual passageway or "mouth" through which epiblast cells will migrate inwards, a process called ingression (or sometimes referred to as invagination, though ingression is more precise for individual cell migration).

2. Primitive Node (Hensen's Node)

Description: A distinct, slightly elevated, knob-like or pit-like structure located at the most cranial (anterior) end of the primitive streak.

Function: The primitive node is a crucial organizing center for gastrulation and subsequent development. Cells passing through the primitive node have a distinct fate, forming the notochord and prechordal plate. It's also involved in establishing left-right asymmetry.

3. Primitive Pit

Description: A small depression or pit located in the center of the primitive node. It is essentially the cranial-most opening of the primitive groove.

Function: This is the entry point for cells destined to form the notochord.

C. Significance of the Primitive Streak:

The primitive streak is far more than just a visible landmark; it is the central organizing structure of gastrulation and critical for establishing the fundamental body plan:

- Defines Embryonic Axes:

- Cranial-Caudal Axis: Its appearance defines the cranial (head) and caudal (tail) ends of the embryo. The primitive streak itself forms at the caudal end and extends cranially.

- Medial-Lateral Axis: The streak runs along the midline, establishing the embryo's central axis.

- Dorso-Ventral Axis: Already established by the epiblast/hypoblast arrangement.

- Left-Right Axis: While not morphologically obvious at this stage, molecular signals originating around the primitive node begin to establish this crucial asymmetry.

- Gateway for Cell Migration: It is the exclusive site for epiblast cells to ingress into the interior of the embryo to form the new germ layers. Without the primitive streak, gastrulation cannot occur.

- Source of Inductive Signals: The primitive node, in particular, acts as a signaling center, producing factors that influence the differentiation of surrounding cells and contribute to processes like neural induction (later).

D. Molecular Regulation of Primitive Streak Formation:

The precise formation and maintenance of the primitive streak are orchestrated by a complex interplay of signaling molecules:

Nodal plays a central role in initiating and maintaining the primitive streak, promoting cell ingression, and influencing cell fate. It's often found in a gradient, with higher concentrations at the caudal end.

Produced throughout the epiblast and primitive streak. High levels generally promote ventral mesoderm fates (e.g., blood and kidney precursors), while antagonists of BMP (like Chordin and Noggin, produced by the primitive node) allow for neural development.

Secreted by primitive streak cells, FGF8 is crucial for controlling cell migration through the streak and maintaining its integrity. It also works with Nodal to specify mesodermal lineages.

Involved in establishing and maintaining the posterior (caudal) identity of the primitive streak.

A transcription factor expressed in the primitive streak and notochord. It is essential for mesoderm formation and differentiation, and for the elongation of the primitive streak and notochord.

So, we now have our active, elongating primitive streak, complete with its groove, node, and pit. This structure is precisely positioned and signaling actively, preparing for the most dramatic cellular rearrangement: the actual movement of epiblast cells to form the three germ layers.

The Three Primary Germ Layers

As cells invaginate and migrate, they arrange themselves into three distinct layers, each with a specific developmental fate.

Cell Migration and Ingression: The Formation of the Three Primary Germ Layers

This is the heart of gastrulation. It involves the dynamic movement and differentiation of epiblast cells as they pass through the primitive streak.

A. The Process of Ingression:

Key Mechanisms

- Epiblast as the Source: All three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) originate exclusively from the epiblast. The hypoblast is displaced and does not contribute to the embryo proper.

- Convergent Extension: Epiblast cells around the primitive streak undergo active changes. They begin to proliferate, lose their epithelial characteristics (cell-to-cell junctions), become bottle-shaped, and detach from the epiblast layer.

- Movement into the Groove: These cells then migrate towards and move into the primitive groove.

- Ingression vs. Invagination: This process of individual epiblast cells detaching from the surface layer and moving into the space between the epiblast and hypoblast is called ingression. It is distinct from invagination, where an entire sheet of cells folds inwards.

- Cellular Transformation (EMT): As they ingress, these cells undergo an Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT). They lose their apical-basal polarity, shed adhesion molecules, and gain migratory properties, becoming mesenchymal cells.

B. Formation of the Definitive Endoderm:

The first wave of epiblast cells to ingress through the primitive groove has a very specific destination and function:

- Ingression: These pioneering cells migrate through the primitive groove and move ventrally (downwards).

- Displacement of Hypoblast: They position themselves beneath the epiblast and effectively displace the existing hypoblast cells. The hypoblast cells are pushed out towards the periphery, where they contribute to the extraembryonic membranes of the yolk sac.

- Formation of Definitive Endoderm: The newly migrated epiblast cells replace the hypoblast to form the definitive endoderm. This layer will ultimately form the lining of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts, and associated glands (e.g., liver, pancreas).

C. Formation of the Intraembryonic Mesoderm:

Once the definitive endoderm is established, subsequent waves of epiblast cells ingress through the primitive groove, forming the middle germ layer:

- Continued Ingression: More epiblast cells migrate through the primitive groove.

- Formation of Mesenchymal Layer: Instead of displacing cells, these new cells move into the space between the newly formed definitive endoderm and the remaining epiblast. They spread out laterally and cranially.

- Formation of Intraembryonic Mesoderm: This intervening layer of loosely organized mesenchymal cells constitutes the intraembryonic mesoderm. This mesoderm will give rise to a vast array of tissues and organs, including muscle, bone, connective tissue, circulatory system, and urogenital system.

D. Formation of the Definitive Ectoderm:

After the endoderm and mesoderm have been formed by ingressing cells, the remaining epiblast cells that did not ingress through the primitive streak undergo a fate change:

- Remaining Epiblast: The cells that stay on the dorsal surface of the embryonic disc, remaining in the epiblast layer, are now designated as the definitive ectoderm.

- Future Development: This ectoderm will give rise to the epidermis (skin and its appendages), the nervous system (brain and spinal cord), and sensory organs.

