Heart & Great Vessels

The Heart, Pericardium, and Great Vessels

Pericardium

The pericardium is a tough, double-layered fibroserous sac that encloses the heart and the roots of the great vessels (aorta, pulmonary trunk, venae cavae, pulmonary veins).

Main Functions

- Lubrication: Contains a small amount of fluid that reduces friction between the moving heart and the surrounding structures.

- Restriction of Movement: Anchors the heart in the mediastinum, preventing excessive movement and overdistention during sudden increases in blood volume.

- Protection: Acts as a physical barrier against infection and external trauma.

Components

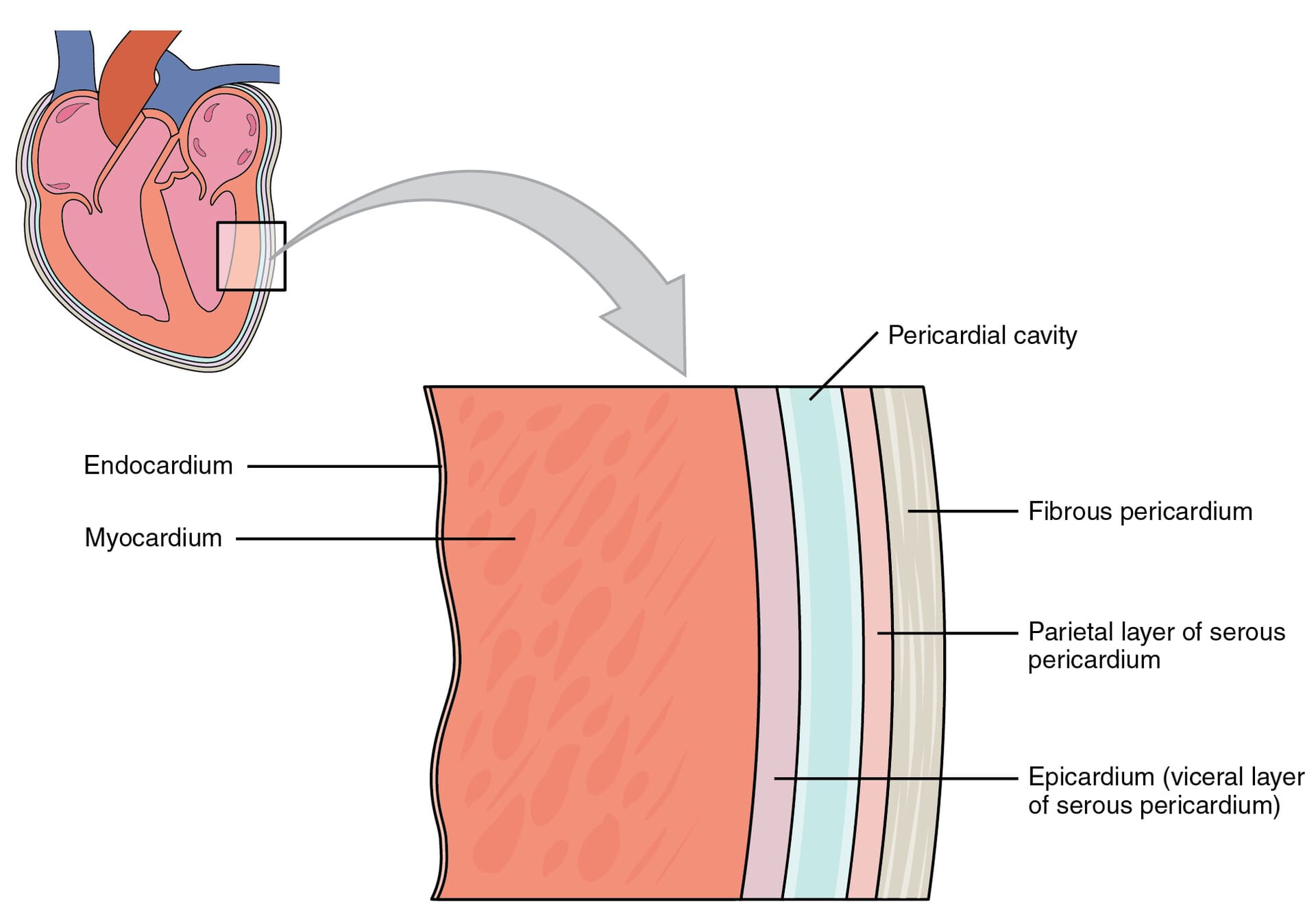

The pericardium is composed of two main layers:

- Fibrous Pericardium (Outer layer)

- Serous Pericardium (Inner layer)

1. Fibrous Pericardium

The fibrous pericardium is the robust, outermost layer of the pericardial sac.

- Description: It is a thick, tough, inelastic, and conical-shaped fibrous bag that surrounds the heart.

- Attachments:

- Inferiorly (Base): It is firmly and broadly fused to the central tendon of the diaphragm. This attachment is crucial for the diaphragm's role in cardiac stability.

- Anteriorly: It is loosely attached to the posterior surface of the sternum by the sternopericardial ligaments.

- Superiorly (Apex): It blends and is fused with the outer connective tissue coats (adventitia) of the great vessels as they enter and leave the heart (aorta, pulmonary trunk, superior vena cava, inferior vena cava, pulmonary veins).

- Posteriorly: It is attached to the structures in the posterior mediastinum, like the esophagus and aorta.

- Embryological Origin: Its primary origin is debated, but contributions are thought to come from the septum transversum (which also gives rise to the central tendon of the diaphragm) and pleuropericardial membranes.

2. Serous Pericardium

The serous pericardium is a thin, delicate, two-layered membrane that lines the inner surface of the fibrous pericardium and covers the external surface of the heart.

- Layers: It is divided into two continuous layers:

- Parietal Layer of Serous Pericardium: This layer lines the inner surface of the fibrous pericardium.

- Visceral Layer of Serous Pericardium (Epicardium): This layer tightly adheres to the outer surface of the heart itself. It is considered the outermost layer of the heart wall.

- Pericardial Cavity: The potential space located between the parietal and visceral layers of the serous pericardium. This space normally contains a small amount of serous fluid.

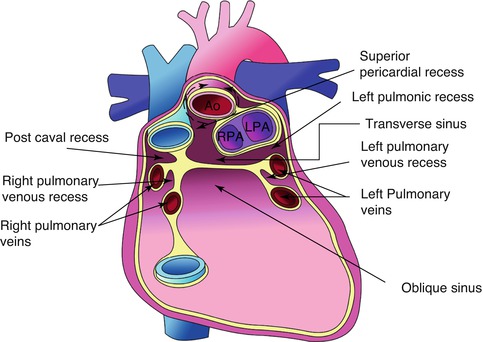

Pericardial Cavity and Sinuses

A. Pericardial Cavity

- Description: A potential space located between the parietal and visceral layers of the serous pericardium.

- Contents: Normally contains a small amount (typically 15-50 mL) of thin, straw-colored serous fluid.

- Function of Fluid: The pericardial fluid acts as a lubricant, allowing the heart to beat smoothly and with minimal friction within the pericardial sac.

