Teeth, Tongue & Salivary Glands

Teeth

Teeth are specialized, calcified, whitish structures securely anchored in the jaws of many vertebrates, primarily adapted for the mechanical breakdown of food (mastication). Beyond digestion, they play vital roles in speech articulation and facial aesthetics.

Distinctive Properties:

Teeth differ significantly from bone in several key aspects:

- Hardness: They are considerably harder than bone, primarily due to their higher mineral content and the unique structure of enamel and dentin.

- Regeneration: Unlike bone, which can continuously remodel and repair itself, mature teeth (specifically enamel and dentin) have a very limited capacity for self-repair or regeneration.

- Mineral Content: Teeth possess a significantly higher mineral content (mainly hydroxyapatite) than bone, contributing to their superior hardness and durability.

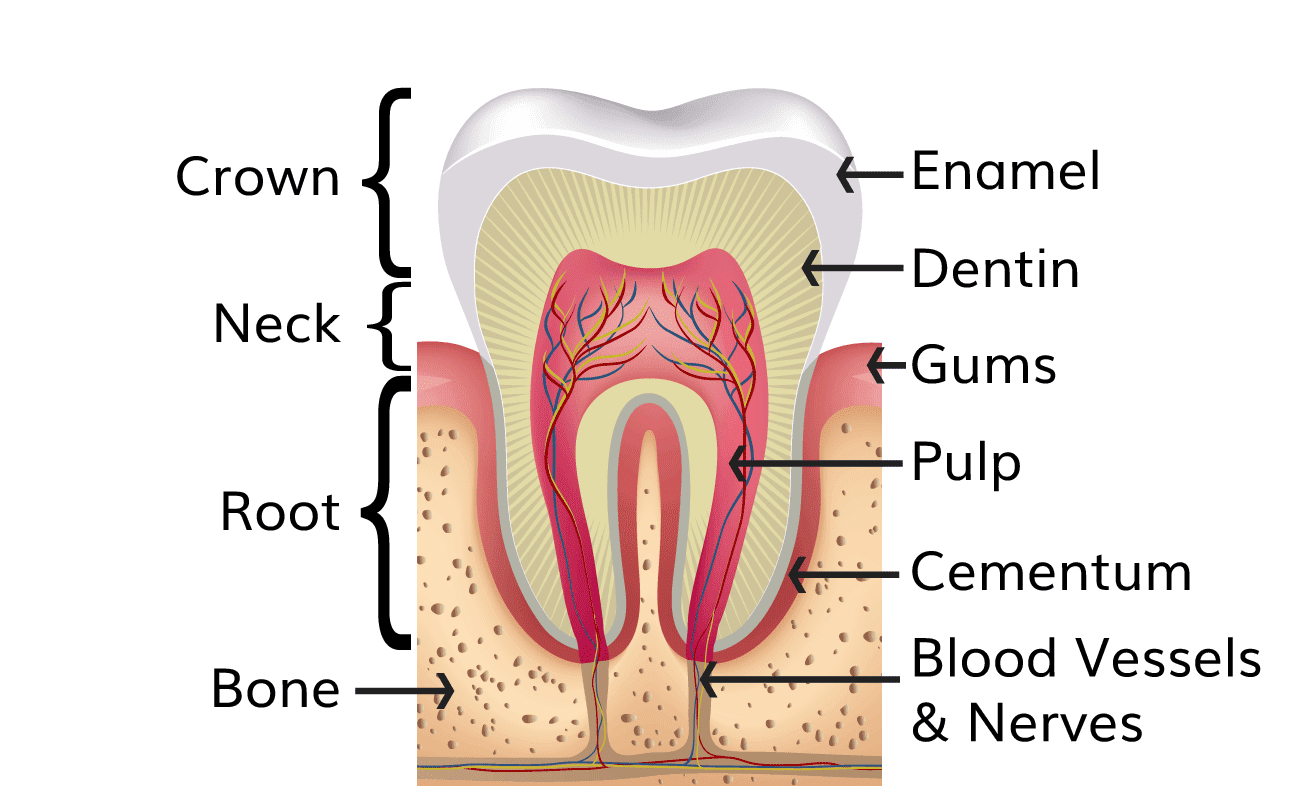

Parts of a Tooth

Each tooth is anatomically divided into three principal parts: the crown, the neck, and the root.

1. The Crown

- Location: This is the visible portion of the tooth that projects into the oral cavity above the gingiva (gum line).

- Protection: It is entirely covered and protected by enamel, the hardest substance in the human body.

- Bulk: The main bulk of the crown is composed of dentin, which lies immediately deep to the enamel.

2. The Neck (Cervix)

- Location: This is the constricted junction where the crown meets the root. It is typically encircled by the gingival margin.

- Covering: At the neck, the enamel of the crown meets the cementum of the root.

3. The Root

- Location: This is the portion of the tooth that is embedded within the alveolar bone of the jaw.

- Attachment: It serves as the anchor for the tooth within its socket.

- Covering: The entire surface of the root is covered by a thin layer of specialized bone-like tissue called cementum. The cementum, in turn, is connected to the alveolar bone of the tooth socket by the periodontal ligament, a fibrous connective tissue that acts as a shock absorber and provides sensory feedback.

Internal Structures of a Tooth:

Beyond the superficial layers, teeth have vital internal components:

- Enamel:

- The outermost layer of the crown, composed of approximately 96% mineral (hydroxyapatite), making it the hardest biological substance.

