Digestion, Absorption & GIT Disorders

Digestion, Absorption & GIT Disorders

Digestion is the process of breaking down complex food molecules into simpler forms that can be absorbed by the body. Absorption is the subsequent process of transporting these digested nutrients from the lumen of the GI tract into the bloodstream or lymphatic system.

I. Why Digestion?

The human body relies on three main macronutrients: 1. Carbohydrates, 2. Fats, 3. Proteins.

Additionally, small quantities of vitamins and minerals are essential. These macronutrients, in their natural, complex forms (e.g., starch, triglycerides, large proteins), cannot be directly absorbed through the gastrointestinal (GIT) mucosa. They are "useless as nutrients without preliminary digestion."

Digestion by Hydrolysis

Digestion primarily occurs through hydrolysis, a chemical process where water molecules are added to break down larger molecules into smaller ones. This process reverses the condensation reactions that originally formed these macromolecules.

Carbohydrates

- Exist mostly as large polysaccharides (e.g., starch) or disaccharides (e.g., sucrose, lactose).

- Formed by condensation (removal of a water molecule between monosaccharide units).

- Hydrolysis, catalyzed by specific enzymes, reverses this, yielding monosaccharides.

Fats

- Exist as triglycerides (one glycerol molecule attached to three fatty acid molecules).

- Formed by condensation, with three water molecules removed.

- Hydrolysis, by fat-digesting enzymes, reverses this, forming fatty acids and glycerol.

Proteins

- Formed from multiple amino acids linked by peptide bonds (a condensation reaction).

- Proteolytic enzymes (proteases) reverse this, breaking peptide bonds to yield smaller peptides and ultimately amino acids.

