Upper Respiratory Anatomy

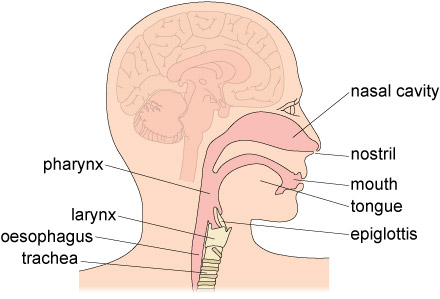

Respiratory Tract

The respiratory tract is the pathway for air, comprising structures that transport, filter, warm, and humidify air for gas exchange in the lungs. It is divided into the upper (nose, nasal cavity, pharynx, larynx) and lower (trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, alveoli) tracts. Key functions include oxygenating blood and removing carbon dioxide.

The respiratory system is functionally and anatomically divided into two main parts:

Upper Respiratory Tract (URT)

Extends from the external nares (nostrils) to the larynx (voice box). Includes the nose (external nose and nasal cavity), pharynx (throat), and larynx.

Primary Functions:

- Air Conditioning: Crucial for cleaning, warming, and humidifying inhaled air before it reaches the delicate lower airways and lungs.

- Olfaction (Smell): Specialized receptors in the nasal cavity detect odors.

- Resonance for Speech: The nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses act as resonating chambers for the voice.

- Protection: Filters out airborne particles and pathogens.

- Aesthetics: The external nose significantly contributes to facial appearance.

- Weight Reduction of Skull: The air-filled paranasal sinuses lighten the skull.

Lower Respiratory Tract (LRT)

Extends from the trachea (windpipe) down to the alveoli (air sacs) within the lungs. Includes the trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, and lungs (which contain respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveoli).

Primary Functions:

- Air Conduction: Structures like the trachea and bronchi act as passageways for air.

- Gas Exchange (Respiration): The respiratory bronchioles and, most importantly, the alveoli are the primary sites where oxygen enters the blood and carbon dioxide leaves it.

Some classifications might place the larynx, its lower part (below the vocal cords) as part of the LRT from a functional airway perspective. However, anatomically, it's consistently taught as the lowest structure of the URT.

Upper Respiratory Tract

The upper respiratory tract (URT) comprises the nose, nasal cavity, sinuses, pharynx, and larynx, acting as the primary entry point for air, which it filters, warms, and humidifies.

The Nose

The nose is the most prominent anterior structure of the face, serving multiple vital roles.

Functions of the Nose:

- Olfaction (Smell): Houses olfactory receptors.

- Respiration: Provides the primary entry point for air into the respiratory system.

- Air Conditioning: Cleans, warms, and humidifies inspired air.

- Voice Resonance: Contributes to the timbre of the voice.

- Aesthetics: A key determinant of facial appearance.

Divisions: The nose is divided into the external nose and the nasal cavity.

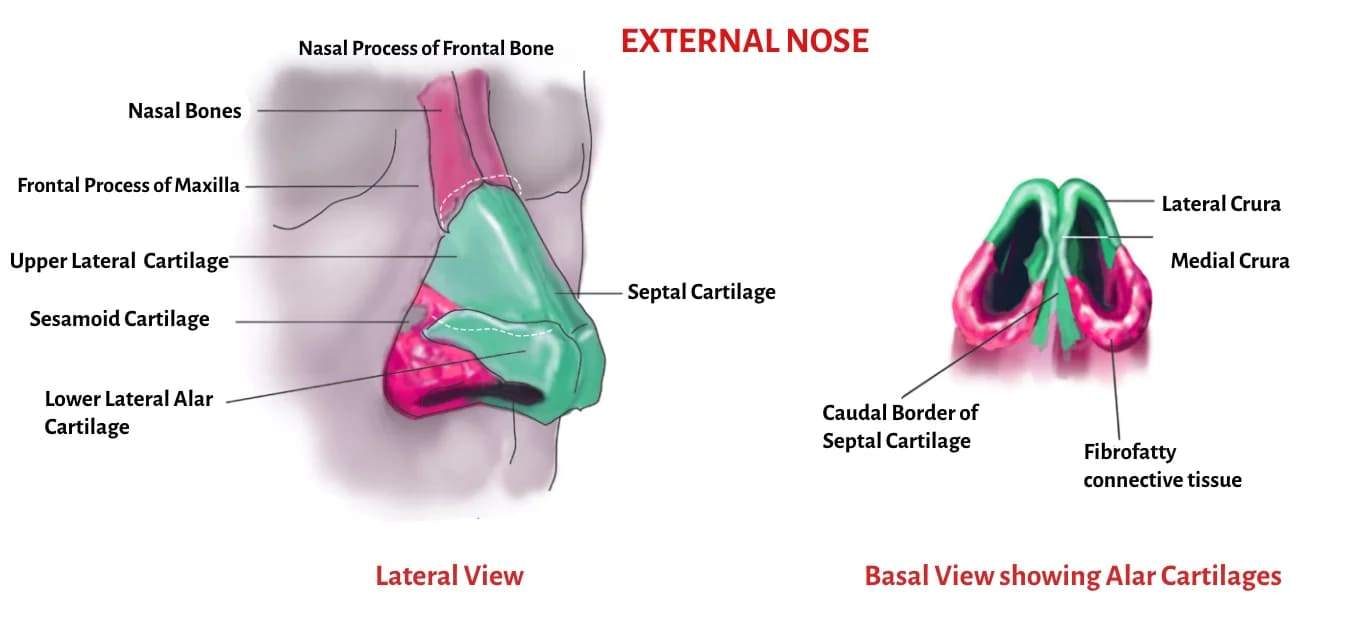

External Nose

This is the visible part of the nose, projecting from the face. Its shape and size vary significantly among individuals due to genetics, sex, and ethnicity.

Key Features:

- Root: The superior attachment of the nose to the forehead.

- Bridge: The superior, bony part of the nose.

- Dorsum Nasi: The anterior border from the root to the apex.

- Apex (Tip): The free, rounded end of the nose.

- Nares (Nostrils): The two external openings of the nasal cavity, separated by the nasal septum.

- Alae Nasi: The flared, cartilaginous expansions that form the lateral boundaries of the nares.

Framework of the External Nose

The external nose is supported by a combination of bone and hyaline cartilage.

Bony Framework (Superior Part - "Bridge"):

- Nasal Bones (paired): Form the superior part of the bridge.

- Frontal Processes of Maxillae (paired): Extend upwards along the sides of the nasal bones.

- Nasal Part of Frontal Bone: Forms the root of the nose.

Cartilaginous Framework (Inferior Part - "Apex and Alae"):

These are plates of hyaline cartilage that provide flexibility and shape.

- Septal Nasal Cartilage: Forms the anterior part of the nasal septum, extending from the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone and vomer, maintaining the midline structure.

- Lateral Nasal Cartilages (paired): Located superior to the major alar cartilages, contributing to the side walls of the nose.

- Major Alar Cartilages (paired): Form the apex and alae of the nose. Each has:

- Medial Crus: Forms part of the mobile nasal septum.

- Lateral Crus: Forms the ala of the nose.

- Minor Alar Cartilages (variable): Small, accessory cartilages within the alae.

- Alar Fibrofatty Tissue: Connective tissue and fat that contribute to the shape and flexibility of the alae, especially in the most inferior part.

Summary of Support:

- Bones: Support the upper one-third (bridge).

- Upper Cartilages (Lateral Nasal): Support the sides of the mid-nose.

- Lower Cartilages (Major Alar): Primarily support the tip and help define the shape and patency of the nostrils.

- Skin and connective tissue: Also contribute to the overall shape and covering.

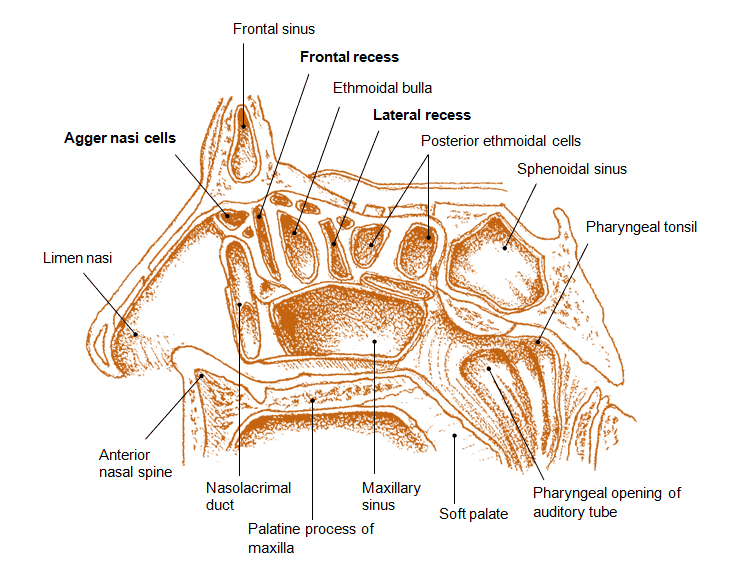

Nasal Cavity

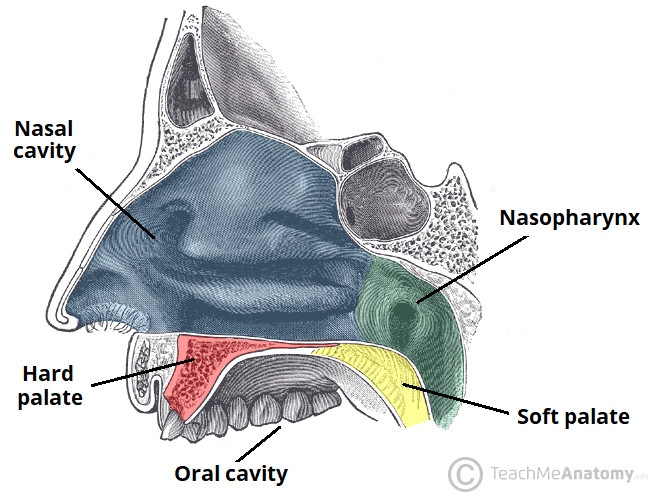

The nasal cavity is the internal space within the external nose, extending posterior to the pharynx.