- It is translucent and provides the protective covering for the crown.

- Formed by ameloblasts during tooth development, which are lost upon eruption, hence its inability to regenerate.

- Dentin:

- Composition: Constitutes the bulk of the tooth, both in the crown and the root. It is a calcified connective tissue, but less mineralized than enamel (around 70% mineral, 20% organic matrix, and 10% water).

- Structure: It contains microscopic channels called dentinal tubules, which radiate outwards from the pulp cavity towards the enamel or cementum. These tubules contain cellular extensions of odontoblasts and dentinal fluid, making dentin somewhat permeable and sensitive.

- Dentinogenesis: The formation of dentin begins prior to enamel formation and is an ongoing process throughout the life of the tooth. It is initiated and maintained by specialized cells called odontoblasts.

- Odontoblasts: The cell bodies of the odontoblasts are aligned along the inner aspect of the dentin, forming the peripheral boundary of the dental pulp. Their processes extend into the dentinal tubules.

- Pulp:

- Location: The innermost cavity of the tooth, centrally located within the dentin.

- Contents: It contains the tooth's living tissues: nerves (providing sensation), blood vessels (providing nutrients), and connective tissue.

- Functions: Provides vitality to the tooth, nourishing the odontoblasts and maintaining the dentin.

Alveolar Ridge and Tooth Sockets:

- Alveolar Ridge: The bony projection of the maxilla and mandible that houses the teeth.

- Alveolus (Tooth Socket): The specific depression or socket within the alveolar ridge where each tooth root is embedded.

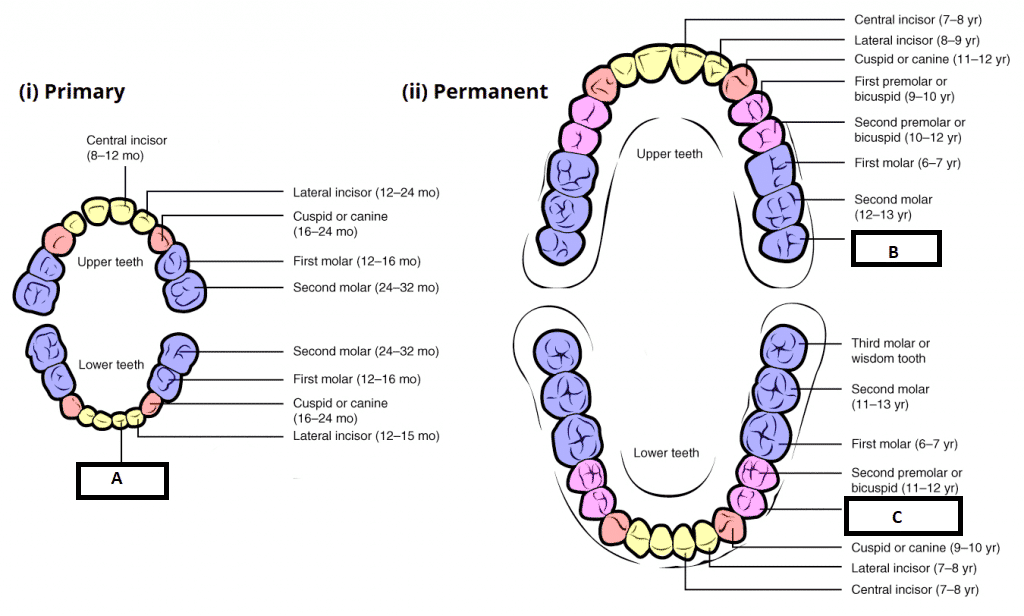

Dentition: Sets of Teeth

Humans are diphyodont, meaning they develop two sets of teeth during their lifetime: deciduous (primary or "milk") teeth and permanent (secondary) teeth.

1. Deciduous Teeth (Primary Dentition):

- Number: There are 20 deciduous teeth in total.

- Distribution per Jaw (Maxilla and Mandible):

- 4 Incisors (2 central, 2 lateral)

- 2 Canines

- 4 Molars (first and second molars)

- Note: Deciduous dentition does not include premolars.

- Eruption: Typically begin to erupt around 6 months after birth. By the end of the second year (approximately 24-30 months), all deciduous teeth have usually erupted.

- Sequence: Generally, the teeth of the lower jaw appear before those of the upper jaw, and incisors erupt first, followed by molars and then canines.

2. Permanent Teeth (Secondary Dentition):

- Number: There are 32 permanent teeth in total.

- Distribution per Jaw (Maxilla and Mandible):

- 4 Incisors (2 central, 2 lateral)

- 2 Canines

- 4 Premolars (first and second premolars)

- 6 Molars (first, second, and third molars)

- Eruption: Begin to erupt around the 6th year of life, replacing the deciduous teeth and adding new molars.

- "Wisdom Teeth" (Third Molars): The third molars are the last teeth to erupt, typically between the ages of 17 to 30 years. They are commonly referred to as "wisdom teeth" due to their late eruption. They often cause problems (impaction, pain) due to insufficient space in the jaws.

Types of Teeth and Their Functions:

Each tooth type is specialized for a particular function:

- Incisors: (Front teeth, 4 per jaw in permanent dentition). Characterized by thin, sharp cutting edges, primarily used for biting and cutting food.

- Canines: (Pointed teeth, 2 per jaw). Possess a single, prominent, conical cusp, designed for tearing food.

