Oral Cavity / Mouth Cavity

The Oral Cavity/Mouth Cavity

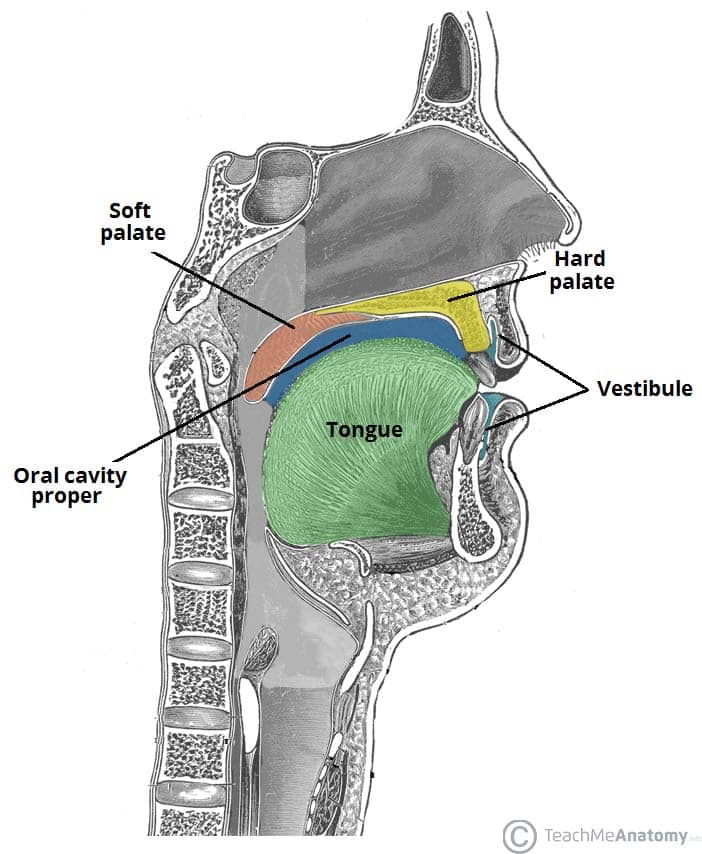

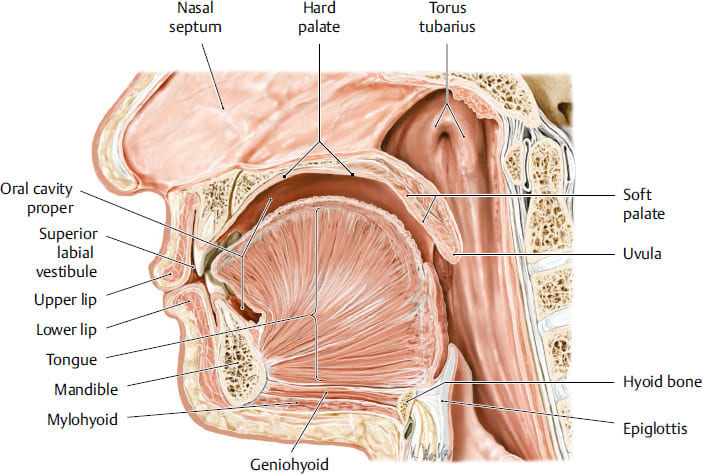

The oral cavity, often simply referred to as the mouth, serves as the initial segment of the digestive system and plays crucial roles in respiration and speech.

- Boundaries: It extends from the external opening, formed by the lips, posteriorly to the oropharyngeal isthmus. The oropharyngeal isthmus represents the critical junction where the oral cavity transitions into the pharynx (throat).

- Primary Divisions: The oral cavity is distinctly divided into two main components:

- The Oral Vestibule

- The Oral Cavity Proper (or Mouth Proper)

The Oral Vestibule

The oral vestibule is a peripheral, slit-like space, serving as the entranceway to the main oral cavity.

- Communication: It directly communicates with the external environment through the oral fissure, which is the opening defined by the lips.

- Defining Boundaries:

- Externally: Its outer limits are established by the mobile structures of the lips (anteriorly) and the cheeks (laterally).

- Internally: Its inner boundary is formed by the fixed structures of the gingivae (gums) and the teeth.

- Lining: The entire vestibule is lined by a specialized mucous membrane. This membrane seamlessly covers the internal surfaces of the lips and cheeks and then reflects (folds back) onto the superior and inferior gingivae and the adjacent teeth.

Detailed Structures of the Vestibule:

A. The Cheeks (Buccae)

The cheeks constitute the primary lateral walls of the oral vestibule and are integral to various oral functions.

- Core Structure: The foundation of each cheek is the buccinator muscle. This muscle is essential for maintaining the shape of the cheek and facilitating mastication.

- Layers:

- External Surface: Covered by the skin of the face and a superficial connective tissue layer known as the buccinator fascia.

- Internal Surface: Lined by the smooth, moist mucous membrane of the oral vestibule.