Boundaries:

- Anteriorly: Communicates with the exterior via the nares (nostrils).

- Posteriorly: Opens into the nasopharynx via the choanae (posterior nasal apertures).

Walls of the Nasal Cavity:

Floor: Formed primarily by the hard palate (maxilla and palatine bones) and, to a lesser extent, the anterior part of the soft palate. This separates the nasal cavity from the oral cavity.

Roof: Narrow and arched, composed of several bones:

- Nasal Bone: Anteriorly.

- Frontal Bone: Anteriorly, between the nasal bones and ethmoid.

- Cribriform Plate of Ethmoid Bone: Mid-portion, perforated by olfactory nerve filaments. This is a critical anatomical landmark as it is thin and can be damaged.

- Body of Sphenoid Bone: Posteriorly.

Medial Wall (Nasal Septum): Divides the nasal cavity into right and left halves. It has both bony and cartilaginous components:

- Bony Parts:

- Perpendicular Plate of Ethmoid Bone: Forms the superior posterior part.

- Vomer: Forms the inferior posterior part.

- Cartilaginous Part:

- Septal Nasal Cartilage: Forms the anterior superior part, making up a significant portion of the septum.

- (Add: "Vomeronasal cartilage" is often a historical or minor finding; focus on the main three components for clarity.)

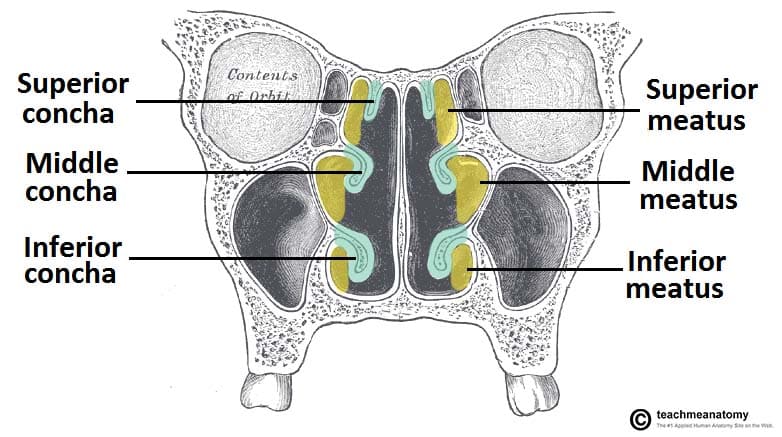

Lateral Wall: Complex and irregular, characterized by three shelf-like bony projections:

- Superior Nasal Concha (Turbinate): Part of the ethmoid bone.

- Middle Nasal Concha (Turbinate): Part of the ethmoid bone.

- Inferior Nasal Concha (Turbinate): A separate bone, not part of the ethmoid. These conchae increase the surface area of the nasal cavity and create turbulent airflow, facilitating air conditioning.

Nasal Meatus (Air Passages):

These are the spaces inferior to each concha.

- Spheno-ethmoidal Recess:

- Location: A small area located postero-superior to the superior nasal concha.

- Opening: Receives the opening of the sphenoidal air sinus.

- Superior Meatus:

- Location: Lies inferior to the superior nasal concha.

- Opening: Receives the opening of the posterior ethmoidal air cells (part of the ethmoid sinus).

- Middle Meatus: This is the most complex and clinically important meatus.

- Location: Lies inferior to the middle nasal concha.

- Key Structures:

- Bulla Ethmoidalis: A prominent bulge on the lateral wall, formed by the expansion of the middle ethmoidal air cells, which open onto or near it.

- Hiatus Semilunaris: A curved, crescent-shaped groove located inferior to the bulla ethmoidalis.

- Ethmoidal Infundibulum: A funnel-shaped channel that extends anteriorly and superiorly from the hiatus semilunaris.

- Openings: The hiatus semilunaris (or directly into the infundibulum) receives the drainage from: Maxillary Sinus, Frontal Sinus, & Anterior Ethmoidal Air Cells.

- Inferior Meatus:

- Location: Lies inferior to the inferior nasal concha.

- Opening: Receives the opening of the nasolacrimal duct, which drains tears from the eye into the nasal cavity.

Clinical Significance: The complex arrangement of conchae and meatuses, particularly the middle meatus, is crucial for understanding sinus drainage and the pathology of sinusitis. Blockage of these openings can lead to infection.

The Palate

The palate forms the roof of the oral cavity and the floor of the nasal cavity, acting as a crucial separator between these two spaces.

Divisions:

Hard Palate (Anterior 2/3):

Bony and immovable.

- Composition: Formed by the horizontal plates of the palatine bones posteriorly and the palatine processes of the maxillae anteriorly. (The term "premaxilla" is often used in developmental contexts for the anterior part of the maxilla forming the primary palate).

- Boundaries: Bounded anteriorly and laterally by the alveolar processes containing the teeth and their associated gingivae (gums).

- Covering: Covered by a thick, keratinized mucous membrane that is firmly attached to the underlying periosteum, making it resilient.

- Continuity: Continuous posteriorly with the soft palate.

Soft Palate (Posterior 1/3):

Fibromuscular and highly mobile. Lacks any bony support.

- Attachments: Attached to the posterior edge of the hard palate.

- Muscles: Contains several muscles that allow for its movement during swallowing, gag reflex, and speech.

- Uvula: A conical, fleshy projection hanging from the free posterior border of the soft palate.

- Functions:

- Swallowing (Deglutition): During swallowing, the soft palate and uvula elevate to close off the nasopharynx, preventing food and liquids from entering the nasal cavity.

- Speech: Modifies the resonance of speech sounds.

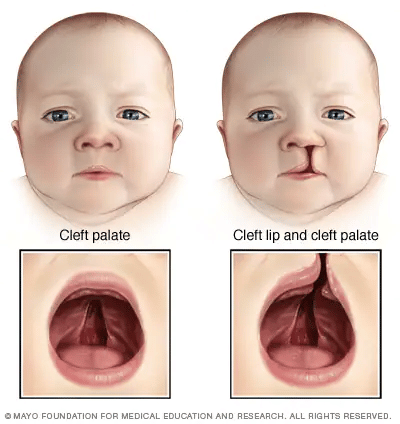

A congenital malformation where there is an incomplete fusion of the palatine processes during embryonic development, resulting in an abnormal opening (communication) between the oral and nasal cavities.

Types: Can affect the hard palate, soft palate, or both. Often co-occurs with cleft lip.

Etiology (Causes): Multifactorial, involving both genetic predisposition and environmental factors. Risk factors include:

- Maternal Factors: Advanced maternal age, certain anticonvulsant medications during pregnancy, smoking, alcohol consumption, folate deficiency.

- Genetic Factors: Family history of clefting.

- Sex: Slightly more common in females (though cleft lip +/- palate is more common in males).

- Feeding Difficulties: Infants struggle with creating suction for feeding, leading to poor nutrition and potential aspiration.

- Speech Impairment: Difficulty forming certain sounds due to air escaping through the nose.

- Ear Infections: Increased risk of otitis media due to dysfunction of the Eustachian tube.

- Dental Problems: Misalignment of teeth.

- Psychological/Social: Affects aesthetics and can lead to self-consciousness.

- Respiratory Tract Infections (RTIs): Due to chronic oral breathing and potential for aspiration.

