Reproductive Cycles & Gametogenesis cells

Gametogenesis

Gametogenesis is the fundamental biological process where a diploid cell (2n), specifically a primordial germ cell, undergoes meiosis to form a haploid gamete (n). In simpler terms, it's the creation of sex cells.

In males, this process is called spermatogenesis and results in the production of spermatozoa (sperm). In females, it is called oogenesis, which leads to the formation of an ovum (egg).

Purpose of Gametogenesis

To produce genetically diverse haploid gametes (sperm and egg) that are ready for fertilization. The fusion of these cells forms a diploid zygote, initiating the development of a new, genetically unique individual.

Where It Happens (The Gonads)

- In Males: The testes

- In Females: The ovaries

Common Terms to Know First

Understanding the following vocabulary is essential for grasping the concepts of gametogenesis.

- Diploid (2n) vs. Haploid (n)

- Diploid cells contain two complete sets of chromosomes (46 in humans), one from each parent. Most body cells are diploid. Haploid cells contain only a single set of chromosomes (23 in humans). Gametes are haploid.

- Primordial Germ Cells (PGCs)

- The earliest recognizable precursor cells for gametes. They originate outside the gonads during embryonic development and migrate into them.

- Mitosis

- Standard cell division that produces two identical diploid daughter cells. Used to multiply the number of precursor germ cells before meiosis begins.

- Meiosis

- A specialized two-stage cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, producing four genetically unique haploid cells from one diploid cell.

-

Meiosis I: The "reductional division" where homologous chromosome pairs are separated, making the cells haploid.

Meiosis II: Similar to mitosis, where sister chromatids are separated.

1. The Fundamental Purpose of Reproduction

At its core, reproduction is the biological process by which new individual organisms are produced from their parents. It is a defining characteristic of all known life, and it ensures the continuation of a species from one generation to the next. Without reproduction, a species would become extinct.

A. Asexual vs. Sexual Reproduction

There are two primary modes of reproduction, each with distinct characteristics and evolutionary implications:

Asexual Reproduction

Definition: Involves a single parent producing offspring that are genetically identical to itself. There is no fusion of gametes.

- Binary Fission: (e.g., bacteria, amoeba) A single cell divides into two identical daughter cells.

- Budding: (e.g., yeast, hydra) A new organism grows out from the body of the parent.

- Fragmentation: (e.g., starfish, planaria) A parent organism breaks into fragments, and each fragment develops into a new individual.

- Vegetative Propagation: (e.g., plants) New plants grow from parts of the parent plant (stems, leaves, roots).

- Parthenogenesis: (e.g., some insects, reptiles) Development of an embryo from an unfertilized egg.

- Rapid population growth: Can produce many offspring quickly.

- No need for a mate: Beneficial in sparsely populated or harsh environments.

- Energy efficient: Less energy investment compared to finding a mate and gamete production/fertilization.

- Successful in stable environments: If the parent is well-adapted, offspring will also be well-adapted.

- Lack of genetic diversity: Offspring are clones, making the entire population vulnerable to environmental changes, diseases, or new predators.

- Limited adaptation: Slower evolution due to lack of variation.

Sexual Reproduction

Definition: Involves two parents contributing genetic material to produce offspring that are genetically unique. This typically involves the fusion of two specialized reproductive cells called gametes (sperm and egg).

- Fertilization: The fusion of male and female gametes to form a zygote.

- Meiosis: A specialized type of cell division that produces haploid gametes from diploid germline cells (which we will delve into next!).

- Genetic diversity: Generates new combinations of alleles through meiosis (crossing over, independent assortment) and the random fusion of gametes. This variation is the raw material for natural selection.

- Adaptation: Increased diversity allows populations to adapt to changing environments, resist diseases, and evolve.

- Removal of deleterious mutations: Sexual reproduction can help purge harmful mutations from a population more effectively over time.

- Slower reproduction rate: Typically fewer offspring produced.

- Energy intensive: Requires finding a mate, courtship, and often parental care.

- Risk of disease transmission: Can facilitate the spread of sexually transmitted diseases.

In humans and most complex animals, sexual reproduction is the primary mode, emphasizing the crucial role of genetic diversity in long-term species survival and adaptation.