- Muscular Function: The buccinator muscle is classified as a muscle of facial expression. Its contractions are vital for:

- Pressing the cheeks against the teeth, which prevents food from accumulating in the vestibule during chewing (mastication).

- Aiding in the expulsion of air (e.g., blowing).

- Contributing to facial expressions.

- Innervation: The motor innervation to the buccinator muscle is provided by the buccal branch of the facial nerve (Cranial Nerve VII). (Note: The provided text had "fascial nerve," which is a common typo for "facial nerve.")

B. The Lips (Labia)

The lips are highly mobile, musculofibrous folds that encircle the oral fissure. They are crucial for both oral function and communication.

- Extent and Location:

- Superiorly: They extend to the nasolabial sulci (the grooves running from the sides of the nose to the corners of the mouth) and the base of the nares (nostrils).

- Inferiorly: They are bounded by the mentolabial sulcus (the groove separating the lower lip from the chin).

- Laterally: They merge with the cheeks at the oral commissures (corners of the mouth).

- Composition: The lips are complex structures containing:

- Muscles: Primarily the orbicularis oris muscle, which acts as a sphincter to close the mouth, along with superior and inferior labial muscles that assist in lip movement.

- Connective Tissue: Fibrous tissue providing support and structure.

- Glands: Numerous small labial salivary glands (mucous and serous).

- Vessels and Nerves: An extensive network to supply the rich functions of the lips.

Lip Functions and Control:

- Diverse Functions: The lips perform a wide array of functions:

- Grasping Food: Facilitating the intake of food and fluids.

- Sucking Fluids: Essential for actions like drinking from a straw or nursing.

- Maintaining Oral Seal: Crucially, they keep food and liquids within the oral cavity proper, preventing spillage into the vestibule during chewing and swallowing.

- Speech Articulation: Modulating sounds for clear speech.

- Facial Expression and Communication: Conveying emotions and participating in social interactions (e.g., kissing).

- Control of the Oral Opening: The opening and closing of the mouth, as well as the intricate movements of the lips, are orchestrated by a group of circumoral muscles. These include:

- Orbicularis Oris: The primary sphincter of the mouth.

- Buccinator: Assists in pressing the lips against the teeth.

- Risorius: Draws the corner of the mouth laterally.

- Various depressor muscles (e.g., depressor anguli oris, depressor labii inferioris) that pull the lips downwards.

- Various elevator muscles (e.g., levator anguli oris, levator labii superioris) that pull the lips upwards.

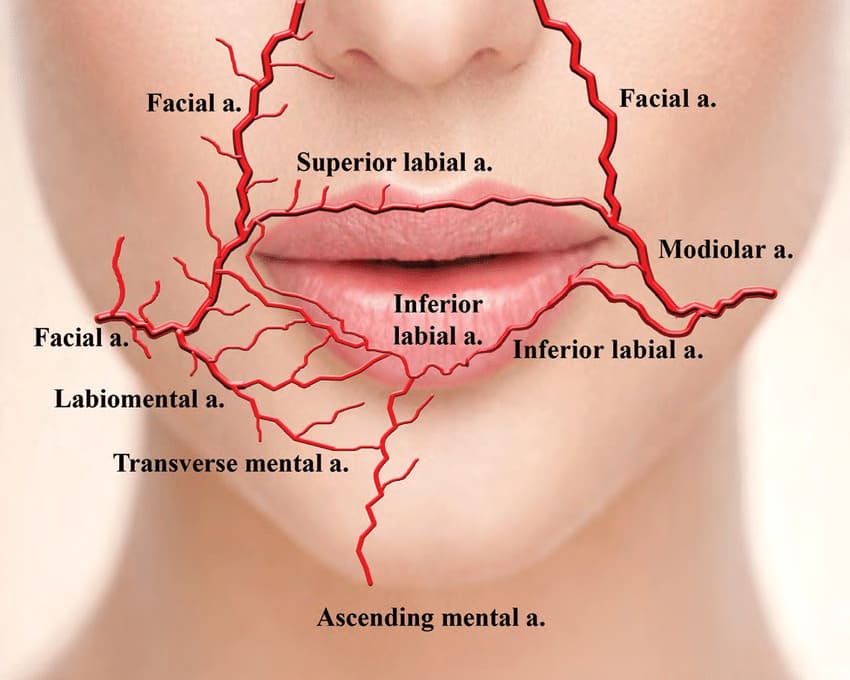

The arterial supply to the lips is highly vascular, arising from branches of the facial artery.

- Upper Lip: Primarily supplied by the superior labial artery (a branch of the facial artery) and contributions from the infraorbital artery (a branch of the maxillary artery).

- Lower Lip: Primarily supplied by the inferior labial artery (a branch of the facial artery) and contributions from the mental artery (a terminal branch of the inferior alveolar artery).

