Fertilization & Implantation: The Beginning of a New Individual

Fertilization

Fertilization, also known as conception, is the fundamental biological process where a male gamete (sperm) and a female gamete (secondary oocyte) fuse to form a new, single-celled entity called a zygote.

Fertilization is the process by which a male gamete (sperm) and a female gamete (ovum) fuse to form a new diploid cell called a zygote. This event typically occurs in the ampulla of the fallopian tube, usually within 12-24 hours after ovulation.

This remarkable union restores the diploid (2n) number of chromosomes and marks the very beginning of the development of a new, genetically unique individual.

Site of Fertilization

In humans, fertilization typically occurs in the ampulla of the fallopian tube (oviduct). This is the wider, outer portion of the tube, close to the ovary, where the egg is captured after ovulation.

The Key Players in Fertilization

Successful fertilization depends on the precise interaction of four critical components.

Sperm (Male Gamete)

A small, motile cell designed to travel through the female reproductive tract and deliver its haploid genetic material to the egg.

Egg (Secondary Oocyte)

A large, non-motile cell containing the female's haploid genetic material, cytoplasm, and all the necessary nutrients to support early embryonic development. It is arrested in Metaphase II of meiosis.

Zona Pellucida

A thick, glycoprotein-rich outer layer surrounding the egg. It acts as a species-specific binding site for sperm and is essential for preventing polyspermy (fertilization by more than one sperm).

Corona Radiata

The outermost layer of follicular (granulosa) cells that surrounds the zona pellucida, providing nourishment and protection to the ovulated egg.

The Journey of the Sperm

The passage of sperm through the female reproductive tract is a highly regulated and selective process, designed to ensure only sperm with normal morphology and vigorous motility reach the egg.

- Post-Ejaculation: Semen coagulates into a gel, protecting sperm from the vagina's acidic environment and holding them near the cervix. This gel liquefies within an hour.

- The Cervix: Cervical mucus acts as a barrier, filtering out sub-motile sperm.

- The Uterus: Uterine myometrial contractions, aided by prostaglandins in the seminal fluid, propel the sperm towards the fallopian tubes.

The first sperm enter the fallopian tubes minutes after ejaculation, but they can survive in the female reproductive tract for up to five days, awaiting ovulation.

The Events of Fertilization

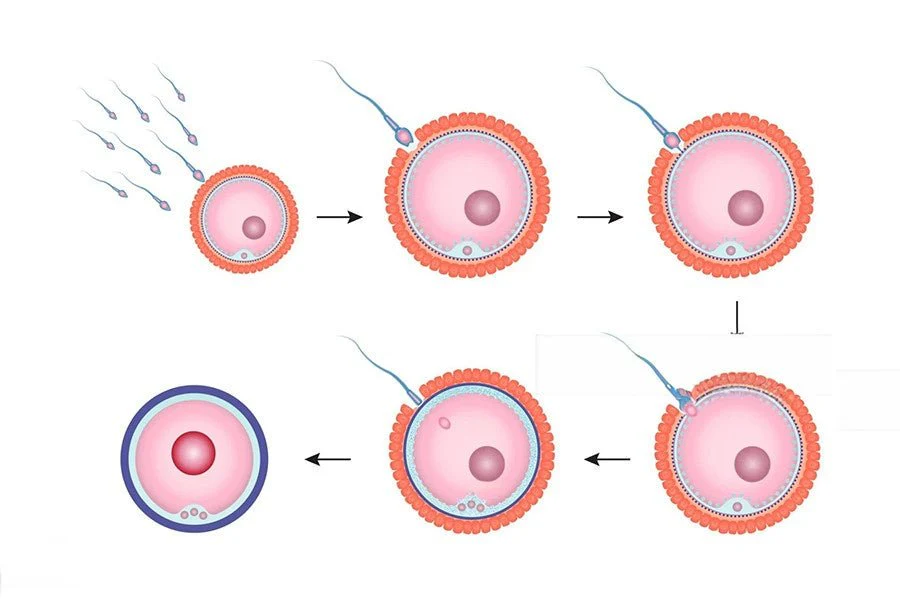

Once an ovulated egg is present, fertilization proceeds through a highly coordinated series of events.

