Rib Cage & Diaphragm Anatomy

The Rib Cage: An Overview

The thoracic cage, commonly known as the rib cage, is a robust bony-cartilaginous framework that forms the skeletal wall of the chest. It serves several critical functions:

- Protection: Encapsulates and safeguards vital thoracic organs, including the heart, lungs, and great vessels, as well as parts of the upper abdominal organs (liver, spleen).

- Muscle Attachment: Provides numerous points of attachment for muscles of the neck, back, chest, and upper limbs, playing a role in posture and movement.

- Respiration: Its flexible, expandable structure is fundamental to the mechanics of breathing, allowing for changes in thoracic volume during inspiration and expiration.

- Support: Forms the central axial skeleton to which the pectoral girdle and upper limbs are attached.

- Shape and Location:

- The rib cage is situated in the thorax, the region of the trunk between the neck and the abdomen.

- Its overall shape is that of a truncated cone, wider inferiorly than superiorly.

- It is characteristically flattened anteriorly and posteriorly (dorsoventrally) but rounded laterally, creating a spacious cavity within.

Boundaries of the Thoracic Cage

The thoracic cage forms a well-defined compartment with distinct boundaries:

- Anterior Boundary: Formed by the sternum (breastbone) and the articulating costal cartilages.

- Posterior Boundary: Formed by the twelve thoracic vertebrae and their associated intervertebral discs.

- Lateral Boundaries: Consist of the twelve pairs of ribs, which extend from the thoracic vertebrae posteriorly to the sternum or costal cartilages anteriorly.

- Superior Boundary: Thoracic Inlet (Superior Thoracic Aperture):

- A relatively small, kidney-shaped opening.

- Formed by: The superior aspect of the first thoracic vertebra (T1) posteriorly, the medial border of the first ribs laterally, and the superior border of the manubrium anteriorly.

- This aperture provides passage for structures (e.g., trachea, esophagus, major vessels, nerves) between the neck and the thoracic cavity.

- Inferior Boundary: Thoracic Outlet (Inferior Thoracic Aperture):

- A much larger, irregular opening.

- Formed by: The 12th thoracic vertebra (T12) posteriorly, the 11th and 12th pairs of ribs laterally, and the costal margin (formed by the cartilages of ribs 7-10) and the xiphoid process anteriorly.

- This aperture is almost completely sealed by the diaphragm, which separates the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity.

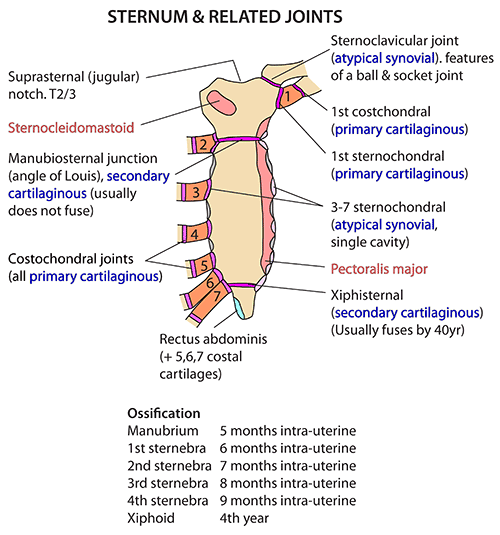

The Sternum (Breastbone)

The sternum, or breastbone, is a flat, elongated bone positioned in the central anterior aspect of the thoracic cage. It forms the anterior articulation for the ribs via their costal cartilages.

Composition: The sternum is typically divided into three fused parts:

Manubrium Sterni (Handle)

- Location: The broadest, most superior part of the sternum.

- Vertebral Level: Roughly lies opposite the T3 and T4 vertebral bodies.

- Articulations:

- Superiorly: The suprasternal (jugular) notch is at its superior border. Lateral to the notch are the clavicular notches for articulation with the clavicles (forming the sternoclavicular joints).

- Laterally: Possesses facets for articulation with the costal cartilages of the first pair of ribs and the upper half of the second pair of ribs. These are synovial joints, permitting slight movement.

- Inferiorly: Articulates with the body of the sternum at the manubriosternal joint.

Body of the Sternum (Gladiolus)

- Location: The longest, central part of the sternum.

- Articulations:

- Superiorly: Articulates with the manubrium at the manubriosternal joint.

- Laterally: Contains facets for articulation with the costal cartilages of the lower half of the second ribs through the seventh ribs.

- Inferiorly: Articulates with the xiphoid process at the xiphisternal joint.

Xiphoid Process

- Location: The smallest, most inferior part of the sternum.

- Vertebral Level: The xiphisternal joint is typically at the level of the T9 vertebral body.

- Characteristics:

- It is highly variable in shape and size.

- It generally does not articulate with any ribs.

- It remains cartilaginous in young individuals and gradually undergoes ossification (hardens into bone) from its proximal end, a process that completes in adulthood and continues into old age.

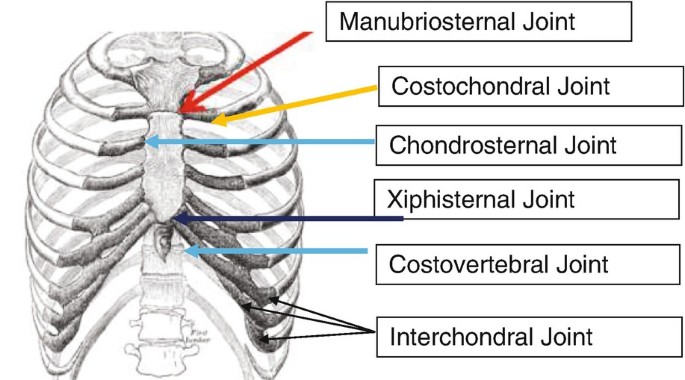

Joints of the Sternum:

- Manubriosternal Joint (Sternal Angle / Angle of Louis): A secondary cartilaginous joint (symphysis) between the manubrium and the body. It forms a palpable transverse ridge.

- Xiphisternal Joint: A secondary cartilaginous joint between the body and the xiphoid process. It typically fuses completely in older adults.

Clinical Uses of the Sternum

A. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures

- Median Sternotomy (Median Thoracotomy):

- Procedure: A surgical incision made longitudinally down the center of the sternum, which is then divided using a saw.

- Purpose: Provides wide surgical access to the mediastinum (heart, great vessels, trachea, thymus) for procedures such as cardiac surgery (e.g., coronary artery bypass grafting, valve replacement) and lung transplantation. The sternum is typically rejoined with wires post-surgery.