Innervation of the Lips:

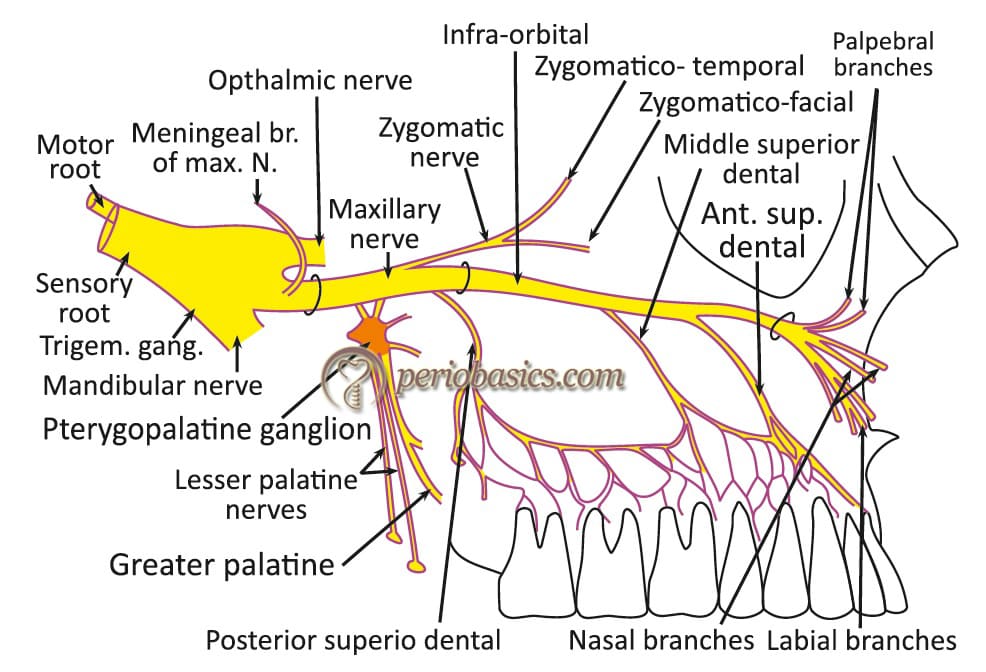

Sensory innervation to the lips is derived from branches of the trigeminal nerve (Cranial Nerve V).

- Upper Lip: Receives sensory innervation from the superior labial branches of the infraorbital nerve. The infraorbital nerve is itself a branch of the maxillary nerve (CN V2).

- Lower Lip: Receives sensory innervation from the inferior labial branches of the mental nerve. The mental nerve is a terminal branch of the inferior alveolar nerve, which stems from the mandibular nerve (CN V3).

Lymphatic Drainage of the Lips:

The lymphatic drainage patterns of the lips are important for understanding the spread of infections or malignancies.

- Upper Lip and Lateral Aspects of the Lower Lip: Lymph from these regions typically drains into the submandibular lymph nodes.

- Medial Part of the Lower Lip: Lymph from this specific area drains into the submental lymph nodes.

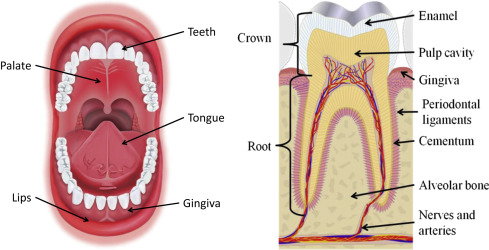

C. The Gingivae (Gums)

The gingivae are the specialized mucous membranes that surround the necks of the teeth and cover the alveolar processes of the jaws.

- Composition: They are composed of dense fibrous tissue richly covered by a specialized mucous membrane.

- Types of Gingiva:

- Gingiva Proper (Attached Gingiva):

- This portion is characteristically firmly attached to the underlying periosteum of the alveolar processes of the jaws and also directly to the cementum at the necks of the teeth.

- Visually, it presents as pink and has a stippled (orange-peel) appearance.

- Histologically, it is typically keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium, which provides protection against mechanical forces during mastication.

- Alveolar Mucosa (Unattached or Mobile Gingiva):

- This is the more loosely attached, thinner, and less keratinized mucous membrane that is continuous with the attached gingiva but does not directly cover the tooth.

- It typically appears shiny red due to its thinner epithelium and rich vascularity, and it is non-keratinizing. Its looser attachment allows for mobility of the cheeks and lips.

- Gingiva Proper (Attached Gingiva):

Nerve Supply of the Gingivae:

The sensory innervation of the gingivae mirrors that of the surrounding alveolar bone and teeth.

- Upper Gingiva (Maxillary Gingiva): Supplied by branches of the infraorbital nerve. These include the anterior, middle, and posterior superior alveolar nerves, which also supply the maxillary teeth and surrounding structures.

- Lower Gingiva (Mandibular Gingiva) and Mucosa of the Floor of the Mouth (Anteriorly): Supplied by branches of the inferior alveolar nerve and its terminal branch, the mental nerve.

- Mucosa over the Cheeks: As mentioned previously, the sensory innervation for the buccal mucosa (inner lining of the cheek) is provided by the buccal branch of the mandibular nerve (CN V3) (distinct from the buccal branch of the facial nerve, which is motor).