Summary of Germ Layer Formation through Ingression

- Epiblast Cells (the original upper layer of the bilaminar disc) are the sole source.

- First Wave (through primitive groove) → displaces Hypoblast → forms Definitive Endoderm.

- Second Wave (through primitive groove) → occupies space between Epiblast & Endoderm → forms Intraembryonic Mesoderm.

- Remaining Epiblast → forms Definitive Ectoderm.

E. Special Mesodermal Derivatives from the Primitive Node

While the bulk of the mesoderm forms through the primitive groove, cells ingressing specifically through the primitive node and primitive pit have special fates:

The Notochord

Origin: Cells ingressing through the primitive pit (at the very cranial end of the primitive node) migrate cranially along the midline.

Formation: They form a rod-like structure called the notochordal process. This process then elongates and hollows, forming the notochordal canal, before fusing with the endoderm and eventually detaching to form the solid notochord.

- Defines the primitive axis of the embryo.

- Provides some rigidity.

- Serves as the basis for the axial skeleton (vertebral column will form around it).

- Is crucial for neural induction: it induces the overlying ectoderm to form the neural plate (the precursor to the brain and spinal cord).

- Plays a role in determining the dorsal-ventral axis of the neural tube and somites.

Fate: In adults, the notochord remnants persist as the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral discs.

Prechordal Plate

Origin: Some cells that ingress through the primitive node and migrate cranially, but do not become part of the notochord.

Location: They form a small, localized region of mesoderm just cranial (anterior) to the notochord.

Significance: The prechordal plate is an important signaling center for the development of the forebrain and cranial structures. It also contributes to the cranial mesoderm.

At this point, the embryo has been transformed into a trilaminar embryonic disc, with distinct ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm layers. The notochord is forming, defining the central axis and setting the stage for nervous system development.

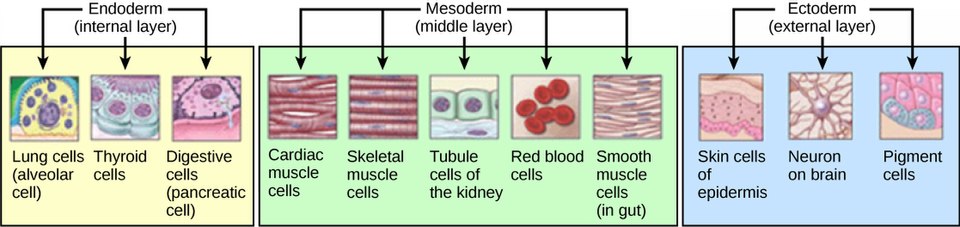

Derivatives of the Three Primary Germ Layers (An Overview)

It is crucial to understand that each of these newly formed germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) is programmed to give rise to specific tissues, organs, and systems in the developing embryo. This is a high-level overview; we will delve deeper into organogenesis later.

A. Ectoderm (The "Outer" Layer)

The ectoderm differentiates into two main components: surface ectoderm and neuroectoderm.

1. Surface Ectoderm

- Epidermis: The outer layer of skin, including hair, nails, and sebaceous glands.

- Cutaneous Glands: Sweat glands, mammary glands.

- Oral Epithelium: Lining of the mouth, enamel of teeth.

- Sensory Epithelium of Sense Organs: Lens of the eye, inner ear, olfactory (smell) epithelium.

- Anterior Pituitary Gland: (Rathke's pouch derivation).

- Adrenal Medulla: (Modified post-ganglionic sympathetic neurons).

- Pineal Gland.

2. Neuroectoderm

- Neural Plate/Tube: Brain (forebrain, midbrain, hindbrain), spinal cord.

- Peripheral Nervous System: All neurons and glial cells outside the brain and spinal cord, including cranial nerves, spinal nerves, and autonomic ganglia.

- Retina of the Eye: And optic nerve.

- Posterior Pituitary Gland: (Neurohypophysis).