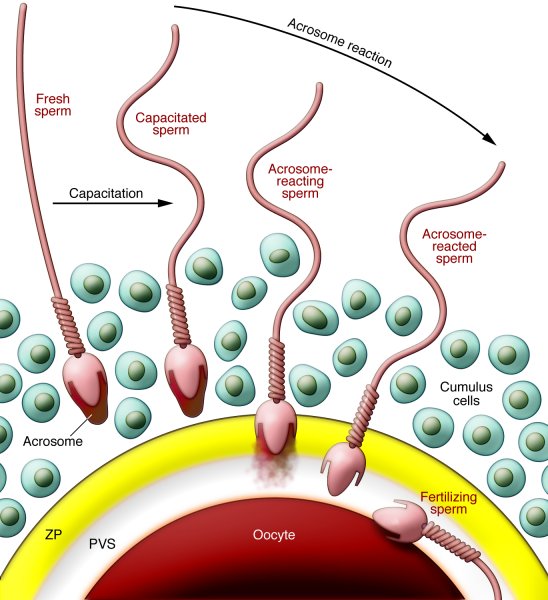

Event 1: Capacitation

A final maturation step that "arms" the sperm within the female reproductive tract.

The Process: The female tract's environment strips away cholesterol and proteins from the sperm's head.

The Result: The sperm's tail becomes hyper-motile, and its acrosome membrane is destabilized, ready to release enzymes.

Key takeaway: A sperm cannot fertilize an egg until it has been capacitated.

A. Sperm Transport and Capacitation

1. The Journey

- Ejaculation & Vaginal Transit: Millions of sperm deposited in posterior fornix. Many lost to acidity/leukocytes.

- Cervical & Uterine Passage: Sperm navigate the cervix (mucus becomes permeable) and uterine cavity.

- Fallopian Tube: Only a few thousand reach the tubes, guided by chemotaxis and uterine contractions.

2. Capacitation (Maturation)

Crucial process (2-10 hours) in female tract involving:

- Membrane Changes: Removal of cholesterol/glycoproteins from sperm head (acrosomal region). Increases fluidity/reactivity.

- Hyperactivation: Increased flagellar beating (vigorous/erratic) essential for penetrating egg layers.

Result: Sperm is now capable of the acrosomal reaction.

Event 2: The Acrosomal Reaction

Penetrating the Corona Radiata: Hyper-motile sperm push through the outer layer of follicular cells.

Binding to the Zona Pellucida: The sperm binds to species-specific ZP3 receptors on the zona pellucida, like a key in a lock.

Releasing Enzymes: This binding triggers the acrosome to release digestive enzymes (like acrosin).

Digesting a Path: These enzymes create a tunnel through the zona pellucida, allowing the sperm to reach the egg's cell membrane.

B. Penetration of the Egg's Protective Layers

Upon reaching the secondary oocyte, capacitated sperm must penetrate two barriers:

1. Corona Radiata Penetration

Sperm use hyperactivated motility to push through. Enzymes like hyaluronidase (on sperm surface) break down hyaluronic acid in the extracellular matrix.

2. Zona Pellucida Penetration

- Binding: Sperm proteins bind to specific receptors (primarily ZP3 glycoprotein) on the Zona Pellucida. (Species-specific).

- Acrosomal Reaction: Binding to ZP3 triggers fusion of acrosomal membrane with sperm plasma membrane. Releases hydrolytic enzymes (acrosin, neuraminidase).

- Digestion & Motility: Enzymes digest a path; sperm tail thrusts push sperm through.

C. Fusion of Sperm and Oocyte Membranes

- Sperm reaches the perivitelline space.

- Sperm head lies flat against oocyte plasma membrane.

- Membranes fuse.

- Sperm head, tail, mitochondria, and centriole enter oocyte cytoplasm.

Events 3 & 4: The Blocks to Polyspermy

To prevent a lethal condition where more than one sperm fertilizes the egg, the oocyte deploys a two-stage defense system.

Fast Block (Immediate but Temporary)

The instant fusion of the first sperm triggers a rapid influx of sodium ions (Na⁺) into the oocyte, instantly changing the membrane's electrical charge to repel all other sperm.

Slow Block (Cortical Reaction - Permanent)

Sperm fusion also triggers a massive release of calcium ions (Ca²⁺) inside the oocyte. This causes cortical granules to release enzymes that destroy all ZP3 receptors and harden the zona pellucida, making it impenetrable.

D. Prevention of Polyspermy (Block to Polyspermy)

Mechanisms to ensure only ONE sperm fertilizes the egg (preventing lethal abnormal chromosome numbers).