2. The Role of Meiosis in Gametogenesis

Sexual reproduction relies on the fusion of two gametes, each contributing a set of chromosomes. To ensure that the offspring ends up with the correct number of chromosomes (and not double the amount with each generation), a specialized cell division called Meiosis is essential.

A. Overview of Chromosome Number:

- Diploid (2n): Cells that contain two sets of homologous chromosomes (one set inherited from each parent). Somatic (body) cells are diploid. In humans, 2n = 46 chromosomes.

- Haploid (n): Cells that contain only one set of chromosomes. Gametes (sperm and egg) are haploid. In humans, n = 23 chromosomes.

B. What is Meiosis?

Meiosis is a two-step cell division process that transforms one diploid cell into four genetically distinct haploid cells (gametes). It is unique to sexually reproducing organisms and has two main goals:

- Reduce the chromosome number by half: From diploid (2n) to haploid (n).

- Generate genetic diversity: Through processes we've touched upon before, and will elaborate here.

C. Stages of Meiosis:

Meiosis involves two consecutive cell divisions, Meiosis I and Meiosis II, each with prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase stages.

Meiosis I (Reductional Division)

Homologous chromosomes separate.

- Prophase I:

- Chromosomes condense and become visible.

- Synapsis: Homologous chromosomes pair up, forming bivalents (or tetrads, as they consist of four chromatids).

- Crossing Over: Non-sister chromatids of homologous chromosomes exchange genetic material at points called chiasmata. This is a critical event for genetic recombination and creating new allele combinations on chromatids.

- Nuclear envelope breaks down; spindle fibers form.

- Metaphase I:

- Homologous chromosome pairs (bivalents) align randomly at the metaphase plate.

- Independent Assortment: The orientation of each homologous pair is random and independent of other pairs. This further shuffles genetic information.

- Anaphase I: Homologous chromosomes separate and move to opposite poles of the cell. Sister chromatids remain attached.

- Telophase I & Cytokinesis:

- Chromosomes decondense (partially).

- Nuclear envelopes may reform.

- Cytokinesis divides the cytoplasm, resulting in two haploid cells (each chromosome still consists of two sister chromatids).

Meiosis II (Equational Division)

Sister chromatids separate. This division is very similar to mitosis.

- Prophase II: Chromosomes condense again (if they decondensed). Nuclear envelope breaks down; spindle fibers form.

- Metaphase II: Chromosomes (each still with two sister chromatids) align individually at the metaphase plate.

- Anaphase II: Sister chromatids separate and move to opposite poles, now considered individual chromosomes.

- Telophase II & Cytokinesis:

- Chromosomes decondense.

- Nuclear envelopes reform.

- Cytokinesis divides the cytoplasm, resulting in a total of four haploid cells, each with single, unreplicated chromosomes.

D. How Meiosis Contributes to Genetic Variation:

Meiosis is a powerhouse of genetic diversity, achieving it through three main mechanisms:

- Crossing Over (Prophase I):

- Exchange of genetic material between non-sister chromatids of homologous chromosomes.

- Breaks old combinations of alleles and creates new ones on the chromatids.

- For example, if a chromosome initially carried alleles AB, after crossing over it might carry Ab or aB.

- Independent Assortment of Homologous Chromosomes (Metaphase I):

- The random orientation of homologous pairs at the metaphase plate means that the maternal and paternal chromosomes are segregated into daughter cells independently of other pairs.

- For an organism with 'n' pairs of chromosomes, there are 2^n possible combinations of chromosomes in the resulting gametes. In humans (n=23), this is over 8 million (2^23) possibilities!

- Random Fertilization:

- The fusion of any one male gamete with any one female gamete further increases the number of possible genetic combinations in the zygote. The odds of two children from the same parents being genetically identical (except for identical twins) are astronomically small.

Spermatogenesis: The Formation of Sperm

Spermatogenesis is the continuous process of producing sperm (male gametes) in the testes. It's a marvel of biological engineering, designed to create a vast number of highly specialized cells capable of fertilization.

Timing

Begins at puberty (10-16 years) and continues throughout adult life.