- Premolars (Bicuspids): (Behind canines, 4 per jaw in permanent dentition). Each typically has two cusps, used for crushing and grinding food. (Absent in deciduous dentition).

- Molars: (Most posterior teeth, 6 per jaw in permanent dentition). Characterized by three or more broad cusps and a large occlusal (chewing) surface, highly efficient for grinding and pulverizing food.

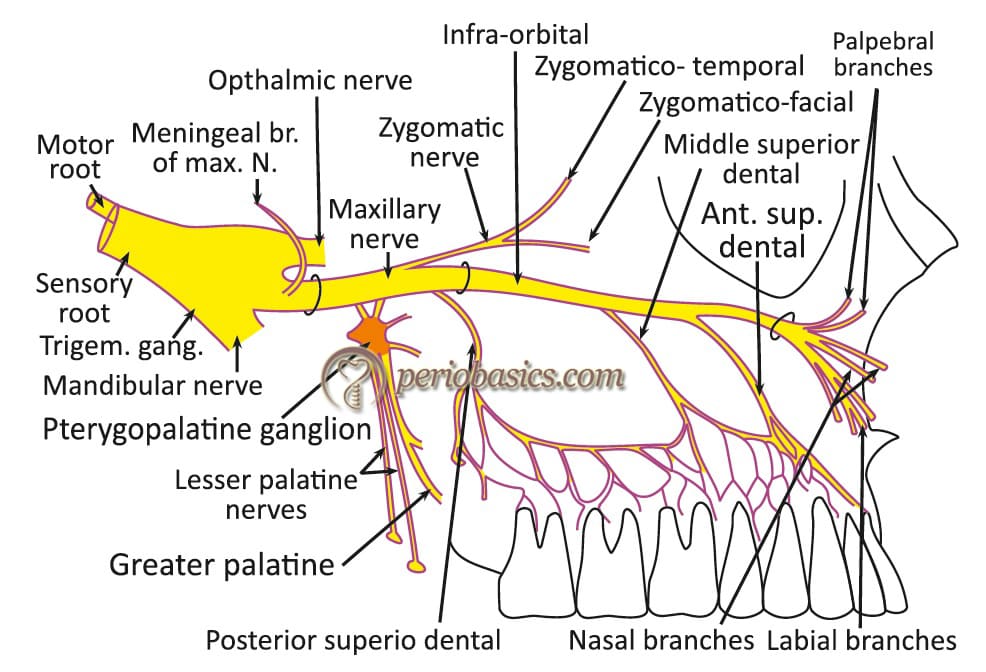

Neurovascular Supply of the Teeth and Gingiva

The teeth and their supporting structures receive a rich blood supply and sensory innervation crucial for their health and function.

Blood Supply:

- Arteries:

- Superior Alveolar Arteries: Branches of the maxillary artery (a terminal branch of the external carotid artery) supply the maxillary (upper) teeth and gingiva. These include the anterior, middle, and posterior superior alveolar arteries.

- Inferior Alveolar Artery: A branch of the maxillary artery that enters the mandibular foramen and runs within the mandible, supplying the mandibular (lower) teeth and gingiva.

- Veins: Veins typically accompany the corresponding arteries (e.g., superior and inferior alveolar veins), eventually draining into the pterygoid venous plexus.

Nerve Supply (Sensory Innervation):

All sensory innervation to the teeth and gingiva is derived from the trigeminal nerve (CN V).

Maxillary Teeth and Gingiva (Upper Jaw)

- Innervated by branches of the maxillary nerve (CN V2):

- Anterior Superior Alveolar Nerve: Supplies the maxillary incisors and canine, and the associated labial gingiva.

- Middle Superior Alveolar Nerve: Supplies the maxillary premolars and the mesiobuccal root of the first molar, and associated buccal gingiva.

- Posterior Superior Alveolar Nerve: Supplies the maxillary molars (except for the mesiobuccal root of the first molar) and associated buccal gingiva.

- These nerves form a network called the superior dental plexus within the alveolar bone.

Mandibular Teeth and Gingiva (Lower Jaw)

- Innervated by branches of the mandibular nerve (CN V3):

- Inferior Alveolar Nerve: Supplies all mandibular teeth. It enters the mandibular foramen and gives off dental branches to the teeth. Its terminal branches include the mental nerve (supplying the lower lip and labial gingiva of anterior teeth) and the incisive nerve (supplying the incisors and canine).

- This nerve forms the inferior dental plexus.

- Lingual Nerve: While not directly supplying teeth, the lingual nerve (a branch of CN V3) provides general sensation to the lingual (tongue-side) gingiva of the mandibular teeth.

- Buccal Nerve: Provides general sensation to the buccal (cheek-side) gingiva of the mandibular molars and premolars.

Lymphatic Drainage: Lymph from the gingiva and teeth primarily drains into the submandibular lymph nodes. Some anterior mandibular gingiva and teeth may drain into the submental lymph nodes.

Caution during surgery: The lingual nerve is closely related to the inner (lingual) aspect of the mandible, particularly in the region of the third molar (wisdom tooth). During surgical procedures involving the removal of impacted mandibular third molars, there is a risk of injury to the lingual nerve, which could result in altered sensation or taste on the ipsilateral side of the tongue.

Disorders of Teeth (Selected Examples)

- Natal Teeth: Teeth that are present at birth. These are often mandibular incisors and can be prematurely erupted deciduous teeth or supernumerary teeth.