- Clinical Significance:

a. Pericardial Effusion: An abnormal accumulation of fluid in the pericardial cavity. This can be caused by various conditions, including infections (e.g., tuberculosis), inflammation (e.g., pericarditis), autoimmune diseases, trauma, and malignancies (tumors). The term "water in the heart" is a colloquial and somewhat misleading description; it's fluid around the heart.

b. Cardiac Tamponade: A life-threatening condition where a large or rapidly accumulating pericardial effusion compresses the heart, restricting its ability to fill adequately with blood during diastole. This leads to reduced cardiac output and can be fatal if not treated promptly.

c. Pericardiocentesis: A medical procedure to aspirate (remove) excess fluid from the pericardial cavity to relieve pressure in cases of pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade.

B. Pericardial Sinuses

These are reflections of the serous pericardium that create cul-de-sacs or recesses.

- Oblique Pericardial Sinus:

- Location: A blind-ended, inverted U-shaped cul-de-sac located posterior to the heart's left atrium.

- Boundaries: It is situated between the reflections of the serous pericardium around the four pulmonary veins and the inferior vena cava (IVC). The posterior wall of the left atrium forms its anterior boundary.

- Clinical Significance: Allows for surgical access to the posterior surface of the heart.

- Transverse Pericardial Sinus:

- Location: A short, transverse tunnel or passage that runs between the great arteries (aorta and pulmonary trunk) anteriorly and the great veins (superior vena cava, inferior vena cava, and pulmonary veins) posteriorly.

- Clinical Significance: This sinus is strategically important for cardiac surgeons. A surgical clamp can be passed through the transverse sinus to temporarily occlude the aorta and pulmonary trunk during cardiac surgery (e.g., for coronary artery bypass grafting or valve replacement), isolating the heart from the systemic circulation.

Innervation and Blood Supply of Pericardium

A. Blood Supply of the Pericardium

The pericardium receives its arterial supply from several sources:

- Pericardiacophrenic Artery: The main arterial supply, a branch of the internal thoracic artery. It accompanies the phrenic nerve.

- Musculophrenic Artery: Another branch of the internal thoracic artery.

- Branches of the Thoracic Aorta: Small branches directly from the aorta (e.g., bronchial and esophageal arteries).

- Coronary Arteries: The visceral layer (epicardium) receives some small branches from the coronary arteries.

- Venous Drainage: Follows the arterial supply, draining into corresponding veins (e.g., pericardiacophrenic veins, internal thoracic veins, azygos system).

B. Innervation of the Pericardium

The innervation differs for the fibrous/parietal serous layers and the visceral serous layer.

- Fibrous Pericardium and Parietal Layer of Serous Pericardium:

- Innervation: Primarily supplied by the phrenic nerves (C3, C4, C5).

- Sensitivity: These layers are richly innervated and are sensitive to pain, temperature, pressure (touch), and stretch.

- Referred Pain: Because the phrenic nerves also supply sensory innervation to the C3-C5 dermatomes, pain originating from these pericardial layers is often referred to the ipsilateral (same side) shoulder, neck, and supraclavicular region. (The original mention of "left jaw" is less common for pericardial pain referral than the shoulder and neck).

- Visceral Layer of Serous Pericardium (Epicardium):

- Innervation: Supplied by the autonomic nervous system (sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers) from the cardiac plexuses.

- Sensitivity: This layer is generally considered insensitive to pain, temperature, and touch. It is primarily sensitive to stretch.

- Function: Autonomic innervation primarily modulates cardiac function rather than providing somatic sensation from the epicardium itself.

The Heart

The heart is a hollow, muscular organ that acts as a pump, circulating blood throughout the entire body to deliver oxygen and nutrients and remove waste products.

- Shape: It is often described as conical or roughly pyramidal in shape, with an apex (pointing infero-anteriorly) and a base (directed postero-superiorly).

- Location: It is situated in the middle mediastinum, slightly to the left of the midline, resting on the diaphragm.

- Mobility:

- The base of the heart (where the great vessels enter and leave) is relatively fixed by its attachment to the great vessels.

- The ventricles (and apex), however, are more mobile within the pericardial sac, allowing for the pumping action.

- The position of the heart changes subtly with respiration and with the cardiac cycle (systole and diastole).

Surfaces of the Heart

The heart has several anatomical surfaces that are important for understanding its relations to surrounding structures and for clinical examination.

- Anterior (Sternocostal) Surface:

- Description: This surface faces anteriorly towards the sternum and costal cartilages.

- Components: Primarily formed by the right ventricle (largest part), a portion of the right atrium, and a small strip of the left ventricle (along the left border).

- Grooves: The anterior interventricular groove (containing the anterior interventricular artery/LAD) and the right atrioventricular (coronary) groove (containing the right coronary artery, often embedded in fat) are visible on this surface.

- Posterior Surface (Base):

- Description: This surface is directed posteriorly, superiorly, and slightly to the right. It is generally the fixed part of the heart.

- Components: Primarily formed by the left atrium, with a smaller contribution from the right atrium.

- Vessels: The four pulmonary veins enter the left atrium on this surface. The superior vena cava enters the right atrium on this surface.

- Important Note: The base of the heart is where the great vessels attach and is relatively fixed, but it does not rest on the diaphragm. The diaphragmatic surface rests on the diaphragm.

- Inferior (Diaphragmatic) Surface:

- Description: This surface rests directly on the central tendon of the diaphragm.

- Components: Primarily formed by the left ventricle (approximately 2/3) and the right ventricle (approximately 1/3). A small portion of the right atrium where the inferior vena cava (IVC) enters is also part of this surface.

- Grooves: The posterior interventricular groove and parts of the coronary groove are found here.

- Apex:

- Description: The blunt, inferolateral tip of the heart.

- Component: Formed entirely by the left ventricle.

- Location (Clinical): Typically located in the left 5th intercostal space, approximately 9 cm (3.5 inches) from the midsternal line (just medial to the midclavicular line). This is where the apex beat (point of maximal impulse) can be palpated.

Borders of the Heart

The heart has distinct borders when viewed from an anterior perspective, which are useful for radiographic interpretation and understanding its anatomical relationships.

- Right Border:

- Components: Formed exclusively by the right atrium.

- Course: Extends from the superior vena cava to the inferior vena cava.

- Left Border:

- Components: Formed primarily by the left ventricle, with a small contribution superiorly from the left auricle (a part of the left atrium).

- Course: Extends from the left auricle to the apex.

- Inferior Border:

- Components: Formed mainly by the right ventricle, a small part of the left ventricle near the apex, and a small part of the right atrium near the IVC entrance.

- Course: Extends from the inferior vena cava to the apex.

- Superior Border:

- Components: Formed by the great vessels entering and leaving the heart (aorta, pulmonary trunk, superior vena cava). It is somewhat obscured by these vessels.

