Blood Physiology: Introduction

Introduction to Blood

Blood is often described as a unique connective tissue, though it differs significantly from other connective tissues like bone or cartilage. Its uniqueness stems from its cellular components being suspended in a liquid extracellular matrix (plasma) rather than being anchored to solid fibers. This fluidity is crucial for its transport functions.

It is the only fluid tissue in the body, continuously circulating within the closed system of the cardiovascular system (heart, blood vessels). It is a complex, viscous fluid that accounts for approximately 8% of total body weight in an average adult (e.g., about 5-6 liters in males, 4-5 liters in females).

Origin: All blood cells originate from hematopoietic stem cells in the red bone marrow.

Why is it essential for life?

- Blood serves as the body's primary transport and communication medium, ensuring that all cells receive necessary resources and waste products are efficiently removed. Without its continuous circulation, cells would rapidly cease to function due to lack of oxygen and nutrients, and the accumulation of toxic metabolic byproducts.

- It acts as a dynamic internal environment, constantly adapting to the body's changing needs and maintaining homeostasis (the stable internal conditions required for survival).

Overview of Major Roles of Blood

1. Distribution/Transportation

Blood acts as the delivery system for the body:

- Respiratory Gases:

- Carries oxygen from the lungs (where it's loaded onto hemoglobin in red blood cells) to all body tissues and cells for cellular respiration.

- Transports carbon dioxide, a waste product of cellular respiration, from body cells back to the lungs for exhalation (dissolved in plasma, bound to hemoglobin, or as bicarbonate ions).

- Nutrients: Delivers absorbed nutrients (e.g., monosaccharides like glucose, amino acids, fatty acids, glycerol, vitamins, minerals) from the digestive tract to the liver first, and then to all body cells for energy, growth, and repair.

- Hormones: Acts as the "circulatory highway" for endocrine hormones, transporting them from their sites of production (endocrine glands) to their specific target organs or cells throughout the body, regulating diverse physiological processes.

- Metabolic Wastes: Collects and transports metabolic waste products, such as urea (from protein metabolism) and uric acid (from nucleic acid metabolism) to the kidneys for excretion in urine, and lactic acid (from anaerobic respiration) to the liver for conversion.

2. Regulation

Blood plays a pivotal role in maintaining the stability of the interstitial fluid (homeostasis):

- Body Temperature: Blood possesses a high heat capacity due to its water content. It absorbs heat generated by metabolically active tissues (e.g., muscles) and distributes it throughout the body. By regulating blood flow to the skin, it can either dissipate excess heat (vasodilation) or conserve heat (vasoconstriction) to maintain a stable core body temperature.

- pH Levels: Crucial for maintaining the extremely narrow and vital physiological pH range of 7.35-7.45. It achieves this through various buffer systems present in plasma proteins and within red blood cells (e.g., bicarbonate buffer system, phosphate buffer system, protein buffer system). These buffers can accept or donate hydrogen ions to resist drastic changes in acidity or alkalinity.

- Fluid Volume and Blood Pressure: Blood plasma proteins, particularly albumin, exert significant osmotic pressure (colloid osmotic pressure). This pressure draws water from the interstitial fluid back into the capillaries, maintaining proper fluid volume within the circulatory system and helping to prevent edema (swelling of tissues). Maintaining adequate blood volume is directly linked to maintaining sufficient blood pressure for tissue perfusion.

-

Electrolyte Balance: Transports various electrolytes (

Na+,K+,Ca2+,Cl-,HCO3-) which are vital for nerve impulse transmission, muscle contraction, and fluid balance.

3. Protection

Blood provides defense mechanisms against blood loss and foreign invaders:

- Prevention of Blood Loss (Hemostasis): Initiates a rapid and efficient series of events when a blood vessel is damaged. This process, called hemostasis, involves the aggregation of platelets (thrombocytes) and the activation of clotting factors (plasma proteins) to form a fibrin clot, sealing the injured vessel and preventing excessive hemorrhage.