- Bone Marrow Biopsy/Aspiration:

- Procedure: Due to its broad, flat, and relatively superficial nature, the sternum (particularly the manubrium) is a common site for obtaining bone marrow samples. A needle is inserted into the sternum to extract marrow for diagnostic purposes (e.g., in cases of leukemia, anemia, or other hematological disorders). This site is chosen to avoid vital organs directly below and due to its accessibility.

B. Congenital Anomalies of the Sternum

Congenital malformations of the sternum primarily involve abnormalities in its shape, which can affect respiratory and cardiac function in severe cases.

- Pectus Carinatum (Pigeon Chest):

- Description: A chest wall deformity characterized by an outward protrusion of the sternum and costal cartilages.

- Appearance: Gives the chest a prominent, "pigeon-breasted" appearance.

- Clinical Significance: Usually cosmetic, but severe cases can restrict lung expansion and cardiac function, especially during strenuous exercise.

- Pectus Excavatum (Funnel Chest):

- Description: The most common sternal deformity, characterized by an inward depression of the sternum and costal cartilages.

- Appearance: Creates a "funnel-shaped" indentation in the chest.

- Clinical Significance: Ranges from mild cosmetic concerns to severe cases where the sternum compresses the heart and lungs, potentially leading to respiratory and cardiac compromise (e.g., reduced exercise tolerance).

- (The "Cup-shaped deformity" and "Saucer-shaped" descriptions in the original text likely refer to variations or degrees of Pectus Excavatum.)

- Horns-of-Steer Deformity:

- (This term is less common in standard medical literature but may refer to a specific variant of chest wall deformity where the costal cartilages project laterally or superiorly, resembling horns, often associated with other sternal defects or genetic syndromes.) It suggests unusual or distorted projections of the ribs or costal cartilages in relation to the sternum.

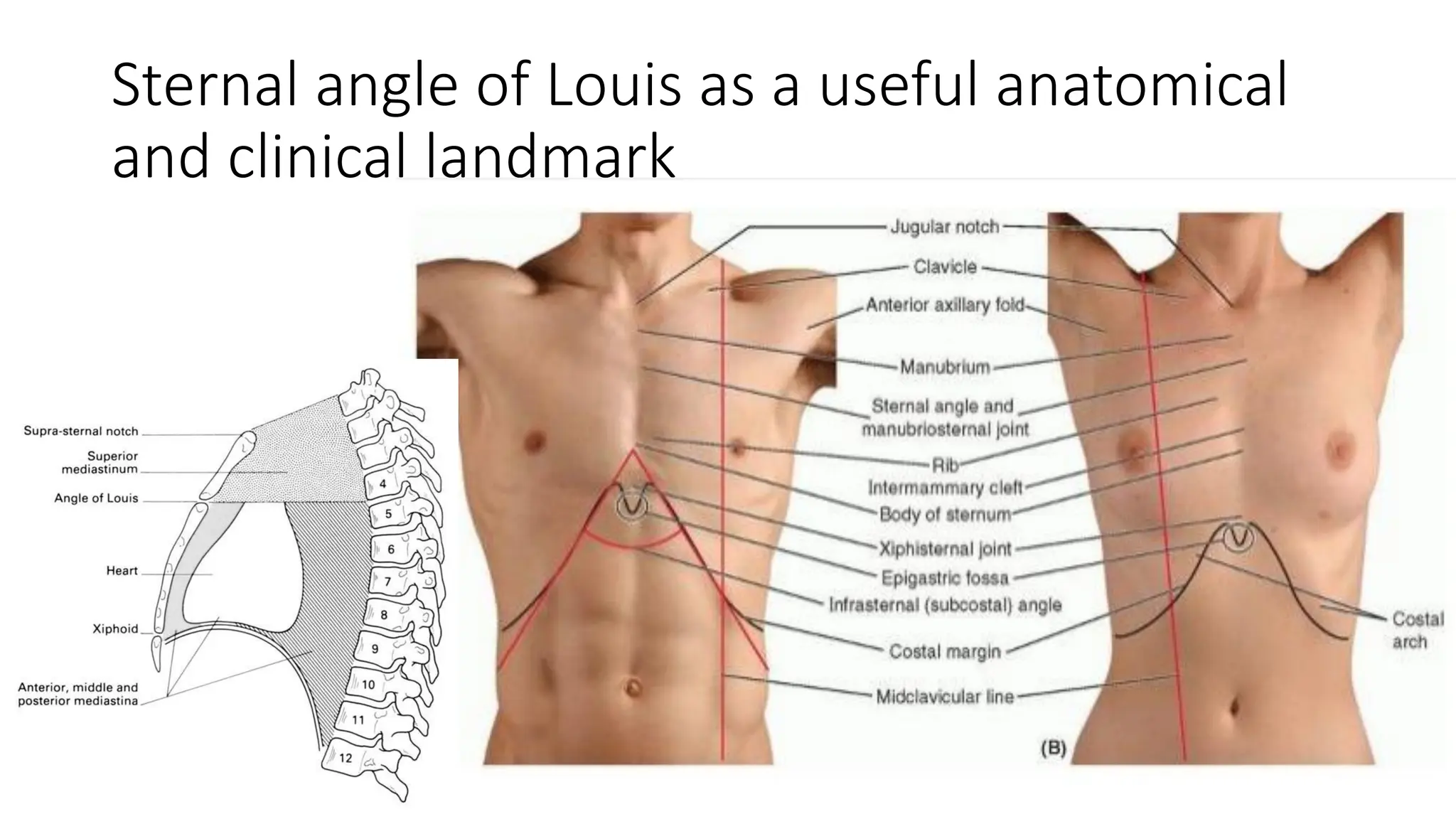

Anatomical Happenings at the Sternal Angle (Angle of Louis)

- Skeletal Level: It marks the level of the intervertebral disc between the 4th and 5th thoracic vertebrae (T4/T5) posteriorly.

- Rib Articulation: It is at the level where the costal cartilage of the second rib articulates with the sternum. This makes the second rib the easiest to identify, and from it, other ribs can be counted.

- Tracheal Bifurcation: It is the level at which the trachea bifurcates into the right and left main bronchi (at the carina).

- Aortic Arch: It marks the beginning and end of the aortic arch:

- The ascending aorta ends (or becomes the aortic arch).

- The aortic arch begins and ends, giving rise to its three major branches.

- The descending aorta begins (at the inferior aspect of the T4 vertebra).

- Great Vessels:

- The ligamentum arteriosum, a remnant of the fetal ductus arteriosus, connects the arch of the aorta to the left pulmonary artery at this level.

- The azygos vein drains into the superior vena cava (SVC) at or just above this level.

- The SVC itself enters the right atrium at this level.

- Nerve Relation: The left recurrent laryngeal nerve loops around the inferior aspect of the arch of the aorta, just posterior to the ligamentum arteriosum, ascending to the larynx.