II. Digestion of Specific Macronutrients

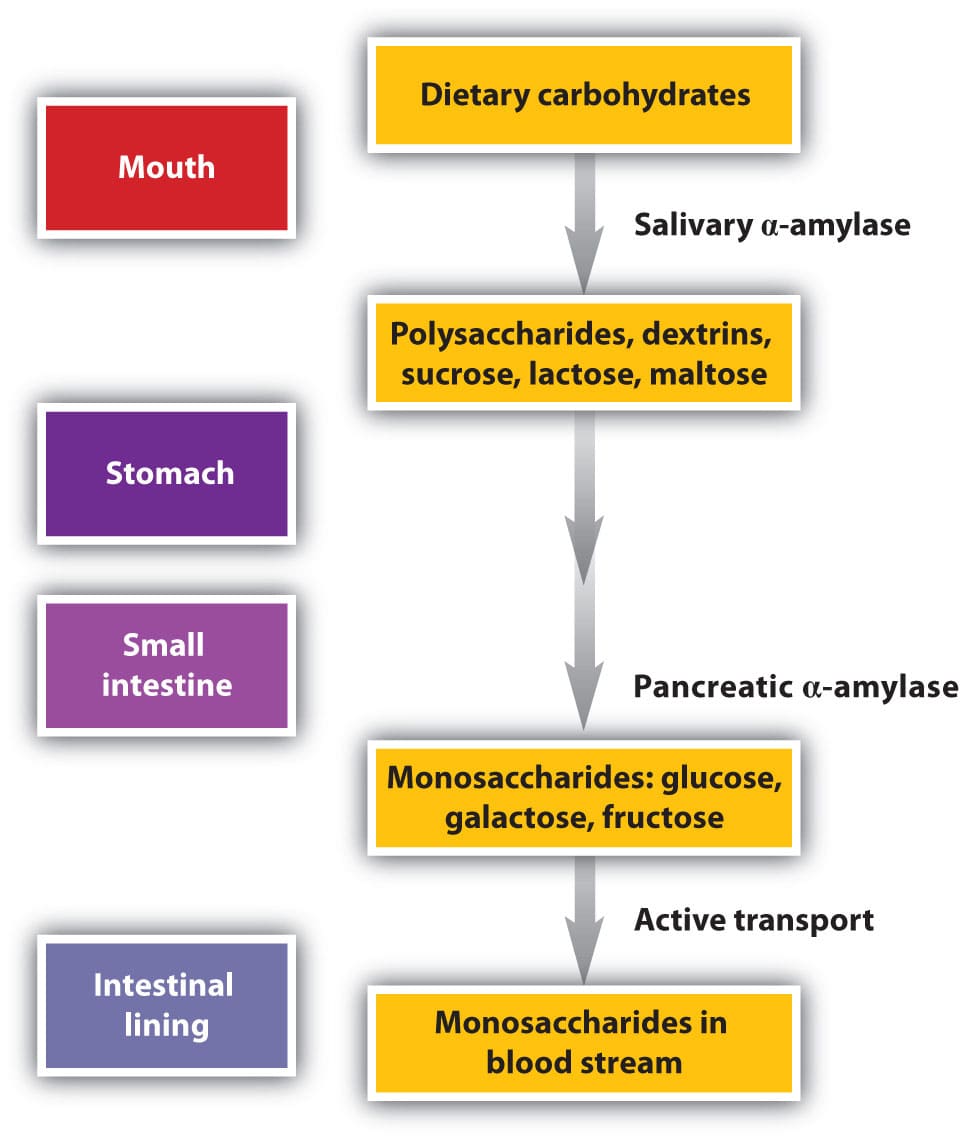

A. Digestion of Carbohydrates

- Major Dietary Sources:

- Sucrose: Disaccharide, commonly known as cane sugar.

- Lactose: Disaccharide, found in milk.

- Starches: Large polysaccharides, present in almost all non-animal foods (e.g., potatoes, grains).

- Other Minor Sources: Amylose, glycogen, alcohol, lactic acid, pyruvic acid, pectins, dextrins, and minor carbohydrate derivatives in meats.

- Cellulose: Not digestible by humans as we lack the necessary enzymes.

Locations of Digestion:

- Mouth: Salivary amylase (ptyalin) initiates starch digestion, breaking it into smaller polysaccharides (dextrins) and some maltose. Accounts for about 5% of carbohydrate digestion.

- Stomach: Salivary amylase continues to act in the fundus and body of the stomach until it is inactivated by the acidic gastric juice. Can digest 30-40% of starches into dextrins and maltose.

- Small Intestine (Final Stage): This is where the bulk of carbohydrate digestion occurs.

- Pancreatic Amylase: Secreted by the pancreas into the duodenum, it breaks down starches and dextrins into maltose and other small glucose polymers.

- Brush Border Enzymes: Located on the microvilli of enterocytes (intestinal epithelial cells). These enzymes are responsible for the final breakdown of disaccharides into monosaccharides:

- Lactase: Digests lactose into glucose and galactose.

- Sucrase: Digests sucrose into glucose and fructose.

- Maltase: Digests maltose and other small glucose polymers into glucose.

Final Products: The final products of carbohydrate digestion are exclusively monosaccharides (glucose, galactose, fructose), which are the only forms absorbable into the bloodstream.

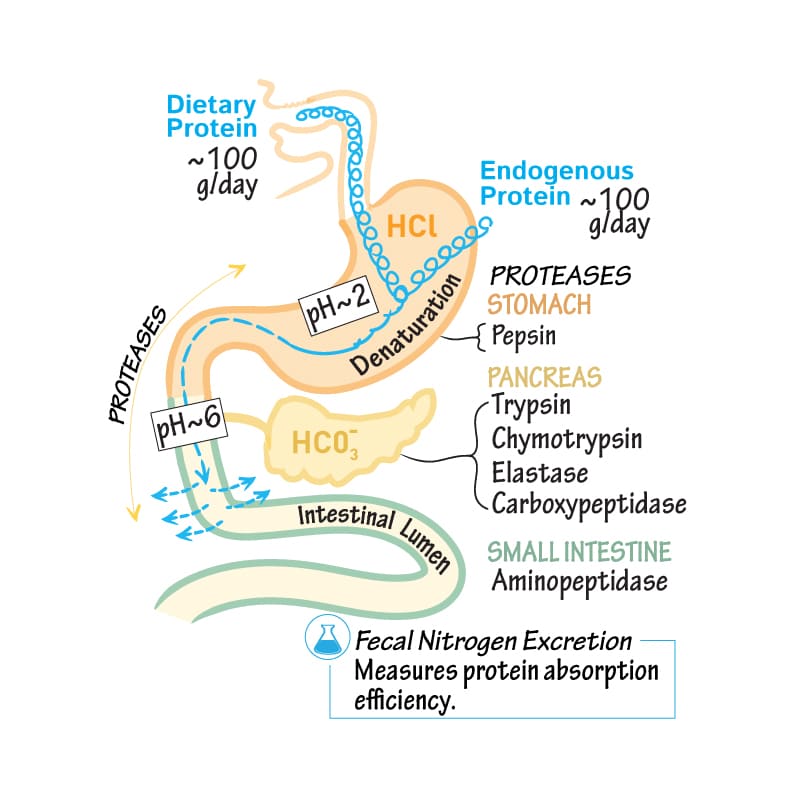

B. Digestion of Proteins

Locations of Digestion:

- Stomach:

- Pepsin: Secreted by chief cells as pepsinogen and activated by hydrochloric acid (HCl) at a pH of 2-3.