- Neonatal Teeth: Teeth that erupt within the first 30 days (first two weeks) after birth.

- Eruption Cysts: A soft tissue cyst that develops over an erupting tooth, appearing as a bluish, fluid-filled swelling on the gingiva. It is a benign condition.

- Microdontia: A condition where one or more teeth are smaller than normal. It can affect a single tooth (e.g., "peg lateral" incisor) or all teeth (generalized microdontia).

- Macrodontia: A condition where one or more teeth are larger than normal.

- Hypodontia: The developmental absence of one or more teeth. Excluding third molars, this is the most common developmental anomaly.

- Supernumerary Teeth (Hyperdontia): The presence of extra teeth in addition to the normal complement. These can occur in various locations and shapes.

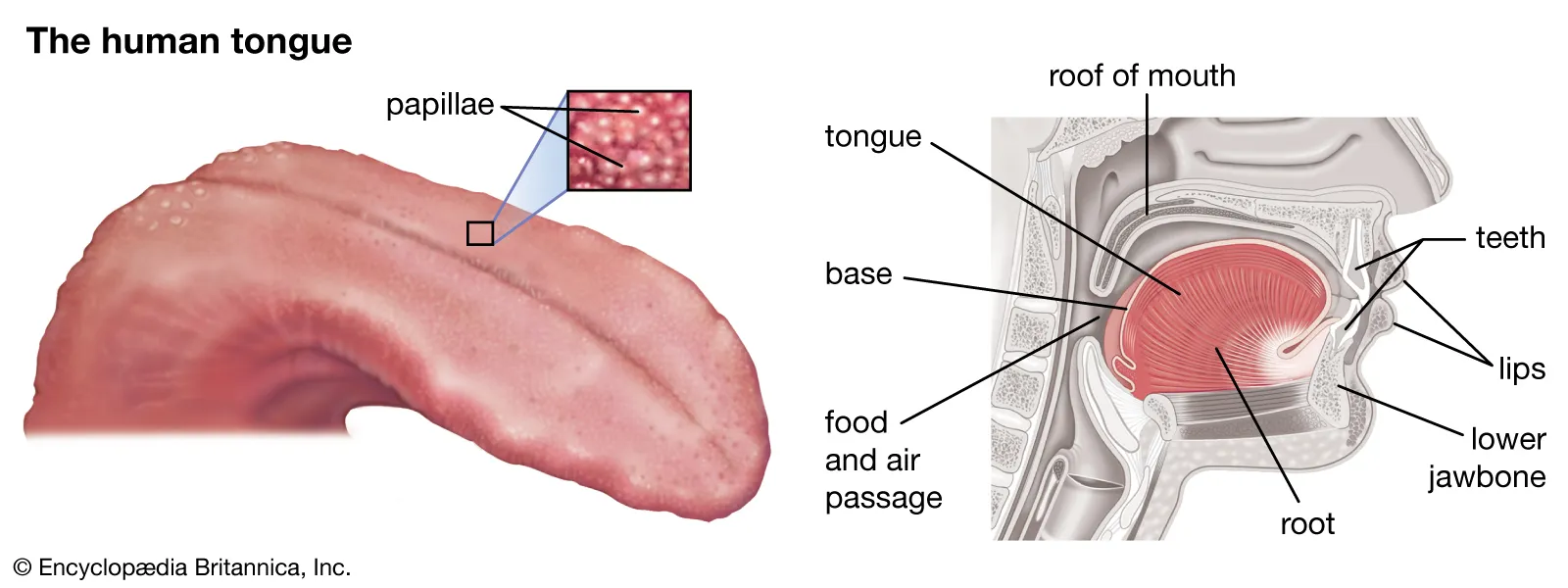

The Tongue

The tongue is a highly mobile, muscular organ located in the oral cavity. It plays crucial roles in mastication, deglutition (swallowing), taste, and speech articulation. It is composed primarily of striated muscle covered by a specialized mucous membrane.

Anatomical Divisions:

- Anterior Two-thirds (Oral Part / Presulcal Part): This portion lies within the oral cavity proper. It is highly mobile and visible when the mouth is open.

- Posterior One-third (Pharyngeal Part / Postsulcal Part): This part forms the anterior wall of the oropharynx. It is fixed to the hyoid bone and largely immobile.

- Root of the Tongue: Refers to the posterior-most part that attaches to the hyoid bone and mandible.

Mucous Membrane of the Tongue:

The tongue's surface is covered by a specialized stratified squamous epithelium. This epithelium is generally non-keratinized in most areas, but the dorsal surface of the anterior two-thirds, particularly in areas of high friction, can exhibit degrees of parakeratinization or even orthokeratinization.

- Division by Sulcus Terminalis: The dorsal surface of the tongue is distinctly divided into the anterior two-thirds and posterior one-third by a prominent, V-shaped groove called the sulcus terminalis.

- The apex of the V points posteriorly towards the pharynx.

- At the apex of the sulcus terminalis lies a small depression, the foramen cecum, which represents the remnant of the proximal opening of the thyroglossal duct (from which the thyroid gland descends during development).

- Lingual Papillae: The dorsal surface of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue is characterized by numerous projections called lingual papillae, which increase the surface area and provide friction. Most types of papillae contain taste buds, specialized sensory organs for taste perception.