- Mediastinal Division: It serves as the arbitrary anatomical plane that divides the superior mediastinum from the inferior mediastinum.

- Lymphatic Drainage: The main lymphatic drainage ducts (thoracic duct and right lymphatic duct) may cross or terminate in the vicinity of this level.

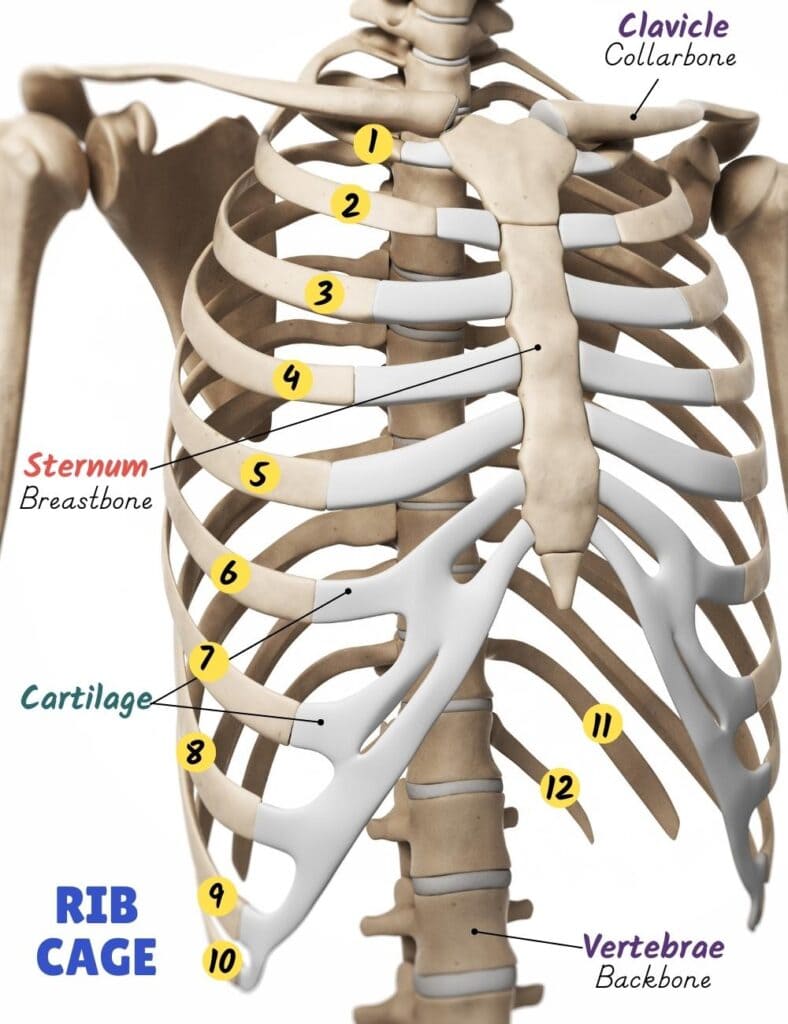

Ribs: Structure and Function

The ribs are curved, flat bones that form the greater part of the thoracic cage. In humans, there are 12 pairs of ribs.

Functions in Humans:

- Respiration: The primary function of the ribs, along with their associated muscles and cartilage, is to facilitate respiration. Their mobility allows for expansion and contraction of the thoracic cavity, essential for ventilation.

- Protection: Contrary to the original statement, the ribs provide significant protection for the delicate vital organs within the thoracic cavity (heart, lungs, great vessels) and superior abdominal organs (liver, spleen, kidneys). While severe trauma can still damage these organs even with an intact rib cage, the ribs undoubtedly reduce their vulnerability.

- Muscle Attachment: Serve as crucial attachment points for numerous muscles of the chest, back, neck, and upper limbs, playing roles in movement, posture, and respiration.

Comparative Anatomy (Other Animals - for interest, but not primary human anatomy):

- Snakes: Ribs extend almost the entire length of the trunk and are highly mobile, aiding in locomotion. (The phrase "inside feet" is incorrect for snakes, as they are limbless; their ribs are part of their axial skeleton).

- Fish: Ribs primarily provide attachment for swimming muscles and offer some protection against external pressure (including hydrostatic pressure in deep-water species).

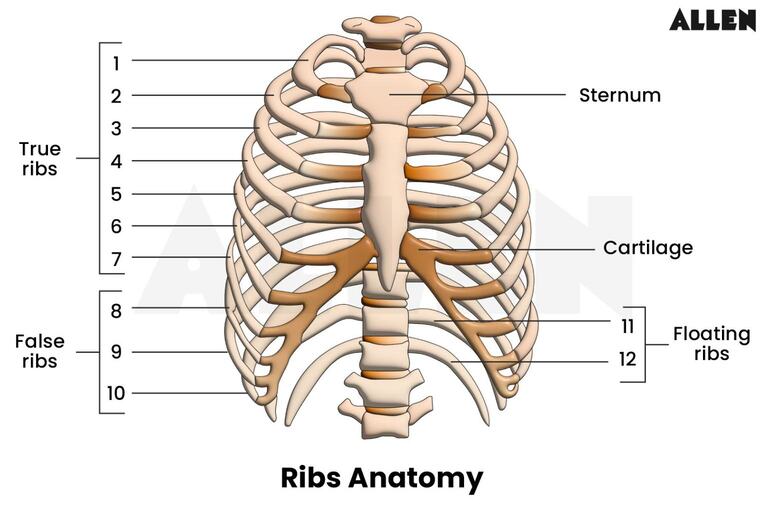

Classification of Ribs

There are 12 pairs of ribs in humans, and they are classified in two main ways:

A. Classification by Sternum Articulation:

- True Ribs (Vertebrosternal Ribs): Ribs 1-7

- Each true rib articulates directly with the sternum via its own dedicated costal cartilage.

- False Ribs (Vertebrochondral Ribs): Ribs 8-10

- These ribs do not directly articulate with the sternum. Instead, their costal cartilages attach to the costal cartilage of the rib immediately above them (typically the 7th costal cartilage), thereby indirectly articulating with the sternum.

- Floating Ribs (Vertebral/Free Ribs): Ribs 11-12

- These ribs have no anterior attachment to the sternum or to the cartilages of other ribs. Their costal cartilages end freely in the abdominal musculature.

B. Classification by Structural Features:

- Typical Ribs (Ribs 3-9): Share a common set of features (described in detail below).

- Atypical Ribs (Ribs 1, 2, 10, 11, 12): Possess unique features that distinguish them from typical ribs.

- Specific Atypical Features mentioned (and expanded):

- Ribs 1, 10, 11, and 12: Have only one articular facet on their head. This single facet articulates with the body of its numerically corresponding vertebra. (Typical ribs have two facets, articulating with their own vertebra and the one superior to it).