- Prevention of Infection:

- Leukocytes (White Blood Cells): Are the mobile units of the immune system. They identify and destroy pathogens (bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites) and remove damaged or abnormal cells (e.g., cancer cells, dead cells). Different types of leukocytes have specialized roles in this defense.

- Antibodies: Specific proteins (immunoglobulins) produced by certain lymphocytes that target and neutralize specific pathogens or toxins.

- Complement Proteins: A group of plasma proteins that, when activated, can lyse microorganisms, enhance phagocytosis, and contribute to inflammation.

Physical Characteristics

Appearance & Texture

- Oxygen-rich blood: (typically arterial) is a bright, scarlet red. This vibrant color is due to hemoglobin picking up oxygen in the lungs (oxyhemoglobin).

- Oxygen-poor blood: (typically venous) is a darker, duller red, sometimes described as brick-red or maroon. This is because hemoglobin has released its oxygen (deoxyhemoglobin). Note: Venous blood is never blue, despite how veins appear through the skin.

Blood is about 5 times more viscous (thicker/stickier) than water, primarily due to RBCs and plasma proteins.

Properties

Slightly alkaline (basic), maintained tightly between 7.35 and 7.45.

- pH < 7.35 = Acidosis

- pH > 7.45 = Alkalosis

Circulates at ~38°C (100.4°F), slightly higher than body temperature, to absorb and distribute metabolic heat.

Metallic taste (iron content) and faint characteristic odor.

Volume: The average adult has approximately 5-6 liters (1.5 gallons), constituting 7-8% of total body weight.

Clinical Significance: Significant deviations (hemorrhage, fluid overload) severely compromise tissue perfusion.

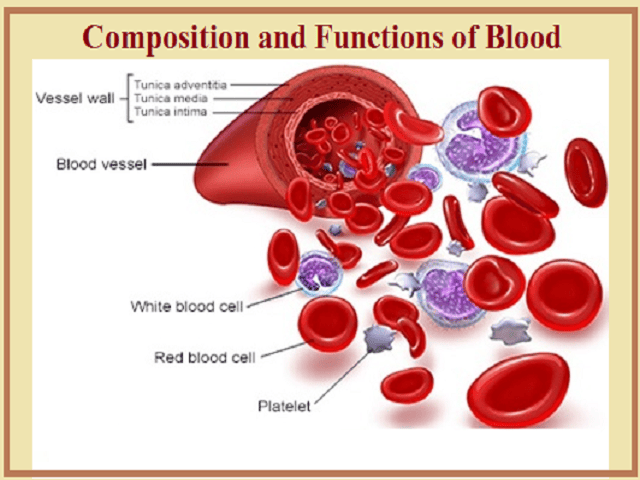

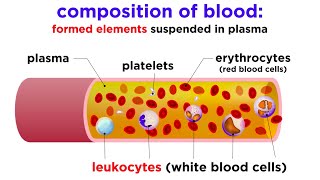

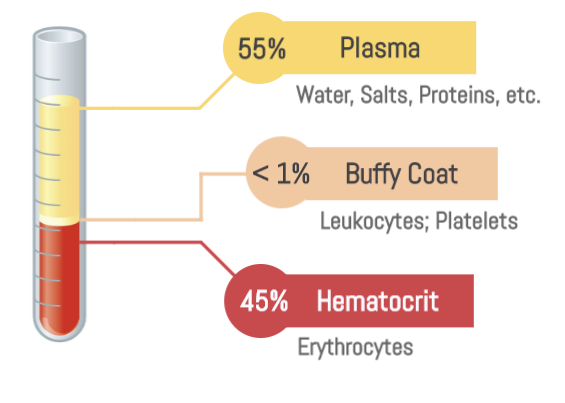

Composition of Blood: The Two Major Components

When a sample of blood is collected and centrifuged (spun at high speed), its components separate into distinct layers due to differences in density. This separation reveals two main components:

55%

45%

1. Plasma (Liquid Matrix)

Constitutes ~55% of total volume.

- Least dense component; forms top, yellowish-straw colored layer.

- A sticky, non-living fluid matrix.