1. Filiform Papillae

- Appearance: These are the most numerous and smallest papillae, covering the entire upper surface of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. They appear as thin, long, "V"-shaped (or cone-shaped) projections.

- Function: Primarily mechanical in nature, providing a rough surface for manipulating food. They do not contain taste buds.

- Epithelium: Their epithelium is typically keratinized or parakeratinized, contributing to their mechanical function and whitish appearance.

2. Fungiform Papillae

- Appearance: Less numerous than filiform papillae, these are larger, rounded, and slightly mushroom-shaped (when viewed longitudinally). They often appear reddish due to their highly vascular connective tissue core, which is visible through the thinner overlying epithelium.

- Location: Scattered among the filiform papillae, they are more prevalent at the apex (tip) and sides of the tongue.

- Taste Buds: They contain taste buds on their superior surface.

- Innervation: Taste buds within fungiform papillae are innervated by the chorda tympani nerve, a branch of the facial nerve (CN VII).

3. Vallate (Circumvallate) Papillae

- Appearance: These are the largest papillae, typically 10 to 12 in number, arranged in a single row immediately in front of the sulcus terminalis, forming a V-shape. Each papilla is large and blunt-topped, surrounded by a circular trench or moat.

- Taste Buds: They contain numerous taste buds embedded in the lateral walls of the papillae, facing into the surrounding trench.

- Innervation: Taste buds in the vallate papillae, along with general sensation from this region, are innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX).

4. Foliate Papillae

- Appearance: These are located on the lateral margins of the tongue, particularly posteriorly. They appear as a series of vertical folds or ridges.

- Taste Buds: They contain taste buds, especially prominent in childhood.

- Innervation: Taste buds in foliate papillae are also primarily innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX).

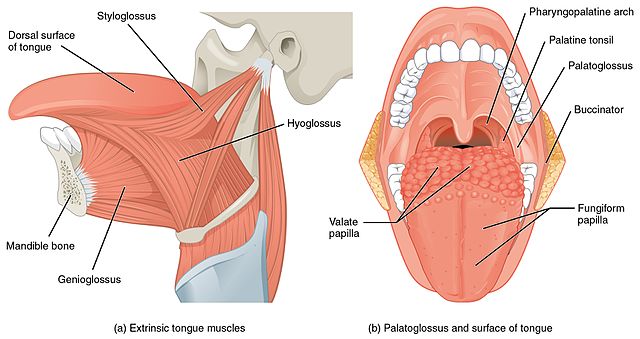

Muscles of the Tongue

The tongue is a muscular hydrostat, meaning it changes shape due to muscle contractions without skeletal support (except at its attachments). Its muscles are divided into two groups:

1. Intrinsic Muscles:

- Attachment: Entirely confined within the tongue itself, not attached to bone.

- Fibers: Composed of three interweaving sets of fibers running in different directions: longitudinal (superior and inferior), transverse, and vertical fibers.

- Action: Primarily responsible for altering the shape of the tongue (e.g., curling, flattening, narrowing, broadening) during speech and chewing.

2. Extrinsic Muscles:

- Attachment: Originate from bone or other structures outside the tongue and insert into the tongue.

- Action: Primarily responsible for altering the position of the tongue (e.g., protrusion, retraction, depression, elevation).

- List of Muscles:

- Genioglossus: Protrudes and depresses the tongue. (Origin: Genial tubercle of mandible)

- Hyoglossus: Depresses and retracts the tongue. (Origin: Hyoid bone)

- Styloglossus: Retracts and elevates the tongue. (Origin: Styloid process of temporal bone)

- Palatoglossus: Elevates the posterior part of the tongue and depresses the soft palate, forming the palatoglossal arch. (Origin: Soft palate)

- All muscles of the tongue, both intrinsic and extrinsic, are supplied by the Hypoglossal Nerve (CN XII), with one significant exception:

- The Palatoglossus muscle is innervated by the Pharyngeal Plexus (derived from branches of the vagus nerve CN X, and glossopharyngeal nerve CN IX). This exception aligns with its origin from the soft palate, which is innervated by the pharyngeal plexus.

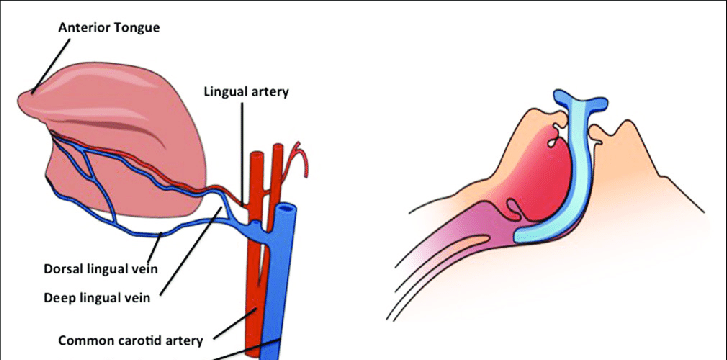

Blood Supply of the Tongue:

The tongue has a rich vascular supply to meet its high metabolic demands.

- Arterial Supply: Primarily by the Lingual Artery, which is a direct branch of the External Carotid Artery. Other contributions include:

- Tonsillar artery: A branch of the facial artery, which supplies the posterior part.

- Ascending pharyngeal artery: A branch of the external carotid artery, which also contributes to the posterior part.