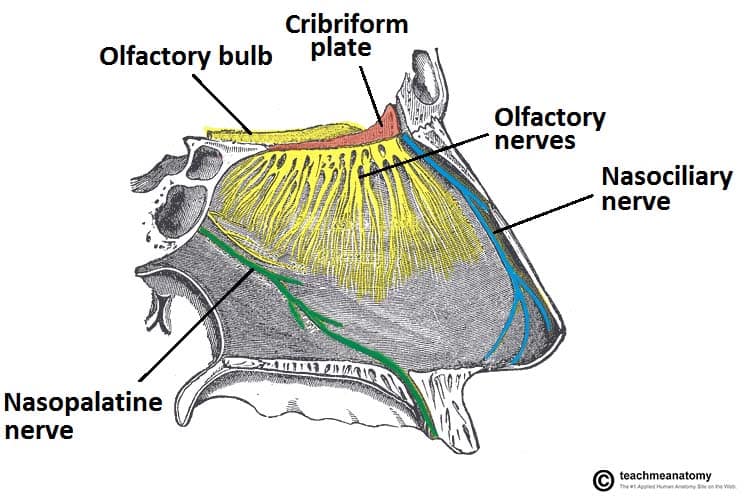

The nasal cavity is lined by two distinct types of mucous membrane, each with specialized functions:

Olfactory Mucous Membrane (Olfactory Epithelium):

The olfactory mucous membrane (olfactory mucosa) is a specialized, yellowish-brown tissue lining the roof of the nasal cavity, superior conchae, and upper nasal septum. It contains bipolar receptor neurons that detect odors, along with supporting cells and glands, facilitating the sense of smell and serving as a barrier against pathogens.

- Location: Limited to the superior part of the nasal cavity, specifically covering:

- The superior nasal concha.

- The superior part of the nasal septum.

- The roof of the nasal cavity (cribriform plate area) and the spheno-ethmoidal recess itself

- Composition: Contains specialized olfactory receptor neurons (bipolar neurons).

- Function: Responsible for the sense of smell (olfaction).

- Pathway of Olfaction: Olfactory receptor neurons detect chemical odors. Their axons (fila olfactoria) pass superiorly through the small perforations (foramina) in the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone to synapse with neurons in the olfactory bulb, which is part of the central nervous system located in the anterior cranial fossa.

Respiratory Mucous Membrane (Respiratory Epithelium):

Respiratory epithelium is a specialized ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium lining most of the conducting airways (nasal cavity, trachea, bronchi). It acts as a protective barrier, using mucus from goblet cells and mucociliary clearance to trap and expel pathogens/debris. It warms, humidifies, and filters inhaled air.

- Location: Lines the vast majority of the nasal cavity, covering all areas not occupied by the olfactory epithelium (i.e., inferior to the superior concha and olfactory region).

- Composition: Characterized by pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium with goblet cells (PCC with GC).

- Functions: Critically important for air conditioning:

- Warming Air: A rich vascular plexus (especially a dense network of veins known as the venous cavernous plexus or Kiesselbach's plexus in the submucosa) warms incoming air.

- Moistening Air: Seromucous glands and abundant goblet cells produce mucus, which adds moisture to the inhaled air.

- Cleaning Air: The sticky mucus traps airborne particles, dust, and pathogens. The cilia on the epithelial cells rhythmically beat, sweeping the contaminated mucus posteriorly towards the nasopharynx, where it is typically swallowed and destroyed by stomach acid. This is known as the mucociliary escalator.

Nerve Supply of the Nasal Cavity

The nasal cavity receives two main types of innervation: The nasal cavity receives sensory input from the olfactory nerve (CN I) for smell, and general sensation (pain, temperature, touch) from the trigeminal nerve (V1 and V2). Autonomic innervation controls mucosa blood flow and secretion via sympathetic (vasoconstriction) and parasympathetic (secretion) fibers.

Special Sensory (Olfaction): Olfactory Nerves (Cranial Nerve I): Responsible for the sense of smell. These fine nerve filaments arise from the olfactory epithelium, pass through the cribriform plate, and synapse in the olfactory bulb.

General Sensation:

- Provides touch, pain, and temperature sensation. Derived from branches of the Trigeminal Nerve (Cranial Nerve V).

- Ophthalmic Division (CN V1) through the Nasociliary Nerve:

- Anterior Ethmoidal Nerve: Supplies the anterior-superior part of the nasal septum and lateral wall, as well as the external nose.

- Posterior Ethmoidal Nerve: (Often overlooked but important) Supplies a small superior posterior part.

- Maxillary Division (CN V2) through the Pterygopalatine Ganglion: This ganglion receives fibers from CN V2 and provides a complex distribution of nerves to the posterior nasal cavity.

- Nasopalatine Nerve: Descends along the nasal septum, supplying the posterior-inferior part of the septum and eventually entering the incisive canal to supply the anterior hard palate.

- Posterior Superior Lateral Nasal Branches: Supply the posterior superior part of the lateral nasal wall and superior and middle conchae.

- Posterior Inferior Lateral Nasal Branches: Supply the posterior inferior part of the lateral nasal wall and inferior concha.

- (Note: The term "nasal" and "palatine" branches from the pterygopalatine ganglion are correct but more precisely broken down as above.)

Autonomic Innervation:

- Parasympathetic Fibers: Originate from the facial nerve (CN VII), travel via the greater petrosal nerve to the pterygopalatine ganglion. Postganglionic fibers then distribute with CN V2 branches to the nasal glands, causing vasodilation and increased mucous secretion (e.g., rhinorrhea).

- Sympathetic Fibers: Originate from the superior cervical ganglion. Postganglionic fibers also reach the pterygopalatine ganglion but pass through it without synapsing. They then distribute to nasal blood vessels, causing vasoconstriction (e.g., in response to cold or decongestants).

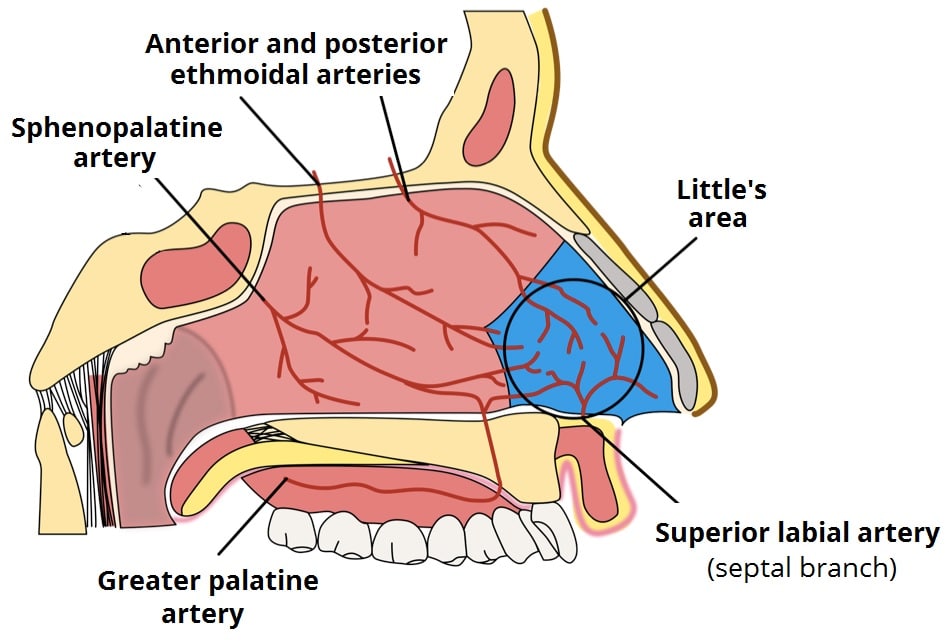

Blood Supply of the Nasal Cavity

The nasal cavity has a very rich and anastomosing blood supply, which is essential for warming air but also makes it prone to bleeding (epistaxis).

Arterial Supply: Primarily from branches of the Internal Carotid Artery and the External Carotid Artery.

From the Ophthalmic Artery (a branch of the Internal Carotid Artery):

- Anterior Ethmoidal Artery: Supplies the anterior-superior part of the lateral wall and septum.

- Posterior Ethmoidal Artery: Supplies the posterior-superior part of the lateral wall and septum.

From the Maxillary Artery (a terminal branch of the External Carotid Artery):

- Sphenopalatine Artery: This is the major arterial supply to the nasal cavity. It enters through the sphenopalatine foramen and branches extensively to supply the posterior-inferior part of the lateral wall and septum. It is often called the "artery of epistaxis."

- Greater Palatine Artery: Contributes some supply to the posterior inferior septum.

From the Facial Artery (a branch of the External Carotid Artery):

- Superior Labial Artery: Gives off a septal branch that contributes to the supply of the anterior part of the septum.

Location: A highly vascularized area on the anterior-inferior part of the nasal septum.

Composition: It's an anastomotic plexus formed by the convergence of branches from all five major arteries supplying the nasal septum:

- Anterior Ethmoidal Artery

- Posterior Ethmoidal Artery

- Sphenopalatine Artery

- Greater Palatine Artery

- Superior Labial Artery

Venous Drainage:

- Veins generally accompany the arteries and form a rich submucosal venous plexus.

- Blood drains posteriorly into the sphenopalatine vein (which leads to the pterygoid venous plexus) and anteriorly into the facial vein.

- Ethmoidal veins drain into the ophthalmic veins.

- Clinical note: Connections to the cavernous sinus via ophthalmic veins are important, as infections in the nasal cavity can potentially spread intracranially.

Lymphatic Drainage of the Nasal Cavity

The lymphatic drainage of the nasal cavity follows a pattern that reflects its anterior and posterior regions.

Anterior Nasal Cavity (including the Nasal Vestibule): Lymphatics drain into the submandibular lymph nodes.