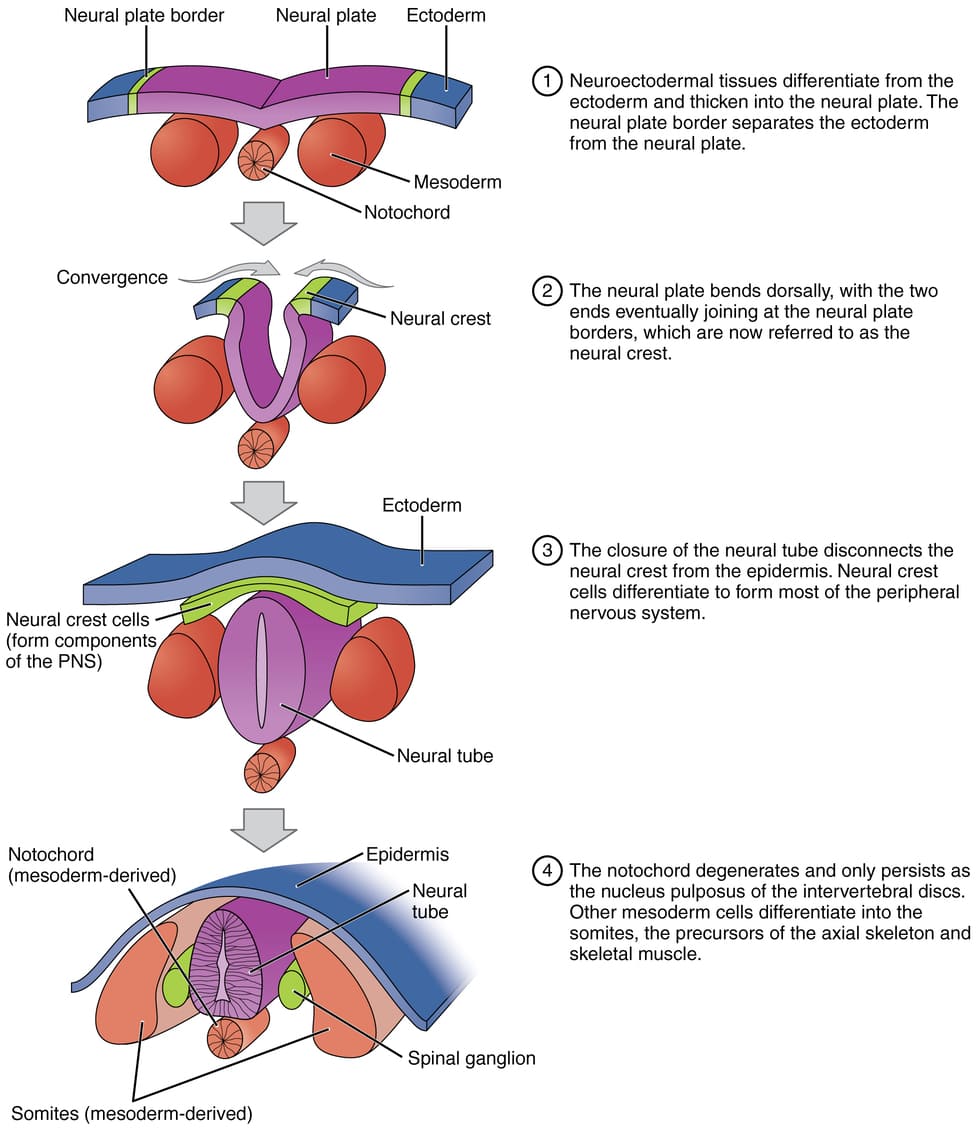

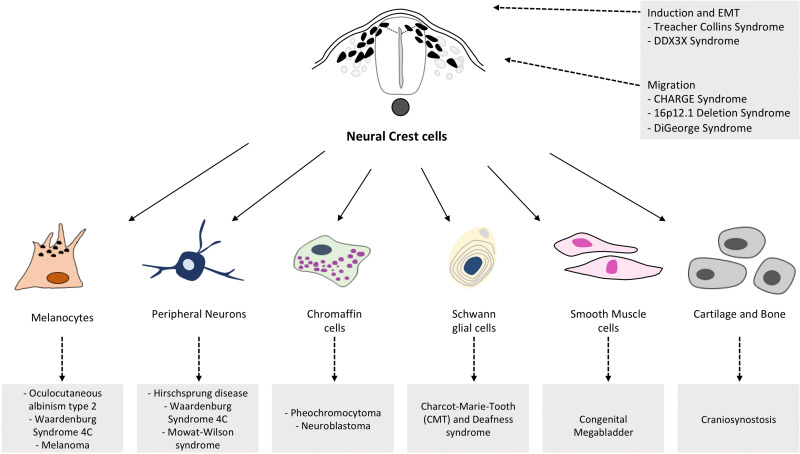

3. Neural Crest Cells

A special population of cells that delaminate from the edges of the neural plate/tube. They are often considered the "fourth germ layer" due to their widespread migratory capabilities and diverse derivatives:

- Craniofacial Structures: Bones, cartilage, connective tissue of the face and skull.

- PNS Components: Sensory neurons, autonomic ganglia, Schwann cells.

- Endocrine Glands: Adrenal medulla, C-cells of the thyroid.

- Pigment Cells: Melanocytes (skin pigmentation).

- Cardiac Development: Septa of the outflow tract of the heart.

B. Mesoderm (The "Middle" Layer)

The mesoderm is arguably the most diverse germ layer, giving rise to connective tissues, muscles, and circulatory system components. It differentiates into distinct regions:

Forms somites (blocks of tissue that appear sequentially along the neural tube).

- Sclerotome: Vertebrae and ribs.

- Myotome: Skeletal muscle of the trunk and limbs.

- Dermatome: Dermis of the skin (connective tissue under epidermis).

- Urinary System: Kidneys, ureters, bladder.

- Gonads: Ovaries and testes.

- Reproductive Ducts: Portions of the male and female reproductive tracts.

Divides into two layers separated by the intraembryonic coelom (future body cavities).

Forms the parietal layer of serous membranes (lining body walls), connective tissue of limbs, and parts of the sternum.

Forms the visceral layer of serous membranes (covering organs), smooth muscle and connective tissue of internal organs (e.g., gut wall, respiratory tract), and heart and circulatory system (blood vessels, blood cells, lymphatic vessels).

Undifferentiated mesoderm in the cranial region, contributes to connective tissues and muscles of the head.

C. Endoderm (The "Inner" Layer)

The endoderm primarily forms the epithelial lining of internal organs and associated glands.

- Gastrointestinal Tract: Epithelial lining from the pharynx to the rectum (excluding portions of the oral cavity and anal canal, which are ectodermal).

- Respiratory Tract: Epithelial lining of the larynx, trachea, bronchi, and alveoli of the lungs.

- Accessory Digestive Glands: Liver, pancreas, gallbladder (their epithelial components).

- Thyroid Gland, Parathyroid Glands, Thymus: (Epithelial components).

- Epithelial Lining of Urinary Bladder: And most of the urethra.

- Epithelial Lining of Auditory Tube and Tympanic Cavity.

To Summarize;

Ectoderm (Outer Layer)

Formed from the remaining cells of the epiblast that do not invaginate.

Future Structures:

- Nervous System (brain, spinal cord, nerves)

- Epidermis of Skin (including hair and nails)

- Sensory Organs (eyes, ears)

Mesoderm (Middle Layer)

Formed from the cells that invaginate and migrate to lie between the epiblast and the newly formed endoderm.

Future Structures:

- Muscles, Bones, and Cartilage

- Circulatory System (heart, blood, vessels)

- Kidneys and Reproductive Organs

Endoderm (Inner Layer)

Formed from the first cells that invaginate and displace the original hypoblast layer.