- Pepsin initiates protein digestion, breaking down proteins into proteoses, peptones, and large polypeptides. Accounts for 10-20% of total protein digestion.

- Small Intestine:

- Pancreatic Secretions: The majority of protein digestion occurs in the upper small intestine (duodenum and jejunum) due to powerful pancreatic proteolytic enzymes.

- Trypsin, Chymotrypsin, Carboxypolypeptidase, Proelastase: These enzymes (secreted as inactive zymogens and activated in the duodenum) break down proteins, proteoses, peptones, and large polypeptides into smaller polypeptides, tripeptides, dipeptides, and a few free amino acids.

- Brush Border Peptidases (in Enterocytes): Located on the luminal surface of enterocytes lining the intestinal villi (especially in the duodenum and jejunum).

- Aminopolypeptidase and Dipeptidases: These enzymes further digest the small polypeptides, tripeptides, and dipeptides into their final absorbable form: amino acids.

- Pancreatic Secretions: The majority of protein digestion occurs in the upper small intestine (duodenum and jejunum) due to powerful pancreatic proteolytic enzymes.

End Products of Luminal Digestion: Dipeptides, tripeptides, and amino acids.

Final Absorbable Form: Over 99% of the final protein products are absorbed as amino acids.

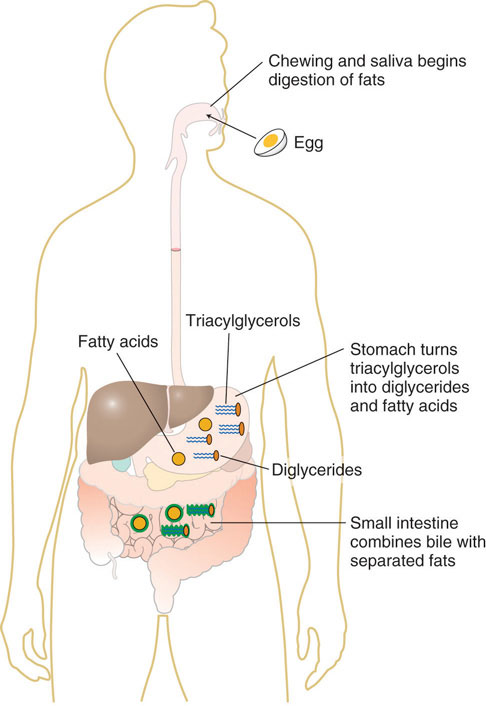

C. Digestion of Fats

- Primary Location: Almost entirely occurs in the small intestine.

- Two Main Steps:

- Emulsification: Large fat globules are broken down into smaller droplets.

- Bile Acids and Lecithin: These components of bile, secreted by the liver, are amphipathic molecules that surround fat droplets, reducing their surface tension and preventing them from coalescing.

- This process increases the surface area of fat by approximately 1000-fold, making it accessible to water-soluble digestive enzymes.

- Enzymatic Action:

- Pancreatic Lipase: The most important enzyme for fat digestion, secreted by the pancreas. It hydrolyzes triglycerides into monoglycerides and free fatty acids.

- Enteric Lipase: Also present in the small intestine, contributing to fat digestion.

- Cholesterol Ester Hydrolase: Hydrolyzes cholesterol esters into cholesterol and fatty acids.

- Phospholipase A2: Hydrolyzes phospholipids (like lecithin) into lysophospholipids and fatty acids.

- Emulsification: Large fat globules are broken down into smaller droplets.

- Final Products: Monoglycerides, free fatty acids, cholesterol, and lysophospholipids.

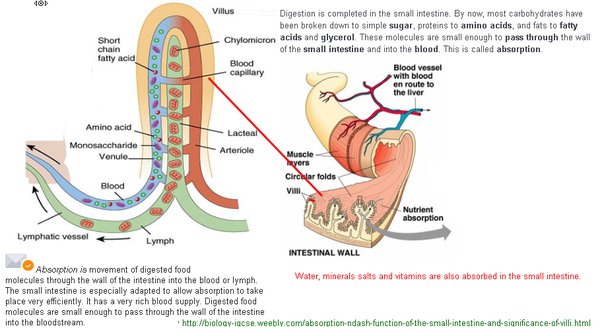

III. Absorption of Digested Food

Absorption is the process by which digested food materials move from the lumen of the GIT into the blood or lymph.

