Abdominal Wall Anatomy

The Abdomen

The abdomen is a crucial anatomical region of the trunk, forming the large, flexible cavity that lies between the thorax (chest) superiorly and the pelvis inferiorly. It serves as a protective housing for many of the body's vital visceral organs and plays a key role in various physiological processes.

Location:

- Superiorly: Separated from the thorax by the diaphragm, a dome-shaped musculofibrous septum.

- Inferiorly: It is continuous with the pelvis at the level of the pelvic inlet, an imaginary plane defined by the sacral promontory, arcuate line, pectineal line, and pubic crest.

Contents:

The abdominal cavity accommodates major components of several organ systems, including:

- Digestive System: Stomach, small and large intestines, liver, gallbladder, pancreas.

- Urinary System: Kidneys, ureters (most of their length).

- Reproductive System: Ovaries and uterine tubes (in females) in the inferior part of the abdomen, though primarily pelvic organs.

- Other Organs: Spleen, adrenal glands.

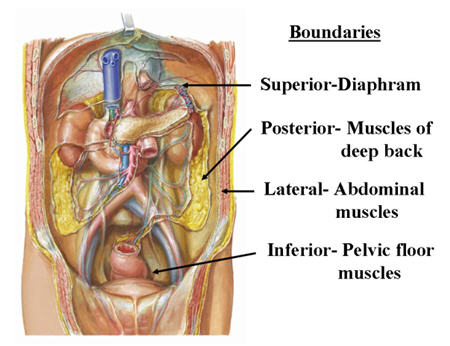

Borders of the Abdomen:

Understanding the boundaries is essential for defining this region.

- Superior Border:

- Diaphragm: The primary anatomical and physiological separator.

- Bony landmarks: The inferior margins of the 7th to 12th costal cartilages, forming the costal margin, and the xiphoid process of the sternum.

- Inferior Border:

- Bony landmarks: The pubic bone (pubic crest and pubic tubercle) anteriorly, and the iliac crests laterally.

- Vertebral Level: The inferior border generally approximates the level of the L4 vertebra posteriorly.

- Anterior Boundary: Formed by the anterior abdominal wall.

- Posterior Boundary: Formed by the posterior abdominal wall, which includes the lumbar vertebrae, psoas major, quadratus lumborum, and iliacus muscles.

Anterior Abdominal Wall

The anterior abdominal wall forms the front and sides of the abdominal cavity, extending from the thoracic cage down to the pelvis. It is a complex, multilayered structure designed to protect abdominal viscera, assist in breathing, maintain intra-abdominal pressure, and facilitate trunk movements.

Extent:

- Superiorly: Extends from the xiphoid process of the sternum and the costal margin (formed by the cartilages of ribs 7-10).

- Inferiorly: Extends down to the pubic bones and iliac crests. In the midline, it continues to the scrotum in males or the labia majora in females.

- Given its importance in protecting vital organs and its role in many bodily functions, all parts of the anterior abdominal wall are critical for examination and investigation in clinical settings. This includes visual inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation.

- Understanding its layers and landmarks is fundamental for surgical approaches, diagnosis of hernias, and assessment of abdominal pain or trauma.