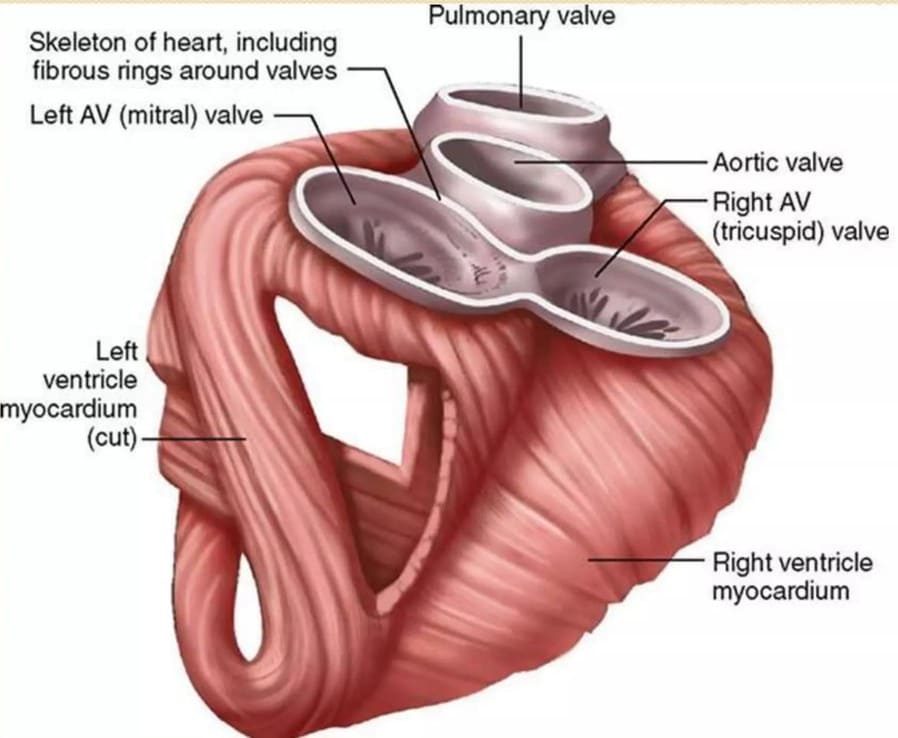

Skeleton of the Heart

The fibrous skeleton of the heart is a crucial structural and functional component, despite being largely fibrous (not bony, except in some animals).

- Description: It is a complex framework of dense connective tissue (fibrous rings) that surrounds the atrioventricular and arterial orifices. It's often described as being in the shape of a figure-8 or two interlocking rings.

- Components: Primarily composed of:

- Annuli Fibrosi: Four fibrous rings that encircle the:

- Right atrioventricular orifice (tricuspid valve).

- Left atrioventricular orifice (mitral valve).

- Aortic orifice.

- Pulmonary orifice.

- Trigonum Fibrosum: Two fibrous trigones (right and left) that connect the fibrous rings.

- Membranous Part of the Interventricular and Interatrial Septa: The fibrous skeleton contributes to these septa.

- Annuli Fibrosi: Four fibrous rings that encircle the:

- Functions:

- Structural Support: Provides a rigid framework for the attachment of the heart valves, maintaining their shape and preventing their overstretching and becoming incompetent (leaky).

- Muscle Attachment: Serves as the origin and insertion for the cardiac muscle fibers of the atria and ventricles.

- Electrical Isolation: Crucially, it forms an electrical barrier between the atria and the ventricles. This electrical discontinuity ensures that the electrical impulses from the atria are only conducted to the ventricles via the atrioventricular (AV) bundle, allowing the atria to contract first, followed by the ventricles in a coordinated sequence.

- Os Cordis: In some animals (e.g., cattle), a small bone called the "os cordis" can be found within the fibrous skeleton, serving similar functions. It is not present in humans.

Walls of the Heart

The wall of the heart is composed of three distinct layers, from superficial to deep:

- Epicardium:

- Description: This is the outermost layer of the heart wall.

- Composition: It is synonymous with the visceral layer of the serous pericardium. It consists of a mesothelium and underlying connective tissue, often containing fat, coronary arteries, and veins.

- Myocardium:

- Description: This is the middle and thickest layer, forming the bulk of the heart wall.

- Composition: It is composed of specialized cardiac muscle tissue. The thickness of the myocardium varies between the different chambers, being thickest in the left ventricle due to its high-pressure pumping demands.

- Endocardium:

- Description: This is the innermost layer that lines the heart chambers and covers the heart valves.

- Composition: It consists of a single layer of flattened epithelial cells called endothelium, supported by a thin layer of connective tissue. It is continuous with the endothelium of the blood vessels entering and leaving the heart.

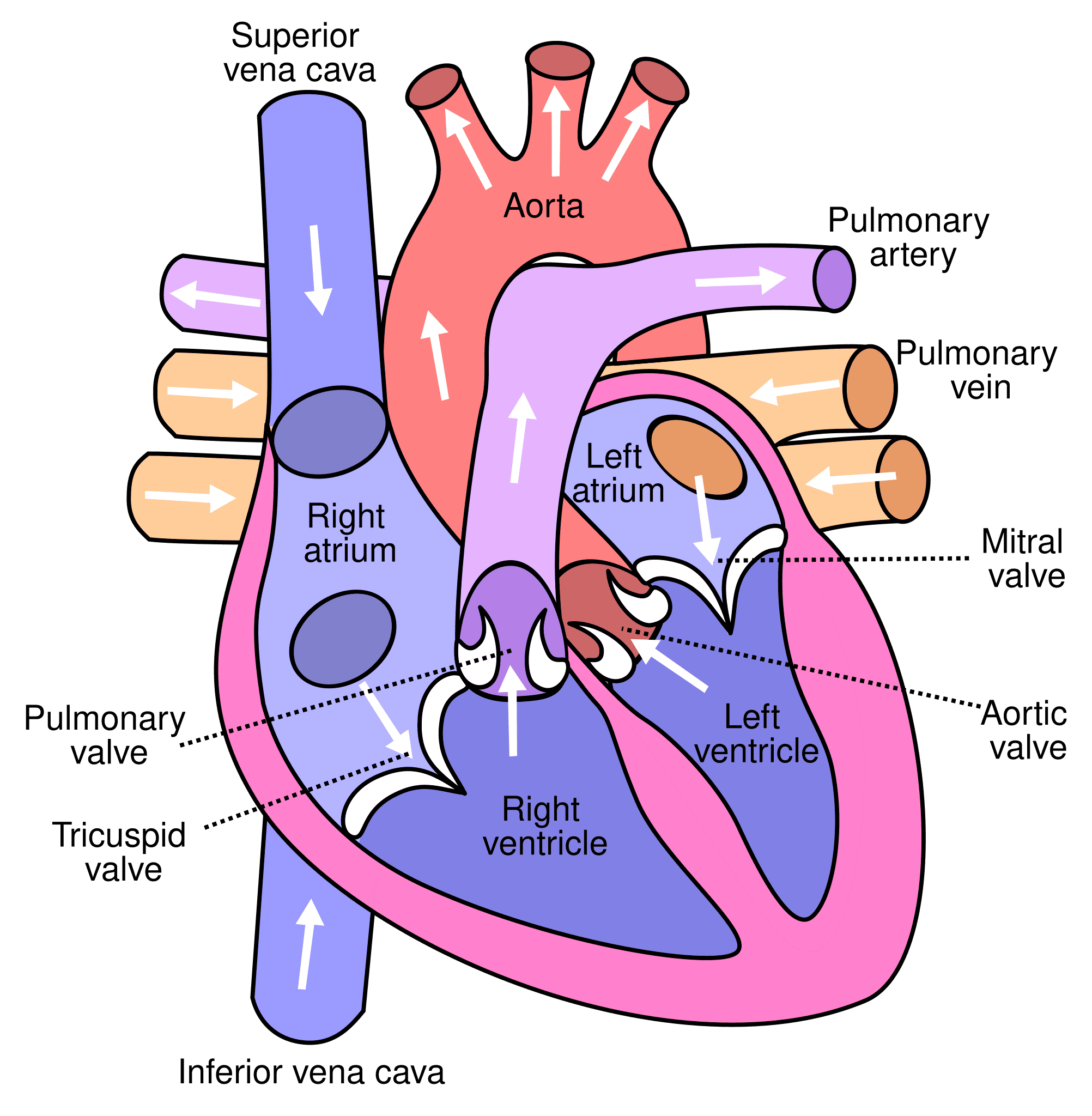

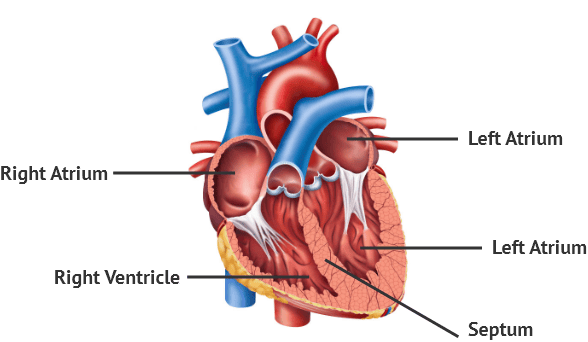

Chambers of the Heart

The human heart is a four-chambered organ, divided into two atria and two ventricles, which work in a coordinated fashion to pump blood.