1. Fast Block (Electrical)

Rapid, transient depolarization of oocyte membrane prevents other sperm fusion. (Less prominent in humans).

2. Slow Block (Cortical)

Primary Mechanism. Sperm fusion triggers intracellular Ca2+ surge.

Cortical Reaction: Cortical granules release enzymes into perivitelline space causing:

- Zona Reaction: Hardens Zona Pellucida (cleaves ZP2, inactivates ZP3).

- Release of loosely attached sperm.

E. Completion of Meiosis II

The Ca2+ surge stimulates the secondary oocyte to finish division.

- Forms Mature Ovum (Female Pronucleus).

- Releases Second Polar Body.

- Male and Female Pronuclei swell and replicate DNA.

F. Syngamy & Zygote Formation

Pronuclear membranes break down. Chromosomes intermingle.

- Syngamy: Fusion of genetic material.

- Formation of diploid Zygote (46 chromosomes).

- Zygote immediately begins first mitotic division.

The Fusion and Formation of the Zygote

Oocyte Completes Meiosis: The calcium wave also signals the secondary oocyte to complete Meiosis II, forming the mature ovum and a second polar body.

Fusion of Pronuclei (Syngamy): The male pronucleus (from the sperm) and the female pronucleus (from the ovum) swell and then fuse their genetic material.

The Result: A zygote is formed—a new, single cell with the restored diploid number of 46 chromosomes, containing genetic material from both parents.

Summary

The formation of the zygote is the remarkable start of a new individual. This single cell holds all the genetic instructions for development. From this point, the journey of rapid cell division and differentiation begins, as the zygote makes its way towards the uterus.

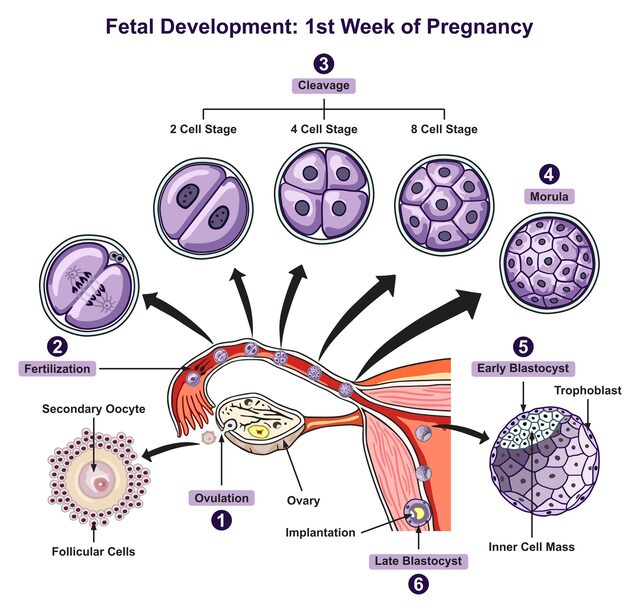

Cleavage, Morula, and Blastocyst Formation

Immediately following fertilization, the zygote undergoes a series of rapid mitotic divisions known as cleavage, without significant growth of the embryo as a whole. This process transforms the single-celled zygote into a multicellular structure while it simultaneously travels down the fallopian tube towards the uterus.

Cleavage is the initial series of rapid mitotic cell divisions that a newly formed zygote undergoes immediately after fertilization. This process transforms the single-celled zygote into a multicellular structure ready for implantation.

Key Characteristics of Cleavage

A. Cleavage (Day 1-4 Post-Fertilization)

Definition & Characteristics

- Rapid Mitosis: A series of divisions where cells (called blastomeres) become progressively smaller.

- No Growth: These divisions occur without an increase in the overall size of the embryonic mass.

- Timing/Location: Begins approx. 24 hours post-fertilization in the fallopian tube.

- Purpose: To increase cell number exponentially for differentiation and prepare for blastocyst formation.

Stages of Cleavage

Approx. 24 hours post-fertilization. First mitotic division completes.

Divisions continue.

Blastomeres maximize contact forming a compact ball.

A Timeline

B. Morula Formation (Day 4 Post-Fertilization)

As the morula continues to divide, a fluid-filled cavity (the blastocoel) forms inside, transforming the solid ball into a more complex structure called the blastocyst. The cells reorganize into two distinct, crucial groups: Inner cell mass(Embryoblast) and Trophoblast

The Morula ("Mulberry")

- Structure: A solid ball of 16-32 tightly packed, indistinguishable blastomeres.

