Mutations, Genetic Disorders & Malignancy

Mutations, Genetic Disorders & Malignancy

At the heart of every living organism, from the simplest bacterium to the most complex human, lies the cell. Within each cell, the nucleus houses the genome – a meticulously organized instruction manual written in DNA. This manual dictates everything from cell structure and function to growth, division, and death. When this blueprint is altered, or when the cellular machinery designed to read and execute its instructions malfunctions, the consequences can range from subtle inefficiencies to devastating diseases.

Our focus in this section is to lay down the precise definitions of three fundamental categories of cellular disorders: Mutations, Genetic Disorders, and Malignancy (Cancer). While intimately linked, they represent distinct levels of biological organization and clinical presentation. Understanding their individual definitions and how they relate to one another is crucial for grasping cellular pathology.

Defining Key Terms

A. Mutation

- Definition: A mutation is defined as a heritable change in the nucleotide sequence of the genetic material (DNA or RNA in some viruses). This change can involve a single base pair, a segment of a chromosome, or an entire chromosome. Mutations are the ultimate source of all genetic variation and serve as the raw material for evolution. However, they are also the primary cause of many diseases.

- Key Characteristics:

- Fundamental Unit of Change: A mutation is the most granular level of alteration in the genetic code. It's a change to the DNA itself.

- Heritable: The change must be capable of being passed on to daughter cells during cell division (mitosis) or to offspring (meiosis, if in germ cells).

- Random Occurrence: Mutations are generally random events, not occurring in anticipation of beneficial or harmful effects.

- Variability in Impact: The consequences of a mutation can be:

- Neutral (Silent): No change in protein function or phenotype.

- Beneficial: Rare, providing an evolutionary advantage.

- Harmful (Pathogenic): Leading to disease or impaired function.

- Context: Mutations can occur in any cell of the body.

- Germline Mutations: Occur in germ cells (sperm or egg) and are heritable, meaning they can be passed down to offspring.

- Somatic Mutations: Occur in somatic cells (body cells) after conception. They are not heritable but can contribute to diseases in the affected individual, most notably cancer.

B. Genetic Disorder

- Definition: A genetic disorder is a disease caused, in whole or in part, by a change in an individual's DNA sequence. These disorders arise directly from specific mutations or abnormalities in the genome. The presence of these genetic alterations leads to an abnormal or absent gene product (protein), which in turn disrupts normal cellular function and manifests as a disease.

- Key Characteristics:

- Etiology: The primary cause is a genetic abnormality.

- Inherited or De Novo: Genetic disorders can be inherited from parents (germline mutations) or can arise spontaneously (de novo mutations) in the egg, sperm, or early embryonic development.

- Range of Presentation: They can present at any stage of life, from prenatal development to old age, and vary widely in severity and penetrance (the proportion of individuals with the mutation who express the phenotype).

- Predictable Inheritance Patterns: For many genetic disorders, their inheritance follows Mendelian patterns (e.g., autosomal dominant, recessive, X-linked), allowing for genetic counseling and risk assessment.

- Relationship to Mutation: A genetic disorder is the clinical manifestation of one or more underlying mutations. Without a mutation (or a chromosomal abnormality, which itself is a large-scale mutation), a genetic disorder cannot exist. The mutation is the cause; the genetic disorder is the effect/disease.

C. Malignancy (Cancer)

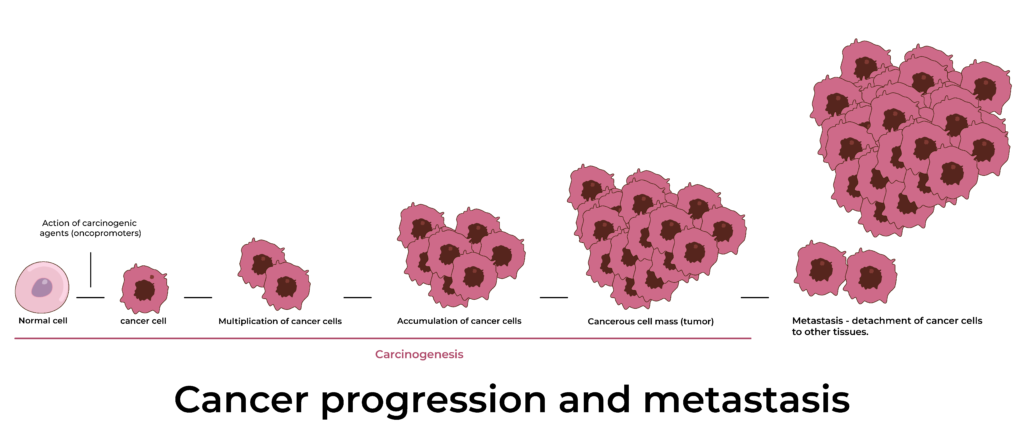

- Definition: Malignancy, commonly known as cancer, is a broad group of diseases characterized by the uncontrolled growth and division of abnormal cells, with the ability to invade adjacent tissues (invasion) and spread to distant sites in the body (metastasis). These abnormal cells form masses called tumors (neoplasms), which can be benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). Malignancy specifically refers to the latter.

- Key Characteristics:

- Uncontrolled Proliferation: Cancer cells ignore normal growth-regulating signals, leading to continuous and excessive cell division.

- Loss of Differentiation: Cancer cells often lose their specialized features and functions, becoming more primitive or anaplastic.

- Invasion: Malignant cells can breach normal tissue boundaries and infiltrate surrounding healthy tissues.

- Metastasis: The hallmark of malignancy, where cancer cells detach from the primary tumor, travel through the bloodstream or lymphatic system, and establish secondary tumors in distant organs.

- Genomic Instability: Cancer cells typically accumulate numerous genetic alterations (mutations) over time, contributing to their abnormal behavior.

- Relationship to Mutation: Cancer is fundamentally a disease of accumulated somatic mutations. It arises when a series of specific mutations occur in critical genes that control cell growth, division, differentiation, and DNA repair. While some cancers have an inherited genetic predisposition (due to germline mutations in cancer-susceptibility genes), the vast majority of cancers develop from a series of acquired somatic mutations throughout an individual's lifetime. These mutations allow cells to bypass normal regulatory mechanisms and acquire the "hallmarks of cancer."