- (Detailed composition covered in Objective 1.3)

2. Formed Elements (Cellular)

Constitutes ~45% of total volume (Hematocrit).

Normal Hematocrit: Males 42-52%, Females 37-47%.

-

Erythrocytes (RBCs):

Most numerous (99.9%). Dense red mass at the bottom. Responsible for O2 transport. -

The "Buffy Coat" (Top of formed elements):

Thin, whitish layer between plasma and RBCs containing:- Leukocytes (WBCs): Critical for immune defense.

- Thrombocytes (Platelets): Fragments involved in clotting.

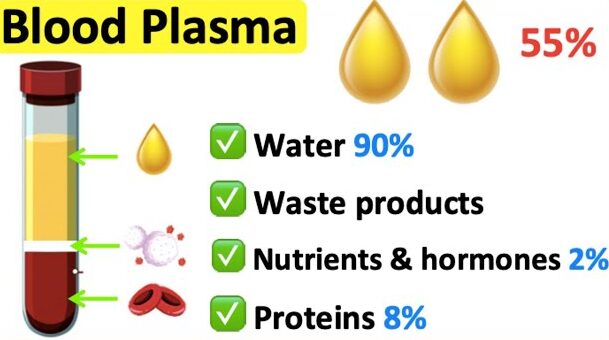

Composition and Functions of Blood Plasma

Plasma is the non-living fluid matrix of blood, accounting for approximately 55% of total blood volume. It is a complex mixture, predominantly water, with a vast array of dissolved solutes, many of which are vital for maintaining homeostasis.

Composition of Blood Plasma

1. Water (approx. 90% by weight)

This is the major component of plasma, serving as the solvent for all other plasma constituents.

Function:

- Acts as the medium for dissolving and suspending solutes.

- Excellent heat absorber and distributor, contributing to thermoregulation.

- Provides the fluidity necessary for blood circulation.

2. Plasma Proteins (approx. 8% by weight)

These are the most abundant solutes in plasma by weight and are almost entirely produced by the liver (with the exception of gamma globulins/antibodies). They are not taken up by cells to be used as metabolic fuels or nutrients (unlike other plasma solutes), but rather remain in the blood.

Key Functions (collectively): Contribute to osmotic pressure, act as buffers, transport substances, and play roles in blood clotting and immunity.

Albumin

Most abundant plasma protein.

Main contributor to plasma osmotic pressure: It acts like a sponge, drawing water from the interstitial fluid into the bloodstream, thereby maintaining blood volume and blood pressure.

Important buffer: Helps to maintain blood pH.

Carrier protein: Transports various substances in the blood, including certain hormones (e.g., thyroid hormones, steroid hormones), fatty acids, and some drugs.

Globulins

A diverse group of proteins.

- Transport proteins that bind to and transport lipids (forming lipoproteins), metal ions (e.g., transferrin for iron), and fat-soluble vitamins.

- Some are involved in immune responses.

- Also known as antibodies or immunoglobulins.

- Produced by plasma cells (derived from B lymphocytes), not the liver.

- Function: Critical components of the immune system, recognizing and attacking pathogens.

Fibrinogen

A large plasma protein produced by the liver.

Function: Key component of the blood clotting cascade. It is converted into fibrin, which forms the meshwork of a blood clot.

Other Plasma Proteins: Includes enzymes, complement proteins (involved in immunity), and various regulatory proteins.

Other Solutes

3. Nutrients (approx. 1%)

Substances absorbed from the digestive tract and transported to body cells.

Examples: Glucose (blood sugar), amino acids, fatty acids, glycerol, vitamins, cholesterol.

4. Electrolytes (Ions - approx. 1%)

Inorganic salts, primarily Na+, Cl-, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, HCO3-, HPO42-, and SO42-.

Most abundant plasma solutes by number.

- Maintain plasma osmotic pressure.

- Crucial for buffering blood pH.

- Essential for nerve impulse transmission, muscle contraction, and enzyme activity.

- Electrolyte balance is vital for body fluid distribution.

5. Gases

Dissolved O2, CO2, and N2.