- Ribs 11 and 12:

- Possess no neck (the segment between the head and the tubercle).

- Possess no tubercle (the prominence for articulation with the transverse process). Therefore, they do not articulate with the transverse processes of their corresponding vertebrae, only being attached by ligaments.

Features of a Typical Rib (Ribs 3-9)

A typical rib (ribs 3-9) is characterized by the following anatomical features:

- Head: The posterior, expanded end of the rib.

- It has two articular facets (demifacets), separated by a crest.

- The inferior facet articulates with the superior costal facet on the body of its numerically corresponding vertebra.

- The superior facet articulates with the inferior costal facet on the body of the vertebra superior to it.

- Neck: The flattened, constricted portion extending laterally from the head.

- Tubercle: A prominence located at the junction of the neck and shaft.

- It has two parts:

- Articular part: A smooth facet that articulates with the transverse process of its numerically corresponding vertebra (forming a costotransverse joint).

- Non-articular part: A roughened elevation for the attachment of the costotransverse ligament.

- It has two parts:

- Angle: The point of greatest curvature of the rib, located just lateral to the tubercle. It also serves as an attachment point for certain muscles.

- Shaft (Body): The main, elongated, curved part of the rib.

- It is generally smooth on its superior border and sharp on its inferior border.

- Costal Groove: Along the inferior inner surface of the shaft, there is a prominent costal groove. This groove provides a protected pathway for the intercostal vein, artery, and nerve (VAN – running from superior to inferior within the groove).

- Anterior End: The anterior end of the shaft is roughened and articulates with the costal cartilage.

Atypical Ribs (Ribs 1, 2, 10, 11, 12)

The atypical ribs possess distinct features that differentiate them from the typical ribs:

First Rib (Rib 1):

- Unique Characteristics: It is the shortest, broadest, and most sharply curved of all ribs.

- Flattening: It is horizontally flattened, with superior and inferior surfaces (unlike other ribs which have medial and lateral surfaces).

- Head: Has only one articular facet for articulation with the body of the T1 vertebra.

- Neck & Tubercle: Has a distinct neck and tubercle, with the tubercle articulating with the transverse process of T1.

- Superior Surface Features:

- Scalene Tubercle: A prominent roughened projection on its superior surface, midway along the medial border, for the insertion of the scalenus anterior muscle.

- Grooves:

- Anterior to the scalene tubercle: A shallow groove for the subclavian vein.

- Posterior to the scalene tubercle: A deeper groove for the subclavian artery and the lower trunk of the brachial plexus.

- Clinical Significance: Due to its close relation to the subclavian artery and brachial plexus, abnormalities or trauma to the first rib can lead to Thoracic Outlet Syndrome.

Second Rib (Rib 2):

- Length & Curvature: Longer and less curved than the first rib, but still more curved than typical ribs.

- Head: Has two articular facets (for T1 and T2 vertebrae), but its angle of curvature is sharp.

- Tuberosity for Serratus Anterior: A prominent roughened area on its outer (lateral) surface, near its angle, for the origin of the serratus anterior muscle.

Tenth Rib (Rib 10):

- Head: Similar to the first rib, its head usually has only one articular facet, articulating solely with the body of the T10 vertebra. (Sometimes it may have two, making it typical).

Eleventh Rib (Rib 11):

- Head: Has only one articular facet for articulation with the body of the T11 vertebra.

- No Neck: The neck is virtually absent.

- No Tubercle: Lacks a prominent tubercle, and therefore does not articulate with the transverse process of T11.

- No Costal Groove: The costal groove is very shallow or absent.

Twelfth Rib (Rib 12):

- Head: Similar to the 11th rib, its head has only one articular facet for articulation with the body of the T12 vertebra.

- No Neck or Tubercle: It also lacks a neck and a tubercle, and thus does not articulate with the transverse process of T12.

- No Costal Groove: Costal groove is absent.

- Length: Often shorter than the 11th rib.

Joints of the Ribs

The ribs form several important articulations within the thoracic cage, allowing for the necessary flexibility for respiration.

Costovertebral Joints (Posterior Articulations):

A. Joints of the Heads of the Ribs:

- Type: Synovial plane joints.

- Articulations:

- Typical Ribs (2-9): The head of each rib articulates with two vertebral bodies (its own number and the one above) and the intervertebral disc between them.

- Atypical Ribs (1, 10, 11, 12): The head of each articulates with only one vertebral body (its own number).

- Movement: Limited gliding movements, contributing to the "pump-handle" and "bucket-handle" movements of the rib cage during respiration.

B. Costotransverse Joints:

- Type: Synovial plane joints.

- Articulations: Formed between the tubercle of a rib and the transverse process of its numerically corresponding vertebra.

- Presence: Present for ribs 1-10. Ribs 11 and 12 lack tubercles and transverse process articulations.

- Movement: Allow slight gliding and rotational movements.

Sternocostal Joints (Anterior Articulations):

A. Costochondral Joints:

- Type: Primary cartilaginous joints (synchondroses).

- Articulations: Between the anterior end of the rib and the lateral end of its costal cartilage.

- Movement: No movement is possible at these joints; the cartilage is firmly united to the bone.

B. Chondrosternal (Sternocostal) Joints:

- Articulations: Between the medial ends of the costal cartilages and the sternum.

- Type:

- 1st Rib: Forms a primary cartilaginous joint (synchondrosis) with the manubrium. No movement is possible.

- Ribs 2-7: Form synovial plane joints with the sternum (body or manubrium). These joints allow for slight gliding movements, crucial for respiratory mechanics.

C. Interchondral Joints:

- Articulations: Formed between the costal cartilages of ribs 8, 9, and 10, where they attach to the cartilage immediately above.

- Type: Mostly synovial plane joints, but the 9th and 10th may be fibrous.

Floating Ribs (Ribs 11 and 12): Their anterior ends and costal cartilages do not articulate with the sternum or other costal cartilages; they terminate freely in the abdominal wall musculature.

Clinical Notes on Ribs

The ribs are frequently involved in trauma and various medical conditions due to their superficial location and integral role in respiration.

1. Flail Chest:

- Cause: A life-threatening condition resulting from multiple rib fractures in two or more places on the same side, or fracture of the sternum combined with fractures of multiple ribs. This creates a segment of the thoracic wall that is no longer rigidly attached to the rest of the rib cage.

- Paradoxical Movement: During inspiration, the flail segment is sucked inward by the negative intrathoracic pressure. During expiration, it is pushed outward by the positive intrathoracic pressure. This "paradoxical movement" impairs effective ventilation and gas exchange.