Posterior Nasal Cavity (the larger part of the nasal cavity): Lymphatics drain primarily into the retropharyngeal lymph nodes (often then to deep cervical nodes) and the deep cervical lymph nodes (particularly the upper group).

- Clinical Significance: Understanding lymphatic drainage is for tracking the spread of infections or malignancies originating in the nasal cavity.

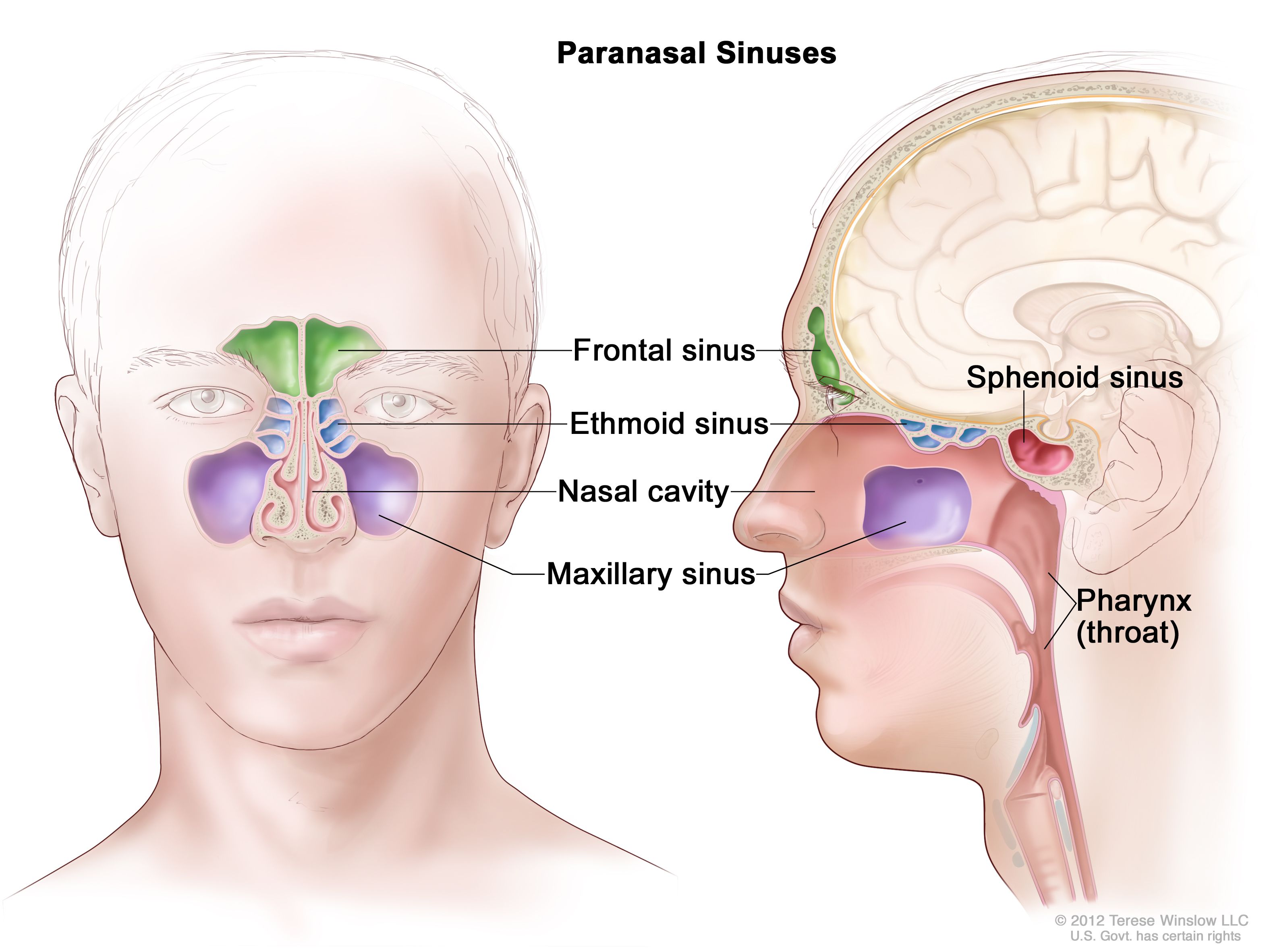

Paranasal Sinuses

The paranasal sinuses are air-filled, mucosa-lined extensions of the respiratory part of the nasal cavity that invaginate into four surrounding cranial bones: the frontal, ethmoid, sphenoid, and maxillary bones.

- Development: These sinuses begin to develop in fetal life but continue to expand (pneumatize) into the surrounding bones throughout childhood and even into adulthood. This expansion is more pronounced in older individuals.

- Lining: They are lined with mucoperiosteum, which is a specialized mucous membrane (respiratory epithelium: pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium with goblet cells) that is intimately adhered to the underlying periosteum of the bone. This continuity of the mucosal lining means that infections from the nasal cavity can easily spread to the sinuses.

Functions of Paranasal Sinuses

- Air Conditioning: The extensive mucosal lining contributes to the warming and humidifying of inspired air.

- Mucus Drainage (Mucociliary Clearance): The cilia on the columnar cells of the mucoperiosteum continuously beat, moving mucus (which traps particulate matter and pathogens) towards the openings (ostia) of the sinuses, from where it drains into the nasal cavity.

- Voice Resonance: They act as resonating chambers, influencing the timbre and quality of the voice. Blockage or fluid accumulation within the sinuses can significantly alter voice quality (e.g., a "nasal" or "muffled" sound).

- Lightening the Skull: Being air-filled spaces, they reduce the overall weight of the skull, which makes it easier for neck muscles to support the head.

- Protection: They may play a role in cranial protection by absorbing forces during facial trauma, acting as "crumple zones."

- Immune Defense: The mucus and immune cells within the mucosa contribute to local defense against pathogens.

Clinical Correlation: Sinusitis

Sinusitis is the inflammation and swelling of the mucoperiosteum lining one or more paranasal sinuses.

- Etiology: It commonly arises from infections (viral, bacterial, fungal) or allergic reactions that spread from the nasal cavities due to the continuous mucosal lining.

- Pathophysiology:

- Inflammation leads to mucosal swelling and increased mucus production.

- This swelling can easily block the narrow drainage ostia of the sinuses into the nasal cavity.

- Blockage leads to mucus accumulation, creating a favorable environment for bacterial growth and increasing pressure within the sinus.

- Symptoms:

- Local Pain: Often referred to the area over the affected sinus (e.g., forehead pain for frontal sinusitis, cheek pain for maxillary sinusitis).

- Pressure/Fullness: Due to accumulated fluid and inflammation.

- Tenderness: Over the affected sinus.

- Nasal Congestion and Discharge: Often purulent.

- Headache, Fever, Fatigue.

- Voice Change: Muffled quality.

- Pansinusitis: A severe form where multiple or all paranasal sinuses are inflamed.

- Complications: While usually benign, severe sinusitis can lead to orbital cellulitis (especially from ethmoid), osteomyelitis, or even intracranial complications due to the close proximity of the sinuses to the brain and orbit.

Frontal Sinuses

Location: Situated within the frontal bone, between its outer and inner cortical tables. They are typically found posterior to the superciliary arches (brow ridges) and the root of the nose.

Structure:

- Two sinuses, right and left, separated by a bony septum (which is rarely in the median plane).

- They are often asymmetrical and vary significantly in size and shape among individuals.

- Each sinus is roughly triangular.

Development: Begin to pneumatize during childhood and are radiographically detectable around 6-7 years of age, reaching full size in late adolescence.

Drainage: Each frontal sinus drains inferiorly through the frontonasal duct (or nasofrontal duct). This duct empties into the ethmoidal infundibulum, which in turn opens into the semilunar hiatus of the middle nasal meatus.

Innervation: Sensory innervation is primarily provided by branches of the supraorbital nerves, which are derived from the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (CN V1). This explains referred pain from frontal sinusitis to the forehead.

Variations of the Frontal Sinuses

- Asymmetry: The right and left frontal sinuses are rarely equal in size, and their separating septum is often deviated from the midline.

- Size: They can range from very small to extensively large, sometimes extending laterally into the greater wings of the sphenoid bone or superiorly towards the parietal bone.

- Compartmentalization: A frontal sinus may have two parts: a vertical component in the squamous part of the frontal bone and a horizontal component in the orbital part.

- Clinical Significance of Large Sinuses: When the orbital part is large, its roof forms part of the floor of the anterior cranial fossa, and its floor forms the roof of the orbit. This proximity is clinically important during surgery or in cases of severe infection.

Ethmoidal Sinuses (Ethmoidal Air Cells)

- Location: These are not single large sinuses but a collection of multiple, small, interconnected air cells located within the ethmoid bone. They lie between the nasal cavity medially and the orbit laterally.

- Development: Present at birth but continue to grow. They are generally not well visualized on plain radiographs before 2 years of age but are readily identifiable on CT scans.

- Grouping and Drainage: They are typically divided into three main groups based on their drainage patterns:

- Anterior Ethmoidal Cells:

- Drainage: Drain directly or indirectly into the ethmoidal infundibulum, which then opens into the middle nasal meatus (via the semilunar hiatus).