- Mechanisms: Involves both passive processes (e.g., diffusion, osmosis) and active processes (e.g., active transport, co-transport).

- Fluid Balance:

- Total fluid ingested per day: ~1.5 liters.

- Total fluid secreted into GIT (saliva, gastric juice, bile, pancreatic juice, intestinal secretions): ~7 liters.

- Total fluid entering small intestine: ~8.5 liters.

- Total fluid absorbed per day: ~8-9 liters.

- Most absorption (all but ~1.5 liters) occurs in the small intestine.

- Only about 1.5 liters pass through the ileocecal valve into the colon each day.

A. Absorptive Surface of the Small Intestine

The small intestine has an enormous surface area, crucial for efficient absorption. This is achieved through multiple levels of folding:

- Valvulae Conniventes (Folds of Kerckring): Large circular folds of the mucosa and submucosa, particularly well-developed in the duodenum and jejunum (up to 8mm high), increasing surface area by ~3-fold.

- Villi: Millions of small, finger-like projections (0.5-1mm long) covering the entire surface of the small intestine. Each villus is covered by epithelial cells and contains a lacteal (lymphatic capillary) and a rich capillary network. Villi increase surface area by ~10-fold.

- Microvilli (Brush Border): Each epithelial cell covering the villi has thousands of microscopic, hair-like projections called microvilli on its apical surface. This "brush border" increases surface area by ~20-fold.

- Combined Effect: This hierarchical arrangement of folds, villi, and microvilli collectively increases the effective absorptive surface area of the small intestine by hundreds of times, making it incredibly efficient.

B. Daily Absorption in Small Intestine

The small intestine is capable of absorbing large quantities of nutrients and water:

- Carbohydrates: Several hundred grams (up to kilograms).

- Fat: 100g or more (up to 500g).

- Amino acids: 50-100g (up to 500-700g of proteins).

- Ions: 50-100g.

- Water: 7-8 liters (up to >20 liters).

C. Absorption Mechanisms

1. Absorption of Water

- Occurs primarily by osmosis (diffusion).

- Isosmotic Absorption: Water is absorbed passively in response to osmotic gradients created by the active transport of solutes (especially Na+).

- When chyme is dilute (hypotonic), water moves from the lumen into the blood in the villi.

- Conversely, if hyperosmotic solutions are discharged from the stomach into the duodenum, water will initially move into the lumen, diluting the chyme, before being reabsorbed.

2. Absorption of Ions (Na+, Cl-, Bicarbonate, Ca++, Iron, K+, Mg++, Phosphate)

- Sodium (Na+): Actively absorbed from the intestinal lumen into the epithelial cells, and then actively pumped out of the cells into the interstitial fluid.

- This active transport of Na+ creates an electrical gradient, driving Cl- absorption.

- It also creates an osmotic gradient, causing water to follow Na+ (isosmotic absorption).

- Chloride (Cl-): Follows Na+ passively due to the electrical gradient.

- Bicarbonate (HCO3-): Actively absorbed, often by exchanging with Cl-. It is transported into the cells and then often converted to CO2, which diffuses into the blood.

- Calcium (Ca++): Actively absorbed, a process regulated by parathyroid hormone (PTH) and Vitamin D.

- Iron (Fe++): Also actively absorbed, with its uptake carefully regulated based on the body's needs.

- Potassium (K+), Magnesium (Mg++), Phosphate (PO4---): Can also be actively absorbed.

- Note on Valency: Monovalent ions (e.g., Na+, K+, Cl-) are absorbed with ease and in large quantities. Bivalent ions (e.g., Ca++, Mg++, Fe++) are absorbed in smaller amounts (e.g., maximal Ca++ absorption is only 1/50th that of Na+).

3. Absorption of Carbohydrates

- Mainly absorbed as monosaccharides (glucose, galactose, fructose).

- Very little as disaccharides, almost none as larger carbohydrate compounds.

- Distribution: Approximately 80% as glucose, 20% as galactose and fructose.

- Mechanism: Virtually all monosaccharides are absorbed by active transport processes.

- Glucose and Galactose: Co-transported with Na+ via the SGLT1 transporter (Sodium-Glucose Linked Transporter 1) on the brush border membrane. The energy for this comes indirectly from the active pumping of Na+ out of the cell by the Na+/K+ ATPase on the basolateral membrane, creating a low intracellular Na+ concentration.