Differentiating and Recognizing Interconnectedness

While all three terms are linked by changes in DNA, their scope and implications differ significantly:

- Mutation (The Event/Change): This is the fundamental alteration in the DNA sequence. It's the cause. Think of it as a typo in the instruction manual.

- Example: A single base pair change from A to T in a specific gene.

- Genetic Disorder (The Inherited Disease): This is a disease condition that results directly from one or more specific mutations (germline or de novo) that are present in all cells of the affected individual (or at least in the germline if inherited). It's the disease state stemming from a genetic blueprint flaw.

- Example: Sickle Cell Anemia is a genetic disorder caused by a single point mutation in the beta-globin gene, leading to abnormal hemoglobin. This mutation is present in almost all cells of affected individuals from conception.

- Malignancy (The Acquired Disease of Uncontrolled Growth): This is a complex disease driven by the accumulation of multiple somatic mutations (and sometimes initial germline mutations) in a subset of cells within a tissue, leading to uncontrolled proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. It's the culmination of multiple "typos" that enable a cell to become rogue.

- Example: Colon cancer develops from epithelial cells that acquire a series of mutations (e.g., in APC, KRAS, TP53 genes) over years, allowing them to transform into malignant cells. These mutations are typically present only in the cancerous cells, not in the patient's other healthy cells (unless there was an inherited predisposition).

| Feature | Mutation | Genetic Disorder | Malignancy (Cancer) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nature | Change in DNA sequence | Disease caused by specific genetic alterations | Disease of uncontrolled cell growth, invasion, and metastasis |

| Scope | Molecular (DNA level) | Organismal (disease phenotype) | Organismal (disease phenotype) from specific rogue cells |

| Primary Cause | Error in DNA replication/repair, mutagens | Underlying genetic alteration (germline/de novo) | Accumulation of somatic mutations in critical regulatory genes (often with germline predisposition) |

| Inheritability | Can be germline (heritable) or somatic (not heritable) | Often inherited (Mendelian), or de novo | Somatic (not inherited by offspring), but predisposition can be inherited |

| Cellular Impact | Altered gene product/function | Dysfunctional cellular processes, disease | Loss of growth control, differentiation, invasiveness, metastasis |

I. The Nature of Genetic Disorders Revisited

As defined in Objective 1, a genetic disorder is a condition caused by abnormalities in an individual's DNA. These abnormalities can range from a single base pair change (a point mutation) to a large-scale chromosomal defect. The key characteristic is that the genetic alteration directly leads to the disease phenotype.

These disorders manifest due to:

- Abnormal Gene Products: A mutation might lead to a non-functional protein, a partially functional protein, or an abnormally structured protein.

- Absent Gene Products: A mutation might prevent a gene from being transcribed or translated, leading to the complete absence of a crucial protein.

- Over-expression of Gene Products: In some rare cases, a mutation might lead to an overproduction of a gene product, causing cellular imbalance.

Understanding the type of genetic alteration is crucial for diagnosis, prognosis, genetic counseling, and potential therapeutic strategies.

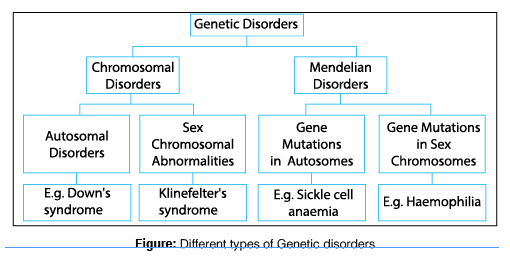

II. Classification of Genetic Disorders

Genetic disorders are broadly categorized into three main types based on the scale and nature of the genetic alteration:

A. Single-Gene (Mendelian) Disorders

These disorders are caused by a mutation in a single gene. Because they follow predictable patterns of inheritance (originally described by Gregor Mendel), they are often referred to as Mendelian disorders. They are typically categorized based on whether the affected gene is on an autosome (non-sex chromosome) or a sex chromosome (X or Y), and whether one or two copies of the mutated gene are required for the disease to manifest (dominant vs. recessive).

1. Autosomal Dominant

Description: A disorder that occurs when only one copy of an altered gene on a non-sex chromosome (autosome) is sufficient to cause the disorder. The affected individual typically has an affected parent, and each child of an affected parent has a 50% chance of inheriting the disorder. The trait appears in every generation.

Key Characteristics:

- Males and females are affected equally.

- Affected individuals usually have an affected parent.

- Can occur de novo (new mutation) in individuals with no family history.

- Affected individuals have a 50% chance of passing the condition to each child.

Examples:

- Huntington's Disease: A neurodegenerative disorder characterized by involuntary movements, cognitive decline, and psychiatric problems. Caused by a mutation in the

HTTgene. - Marfan Syndrome: A connective tissue disorder affecting the skeleton, eyes, heart, and blood vessels. Caused by a mutation in the

FBN1gene. - Achondroplasia: A form of dwarfism resulting from a mutation in the

FGFR3gene, affecting bone growth.

2. Autosomal Recessive

Description: A disorder that occurs when two copies of an altered gene (one from each parent) on a non-sex chromosome are required for the disorder to manifest. Individuals with only one copy of the altered gene are "carriers" – they typically do not show symptoms but can pass the gene to their offspring.

Key Characteristics:

- Males and females are affected equally.

- Affected individuals often have unaffected parents who are carriers.

- Parents who are both carriers have a 25% chance with each pregnancy of having an affected child, a 50% chance of having a carrier child, and a 25% chance of having an unaffected, non-carrier child.

- The trait often "skips" generations in family pedigrees.

Examples:

- Cystic Fibrosis: A severe disorder affecting mucus and sweat glands, primarily impacting the lungs and digestive system. Caused by mutations in the

CFTRgene. - Sickle Cell Anemia: A blood disorder characterized by abnormally shaped red blood cells, leading to anemia, pain crises, and organ damage. Caused by a point mutation in the

HBBgene. - Tay-Sachs Disease: A neurodegenerative disorder prevalent in certain populations, leading to progressive destruction of nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. Caused by mutations in the

HEXAgene.