- Middle Ethmoidal Cells:

- Drainage: Typically open directly onto the middle nasal meatus, often forming the prominent bulge known as the bulla ethmoidalis on the superior border of the semilunar hiatus.

- Posterior Ethmoidal Cells:

- Drainage: Open directly into the superior nasal meatus.

- Anterior Ethmoidal Cells:

- Innervation: Sensory innervation is provided by the anterior and posterior ethmoidal branches of the nasociliary nerve (a branch of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, CN V1).

Vulnerability: The ethmoidal cells have thin bony walls, especially medially (lamina papyracea of the orbit) and superiorly (cribriform plate).

Spread of Infection:

- Orbital Complications: Infections can easily erode through the fragile medial wall of the orbit, leading to serious complications such as orbital cellulitis or even orbital abscess.

- Visual Impairment: Some posterior ethmoidal cells are in close proximity to the optic canal, which transmits the optic nerve (CN II) and ophthalmic artery. Spread of infection or inflammation here can compress the optic nerve, potentially causing optic neuritis or even blindness.

- Intracranial Spread: Infection can also spread superiorly through the cribriform plate to the anterior cranial fossa, leading to meningitis or brain abscess, though this is less common than orbital spread.

Sphenoid Sinuses

- Location: Situated within the body of the sphenoid bone, often extending into its greater wings and pterygoid processes.

- Development: They begin to pneumatize around 2-3 years of age, often originating from a posterior ethmoidal cell that invades the sphenoid bone. They are fully developed by late adolescence.

- Structure:

- Usually two sinuses, separated by a bony septum, which is frequently asymmetrical.

- The extensive pneumatization makes the body of the sphenoid bone relatively thin and fragile.

- Drainage: Each sphenoid sinus drains into the spheno-ethmoidal recess, which is located superior and posterior to the superior nasal concha.

- Innervation: Sensory innervation is primarily from the posterior ethmoidal nerve (a branch of the ophthalmic division of CN V1) and branches from the maxillary nerve (CN V2) (specifically, the pharyngeal branch).

- Arterial Supply: Primarily by the posterior ethmoidal arteries and branches from the maxillary artery.

The thin walls of the sphenoid sinuses place them in close proximity to numerous critical neurovascular structures, making sphenoid sinusitis or trauma particularly dangerous:

- Superiorly:

- Optic Nerves (CN II) and Optic Chiasm: Inflammation or infection can affect vision.

- Pituitary Gland: Located in the sella turcica, directly superior to the sinus. This proximity allows for a transsphenoidal surgical approach to the pituitary gland, minimizing external incisions.

- Laterally:

- Cavernous Sinuses: Containing important cranial nerves (III, IV, V1, V2, VI) and the internal carotid artery. Infection can lead to cavernous sinus thrombosis.

- Internal Carotid Arteries: Run in grooves along the lateral walls of the sinus.

- Inferiorly: The nasopharynx.

Maxillary Sinuses (Antra of Highmore)

- Location: The largest of the paranasal sinuses, occupying the body of the maxilla.

- Shape: Roughly pyramidal.

- Boundaries:

- Apex: Extends laterally towards the zygomatic bone.

- Base: Forms the inferolateral wall of the nasal cavity.

- Roof: Forms the floor of the orbit.

- Floor: Formed by the alveolar process of the maxilla, making it closely related to the roots of the posterior maxillary teeth (premolars and molars).

- Development: Present at birth as a small furrow and rapidly grows. It reaches full size around 15 years of age.

- Drainage: Each maxillary sinus drains through one or more small openings, the maxillary ostium (or ostia). Crucially, this ostium is located high on the medial wall of the sinus, near the roof, making drainage against gravity difficult. It opens into the semilunar hiatus of the middle nasal meatus.

- Arterial Supply:

- Mainly from the superior alveolar branches of the maxillary artery.

- The floor also receives contributions from branches of the descending palatine artery (including the greater palatine artery).

- Innervation: Sensory innervation is provided by the anterior, middle, and posterior superior alveolar nerves, all of which are branches of the maxillary nerve (CN V2).

- Drainage Issues: The high location of the maxillary ostium makes it prone to poor drainage, especially when inflamed and swollen, predisposing it to infection.

- Dental Relationship: The close proximity of the roots of the maxillary molars and premolars to the floor of the sinus means that:

- Dental infections (e.g., abscesses) can easily spread to the maxillary sinus, causing sinusitis of dental origin.

- Tooth extractions can sometimes create an oroantral fistula (a communication between the oral cavity and the maxillary sinus).

- Pain from maxillary sinusitis can be referred to the maxillary teeth, and vice versa.

- Trauma: Due to its size and location, the maxillary sinus is commonly involved in facial fractures.

Summary Table: Paranasal Sinuses

| Sinus | Location | Drainage (into Nasal Cavity) | Innervation (Sensory) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frontal | Within the frontal bone, posterior to the superciliary arches. | Middle Meatus (via the frontonasal duct into the ethmoidal infundibulum). | Supraorbital nerves (CN V₁ - Ophthalmic division). |

| Maxillary | Within the body of the maxilla; roof is the orbital floor; floor is the alveolar process. | Middle Meatus (via the maxillary ostium and semilunar hiatus). | Superior Alveolar nerves (Anterior, Middle, Posterior) (CN V₂ - Maxillary division). |

| Ethmoidal (Anterior) | Within the ethmoid bone (anterior cells). | Middle Meatus (via the ethmoidal infundibulum). | Anterior ethmoidal nerve (CN V₁ - Ophthalmic division). |

| Ethmoidal (Middle) | Within the ethmoid bone (middle cells / ethmoidal bulla). | Middle Meatus (directly onto the ethmoidal bulla). | Anterior ethmoidal nerve (CN V₁ - Ophthalmic division). |

| Ethmoidal (Posterior) | Within the ethmoid bone (posterior cells). | Superior Meatus. | Posterior ethmoidal nerve (CN V₁ - Ophthalmic division). |

| Sphenoid | Within the body of the sphenoid bone (may extend into the wings). | Spheno-ethmoidal recess (postero-superior to superior concha). | Posterior ethmoidal nerve (CN V₁) and branches of Maxillary nerve (CN V₂). |

Embryology of the Nose

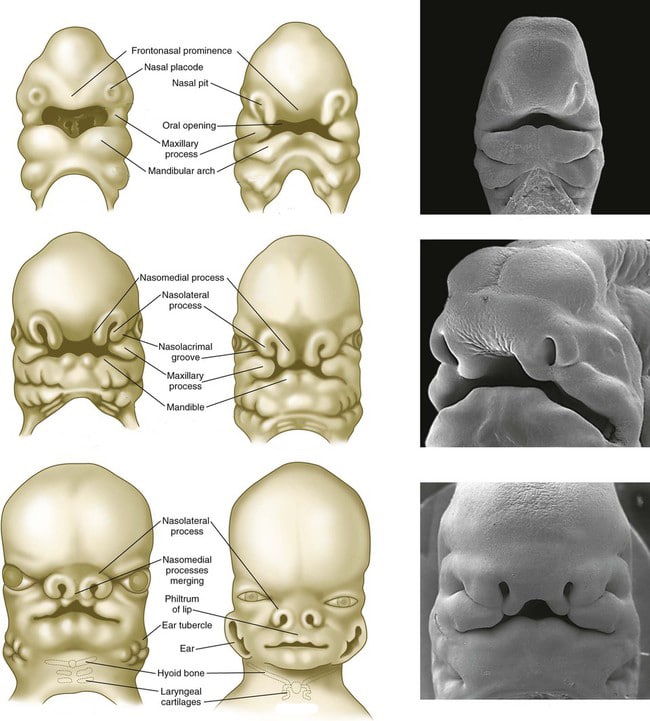

The human nose develops between the 4th and 10th week of gestation from five facial prominences (one frontonasal, paired maxillary, paired mandibular) stimulated by neural crest cells.

The development of the nose originates from ectoderm and surrounding mesenchyme.

- Week 4:

- Nasal Placodes: Bilateral thickenings of surface ectoderm, called nasal placodes, appear on the frontonasal prominence.

- Nasal Pits: These placodes soon invaginate to form nasal pits, which are the primordia of the anterior nares and nasal cavities.

- Nasal Processes: The pits are surrounded by elevated ridges of mesenchyme: the medial nasal processes (medially) and the lateral nasal processes (laterally).

- Weeks 5-6:

- Nasal Sacs: The nasal pits deepen significantly to form nasal sacs.

- Intermaxillary Segment Formation: The two medial nasal processes fuse in the midline. Simultaneously, these medial nasal processes also fuse with the maxillary processes (derived from the first pharyngeal arch) on either side. This fusion creates the intermaxillary segment, a crucial structure that gives rise to:

- The philtrum of the upper lip.

- The primary palate (the anterior part of the hard palate, anterior to the incisive foramen).

- The part of the nasal septum derived from the frontonasal prominence.

- Week 7:

- Oronasal Membrane Rupture: The nasal sacs are initially separated from the primitive oral cavity by the oronasal membrane. This membrane ruptures by the 7th week, establishing a connection between the nasal cavity and the oral cavity. The openings formed are called the primitive choanae.