- Venous Drainage: Lingual veins largely follow the arteries. The deep lingual veins eventually drain into the Internal Jugular Vein.

Nerve Supply of the Tongue:

The tongue receives complex innervation for both motor function, general sensation, and special sensation (taste).

- Motor Supply:

- Hypoglossal Nerve (CN XII): Supplies all intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the tongue, except palatoglossus.

- Sensory Supply:

- Anterior Two-thirds (Oral Part):

- General Sensation (touch, pain, temperature): Supplied by the Lingual Nerve, which is a branch of the mandibular nerve (CN V3) of the Trigeminal Nerve (CN V).

- Taste Sensation (except vallate papillae): Supplied by the Chorda Tympani nerve, a branch of the Facial Nerve (CN VII). This nerve joins the lingual nerve in the infratemporal fossa.

- Posterior One-third (Pharyngeal Part) and Vallate Papillae:

- General Sensation AND Taste Sensation (including vallate papillae and foliate papillae): Supplied by the Glossopharyngeal Nerve (CN IX).

- Epiglottis and Extreme Posterior Part of Tongue:

- Some general and taste sensation is also conveyed by the Internal Laryngeal Nerve, a branch of the Vagus Nerve (CN X).

- Anterior Two-thirds (Oral Part):

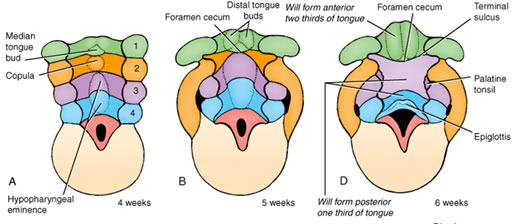

Embryology of the Tongue

The tongue is a composite structure formed by the fusion of several embryonic swellings derived from different pharyngeal arches. This complex origin explains its distinct sensory nerve supply.

- General Principle: The mucous membrane and glands of the tongue are derived from the floor of the pharynx, while the muscles develop separately from occipital somites.

- Development of the Oral Part (Anterior 2/3):

- Derived from mesodermal swellings of the first pharyngeal arch (mandibular arch).

- Specifically, two distal lateral lingual swellings grow from the first arch.

- A triangular midline swelling, the tuberculum impar (meaning "unpaired tubercle" or "shared swelling"), also appears in the floor of the mouth, occupying a groove between the mandibular and hyoid arches.

- The two lateral lingual swellings enlarge rapidly, merge, and overgrow the tuberculum impar to form the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

- Development of the Pharyngeal Part (Posterior 1/3):

- Derived mainly from the third pharyngeal arch.

- Specifically, it forms from a large midline elevation called the copula (or hypobranchial eminence). The copula overgrows the second pharyngeal arch structures.

- The posterior-most part of the tongue, including the epiglottis, develops from the fourth pharyngeal arch.

- Fusion and Foramen Cecum:

- The three main masses (anterior 2/3 from 1st arch and posterior 1/3 from 3rd arch) fuse at the region marked by the foramen cecum, which thus represents the point of fusion between the oral and pharyngeal parts of the tongue. The sulcus terminalis marks the line of this fusion on the surface.

Embryological Basis of Nerve Supply

The different embryological origins precisely explain the disparate sensory nerve supply:

- Anterior 2/3: Derived from the first pharyngeal arch, it receives general sensation from the lingual nerve (branch of CN V3), which is the nerve of the first pharyngeal arch. Taste sensation to this part (except vallate papillae) is from the chorda tympani (CN VII), which is the nerve of the second pharyngeal arch, implying a contribution of the second arch or its nerve to taste buds in this region.

- Posterior 1/3: Derived mainly from the third pharyngeal arch, it receives both general and taste sensation from the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX), which is the nerve of the third pharyngeal arch.

- Epiglottis and extreme posterior: Derived from the fourth pharyngeal arch, it receives sensation from the vagus nerve (CN X), the nerve of the fourth arch.

Tongue Muscles Embryology

The muscles of the tongue (both intrinsic and extrinsic) do not develop from the pharyngeal arches. Instead, they migrate into the developing tongue from occipital somites (myotomes) between 6-8 weeks of gestation, bringing their nerve supply (the Hypoglossal Nerve, CN XII) with them.

- Bifid Tongue (Cleft Tongue / Glossoschisis): A rare condition where the tongue is partially or completely divided, typically at the tip, due to incomplete fusion of the lateral lingual swellings.

- Ankyloglossia (Tongue-Tie): A congenital condition where the lingual frenulum (the band of tissue anchoring the tongue to the floor of the mouth) is unusually short, thick, or tight, restricting the tongue's range of motion. This can interfere with breastfeeding, speech, and oral hygiene.

- Microglossia: A rare condition characterized by an abnormally small tongue.

- Macroglossia: A condition where the tongue is abnormally large. This can be congenital (e.g., associated with certain syndromes like Down syndrome or Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome) or acquired (e.g., due to hypothyroidism, amyloidosis, or tumors).

- Lingual Thyroid: A developmental anomaly where thyroid tissue fails to descend from its embryological origin (foramen cecum) to its normal position in the neck, remaining at the base of the tongue. It can present as a mass on the posterior dorsum of the tongue.