Future Structures:

- Lining of the Digestive Tract (and associated glands like the liver and pancreas)

- Lining of the Respiratory System (lungs)

- Lining of the Bladder

6. Other Key Structures Formed or Established During Gastrulation

Beyond the germ layers, gastrulation is crucial for defining several other foundational structures:

A. Notochord

Recap: Forms from cells ingressing through the primitive node, migrating cranially, forming the notochordal process, and eventually solidifying into the definitive notochord.

Critical Role: The notochord defines the embryonic midline, acts as a primary inducer for the overlying ectoderm to form the neural plate (the first step in central nervous system development), and patterns the surrounding mesoderm. It is crucial for proper vertebral column formation.

B. Prechordal Plate

Recap: A localized thickening of mesoderm (derived from the primitive node) just cranial to the notochord.

Critical Role: It is a vital signaling center for the development of the forebrain and craniofacial structures. It also helps organize the head mesenchyme.

C. Oropharyngeal Membrane (Buccopharyngeal Membrane)

Description: A small, circular area at the cranial end of the embryonic disc where the ectoderm and endoderm remain in direct contact, with no intervening mesoderm.

Significance: It forms the future opening of the mouth. It will eventually rupture (around Week 4) to connect the developing oral cavity with the pharynx.

D. Cloacal Membrane

Description: A similar small, circular area at the caudal end of the embryonic disc where the ectoderm and endoderm remain in direct contact, with no intervening mesoderm.

Significance: It forms the future opening of the anus and urogenital orifices. It will eventually rupture (around Week 7) to create these openings.

E. Body Axes Finalized

- Gastrulation definitively establishes the cranial-caudal (head-to-tail) and medial-lateral axes.

- The left-right axis also becomes established during gastrulation. This is due to molecular events around the primitive node (e.g., a "nodal flow" generated by cilia in the primitive node, influencing the asymmetrical expression of genes like Nodal and Lefty-1, which dictate left-sided development).

Clinical Note: Failure of this patterning can lead to conditions like situs inversus.

Primitive Streak Regression and Disappearance

The primitive streak, having served its essential purpose as the gateway for cell ingression and germ layer formation, is a transient structure. It does not persist throughout embryonic development.

-

1. Regression:

Beginning around Day 18-20, the primitive streak starts to shorten and move caudally (towards the tail end) relative to the embryonic disc.

-

2. Disappearance:

By the end of the fourth week (around Day 28), the primitive streak normally undergoes complete regression and disappears.

-

3. Significance of Regression:

Its timely regression is critical for proper embryonic development. The processes of gastrulation (formation of germ layers) and neurulation (formation of the neural tube) occur concurrently and in a cranio-caudal sequence, meaning the cranial regions differentiate while the caudal regions are still undergoing gastrulation. The primitive streak regresses as these caudal regions complete gastrulation and begin to form more mature structures.

8. Clinical Correlates: When Gastrulation Goes Awry

Given the complexity and critical timing of gastrulation, errors during this period can have severe consequences, often leading to major congenital malformations or early embryonic demise. These are some of the most significant clinical conditions associated with faulty gastrulation:

A. Sacrococcygeal Teratoma

Cause: This is the most common tumor in newborns. It results from the persistence of remnants of the primitive streak (pluripotent cells that failed to ingress or fully differentiate) in the sacrococcygeal region.

Nature: These primitive streak cells retain their pluripotency and can give rise to tissues from all three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm), resulting in a tumor that can contain hair, teeth, bone, cartilage, nervous tissue, glandular tissue, etc.

Location: Usually found at the base of the spine (sacrum and coccyx).

B. Caudal Dysgenesis (Sirenomelia)

Cause: This severe malformation is believed to result from an insufficient or premature regression of the primitive streak, or an insult that interferes with the caudal migration of mesoderm. This leads to a deficiency of caudal mesoderm.

- Partial or complete fusion of the lower limbs (giving a "mermaid-like" appearance, hence sirenomelia in severe cases).

- Vertebral anomalies (sacrum and coccyx are often absent or poorly formed).

- Genitourinary defects (e.g., renal agenesis, imperforate anus).

- Cardiac anomalies.

Association: Strongly associated with maternal diabetes.

C. Situs Inversus

Cause: While not a failure of germ layer formation, situs inversus is a condition where the normal left-right asymmetry of the organs is reversed (e.g., heart on the right, liver on the left). It can also be situs ambiguus or heterotaxy, where organs are randomly placed.

Mechanism: This condition results from defects in the molecular signaling pathways that establish left-right asymmetry during gastrulation, particularly around the primitive node (e.g., issues with nodal flow generated by cilia, or downstream gene expression like Nodal and Lefty-1).

D. Holoprosencephaly

Cause: While defects can occur later, some forms of holoprosencephaly (failure of the forebrain to divide into two hemispheres) are linked to problems in the prechordal plate and the signaling centers during early gastrulation that organize the head region.

Manifestations: Severe facial anomalies (cyclopia, proboscis), intellectual disability.

E. Anencephaly and Spina Bifida (Neural Tube Defects)

Cause: While technically occurring during neurulation (which immediately follows gastrulation), the proper formation and signaling from the notochord (derived during gastrulation) are crucial for inducing the overlying ectoderm to form the neural tube. Problems in notochord formation or signaling can predispose to these defects.

- Anencephaly: Failure of the neural tube to close at the cranial end, resulting in the absence of a major portion of the brain and skull.

- Spina Bifida: Failure of the neural tube to close at the caudal end, leading to various degrees of spinal cord and vertebral column defects.

9. Overall Significance of Gastrulation

To bring it all together:

-

Body Plan Establishment:

Gastrulation fundamentally establishes the three primary germ layers and the basic body plan of the organism, including all major body axes.