- Location: Within fallopian tube or entering uterine cavity.

- Potency: Cells are Totipotent (each cell has potential to develop into a complete organism).

C. Blastocyst Formation (Day 5-6 Post-Fertilization)

As uterine fluid penetrates the zona pellucida, it accumulates within the morula, forming a central cavity called the blastocoel. This transforms the morula into a blastocyst.

Differentiation within the Blastocyst

The cells are no longer totipotent but have differentiated into two populations:

Inner Cell Mass (ICM) / Embryoblast

- Cluster of cells located eccentrically at one pole.

- Pluripotent: Can give rise to the embryo proper (fetus) and some extraembryonic membranes (yolk sac, amnion).

- Source of embryonic stem cells.

Trophoblast

- Thin, outer layer of flattened cells forming the wall.

- Crucial for implantation and formation of the placenta (chorion).

- Does NOT contribute to the embryo proper.

Around day 5-6, the blastocyst "hatches" from the zona pellucida, ready for implantation.

Hatching (Day 5-6)

Before implantation, the blastocyst must "hatch" from the zona pellucida. Enzymes released by the trophoblast, along with blastocyst contractions, break the zona pellucida. This is essential because the zona pellucida would otherwise prevent the trophoblast from contacting the uterine endometrium.

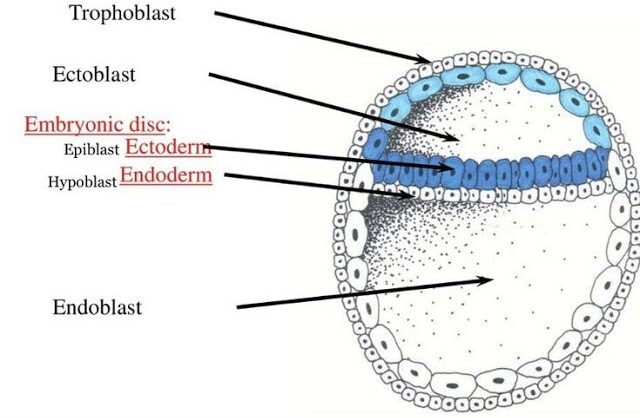

Formation of the Bilaminar Disc

Just as implantation begins, the Inner Cell Mass (ICM) differentiates into two critical layers, forming the bilaminar (two-layered) embryonic disc.

Epiblast (Upper Layer)

Faces the trophoblast. Crucially, all three primary germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm) arise from the epiblast. The entire fetus develops from this layer.

Hypoblast (Lower Layer)

Faces the blastocoel. Contributes to extraembryonic structures, primarily the yolk sac, and provides important signaling to the epiblast.

Purpose of Cleavage

- Increase Cell Number: To generate enough cells for future development.

- Prepare for Implantation: To form the trophoblast, which is essential for implanting in the uterus.

- Establish Basic Organization: To create the initial distinction between cells that will form the embryo (ICM) and cells that will form the placenta (trophoblast).

Summary

This journey from a single zygote to a free-floating blastocyst within the uterine cavity is a remarkable feat of rapid cell division and initial differentiation. The stage is now set for the next critical event: the physical attachment of the blastocyst to the uterine wall.