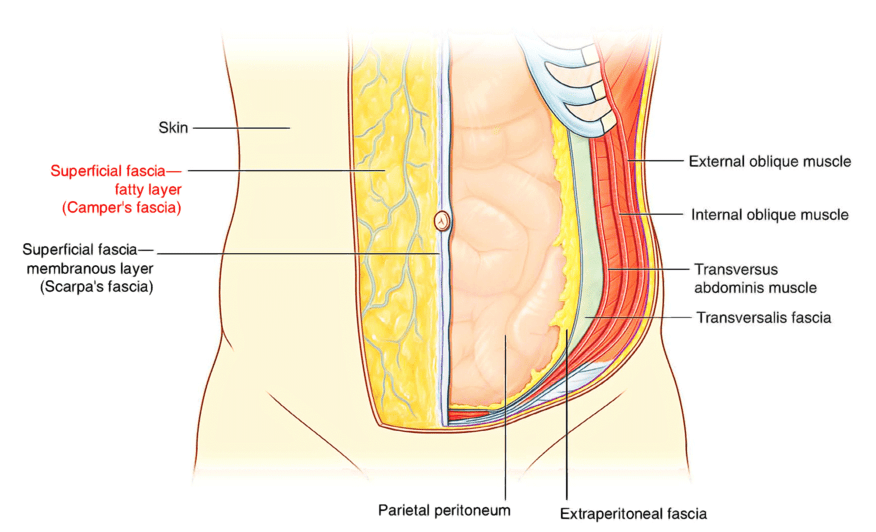

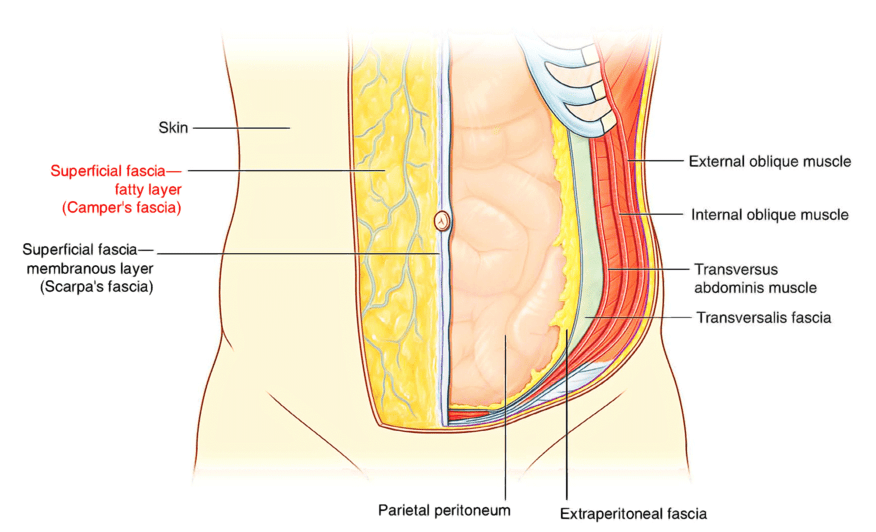

Layers of the Anterior Abdominal Wall (from superficial to deep):

- Skin: The outermost layer.

- Superficial Fascia: Composed of two layers below the umbilicus:

- Camper's Fascia (Fatty Layer): The superficial, thicker, fatty layer. Continuous with superficial fat over the rest of the body.

- Scarpa's Fascia (Membranous Layer): The deep, thin, membranous layer. It is attached to the pubic symphysis and perineal fascia (Colles' fascia), which is clinically important in containing extravasated urine or blood from perineal trauma.

- Muscles and their Aponeuroses: Three flat muscles and two vertical muscles.

- Transversalis Fascia: A thin, strong layer of fascia that lines the abdominal cavity internal to the transversus abdominis muscle.

- Extraperitoneal Fat: A variable layer of fat between the transversalis fascia and the peritoneum.

- Peritoneum: The innermost serous membrane lining the abdominal cavity.

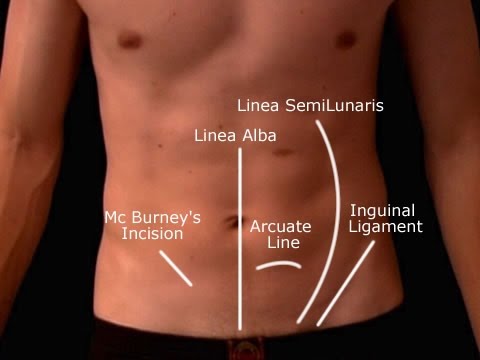

Lines and Bands of the Anterior Abdominal Wall:

These fibrous structures provide important landmarks and structural integrity to the anterior abdominal wall.

1. Linea Alba ("White Line")

- Location: A strong, fibrous raphe (seam) located precisely along the midline of the anterior abdominal wall. It extends from the xiphoid process superiorly to the pubic symphysis inferiorly.

- Formation: It is formed by the fusion of the aponeuroses of the three flat abdominal muscles (external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis) from both sides.

- Clinical Significance: It is a relatively avascular area, making it a common site for surgical incisions (e.g., midline laparotomy) as it minimizes bleeding. It is also a site where hernias (epigastric or umbilical) can occur.

2. Linea Semilunaris ("Half-Moon Line")

- Location: A curved tendinous intersection found on each side of the anterior abdominal wall. It runs vertically, extending from the tip of the 9th costal cartilage to the pubic tubercle.

- Formation: It represents the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle, where the aponeuroses of the three flat abdominal muscles merge before forming the rectus sheath.

- Clinical Significance: It is a potential site for Spigelian hernias (hernias through the linea semilunaris).

3. Linea Transversa (Tendinous Intersections)

- Description: These are three or more transverse fibrous bands or inscriptions that interrupt the rectus abdominis muscle. They are typically found at the level of the xiphoid process, umbilicus, and halfway between them.

- Function: They divide the rectus abdominis muscle into segments, contributing to its "six-pack" appearance and enhancing its mechanical advantage during contraction. They are firmly attached to the anterior layer of the rectus sheath.