3. X-Linked Dominant

Description: A disorder caused by a mutation on the X chromosome where only one copy of the altered gene is sufficient to cause the disorder.

Key Characteristics:

- Affected males are usually more severely affected than affected females (who have a second, normal X chromosome).

- Affected fathers transmit the trait to all their daughters but none of their sons.

- Affected mothers have a 50% chance of transmitting the trait to each child (son or daughter).

- Rarely seen due to severity in males often leading to early lethality.

Examples:

- Rett Syndrome: A neurodevelopmental disorder almost exclusively affecting females. Caused by a mutation in the

MECP2gene. Males with the mutation usually do not survive to term or die shortly after birth. - Fragile X Syndrome: (sometimes considered X-linked dominant with variable penetrance): While often discussed as a cause of intellectual disability, it is also on the spectrum, particularly due to the presence of

FMR1gene mutations.

4. X-Linked Recessive

Description: A disorder caused by a mutation on the X chromosome where two copies of the altered gene are required in females for the disorder to manifest, but only one copy is required in males (who only have one X chromosome).

Key Characteristics:

- Males are predominantly affected.

- Affected males cannot pass the trait to their sons, but all their daughters will be carriers.

- Carrier mothers have a 50% chance of having an affected son and a 50% chance of having a carrier daughter with each pregnancy.

- Affected females are rare, usually occurring if an affected father and a carrier mother have a daughter together.

Examples:

- Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD): A severe, progressive muscle-wasting disease primarily affecting males. Caused by mutations in the

DMDgene. - Hemophilia A and B: Blood clotting disorders characterized by prolonged bleeding. Hemophilia A is caused by mutations in the

F8gene; Hemophilia B by mutations in theF9gene. - Red-Green Color Blindness: A common condition where individuals have difficulty distinguishing between shades of red and green.

5. Mitochondrial Inheritance

Description: Disorders caused by mutations in the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), rather than nuclear DNA. Mitochondria are organelles within cells responsible for energy production, and they contain their own small circular DNA.

Key Characteristics:

- Passed down exclusively from the mother to all her children (both sons and daughters).

- Fathers do not pass on mitochondrial disorders to their children.

- Can affect a wide range of organs, particularly those with high energy demands (brain, muscles, heart).

- Variable expressivity due to heteroplasmy (mixture of mutated and normal mtDNA).

Examples:

- Leber's Hereditary Optic Neuropathy (LHON): A condition leading to progressive vision loss, typically in young adulthood.

- MELAS Syndrome (Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Stroke-like Episodes): A severe multisystem disorder affecting the brain, muscles, and other organs.

B. Chromosomal Disorders

These disorders result from changes in the number or structure of chromosomes, rather than mutations in single genes. These changes are often large enough to be visible under a microscope when karyotyping is performed.

1. Aneuploidies

Description: An abnormal number of chromosomes. This usually means having an extra chromosome (trisomy) or missing a chromosome (monosomy). It typically arises from non-disjunction during meiosis (when chromosomes fail to separate properly during egg or sperm formation).

Examples:

- Trisomy 21 (Down Syndrome): The most common human aneuploidy, characterized by an extra copy of chromosome 21 (47, XX or XY, +21). Leads to intellectual disability, distinctive facial features, and often heart defects.

- Trisomy 18 (Edwards Syndrome): An extra copy of chromosome 18. Severe intellectual disability and multiple congenital anomalies; most affected infants do not survive beyond the first year.

- Trisomy 13 (Patau Syndrome): An extra copy of chromosome 13. Very severe developmental anomalies; very poor prognosis.

- Monosomy X (Turner Syndrome): Females with only one X chromosome (45, X). Characterized by short stature, ovarian dysfunction, and specific physical features.

- XXY (Klinefelter Syndrome): Males with an extra X chromosome (47, XXY). Leads to infertility, reduced secondary male characteristics, and often learning difficulties.

2. Structural Rearrangements

Description: Changes in the structure of one or more chromosomes, where genetic material is either lost, gained, or rearranged. These can be balanced (no net loss or gain of genetic material) or unbalanced (net loss or gain).

Types:

- Deletions: A portion of a chromosome is missing or deleted.

- Example: Cri-du-chat Syndrome: Caused by a deletion on the short arm of chromosome 5, leading to intellectual disability, microcephaly, and a characteristic cat-like cry in infancy.

- Duplications: A portion of a chromosome is duplicated, resulting in extra genetic material.

- Example: Some forms of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease are caused by duplication of the

PMP22gene on chromosome 17.

- Example: Some forms of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease are caused by duplication of the

- Translocations: A segment of one chromosome breaks off and attaches to another chromosome.

- Reciprocal Translocation: Segments from two different chromosomes are exchanged. If balanced, the individual is usually healthy but can have reproductive issues. If unbalanced in offspring, it can lead to significant problems (e.g., specific forms of Down Syndrome).

- Robertsonian Translocation: Involves two acrocentric chromosomes that fuse at the centromere, with loss of the short arms. Can lead to unbalanced offspring (e.g., a form of Down Syndrome where an extra chromosome 21 is attached to another chromosome, usually chromosome 14).

- Inversions: A segment of a chromosome breaks off, flips upside down, and reattaches. If the genes are still functional and present in the correct dosage, the individual may be healthy but can have reproductive issues.

C. Multifactorial (Complex) Disorders

These disorders result from a complex interaction of multiple genes (polygenic inheritance) and environmental factors. They do not follow simple Mendelian inheritance patterns, making them more challenging to predict and study. Many common chronic diseases fall into this category.

Key Characteristics:

- Polygenic: Involve multiple genes, each contributing a small effect.

- Environmental Influence: Non-genetic factors (lifestyle, diet, exposure to toxins, infections, etc.) play a significant role.

- Familial Clustering: Tend to run in families, but without clear Mendelian patterns.

- Threshold Effect: A certain number of "risk genes" and environmental triggers must accumulate before the disease manifests.

Examples:

- Heart Disease: Includes coronary artery disease, hypertension, and stroke. Influenced by genes related to lipid metabolism, blood pressure regulation, and inflammation, combined with diet, exercise, smoking, etc.

- Diabetes (Type 2): Involves genes affecting insulin production, insulin sensitivity, and glucose metabolism, alongside lifestyle factors like obesity and physical activity.