The Oral Cavity Proper

The oral cavity proper is the central and largest area of the mouth, positioned internal to the dental arches.

- Location: It is situated directly behind the teeth and gums.

- Defining Boundaries:

- Roof: Formed by the palate.

- The hard palate constitutes the anterior, bony part of the roof.

- The soft palate forms the posterior, muscular part, extending into the oropharyngeal isthmus.

- Floor: Primarily formed by the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. Additionally, the reflections of the mucous membrane from the sides of the tongue onto the gingiva of the mandible contribute to its boundaries.

- Anterolateral Walls: Defined by the gums and teeth of both the maxillary and mandibular arches.

- Posterior Wall: Opens into the oropharyngeal isthmus, which acts as the gateway to the pharynx.

- Roof: Formed by the palate.

Key Features of the Oral Cavity Proper

- Lingual Frenulum: A prominent fold of mucous membrane located in the midline on the floor of the mouth. It connects the undersurface of the tongue to the floor, restricting excessive posterior movement of the tongue.

- Sublingual Papillae (Caruncles): Positioned on each side of the base of the lingual frenulum, these small elevations contain the orifices (openings) of the ducts of the submandibular salivary glands, through which saliva is released.

- Sublingual Fold (Plica Fimbriata): This is a rounded ridge of mucous membrane that runs laterally from the sublingual papilla, beneath the tongue. It is produced by the underlying sublingual salivary gland and contains the numerous small ducts of this gland that open directly into the oral cavity proper.

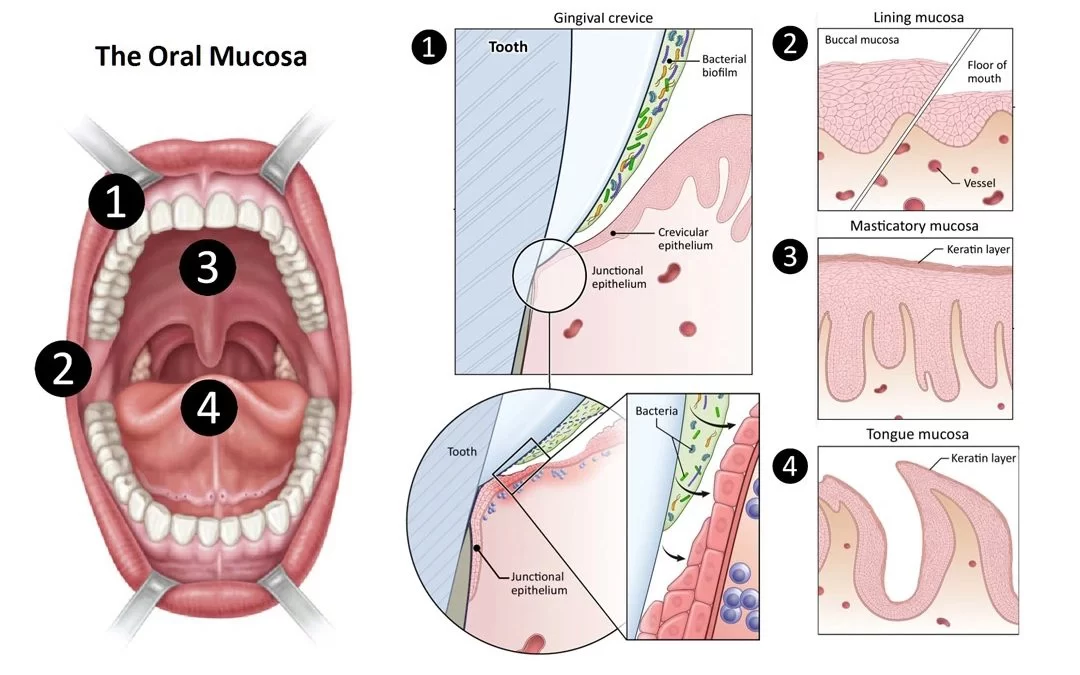

The Oral Mucosa

The entire oral cavity, including both the vestibule and the oral cavity proper, is meticulously lined by a specialized type of mucous membrane known as the oral mucosa. This lining serves a critical protective role and contributes significantly to oral sensation.

- Protective Function: The primary function of the oral mucosa is to act as a barrier, protecting the underlying tissues from mechanical trauma, microbial invasion, and chemical irritants encountered during food intake and other oral activities.

- Sensory Receptors: The oral mucosa is richly endowed with various sensory receptors, allowing for the perception of touch, pressure, pain, and temperature. Notably, the dorsal surface of the tongue contains specialized taste receptors (taste buds), which are crucial for chemical sensation and the perception of taste.

- Epithelial Structure: The epithelium of the oral mucosa is predominantly stratified squamous epithelium. This multi-layered structure provides excellent protection against abrasion.

- Keratinization: The degree of keratinization (presence of a tough, protective layer of keratin) varies depending on the functional demands of the specific region. For instance, the epithelium of the hard palate and the gingiva proper is typically keratinized or parakeratinized due to the significant friction and mechanical forces these areas endure during mastication.