Location

Within the seminiferous tubules of the testes.

Quantity

Enormous output of ~200 million sperm per day.

The Blood-Testis Barrier: Protecting the Sperm

Sertoli cells form a critical barrier that prevents substances from the blood from harming developing sperm. It also shields the genetically different sperm from the male's own immune system, which would otherwise recognize them as foreign and attack them.

Terms in Spermatogenesis

Before diving into the process, it's crucial to understand the key cell types involved.

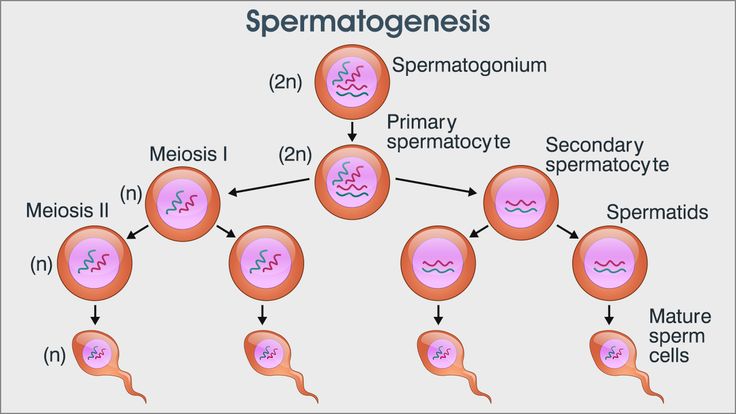

- Spermatogonium

- The diploid (2n) stem cells in the testes that initiate the process.

- Primary Spermatocyte

- A diploid (2n) cell that has grown and is ready to undergo Meiosis I.

- Secondary Spermatocyte

- The two haploid (n) cells resulting from Meiosis I.

- Spermatid

- The four haploid (n), round, immature cells resulting from Meiosis II.

- Spermiogenesis

- The final maturation stage where spermatids are physically remodeled into spermatozoa. This is not cell division.

- Spermatozoon (Sperm)

- The mature, motile male gamete with a head (containing the nucleus and acrosome), midpiece, and tail.

The Stages of Spermatogenesis

The journey from a basic stem cell to four spermatids involves a carefully orchestrated sequence of mitosis and meiosis.

1. Proliferation (Mitosis)

Diploid spermatogonia divide by mitosis to create a pool of precursor cells. Some remain as stem cells for continuous production, while others (Type B) are committed to becoming sperm.

2. Growth

The Type B spermatogonium grows and replicates its DNA, becoming a primary spermatocyte (still 2n, but with duplicated chromosomes).

3. First Meiotic Division (Meiosis I)

The primary spermatocyte divides, separating homologous chromosomes. This results in two haploid secondary spermatocytes (n).

4. Second Meiotic Division (Meiosis II)

Each secondary spermatocyte divides again, separating sister chromatids. This produces a total of four haploid spermatids (n).

Final Maturation and Journey

The spermatids created through meiosis are not yet functional. They must undergo a final transformation and journey to become capable of fertilization.

Spermiogenesis: The Transformation

During this dramatic remodeling phase, the round spermatid:

- Forms a head with a condensed nucleus and an enzyme-filled acrosome cap.

- Develops a midpiece packed with mitochondria for energy.

- Grows a long tail (flagellum) for movement.

- Sheds most of its cytoplasm to become lightweight.

Once this is complete, the cells are called spermatozoa and are released into the tubule lumen in a process called spermiation.

The Journey to Maturity

Immature sperm travel from the seminiferous tubules through the rete testis and into the epididymis. The epididymis is the "finishing school" where sperm spend several weeks to gain full motility and the ability to fertilize an egg. It also serves as the primary storage site.

Capacitation: The Final Activation

Even after leaving the epididymis, sperm are not ready. Capacitation is a final series of biochemical changes that occurs within the female reproductive tract. It destabilizes the sperm's acrosome membrane, making it capable of releasing its enzymes to penetrate the egg. Without capacitation, fertilization cannot occur.