- Asthma: Genetic predispositions to allergic responses and airway inflammation, combined with environmental triggers like allergens, pollutants, and respiratory infections.

- Obesity: Influenced by numerous genes regulating appetite, metabolism, and fat storage, interacting with dietary habits and physical activity levels.

- Alzheimer's Disease: While some forms are monogenic (early-onset), the more common late-onset form is multifactorial, with genes like

APOE(specifically APOE-e4 allele) being a significant risk factor, alongside environmental and lifestyle factors. - Cleft Lip and Palate: A birth defect affected by several genes involved in facial development and environmental factors.

I. Mutation

A mutation is a permanent, heritable change in the nucleotide sequence of the genetic material (DNA or, in some viruses, RNA). It represents an alteration from the wild-type (normal) sequence. Mutations are the primary source of genetic variation within populations and are the ultimate driving force of evolution. However, when these changes occur in critical regions of the genome or lead to non-functional gene products, they are often deleterious, causing cellular dysfunction and disease.

Significance as a Change in DNA Sequence: DNA serves as the cell's master blueprint, containing the instructions for building and operating all cellular components, especially proteins. Proteins perform most of the cell's functions and are essential for the structure, function, and regulation of the body's tissues and organs. A change in the DNA sequence directly impacts the genetic code, which, through transcription and translation, dictates the sequence of amino acids in a protein. Even a single nucleotide change can drastically alter a protein's structure, stability, or function, or even prevent its production altogether. This alteration at the molecular level is the root cause of many genetic disorders and plays a central role in the development of cancer.

II. Classification of Mutation Types

Mutations can be broadly classified based on the scale of the change in the genetic material.

A. Gene Mutations (Small-Scale Mutations)

These involve changes in the nucleotide sequence within a single gene.

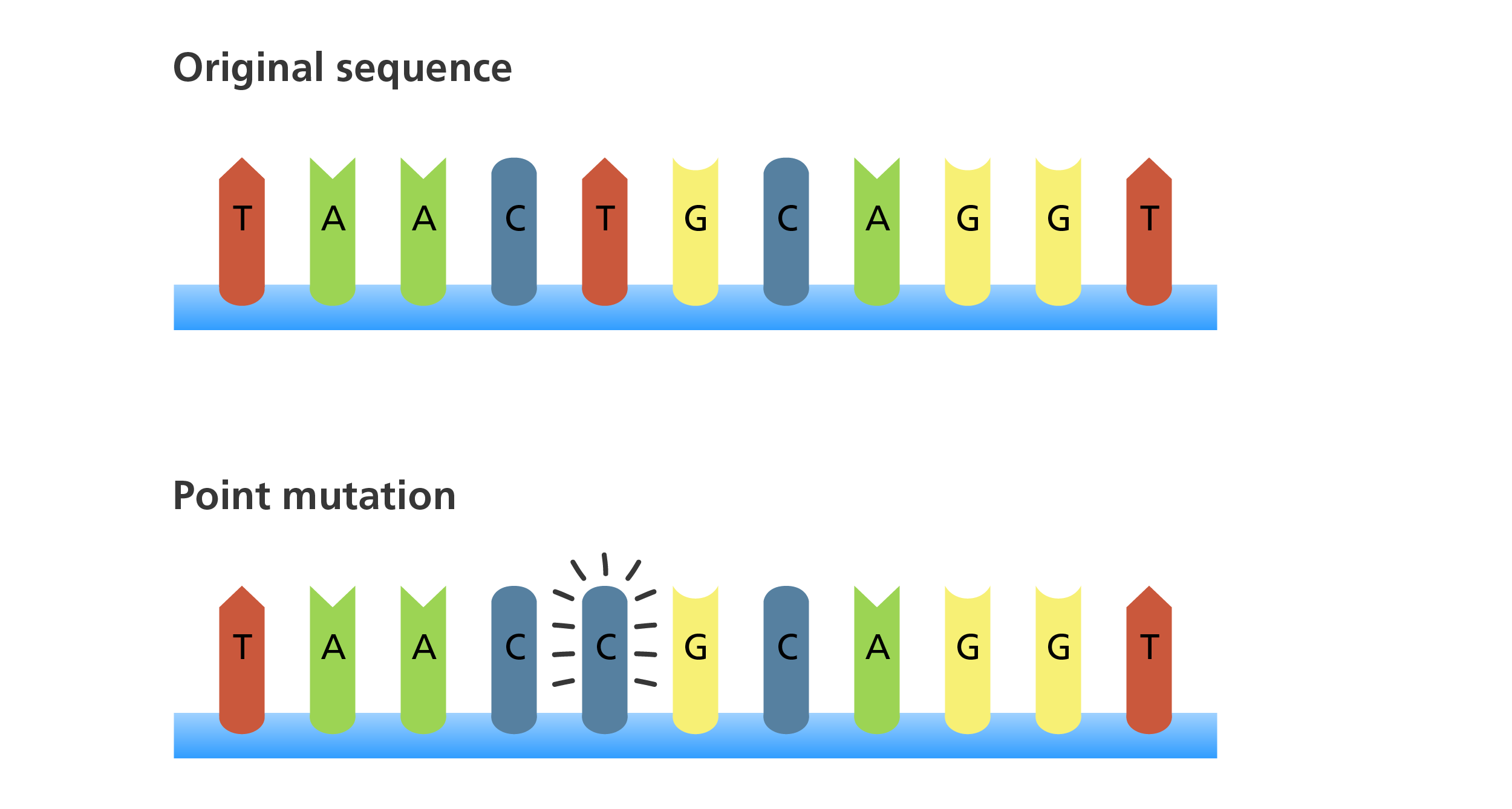

- Point Mutations: A point mutation is a change in a single nucleotide base pair. These are the most common type of gene mutation.

- a. Substitution: One nucleotide is replaced by another.

- Missense Mutation: A base pair substitution that results in a codon that codes for a different amino acid. The protein is still produced but has a changed amino acid sequence, which can range from benign to severely debilitating.