- Non-Keratinization: Areas such as the soft palate, the floor of the mouth, the ventral surface of the tongue, and the alveolar mucosa are generally covered by non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, which is more flexible but less protective.

- Underlying Connective Tissue: The epithelial layer is supported by a robust layer of dense irregular connective tissue called the lamina propria. This lamina propria firmly anchors the epithelium, provides vascular and nervous supply, and contains various cells of the immune system.

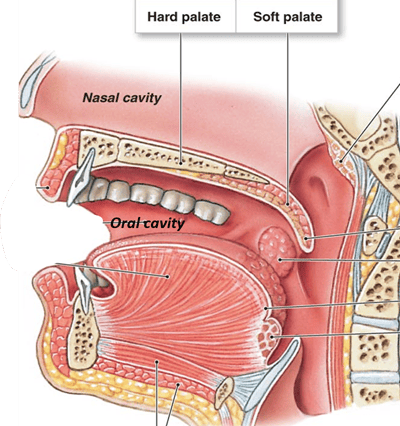

The Palate

The palate forms the arched roof of the oral cavity, effectively separating it from the nasal cavity superiorly. This anatomical separation is vital for both respiration and deglutition (swallowing), allowing for simultaneous breathing and chewing/swallowing.

The palate is functionally and structurally divided into two distinct regions:

- The Hard Palate: The anterior two-thirds, which is bony and rigid.

- The Soft Palate: The posterior one-third, which is fibromuscular and highly mobile.

1. The Hard Palate

The hard palate forms the unyielding anterior portion of the oral cavity's roof.

- Bony Composition:

- Anteriorly: Composed of the palatine processes of the maxillae (premaxilla anteriorly and maxillary palatine process posteriorly).

- Posteriorly: Composed of the horizontal plates of the palatine bones.

- These bones unite at the midline to form the median palatine suture and with the maxillae at the transverse palatine suture.

- Boundaries:

- Anteriorly and Laterally: Bounded by the alveolar processes and the gingivae that house the maxillary teeth.

- Posteriorly: It is continuous with the more mobile soft palate.

- Mucosal Covering: The hard palate is covered by a specialized, thick, keratinized stratified squamous epithelium that is intimately and firmly attached to the underlying periosteum of the palatine bones. This intimate connection makes the mucosa largely immovable, providing a stable surface for tongue manipulation of food.

- Shape and Function: Its surface is typically concave, and at rest, it is largely filled by the tongue. This concavity, along with its rigid nature, is crucial for compressing food against it during mastication and for creating negative pressure during sucking.

- Key Anatomical Features:

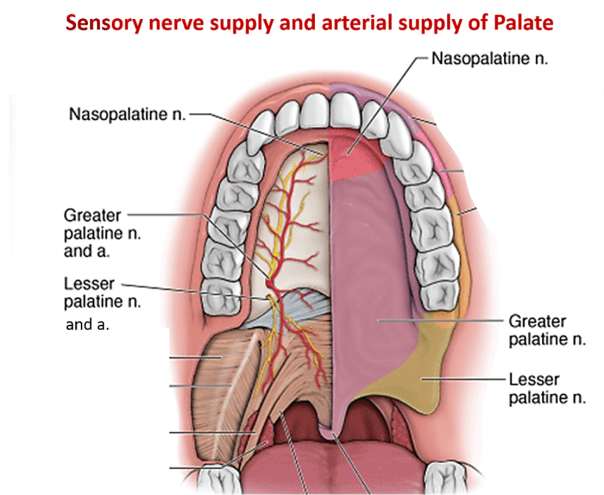

- Incisive Fossa (or Foramen): Located in the midline, posterior to the incisor teeth. This fossa contains the openings of the incisive canals, which transmit the nasopalatine nerves and the terminal branches of the greater palatine arteries from the nasal cavity to the hard palate.

- Greater Palatine Foramen: Situated on the lateral border of the bony palate, medial to the third molar tooth (or between the 2nd and 3rd molars). The greater palatine nerve and greater palatine artery emerge through this foramen to supply the majority of the hard palate.

- Lesser Palatine Foramina: Located posterior to the greater palatine foramen, often in the pyramidal process of the palatine bone. These transmit the lesser palatine nerves and lesser palatine arteries to supply the soft palate and adjacent regions.

- Glandular Component: Deep to the mucosa of the hard palate, particularly in the posterior regions, are numerous mucus-secreting palatine glands. These glands contribute to the lubrication of the oral cavity.

- Sensory Innervation: Primarily by the greater palatine nerve (a branch of the maxillary nerve, CN V2, via the pterygopalatine ganglion) for the posterior two-thirds, and the nasopalatine nerve (also from CN V2, via the pterygopalatine ganglion) for the anterior one-third.

- Arterial Supply: Predominantly from the greater palatine artery (a branch of the maxillary artery), which runs anteriorly from the greater palatine foramen. Contributions also come from the posterior septal branch of the sphenopalatine artery via the incisive canal.