-

Cellular Differentiation:

It initiates the first major wave of cellular differentiation, transforming pluripotent epiblast cells into specific lineages.

-

Precursor to Organogenesis:

It lays the essential foundation upon which all subsequent organogenesis will occur. Without successful gastrulation, no further embryonic development is possible.

-

Vulnerability:

Due to its complex, coordinated cellular movements and signaling events, gastrulation is a highly sensitive period in development. Teratogens (agents causing birth defects) are particularly damaging during this window.

Organogenesis: From Germ Layers to Organs

Organogenesis is the dynamic developmental process where the three primary germ layers transform into specialized tissues and functional organs. This highly coordinated period begins around the end of week 3 and continues intensely through week 8, by which time all major organ systems have begun to form.

-

Timing:

Organogenesis spans from the third week (overlapping with gastrulation and neurulation, as initial organ precursors form) through to the eighth week of development.

-

Key Event:

During this period, the major organ systems begin to develop and take shape. By the end of the eighth week, all major organ systems are established, and the embryo looks distinctly human.

-

Significance:

This is an extremely critical period of development. Because so many fundamental structures are being laid down, the embryo is highly susceptible to teratogenic agents (factors causing birth defects) during this time.

General Principles of Organogenesis

Organogenesis isn't a random process; it's governed by several fundamental principles:

A. Inductive Interactions

One tissue signals to another to influence its development (e.g., notochord inducing neural plate).

Reciprocal Induction: Often, the induced tissue then signals back to the inducer, leading to a cascade of developmental events (e.g., eye development, limb development).

B. Cell Proliferation & Growth

Cells multiply rapidly through mitosis, increasing the size and complexity of tissues and organs.

C. Cell Migration

Cells move from their place of origin to their definitive location (e.g., neural crest cells, primordial germ cells, heart cells).

D. Cell Differentiation

Cells become specialized in structure and function (e.g., muscle cells, neurons, epithelial cells).

E. Apoptosis (Programmed Death)

Crucial for sculpting organs, forming lumens (hollow spaces), and removing unwanted structures (e.g., separating fingers and toes, forming the vaginal canal).

F. Patterning & Morphogenesis

Cells and tissues organize into specific shapes. Involves complex signaling (e.g., Hox genes for body axis patterning, FGFs for limb bud outgrowth).

Overview of Organ System Development (Week 3 - Week 8)

Here's a brief snapshot of what's happening with each major system during this crucial period.

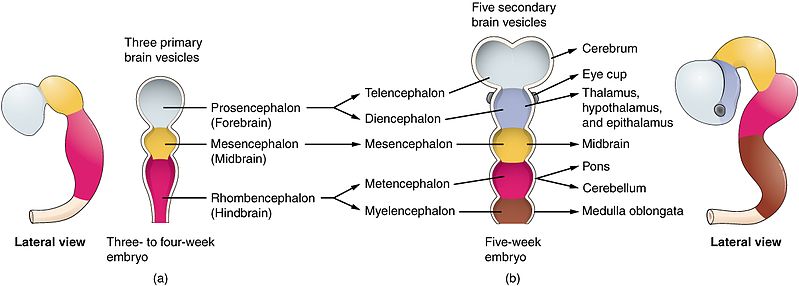

A. Nervous System

- Week 3: Neural plate forms, folds to neural tube.

- Week 4: Neural tube closes (neuropores), primary brain vesicles form, differentiation into alar/basal plates.

- Weeks 5-8: Secondary brain vesicles form, significant folding, cranial nerves emerge, neural crest cells form ganglia. Early reflexes may develop.

B. Cardiovascular System

- Week 3: Angiogenesis begins, two endocardial heart tubes form and begin to fuse.

- Week 4: Heart tubes fuse to single pulsating tube (Day 22). Heart beats, circulation starts. Cardiac looping (S-shape).

- Weeks 5-8: Septation of atria/ventricles, formation of great vessels. By Week 8, four-chambered heart is largely complete.

C. Musculoskeletal System

- Week 4: Somites differentiate (sclerotome, myotome, dermatome). Limb buds appear.

- Weeks 5-8: Cartilaginous bone models form, muscle masses differentiate, joints form, digits separate (apoptosis).

D. Gastrointestinal System

- Week 4: Gut tube established (folding). Membranes rupture.

- Weeks 5-8: Esophagus, stomach, liver, pancreas develop. Midgut undergoes physiological herniation into umbilical cord.

E. Urogenital System

- Week 4: Pronephros forms and degenerates.

- Week 5: Mesonephros forms (brief function).

- Week 6: Metanephros (definitive kidney) begins.

- Weeks 7-8: Kidney ascends, external genitalia begin developing (sex not distinct yet).

F. Respiratory System

- Week 4: Respiratory diverticulum (lung bud) forms.

- Weeks 5-8: Lung buds branch repeatedly to form bronchi and bronchioles.

G. Integumentary

Week 5-8: Epidermis/dermis differentiate. Hair follicles and glands start to form.

H. Special Sense Organs

Week 4: Optic/Otic placodes appear.

Week 5-8: Lens vesicle, optic cup, ear structures.

I. Development from the Ectoderm (Outer Layer)

The ectoderm gives rise to structures that maintain contact with the outside world.

Neurulation (Formation of the Nervous System)

The notochord (from the mesoderm) induces the overlying ectoderm to form the neural plate, which folds into the neural tube. This tube becomes the brain and spinal cord (CNS).

Neural Crest Cells break off during this process to form the peripheral nervous system, pigment cells, and parts of the face, skull, and heart.

Epidermal Ectoderm

The remaining ectoderm forms the epidermis and its derivatives, including: hair, nails, sweat glands, mammary glands, tooth enamel, and the lens of the eye.

II. Development from the Mesoderm (Middle Layer)

The mesoderm gives rise to structures that support and move the body, and circulate fluids.