- Complications: Often associated with underlying lung contusion, leading to severe respiratory distress.

2. Rib Grafts:

- Usage: Ribs are a common source of autologous bone grafts (bone harvested from the patient's own body). Their curved shape and cancellous (spongy) bone content make them suitable for reconstructing various bony defects.

- Example: As mentioned, they can be used to replace the mandible (lower jawbone) following a mandibulectomy (surgical removal of part or all of the mandible), for instance, due to cancer. They can also be used in facial reconstruction, orthopedic procedures, and spinal fusion.

3. Rib Contusion:

- Cause: A bruise to the rib or surrounding tissues, typically resulting from direct trauma to the chest.

- Symptoms: Localized pain, tenderness, and swelling. Unlike a fracture, there is no break in the bone.

- Misconception in Original: The statement "Small hemorrhage below peritoneum" seems to be an error or misplacement. A rib contusion itself involves soft tissue and bone, but bleeding below the peritoneum (which lines the abdominal cavity) would indicate intra-abdominal injury, potentially from a fractured rib piercing the diaphragm and abdominal organs, not just a simple contusion. A rib contusion would cause hemorrhage within the chest wall musculature or periosteum.

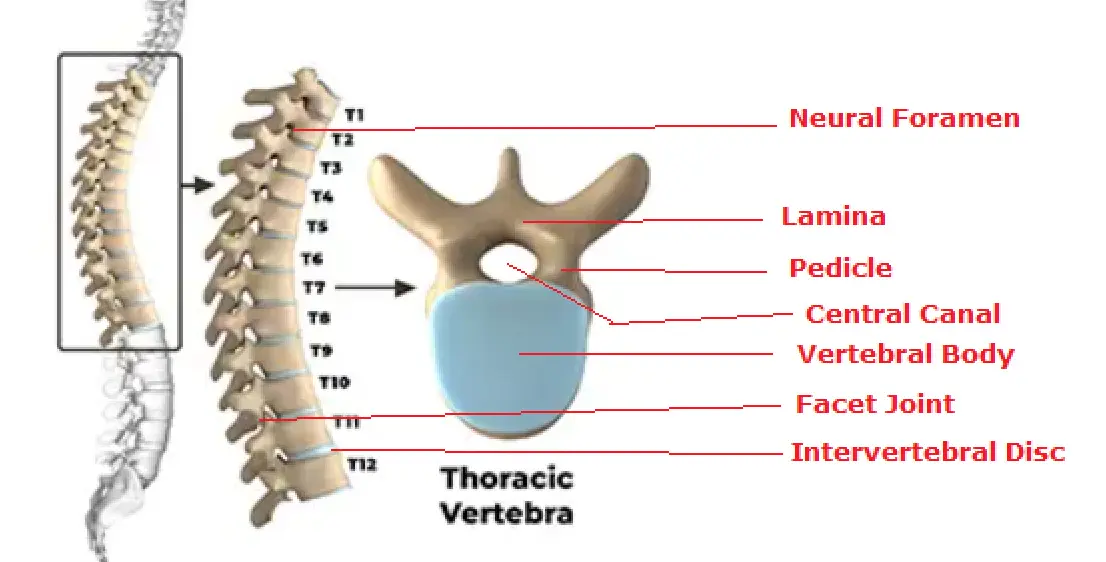

Vertebrae: General Features and Thoracic Vertebrae

The vertebrae are the irregular bones that form the vertebral column (spine), providing support, protection for the spinal cord, and points of attachment for muscles.

A. General Features of a Typical Vertebra:

- Main Parts:

- Vertebral Body (Anterior): The large, cylindrical anterior portion that bears weight.

- Vertebral Arch (Posterior): Formed by two pedicles and two laminae, which enclose the vertebral foramen. (The original text's "anterior arch and posterior body" is generally reversed; the body is anterior, the arch is posterior).

- Processes (7 in total): Arising from the vertebral arch, these serve as attachment points for muscles and ligaments, and for articulation with adjacent vertebrae:

- Spinous Process (1): Projects posteriorly (the "spine" you can feel).

- Transverse Processes (2): Project laterally from the junction of the pedicle and lamina.

- Superior Articular Processes (2): Project superiorly, with smooth superior articular facets for articulation with the inferior articular facets of the vertebra above.

- Inferior Articular Processes (2): Project inferiorly, with smooth inferior articular facets for articulation with the superior articular facets of the vertebra below.

- Vertebral Foramen: The opening enclosed by the vertebral body and arch, which collectively form the vertebral canal that houses the spinal cord.

B. Regions of the Vertebral Column and Number of Vertebrae:

- Cervical (C1-C7): 7 vertebrae in the neck.

- Thoracic (T1-T12): 12 vertebrae in the chest region.

- Lumbar (L1-L5): 5 vertebrae in the lower back.

- Sacral (S1-S5): 5 fused vertebrae forming the sacrum.

- Coccygeal (Co1-Co4): Typically 4 small fused vertebrae forming the coccyx (tailbone).

C. Distinctive Features of Thoracic Vertebrae (T1-T12):

- Number: There are 12 thoracic vertebrae.

- Vertebral Body: They have a medium-sized, heart-shaped body (when viewed superiorly).

- Vertebral Foramen: Generally small and circular.

- Spinous Process: Characteristically long and slender, sloping sharply downwards (inferiorly), often overlapping the vertebra below. This downward slope limits hyperextension.

- Costal Facets (Demifacets) on Bodies: All thoracic vertebrae have articular facets (or demifacets) on their lateral sides of the bodies for articulation with the heads of the ribs.

- Typical thoracic vertebrae (T2-T9) have two demifacets on each side: a superior one and an inferior one.

- Atypical thoracic vertebrae (T1, T10-T12) have variations, often a single full facet.

- Costal Facets on Transverse Processes: Thoracic vertebrae (T1-T10) possess articular facets on their transverse processes for articulation with the tubercles of the ribs (forming costotransverse joints).

- T11 and T12 lack these facets on their transverse processes, as ribs 11 and 12 do not have tubercles or articulate with transverse processes.

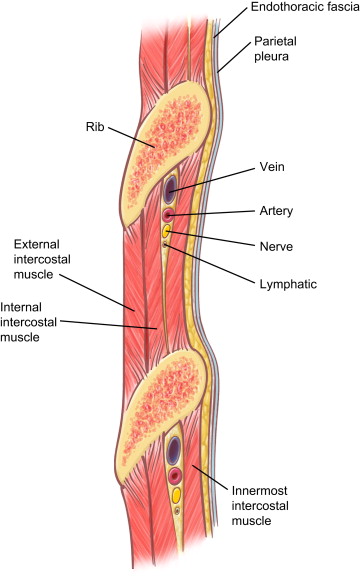

Anatomy of a Typical Intercostal Space

An intercostal space is the anatomical region between two adjacent ribs. Each space contains a neurovascular bundle that runs along the inferior margin of the rib superior to it, protected within the costal groove. The primary components of this bundle are arranged from superior to inferior as Vein, Artery, Nerve (VAN).