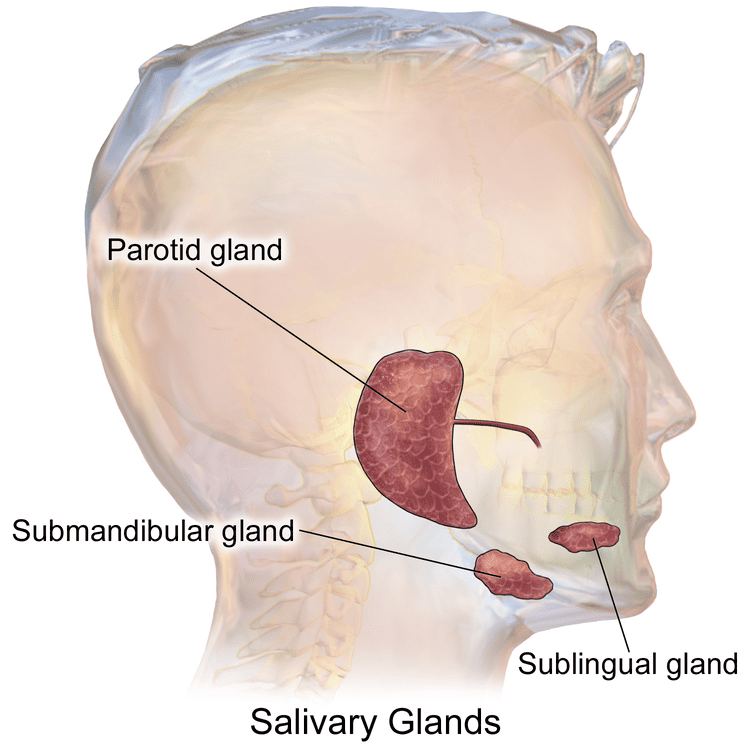

Salivary Glands

The salivary glands are exocrine glands that produce saliva, an essential fluid for maintaining oral health, initiating digestion, and facilitating speech. The major salivary glands consist of three paired glands: the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands.

Functions of Saliva:

- Lubrication: Moistens the oral mucosa, aiding in speech, chewing, swallowing, and protecting against desiccation.

- Digestion: Contains enzymes like salivary amylase (ptyalin), which begins the breakdown of starches (carbohydrates), and lingual lipase (though primarily active in the stomach), which begins lipid digestion.

- Protection: Contains antibodies (e.g., IgA), lysozymes, and other antimicrobial agents that help fight bacteria and maintain oral hygiene. It also helps to neutralize acids, protecting tooth enamel.

- Taste: Acts as a solvent for taste substances, allowing them to stimulate taste buds.

- Cleansing: Helps to wash away food debris from the teeth and oral mucosa.

1. Submandibular Gland (Submaxillary Gland)

The submandibular gland is the second-largest of the major salivary glands. It is a mixed gland, producing both serous and mucous secretions, with serous acini predominating.

Anatomy and Location:

- Location: Situated in the submandibular triangle of the neck, primarily under the body of the mandible.

- Parts: It has a unique configuration with two continuous parts:

- Large Superficial Part: Lies inferior to the mylohyoid muscle.

- Small Deep Part: Wraps around the posterior border of the mylohyoid muscle to lie superior to it, in the floor of the mouth. The two parts are continuous around the free posterior border of the mylohyoid.

- Capsule: Surrounded by a distinct fibrous capsule and ensheathed by the investing layer of the deep cervical fascia.

Histology:

- Classification: It is a branched tubuloacinar gland. The secretory units (adenomeres) are composed of both serous and mucous cells.

- Secretory Units:

- Serous Acini: Predominate, producing a watery fluid rich in enzymes (like salivary amylase).

- Mucous Acini: Produce a viscous, mucin-rich secretion.

- Serous Demilunes: A characteristic feature where serous cells form a crescent (demilune) capping the ends of some mucous acini.

- Duct System: The lobules contain adenomeres that secrete into a system of ducts: intercalated ducts, striated ducts (involved in modifying saliva composition), and excretory ducts.

Relations:

Given its two parts, its relations differ.

- Relations of the Superficial Part:

- Anterior: Anterior belly of the digastric muscle.

- Posterior: Stylohyoid muscle, posterior belly of the digastric muscle, and often abuts the parotid gland.

- Medial: Mylohyoid muscle, hyoglossus muscle. The hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) and lingual nerve (CN V3 branch) pass deep (medial) to this part of the gland.

- Lateral/Inferior: Investing layer of deep cervical fascia, platysma muscle, skin. Submandibular lymph nodes are intimately associated. The cervical branch of the facial nerve (CN VII) typically runs superficial to the gland.

- Relations of the Deep Part:

- Anterior: Sublingual gland.

- Posterior: Styloid process, posterior belly of the digastric muscle, and the parotid gland.

- Medial: Hyoglossus muscle, styloglossus muscle.

- Lateral: Mylohyoid muscle (which separates it from the superficial part).

- Inferior: Hypoglossal nerve (CN XII).

Submandibular Duct (Wharton's Duct)

- Origin: Arises from the anterior end of the deep part of the gland.

- Course: Passes forward along the floor of the mouth, running between the sublingual gland and the genioglossus muscle. It crosses superficial to the lingual nerve.

- Opening: Opens into the oral cavity on a small elevation called the sublingual papilla (caruncula sublingualis), situated at the side of the frenulum of the tongue.

- Palpation: Both the duct and the deep part of the gland can be palpated through the mucous membrane of the floor of the mouth.

Neurovascular Supply and Lymphatic Drainage:

- Blood Supply:

- Arteries: Branches of the facial artery and lingual artery, both branches of the external carotid artery.