- Right Atrium (RA): Receives deoxygenated blood from the body.

- Right Ventricle (RV): Pumps deoxygenated blood to the lungs.

- Left Atrium (LA): Receives oxygenated blood from the lungs.

- Left Ventricle (LV): Pumps oxygenated blood to the rest of the body.

1. Right Atrium

The right atrium (RA) is the right upper chamber of the heart, forming its right border.

- Receives Blood From: It collects deoxygenated blood from three main sources:

- Superior Vena Cava (SVC): Drains blood from the head, neck, and upper limbs.

- Inferior Vena Cava (IVC): Drains blood from the trunk, lower limbs, and abdominal viscera.

- Coronary Sinus: The main vein that collects deoxygenated blood from the walls of the heart itself.

- Pumps Blood To: From the right atrium, blood passes through the right atrioventricular (tricuspid) orifice into the right ventricle.

- Structure:

- Main Cavity: The main, larger portion of the atrium.

- Right Auricle: A small, ear-shaped muscular pouch that projects anteriorly from the main atrial cavity.

- Internal Features (Embryological Significance):

- Sulcus Terminalis (External): A shallow groove on the external surface of the right atrium, running between the SVC and IVC.

- Crista Terminalis (Internal): An internal muscular ridge that corresponds to the sulcus terminalis. It divides the right atrium into two embryologically distinct parts:

- Smooth-Walled Part (Sinus Venarum): The posterior, smooth part of the right atrium (posterior to the crista terminalis) is derived from the embryonic sinus venosus (specifically, its right horn). This is where the SVC, IVC, and coronary sinus open.

- Rough-Walled Part: The anterior part (anterior to the crista terminalis), including the right auricle, has prominent muscular ridges called musculi pectinati (pectinate muscles). This part is derived from the embryonic primitive atrium.

Openings and Remnants in the Right Atrium

A. Openings in the Right Atrium:

- Opening of Superior Vena Cava (SVC):

- Location: In the upper, posterior part of the right atrium.

- Valve: No valve guards the SVC opening.

- Opening of Inferior Vena Cava (IVC):

- Location: In the lower, posterior part of the right atrium.

- Valve: Possesses a rudimentary (non-functional in adults) valve, the valve of the IVC (Eustachian valve). In fetal life, this valve directed oxygenated blood from the IVC through the foramen ovale into the left atrium.

- Opening of Coronary Sinus:

- Location: Situated between the opening of the IVC and the right atrioventricular orifice, near the septal cusp of the tricuspid valve.

- Function: Returns most of the deoxygenated blood from the heart wall (myocardium) to the right atrium.

- Valve: Also guarded by a rudimentary (non-functional in adults) valve, the valve of the coronary sinus (Thebesian valve).

- Right Atrioventricular (Tricuspid) Orifice:

- Location: The large opening between the right atrium and the right ventricle.

- Valve: Guarded by the tricuspid valve, a functional valve with three cusps (leaflets):

- i. Anterior cusp.

- ii. Posterior (or inferior) cusp.

- iii. Septal cusp.

- Note: The posterior/inferior cusp is often the smallest.

B. Remnants in the Right Atrium (on the Interatrial Septum):

These structures are important remnants of fetal circulation.

- Fossa Ovalis:

- Description: A shallow, oval depression located on the interatrial septum (the wall separating the right and left atria), on the posterior wall of the right atrium.

- Represents: It is the remnant of the foramen ovale, an opening in the fetal heart that allowed oxygenated blood to bypass the lungs and flow directly from the right atrium to the left atrium.

- Annulus Ovalis (Limbus Fossa Ovalis):

- Description: A prominent, crescent-shaped ridge that forms the superior and anterior margin of the fossa ovalis.

- Formation: It is formed from the lower edge of the embryonic septum secundum, which covered the foramen ovale during fetal development.

2. Right Ventricle

The right ventricle (RV) is the right lower chamber of the heart, situated anteriorly and forming most of the anterior (sternocostal) surface of the heart.

- Receives Blood From: Receives deoxygenated blood from the right atrium through the right atrioventricular (tricuspid) orifice.

- Pumps Blood To: Pumps this deoxygenated blood to the lungs via the pulmonary trunk (pulmonary artery).

- Internal Features:

- Inflow Part: The main part of the right ventricle, receiving blood from the right atrium. Its internal surface is characterized by prominent muscular ridges.

- Outflow Part (Infundibulum / Conus Arteriosus): As the cavity of the right ventricle approaches the pulmonary trunk, it becomes a smooth-walled, funnel-shaped outflow tract called the infundibulum or conus arteriosus. This smooth walls allow for efficient blood ejection into the pulmonary trunk.

- Trabeculae Carneae: Unlike the right atrium which has both smooth and rough parts, the internal surface of the right ventricle (except for the infundibulum) is lined by irregular muscular ridges called trabeculae carneae. These are generally described as three types:

- i. Papillary Muscles: Conical muscular projections that arise from the ventricular wall. Their apices are connected to the free margins and ventricular surfaces of the tricuspid valve cusps by thin, fibrous cords called chordae tendineae. There are typically three papillary muscles: anterior, posterior, and septal. They contract just before ventricular systole to prevent the valve cusps from prolapsing into the right atrium.

- ii. Moderator Band (Septomarginal Trabecula): A distinct, often prominent, muscular band that extends from the inferior part of the interventricular septum to the base of the anterior papillary muscle. It is important because it transmits a part of the right bundle branch of the cardiac conducting system, facilitating efficient conduction to the anterior papillary muscle and the ventricular wall.

- iii. Prominent Ridges: Irregular, raised muscular ridges that crisscross the ventricular wall.

Pulmonary Valve

The pulmonary valve is one of the two semilunar valves of the heart, regulating blood flow from the right ventricle into the pulmonary trunk.

- Location: Guards the pulmonary orifice, the opening between the right ventricle and the pulmonary trunk.

- Composition: It is composed of three semilunar cusps (leaflets), which are delicate, pocket-like structures without chordae tendineae or papillary muscles.

- Attachment: The curved, lower (proximal) margins of the cusps are attached to the fibrous ring surrounding the pulmonary orifice and to the arterial wall of the pulmonary trunk.

- Direction of Opening: The cusps are concave towards the pulmonary trunk. During ventricular systole, they are pushed open, and their "upper mouths" (free edges) are directed into the pulmonary trunk, allowing blood to flow out. During ventricular diastole, blood in the pulmonary trunk tries to flow back into the ventricle, filling the cusps and forcing them closed.