- Fructose: Absorbed by facilitated diffusion via the GLUT5 transporter on the brush border membrane. Once inside the cell, a portion of fructose is phosphorylated and converted to glucose. Fructose exits the cell into the blood via GLUT2.

4. Absorption of Proteins

- Absorbed through the luminal membranes of intestinal epithelial cells primarily as dipeptides, tripeptides, and free amino acids.

- Mechanism:

- Dipeptides and Tripeptides: Absorbed via a co-transport mechanism with H+ (PEPT1 transporter) into the enterocyte. Once inside, they are further hydrolyzed into amino acids by intracellular peptidases.

- Amino Acids: Absorbed by several specific carrier systems. Many of these are sodium co-transport mechanisms, similar to glucose. A specific transport protein binds both the amino acid/peptide and a sodium ion. The sodium ion then moves down its electrochemical gradient into the cell, pulling the amino acid/peptide along with it.

- Some amino acids are also transported by facilitated diffusion.

- Ultimately, almost all proteins enter the portal blood as free amino acids.

5. Absorption of Fats

- Micelles: The digested products of fat (monoglycerides, fatty acids, cholesterol) are relatively insoluble in water. They are solubilized and transported to the brush border in the form of micelles, which are small complexes formed from bile salts and digested fats.

- Efficiency: The presence of an abundance of bile micelles is crucial; about 97% of fat is absorbed with them. In their absence, only 40-50% can be absorbed.

- Process: At the brush border, monoglycerides and fatty acids passively diffuse out of the micelles and into the enterocyte. Bile salts are mostly reabsorbed further down in the ileum.

- Inside Enterocytes: Once inside the enterocyte, monoglycerides and fatty acids are re-esterified to form triglycerides. These triglycerides, along with cholesterol and phospholipids, are then packaged with proteins into larger lipoproteins called chylomicrons.

- Chylomicron Transport: Chylomicrons are too large to enter the blood capillaries directly. They are exocytosed from the enterocytes and enter the lacteals (lymphatic capillaries) within the villi, eventually reaching the systemic circulation via the lymphatic system.

- Short- and Medium-Chain Fatty Acids: A notable exception. These smaller fatty acids (e.g., from butterfat) are more water-soluble. They are absorbed directly into the portal blood rather than being re-esterified and transported via lymphatics.

IV. Absorption in the Large Intestine

- Volume: About 1500 ml of chyme pass through the ileocecal valve into the large intestine each day.

- Primary Role: The most crucial function of the colon is the absorption of water and electrolytes from this chyme.

- Result: This process concentrates the remaining waste into feces.

- Output: Approximately 100 ml of fluid are excreted as feces.

- Ion Absorption: Nearly all ions are absorbed, leaving only 1-5 mEq each of Na+ and Cl- to be lost in the feces.

- Location: Most absorption occurs in the proximal half of the large intestine (absorbing colon).

- Storage: The distal colon functions principally for feces storage (storage colon).

Mechanism of Absorption in Large Intestine:

- Capacity: The large intestine can absorb up to 5-8 liters of fluid and electrolytes daily.

- Sodium Absorption: The mucosa of the large intestine has a high capability for active absorption of Na+.

- Electrical Gradient: This active Na+ absorption creates an electrical potential gradient across the mucosa.

- Chloride Absorption: This electrical gradient drives chloride (Cl-) absorption.

- Tight Junctions: The epithelial cells of the large intestine have very tight junctions, which prevent the back-diffusion of Na+, helping to maintain a strong electrical gradient.

- Aldosterone: The presence of large quantities of aldosterone (a hormone) significantly enhances the absorption of Na+ in the colon.

- Bicarbonate Secretion: The large intestine mucosa also actively secretes bicarbonate ions (HCO3-) in exchange for chloride ions.

- Water Absorption: Water is absorbed passively due to the osmotic gradient created by the active absorption of Na+ and other solutes.

V. Composition of Feces

- Water Content: Normally about three-fourths water.

- Solid Matter: About one-fourth solid matter.

- Components of Solid Matter:

- 30% dead bacteria.

- 10-20% fat.

- 10-20% inorganic matter.

- 2-3% protein.

- 30% undigested roughage from food (e.g., cellulose) and dried constituents of digestive juices (e.g., bile pigment, sloughed epithelial cells).

- Components of Solid Matter:

- Color: The brown color of feces is caused by stercobilin and urobilin, which are derivatives of bilirubin (a bile pigment).