3. Detail the Process of Spermatogenesis (Male Gamete Formation)

Spermatogenesis is the process by which male primordial germ cells (spermatogonia) develop into mature spermatozoa (sperm). This continuous process occurs in the male gonads, the testes, specifically within the walls of the seminiferous tubules. It begins at puberty and continues throughout a male's life.

A. Site of Spermatogenesis:

Seminiferous Tubules: Coiled tubes located within the testes. These tubules contain two main cell types critical for sperm production:

- Spermatogenic cells: These are the cells undergoing meiosis and differentiation to become sperm.

- Sertoli cells (or sustentacular cells): These are "nurse cells" that support, protect, and nourish the developing spermatogenic cells. They also form the blood-testis barrier and produce hormones (like inhibin).

- Leydig cells (or interstitial cells): Located in the connective tissue between the seminiferous tubules, these cells produce androgens, primarily testosterone, which is essential for spermatogenesis and the development of male secondary sexual characteristics.

B. Stages of Spermatogenesis:

Spermatogenesis is a highly organized process involving three main phases: mitosis, meiosis, and spermiogenesis. It takes approximately 64-72 days in humans.

1. Proliferation (Mitosis)

Spermatogonia (2n): These are diploid (2n=46) stem cells located in the outermost layer of the seminiferous tubule wall, near the basement membrane. Throughout life, spermatogonia continually divide by mitosis. Some daughter cells remain as spermatogonia to maintain the stem cell pool, while others differentiate into primary spermatocytes.

2. Meiosis

- Primary Spermatocyte (2n): A diploid cell that enters Meiosis I. Undergoes Meiosis I to produce two secondary spermatocytes.

- Secondary Spermatocyte (n): Each is haploid (n=23), but chromosomes still consist of two sister chromatids. Each undergoes Meiosis II to produce two spermatids.

- Spermatid (n): Each is haploid (n=23) and now has single, unreplicated chromosomes. They are round cells and not yet motile.

Summary of Meiosis in Spermatogenesis:

- One primary spermatocyte (2n) yields two secondary spermatocytes (n).

- Two secondary spermatocytes (n) yield four spermatids (n).

- Therefore, one primary spermatocyte ultimately produces four haploid spermatids.

3. Spermiogenesis (Differentiation)

This is the final stage where spermatids undergo a remarkable morphological transformation into mature, motile spermatozoa (sperm). No further cell division occurs here.

Key changes include:

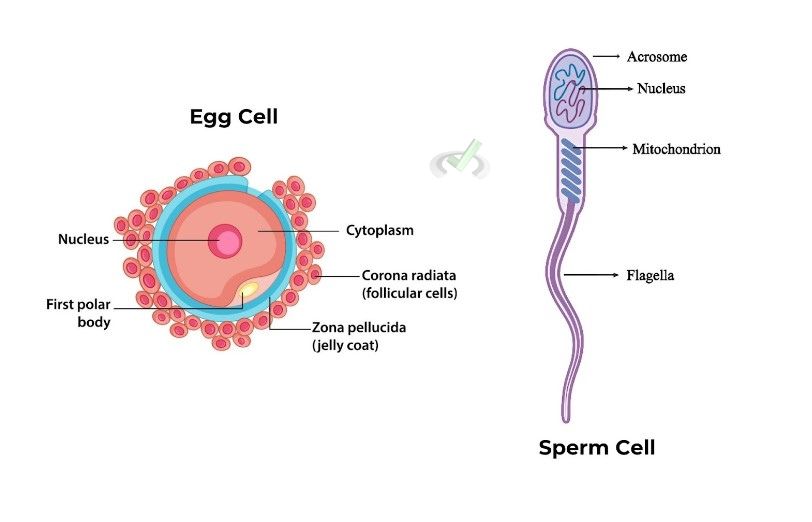

- Head Formation: The nucleus condenses and flattens. The acrosome, a cap-like organelle derived from the Golgi apparatus, forms over the anterior part of the nucleus. The acrosome contains enzymes vital for penetrating the egg.

- Midpiece Formation: Mitochondria cluster around the base of the flagellum, forming the midpiece, which provides ATP for flagellar movement.

- Tail (Flagellum) Formation: Microtubules organize to form a long flagellum, providing motility.

- Cytoplasm Shedding: Most excess cytoplasm is shed, making the sperm streamlined for movement.