Paraxial Mesoderm (forms Somites)

- Sclerotome: Vertebrae and ribs (skeleton).

- Myotome: Skeletal muscles.

- Dermatome: Dermis of the skin.

Intermediate Mesoderm

Forms the urogenital system: kidneys, gonads (ovaries/testes), and their associated ducts.

Lateral Plate Mesoderm

Forms the body cavities, connective tissues of the body wall and limbs, smooth muscle of organs, and the entire circulatory system (heart, blood vessels, blood cells).

III. Development from the Endoderm (Inner Layer)

The endoderm primarily forms the epithelial lining of internal structures.

Gut Tube & Respiratory System

The endoderm folds to form a tube, giving rise to the epithelial lining of the entire digestive tract (pharynx to large intestine) and the respiratory system (trachea, bronchi, lungs).

Associated Glands & Organs

Forms the functional tissues of the liver, pancreas, gallbladder, thyroid, parathyroid, and thymus, as well as the lining of the urinary bladder.

The Embryonic Period Concludes (End of Week 8)

- By the end of the eighth week (approx. 56 days post-fertilization), the embryonic period ends, and the fetal period begins.

- All major organ systems are now established, though many are not yet fully functional.

- The embryo is about 3 cm long (crown-rump length) and weighs around 4-5 grams.

- It now has a distinctly human appearance, with discernible limbs, digits, and facial features.

Clinical Correlates: Teratogens During Organogenesis

Because organogenesis is the period of rapid development and differentiation of all major systems, it is also the period of greatest sensitivity to teratogens. Exposure to harmful agents during these weeks can lead to severe congenital malformations.

- Thalidomide: Caused severe limb reduction defects (amelia, phocomelia) when taken during Weeks 4-6.

- Alcohol: Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD), causing facial anomalies, intellectual disabilities.

- Rubella Virus: Causes cataracts, heart defects, deafness.

- Radiation: Can cause microcephaly, intellectual disability.

Understanding the timeline of organogenesis is crucial for identifying when exposure to a teratogen would have its most devastating effect on a particular organ system.

So means we start from Nervous System. Neurulation Next

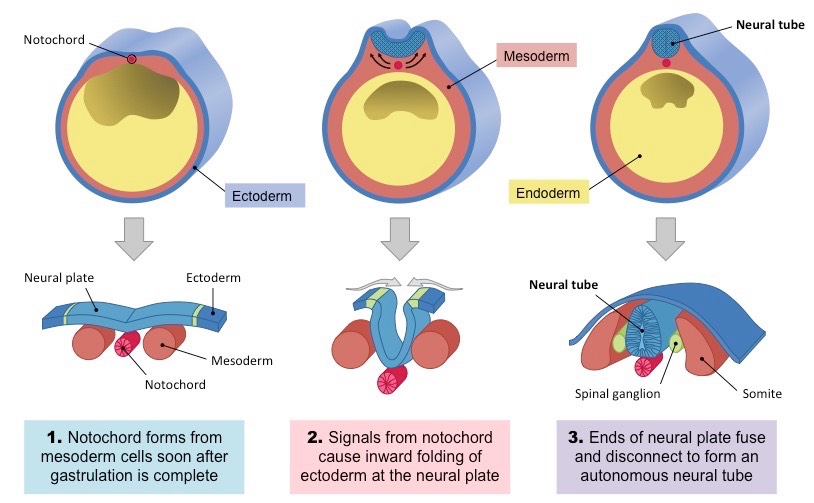

What is Neurulation?

Neurulation is the process by which the neural plate folds to form the neural tube, which subsequently develops into the brain and spinal cord. It is the first step in the formation of the Central Nervous System (CNS). This process is critically important as the CNS acts as the control center for virtually all body functions.

When does it occur?

- Timing: Primarily takes place during the third and fourth weeks of embryonic development.

- Key Event: It directly follows and is critically dependent upon the formation of the notochord during gastrulation.

Why is it so significant?

- Foundation of the CNS: It creates the precursor structure for the entire brain and spinal cord.

- Inductive Event: It's a classic example of embryonic induction, where one tissue (the notochord) signals to another (the overlying ectoderm) to change its fate and develop into a new structure.

- Vulnerability: Due to the complex movements and cell shape changes involved, neurulation is highly susceptible to disruptions, leading to a class of birth defects known as Neural Tube Defects (NTDs).

Neurulation is the pivotal process by which the neural plate folds and fuses to form the neural tube, the embryonic precursor to the central nervous system (CNS)—the brain and the spinal cord. This is one of the first major events of organogenesis.

This process begins during the third week of development (around day 18) and is completed by the end of the fourth week (around day 28). It occurs in the dorsal ectoderm, directly above the notochord.

Key Players and Precursors

Notochord (from Mesoderm)

The master conductor. This rod-like structure secretes signaling molecules that act as neural inducers.

Ectoderm

The outermost germ layer that responds to the notochord's signals, differentiating into the nervous system and skin.

The Role of the Notochord: The Master Inducer

Before neurulation can even begin, the newly formed notochord (from gastrulation) must be in place. The notochord is the primary inducer of neurulation.

- Location: The notochord lies in the midline, directly beneath the ectoderm and above the endoderm.

- Signaling: The notochord secretes various signaling molecules, most notably Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) and Noggin/Chordin (BMP antagonists).

- Induction: These signals induce the overlying ectoderm to differentiate into neuroectoderm, forming the neural plate. Without the notochord, the ectoderm would continue to develop into epidermis.

Stages of Neurulation

Neurulation is divided into two main phases, with primary neurulation forming the majority of the CNS.

1. Primary Neurulation

a. Formation of the Neural Plate (Day 18)

The notochord induces the overlying ectoderm to thicken and flatten, forming an elongated structure called the neural plate. The cells of this plate are now called neuroectoderm.

- Origin: The ectoderm that lies directly dorsal to the notochord.