2. The Soft Palate (Velum Palatinum)

The soft palate is the mobile, muscular posterior one-third of the palate, essential for speech, swallowing, and respiration.

- Structure: It is a fibromuscular flap with no underlying bony framework. It is attached to the posterior edge of the hard palate anteriorly.

- Mobility: Its muscular composition allows it to be highly movable and flexible, enabling it to assume various positions during oral functions.

- The Uvula: A conical, fleshy projection of soft tissue that hangs from the posterior free margin of the soft palate in the midline. The musculus uvulae is entirely contained within it.

- Functions:

- Swallowing (Deglutition): During swallowing, the soft palate (and uvula) are reflexively elevated, effectively sealing off the nasopharynx from the oropharynx. This prevents food and liquids from entering the nasal cavity.

- Speech: It plays a crucial role in articulation, especially for non-nasal (oral) sounds, by directing airflow either through the mouth or the nose.

Lateral Attachments and Arches of the Soft Palate:

Laterally, the soft palate is continuous with two arches that connect it to the tongue and the pharynx:

- Palatoglossal Arch (Anterior Arch): This fold of mucous membrane extends from the inferior surface of the soft palate to the lateral aspect of the tongue. It contains the palatoglossus muscle.

- Palatopharyngeal Arch (Posterior Arch): This fold extends from the posterior border of the soft palate to the lateral wall of the pharynx. It contains the palatopharyngeus muscle.

- Palatine Tonsil: Located in the triangular recess (the tonsillar fossa or sinus) situated between the palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal arches. The palatine tonsil is a prominent lymphoid organ, part of Waldeyer's ring, involved in immune surveillance.

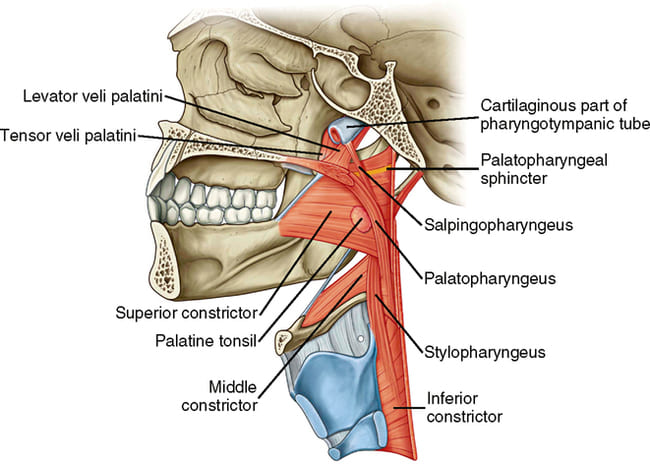

Muscles of the Soft Palate:

Five paired muscles are intricately involved in the movements and functions of the soft palate.

1. Levator Veli Palatini

Action: Primarily elevates the soft palate. It is the main muscle responsible for closing off the nasopharynx during swallowing and speaking. It also helps to open the auditory (Eustachian) tube during swallowing and yawning, thereby equalizing pressure between the middle ear and the pharynx.

Innervation: Supplied by the pharyngeal branch of the vagus nerve (CN X), via the pharyngeal plexus.

2. Tensor Veli Palatini

Action: Tenses the soft palate and also plays a role in opening the mouth of the auditory tube during swallowing and yawning. By tensing the soft palate, it provides a firm base for the levator veli palatini to act upon.

Innervation: Uniquely, it is the only palatine muscle not innervated by the vagus nerve. It is supplied by the nerve to the medial pterygoid muscle, which is a branch of the mandibular nerve (CN V3).

3. Palatoglossus

Action: Forms the palatoglossal arch. Its contraction elevates the posterior part of the tongue and simultaneously depresses the soft palate, effectively narrowing the oropharyngeal isthmus.

Innervation: Supplied by the pharyngeal branch of the vagus nerve (CN X), via the pharyngeal plexus.

4. Palatopharyngeus

Action: Forms the palatopharyngeal arch. It tenses the soft palate and pulls the walls of the pharynx superiorly and medially during swallowing, assisting in closing off the nasopharynx and elevating the pharynx. It also depresses the soft palate.

Innervation: Supplied by the pharyngeal branch of the vagus nerve (CN X), via the pharyngeal plexus.

5. Musculus Uvulae

Action: Shortens and elevates the uvula, pulling it superiorly and anteriorly, which helps to thicken and stiffen the midline of the soft palate to further seal the nasopharynx.

Innervation: Supplied by the pharyngeal branch of the vagus nerve (CN X), via the pharyngeal plexus.

Nerve and Blood Supply of the Soft Palate:

- Sensory Innervation:

- Primarily by the lesser palatine nerves (branches of the maxillary nerve, CN V2, via the pterygopalatine ganglion).

- General sensory and taste fibers are also carried by the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) to the posterior part of the soft palate.