C. Mature Spermatozoon Structure:

A mature sperm cell is highly specialized for delivering male genetic material to the egg:

- Head: Contains the condensed haploid nucleus (genetic material) and the acrosome.

- Midpiece: Contains numerous mitochondria to power the flagellum.

- Tail (Flagellum): Provides motility, allowing the sperm to swim towards the egg.

D. Timing of Spermatogenesis:

- Begins at puberty due to the surge in testosterone.

- Continuous process throughout a male's reproductive life, though production may decrease with age.

- The entire cycle from spermatogonium to mature spermatozoon takes approximately 64-72 days.

Oogenesis: The Formation of the Ovum

Oogenesis is the biological process by which ova (egg cells) are produced in the ovaries. It begins with primordial germ cells that colonise the cortex of the primordial gonad, multiplying to a peak of approximately 7 million by mid-gestation before a process of cell death (atresia) begins.

Crucially, Meiosis I begins before birth, forming all the primary oocytes a female will ever have. This means there is a finite supply of ova.

Key Differences from Spermatogenesis

- Timing: Starts before birth, pauses, and ends at menopause.

- Quantity: Produces only one large, functional ovum and smaller polar bodies per division.

- Nature: A cyclic process after puberty, releasing one egg per menstrual cycle.

Terms in Oogenesis

Understanding the unique vocabulary of female gamete formation is essential.

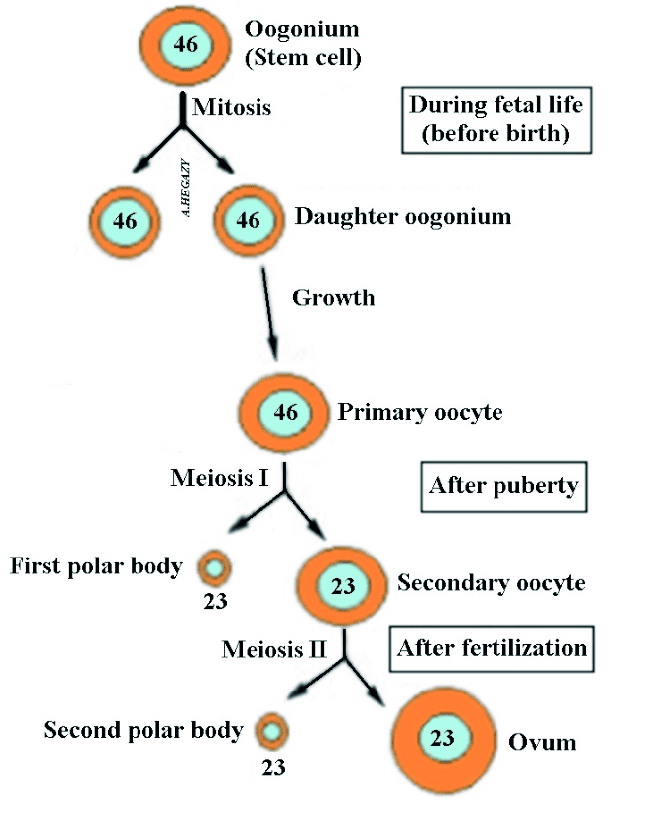

- Oogonium

- The diploid (2n) stem cells in the fetal ovary that divide by mitosis.

- Primary Oocyte

- A diploid (2n) cell that enters Meiosis I but is arrested in Prophase I before birth.

- Secondary Oocyte

- The large, haploid (n) cell produced after Meiosis I is completed. It is arrested in Metaphase II and is the cell released during ovulation.

- Ovum

- The mature haploid (n) egg cell, formed only after the secondary oocyte is fertilized by a sperm, triggering the completion of Meiosis II.

- Polar Body

- A small, non-functional haploid cell produced during unequal divisions, serving to discard excess chromosomes.

- Ovarian Follicle (e.g., Graafian Follicle)

- The functional unit of the ovary, a fluid-filled sac containing the developing oocyte and hormone-producing cells.

The Stages of Oogenesis

Oogenesis is a prolonged process that occurs in three distinct phases, punctuated by long periods of arrest.