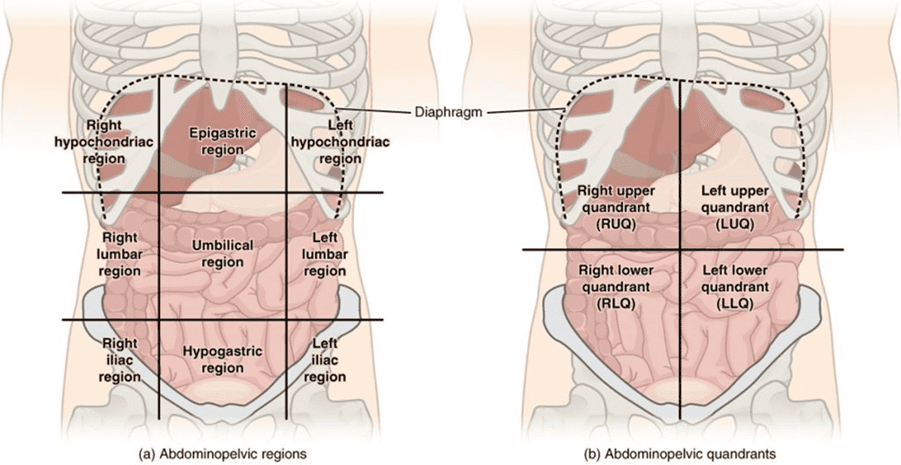

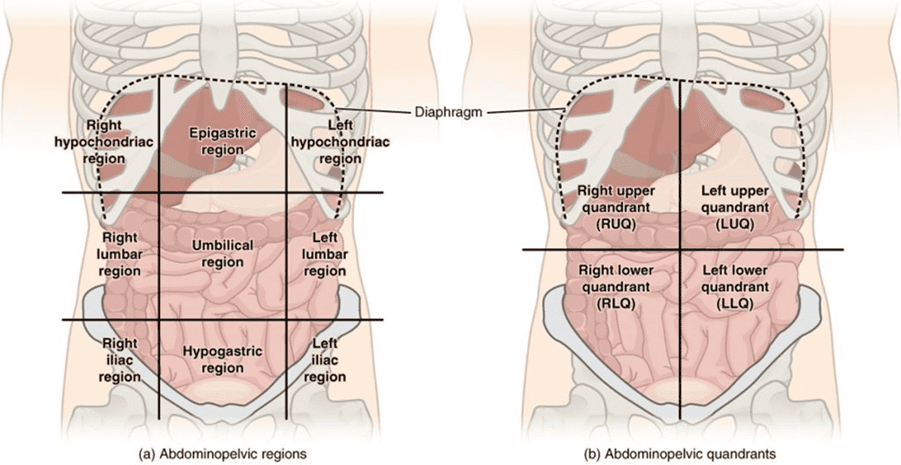

Abdominal Quadrants and Regions: Topographical Organization

To facilitate clinical description, examination, and diagnosis, the large abdominal area is divided into smaller, more manageable sections using imaginary lines on the surface of the anterior abdominal wall. There are two primary systems for this division: Quadrants and Regions.

Abdominal Quadrants:

This is a simpler, less precise system commonly used for quick clinical assessment, especially in emergency settings, to localize pain, masses, or injuries.

- Formation: It divides the abdomen into four major areas using two intersecting imaginary lines:

- Median Sagittal Plane: A vertical line that passes superiorly to inferiorly through the midline of the body, bisecting the umbilicus.

- Transumbilical Plane: A horizontal line that passes through the umbilicus, perpendicular to the median sagittal plane.

- Intersection: These two lines intersect at the umbilicus.

The Four Quadrants:

1. Right Upper Quadrant (RUQ)

Contents (Key Organs): Right lobe of liver, gallbladder, pylorus of stomach, duodenum (parts 1-3), head of pancreas, right adrenal gland, right kidney (upper part), right colic (hepatic) flexure, superior part of ascending colon.

2. Left Upper Quadrant (LUQ)

Contents (Key Organs): Left lobe of liver, spleen, most of stomach, jejunum and proximal ileum, body and tail of pancreas, left adrenal gland, left kidney (upper part), left colic (splenic) flexure, superior part of descending colon.

3. Right Lower Quadrant (RLQ)

Contents (Key Organs): Cecum, appendix, most of ileum, inferior part of ascending colon, right ovary and uterine tube (females), right ureter (abdominal part), right spermatic cord (males). Common site for pain in appendicitis.

4. Left Lower Quadrant (LLQ)

Contents (Key Organs): Sigmoid colon, inferior part of descending colon, left ovary and uterine tube (females), left ureter (abdominal part), left spermatic cord (males). Common site for pain in diverticulitis.

Abdominal Regions:

This system provides a more detailed and anatomically precise division of the abdomen into nine smaller areas. It is generally used for more specific anatomical descriptions and diagnoses.