Function: Transport of respiratory gases. (Note: Most are transported by RBCs, but a small amount dissolves in plasma).

6. Hormones

Steroid and protein-based hormones transported to target cells to regulate physiology.

7. Waste Products

Byproducts of metabolism transported to kidneys/lungs/liver.

Examples: Urea, uric acid, creatinine, ammonium salts.

Functions of Blood Plasma (Summary)

- Transport: Serves as the primary medium for transporting nutrients, gases, hormones, metabolic wastes, and drugs throughout the body.

-

Regulation:

- Osmotic Pressure & Fluid Balance: Plasma proteins, especially albumin, maintain the body's fluid volume and osmotic pressure.

- pH Balance: Plasma proteins and bicarbonate ions act as buffers.

- Temperature Regulation: Water content helps distribute and dissipate heat.

- Protection: Contains antibodies and complement proteins for immunity, and clotting factors (like fibrinogen) to prevent blood loss.

Haematopoiesis: Formation of Blood Cells

Haematopoiesis (Gr. haima = blood; poiesis = to make) is the process of generating all of the cellular components of blood from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).

This includes the formation of:

- Erythropoiesis: Production of Erythrocytes (red blood cells).

- Leukopoiesis: Production of Leukocytes (white blood cells).

- Thrombopoiesis: Production of Thrombocytes (platelets).

Significance

1. Maintenance of Blood Cell Homeostasis:

Blood cells have finite lifespans (e.g., RBCs ~120 days, platelets ~10 days, neutrophils ~hours to days). Hematopoiesis ensures that old or damaged cells are constantly replaced by new ones, maintaining stable numbers of each cell type.

2. Response to Physiological Demands:

The rate of hematopoiesis can be dramatically increased in response to specific physiological needs, such as:

- Anemia: Increased erythropoiesis to compensate for low red blood cell count or oxygen-carrying capacity.

- Infection: Increased leukopoiesis (especially granulopoiesis) to combat pathogens.

- Hemorrhage: Increased production of red blood cells and platelets to replace lost blood volume and ensure clotting.

3. Repair and Regeneration: Provides the cells necessary for tissue repair, immune surveillance, and defense against injury and disease.

4. Adaptation: Allows the body to adapt to changes in environmental conditions (e.g., higher altitude, requiring more RBCs).

Sites of Hematopoiesis

1. Embryonic Hematopoiesis

- Yolk Sac: Begins very early in embryonic development (around 3rd week of gestation). Primitive red blood cells are formed here.

- Aorta-Gonad-Mesonephros (AGM) region: A crucial site for the emergence and expansion of definitive HSCs.

- Liver: Becomes the primary hematopoietic organ during the second trimester of fetal development.

- Spleen: Also contributes significantly to hematopoiesis during fetal life.

2. Fetal Hematopoiesis

- Liver and Spleen: Are the dominant sites from the second trimester until near birth.

- Bone Marrow: Begins to take over as the primary site during the late fetal period.

3. Adult Hematopoiesis

Red Bone Marrow:

After birth and throughout adulthood, red bone marrow is the sole site of normal hematopoiesis.

- Location: Found primarily in the axial skeleton (skull, vertebrae, ribs, sternum), pelvic girdle, and the epiphyses (ends) of the humerus and femur.

- Composition: Composed of a vascular compartment and a hematopoietic compartment, including hematopoietic stem cells, progenitor cells, developing blood cells, and a stroma (supportive tissue including reticular cells, adipocytes, macrophages).

Yellow Bone Marrow:

In adults, much of the red bone marrow is replaced by yellow bone marrow (composed mainly of fat cells), which is generally quiescent in hematopoiesis but can convert back to red marrow in cases of extreme demand (e.g., severe hemorrhage).

Extramedullary Hematopoiesis: In certain pathological conditions (e.g., severe bone marrow failure, chronic myeloproliferative disorders), the liver and spleen can reactivate their fetal hematopoietic capacity, leading to blood cell production outside the bone marrow.

Role of Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs)

At the pinnacle of the hematopoietic system are the Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs), the remarkable cells responsible for generating all mature blood cells. Understanding HSCs is fundamental to comprehending blood cell formation.