- Arrangement of Cusps: The three cusps are typically named based on their embryonic position (though slight variations exist in anatomical texts):

- Anterior cusp.

- Right cusp.

- Left cusp. (Note: The original "one posterior (left cusp) and two anterior (anterior and right)" is a common descriptive but slightly conflicting categorization. Standard anatomical texts usually list anterior, right, and left for the pulmonary valve.)

- Relative Position: The pulmonary orifice is indeed located slightly superior and to the left of the aortic orifice, although the aortic valve is generally considered to be positioned more centrally in the fibrous skeleton.

3. Left Atrium

The left atrium (LA) is the left upper chamber of the heart.

- Location: It is located posterior to the right atrium, and forms the bulk of the base of the heart.

- Relations:

- Posteriorly: It is closely related to the oblique pericardial sinus and the esophagus. This close relationship means that enlargement of the left atrium (e.g., in mitral valve disease) can compress the esophagus, and can sometimes be visualized in diagnostic imaging like a barium swallow (where barium outlines the esophagus).

- Structure:

- Main Cavity: The main, larger portion of the atrium.

- Left Auricle: A small, ear-shaped muscular pouch that projects anteriorly and superiorly.

- Receives Blood From: It receives oxygenated blood from the lungs via the four pulmonary veins (typically two from the right lung and two from the left lung). These veins enter the posterior wall of the left atrium.

- (Correction: The original text incorrectly states "enclosed in a common sleeve of serous pericardium together with the IVC and the SVC." While the pulmonary veins are covered by a sleeve of serous pericardium, the IVC and SVC are associated with the right atrium, not directly with the left atrium's pulmonary veins in a common sleeve).

- Internal Features (Embryological Significance):

- Smooth Walled: Unlike the right atrium, the majority of the internal surface of the left atrium is smooth-walled. This smooth part is embryologically derived from the incorporation of the pulmonary veins into the primitive left atrium.

- Rough-Walled Auricle: Only the left auricle typically has prominent muscular ridges, the musculi pectinati, derived from the primitive atrium.

Openings in the Left Atrium

The left atrium has two main types of openings:

- Openings of the Four Pulmonary Veins:

- Number: Typically four openings (two superior and two inferior) on the posterior wall of the left atrium.

- Valves: These openings are not guarded by valves. Instead, the oblique course of these veins through the atrial wall and the contraction of the left atrium create a functional sphincter-like action that helps prevent significant backflow of blood during atrial systole.

- Left Atrioventricular (Mitral) Orifice:

- Location: The opening between the left atrium and the left ventricle.

- Valve: Guarded by the bicuspid valve, more commonly known as the mitral valve. It is a functional valve with two cusps (leaflets):

- i. Anterior cusp.

- ii. Posterior cusp.

- Cusp Characteristics: The cusps of the mitral valve are generally thicker and more robust than those of the tricuspid valve, reflecting the higher pressure in the left side of the heart. The anterior cusp is typically larger, thicker, and more rigid than the posterior cusp, and is sometimes referred to as the septal cusp due to its proximity to the interventricular septum.

4. Left Ventricle

The left ventricle (LV) is the left lower chamber of the heart, forming the apex of the heart and a significant portion of its left and diaphragmatic surfaces.

- Receives Blood From: Receives oxygenated blood from the left atrium through the left atrioventricular (mitral) orifice.

- Pumps Blood To: Pumps this oxygenated blood to the entire body via the aorta (specifically, the ascending aorta).

- Wall Thickness and Pressure: The left ventricular wall is significantly thicker (approximately 3 times thicker) than the right ventricular wall. This reflects its role in pumping blood against much higher systemic resistance, resulting in systolic pressures that are typically 5-6 times higher than in the right ventricle.

- Internal Features:

- Trabeculae Carneae: Similar to the right ventricle, the internal surface of the left ventricle is characterized by prominent trabeculae carneae (muscular ridges).

- Papillary Muscles: It possesses two large papillary muscles (anterior and posterior) that connect to the mitral valve cusps via chordae tendineae.

- No Moderator Band: The left ventricle does not have a moderator band; the conduction system (left bundle branch) has a different branching pattern.

- Aortic Vestibule: The smooth-walled outflow tract leading from the main ventricular cavity to the aortic orifice is called the aortic vestibule. This smooth wall ensures efficient blood ejection into the aorta.

- Cross-sectional Shape: In cross-section, the left ventricle is typically described as circular or oval-shaped, while the right ventricle is more crescentic, wrapping around the left ventricle. (The original "triangular" for LV cross-section is not standard; it's typically circular/oval due to the high pressure).

Openings in the Left Ventricle

The left ventricle has two crucial openings:

- Left Atrioventricular (Mitral) Orifice:

- This opening, as discussed earlier, leads from the left atrium into the left ventricle and is guarded by the mitral valve.

- Aortic Opening (Aortic Orifice):

- Location: Leads from the left ventricle into the ascending aorta.

- Relative Position: It is located posterior and to the right of the pulmonary orifice, and slightly inferior to it.

- Valve: Guarded by the aortic valve, which is composed of three semilunar cusps:

- i. Right coronary cusp.

- ii. Left coronary cusp.

- iii. Posterior (non-coronary) cusp.

- Arrangement and Function: These cusps have a similar semilunar arrangement and function to the pulmonary valve, preventing backflow of blood into the left ventricle during diastole.

- Aortic Sinuses (Sinuses of Valsalva): Just above the aortic cusps are three dilatations in the wall of the ascending aorta called the aortic sinuses. These are crucial:

- i. The right coronary artery originates from the right aortic sinus (corresponding to the right coronary cusp).

- ii. The left coronary artery originates from the left aortic sinus (corresponding to the left coronary cusp).

- iii. The posterior (non-coronary) sinus does not give rise to a coronary artery.

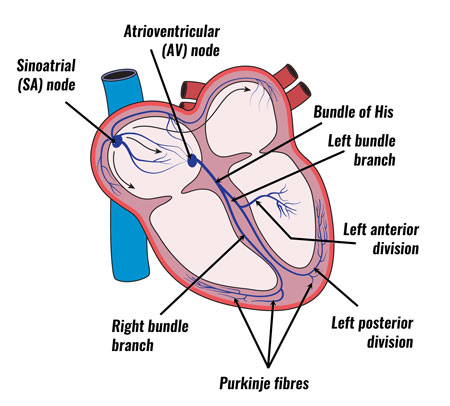

Conducting System of the Heart

The heart's ability to pump blood relies on an intrinsic electrical system that generates and conducts impulses, ensuring a coordinated and rhythmic contraction. This system consists of specialized cardiac muscle cells.

1. Sinoatrial (SA) Node

- Location: Situated in the upper part of the right atrium, near the junction with the superior vena cava (SVC). It typically occupies an area to the left of the sulcus terminalis.

- Description: It extends approximately 1 cm along the superior border of the right auricle and then tapers downwards along the crista terminalis for about 2 cm.

- Pacemaker Function: It is often referred to as the natural pacemaker of the heart because it normally initiates the electrical impulses that trigger cardiac muscle contraction. It has the highest inherent rhythmicity (typically 60-100 beats per minute).

- Innervation: Has a rich supply of both sympathetic (accelerator) and parasympathetic (vagal) (depressor) nerve fibers. These autonomic influences modulate its intrinsic rate, speeding up or slowing down the heart rate in response to the body's needs.