- Odor: The characteristic odor is principally caused by products of bacterial action on unabsorbed food residues.

VI. Disorders of the GIT

A. Gastrointestinal Obstruction

Definition: Blockage of the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract.

Causes:

- Cancer: Tumors can grow and physically block the lumen.

- Fibrotic Constriction: Scarring due to ulceration (e.g., peptic ulcers) or peritoneal adhesions (bands of scar tissue) can narrow the lumen.

- Spasm of a Segment of the Gut: Intense, prolonged contraction of a segment of the intestinal wall.

- Paralysis of a Segment of the Gut (Ileus): Loss of normal propulsive motility, leading to functional obstruction.

Effects: Depend significantly on the point of obstruction (e.g., small bowel obstruction vs. large bowel obstruction). Can lead to distention, pain, vomiting, and compromised blood supply.

B. Nausea

Definition: A conscious recognition of subconscious excitation in an area of the medulla closely associated with or part of the vomiting center. It is often a prodrome (precursor) of vomiting, but not always.

Causes:

- Irritative Impulses from the Gastrointestinal Tract: e.g., distention, inflammation, toxins.

- Impulses from the Lower Brain Associated with Motion Sickness: e.g., vestibular input from inner ear.

- Impulses from the Cerebral Cortex: Can be psychological (e.g., foul smells, disturbing sights) or anticipatory.

C. Gases in the GIT ("Flatus")

- Volume: About 7-10 liters of gas can occur in the large intestine daily, but only about 0.6 liters are typically passed through the anus. The rest is absorbed into the blood and expelled through the lungs.

- Three Main Sources:

- Swallowed Air: Air ingested during eating and drinking (aerophagia).

- Gases Formed in the Gut as a Result of Bacterial Action: Fermentation of undigested carbohydrates by colonic bacteria produces gases like hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide.

- Gases that Diffuse from the Blood into the GIT: For example, nitrogen and oxygen can diffuse from the blood into the intestinal lumen.

- Effect of Certain Foods: Certain foods are known to cause greater expulsion of flatus (e.g., beans, cabbage, onion, cauliflower, corn, and irritant foods like vinegar) because they contain high amounts of fermentable carbohydrates that are broken down by gut bacteria.

- Excess Expulsion: Excessive gas expulsion can result from irritation of the large intestine, which promotes rapid peristaltic expulsion of gases through the anus before they can be absorbed into the blood.

I. Disorders of Swallowing and of the Esophagus

These disorders primarily affect the initial stages of food passage, leading to difficulty moving food from the mouth to the stomach.

1. Paralysis of the Swallowing Mechanism

This condition involves the inability to initiate or complete the swallowing reflex due to impairment of the nervous or muscular components involved.

- Causes:

- Neurological Damage: Damage to the 5th (Trigeminal), 9th (Glossopharyngeal), and 10th (Vagus) cranial nerves, which are essential for coordinating swallowing. Damage to the swallowing center in the brainstem, as seen in conditions like poliomyelitis (viral infection affecting motor neurons) or encephalitis (brain inflammation).

- Muscular Disorders:

- Muscle dystrophy: A group of genetic diseases that cause progressive weakness and loss of muscle mass.

- Myasthenia gravis: An autoimmune neuromuscular disease leading to fluctuating muscle weakness and fatigue.

- Botulism: A rare but serious illness caused by a toxin that blocks nerve function, leading to muscle paralysis.

2. Achalasia and Megaesophagus

- Achalasia: Characterized by the failure of the Lower Esophageal Sphincter (LES) to relax properly during swallowing. This is a result of damage to or absence of the myenteric plexus ganglia (nerve cells) in the esophageal wall at the LES.

- Megaesophagus: Due to the persistent failure of the LES to relax, food accumulates in the esophagus, leading to its significant dilation (enlargement) over time. This chronic retention of food can cause irritation, infection, and malnutrition.

II. Disorders of the Stomach

These disorders affect the stomach's ability to store, digest, and move food into the small intestine.

Gastritis

Definition: Inflammation of the gastric mucosa (lining of the stomach).

Causes: Can be acute or chronic, caused by factors such as bacterial infection (e.g., Helicobacter pylori), excessive alcohol consumption, prolonged use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), stress, or autoimmune reactions.

Gastric Atrophy

Definition: A chronic condition where the gastric mucosa thins and loses its normal glandular structures. It often follows chronic gastritis, particularly autoimmune gastritis or long-standing H. pylori infection.