- Formation: It divides the abdomen into nine regions using two pairs of imaginary planes:

- Two Vertical Planes:

- Right and Left Midclavicular Planes: These vertical lines are drawn inferiorly from the midpoint of each clavicle to the midpoint between the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and the pubic symphysis. They are sometimes referred to as right and left lateral planes.

- Two Horizontal Planes:

- Transpyloric Plane: An upper horizontal plane, typically located midway between the jugular notch of the sternum and the superior border of the pubic symphysis. This plane roughly corresponds to the level of the L1 vertebra and often passes through the pylorus of the stomach, the duodenojejunal junction, the neck of the pancreas, and the hila of the kidneys. (It is also often described as being midway between the xiphoid process and the umbilicus).

- Intertubercular Plane: A lower horizontal plane that passes through the tubercles of the iliac crests (the prominent anterior projections of the iliac crests). This plane roughly corresponds to the level of the L5 vertebra.

- Two Vertical Planes:

The Nine Regions and Their Typical Contents:

1. Right Hypochondriac Region

Contents: Right lobe of liver, gallbladder, right kidney (upper pole), parts of duodenum.

2. Epigastric Region

Contents: Most of the stomach, part of the liver (left lobe), pancreas, duodenum, adrenal glands, parts of the major blood vessels (aorta, IVC).

3. Left Hypochondriac Region

Contents: Spleen, part of the stomach, tail of pancreas, left kidney (upper pole), left colic (splenic) flexure.

4. Right Lateral (Lumbar) Region

Contents: Ascending colon, lower part of right kidney, parts of small intestine.

5. Umbilical Region

Contents: Small intestine (most of jejunum and ileum), transverse colon, part of the greater omentum, mesentery.

6. Left Lateral (Lumbar) Region

Contents: Descending colon, lower part of left kidney, parts of small intestine.

7. Right Inguinal (Iliac) Region

Contents: Cecum, appendix, terminal ileum, right ureter (pelvic part), right ovary/spermatic cord.

8. Hypogastric (Pubic) Region

Contents: Small intestine (coils of ileum), urinary bladder (especially when full), pregnant uterus, parts of the sigmoid colon.

9. Left Inguinal (Iliac) Region

Contents: Sigmoid colon, left ureter (pelvic part), left ovary/spermatic cord.

Layers of the Anterior Abdominal Wall (Detailed)

Understanding the distinct layers of the anterior abdominal wall is fundamental for appreciating its strength, flexibility, and surgical considerations. From superficial to deep, these layers are:

1. Skin:

- The outermost protective layer, providing sensation and acting as a barrier.

- Contains hair, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands.

- The direction of Langer's lines (cleavage lines) is important for surgical incisions, as incisions along these lines tend to heal with less scarring.

2. Superficial Fascia:

This layer lies immediately beneath the skin. Below the umbilicus, it typically divides into two distinct layers:

- Camper's Fascia (Fatty Layer):

- A superficial, typically thicker layer composed primarily of fat.

- Its thickness varies greatly among individuals and is a major determinant of abdominal girth.

- It is continuous with the superficial fat over the rest of the body.

- Scarpa's Fascia (Membranous Layer):

- A deeper, thin but strong, fibrous, membranous layer.

- It is attached inferiorly to the deep fascia of the thigh (fascia lata) just below the inguinal ligament and continuous with the superficial perineal fascia (Colles' fascia) in the perineum.

- Clinical Significance: This attachment prevents fluid (e.g., urine from a ruptured urethra or blood) from dissecting down into the thighs but allows it to spread superiorly into the anterior abdominal wall or into the perineum.

3. Deep Fascia:

- A thin, tough layer of fibrous connective tissue that covers the muscles.

- It is often not considered a separate, distinct layer in the abdominal wall, as it largely fuses with the aponeuroses of the muscles it covers.