- Example: Sickle Cell Anemia. A single nucleotide substitution (A to T) in the beta-globin gene changes a codon from GAG (coding for Glutamic Acid) to GTG (coding for Valine). This single amino acid change dramatically alters the structure and function of hemoglobin.

- Nonsense Mutation: A base pair substitution that changes a codon for an amino acid into a stop codon (UAA, UAG, UGA in mRNA). This prematurely terminates protein synthesis, leading to a truncated (shortened) and usually non-functional protein.

- Example: Many severe genetic disorders like some forms of Duchenne muscular dystrophy or cystic fibrosis can be caused by nonsense mutations.

- Silent Mutation: A base pair substitution that changes a single nucleotide, but does not change the amino acid sequence of the protein. This occurs because of the degeneracy of the genetic code.

- Example: A change from GGU to GGC still codes for Glycine.

- Missense Mutation: A base pair substitution that results in a codon that codes for a different amino acid. The protein is still produced but has a changed amino acid sequence, which can range from benign to severely debilitating.

- a. Substitution: One nucleotide is replaced by another.

- Frameshift Mutations: These mutations occur when nucleotides are added (insertion) or removed (deletion) from the DNA sequence in numbers that are not multiples of three. Since the genetic code is read in triplets (codons), an insertion or deletion of one or two nucleotides shifts the "reading frame" of the mRNA sequence downstream from the mutation. This typically leads to a completely different sequence of amino acids, often creating a premature stop codon, resulting in a severely altered or truncated, non-functional protein.

- a. Insertion: The addition of one or more nucleotide base pairs into a DNA sequence.

- b. Deletion: The removal of one or more nucleotide base pairs from a DNA sequence.

- Example (Insertion): If the original sequence is

THE BIG RED FOX, andBLUis inserted afterBIG, it becomesTHE BIG BLU RED FOX. The meaning of subsequent words is lost. In DNA, inserting one base will shift all subsequent codons. - Example (Deletion): If the original sequence is

THE BIG RED FOX, andREDis deleted, it becomesTHE BIG FOX. If onlyRis deleted, it becomesTHE BIG EDF OX. - Clinical Impact: Frameshift mutations are often highly detrimental, as they usually result in non-functional proteins. Many severe genetic diseases, like Tay-Sachs disease and some types of beta-thalassemia, are caused by frameshift mutations.

B. Chromosomal Mutations (Large-Scale Mutations)

These involve large-scale changes to the structure or number of chromosomes, detectable by karyotyping. It's important to reiterate that they are a type of mutation, just at a larger scale than gene mutations.

- Changes in Chromosome Number (Aneuploidy):

- Trisomy (e.g., Down Syndrome - extra chromosome 21)

- Monosomy (e.g., Turner Syndrome - missing X chromosome)

- Changes in Chromosome Structure:

- Deletions (e.g., Cri-du-chat Syndrome - deletion on chromosome 5)

- Duplications

- Translocations

- Inversions

III. Causes of Mutations

Mutations can arise through two main mechanisms:

A. Spontaneous Mutations

These occur naturally as a result of errors in normal cellular processes, primarily during DNA replication and repair.

- Errors in DNA Replication: DNA polymerase, the enzyme responsible for copying DNA, is highly accurate, but not perfect. Occasionally, it inserts an incorrect nucleotide, leading to a point mutation. These errors are usually corrected by DNA repair mechanisms, but some escape detection.

- Tautomeric Shifts: Nucleotides can exist in different tautomeric forms. If a base undergoes a tautomeric shift right before or during replication, it can temporarily change its base-pairing properties, leading to a misincorporation of a nucleotide.

- Slippage during Replication: Especially in regions with repetitive sequences, DNA polymerase can "slip," leading to the insertion or deletion of short stretches of nucleotides, causing frameshift mutations.

- Spontaneous Chemical Changes:

- Depurination: The loss of a purine base (Adenine or Guanine) from the DNA backbone. If unrepaired, replication across such a site can lead to nucleotide incorporation errors.

- Deamination: The spontaneous removal of an amino group from a base (e.g., Cytosine deaminating to Uracil). Uracil pairs with Adenine, leading to a C-G to T-A transition if unrepaired.

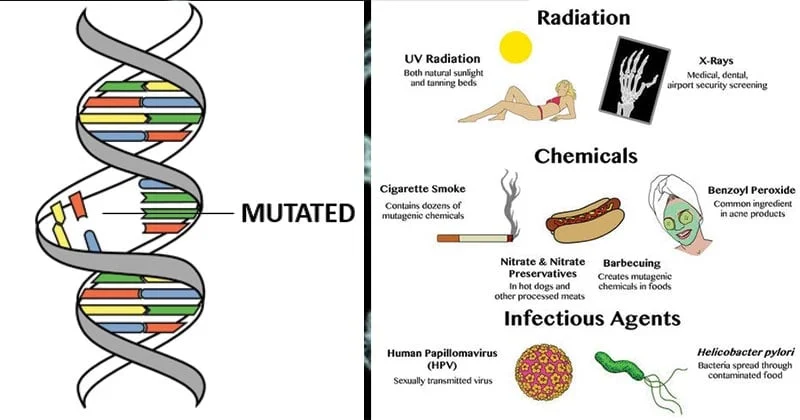

B. Induced Mutations

These are mutations caused by external agents called mutagens.

- Chemical Mutagens:

- Base Analogs: Chemicals structurally similar to normal DNA bases that can be incorporated into DNA during replication, leading to mispairing (e.g., 5-bromouracil, a thymine analog, can pair with guanine).

- Alkylating Agents: Add alkyl groups to DNA bases, altering their pairing properties or causing them to be removed (e.g., mustard gas).

- Intercalating Agents: Flat, planar molecules that insert themselves between stacked DNA base pairs, distorting the helix and leading to frameshift mutations during replication (e.g., ethidium bromide, acridine dyes).

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): Byproducts of normal metabolism (or environmental exposure) that can damage DNA bases (e.g., oxidation of guanine to 8-oxo-guanine, which can mispair with adenine).

- Radiation:

- Ionizing Radiation (e.g., X-rays, gamma rays, cosmic rays): High-energy radiation that can cause direct damage to DNA, including single and double-strand breaks, deletions, translocations, and other large chromosomal aberrations. It can also generate free radicals that chemically modify DNA bases.