- Conduction: From the SA node, impulses spread through the atrial muscle (via internodal pathways) to the AV node.

2. Atrioventricular (AV) Node

- Location: A small nodule located in the inferior part of the interatrial septum, just above the attachment of the septal cusp of the tricuspid valve, near the opening of the coronary sinus.

- Function: Its primary role is to delay the electrical impulse from the atria to the ventricles. This delay (approximately 0.1 second) is crucial, allowing the atria to contract and fully empty their blood into the ventricles before ventricular contraction begins.

- Output: Gives rise to the atrioventricular (AV) bundle (Bundle of His).

3. Atrioventricular (AV) Bundle (Bundle of His)

- Origin: Arises from the AV node.

- Course: Descends along the inferior border of the membranous part of the interventricular septum.

- Branching: Upon reaching the upper part of the muscular interventricular septum, it divides into the right and left bundle branches.

4. Right Bundle Branch

- Course: Passes down the right side of the interventricular septum.

- Distribution: It is then carried across the lumen of the right ventricle, often within the moderator band (septomarginal trabecula), to the anterior wall of the right ventricle. It subsequently divides into Purkinje fibers that rapidly spread throughout the right ventricular myocardium.

5. Left Bundle Branch

- Course: Descends on the left side of the interventricular septum.

- Distribution: It quickly divides into anterior and posterior fascicles, which then fan out and spread over the entire left ventricular wall, merging with the Purkinje fiber network.

6. Purkinje Fibers

- These are specialized, large-diameter cardiac muscle fibers that rapidly conduct electrical impulses throughout the ventricular myocardium, ensuring synchronized ventricular contraction.

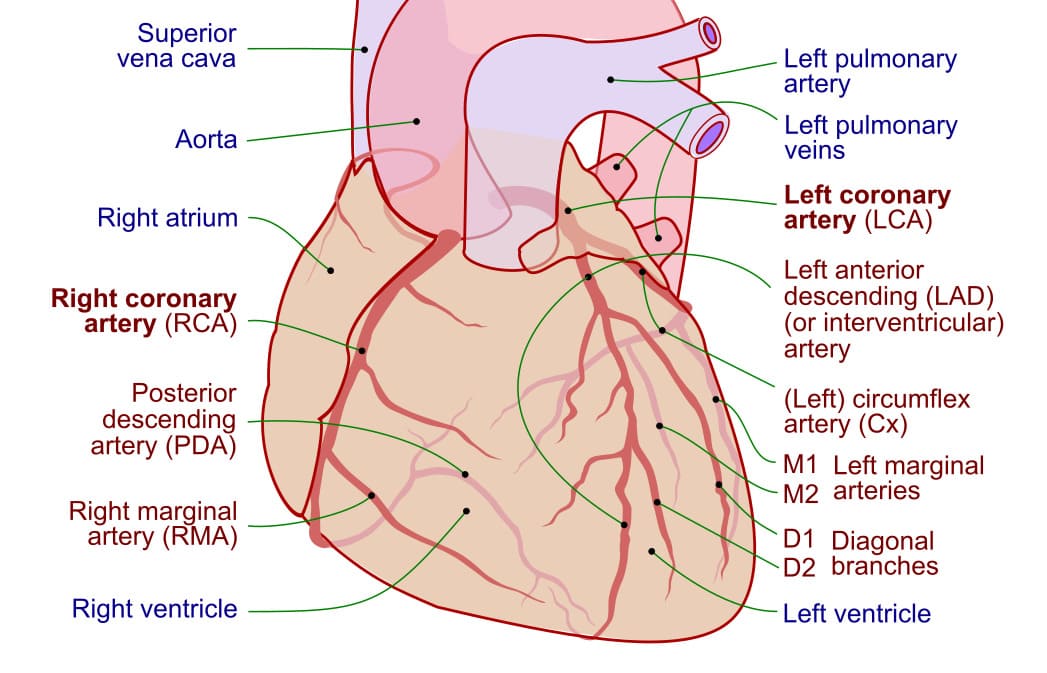

Blood Supply of the Heart (Coronary Circulation)

The heart muscle (myocardium) receives its own rich blood supply through the coronary arteries, which arise directly from the aorta.

A. Arterial Supply:

The heart is primarily supplied by two main arteries: the right coronary artery (RCA) and the left coronary artery (LCA).

Right Coronary Artery (RCA)

- Origin: Arises from the anterior (right) aortic sinus of the ascending aorta.

- Course: Passes between the right auricle and the pulmonary infundibulum, then descends vertically in the right atrioventricular groove (coronary sulcus). It reaches the inferior border of the heart, turns posteriorly, and continues in the coronary sulcus on the diaphragmatic surface.

- Major Branches and Distribution:

- Right Conus Artery: Supplies the anterior surface and upper part of the anterior wall of the right ventricle.

- Anterior Ventricular Branches (2-3): Supply the anterior part of the right ventricle.

- Marginal Branch (Acute Marginal Artery): A prominent branch that runs along the inferior margin of the right ventricle, supplying it.

- Posterior Ventricular Branches (2): Supply the diaphragmatic (inferior) part of the right ventricle.

- Posterior Interventricular (Descending) Artery (PDA): A crucial branch that descends in the posterior interventricular groove. It supplies the diaphragmatic surfaces of both the right and left ventricles, and the posterior one-third of the interventricular septum, and the AV node (in 90% of cases).

- Atrial Branches: Supply the right atrium and, in about 60% of cases, the SA node artery.

Left Coronary Artery (LCA)

- Origin: Arises from the left posterior (left) aortic sinus of the ascending aorta.

- Course: Typically shorter than the RCA, it passes between the left auricle and the pulmonary trunk, then quickly bifurcates (or trifurcates) into its main branches.

- Major Branches and Distribution:

- Anterior Interventricular (Descending) Artery (LAD): The largest branch of the LCA, it descends in the anterior interventricular groove towards the apex. It supplies the anterior two-thirds of the interventricular septum, most of the anterior wall of both ventricles (including the pulmonary conus), and the papillary muscles of the left ventricle. It often anastomoses with the posterior interventricular artery near the apex.

- Circumflex Artery (LCx): Continues in the left atrioventricular groove around the left border of the heart. It supplies the left atrium and the posterior wall of the left ventricle. It often gives off a left marginal artery (obtuse marginal) that runs along the left border. In about 40% of individuals, it gives off a sizable branch that runs on the posterior surface of the left atrium, between the pulmonary veins and the right auricle, supplying the SA node.

General Distribution Summary:

- Right Coronary Artery: Primarily supplies the right atrium, most of the right ventricle, the SA node (60%), and the AV node (90%), and the posterior one-third of the interventricular septum.

- Left Coronary Artery: Primarily supplies the left atrium, most of the left ventricle, the anterior two-thirds of the interventricular septum, and the SA node (40%).

B. Coronary Anastomosis:

- Description: While small anastomoses (connections) exist between the distal branches of the major coronary arteries (e.g., between LAD and PDA), these are generally not adequate to provide sufficient blood supply to an area of the myocardium if a major coronary artery is suddenly blocked.

- Functional End Arteries: Due to this inadequacy, the coronary arteries are often considered "functional end arteries"—meaning that while some connections exist, they are not usually sufficient to prevent tissue death (ischemia and infarction) in the event of acute occlusion of a main branch.