Contents of a Typical Intercostal Space:

- Intercostal Nerve (1 per space): A ventral ramus of a thoracic spinal nerve.

- Intercostal Arteries (typically 3 per space):

- a. One posterior intercostal artery.

- b. Two anterior intercostal arteries.

- Intercostal Veins (typically 3 per space):

- a. One posterior intercostal vein.

- b. Two anterior intercostal veins.

Muscles: The intercostal spaces are primarily filled with three layers of intercostal muscles: external, internal, and innermost intercostals.

Intercostal Nerves

The intercostal nerves are the ventral rami of the first eleven thoracic spinal nerves (T1-T11). The ventral ramus of T12 is called the subcostal nerve.

- Type: They are mixed nerves, containing both motor and sensory fibers.

- Course:

- Each nerve emerges from the intervertebral foramen and immediately enters its respective intercostal space.

- Initially, they run between the parietal pleura and the innermost intercostal muscle.

- For the majority of their course, they lie in the costal groove on the inferior border of the rib, positioned between the internal intercostal muscle and the innermost intercostal muscle (or transversus thoracis group), along with the intercostal artery and vein (VAN bundle).

- Branches and Distribution:

- Motor Branches: Supply the intercostal, subcostal, transversus thoracis, levatores costarum, and serratus posterior muscles, aiding in respiration.

- Collateral Branch: Given off near the angle of the rib, it runs along the superior border of the rib below, supplying the intercostal muscles, parietal pleura, and periosteum of the ribs.

- Lateral Cutaneous Branch: Pierces the intercostal muscles and fascia, emerging laterally to supply the overlying skin of the lateral thoracic and abdominal walls. It divides into anterior and posterior branches.

- Anterior Cutaneous Branch (Terminal Branch): The continuation of the main nerve, it pierces the intercostal muscles, fascia, and pectoralis major/abdominal muscles anteriorly to supply the skin over the anterior aspect of the thorax and abdomen.

- Lower Intercostal and Subcostal Nerves (T7-T12):

- These nerves pass from their intercostal spaces inferiorly and anteriorly, crossing the costal margin.

- They continue to run between the muscle layers of the anterior abdominal wall, supplying the abdominal muscles (external oblique, internal oblique, transversus abdominis) and the skin of the anterior abdominal wall. The subcostal nerve (T12) also plays a significant role in supplying the abdominal muscles and skin below the umbilicus.

Intercostal Arteries

The intercostal spaces receive a rich arterial supply from both posterior and anterior sources, forming an anastomotic network.

A. Posterior Intercostal Arteries (11 pairs):

- These arteries supply the posterior and lateral aspects of the intercostal spaces.

- Upper Two Spaces (1st and 2nd):

- Supplied by branches of the superior intercostal artery.

- The superior intercostal artery is a branch of the costocervical trunk, which in turn arises from the second part of the subclavian artery.

- Lower Nine Spaces (3rd-11th):

- Supplied directly by branches of the thoracic aorta.

- Subcostal Artery: The artery in the 12th space, running inferior to the 12th rib, is called the subcostal artery and is also a branch of the thoracic aorta.

B. Anterior Intercostal Arteries (9 pairs, not 11-12 pairs as per number of spaces for anterior supply):

- These arteries supply the anterior aspects of the intercostal spaces.

- Upper Six Spaces (1st-6th):

- Arise as direct branches from the internal thoracic artery (also known as the internal mammary artery).

- Lower Three Spaces (7th-9th):

- Arise from the musculophrenic artery, which is one of the two terminal branches of the internal thoracic artery (the other being the superior epigastric artery).

- (Note: The 10th and 11th intercostal spaces generally do not receive anterior intercostal arterial supply, as their cartilages are short or absent; the 12th space has no anterior intercostal artery due to the nature of the floating rib).

- Anastomoses: The posterior and anterior intercostal arteries anastomose (connect) within each intercostal space, ensuring collateral blood supply to the region.

Intercostal Veins

- The drainage pattern of the intercostal veins generally mirrors the arterial supply, although with some asymmetry, particularly on the left side.

- General Pattern: Each intercostal space typically contains:

- One posterior intercostal vein.

- Two anterior intercostal veins.

- General Pattern: Each intercostal space typically contains:

A. Anterior Intercostal Veins:

- These veins drain the anterior part of the intercostal spaces.

- They drain into the internal thoracic veins (for spaces 1-6) and the musculophrenic veins (for spaces 7-9), corresponding to their arterial supply.

- The internal thoracic veins eventually drain into the brachiocephalic veins.

B. Posterior Intercostal Veins:

- These veins drain the posterior and lateral parts of the intercostal spaces. Their drainage is more complex and asymmetrical:

- 1st Posterior Intercostal Vein:

- Usually drains directly into the vertebral vein or the brachiocephalic vein (left or right).

- 2nd, 3rd, and sometimes 4th Posterior Intercostal Veins:

- On the right side, they typically unite to form the right superior intercostal vein, which then drains into the azygos vein.

- On the left side, they usually unite to form the left superior intercostal vein, which drains into the left brachiocephalic vein.

- Remaining Posterior Intercostal Veins (typically 5th-11th):

- On the right side, they drain directly into the azygos vein.

- On the left side, the 5th-8th (or 9th) drain into the accessory hemiazygos vein, and the 9th-11th drain into the hemiazygos vein. Both the accessory hemiazygos and hemiazygos veins typically drain into the azygos vein.

- 1st Posterior Intercostal Vein:

- Subcostal Vein (12th space): Drains into the azygos vein on the right and the hemiazygos vein on the left.

Thoracic Inlet (Superior Thoracic Aperture)

The thoracic inlet, also known as the superior thoracic aperture, is the opening at the top of the thoracic cage that serves as a passageway for structures moving between the neck and the thorax. It is an important anatomical bottleneck.

- Location: An obliquely oriented opening situated between the neck superiorly and the thoracic cavity inferiorly.

- Boundaries:

- Anteriorly: The superior border of the manubrium sterni (the "sternal notch" is a palpable depression in its midline).

- Laterally: The medial borders of the first pair of ribs and their costal cartilages.

- Posteriorly: The superior border of the body of the first thoracic vertebra (T1).

- Contents: Numerous vital structures pass through this relatively narrow opening, including the trachea, esophagus, common carotid and subclavian arteries, internal jugular and subclavian veins, vagus and phrenic nerves, brachial plexus, and apex of the lungs covered by pleura.