- Transformation: Under the inductive influence of the notochord, this region of the ectoderm thickens and flattens to form a slipper-shaped, elongated structure called the neural plate.

- Location: Extends cranially from the primitive node towards the oropharyngeal membrane.

- Cell Type: Cells are now called neuroectoderm. They are taller and more columnar than the surrounding surface ectoderm.

b. Formation of Neural Groove & Folds (Day 19-20)

The lateral edges of the neural plate elevate to form neural folds, while the central region sinks to create the neural groove. Hinge points form, causing the plate to bend inward.

- Elevation: The lateral edges of the neural plate elevate, forming neural folds.

- Neural Groove: As the neural folds elevate, a central depression forms between them, known as the neural groove.

- U-shape: This process gives the neural plate a U-shaped appearance.

c. Fusion of Neural Folds (Day 20-22)

The neural folds move towards the midline and begin to fuse, starting in the future cervical (neck) region. This fusion proceeds in both directions, like a zipper.

- Approximation & Fusion: Neural folds meet in the midline and fuse, starting in the cervical region (future neck) and proceeding cranially and caudally.

- Neural Tube Formation: Seals off the neural groove, creating a hollow, tube-like structure.

- Separation: The neural tube detaches from the overlying surface ectoderm, which fuses to form the continuous epidermis.

-

Closure Points:

- Anterior (Cranial) Neuropore: Closes around Day 25.

- Posterior (Caudal) Neuropore: Closes around Day 27-28.

d. Formation of the Neural Tube & Neural Crest

As the folds fuse, the neural tube is pinched off from the surface ectoderm, which then fuses above it to become the epidermis. At the crests of the fusing folds, a unique population of neural crest cells delaminates and begins to migrate.

e. Closure of Neuropores

The open ends of the neural tube, the neuropores, are the last to close. The anterior (cranial) neuropore closes around day 25, and the posterior (caudal) neuropore closes around day 28.

Differentiation of the Neural Tube: Brain and Spinal Cord Development

Once formed, the neural tube doesn't remain a simple, uniform structure. It rapidly undergoes regionalization and differentiation into the distinct parts of the central nervous system. This process begins even as the neural tube is closing.

A. Regionalization along the Cranio-Caudal Axis:

The neural tube quickly develops distinct regions along its length, largely due to signaling molecules (like FGFs, Wnt, and retinoic acid gradients) that establish anterior-posterior patterning.

The cranial (anterior) two-thirds of the neural tube expands dramatically and forms three primary brain vesicles by the end of Week 4:

- Prosencephalon (Forebrain): Will further divide into the telencephalon (cerebral hemispheres) and diencephalon (thalamus, hypothalamus).

- Mesencephalon (Midbrain): Remains a single vesicle.

- Rhombencephalon (Hindbrain): Will further divide into the metencephalon (pons, cerebellum) and myelencephalon (medulla oblongata).

These vesicles will then undergo further folding and differentiation to form the complex structures of the adult brain.

The caudal (posterior) one-third of the neural tube remains relatively narrow and develops into the spinal cord.

B. Regionalization along the Dorso-Ventral Axis:

Within the neural tube, particularly in the spinal cord and brainstem regions, specific cell types differentiate depending on their dorsal or ventral position. This is another example of inductive signaling:

Dorsal/Sensory Side (Alar Plate)

Induced by signals from the surface ectoderm (like BMPs and Wnt). Cells here will give rise to sensory neurons and interneurons.

Ventral/Motor Side (Basal Plate)

Induced by signals from the notochord and floor plate (like Sonic Hedgehog - Shh). Cells here will give rise to motor neurons and interneurons.

Sulcus Limitans: A longitudinal groove on the inner surface of the neural tube that separates the alar and basal plates.

C. Histological Differentiation:

The wall of the early neural tube consists of neuroepithelial cells. These rapidly divide and differentiate to form:

- Neuroblasts: Precursors to neurons.

- Glioblasts: Precursors to glial cells (astrocytes, oligodendrocytes).

- Ependymal Cells: Line the central canal of the spinal cord and the ventricles of the brain.

2. Secondary Neurulation

While primary neurulation forms most of the CNS, the very caudal (tail end) part of the spinal cord is formed by a different process. This involves the condensation of mesenchyme cells in the tail bud, which then cavitate and fuse with the primary neural tube.

Folding of the Embryo

1. Introduction: From Flat Disc to 3D Body

- Timing: Embryonic folding occurs primarily during the fourth week of development.

- Purpose: To convert the flat, trilaminar embryonic disc into a more cylindrical, three-dimensional body form. This brings structures into their correct anatomical positions, establishes the major body cavities, and incorporates parts of the yolk sac into the embryo proper.

- Key Movements: Folding occurs simultaneously in two main directions:

- Cephalocaudal Folding: (Head-Tail) along the longitudinal axis.

- Lateral Folding: (Transverse) along the horizontal axis.

2. Cephalocaudal (Longitudinal) Folding: The Head and Tail Folds

Driven primarily by the rapid growth of the neural tube, particularly the developing brain vesicles at the cranial end.

A. Cranial (Head) Fold

Mechanism: Brain vesicles grow rapidly and extend dorsally, then fold ventrally over the cardiac area.

- Neural Tube: Forebrain moves cranially, then ventrally.

- Oropharyngeal Membrane: Moves ventrally and caudally to future mouth region.

- Cardiac Area: Pulled ventrally and caudally into definitive chest position.

- Septum Transversum: Moves ventrally and caudally, ending up caudal to the heart (diaphragm precursor).

- Foregut Formation: Part of yolk sac incorporated as the foregut.

B. Caudal (Tail) Fold

Mechanism: Caudal end of neural tube and somites grow; primitive streak regresses.

- Neural Tube: Caudal end moves dorsally, then ventrally.

- Cloacal Membrane: Carried ventrally and cranially to anal/urogenital region.