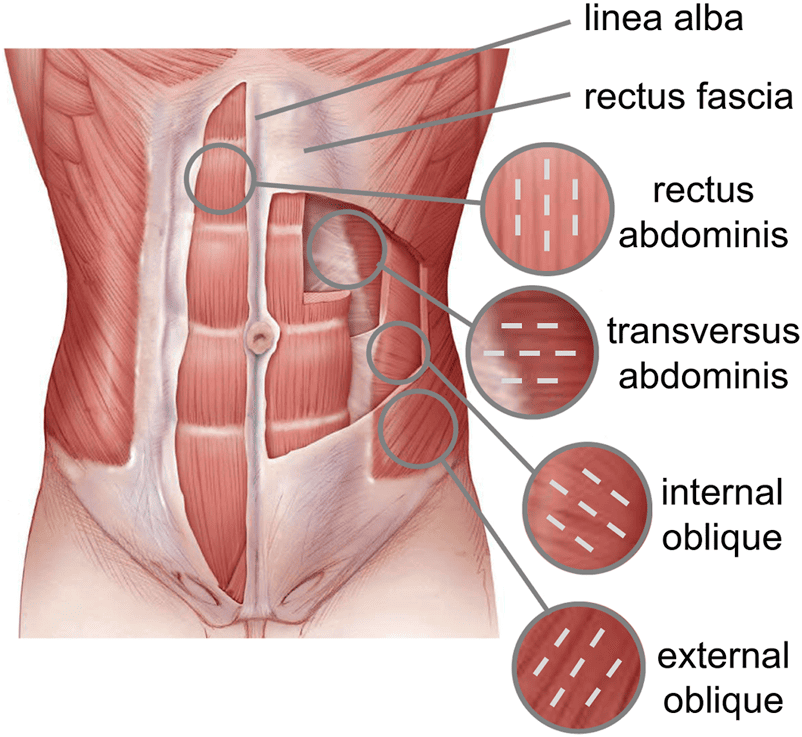

4. Muscles of the Anterior Abdominal Wall:

These muscles provide support, protection, allow movement, and increase intra-abdominal pressure. They are arranged in layers.

External Oblique Muscle

- Location: The most superficial and largest of the three flat muscles. Its fibers run inferomedially (like putting hands in pockets).

- Origin: External surfaces of ribs 5-12.

- Insertion: Linea alba, pubic tubercle, iliac crest.

- Aponeurosis: Forms a strong aponeurosis that contributes to the rectus sheath and forms the inguinal ligament.

Internal Oblique Muscle

- Location: Lies deep to the external oblique. Its fibers run superomedially (perpendicular to external oblique fibers).

- Origin: Thoracolumbar fascia, iliac crest, inguinal ligament.

- Insertion: Costal cartilages of ribs 10-12, linea alba, pubic crest.

- Aponeurosis: Splits to contribute to both anterior and posterior layers of the rectus sheath.

Transversus Abdominis Muscle

- Location: The deepest of the three flat muscles. Its fibers run primarily transversely.

- Origin: Costal cartilages of ribs 7-12, thoracolumbar fascia, iliac crest, inguinal ligament.

- Insertion: Linea alba, pubic crest.

- Function: Compresses abdominal contents, crucial for forced expiration, defecation, and parturition.

Rectus Abdominis Muscle

- Location: A pair of long, vertical muscles running on either side of the linea alba.

- Origin: Pubic symphysis and pubic crest.

- Insertion: Xiphoid process and costal cartilages of ribs 5-7.

- Features: Interrupted by three or more tendinous intersections (lineae transversae). Enclosed within the rectus sheath.

5. Rectus Sheath:

A strong, fibrous compartment enclosing the rectus abdominis muscles (and pyramidalis muscle, if present). It is formed by the aponeuroses of the three flat abdominal muscles (external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis). The composition of the rectus sheath varies above and below the arcuate line (located midway between the umbilicus and the pubic symphysis).

- Above Arcuate Line:

- Anterior Layer: Aponeurosis of external oblique + anterior lamina of internal oblique.

- Posterior Layer: Posterior lamina of internal oblique + aponeurosis of transversus abdominis.

- Below Arcuate Line:

- Anterior Layer: Aponeuroses of all three flat muscles (external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis).

- Posterior Layer: Only the transversalis fascia (the aponeuroses pass anterior to the rectus abdominis).

6. Fascia Transversalis:

- A thin but strong layer of fibrous tissue that lies immediately internal to the transversus abdominis muscle (and its aponeurosis).

- It forms the deepest muscular layer and lines the entire abdominal cavity, deep to the muscles.

- Clinical Significance: It forms the posterior wall of the inguinal canal in its lateral part and gives rise to the internal spermatic fascia of the spermatic cord. It is also a site where direct inguinal hernias can protrude.

7. Extraperitoneal Fat:

- A variable layer of loose connective tissue and fat located between the transversalis fascia and the parietal peritoneum.

- It allows for movement of the peritoneum over the deeper structures and provides cushioning.

8. Parietal Peritoneum:

- The innermost layer, a thin, serous membrane that lines the inner surface of the abdominal wall.

- It is continuous with the visceral peritoneum, which covers the organs, and secretes serous fluid to reduce friction.

- Innervation: The parietal peritoneum is richly innervated by somatic nerves (similar to the overlying abdominal wall), making it sensitive to pain, temperature, touch, and pressure. Inflammation or irritation of the parietal peritoneum (e.g., peritonitis) causes sharp, localized pain.

Skin of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

The skin forms the outermost protective layer of the anterior abdominal wall, playing crucial roles in sensation, thermoregulation, and acting as a barrier against external threats.