- Slow Blockage: If a coronary artery gradually narrows (e.g., due to atherosclerosis), the small anastomotic channels can sometimes enlarge over time, providing some collateral circulation.

- Rapid Blockage: A sudden and rapid blockage of a major coronary artery leads to ischemic necrosis (death) of the heart muscle, resulting in a myocardial infarction (heart attack).

- Angina Pectoris: Ischemia (reduced blood flow) to the heart muscle, often due to coronary artery disease, can cause angina pectoris—a severe, crushing retrosternal chest pain that can radiate to the left jaw, left shoulder, and left side of the neck.

Potential Extracardiac Anastomosis: Potential anastomoses also exist between the coronary arteries and smaller arteries outside the heart (e.g., pericardial-phrenic, bronchial, internal thoracic arteries) around the roots of the great vessels. In rare cases, these can open up to provide some blood supply to the heart if a main coronary artery is blocked.

C. Venous Drainage:

Most of the deoxygenated blood from the heart muscle drains into the right atrium, primarily via the coronary sinus and anterior cardiac veins.

- Coronary Sinus:

- The largest vein of the heart, located in the posterior part of the left atrioventricular groove. It empties directly into the right atrium.

- Tributaries of the Coronary Sinus:

- Great Cardiac Vein: Accompanies the anterior interventricular artery (LAD) and then the circumflex artery. It drains blood from the anterior part of both ventricles and the left atrium.

- Middle Cardiac Vein: Accompanies the posterior interventricular artery (PDA) and drains blood from the diaphragmatic surfaces of both ventricles.

- Small Cardiac Vein: Accompanies the right marginal artery and then the right coronary artery in the right atrioventricular groove. Drains the right ventricle and part of the right atrium.

- Posterior Vein of the Left Ventricle: Drains the posterior aspect of the left ventricle.

- Oblique Vein of the Left Atrium (Vein of Marshall): A small vein that runs on the posterior surface of the left atrium and often empties into the great cardiac vein near the coronary sinus. It is a remnant of the left superior vena cava.

- Anterior Cardiac Veins: A group of 2-4 small veins that drain directly from the anterior surface of the right ventricle into the right atrium, bypassing the coronary sinus.

- Venae Cordis Minimae (Thebesian Veins): Numerous very small veins that drain directly from the myocardial capillaries into all four chambers of the heart.

D. Lymphatic Drainage:

- Lymphatic vessels from the heart drain into several groups of lymph nodes, primarily the tracheobronchial and mediastinal lymph nodes.

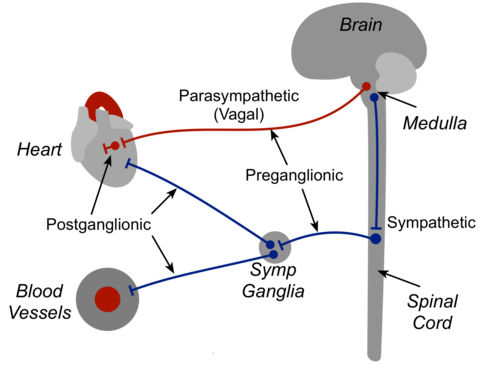

Nerve Supply of the Heart

The heart receives both sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation, which modulate its rate and force of contraction.

- Parasympathetic Innervation:

- Supplied by the vagus nerves (cranial nerve X).

- Action: Primarily causes a decrease in heart rate (bradycardia) and a reduction in the force of atrial contraction. It has less effect on ventricular contractility.

- Sympathetic Innervation:

- Supplied by fibers originating from the sympathetic trunk (specifically, upper thoracic spinal cord segments via cervical and upper thoracic ganglia).

- Action: Primarily causes an increase in heart rate (tachycardia) and an increase in the force of both atrial and ventricular contraction.

Surface Markings of Heart Valves

When listening to heart sounds (auscultation) or visualizing valve positions, it's important to understand where the valves project onto the anterior chest wall. These are not the optimal places for auscultation, but their anatomical projections.

- Tricuspid Valve: Projection: Medial end of the sternum, usually opposite the right 4th intercostal space (ICS).

- Mitral Valve: Projection: Behind the left half of the sternum, usually opposite the left 4th ICS.

- Pulmonary Valve: Projection: Medial end of the sternum, usually opposite the left 3rd costal cartilage.

- Aortic Valve: Projection: Behind the left half of the sternum, usually opposite the left 3rd ICS.

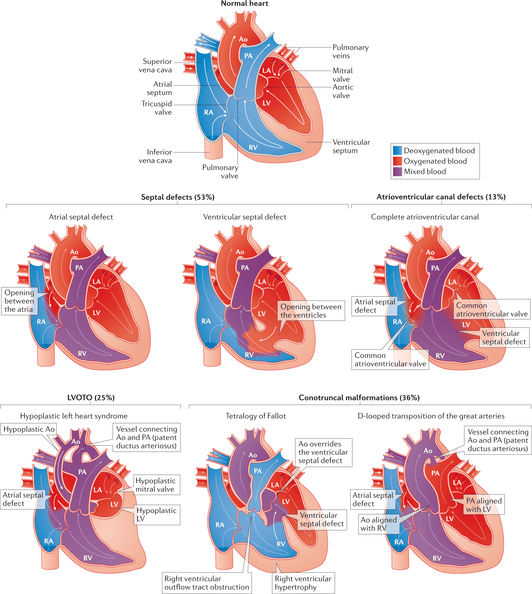

Congenital Anomalies of the Heart

These are structural defects in the heart that are present at birth.

1. Atrial Septal Defects (ASD)

- Description: A hole in the interatrial septum, allowing oxygenated blood from the left atrium to shunt to the right atrium (left-to-right shunt).

- Prevalence: Accounts for approximately 25% of all congenital heart defects (though this percentage varies depending on classification).

- Types: Several types exist, with secundum ASD being the most common.

2. Ventricular Septal Defects (VSD)

- Description: A hole in the interventricular septum, allowing oxygenated blood from the left ventricle to shunt to the right ventricle (left-to-right shunt).

- Prevalence: The most common congenital heart defect.

3. Tetralogy of Fallot

Description: A complex cyanotic (blue baby) heart defect characterized by four distinct abnormalities:

- Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD): A large hole in the interventricular septum.

- Overriding Aorta: The aorta is displaced to the right, sitting directly over the VSD, receiving blood from both ventricles.

- Pulmonary Stenosis: Narrowing of the pulmonary outflow tract (subvalvular, valvular, or supravalvular).

- Right Ventricular Hypertrophy: Thickening of the right ventricular muscle due to increased workload from pumping against the stenotic pulmonary artery and systemic pressure via the VSD.

Prevalence: Responsible for a significant proportion (around 9%) of all congenital heart defects.

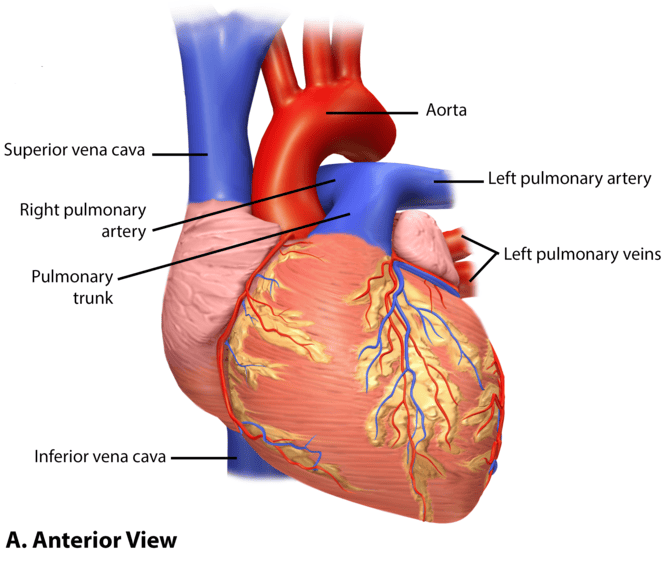

Great Vessels

The great vessels are the large arteries and veins connected to the heart. They are "great" due to their size and critical role in the systemic and pulmonary circulation.