Phase 1: Before Birth (Fetal Ovary)

Oogonia multiply via mitosis. Many differentiate into primary oocytes, which then begin Meiosis I but are immediately arrested in Prophase I. A female is born with her lifetime supply of these arrested primary oocytes.

Phase 2: From Puberty to Menopause (Monthly Cycles)

Each month, hormonal signals cause a primary oocyte to complete Meiosis I. This division is unequal, producing one large, haploid secondary oocyte and one small first polar body. The secondary oocyte then begins Meiosis II but is arrested again in Metaphase II. This is the stage at which ovulation occurs.

Phase 3: Only Upon Fertilization

Meiosis II is only completed if the secondary oocyte is fertilized by a sperm. The sperm's entry triggers the final division, producing one large, mature ovum and a tiny second polar body. If fertilization does not occur, the arrested secondary oocyte degenerates.

Follicular Development

The maturation of the oocyte happens within a structure called the ovarian follicle, which also undergoes its own development.

Pre-antral Stage: The primary oocyte is surrounded by follicular cells that grow and secrete glycoproteins, forming the zona pellucida.

Antral Stage: A fluid-filled space called the antrum forms, creating a secondary follicle.

Preovulatory Stage: Triggered by an LH surge, Meiosis I completes, and the mature follicle (Graafian follicle) prepares for ovulation.

4. Detail the Process of Oogenesis (Female Gamete Formation)

Oogenesis is the process by which female primordial germ cells (oogonia) develop into mature ova (eggs). Unlike spermatogenesis, oogenesis is a discontinuous process, beginning before birth and completing only after fertilization. It occurs in the female gonads, the ovaries, within structures called follicles.

A. Site of Oogenesis:

- Ovaries: Female gonads where ova are produced and mature within follicles.

- Ovarian Follicles: Structures within the ovary that consist of an oocyte surrounded by one or more layers of support cells (granulosa cells). These cells nurture the developing oocyte and produce hormones (estrogens, progesterone).

B. Stages of Oogenesis:

Oogenesis involves phases of mitosis, meiosis, and growth, but with crucial differences in timing and cytoplasmic division compared to spermatogenesis.

1. Proliferation (Mitosis) - Occurs before birth

Oogonia (2n): Diploid (2n=46) stem cells in the fetal ovary. These multiply rapidly by mitosis during fetal development. By the fifth month of gestation, all oogonia that will ever develop are formed (up to 7 million). Many degenerate, but those remaining grow into primary oocytes. No new oogonia are formed after birth.

2. Meiosis - Highly Asynchronous

- Primary Oocyte (2n): A diploid cell that enters Meiosis I. Each primary oocyte becomes enclosed by a single layer of flattened follicular cells, forming a primordial follicle. Primary oocytes enter Prophase I of Meiosis during fetal development but then arrest at this stage. They remain arrested for years, even decades, until puberty.

- At Puberty: Starting at puberty, usually one primary oocyte per month is stimulated by hormones to resume meiosis. It completes Meiosis I to produce two unequal cells: a large secondary oocyte and a small first polar body. This unequal division (cytokinesis) ensures that the secondary oocyte retains most of the cytoplasm and nutrients. The first polar body may or may not divide again.

- Secondary Oocyte (n): This haploid (n=23, chromosomes with two chromatids) large cell enters Meiosis II. It then arrests at Metaphase II. The secondary oocyte is released from the ovary during ovulation.

- If fertilization occurs: The secondary oocyte completes Meiosis II to produce a large ovum (n=23, single chromatids) and a small second polar body.

- If fertilization does NOT occur: The secondary oocyte degenerates without completing Meiosis II.

- Ovum (n): The mature female gamete, fully haploid with single chromatids, ready for fusion with sperm.

Summary of Meiosis in Oogenesis:

- One primary oocyte (2n) yields one secondary oocyte (n) and one first polar body.

- One secondary oocyte (n) yields one ovum (n) and one second polar body only if fertilized.

- Therefore, one primary oocyte ultimately produces only one functional ovum and two or three non-functional polar bodies.

C. Timing of Oogenesis:

- Initiation: Begins in the fetal ovary.