Implantation

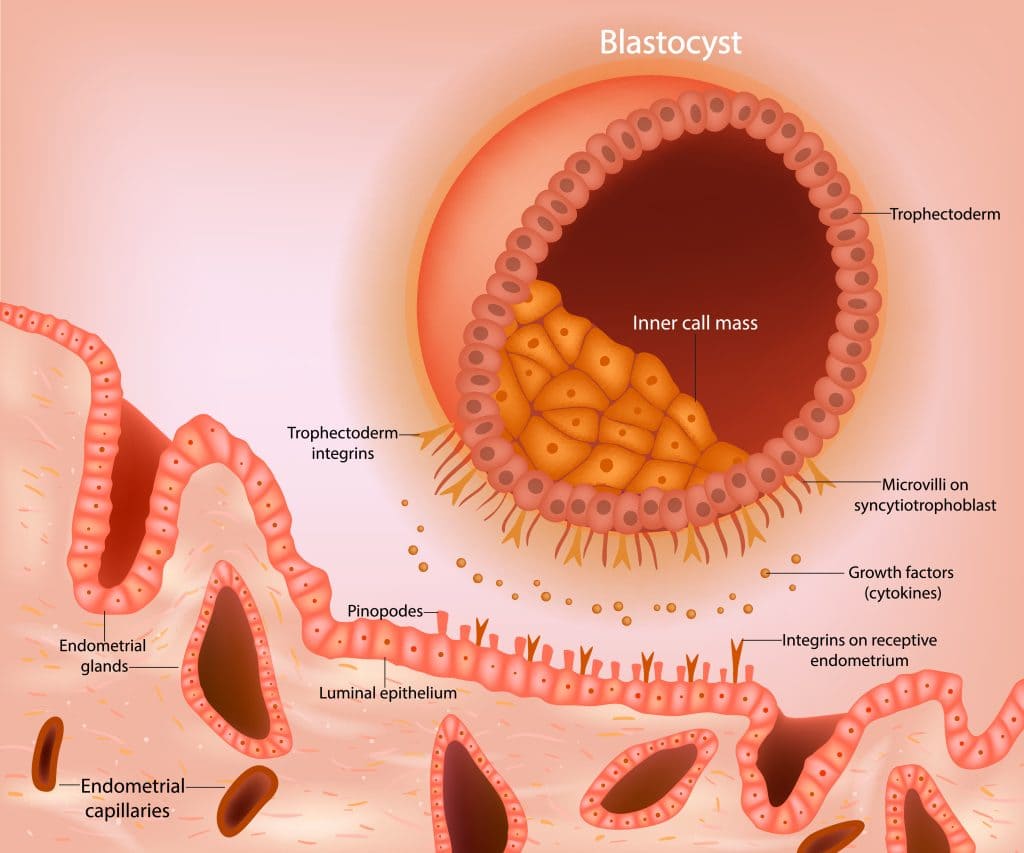

Implantation is the process by which the hatched blastocyst adheres to and subsequently invades the uterine endometrium, embedding itself within the maternal tissue. This event is absolutely essential for the successful establishment of pregnancy and typically occurs around Day 6-12 post-fertilization.

The uterine endometrium, under the influence of progesterone, must be in a receptive state ("window of implantation"), usually lasting from day 20 to 24 of a typical cycle.

Implantation is the crucial process by which the early embryo, now at the blastocyst stage, attaches itself to and invades the inner lining of the uterus, the endometrium. This typically occurs around 6 to 12 days after fertilization.

Prerequisites for Successful Implantation

For implantation to occur, two main conditions must be perfectly met, creating a synchronized "dialogue" between the embryo and the uterus.

1. A Competent Blastocyst

The blastocyst must be well-developed and, most importantly, must have "hatched" from its protective zona pellucida. This hatching allows the trophoblast cells to make direct contact with the uterine lining.

2. A Receptive Endometrium

The uterine lining must be in its secretory phase, made thick and nutrient-rich by the hormone progesterone. This period of optimal readiness is known as the "implantation window."

The Three Stages of Implantation

1. Apposition (Initial Contact / Orientation)

What it is: This is the very first, often loose, physical contact between the hatched blastocyst and the endometrial surface. It is essentially about the blastocyst "finding its spot."

Location: Most commonly, the blastocyst positions itself with its embryonic pole (the end containing the Inner Cell Mass, or ICM) facing the endometrial epithelium. This orientation is crucial for directed invasion and proper development.

Cellular Mechanisms of Apposition

-

Endometrial Receptivity:

The uterine endometrium must be in a specific "receptive window" (usually days 20-24 of a 28-day menstrual cycle) for implantation to succeed. This receptivity is hormonally controlled, primarily by progesterone.

-

Pinopodes:

During this receptive phase, the endometrial epithelial cells develop transient, finger-like protrusions called pinopodes. These structures are thought to facilitate fluid absorption, bringing the blastocyst closer to the epithelial surface, and may also be involved in cellular recognition and adhesion.

-

Glycocalyx Interactions:

Initial, weak interactions occur between the specialized carbohydrate-rich coat (glycocalyx) of the trophoblast cells and the glycocalyx of the endometrial epithelial cells.

-

Electrostatic Forces:

Subtle electrostatic forces may also play a role in this initial loose contact.

2. Adhesion (Firm Attachment)

What it is: Following apposition, the blastocyst establishes a more stable and firm attachment to the endometrial epithelial cells. This is no longer just a loose contact; it is a commitment to bind.