- Weeks 7-8 (Persistence until Week 17):

- Epithelial Plug: The developing anterior nares (nostrils) temporarily become occluded by an epithelial plug. This plug typically dissolves via programmed cell death (apoptosis) by the 17th week, re-establishing patent nasal passages.

- Week 10 Onward:

- Cartilage and Bone Differentiation: The mesenchyme surrounding the developing nasal cavities begins to differentiate. A cartilaginous nasal capsule forms, providing the initial framework for structures like the nasal septum and the ethmoid bones. This cartilage later ossifies or remains as permanent cartilage.

Week 4 (Initiation): Ectodermal thickenings (nasal placodes) appear on the frontonasal process.

Week 5 (Pit Formation): Nasal placodes invaginate to form nasal pits, which are surrounded by medial and lateral nasal processes.

Week 6 (Fusion): The maxillary prominences grow towards the midline, forcing the medial nasal processes to fuse, creating the nasal septum, bridge, and philtrum.

Weeks 6–7 (Choanae Formation): The oronasal membrane ruptures, creating a communication between the nasal sacs and the oral cavity (primitive choanae).

Weeks 7–16 (Nasal Plugs): Epithelial plugs temporarily seal the nostrils, reopening by the 16th week.

Development of Sinuses: Paranasal sinuses begin as diverticula of the nasal cavity: the ethmoid sinuses develop first (week 4-birth), followed by the maxilla (week 10) and sphenoid (month 3).

Congenital Anomalies

- Cleft Lip and Palate: Result from incomplete fusion of facial processes, particularly the maxillary processes with the medial nasal processes (for cleft lip and primary palate) and the palatal shelves (for secondary palate).

- Choanal Atresia: This is a key anomaly directly related to the developmental timeline. It occurs when the oronasal membrane fails to rupture or, more commonly, due to a persistence of bony or membranous tissue at the posterior choanae.

- Unilateral: Often asymptomatic or presents with unilateral nasal discharge.

- Bilateral: A life-threatening emergency in neonates, as they are obligate nasal breathers. It presents with cyclical cyanosis (worse with feeding, improves with crying) and respiratory distress.

- Nasal Agenesis/Hypoplasia: Complete absence or underdevelopment of the nose.

- Nasal Cysts and Sinuses: Result from incomplete obliteration of embryonic structures or persistence of epithelial rests.

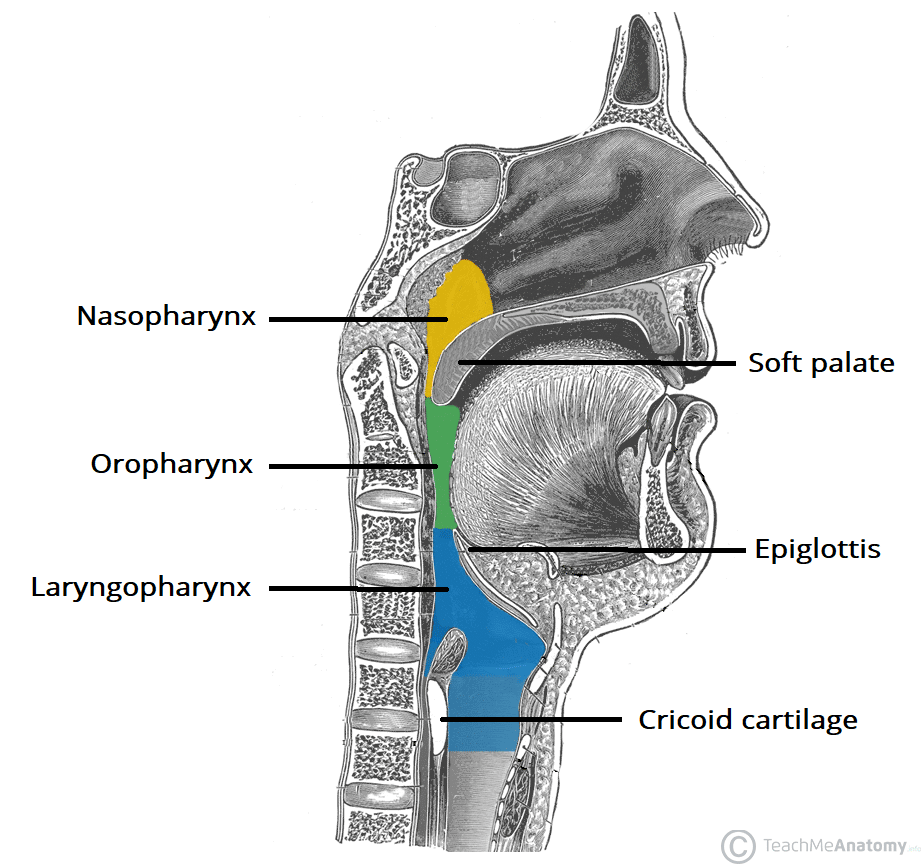

II. Pharynx

The pharynx is a muscular tube extending from the base of the skull to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage (C6 vertebra), where it becomes continuous with the esophagus.

- Location: Situated posterior to the nasal cavity, oral cavity, and larynx.

- Function: It serves as a common pathway for both air (respiratory tract) and food/fluids (digestive tract).

- Divisions: For anatomical and functional convenience, it is divided into three parts:

- Nasopharynx: Posterior to the nasal cavity. Primarily respiratory.

- Oropharynx: Posterior to the oral cavity. Both respiratory and digestive.

- Laryngopharynx (Hypopharynx): Posterior to the larynx. Both respiratory and digestive.

- Walls/Layers: The pharyngeal wall consists of three main layers:

- Mucosa: Lined by different epithelia in its divisions (respiratory in nasopharynx, stratified squamous in oropharynx/laryngopharynx).

- Fibrous Layer (Pharyngobasilar Fascia): Provides structural support and attachment to the skull base.

- Muscular Layer: Composed of an outer layer of three constrictor muscles (superior, middle, inferior) and an inner layer of three longitudinal muscles (stylopharyngeus, salpingopharyngeus, palatopharyngeus).

- Clinical Significance: Retropharyngeal Space: The pharynx is bounded posteriorly by the retropharyngeal space, a potential space anterior to the prevertebral fascia. This space is a crucial clinical consideration because it acts as a conduit for infections from the pharynx or oral cavity to spread inferiorly into the posterior mediastinum, leading to serious complications.

Nasopharynx

The nasopharynx is the most superior part of the pharynx, located posterior to the nasal cavity and superior to the soft palate. It is exclusively a respiratory passage.

Boundaries:

- Superiorly (Roof): Formed by the body of the sphenoid bone and the basilar part of the occipital bone. Contains the pharyngeal tonsil (adenoids).

- Inferiorly: Open communication with the oropharynx, marked by the free border of the soft palate and the pharyngeal isthmus (which can be closed by the soft palate during swallowing).

- Anteriorly: Communicates with the nasal cavity through the choanae.

- Posteriorly: Related to the C1 (atlas) vertebra. Contains the pharyngeal tonsil.

- Lateral Walls: Feature the opening of the pharyngotympanic (Eustachian) tube, which connects the nasopharynx to the middle ear, allowing for pressure equalization. The torus tubarius is an elevation formed by the cartilaginous part of the tube. The pharyngeal recess (fossa of Rosenmüller) is a deep depression posterior to the torus tubarius.

Lining: Lined with pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (respiratory epithelium), similar to the nasal cavity.

Lymphoid Tissue: Contains the pharyngeal tonsil (adenoids) in its roof and posterior wall, which is part of Waldeyer's ring of lymphoid tissue. Enlarged adenoids can obstruct nasal breathing, Eustachian tube function, and affect voice.

III. Larynx

The larynx, commonly known as the "voice box," is a complex cartilaginous structure located in the anterior neck, extending from the level of the C3 to C6 vertebrae. It connects the pharynx superiorly with the trachea inferiorly.

- Functions:

- Airway Patency: Maintains an open air passage.

- Protection of Lower Airway: Acts as a sphincter to prevent food and liquids from entering the trachea during swallowing (primary function of the epiglottis and vocal folds).

- Phonation (Voice Production): Houses the vocal folds, which vibrate to produce sound.

- Structure: Composed of nine cartilages (three single, three paired), connected by various membranes and ligaments, and moved by both extrinsic and intrinsic muscles.

Cartilages of the Larynx

There are nine laryngeal cartilages:

A. Single Cartilages (3)

- Thyroid Cartilage: The largest laryngeal cartilage, forming the anterior and lateral walls.

- Composed of two laminae that fuse anteriorly to form the laryngeal prominence (Adam's apple), which is more prominent in males.

- Made of hyaline cartilage.

- Cricoid Cartilage: The only complete ring of cartilage in the larynx, shaped like a signet ring (narrow anteriorly, broad lamina posteriorly).

- Located inferior to the thyroid cartilage and superior to the trachea.

- Made of hyaline cartilage.

- Epiglottic Cartilage (Epiglottis): A leaf-shaped, elastic cartilage located posterior to the root of the tongue and hyoid bone.

- Its superior free margin projects posterosuperiorly, while its inferior stalk attaches to the thyroid cartilage.