- Veins: Drain into the facial vein and lingual vein, which in turn drain into the internal jugular vein.

- Lymphatic Drainage: Primarily into the submandibular lymph nodes and then to the deep cervical lymph nodes.

- Nerve Supply:

- Parasympathetic (Secretomotor): Originates from the superior salivatory nucleus in the brainstem, travels via the chorda tympani nerve (a branch of the facial nerve, CN VII). The chorda tympani joins the lingual nerve (CN V3), and its preganglionic fibers synapse in the submandibular ganglion, which is suspended from the lingual nerve. Postganglionic fibers then supply the submandibular and sublingual glands.

- Sympathetic: Postganglionic fibers originate from the superior cervical ganglion and travel along the plexuses on the facial and lingual arteries to reach the gland. Sympathetic stimulation generally reduces salivary flow and makes it more viscous.

The submandibular gland is the most common site for salivary calculi (stones) due to the longer, tortuous, and upward-sloping course of Wharton's duct against gravity, and the higher mucin content of its saliva. These stones are typically composed of calcium salts and can obstruct the duct, leading to pain, swelling, and infection.

2. Sublingual Gland

The sublingual gland is the smallest and most superficially located of the major salivary glands.

Anatomy and Location:

- Location: Lies in the floor of the mouth, beneath the mucous membrane, anterior to the deep part of the submandibular gland. It forms the sublingual fold (plica sublingualis) on either side of the frenulum linguae.

- Shape: Almond-shaped or horseshoe-shaped.

- Capsule: Lacks a distinct fibrous capsule; instead, it is surrounded by a loose connective tissue capsule.

Histology:

- Classification: It is a mixed gland, but with mucous acini predominating. It is often categorized as a predominantly mucous gland.

- Secretory Units: Contains many mucous acini, often capped with serous demilunes. The overall secretion is more viscous than that of the submandibular gland.

- Duct System: Unlike the other major glands, the sublingual gland does not have a single main duct.

Relations:

- Anterior: Often in contact with the gland of the opposite side.

- Posterior: Deep part of the submandibular gland.

- Medial: Genioglossus muscle, lingual nerve, submandibular duct (which passes medial to the sublingual gland).

- Lateral: Medial surface of the mandible (in the sublingual fossa).

- Superior: Mucous membrane of the floor of the mouth.

- Inferior: Mylohyoid muscle.

Sublingual Ducts (Ducts of Rivinus)

- Number: Numerous small ducts, typically 8-20 in number.

- Opening:

- Most open independently into the oral cavity along the summit of the sublingual fold.

- A few may join the submandibular duct (Wharton's duct) or open directly into it.

- The largest of the sublingual ducts, the Bartholin's duct (major sublingual duct), sometimes opens with Wharton's duct at the sublingual papilla.

Neurovascular Supply and Lymphatic Drainage:

- Blood Supply:

- Arteries: Branches of the facial artery and lingual artery.

- Veins: Drain into the facial vein and lingual vein.

- Lymphatic Drainage: Similar to the submandibular gland, primarily into the submandibular lymph nodes and then to the deep cervical lymph nodes.

- Nerve Supply:

- Parasympathetic (Secretomotor): Identical to the submandibular gland. Preganglionic fibers from the chorda tympani (facial nerve, CN VII) travel with the lingual nerve, synapse in the submandibular ganglion, and postganglionic fibers then supply the sublingual gland.

- Sympathetic: Similar to the submandibular gland, postganglionic fibers from the superior cervical ganglion travel along arterial plexuses.

3. Parotid Gland

- Location: Largest salivary gland, situated inferior and anterior to the external ear, partially superficial to the masseter muscle.

- Duct: Parotid duct (Stensen's duct) pierces the buccinator muscle and opens into the vestibule of the mouth opposite the second maxillary molar tooth.

- Secretion: Primarily serous, producing a watery, enzyme-rich saliva.

- Nerve Supply:

- Parasympathetic: From the inferior salivatory nucleus, via the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX), then the lesser petrosal nerve, synapsing in the otic ganglion. Postganglionic fibers travel with the auriculotemporal nerve (CN V3) to the gland.

- Sympathetic: From the superior cervical ganglion, traveling along the external carotid artery plexus.

- Relations: Intimately related to the facial nerve (CN VII), which passes through the gland but does not innervate it.

| Feature | Parotid Gland | Submandibular Gland | Sublingual Gland |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Largest | Second Largest | Smallest |

| Secretion Type | Purely Serous | Mixed (predominantly serous) | Mixed (predominantly mucous) |

| Main Duct | Stensen's Duct | Wharton's Duct | Multiple small ducts (Rivinus'), some joining Wharton's or Bartholin's |

| Duct Opening | Vestibule, opp. 2nd maxillary molar | Sublingual papilla | Sublingual fold |

| Parasympathetic | Glossopharyngeal (CN IX) -> Otic G. | Chorda Tympani (CN VII) -> Submand. G. | Chorda Tympani (CN VII) -> Submand. G. |

Teeth, Tongue & Salivary Gland Quiz

Systems Anatomy

Enter your details to begin the examination.

🛡️ Privacy Note: Results are for tracking and certification purposes only.

Teeth, Tongue & Salivary Gland Quiz

Systems Anatomy

Preparing questions...

Exam Completed!

See your performance breakdown below.