- Non-ionizing Radiation (e.g., UV light): Lower-energy radiation (like sunlight) that causes specific types of DNA damage, primarily the formation of pyrimidine dimers (covalent bonds between adjacent pyrimidine bases, especially thymine dimers). These dimers distort the DNA helix and interfere with replication and transcription.

- Biological Agents:

- Viruses: Some viruses (e.g., human papillomavirus HPV, hepatitis B virus HBV) can integrate their genetic material into the host cell's DNA, potentially disrupting genes or altering gene expression, leading to mutations or chromosomal instability.

- Transposons (Jumping Genes): DNA sequences that can move from one location in the genome to another. Their insertion into a gene can disrupt its function, causing a mutation.

IV. Consequences of Mutations on Protein Function and Cellular Processes

The impact of a mutation depends heavily on its type, location, and the specific gene it affects.

- Loss-of-Function Mutations:

- The most common outcome. The mutation leads to a reduction or complete abolition of the protein's normal function. This can happen if the protein is truncated (nonsense/frameshift), misfolded (missense in a critical region), or not produced at all.

- Result: The cell or organism lacks a necessary enzyme, structural protein, receptor, or regulatory protein, leading to a disease phenotype.

- Examples: Most recessive genetic disorders (e.g., cystic fibrosis, PKU), where the gene product is essential.

- Gain-of-Function Mutations:

- Less common. The mutation results in a protein with a new, enhanced, or uncontrolled function. This often involves proteins that regulate cell growth or signaling pathways.

- Result: The protein might become hyperactive, act in a new context, or be produced at inappropriate times/levels, leading to altered cellular processes.

- Examples: Many oncogenes in cancer involve gain-of-function mutations, where a proto-oncogene is converted into an oncogene that promotes uncontrolled cell growth (e.g., a mutated receptor that is always "on" even without a ligand).

- Dominant Negative Mutations:

- The mutant protein interferes with the function of the normal protein produced by the non-mutated allele in a heterozygote. This often occurs when the protein functions as a multimer (complex of several protein units).

- Result: The presence of the abnormal subunit "poisons" the entire complex, leading to a loss of function, even though a normal copy of the gene is present.

- Examples: Some forms of osteogenesis imperfecta (brittle bone disease) where abnormal collagen chains interfere with the assembly of normal collagen.

- Conditional Mutations:

- The mutation's effect on protein function is dependent on certain environmental conditions (e.g., temperature).

- Result: The protein may be functional under one condition but non-functional under another.

- Examples: Some mutations in bacteria or viruses that only manifest at specific temperatures. Less common as a primary cause of human disease but can be relevant in research.

- Regulatory Mutations:

- Mutations in non-coding regions that affect gene expression (e.g., in promoters, enhancers, introns leading to altered splicing). These don't change the protein sequence directly but alter how much or when a protein is produced.

- Result: Overproduction, underproduction, or inappropriate timing/location of protein expression, leading to cellular imbalance.

- Examples: Some forms of thalassemia are caused by mutations in regulatory regions affecting hemoglobin gene expression.

Overall Impact leading to Disease Phenotypes: When these changes in protein function (or lack thereof) occur in critical cellular pathways (e.g., cell division, metabolism, DNA repair, signaling, structural integrity), the normal physiology of the cell is disrupted. This cellular dysfunction then cascades upwards to affect tissues, organs, and ultimately the entire organism, leading to the diverse array of disease phenotypes observed in genetic disorders and cancer. The accumulation of these detrimental mutations, especially in somatic cells, is the driving force behind the development of malignancy, as we will explore further in Objective 4.

I. Cancer

As established in Objective 1, cancer (malignancy) is fundamentally a disease driven by genetic changes, specifically the accumulation of somatic mutations. Unlike germline mutations which are inherited and present in every cell from conception, somatic mutations occur in non-germline cells (body cells) after conception. These somatic mutations are acquired throughout an individual's lifetime due to errors in DNA replication, exposure to mutagens (carcinogens), or failures in DNA repair mechanisms.

The development of cancer is typically a multi-step process requiring several distinct mutations in key regulatory genes within a single cell lineage. This means one or two mutations are usually not enough to cause cancer; rather, a critical number and combination of specific mutations must accumulate over time. This explains why cancer is predominantly a disease of aging – the longer an organism lives, the more opportunities its cells have to acquire these necessary mutations.

Once a cell acquires a critical set of mutations, it gains selective advantages that allow it to outcompete normal cells, proliferate uncontrollably, and eventually invade and metastasize.

II. The "Hallmarks of Cancer"

In 2000, Douglas Hanahan and Robert Weinberg published a seminal review outlining a conceptual framework for understanding the biological capabilities acquired by cancer cells during their multistep development. These "Hallmarks of Cancer" were updated in 2011 to include emerging capabilities. They provide a comprehensive overview of the fundamental changes that transform a normal cell into a malignant one.

The 8 core hallmarks (with 2 enabling characteristics):

- Sustaining Proliferative Signaling:

- Cancer cells acquire the ability to grow and divide without external signals (growth factors). They become autonomous, often by overproducing growth factors, overexpressing growth factor receptors, or having activating mutations in downstream signaling components.

- Mechanism: Mutations in proto-oncogenes leading to their activation as oncogenes.

- Evading Growth Suppressors:

- Normal cells have mechanisms to halt growth (e.g., cell cycle checkpoints, tumor suppressor proteins like p53 and Rb). Cancer cells bypass these brakes on cell proliferation.

- Mechanism: Inactivating mutations in tumor suppressor genes.

- Resisting Cell Death (Apoptosis):

- Apoptosis (programmed cell death) is a crucial defense mechanism to eliminate damaged or potentially cancerous cells. Cancer cells often acquire mutations that allow them to resist these death signals, ensuring their survival.

- Mechanism: Mutations affecting genes involved in apoptotic pathways (e.g., p53 inactivation, increased anti-apoptotic proteins like Bcl-2).

- Enabling Replicative Immortality:

- Normal cells have a limited number of divisions due to telomere shortening. Cancer cells overcome this by reactivating telomerase (an enzyme that rebuilds telomeres), allowing them to divide indefinitely.