- Acts as a "lid", bending posteriorly during swallowing to cover the laryngeal inlet and direct food into the esophagus.

- Made of elastic fibrocartilage.

B. Paired Cartilages (3 pairs, 6 total)

- Arytenoid Cartilages:

- Small, pyramidal cartilages that articulate with the superior border of the cricoid lamina.

- Crucial for voice production as the vocal ligaments attach to their vocal processes, and laryngeal muscles attach to their muscular processes.

- Made of hyaline cartilage.

- Corniculate Cartilages:

- Small, cone-shaped cartilages that articulate with the apices of the arytenoid cartilages.

- Made of elastic fibrocartilage.

- Cuneiform Cartilages:

- Small, rod-shaped cartilages embedded in the aryepiglottic folds. They do not articulate with other cartilages.

- Provide support to the aryepiglottic folds.

- Made of elastic fibrocartilage.

C. Cartilage Composition

- Hyaline Cartilage: Thyroid, Cricoid, and Arytenoid cartilages. These can calcify and ossify with age, making them visible on X-rays and more brittle.

- Elastic Fibrocartilage: Epiglottic, Corniculate, and Cuneiform cartilages. These remain flexible throughout life and do not ossify.

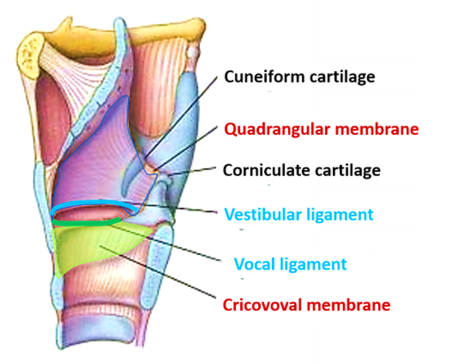

Ligaments and Membranes of the Larynx

Laryngeal cartilages are interconnected by various ligaments and membranes, which are classified as extrinsic (connecting larynx to other structures) or intrinsic (connecting parts of the larynx itself).

A. Extrinsic Ligaments and Membranes (connect larynx to outside structures)

- Thyrohyoid Membrane:

- Connects: Superior border of the thyroid cartilage to the superior aspect of the hyoid bone.

- Features: It is pierced on each side by the internal laryngeal nerve (a branch of the superior laryngeal nerve) and the superior laryngeal artery and vein. It also forms the lateral boundaries of the piriform fossae.

- Thickenings:

- Median Thyrohyoid Ligament: Central thickening.

- Lateral Thyrohyoid Ligaments: Posterior thickenings, often containing a small cartilaginous nodule (triticeal cartilage).

- Cricotracheal Ligament (Membrane):

- Connects: Inferior border of the cricoid cartilage to the first tracheal ring.

- Hyoepiglottic Ligament:

- Connects: Anterior surface of the epiglottis to the body of the hyoid bone.

- Thyroepiglottic Ligament:

- Connects: Stalk of the epiglottis to the inner aspect of the thyroid cartilage (just inferior to the thyroid notch).

B. Intrinsic Ligaments and Membranes (connect parts of the larynx)

These structures form the walls and folds within the larynx.

- Cricothyroid Ligament (Conus Elasticus):

- Structure: A strong elastic membrane connecting the cricoid cartilage to the thyroid cartilage. Its superior free border forms the vocal ligament (true vocal cord).

- Location: Extends from the superior border of the cricoid arch to the vocal process of the arytenoid and the inner surface of the thyroid cartilage.

- Clinical Significance: This membrane is the site for an emergency airway procedure called cricothyrotomy.

- Quadrangular Membrane:

- Structure: A broad, thin sheet of connective tissue extending from the lateral border of the epiglottis and the thyroid cartilage to the arytenoid cartilages.

- Borders:

- Upper free border: Forms the aryepiglottic folds, which define the lateral margins of the laryngeal inlet.

- Lower free border: Forms the vestibular ligament (or false vocal cord), which is covered by mucosa to form the vestibular fold.

Summary of Folds:

- Vocal folds (true vocal cords): Formed by the vocal ligament (superior border of the cricothyroid ligament) covered by mucosa. These are responsible for phonation.

- Vestibular folds (false vocal cords): Formed by the vestibular ligament (inferior border of the quadrangular membrane) covered by mucosa. They protect the vocal folds and the airway but are not primarily involved in phonation.

- Aryepiglottic folds: Formed by the superior border of the quadrangular membrane, covered by mucosa. They enclose the cuneiform and corniculate cartilages and define the laryngeal inlet.

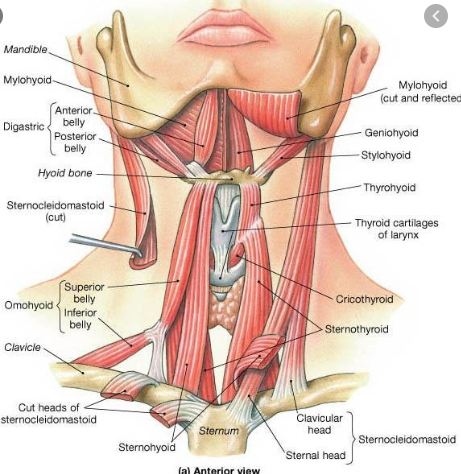

Muscles of the Larynx

The muscles of the larynx are divided into two functional groups: extrinsic (move the entire larynx) and intrinsic (move laryngeal cartilages relative to each other).

A. Extrinsic Laryngeal Muscles

These muscles connect the larynx to surrounding structures (e.g., hyoid bone, sternum, skull base) and move the larynx as a whole during swallowing and phonation.

- Suprahyoid (Laryngeal Elevators): Raise the hyoid bone and thus the larynx.

- Digastric, Stylohyoid, Mylohyoid, Geniohyoid: These are primarily hyoid elevators.

- Also, the pharyngeal elevators: Stylopharyngeus, Salpingopharyngeus, Palatopharyngeus can indirectly elevate the larynx.

- Infrahyoid (Laryngeal Depressors): Lower the hyoid bone and larynx.

- Sternohyoid, Omohyoid, Sternothyroid. (Note: Thyrohyoid elevates the larynx by raising the thyroid cartilage relative to the hyoid, but depresses the hyoid).

B. Intrinsic Laryngeal Muscles

These muscles act on the laryngeal cartilages themselves, controlling the tension and position of the vocal folds, thereby modulating phonation and protecting the airway. They are mostly supplied by the recurrent laryngeal nerve, with one exception.

- Muscles Affecting Vocal Fold Length & Tension:

- Cricothyroid (Primary Tensor): Tenses and elongates the vocal folds. Innervated by the external laryngeal nerve (branch of superior laryngeal nerve).

- Thyroarytenoid (Relaxer/Shortener): Shortens and relaxes the vocal folds. It forms the main mass of the vocal folds themselves.

- Muscles Affecting Rima Glottidis (Space between Vocal Folds):

- Posterior Cricoarytenoid (Only Abductor): Abducts (opens) the vocal folds, widening the rima glottidis. This is the most important muscle for maintaining a patent airway, especially during inspiration.

- Lateral Cricoarytenoid (Adductor): Adducts (closes) the vocal folds, narrowing the rima glottidis.

- Transverse Arytenoid (Adductor): Adducts the vocal folds by bringing the arytenoid cartilages together, closing the posterior part of the rima glottidis. This is the only intrinsic laryngeal muscle that is single (not paired).

- Oblique Arytenoids (Adductor & Sphincter): Work with the transverse arytenoid to adduct the vocal folds. Also act as sphincters of the laryngeal inlet by approximating the aryepiglottic folds.

Functional Summary:

- Airway Opening (Inspiration): Posterior cricoarytenoids (abduct vocal folds).

- Airway Closing (Protection/Phonation): Lateral cricoarytenoids, transverse arytenoid, oblique arytenoids (adduct vocal folds).

- Vocal Fold Tension/Pitch: Cricothyroid (tenses/raises pitch), Thyroarytenoid (relaxes/lowers pitch).

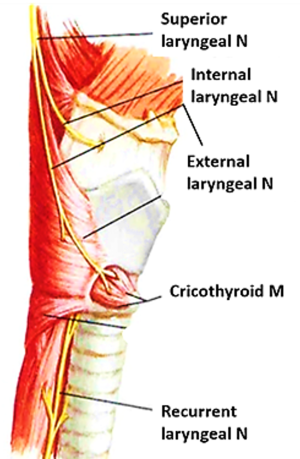

Nerve Supply of the Larynx

The larynx receives its innervation from branches of the Vagus Nerve (CN X): the Superior Laryngeal Nerve and the Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve.

A. Superior Laryngeal Nerve (Branch of Vagus Nerve)

Divides into two terminal branches:

Internal Laryngeal Nerve:

- Sensory: Provides sensory innervation to the laryngeal mucosa above the vocal folds. This includes the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, and the superior part of the laryngeal vestibule. It is responsible for the afferent limb of the laryngeal adductor reflex (cough reflex).

- Autonomic: Contains secretomotor fibers to laryngeal glands.

- Course: Pierces the thyrohyoid membrane.