- Arrested Development: Primary oocytes are arrested in Prophase I from fetal life until puberty. Secondary oocytes are arrested in Metaphase II until fertilization.

- Completion: Meiosis II is only completed upon successful fertilization.

- Discontinuous: Occurs in phases over many years.

5. Compare and Contrast Spermatogenesis and Oogenesis

Both spermatogenesis and oogenesis are processes of gametogenesis, involving meiosis to produce haploid gametes. However, they exhibit significant differences tailored to their distinct roles in reproduction.

A. Similarities:

- Involve Meiosis: Both processes utilize meiosis (Meiosis I and Meiosis II) to reduce the chromosome number from diploid (2n) to haploid (n), ensuring that the zygote formed upon fertilization has the correct diploid number of chromosomes.

- Produce Haploid Gametes: Both ultimately result in the formation of haploid cells (sperm and ovum) containing half the number of chromosomes of a somatic cell.

- Involve Mitosis: Both processes begin with the mitotic proliferation of primordial germ cells (spermatogonia and oogonia) to increase their numbers.

- Occur in Gonads: Both take place in the respective primary reproductive organs: testes for spermatogenesis and ovaries for oogenesis.

- Subject to Hormonal Control: Both processes are regulated by complex hormonal pathways involving the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis.

- Genetic Recombination: Both benefit from genetic recombination events (crossing over and independent assortment) during meiosis, contributing to genetic diversity.

B. Key Differences:

| Feature | Spermatogenesis | Oogenesis |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Testes (seminiferous tubules) | Ovaries (within follicles) |

| Timing | Starts at puberty, continuous throughout life | Starts during fetal development, discontinuous, ends at menopause |

| Duration of Process | Approximately 64-72 days (continuous cycle) | Many years (from fetal life to potential fertilization) |

| Number of Gametes from 1 Primary Cell | Four functional spermatozoa from one primary spermatocyte | One functional ovum and 2-3 polar bodies from one primary oocyte |

| Size of Gametes | Small, motile (spermatozoa) | Large, non-motile (ovum), rich in cytoplasm and nutrients |

| Cytokinesis | Equal division of cytoplasm during meiosis | Unequal division of cytoplasm during meiosis, forming polar bodies |

| Continuity | Continuous and prolific | Intermittent (typically one oocyte per month) and limited |

| Completion of Meiosis II | Completed before maturation | Completed only upon fertilization |

| Hormonal Control | LH stimulates Leydig cells (testosterone); FSH acts on Sertoli cells | LH and FSH stimulate follicular development, estrogen, and progesterone production; surge of LH triggers ovulation |

C. Evolutionary Significance of Differences:

The distinct strategies for gamete formation reflect evolutionary adaptations:

- Sperm Production: The male strategy is to produce vast numbers of small, motile gametes (sperm) to maximize the chances of reaching and fertilizing an egg. The continuous nature and equal cytoplasmic division support this high-volume production.

- Egg Production: The female strategy is to produce a limited number of large, nutrient-rich gametes (ova) that can support early embryonic development. The unequal cytoplasmic division ensures that the ovum receives all the necessary organelles and nutrients for the initial stages of a new organism. The long and arrested development stages allow for careful selection and maturation of a few high-quality ova.

This comparison highlights how both processes achieve the same fundamental goal (producing haploid gametes) but with profoundly different mechanisms, each optimized for its role in sexual reproduction.

Understand the Hormonal Regulation of Male Reproductive Function

Male reproductive function, including spermatogenesis and the development of male secondary sexual characteristics, is exquisitely controlled by a complex interplay of hormones, primarily orchestrated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis.

A. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) Axis (Male)

This axis involves three key endocrine glands that communicate with each other:

- 1 Hypothalamus: Located in the brain, master regulator.

- 2 Anterior Pituitary Gland: Base of brain, stimulated by hypothalamus.

- 3 Testes (Gonads): Primary reproductive organs.

B. Key Hormones and Their Roles

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH)

Source: Hypothalamus.

Action: Released in a pulsatile manner. Travels via portal system to anterior pituitary to stimulate release of gonadotropins.

Luteinizing Hormone (LH)

Source: Anterior Pituitary.