Consequences: Reduced acid and intrinsic factor secretion, leading to malabsorption of vitamin B12 (pernicious anemia).

Peptic Ulcer

Definition: An open sore that develops on the lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer) or the first part of the small intestine (duodenal ulcer).

Causes: Primarily caused by Helicobacter pylori infection and/or the use of NSAIDs, which disrupt the protective mucosal barrier, allowing gastric acid and pepsin to damage the underlying tissue.

III. Disorders of the Small Intestine

The small intestine is crucial for digestion and absorption. Disorders here lead to malabsorption and nutrient deficiencies.

1. Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Failure

- Pancreatitis: Inflammation of the pancreas.

- Pancreatic Failure: A condition where the pancreas does not produce enough digestive enzymes. This often results from chronic pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, or pancreatic surgery.

- Consequence: Leads to severe malabsorption of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates, causing steatorrhea, weight loss, and nutritional deficiencies.

2. Malabsorption by the Small Intestinal Mucosa—Sprue

- Definition: A general term for several diseases characterized by decreased absorption of nutrients by the small intestinal mucosa.

- Types:

- Nontropical Sprue (Celiac Disease): An autoimmune disorder triggered by gluten ingestion, leading to damage of the small intestinal villi and impaired absorption.

- Tropical Sprue: A chronic condition of unknown cause (possibly infectious) that occurs in tropical regions, also leading to malabsorption.

- Clinical Features:

- Early Stage: Intestinal absorption of fat is often more impaired than absorption of other digestive products. This leads to steatorrhea (excess fats in the stools).

- Severe Sprue: Absorption of proteins, carbohydrates, calcium, vitamin K, folic acid, and vitamin B12 is also impaired.

- Resulting Deficiencies and Symptoms:

- Severe nutritional deficiency: Often leading to wasting of the body (cachexia).

- Osteomalacia: Demineralization of the bones due to lack of calcium (and often vitamin D).

- Inadequate blood coagulation: Caused by lack of vitamin K.

- Macrocytic anemia: Of the pernicious anemia type, due to impaired absorption of folic acid and/or vitamin B12.

IV. Disorders of the Large Intestine

These disorders primarily affect water absorption, stool consistency, and bowel motility.

1. Constipation

Definition: Slow movement of feces through the large intestine.

Characteristics: Often associated with large quantities of dry, hard feces in the descending colon that accumulate due to over-absorption of fluid (due to longer transit time).

Causes: Insufficient fiber, inadequate fluid intake, lack of physical activity, certain medications, ignoring the urge to defecate.

2. Megacolon (Hirschsprung's Disease)

Mechanism: Characterized by the lack of or deficiency of ganglion cells in the myenteric plexus in a segment of the sigmoid colon (or other parts of the colon).

Consequence: Due to the absence of these nerve cells, the affected segment of the colon cannot relax or contract effectively. Neither defecation reflexes nor strong peristaltic motility can occur in this area.

Result: The aganglionic sigmoid colon itself becomes small and almost spastic, while feces accumulate proximal (upstream) to this affected area, causing massive dilation and enlargement of the ascending, transverse, and descending colons (megacolon).

3. Diarrhea

Definition: Rapid movement of fecal matter through the large intestine. This reduced transit time results in decreased absorption of water and electrolytes, leading to loose, watery stools.

Causes:

- Enteritis: Inflammation of the intestinal tract, usually caused by a virus or bacteria. This inflammation can increase secretion and motility while impairing absorption.

- Psychogenic Diarrhea: Excessive stimulation of the parasympathetic nervous system (e.g., due to stress, anxiety, or emotional factors) can increase intestinal motility and secretion.

- Ulcerative Colitis: An inflammatory bowel disease where extensive areas of the walls of the large intestine become inflamed and ulcerated. This leads to increased secretion, impaired absorption, and often bloody diarrhea.

V. General Disorders of the Gastrointestinal Tract

These are broader issues that can affect any part of the GI tract.

1. Gastrointestinal Obstruction

Definition: A blockage that prevents the normal passage of food or waste through the GI tract.

Causes:

- (1) Cancer: Tumors can grow and physically block the lumen.

- (2) Fibrotic constriction: Due to chronic inflammation (e.g., from ulcers) or peritoneal adhesions (bands of scar tissue forming after surgery or inflammation).

- (3) Spasm of a segment of the gut: Intense, sustained contraction that can temporarily block passage.

- (4) Paralysis of a segment of the gut (Paralytic Ileus): Loss of peristaltic movement in a section of the intestine, often due to abdominal surgery, inflammation, or certain medications.