- Arterial Supply:

- Mainly by the lesser palatine artery (a branch of the descending palatine artery, which comes from the maxillary artery).

- Also receives branches from the ascending palatine artery (from the facial artery) and the palatine branch of the ascending pharyngeal artery.

Embryology of the Palate

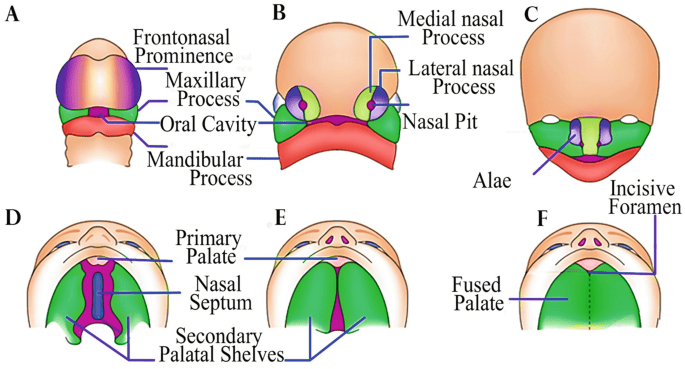

The development of the palate is a complex process crucial for separating the oral cavity from the nasal cavity. This separation is essential for proper feeding, breathing, and speech. The palate develops in two distinct parts: the primary palate and the secondary palate.

1. Primary Palate

- Origin: The primary palate develops from the medial nasal prominences (specifically, the intermaxillary segment), which merge and form a wedge-shaped mass of mesenchyme.

- Location: It forms the small, anterior-most part of the definitive palate, roughly corresponding to the area anterior to the incisive foramen. It contributes to the lip, upper jaw (premaxilla), and the part of the palate bearing the four incisor teeth.

- Timing: Formation occurs early in the 6th-7th week of gestation.

- Significance: It serves as the initial bridge between the developing nasal septum and the oral cavity.

2. Secondary Palate

The secondary palate forms the majority of the hard and soft palate and involves a more intricate process.

- Origin: It develops from two shelflike outgrowths called the palatine processes (or palatal shelves), which emerge from the maxillary prominences of the first pharyngeal arch.

- Initial Growth: At approximately 8 weeks after conception, these two palatine processes begin to grow inwards and downwards on either side of the developing tongue. At this stage, the tongue is relatively large and occupies much of the primitive oral cavity, lying between the palatal shelves.

- Elevation and Reorientation: For successful fusion, the palatine processes must change their orientation. Around the 8th to 9th week, the tongue drops down and flattens, creating space. This allows the vertically oriented palatine processes to rapidly elevate and reorient to a horizontal position above the tongue. This elevation is thought to be mediated by intrinsic forces within the shelves and changes in the head posture.

- Fusion: Once horizontal, the palatine processes grow towards each other and meet in the midline. They then fuse with each other and with:

- The inferior edge of the nasal septum superiorly.

- The posterior margin of the primary palate anteriorly.

- This fusion process begins anteriorly and progresses posteriorly.

- Result of Fusion: This complex series of events effectively divides the primitive oral cavity into three distinct compartments:

- The right nasal cavity.

- The left nasal cavity.

- The definitive oral cavity.

After the initial formation and fusion of the palate, it undergoes further differentiation:

- Hard Palate Formation: The anterior portion of the developing palate is subsequently invaded by bone through intramembranous ossification. This bony development originates from three primary ossification centers that spread to form the hard palate:

- Pre-maxillary center: Contributes to the incisive bone segment (part of the primary palate).

- Maxillary centers: Contributes to the main body of the hard palate from the maxillary processes.

- Palatine centers: Contributes to the posterior horizontal plates of the palatine bones.

- Soft Palate Formation: The posterior portion of the developing palate remains largely fibromuscular and forms the soft palate. The muscles that constitute the soft palate have diverse embryological origins, which explains the variations in their innervation:

- Tensor Veli Palatini: This muscle originates from the mesoderm of the first pharyngeal (mandibular) arch. Consequently, it is innervated by a branch of the mandibular nerve (CN V3), which is the nerve of the first pharyngeal arch.

- All Other Soft Palate Muscles (Levator Veli Palatini, Palatoglossus, Palatopharyngeus, Musculus Uvulae): These muscles originate from the mesoderm of the third and fourth pharyngeal arches. Accordingly, they are innervated by the pharyngeal plexus, which receives contributions from the vagus nerve (CN X) and glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX), nerves associated with the third and fourth arches.

Embryological Origins and Nerve Supply Correlation:

The distinct embryological origins of different palatal structures provide a clear explanation for their varied nerve supplies:

- Primary Palate: Formed from the frontonasal process, its derivatives (like the anterior palate) tend to receive sensory innervation from the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (CN V1), though the primary palate itself is typically associated with the maxillary division for its most anterior part. (The note provided was slightly ambiguous, so I've clarified based on standard embryology).