- Connecting Stalk: Moves from caudal to ventral position (future umbilical cord).

- Hindgut Formation: Part of yolk sac incorporated as the hindgut.

3. Lateral (Transverse) Folding: Formation of the Body Walls

Driven by the rapid growth of somites and the neural tube.

Mechanism: The left and right lateral edges of the trilaminar disc fold downwards and inwards towards the midline.

Consequences:- Body Wall Formation: Lateral plate mesoderm and ectoderm form ventrolateral body walls.

- Midgut Formation: Central portion of yolk sac incorporated as midgut. Connects to yolk sac via vitelline duct.

- Gut Tube Formation: Foregut, midgut, and hindgut form primitive gut tube suspended in coelom.

- Formation of Body Cavities: Intraembryonic coelom transforms into pericardial, pleural, and peritoneal cavities.

- Fusion of Ventral Body Wall: Lateral folds meet and fuse in midline (except at umbilical cord).

- Amniotic Cavity Envelopment: Amnion completely surrounds the embryo; fluid-filled protection established.

4. Summary of Folding Outcomes

By the end of the fourth week:

- Flat disc converted to cylindrical embryo.

- Primitive gut tube formed.

- Oropharyngeal/Cloacal membranes in ventral position.

- Heart located in thoracic region.

- Septum transversum positioned for diaphragm.

- Connecting stalk positioned ventrally.

- Body cavities established.

- Embryo enveloped by amnion.

Clinical Correlates: Body Wall Defects

Failures in embryonic folding, particularly lateral folding and ventral body wall closure, can lead to:

- Gastroschisis: Defect in anterior abdominal wall (usually right of umbilicus). Intestines protrude into amniotic cavity without a sac.

- Omphalocele: Protrusion of abdominal contents into umbilical cord, covered by a sac of amnion/peritoneum. Result of midgut failure to return.

- Ectopia Cordis: Failure of thoracic wall closure; heart is partially/completely outside the chest.

- Bladder Exstrophy: Failure of lower abdominal/anterior bladder wall closure; bladder mucosa exposed.

Derivatives of the Neural Tube

The neural tube, the primary structure formed during neurulation, differentiates into the entire Central Nervous System (CNS).

Brain

The anterior (cranial) part of the tube undergoes significant expansions to form the primary brain vesicles, which further differentiate into all adult brain structures (cerebrum, cerebellum, brainstem, etc.).

Spinal Cord

The posterior (caudal) part of the neural tube forms the spinal cord.

Neural Canal

The hollow lumen inside the tube becomes the ventricular system of the brain and the central canal of the spinal cord, responsible for circulating cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Formation of the Neural Crest Cells: The "Fourth Germ Layer"

During the process of neural fold elevation and fusion, a very special population of cells emerges.

Origin: As the neural folds elevate and fuse, cells at the crest (apex) of the neural folds undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and delaminate.

Migration: These cells, now called neural crest cells, migrate extensively throughout the embryo.

By the end of primary neurulation, we have a fully formed neural tube, destined to become the brain and spinal cord, and a migrating population of neural crest cells that will contribute to many other body systems.

Derivatives of the Neural Crest Cells

Neural crest cells are often called the "fourth germ layer" due to their remarkable migratory abilities and the vast array of diverse tissues they form. After delaminating from the neural folds, they travel extensively throughout the embryo.

Peripheral Nervous System (PNS)

- Sensory & Autonomic Neurons

- Schwann Cells

Endocrine & Pigment

- Adrenal Medulla

- Melanocytes (pigment cells)

Craniofacial Structures

- Bones & cartilage of face/skull

- Dentin of teeth

Cardiac Development

- Outflow tract of the heart

Clinical Correlates: Neural Tube Defects (NTDs)

Neural Tube Defects (NTDs) are among the most common and serious birth defects. They result from the failure of the neural tube to close properly at specific points along its length.

A. Factors Contributing to NTDs:

- Folic Acid Deficiency: This is by far the most well-established and preventable cause. Adequate maternal folic acid intake (especially preconception and during the first trimester) is crucial.

- Genetics: Some genetic predispositions exist.

- Maternal Diabetes: Poorly controlled maternal diabetes increases the risk.

- Certain Medications: Some anticonvulsants (e.g., valproic acid) increase risk.

- Maternal Obesity.

- Hyperthermia: Exposure to high temperatures during early pregnancy.

B. Types of NTDs:

- Cause: Failure of the anterior (cranial) neuropore to close (around Day 25).

- Manifestations: Absence of a major portion of the brain, skull, and scalp. The brain tissue that is present is often malformed and exposed.

- Prognosis: Incompatible with life; affected fetuses are stillborn or die shortly after birth.

Cause: Failure of the posterior (caudal) neuropore to close (around Day 27-28), or more generally, defective closure of the vertebral arches of the spinal column.

Mildest form. Incomplete fusion of vertebral arches, usually asymptomatic. Identified by hair patch/dimple.

Meninges protrude through the defect forming a fluid-filled sac. Spinal cord remains in canal. Fewer neurological deficits.

Meninges AND spinal cord protrude. Significant deficits: paralysis, loss of sensation, hydrocephalus (Chiari II), bowel/bladder dysfunction.

- Cause: Defect in closure of neural tube AND skull, resulting in protrusion of brain tissue/meninges.

- Manifestations: Varying degrees of neurological impairment.

C. Prevention of NTDs:

Folic Acid Supplementation: The most effective preventative measure. Women of childbearing age are recommended to take 400 micrograms (0.4 mg) daily, starting at least one month before conception. Higher doses (e.g., 4 mg) for high-risk cases.

Germ Disc to Neurulation

Test your knowledge with these 30 questions.

Germ Disc to Neurulation Quiz

Question 1/30

Quiz Complete!

Here are your results, .

Your Score

27/30

90%