- Roof: The thoracic inlet is effectively roofed by the suprapleural membrane (Sibson's fascia), which reinforces the cervical dome of the pleura.

Thoracic Inlet Syndrome (Thoracic Outlet Syndrome)

Location of Compression: The "thoracic outlet" refers to the space (not an opening) through which the neurovascular bundle passes from the neck into the arm. Key areas of compression include:

- Scalene Triangle: Formed by the anterior and middle scalene muscles and the first rib.

- Costoclavicular Space: Between the clavicle and the first rib.

- Pectoralis Minor Space: Beneath the pectoralis minor muscle.

- Cervical Rib: A congenital anomaly where an extra rib develops from the C7 vertebra. This extra rib can significantly narrow the thoracic outlet, compressing the subclavian artery and the lower trunk of the brachial plexus.

- Anomalous Fibrous Bands: Connective tissue bands that are present from birth.

- Muscle Anomalies: Hypertrophy or abnormal insertion of scalene muscles.

- Trauma: Fractures of the clavicle or first rib, whiplash injuries.

- Repetitive Arm and Shoulder Movements: Can contribute to muscle hypertrophy and compression.

- Neurogenic TOS (most common): Compression of the brachial plexus leads to pain, numbness, tingling (paresthesia), and weakness in the arm, hand, and fingers.

- Arterial TOS: Compression of the subclavian artery can cause:

- Ischemic pain (pain due to reduced blood flow, especially during exertion).

- Coldness, pallor, and fatigue in the arm and hand.

- Reduced or absent pulses in the affected limb.

- Venous TOS: Compression of the subclavian vein can lead to swelling, discoloration (cyanosis), and a feeling of heaviness in the arm, often referred to as Paget-Schroetter syndrome.

Suprapleural Membrane (Sibson's Fascia)

The suprapleural membrane, also known as Sibson's fascia, is a strong, dense fascial layer that reinforces the cervical pleura at the thoracic inlet.

- Location: It forms a fibrous dome or cap over the apex of the lung and the cervical pleura, stretching across the thoracic inlet.

- Attachments:

- Laterally: Attached to the inner border (medial border) of the first rib and its costal cartilage. (The original note "Not attached to neck of 1st rib" is accurate as its attachment is more medial to the rib's neck).

- Posteriorly: Attached to the transverse process of the seventh cervical vertebra (C7).

- Anteriorly: Merges with the inner aspects of the manubrium.

- Medially: It becomes thinner and blends with the mediastinal pleura.

- Orientation: It lies in the same oblique plane as the thoracic inlet itself.

- Relationship to Cervical Pleura: The cervical dome (cupula) of the parietal pleura is directly attached to and supported by the undersurface of the suprapleural membrane.

- Relationship to Neurovascular Structures: Crucially, the subclavian vessels (artery and vein) and the brachial plexus (and other structures passing into the upper limb) pass superior to (on its outer surface) the suprapleural membrane as they cross the first rib.

- Function: Its primary function is to provide rigidity and structural support to the thoracic inlet. By doing so, it prevents the cervical pleura and the apex of the lung from being sucked up into the neck during the significant pressure changes that occur within the thoracic cavity during deep inspiration (negative intrathoracic pressure).

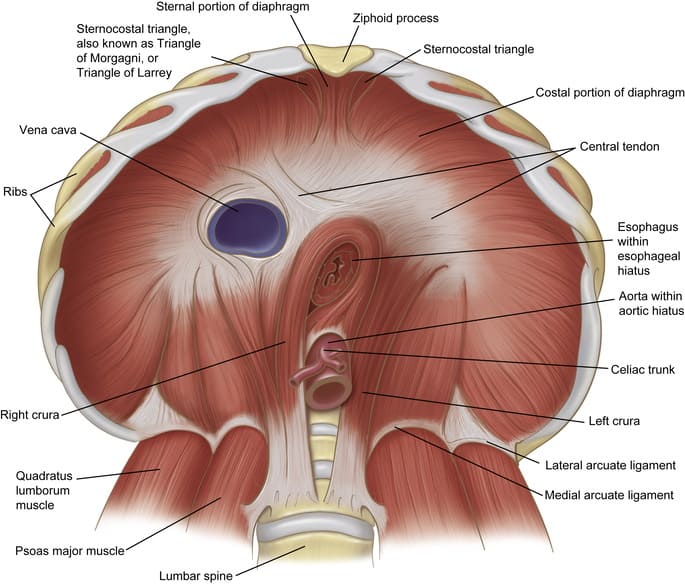

Thoracic Outlet (Inferior Thoracic Aperture)

The thoracic outlet, also known as the inferior thoracic aperture, is the large, irregular opening at the bottom of the thoracic cage. It forms the boundary between the thoracic and abdominal cavities.

- Location: Forms the broad, inferior anatomical exit of the thoracic cavity.

- Boundaries:

- Anteriorly: The xiphoid process of the sternum.

- Anterolaterally: The costal arch (or subcostal margin), which is formed by the conjoined costal cartilages of ribs 7-10.

- Posterolaterally: The tips of the 11th and 12th ribs.

- Posteriorly: The body of the twelfth thoracic vertebra (T12).

- Covering: Unlike the thoracic inlet, the thoracic outlet is almost entirely closed off by the large, dome-shaped diaphragm, a musculofibrous septum.

- Passages through the Diaphragm: The diaphragm, while forming a barrier, contains several essential openings (hiatuses) that allow for the passage of vital structures between the thorax and the abdomen. These include:

- Vena Caval Foramen: For the inferior vena cava.

- Esophageal Hiatus: For the esophagus and vagus nerves.

- Aortic Hiatus: For the aorta, thoracic duct, and azygos vein.

- Other smaller openings for nerves and vessels.

Diaphragm

The diaphragm is a large, dome-shaped musculofibrous septum that separates the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity. It is the primary muscle of respiration.

- Location: Situated at the base of the thoracic cavity, inferior to the lungs and heart, and superior to the abdominal organs. (The term "distal to the lungs" is anatomically imprecise; "inferior to the lungs" is more accurate).

- Presence: The diaphragm is a characteristic feature of mammals (including placental mammals, but also monotremes and marsupials), not exclusively "placentalia."

- Structure: It is composed of two main parts:

- Peripheral Muscular Part: Consists of skeletal muscle fibers that originate from the circumference of the thoracic outlet (sternum, lower six costal cartilages and ribs, and lumbar vertebrae) and ascend to insert into the central tendon.

- Central Tendon: A strong, aponeurotic (tendinous) structure located in the center of the diaphragm. It is trilobate (trefoil shaped) and is the highest point of the diaphragm when relaxed.