Cellular Mechanisms: This stage is characterized by a sophisticated molecular dialogue between the trophoblast and the endometrium, involving various adhesion molecules.

Integrins

These are transmembrane receptors found on both trophoblast and endometrial cells. They act as bridges, binding to extracellular matrix components (like fibronectin, laminin, collagen) and linking them to the cell's cytoskeleton.

αvβ3 and α4β1 are upregulated on the endometrial surface during the receptive window.

Selectins

Carbohydrate-binding proteins involved in initial transient adhesion. L-selectin on the trophoblast is thought to bind to carbohydrate ligands on the endometrial surface, facilitating initial rolling and weak attachment.

Cadherins

Calcium-dependent cell adhesion molecules important for cell-to-cell binding. E-cadherin, for instance, is expressed in the endometrium and may play a role in trophoblast-endometrial interactions.

Growth Factors & Cytokines

Local factors secreted by the endometrium modulate adhesion molecule expression.

LIF (Leukocyte Inhibitory Factor) is particularly highlighted as crucial for enhancing endometrial receptivity and trophoblast adhesiveness.

3. Invasion (Penetration into the Endometrium)

What it is: This is the most active and transformative stage, where the blastocyst breaks down the endometrial lining and burrows deep into the uterine stroma. This process is highly regulated to prevent excessive invasion.

A. Trophoblast Differentiation

Upon contact with the endometrium, the trophoblast cells at the embryonic pole undergo rapid proliferation and differentiation into two distinct layers:

Cytotrophoblast (CTB)

The Inner Layer

This is the inner layer of mononucleated, mitotically active cells. These are the progenitor cells that continuously divide and fuse to form the outer layer. They form a distinct cellular layer.

Syncytiotrophoblast (STB)

The Outer, Invasive Layer

This is the outer layer, a highly invasive, multinucleated mass of cytoplasm formed by the fusion of underlying cytotrophoblast cells. Crucially, the STB has no distinct cell boundaries.

B. Mechanisms of Invasion

The syncytiotrophoblast is the primary invasive component. It secretes a battery of proteolytic enzymes:

- Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs): These enzymes (e.g.,

MMP-2,MMP-9) degrade the components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the endometrium, such as collagen, laminin, and fibronectin. This breakdown allows the blastocyst to literally digest its way into the uterine wall. - Serine Proteinases: Other proteinases also contribute to the degradation of the ECM.

The syncytiotrophoblast actively engulfs and phagocytoses apoptotic endometrial cells and cellular debris, clearing a path for the invading embryo.

- Angiogenesis: The invading trophoblast secretes factors that promote the growth of new blood vessels within the endometrium, essential for establishing the uteroplacental circulation.

- hCG Secretion: The STB produces human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) almost immediately. This maintains the corpus luteum → progesterone → prevents menstruation.

Closing Plug Formation: As the blastocyst burrows deeper, the endometrial epithelial defect (the entry point) is eventually closed by a coagulation plug of fibrin and cellular debris, sealing off the implantation site.

Summary of Invasion Progress

D. Hormonal Support of Implantation

Progesterone

Critical for preparing endometrium (secretory phase) and maintaining pregnancy. Initially secreted by Corpus Luteum.

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG)

- Produced by Syncytiotrophoblast as soon as implantation begins.

- Structurally similar to LH.

- Function: "Rescues" the Corpus Luteum, maintaining Progesterone production (preventing menstruation).

- Clinical: Detected by home pregnancy tests.

Summary

With successful implantation, the embryo is securely anchored within the maternal uterus, establishing a direct connection for nutrient exchange and hormonal support. This marks the end of the pre-embryonic period and the beginning of embryonic development.

Initial Placenta Formation

As we discussed with invasion, the blastocyst's engagement with the endometrium immediately kickstarts the development of the earliest placental structures. The placenta is a vital organ that facilitates nutrient, gas, and waste exchange between the mother and the developing embryo/fetus, and it also produces crucial hormones.

The foundation of the placenta is laid during the implantation process, primarily through the differentiation and expansion of the trophoblast.

Recall from Implantation (Day 6/7 onwards):

The trophoblast layer of the blastocyst, upon contact with the endometrium, differentiates into two key layers:

- Cytotrophoblast (CTB): The inner, cellular layer.

- Syncytiotrophoblast (STB): The outer, invasive, multinucleated layer.