Characteristics of HSCs

1. Pluripotency (Multipotency)

HSCs are pluripotent (more accurately, multipotent). They have the unique ability to differentiate into all types of blood cells (RBCs, WBCs, Platelets). They cannot, however, differentiate into cells of other tissues (like neurons), which is why they are not considered totipotent.

2. Self-Renewal

HSCs undergo asymmetric cell division: one daughter cell remains an undifferentiated stem cell (replenishing the pool) and the other commits to differentiation. This ensures a lifelong supply. Without this, the stem cell pool would eventually deplete.

3. Quiescence

Most HSCs in the marrow exist in a relatively quiescent (resting) state, dividing infrequently to protect from DNA damage and exhaustion. However, they can be rapidly activated in response to stress (infection, hemorrhage).

4. Rare Population

HSCs are an extremely rare population of cells within the bone marrow, estimated to be less than 0.01% of all bone marrow cells.

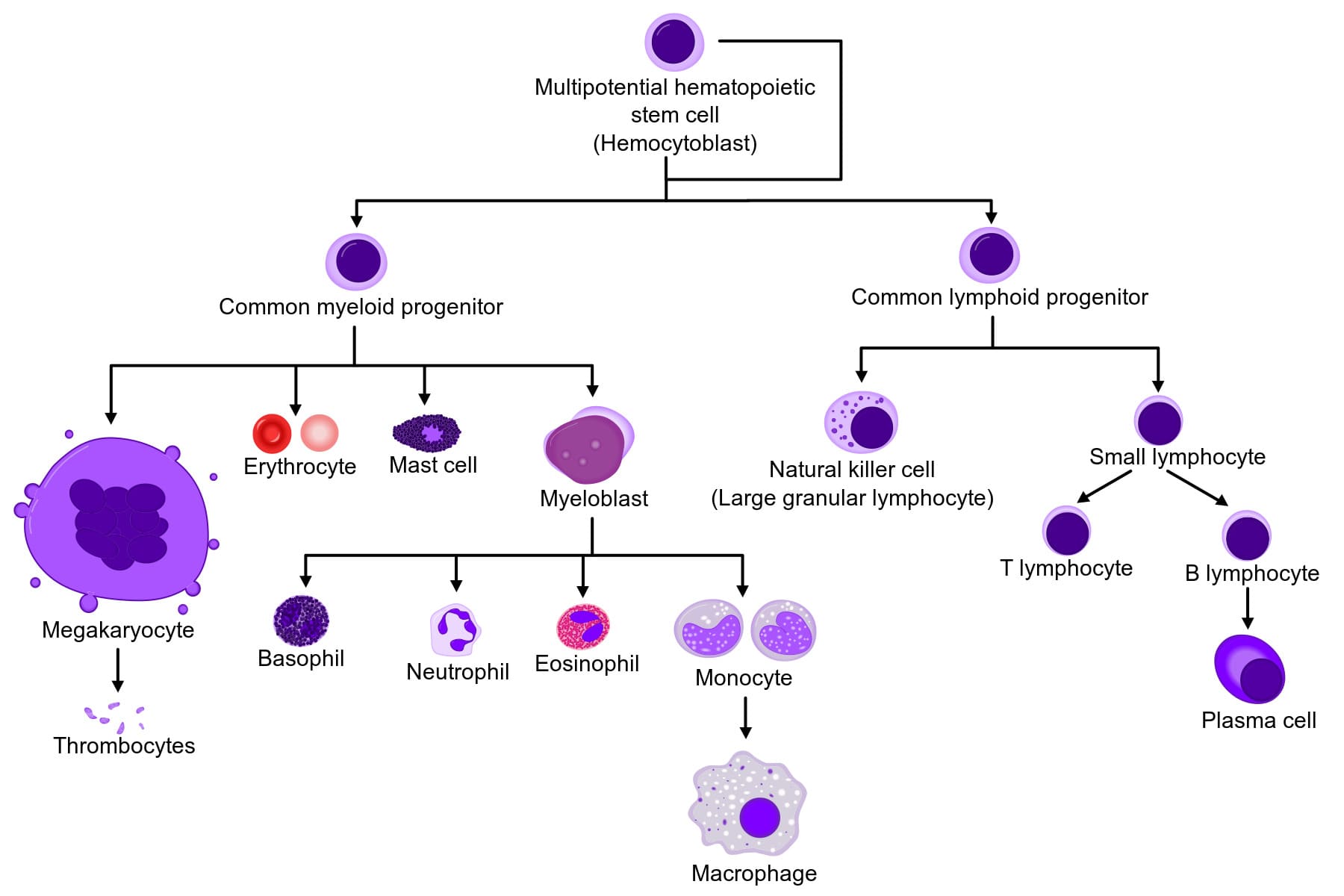

Differentiation Pathways: The "Hematopoietic Tree"

HSCs don't directly differentiate into mature blood cells. Instead, they undergo a series of commitment steps, forming progenitor cells that have more restricted differentiation potential.

Commitment to Lineage

Upon commitment, an HSC differentiates into one of two major progenitor cell types:

Common Myeloid Progenitor (CMP)

Gives rise to most cells involved in innate immunity and oxygen transport.

- Erythrocytes (RBCs): via Erythropoiesis.

- Megakaryocytes: leading to Platelets via Thrombopoiesis.

- Granulocytes: Neutrophils, Eosinophils, Basophils.

- Monocytes: Mature into macrophages in tissues.

- (Some also include mast cells from this lineage).

Common Lymphoid Progenitor (CLP)

Gives rise to cells primarily involved in adaptive immunity.

- B Lymphocytes: Mature into plasma cells and produce antibodies.

- T Lymphocytes: Involved in cell-mediated immunity.

- Natural Killer (NK) cells: Important components of innate immunity.

Significance of HSCs

- Lifelong Blood Production: Crucial for maintaining the continuous supply of all blood cell types throughout an individual's life.