- Mechanism: Activation of telomerase, leading to maintenance of telomere length.

- Inducing Angiogenesis:

- Tumors require a blood supply to grow beyond a very small size (1-2 mm). Cancer cells stimulate the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) to supply oxygen and nutrients and to remove waste products.

- Mechanism: Upregulation of pro-angiogenic factors (e.g., VEGF) and downregulation of anti-angiogenic factors.

- Activating Invasion and Metastasis:

- The defining characteristic of malignancy. Cancer cells acquire the ability to detach from the primary tumor, invade surrounding tissues, enter the bloodstream or lymphatic system, travel to distant sites, and establish secondary tumors (metastasis).

- Mechanism: Loss of cell adhesion molecules (e.g., E-cadherin), increased motility, and secretion of proteases that degrade the extracellular matrix.

- Deregulating Cellular Energetics:

- Cancer cells often reprogram their metabolism to support rapid growth and division, typically relying on aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) even in the presence of oxygen. This allows for rapid production of biomass for cell division.

- Mechanism: Mutations in metabolic enzymes or signaling pathways that alter metabolic preferences.

- Avoiding Immune Destruction:

- The immune system often recognizes and eliminates nascent cancer cells. However, cancer cells evolve mechanisms to evade immune surveillance and destruction.

- Mechanism: Loss of MHC class I molecules, expression of immune checkpoint ligands (e.g., PD-L1), secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines.

Enabling Characteristics:

- Genome Instability and Mutation: This is the underlying force that generates the genetic alterations required for acquiring the other hallmarks. Cancer cells often have defects in DNA repair mechanisms, leading to an accelerated rate of mutation.

- Tumor-Promoting Inflammation: Chronic inflammation can provide growth factors, pro-angiogenic factors, and other molecules that support tumor growth and progression.

III. Differentiating Benign vs. Malignant Tumors

Understanding the differences between benign and malignant tumors is critical for diagnosis and prognosis. Both are abnormal growths of cells (neoplasms), but their biological behavior is vastly different.

| Feature | Benign Tumor | Malignant Tumor (Cancer) |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate | Slow, progressive | Rapid, erratic |

| Differentiation | Well-differentiated (resembles tissue of origin) | Poorly differentiated (anaplastic) or undifferentiated |

| Mitoses | Few, normal | Numerous, often abnormal |

| Nuclei | Small, uniform, normal nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio | Large, pleomorphic (variably shaped), high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio |

| Growth Pattern | Expansive, often encapsulated | Infiltrative, invasive, destructive of surrounding tissue |

| Local Invasion | None | Frequent, invades surrounding tissues |

| Metastasis | None | Frequent (spreads to distant sites via blood/lymph) |

| Recurrence | Unlikely after removal | Common after removal |

| Prognosis | Generally good | Potentially life-threatening |

Key Differentiating Features:

- Differentiation: Malignant cells often lose their specialized features and revert to a more primitive, undifferentiated state (anaplasia). Benign cells maintain their differentiated state.

- Invasion: The ability to break through the basement membrane and invade adjacent normal tissues is a defining characteristic of malignancy. Benign tumors grow by expansion and are often surrounded by a fibrous capsule.

- Metastasis: The spread of cancer cells from the primary tumor to distant sites is the most sinister aspect of malignancy and is virtually exclusive to cancer.

IV. Role of Proto-Oncogenes, Oncogenes, and Tumor Suppressor Genes

The development of cancer is fundamentally a dance between the activation of growth-promoting genes and the inactivation of growth-inhibiting genes.

A. Proto-Oncogenes

- Definition: Normal cellular genes that regulate cell growth, division, and differentiation. They are often involved in signal transduction pathways (e.g., growth factors, growth factor receptors, intracellular signaling molecules, transcription factors).

- Function: Act as "gas pedals" for cell growth and proliferation. They are essential for normal development and tissue maintenance.

- Examples:

RAS,MYC,EGFR,HER2.

B. Oncogenes

- Definition: Mutated (activated) forms of proto-oncogenes. They promote uncontrolled cell growth and proliferation.

- Mechanism of Activation: A proto-oncogene can be converted into an oncogene by several types of mutations:

- Point Mutations: Lead to a hyperactive protein (e.g.,

RASmutations make the protein constantly active). - Gene Amplification: Increased copy number of the gene, leading to overproduction of the protein (e.g.,

HER2amplification in breast cancer). - Chromosomal Translocations: Moving a proto-oncogene to a new location, often under the control of a stronger promoter, or creating a fusion protein with altered function (e.g.,

BCR-ABLfusion gene in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia, caused by the Philadelphia chromosome translocation). - Viral Insertion: Some viruses can insert their DNA near a proto-oncogene, activating its expression.

- Point Mutations: Lead to a hyperactive protein (e.g.,

- Effect: Oncogenes act in a dominant fashion; a single activated oncogene is usually sufficient to promote uncontrolled growth. They push the cell cycle forward.

C. Tumor Suppressor Genes (TSGs)

- Definition: Genes that regulate the cell cycle, initiate apoptosis, or repair DNA damage, thereby suppressing cell proliferation and tumor formation.

- Function: Act as "brakes" on cell growth and proliferation. They prevent genetically damaged cells from dividing. They are the "guardians of the genome."

- Mechanism: Typically require inactivation of both alleles (copies) for their tumor-suppressive function to be lost (Knudson's "two-hit hypothesis"). This can occur through mutation, deletion, or epigenetic silencing.

- Examples:

- p53 (TP53): The "guardian of the genome." Initiates cell cycle arrest or apoptosis in response to DNA damage. Mutations in p53 are found in over 50% of human cancers.

- Rb (Retinoblastoma gene): Regulates the G1-S phase transition of the cell cycle. When active, it prevents cell division.

- BRCA1/BRCA2: Involved in DNA repair. Inherited mutations in these genes significantly increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer.

- APC (Adenomatous Polyposis Coli): Involved in cell adhesion and signal transduction, often mutated in colorectal cancer.

- Effect: Loss of tumor suppressor gene function allows cells with damaged DNA to continue dividing, accumulating more mutations, and escaping normal growth control. They fail to stop the cell cycle.