Characteristics:

- Thickness: Generally, the skin over the abdomen is relatively thin compared to other areas like the back or palms. This can vary somewhat with age and individual body habitus.

- Hair Distribution: It is typically hairy, especially in males, where the distribution and density of hair can vary from a sparse pattern to a dense, diamond-shaped pattern extending from the pubic region up to the umbilicus and sometimes to the chest. In females, hair is usually sparser and confined to the pubic region.

Lines of Cleavage (Langer's Lines):

- Description: These are tension lines in the skin that correspond to the orientation of collagen fibers within the dermis. On the anterior abdominal wall, these lines generally run almost horizontally.

- Clinical Significance:

- Surgical Incisions: Surgeons are often advised to make incisions parallel to Langer's lines whenever possible.

- Healing: Incisions made along these lines tend to gape less, heal with less tension, and result in finer, less conspicuous (hairline) scars. Incisions perpendicular to these lines tend to pull open more, leading to wider, thicker, and more noticeable scars.

Attachment to Underlying Structures:

- The skin of the anterior abdominal wall is generally loosely attached to the underlying superficial fascia. This loose attachment allows for a degree of mobility, which is important for flexibility and accommodating changes in abdominal girth (e.g., during pregnancy or with weight gain/loss).

- Exception: The Umbilicus: At the umbilicus (navel), the skin is firmly tethered to the deeper structures, specifically to the scar tissue formed by the remnants of the umbilical cord (the obliterated umbilical vessels and urachus). This firm attachment is why the umbilicus remains a fixed point despite changes in abdominal distension.

Nerve and Blood Supply:

The skin of the anterior abdominal wall possesses a rich nerve and blood supply, reflecting its importance in sensation and its metabolic activity.

- Nerve Supply (Sensory):

- Innervated by the thoracoabdominal nerves (anterior primary rami of spinal nerves T7-T11) and the subcostal nerve (anterior primary ramus of T12). These nerves pierce the anterior rectus sheath to become superficial and supply the skin.

- The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves (L1) supply the skin in the inferolateral and inguinal regions.

- This rich sensory innervation makes the abdomen sensitive to touch, pain, temperature, and pressure.

- Dermatomes: Understanding the dermatomal distribution of these nerves is crucial for localizing referred pain or sensory deficits (e.g., the umbilicus is typically at the T10 dermatome level).

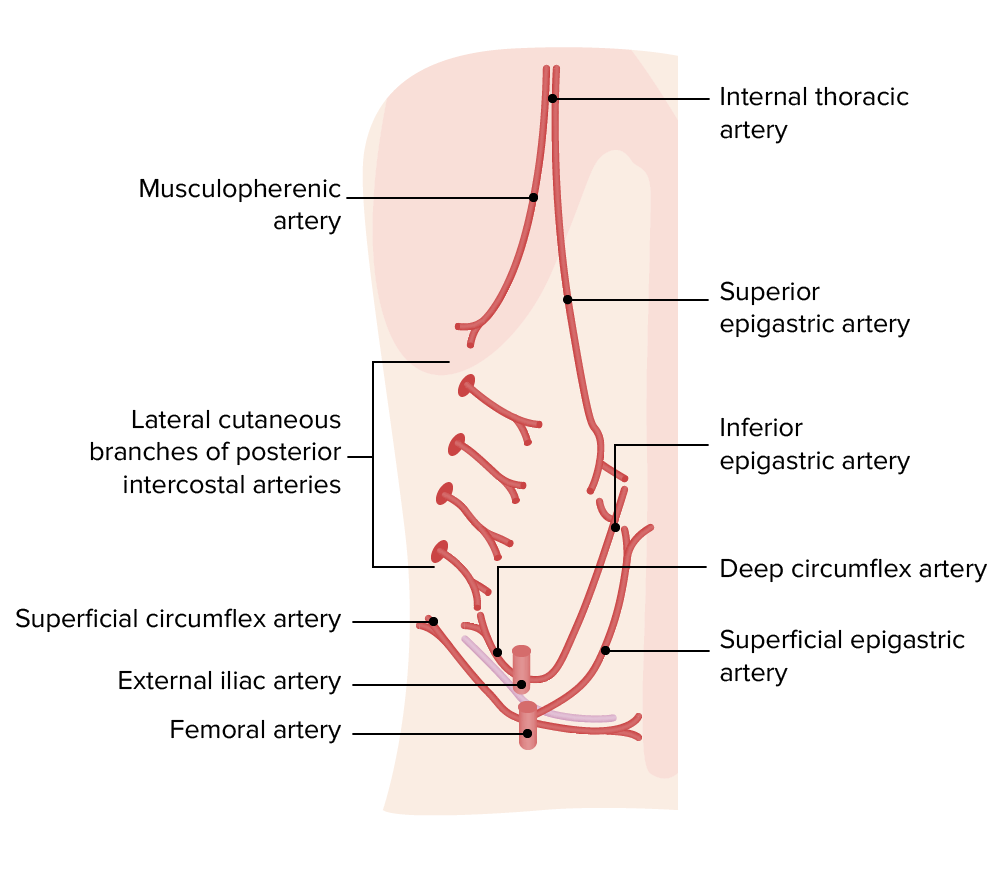

- Blood Supply (Arterial):

- Derived from numerous branches, ensuring excellent vascularization for healing and metabolic needs.