- Therapeutic Potential: HSCs are the basis for bone marrow transplantation (more accurately, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation), a life-saving procedure used to treat various blood cancers (leukemias, lymphomas), bone marrow failure syndromes (aplastic anemia), and certain genetic disorders.

Regulation and Differentiation in Hematopoiesis

Hematopoiesis is a tightly regulated process, ensuring that the production of each blood cell type matches the body's physiological demands. This regulation is primarily orchestrated by a diverse array of signaling molecules, collectively known as hematopoietic growth factors and cytokines.

Hematopoietic Growth Factors and Cytokines

What are they? These are secreted protein or glycoprotein signaling molecules that act as messengers between cells.

Mechanism: They bind to specific receptors on target cells (HSCs, progenitor cells, and developing blood cells), triggering intracellular signaling pathways that influence cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and maturation.

- Autocrine: Affecting the cell that produced them.

- Paracrine: Affecting nearby cells.

- Endocrine: Affecting distant cells via the bloodstream.

Key Regulatory Molecules

Erythropoietin (EPO)

Producer: Kidneys (90%), liver (10%).

Target: Erythroid progenitor cells (CFU-E, proerythroblasts).

Function: Stimulates erythropoiesis. Promotes proliferation/differentiation of precursors and prevents apoptosis.

Clinical: Used to treat anemia (e.g., in chronic kidney disease, chemotherapy).

Thrombopoietin (TPO)

Producer: Liver (main), kidneys, bone marrow stromal cells.

Target: Megakaryocytes and progenitors.

Function: Stimulates thrombopoiesis. Promotes maturation of megakaryocytes and platelet formation.

Clinical: Being developed for thrombocytopenia.

Colony-Stimulating Factors (CSFs)

Glycoproteins named for their ability to form "colonies" in vitro.

-

Granulocyte-CSF (G-CSF):

Produced by macrophages/endothelial cells. Target: Myeloblasts.

Stimulates neutrophil production and function. Clinical: Filgrastim used for neutropenia. -

Macrophage-CSF (M-CSF):

Produced by monocytes/fibroblasts. Target: Monocyte progenitors.