- Essential Function: Its most critical function is respiration, specifically inspiration. Contraction of the diaphragm flattens its domes, increasing the vertical dimension of the thoracic cavity and drawing air into the lungs.

- Domes: The diaphragm consists of a right dome and a left dome.

- The right dome is typically higher than the left dome.

- This difference in height is primarily attributed to the presence of the large liver occupying space beneath the right dome, pushing it superiorly.

Diaphragmatic Apertures (Openings)

The diaphragm, despite being a muscular barrier, contains several essential openings or "apertures" that allow structures to pass between the thoracic and abdominal cavities.

A. Major Diaphragmatic Apertures:

| Aperture | Vertebral Level | Location | Structures Passing Through |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Caval Opening (Foramen for Vena Cava) | Approximately T8 | Within the central tendon of the diaphragm. |

i. Inferior Vena Cava (IVC): The largest vein, returning deoxygenated blood from the lower body. It is often intimately fused with the margins of the opening. ii. Terminal branches of the Right Phrenic Nerve: Primarily sensory fibers to the diaphragm and surrounding pleura/pericardium. iii. Lymphatic vessels from the liver. |

| 2. Esophageal Hiatus | Approximately T10 | Within the muscular part of the diaphragm, formed mainly by the right crus. |

i. Esophagus: The muscular tube connecting the pharynx to the stomach. ii. Vagus Nerves (Anterior and Posterior Trunks): Innervating abdominal organs. iii. Esophageal branches of the Left Gastric Artery and Vein: Supplying the distal esophagus. iv. Lymphatic vessels. |

| 3. Aortic Hiatus | Approximately T12 | Posterior to the diaphragm, formed by the right and left crura and the vertebral column. It is technically behind the diaphragm and not an opening through the diaphragm itself. |

i. Aorta: The main artery carrying oxygenated blood from the heart. ii. Azygos Vein: On the right side, draining the posterior thoracic wall. iii. Thoracic Duct: The largest lymphatic vessel in the body. |

B. Other Smaller Openings and Passages:

These openings are often less formally defined and can vary.

- Openings associated with the Crura:

- Right Crus: Typically allows passage for the Greater and Lesser Right Splanchnic Nerves.

- Left Crus: Typically allows passage for the Greater and Lesser Left Splanchnic Nerves, and sometimes the Hemiazygos Vein on the left side.

- Openings between Sternal & Costal Parts (Foramina of Morgagni/Larrey's spaces):

- Located anteriorly, between the sternal and costal attachments of the diaphragm.

- Structures Passing Through:

- i. Superior Epigastric Arteries and Veins (terminal branches of the internal thoracic vessels).

- ii. Lymphatic vessels.

- Sympathetic Trunks: Pass posterior to the diaphragm, deep to the medial arcuate ligaments.

Actions of the Diaphragm

The diaphragm's primary role is in respiration, but its contraction and relaxation are also vital for many other physiological processes that involve increasing intra-abdominal pressure.

- Respiration:

- Primary Muscle of Inspiration: Contraction of the diaphragm causes its domes to flatten and descend, significantly increasing the vertical dimension of the thoracic cavity. This creates negative pressure within the lungs, drawing air in.

- Relaxation for Expiration: During quiet breathing, relaxation of the diaphragm allows it to ascend passively, reducing thoracic volume and expelling air.

- Increased Intra-abdominal Pressure: The diaphragm's contraction, in conjunction with the contraction of the abdominal wall muscles, dramatically increases intra-abdominal pressure. This is essential for:

- Forced Expiration (e.g., Sneezing and Coughing): While not the primary muscle of forced expiration, the diaphragm plays a role in building up pressure.

- Defecation: Bearing down to expel feces.

- Urination: Assisting in bladder emptying.

- Parturition (Childbirth): "Pushing" during labor.

- Vomiting: Contributing to the expulsion of gastric contents.

- Weight Lifting / Valsalva Maneuver: Stabilizing the trunk to provide a rigid base for limb movements.

- Thoracoabdominal Pump (Venous Return): The cyclical descent and ascent of the diaphragm during respiration create pressure gradients that assist in venous return of blood to the heart (the "thoracoabdominal pump") and lymphatic flow from the abdomen into the thoracic duct.

Nerve Supply:

- The diaphragm is exclusively innervated by the phrenic nerves (right and left).

- Each phrenic nerve (C3, C4, C5 keep the diaphragm alive!) supplies the motor innervation to its respective half of the diaphragm, as well as sensory innervation to the central part of the diaphragm, pleura, and pericardium.

Clinical Correlates of the Diaphragm

Given its critical role and complex development, the diaphragm is subject to various clinical conditions.

Congenital Anomalies:

- Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (CDH): This is a serious birth defect where there is an incomplete closure of the diaphragm during fetal development, most commonly on the left side (Bochdalek hernia). This "hole" allows abdominal organs (e.g., intestines, stomach, spleen, liver) to herniate (protrude) into the thoracic cavity.

- Consequences: The presence of abdominal organs in the chest space prevents the normal development of the lungs (pulmonary hypoplasia) and can lead to severe respiratory distress and pulmonary hypertension in newborns. The phrase "Intestine protruding through hole in diaphragm" directly refers to this condition.

- Hiatal Hernia: While typically acquired, some forms can have a congenital component. This involves the protrusion of a part of the stomach into the thorax through the esophageal hiatus (enlarged opening for the esophagus).

- Cause: Severe trauma to the abdomen or chest, such as from motor vehicle accidents, falls, or penetrating injuries (stabbing, gunshot wounds), can cause a tear or rupture in the diaphragm.

- Consequences: Abdominal contents can then herniate into the chest, leading to respiratory compromise, strangulation of organs, and difficulty in diagnosis due to often subtle symptoms initially.

- Cause: Damage to one or both phrenic nerves can lead to partial (paresis) or complete paralysis of the diaphragm on the affected side.

- Unilateral Paralysis: Often caused by trauma, tumors (e.g., lung cancer invading the nerve), or nerve compression. Patients may be asymptomatic at rest but experience dyspnea (shortness of breath) on exertion, especially when lying down. The affected dome of the diaphragm will rise paradoxically during inspiration.

- Bilateral Paralysis: Much more severe and life-threatening, often requiring mechanical ventilation. Causes can include spinal cord injury, neuromuscular diseases (e.g., Guillain-Barré syndrome, ALS), or bilateral phrenic nerve damage.

Rib Cage & Diaphragm Quiz

Systems Anatomy

Enter your details to begin the examination.

🛡️ Privacy Note: Results are for tracking and certification purposes only.

Rib Cage & Diaphragm Quiz

Systems Anatomy

Preparing questions...

Exam Completed!

See your performance breakdown below.