A. Great Arteries

Aorta

The largest artery in the body, originating from the left ventricle.

Parts:

- Ascending Aorta: Rises from the left ventricle.

- Branches: Gives off the right and left coronary arteries (supplying the heart itself).

- Aortic Arch: Curves over the right pulmonary artery and the left bronchus.

- Branches: Gives off three major arteries that supply the head, neck, and upper limbs:

- i. Brachiocephalic Artery (innominate artery): Divides into the right subclavian artery and the right common carotid artery.

- ii. Left Common Carotid Artery.

- iii. Left Subclavian Artery.

- Branches: Gives off three major arteries that supply the head, neck, and upper limbs:

- Descending Aorta: Extends from the aortic arch downwards.

- a. Thoracic Aorta: The part in the thorax.

- i. Branches: Gives off various branches, including esophageal, bronchial, pericardial, and posterior intercostal arteries.

- b. Abdominal Aorta: Continues from the thoracic aorta after piercing the diaphragm at the level of T12 (not T10, as the original states, T10 is for the IVC, T8 for esophagus).

- i. Branches: Gives off numerous branches to the abdominal organs and walls:

- Three Anterior Visceral Branches: Celiac artery, superior mesenteric artery, inferior mesenteric artery (unpaired).

- Three Lateral Visceral Branches: Renal arteries, suprarenal arteries, gonadal arteries (paired, ovarian/testicular).

- Five Lateral Abdominal Wall Branches: Inferior phrenic arteries (1 pair), lumbar arteries (4 pairs).

- Three Terminal Branches: Divides at the level of L4 into the right and left common iliac arteries and the small, unpaired median sacral artery.

- i. Branches: Gives off numerous branches to the abdominal organs and walls:

- a. Thoracic Aorta: The part in the thorax.

Pulmonary Artery (Pulmonary Trunk)

- Origin: Originates from the right ventricle.

- Function: Carries deoxygenated blood to the lungs for oxygenation.

- Fetal Life: In fetal life, because the lungs are non-functional, most of the blood in the pulmonary trunk bypasses the lungs and flows directly into the aorta via the ductus arteriosus.

- Post-birth: After birth, the ductus arteriosus closes to become the ligamentum arteriosum.

B. Great Veins

Superior Vena Cava (SVC)

- Formation: Formed by the union of the right and left brachiocephalic veins.

- Brachiocephalic Vein Formation: Each brachiocephalic vein is formed by the union of the subclavian vein (drains blood from the upper limbs) and the internal jugular vein (drains blood from the brain and parts of the head/neck). The original text incorrectly states the subclavian vein returns blood from the "scalp via external jugular vein"—the external jugular vein itself drains into the subclavian, but the subclavian's primary role is upper limb.

- Drainage: Drains deoxygenated blood from the head, neck, and upper limbs into the right atrium.

Inferior Vena Cava (IVC)

- Formation: Starts at the level of L5 (not pelvic inlet) as a union of the right and left common iliac veins and receives the median sacral vein.

- Course: Ascends through the abdomen, pierces the diaphragm at the level of T8 to drain into the right atrium.

- Tributaries: Corresponds to the abdominal aorta in its tributary pattern:

- Tributaries of Origin: Median sacral vein, right and left common iliac veins.

- Anterior Visceral: Hepatic veins (right, middle, left), draining the liver.

- Lateral Visceral: Renal veins, suprarenal veins, gonadal veins.

- Posterior Abdominal Wall: Lumbar veins, inferior phrenic veins.

Azygos Venous System

- Function: Drains blood from the chest wall (intercostal veins) and thoracic viscera (e.g., esophagus, bronchi) into the superior vena cava.

- Components:

- Azygos Vein: Located on the right side of the vertebral column. It arches over the root of the right lung and drains into the SVC at the level of T4-T5 (sternal angle).

- Hemiazygos Vein: Located on the left side of the vertebral column in the lower thorax.

- Accessory Hemiazygos Vein: Located on the left side in the upper thorax.

- Connections: The hemiazygos and accessory hemiazygos veins typically drain into the azygos vein (crossing over at about T8-T9 and T7 respectively), which then drains into the SVC. (The original text had an error stating "The main azygos is found on the left" and the hemiazygos veins on the right).

Pulmonary Veins

- Number: Typically four in number (two from each lung).

- Function: Carry oxygenated blood from the lungs back to the heart.

- Drainage: End by draining into the posterior part of the left atrium.

Esophagus

The esophagus is a muscular tube that transports food from the pharynx to the stomach.

- Length: Approximately 25 cm long.

- Course: Extends from the level of the 6th cervical vertebra (C6) to the cardia of the stomach. It passes through the diaphragm at the level of the 10th thoracic vertebra (T10).

Relations

The esophagus has numerous important relations with surrounding structures:

- Anteriorly:

- Trachea (in the neck and upper thorax)

- Recurrent laryngeal nerves (traveling in the tracheoesophageal groove)

- Arch of the aorta (crosses over the left bronchus and esophagus)

- Pericardium (lining the heart)

- Left atrium (posterior to the heart)

- Diaphragm

- Left lobe of the liver

- Left vagus nerve

- Left bronchus

- Posteriorly:

- Vertebral column

- Aorta (thoracic aorta)

- Thoracic duct

- Azygos vein

- Right vagus nerve

- Right Side:

- Azygos vein

- Pleura (lining the right lung)

- Left Side:

- Thoracic duct

- Subclavian artery

- Pleura (lining the left lung)

Narrowings

The esophagus has three physiological constrictions, which are important clinically as sites where foreign bodies may lodge, or where strictures and cancers are more likely to develop.

- At the beginning: At the level of the cricopharyngeus muscle (C6).

- At the level of the sternal angle (T4/T5): Caused by the arch of the aorta and the left main bronchus crossing it.

- At T10: Where it pierces the diaphragm to enter the abdominal cavity.

Blood Supply

The esophagus receives a segmental blood supply from various arteries along its course:

- Upper 1/3: Primarily from branches of the inferior thyroid arteries.

- Mid 1/3: From direct esophageal branches of the thoracic aorta.

- Lower 1/3: From esophageal branches of the left gastric artery (a branch of the celiac trunk).

Venous Drainage

The venous drainage generally parallels the arterial supply, but with a critical distinction in the lower third.

- Upper 2/3: Drains into systemic veins, primarily the azygos vein and other smaller veins that eventually lead to the superior vena cava.

- Lower 1/3: Drains into the left gastric vein, which is a tributary of the portal venous system.

Heart & Great Vessels Quiz

Systems Anatomy

Enter your details to begin the examination.

🛡️ Privacy Note: Results are for tracking and certification purposes only.

Heart & Great Vessels Quiz

Systems Anatomy

Preparing questions...

Exam Completed!

See your performance breakdown below.