Promotes monocyte proliferation and macrophage function. -

Granulocyte-Macrophage-CSF (GM-CSF):

Produced by T cells/macrophages. Target: Granulocyte & Monocyte progenitors.

Stimulates production of both lineages and dendritic cell maturation.

Interleukins (ILs)

Cytokines with pleiotropic effects, often acting synergistically.

-

IL-3 (Multi-CSF):

Produced by T cells. Targets early multipotent progenitors (HSCs, CMPs, CLPs). Stimulates nearly all lineages. -

IL-6:

Produced by macrophages/T cells. Supports multipotent progenitors; involved in immune/acute phase response. -

IL-7:

Produced by stromal cells. Crucial for B and T lymphocyte development.

Stem Cell Factor (SCF) / c-kit Ligand

A crucial "master switch" factor produced by marrow stromal cells. It promotes survival, proliferation, and differentiation of very early stem/progenitor cells, working synergistically with many other factors.

The Bone Marrow Microenvironment (Niche): These factors act within a complex niche of stromal cells and extracellular matrix, which provides essential support and regulates HSC self-renewal vs. differentiation.

General Differentiation Pathways

Starting from the HSC, blood cells undergo commitment, proliferation, and maturation guided by the factors above.

I. Erythropoiesis (Red Blood Cell Formation)

Purpose: Produce O2-carrying RBCs.

Stimulus: Hypoxia → EPO.

1. Hematopoietic Stem Cell (HSC) → Common Myeloid Progenitor (CMP).

2. Proerythroblast: First committed cell. Large nucleus, basophilic cytoplasm (ribosome synthesis).

3. Basophilic Erythroblast: Intense blue cytoplasm. Hemoglobin synthesis begins.

4. Polychromatic Erythroblast: Grayish-blue cytoplasm (mix of ribosomes/hemoglobin). Rapid division.

5. Orthochromatic Erythroblast (Normoblast): Pink/red cytoplasm (high hemoglobin). Nucleus condenses and is ejected.

6. Reticulocyte: Anucleated immature RBC containing residual ribosomal RNA. Released into bloodstream.

7. Mature Erythrocyte: After 1-2 days in circulation, reticulum is lost. Biconcave disc.

II. Leukopoiesis (White Blood Cell Formation)

Purpose: Immune defense.

Stimulus: Infection/Inflammation → CSFs/Interleukins.

A. Myeloid Lineage (from CMP)

Granulopoiesis (Neutrophils, Eosinophils, Basophils)

- Myeloblast: First committed cell.

- Promyelocyte: Large granules appear.

- Myelocyte: Specific granules appear.

- Metamyelocyte: Nucleus indents (kidney shape).

- Band (Stab) Cell: Nucleus C or U-shaped. (Immature, seen in "left shift").

- Mature Granulocyte: Segmented nucleus.

Monopoiesis

- Monoblast → Promonocyte.

- Monocyte: Large, kidney-shaped nucleus. Circulates briefly.

- Macrophage: Differentiated monocyte in tissues.

B. Lymphoid Lineage (from CLP)

- Lymphoblast → Prolymphocyte.

- Mature Lymphocytes:

- B Lymphocytes: Mature in bone marrow.

- T Lymphocytes: Mature in thymus.

- NK Cells: Mature in marrow/spleen/thymus.

Note: T cells undergo critical maturation in the thymus.

III. Thrombopoiesis (Platelet Formation)

Purpose: Hemostasis.

Stimulus: TPO.

1. HSC → CMP → Megakaryoblast.

2. Endomitosis: DNA replication without cell division.

3. Megakaryocyte: Massive cell (up to 100µm), multi-lobed polyploid nucleus. Resides near sinusoids.

4. Platelet Formation: Megakaryocyte extends proplatelets into sinusoids, which fragment into thousands of platelets.

Blood Physiology: Introduction

Test your knowledge with these 40 questions.

Blood Physiology Quiz

Question 1/40

Quiz Complete!

Here are your results, .

Your Score

38/40

95%