External Laryngeal Nerve:

- Motor: Provides motor innervation to the cricothyroid muscle (the only intrinsic laryngeal muscle not supplied by the recurrent laryngeal nerve).

- Clinical Significance: Damage to this nerve causes hoarseness due to loss of tension in the vocal folds.

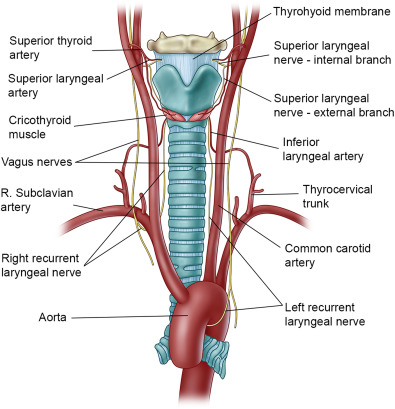

B. Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve (Branch of Vagus Nerve)

- Motor: Provides motor innervation to all intrinsic laryngeal muscles except the cricothyroid. This includes the posterior cricoarytenoid, lateral cricoarytenoid, transverse arytenoid, oblique arytenoids, and thyroarytenoid muscles.

- Sensory: Provides sensory innervation to the laryngeal mucosa below the vocal folds.

- Course:

- The right recurrent laryngeal nerve loops around the right subclavian artery.

- The left recurrent laryngeal nerve loops around the arch of the aorta.

- Both ascend in the tracheoesophageal groove to reach the larynx.

- Clinical Significance:

- Highly vulnerable to injury during neck and thoracic surgeries (e.g., thyroidectomy, cardiac surgery, esophageal surgery) due to its long course.

- Unilateral damage: Causes hoarseness or dysphonia due to paralysis of the ipsilateral vocal fold (typically paramedian position).

- Bilateral damage: Can be life-threatening, as both vocal folds become paralyzed in the adducted position, leading to severe airway obstruction and inspiratory stridor.

Blood Supply of the Larynx

The larynx has a rich blood supply derived from the superior and inferior thyroid arteries.

A. Arterial Supply

- Superior Laryngeal Artery:

- Origin: Branch of the superior thyroid artery (which comes from the external carotid artery).

- Distribution: Supplies the larynx above the vocal folds.

- Course: Accompanies the internal laryngeal nerve, piercing the thyrohyoid membrane.

- Inferior Laryngeal Artery:

- Origin: Branch of the inferior thyroid artery (which comes from the thyrocervical trunk of the subclavian artery).

- Distribution: Supplies the larynx below the vocal folds.

- Course: Accompanies the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

B. Venous Drainage

- Superior Laryngeal Vein:

- Drainage: Drains the larynx above the vocal folds.

- Termination: Drains into the superior thyroid vein, which in turn drains into the internal jugular vein.

- Inferior Laryngeal Vein:

- Drainage: Drains the larynx below the vocal folds.

- Termination: Drains into the inferior thyroid vein, which typically drains into the brachiocephalic vein.

Lymph Drainage of the Larynx

Lymphatic drainage of the larynx generally follows its arterial supply and is divided by the vocal folds.

- Above the Vocal Folds (Supraglottic Region):

- Lymphatics follow the superior laryngeal artery.

- Drain into the superior deep cervical lymph nodes (often via prelaryngeal nodes).

- Below the Vocal Folds (Infraglottic Region):

- Lymphatics follow the inferior laryngeal artery.

- Drain into the inferior deep cervical lymph nodes (often via pretracheal and paratracheal nodes).

- Vocal Folds (Glottic Region): This area has a sparse lymphatic supply, which limits the spread of early glottic cancers.

Clinical Correlates (Larynx)

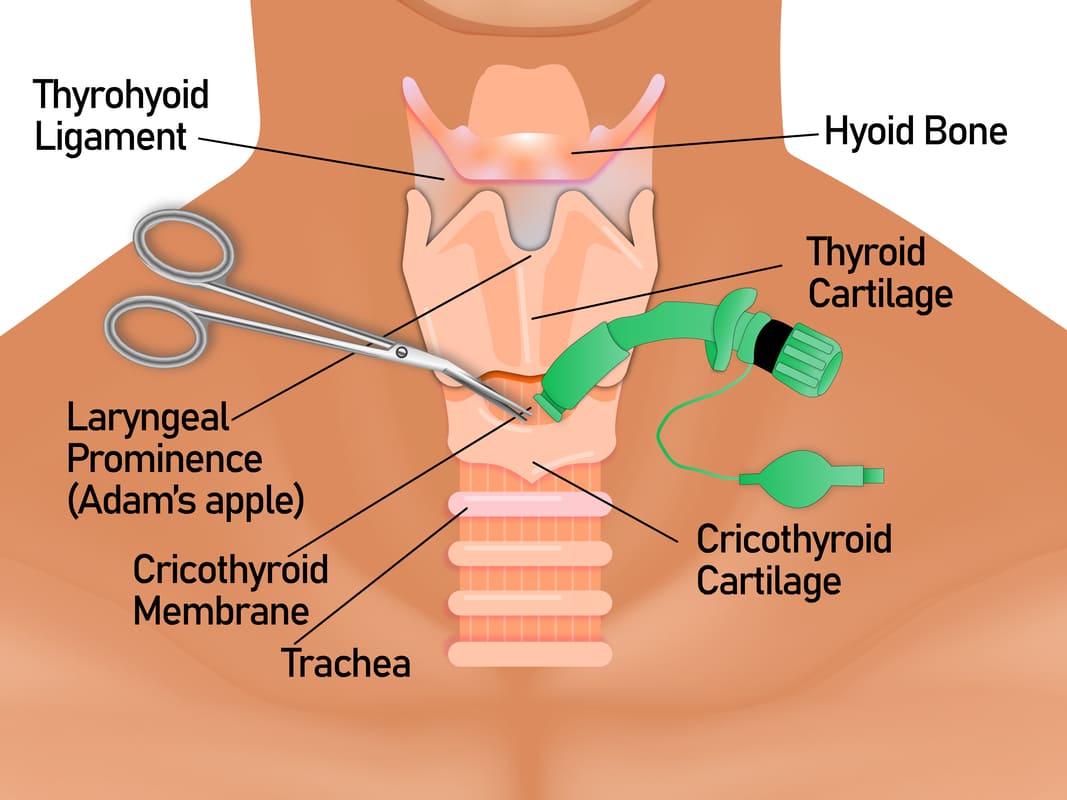

A. Compromised Airway & Cricothyrotomy

- Emergency Airway: When the upper airway is acutely obstructed (e.g., severe anaphylaxis, trauma, foreign body high in the airway) and endotracheal intubation is not possible, an emergency surgical airway is required.

- Cricothyrotomy (Cricothyroidotomy): This procedure involves creating an opening through the cricothyroid membrane to establish an airway. It is often preferred over tracheostomy in emergencies because the membrane is superficial and relatively avascular.

- Procedure Steps (simplified):

- Palpation: Identify the thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilage, and the cricothyroid membrane between them.

- Incision: A small vertical (or horizontal) incision is made through:

- Skin

- Superficial fascia (be mindful of the superficial anterior jugular veins)

- Investing layer of deep cervical fascia

- Cricothyroid membrane

- Tube Insertion: A tube is then inserted through the opening into the trachea.

- Anatomical Layers Incised (as described): Skin, superficial fascia, investing layer of deep cervical fascia, pretracheal fascia, and then the cricothyroid membrane (part of the larynx itself).

- Potential Complications:

- Hemorrhage: While generally less vascular, small branches of the superior thyroid artery often cross the cricothyroid membrane. Care must be taken to avoid these, or a horizontal incision can be used to minimize risk.

- Esophageal Perforation: The esophagus lies directly posterior to the trachea. A deep, uncontrolled incision can potentially pierce the posterior wall of the cricoid cartilage and then the anterior wall of the esophagus. The incision should be carefully controlled to prevent this.

- Subglottic Stenosis: Injury to the cricoid cartilage can lead to subsequent scarring and narrowing of the airway.

- Voice Change: Damage to nearby structures (e.g., recurrent laryngeal nerve, though less likely than with tracheostomy) can affect voice.

B. Other Clinical Correlates of the Larynx

- Laryngitis: Inflammation of the larynx, often leading to hoarseness or loss of voice (aphonia) due to vocal fold swelling.

- Vocal Fold Paralysis:

- Unilateral: Most commonly due to recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, causing hoarseness.

- Bilateral: Can be life-threatening, leading to inspiratory stridor and airway obstruction.

- Laryngeal Cancer: Often associated with smoking and alcohol use. Can affect voice quality (persistent hoarseness is a key symptom).

- Laryngeal Foreign Body: Can cause acute airway obstruction, especially in children.

- Laryngoscopy: Direct visualization of the larynx, often used for diagnosis or intubation.

https://www.doctorsrevisionuganda.com | Whatsapp: 0726113908

Upper Respiratory Tract Quiz

Systems Anantomy

Enter your details to begin the examination.

🛡️ Privacy Note: Results are for tracking and certification purposes only.

Upper Respiratory Tract Quiz

Systems Anantomy

Preparing questions...

Exam Completed!

See your performance breakdown below.