- Superiorly: Branches from the superior epigastric artery (a terminal branch of the internal thoracic artery) and intercostal arteries.

- Laterally: Branches from the segmental lumbar arteries and the circumflex iliac arteries (superficial and deep).

- Inferiorly: Branches from the inferior epigastric artery (a branch of the external iliac artery) and the superficial epigastric artery (a branch of the femoral artery).

- These vessels form extensive anastomotic networks throughout the superficial and deep layers of the abdominal wall.

- Venous Drainage:

- Superiorly: Drains into the superior epigastric veins and subsequently the internal thoracic veins.

- Laterally: Drains into the intercostal veins and lumbar veins.

- Inferiorly: Drains into the inferior epigastric veins (to external iliac vein) and the superficial epigastric veins (to femoral vein).

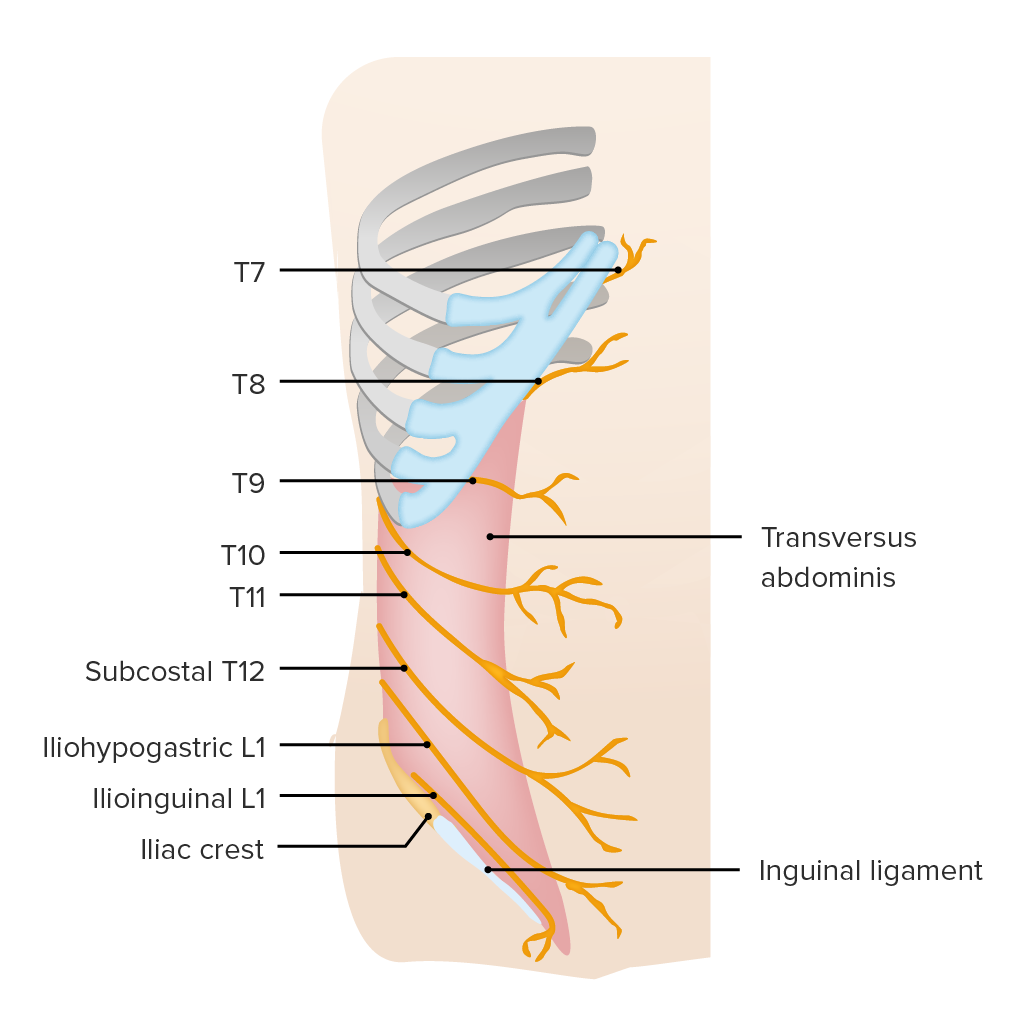

Cutaneous Nerves of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

The skin of the anterior abdominal wall receives its sensory innervation from the ventral rami of the spinal nerves, specifically from segments T7 through L1. These nerves not only provide sensation to the skin but also supply motor innervation to the abdominal muscles.