Action: Acts on Leydig cells (interstitial cells). Stimulates them to produce and secrete Testosterone.

Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH)

Source: Anterior Pituitary.

Action: Acts on Sertoli cells (sustentacular cells). Stimulates spermatogenesis (maturation) and production of Androgen-Binding Protein (ABP) to keep testosterone high in tubules.

Testosterone (Androgen)

Source: Leydig cells (stimulated by LH).

- Initiation/Maintenance of spermatogenesis.

- Male secondary sexual characteristics (muscle, voice, hair, libido).

- Maintenance of reproductive organs (prostate, etc.).

- Negative Feedback: Inhibits GnRH, LH, and FSH.

Inhibin

Source: Sertoli cells.

Action: Selectively inhibits FSH secretion from anterior pituitary. (Feedback for sperm production rate).

C. Negative Feedback Mechanisms

The HPG axis operates under a tight negative feedback loop:

Testosterone's Feedback

High levels inhibit GnRH (Hypothalamus) and LH/FSH (Pituitary). Prevents overproduction.

Inhibin's Feedback

High spermatogenesis → Inhibin release. Selectively inhibits FSH (Pituitary). Controls sperm count specifically.

D. Summary of Male Regulation

- Hypothalamus secretes GnRH.

- Pituitary releases LH & FSH.

- LH → Leydig cells → Testosterone.

- FSH → Sertoli cells → Spermatogenesis & Inhibin.

- Testosterone & Inhibin exert Negative Feedback.

Hormonal Regulation of Female Reproductive Cycles

Female function is also governed by the HPG axis but involves complex cycles (Ovarian & Uterine) to prepare for fertilization.

A. The HPG Axis (Female)

- Hypothalamus: Secretes GnRH.

- Anterior Pituitary: Secretes LH and FSH.

- Ovaries: Produce Estrogen/Progesterone, mature follicles, release oocyte.

B. Key Hormones and Their Roles

Estrogen (Estradiol)

Source: Developing follicles (Granulosa cells) & Corpus Luteum.

- Growth of endometrium (Proliferative phase).

- Secondary sexual characteristics.

- Feedback: Negative initially, but high levels switch to Positive Feedback (LH Surge).

Progesterone

Source: Corpus Luteum (after ovulation).

- Prepares endometrium (Secretory phase).

- Inhibits uterine contractions.

- Strong Negative Feedback on HPG axis.

- Raises basal body temperature.

C. The Ovarian Cycle (Avg. 28 days)

Events in the ovaries regarding oocyte maturation.

1. Follicular Phase Day 1-14

Hormones: FSH stimulates follicle growth. Dominant follicle produces rising Estrogen.

Feedback: Estrogen initially negative, then high levels switch to Positive Feedback.

2. Ovulation ~Day 14

Trigger: LH Surge (caused by high estrogen positive feedback). Mature follicle ruptures releasing oocyte.

3. Luteal Phase Day 14-28

Events: Corpus Luteum forms. Secretes high Progesterone (and estrogen).

Outcome: Strong negative feedback inhibits new follicles. If no pregnancy, CL degenerates → drop in hormones.

D. The Uterine (Menstrual) Cycle

Changes in the endometrium, correlated with ovarian events.

| Phase | Days | Key Events & Hormone Driver |

|---|---|---|

| Menstrual | 1-5 | Shedding of lining. Driver: Drop in Progesterone/Estrogen. |

| Proliferative | 6-14 | Rebuilding/Proliferation. Driver: Rising Estrogen (from follicles). |

| Secretory | 15-28 | Thickening/Secretion/Vascularization. Driver: Progesterone (from Corpus Luteum). |

E. Positive and Negative Feedback Loops

Negative Feedback (-)

Dominant for most of cycle. Estrogen/Progesterone inhibit GnRH/LH/FSH to prevent multiple ovulations.

Positive Feedback (+)

Critical Exception: High, sustained Estrogen switches to positive feedback → LH Surge → Ovulation.

Reproductive Cycles & Gametogenesis

Test your knowledge with these 30 questions.

Reproduction & Gametogenesis Quiz

Question 1/30

Quiz Complete!

Here are your results, .

Your Score

27/30

90%