Effects (Depend on the Point of Obstruction):

- Obstruction at the pylorus (stomach outlet): Causes acid vomitus (containing stomach contents).

- Obstruction below the duodenum: Causes neutral or basic vomitus (containing intestinal contents mixed with digestive juices).

- High obstruction (e.g., small intestine): Causes extreme vomiting with less constipation initially.

- Low obstruction (e.g., large intestine): Causes extreme constipation with less vomiting (or vomiting that occurs much later).

2. Nausea

Definition: An unpleasant sensation that typically precedes vomiting, but doesn't always result in it.

Mechanism: A conscious recognition of subconscious excitation in an area of the medulla closely associated with or part of the vomiting center.

Causes:

- (1) Irritative impulses from the GI tract: E.g., overdistention, inflammation, or toxins.

- (2) Impulses from the lower brain associated with motion sickness: Originating from the vestibular system.

- (3) Impulses from the cerebral cortex: Initiating vomiting due to psychological factors, unpleasant sights/smells, or fear.

3. Vomiting (Emesis)

Definition: The means by which the upper gastrointestinal tract rapidly rids itself of its contents when excessively irritated, over-distended, or over-excitable.

Strong Stimuli: Excessive distention or irritation of the duodenum is an especially strong stimulus for vomiting.

Sensory Signals: Originate mainly from the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and upper portions of the small intestines.

Nervous Regulation:

- Sensory Fibers: Travel through vagal and sympathetic pathways to the vomiting center in the brainstem (medulla oblongata).

- Motor Fibers: Return through cranial nerves (5th, 7th, 9th, 10th, and 12th) and spinal nerves to the diaphragm and abdominal muscles.

Vomiting Act (Physiological Sequence):

- Antiperistalsis: Reverse peristaltic waves often begin in the small intestine, pushing contents backward into the stomach.

- Prodromal Phase:

- Deep breath is taken.

- Hyoid bone and larynx are raised, pulling the upper esophageal sphincter open.

- Glottis closes to prevent aspiration into the lungs.

- Soft palate lifts to close the posterior nares.

- Expulsive Phase:

- Strong downward contraction of the diaphragm occurs simultaneously with forceful contraction of all the abdominal wall muscles. This squeezes the stomach between the diaphragm and abdominal muscles, dramatically increasing intragastric pressure.

- Finally, the lower esophageal sphincter relaxes, allowing the gastric contents to be expelled upward through the esophagus and out of the mouth.

4. Chemoreceptor Trigger Zone (CTZ)

- Location: Bilaterally on the floor of the fourth ventricle in the brain.

- Function: This area is outside the blood-brain barrier, making it sensitive to chemical substances in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid. It can directly stimulate the vomiting center.

- Stimuli:

- Drugs: Such as morphine, apomorphine, digitalis (used for heart conditions), chemotherapy agents.

- Motion Sickness: Rapidly changing directions of motion can stimulate this area indirectly through impulses from the vestibular labyrinth in the inner ear.

5. Gases in the GIT ("Flatus")

- Quantity: About 7-10 liters of gas occur in the large intestine each day, but only about 0.6 liters are typically passed through the anus. The rest is absorbed into the blood and expelled through the lungs.

- Three Main Sources:

- (1) Swallowed air (aerophagia): During eating, drinking, or talking.

- (2) Gases formed in the gut as a result of bacterial action: Fermentation of undigested carbohydrates (e.g., fiber).

- (3) Gases that diffuse from the blood into the GIT: Less significant contributor.

- Composition of Flatus: Primarily includes nitrogen (from swallowed air), carbon dioxide, methane, and hydrogen (produced by bacteria). Oxygen is usually absorbed rapidly.

- Foods Causing More Flatus: Certain foods like beans, cabbage, onion, cauliflower, corn, and some irritant foods (e.g., vinegar) cause greater expulsion of flatus because they contain fermentable carbohydrates that are not fully digested in the small intestine, leading to increased bacterial gas production in the colon.

- Excess Expulsion: Can also result from irritation of the large intestine, which promotes rapid peristaltic expulsion of gases through the anus before they can be absorbed.

Digestion, Absorption & Disorders Quiz

Systems Physiology

Enter your details to begin the examination.

🛡️ Privacy Note: Results are for tracking and certification purposes only.

Digestion, Absorption & Disorders Quiz

Systems Physiology

Preparing questions...

Exam Completed!

See your performance breakdown below.