Path of Nerves:

- After exiting the intervertebral foramina, the ventral rami of T7-L1 typically run anteriorly and laterally.

- They pass inferiorly and medially in the neurovascular plane, which is located between the internal oblique muscle and the transversus abdominis muscle. This anatomical arrangement is crucial for regional anesthesia techniques.

Types of Innervation:

- Motor Innervation: The branches of these nerves supply the abdominal muscles (external oblique, internal oblique, transversus abdominis, and rectus abdominis), enabling their contraction for movements, forced expiration, and maintaining intra-abdominal pressure.

- Cutaneous Innervation: These nerves give off branches that pierce through the muscle and fascial layers to supply the skin:

- Lateral Cutaneous Branches: Emerge in the midaxillary line, supplying the skin over the lateral aspect of the abdominal wall.

- Anterior Cutaneous Branches: Continue anteriorly, penetrating the rectus sheath (and rectus abdominis muscle, if applicable) to supply the skin of the anterior midline.

Specific Nerves and Their Dermatomes:

- Ventral Rami of T7 through T11 (Thoracoabdominal Nerves):

- These are the continuations of the intercostal nerves beyond the costal margin.

- They supply the skin and muscles of the upper and middle parts of the anterior abdominal wall.

- T7 Dermatome: Supplies the skin over the xiphoid process.

- T10 Dermatome: Supplies the skin at the level of the umbilicus. This is a clinically important landmark.

- Subcostal Nerve (Ventral Ramus of T12):

- Runs below the 12th rib and enters the abdominal wall.

- Supplies the skin and muscles in the lower abdominal wall, inferior to T11.

- Ventral Ramus of L1: This spinal nerve segment specifically gives rise to two important nerves for the lower abdominal wall and inguinal region:

- Iliohypogastric Nerve: Supplies sensation to the skin over the anterolateral abdominal wall (superior to the inguinal ligament and pubic region) and motor innervation to the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles.

- Ilioinguinal Nerve: Supplies sensation to the skin over the lower inguinal region, medial thigh, and parts of the external genitalia (scrotum/labia majora), and motor innervation to the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles.

Fascia of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

The fascial layers play critical roles in defining compartments, containing infection/fluid, and providing structural support.

Superficial Fascia:

As mentioned previously, below the umbilicus, it is distinctly divided into two layers.

1. Fatty Layer (Camper's Fascia)

- Description: This is the most superficial layer of the superficial fascia, primarily composed of fat and loose areolar tissue.

- Continuity: It is continuous with the superficial fascia (fatty layer) over the thorax and the thigh.

- Thickness: Its thickness varies greatly, being particularly prominent in obese individuals, where it can be extremely thick, reaching up to 10 cm or more, often forming one or more sagging folds, especially in the lower abdomen.

- Function: Serves as a major site for fat storage in men and women, and provides insulation and cushioning.

2. Membranous Layer (Scarpa's Fascia)

- Description: A deeper, thin, but relatively strong and elastic fibrous membrane.

- Location: Primarily present only in the anterior abdominal wall below the umbilicus. It becomes less distinct superior to the umbilicus.

- Attachments:

- Superiorly: It is loosely attached to the deep fascia superior to the inguinal ligament and becomes indistinguishable from the fatty layer in the flanks.

- Inferiorly: It firmly attaches:

- To the fascia lata (deep fascia of the thigh) approximately 2.5 cm below the inguinal ligament.

- It passes in front of the pubis and forms a tubular sheath around the base of the penis or clitoris.

- It continues into the perineum, surrounding the scrotum or labia majora, where it is known as Colles' fascia.

Deep Fascia:

- Description: A thin layer of tough, fibrous connective tissue that lies immediately superficial to the abdominal muscles.

- Continuity: It is continuous with the deep fascia in the rest of the body.

- Presence: On the anterior abdominal wall, the deep fascia is generally very thin and often fuses intimately with the aponeuroses of the muscles, especially the external oblique. It is not always considered a completely separate, distinct layer from the muscle aponeuroses in this region.

Abdominal Wall Quiz

Systems Anatomy

Enter your details to begin the examination.

🛡️ Privacy Note: Results are for tracking and certification purposes only.

Abdominal Wall Quiz

Systems Anatomy

Preparing questions...

Exam Completed!

See your performance breakdown below.