- Secondary Palate (Maxillary Process Derivatives): Structures derived from the maxillary processes (e.g., the majority of the hard palate) receive sensory innervation from the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve (CN V2) (e.g., greater and lesser palatine nerves).

- Muscles of the Soft Palate: As detailed above, the origin from different pharyngeal arches dictates their motor innervation from CN V3 (for tensor veli palatini) or CN IX/X (for other muscles).

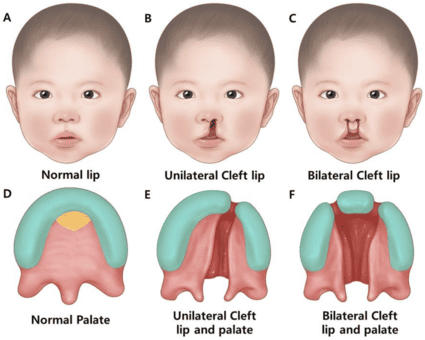

Cleft Lip and Palate

Cleft lip and cleft palate are among the most common congenital craniofacial anomalies, resulting from incomplete fusion of embryonic facial processes. They can lead to significant functional and aesthetic challenges, including difficulties with feeding, speech, hearing, and dental development.

- The Incisive Foramen as a Landmark: In clinical classification, the incisive foramen (the opening in the hard palate behind the central incisors) serves as a critical dividing landmark between anterior and posterior cleft deformities. This reflects the embryological distinction between the primary and secondary palates.

Types of Cleft Deformities:

- Anterior Clefts:

- These involve structures anterior to the incisive foramen.

- They result from a failure of the maxillary prominence to fuse with the medial nasal prominence (which forms the intermaxillary segment, giving rise to the primary palate).

- Examples include:

- Lateral cleft lip: Unilateral or bilateral, where the lip fails to fuse.

- Cleft upper jaw: Involving the alveolar ridge.

- Cleft between the primary and secondary palates: A gap extending through the incisive foramen.

- These are often associated with abnormalities of the primary palate.

- Posterior Clefts:

- These involve structures posterior to the incisive foramen.

- They result from a failure of the palatine shelves (derived from the maxillary prominences) to fuse with each other and/or with the nasal septum.

- Examples include:

- Cleft (secondary) palate: A variable-sized opening in the hard and/or soft palate.

- Cleft uvula: The mildest form, where the uvula is bifid or split.

- These are associated with abnormalities of the secondary palate.

- Combined Clefts:

- This third category involves a combination of both anterior and posterior clefts, often presenting as a continuous cleft extending from the lip, through the alveolar process, and back through the hard and soft palate. This indicates a more extensive failure of fusion processes involving both primary and secondary palates.

Etiology of Cleft Palate:

Cleft palate specifically results from the lack of fusion of the palatine shelves (secondary palate). This failure can be attributed to several factors:

- Smallness of the shelves: The palatine processes may simply be too small to meet in the midline.

- Failure of the shelves to elevate: The shelves may grow normally but fail to reorient from a vertical to a horizontal position above the tongue.

- Inhibition of the fusion process itself: Even if the shelves meet, intrinsic cellular or molecular factors may prevent proper fusion.

- Failure of the tongue to drop: If the tongue remains positioned between the palatine shelves during the critical period of elevation, it can physically obstruct their fusion. This can sometimes occur due to micrognathia (an abnormally small lower jaw), which prevents the tongue from moving forward and downward.

Etiology of Clefts (General):

Most cases of cleft lip and/or cleft palate are considered multifactorial, meaning they arise from a complex interaction of genetic predispositions and environmental factors.

| Feature | Cleft Lip (with or without cleft palate) | Isolated Cleft Palate (without cleft lip) |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence | Approximately 1 in 1000 births. | Much lower, approximately 1 in 2500 births. |

| Sex Predilection | Occurs more frequently in males (approximately 80%). | Occurs more often in females (approximately 67%). |

| Maternal Age | Incidence slightly increases with advancing maternal age. | Not strongly related to maternal age. |

| Population Variation | Significant variability among ethnic populations. | - |

| Recurrence Risk (Genetic) |

|

|

Sex Difference Explanation: A notable embryological difference is that in females, the palatal shelves fuse approximately 1 week later than in males. This delayed fusion period in females might expose them to environmental insults for a longer duration, potentially explaining why isolated cleft palate occurs more frequently in females.

Environmental Factors: Certain environmental exposures are known to increase the risk of cleft palate. For example, anticonvulsant drugs (such as phenobarbital and diphenylhydantoin, also known as phenytoin) taken during pregnancy have been linked to an increased risk of cleft palate. Other factors can include maternal smoking, alcohol consumption, nutritional deficiencies (e.g., folic acid), and certain infections.

https://doctorsrevisionuganda.com | Whatsapp: 0726113908

Oral Cavity Quiz

Systems Anatomy

Enter your details to begin the examination.

🛡️ Privacy Note: Results are for tracking and certification purposes only.

Oral Cavity Quiz

Systems Anatomy

Preparing questions...

Exam Completed!

See your performance breakdown below.