A. Development and Roles of the Cytotrophoblast and Syncytiotrophoblast in Placental Formation

1. Syncytiotrophoblast (STB): The Invasive Frontier & Exchange Mediator

Formation: Formed by the continuous fusion of underlying cytotrophoblast cells. This process is ongoing throughout placental development, especially in the early stages.

Key Characteristics:- Multinucleated: Contains numerous nuclei within a single, continuous cytoplasm. This means there are no individual cell membranes separating nuclei.

- Non-mitotic: Once a cytotrophoblast cell fuses to become part of the syncytiotrophoblast, it loses its ability to divide. The STB grows by accreting new CTB cells.

- Highly Invasive: As detailed previously, the STB is the primary agent of invasion during implantation. It secretes proteolytic enzymes (

MMPs) to break down the endometrial extracellular matrix, allowing the blastocyst to embed.

Roles in Placenta Formation & Function:

As the STB invades, it erodes the walls of maternal spiral arteries and venous sinusoids within the endometrium.

Lacunae Formation: Small, fluid-filled spaces (lacunae) develop within the expanding STB mass.

Lacunar Network: These lacunae rapidly coalesce to form an interconnected network.

Maternal Blood Inflow: As maternal capillaries are eroded, blood flows into these lacunar spaces, directly bathing the syncytiotrophoblast. This marks the establishment of the rudimentary uteroplacental circulation. This is the first critical step in enabling maternal-fetal exchange.

The STB is the direct interface with maternal blood. It is responsible for:

- Active Transport: Facilitating the uptake of nutrients (glucose, amino acids, vitamins) from maternal blood and transporting them to the embryo.

- Passive Diffusion: Allowing for the diffusion of gases (oxygen to embryo, carbon dioxide from embryo) and other small molecules.

- Waste Product Transfer: Facilitating the transfer of embryonic waste products (e.g., urea) into maternal circulation for excretion.

The STB is a major endocrine organ of pregnancy. It synthesizes and secretes critical hormones:

Crucial for maintaining the corpus luteum and progesterone production in early pregnancy. This prevents menstruation.

Takes over from the corpus luteum around 7-10 weeks of gestation as the primary source of progesterone, which is essential for maintaining uterine quiescence and pregnancy.

Produced by the placenta in increasing amounts throughout pregnancy, contributing to uterine growth and mammary gland development.

Involved in maternal metabolism and fetal growth.

Immunomodulation: The STB plays a role in protecting the semi-allogeneic embryo from maternal immune rejection.

2. Cytotrophoblast (CTB): The Progenitor Layer & Structural Contributor

Formation: Derived from the trophoblast cells of the blastocyst.

Key Characteristics:- Mononucleated: Composed of individual cells, each with a single nucleus.

- Mitotically Active: These cells continuously divide, providing a fresh supply of cells.

- Inner Layer: Forms a distinct cellular layer internal to the syncytiotrophoblast.

Roles in Placenta Formation & Function:

The primary role of the CTB is to serve as the progenitor cell population for the syncytiotrophoblast. CTB cells proliferate and then differentiate by fusing with the existing STB layer. This continuous renewal is vital for the growth and function of the STB.

- As the lacunar network within the STB expands and fills with maternal blood, the cytotrophoblast cells begin to proliferate and form finger-like projections.

- These solid cords of cytotrophoblast cells grow into the blood-filled lacunae, forming the primary chorionic villi. These villi are essentially columns of cytotrophoblast cells surrounded by syncytiotrophoblast.

- The formation of these villi significantly increases the surface area for exchange between maternal blood and embryonic tissues, laying the groundwork for a more efficient placenta.

In later development, some cytotrophoblast cells differentiate and invade the maternal decidua (the modified endometrium) to form extravillous cytotrophoblast (EVCT). These cells remodel maternal spiral arteries, ensuring adequate blood supply to the intervillous space and anchoring the placenta to the uterine wall. (While this happens a bit later, the CTB is the origin of these crucial cells).

Summary of Initial Placental Events (Day 9-12)

hCG.

The interplay between the cytotrophoblast (proliferating and forming the structural backbone) and the syncytiotrophoblast (invading, facilitating exchange, and secreting hormones) is fundamental to the successful establishment of the placenta. This early phase is characterized by rapid growth and integration into the maternal uterine wall, setting the stage for the more complex villous tree development.

Fertilization & Implantation

Test your knowledge with these 29 questions.

Fertilization & Implantation Quiz

Question 1/29

Quiz Complete!

Here are your results, .

Your Score

26/29

90%