Interplay in Cancer Development: Cancer arises when there is a critical imbalance: the "gas pedals" (oncogenes) are stuck in the "on" position, and the "brakes" (tumor suppressor genes) have failed. This allows the cell to acquire the various "Hallmarks of Cancer" through successive mutations, leading to uncontrolled proliferation, invasion, and metastasis.

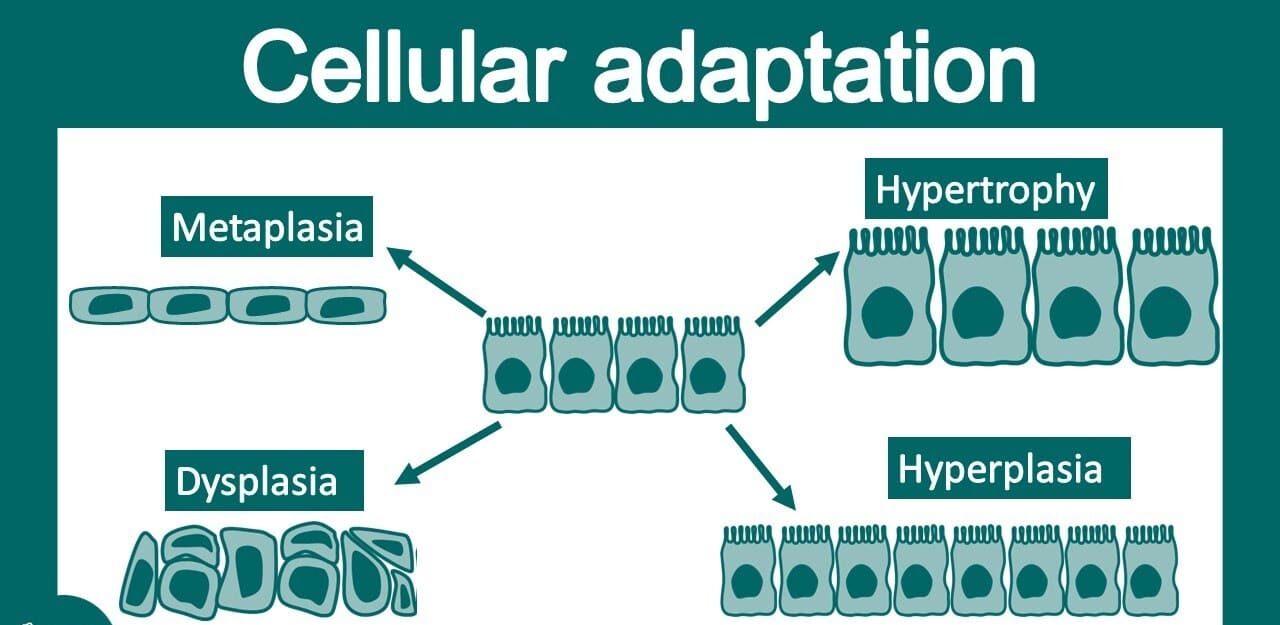

I. Cellular Adaptation

Definition: Cellular adaptation refers to the reversible changes in the size, number, phenotype, metabolic activity, or functions of cells in response to changes in their environment. These adaptations are crucial for cells to maintain homeostasis – the stable equilibrium of internal conditions – when faced with physiological stresses (normal demands) or pathological stimuli (abnormal challenges).

Role in Maintaining Homeostasis: The body's internal environment is constantly fluctuating. Cells must be able to adjust to these fluctuations to survive and function correctly. Cellular adaptations are physiological responses aimed at:

- Minimizing injury: By modifying their structure or function, cells can reduce the impact of stress.

- Achieving a new steady state: Cells reach a new equilibrium where they can survive and carry out their essential functions under the altered conditions.

- Avoiding irreversible damage: Adaptations are a protective mechanism. If the stress is too severe, prolonged, or the cell's adaptive capacity is exceeded, it leads to cell injury and eventually cell death.

Adaptations are generally reversible. If the stress is removed, the cell can often revert to its normal state. However, persistent or overwhelming stress can push cells beyond adaptation into injury and death.

II. Types of Cellular Adaptations

There are four primary types of cellular adaptations:

A. Hypertrophy: Increase in Cell Size

- Description: An increase in the size of individual cells, which in turn leads to an increase in the size of the affected organ or tissue. There is no increase in the number of cells. The enlarged cells synthesize more structural proteins and organelles, enabling them to cope with increased workload.

- Mechanism: Increased workload or demand triggers increased synthesis of proteins (e.g., contractile proteins in muscle, enzymes) and organelles within the cell, leading to its enlargement.

- Causes:

- Physiological (Normal):

- Skeletal muscle hypertrophy: In response to increased workload (e.g., weightlifting) – muscle cells enlarge to generate more force.

- Uterine smooth muscle hypertrophy: During pregnancy, individual smooth muscle cells in the uterus enlarge to accommodate the growing fetus.

- Pathological (Abnormal):

- Cardiac hypertrophy: In response to increased hemodynamic load (e.g., hypertension, aortic stenosis). Heart muscle cells enlarge to pump against increased resistance. This is initially compensatory but can eventually lead to heart failure if the stress is prolonged.

- Physiological (Normal):

- Key Point: Hypertrophy often occurs in tissues composed of cells that have limited capacity for division (e.g., cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle).

B. Hyperplasia: Increase in Cell Number

- Description: An increase in the number of cells in an organ or tissue, leading to an increase in its overall size. This adaptation occurs in tissues where cells are capable of replication (e.g., epithelia, hematopoietic cells, glands).

- Mechanism: Stimulated by growth factors, hormones, or other regulatory signals, leading to increased cell proliferation.

- Causes:

- Physiological (Normal):

- Hormonal hyperplasia: Endometrial hyperplasia during the menstrual cycle under estrogen stimulation. Breast glandular hyperplasia during puberty and pregnancy to prepare for lactation.

- Compensatory hyperplasia: Liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy. Wound healing involving proliferation of fibroblasts and endothelial cells.

- Pathological (Abnormal):

- Endometrial hyperplasia: Due to excessive or prolonged estrogen stimulation (e.g., without progesterone counteraction), leading to abnormal uterine bleeding. This can be a precursor to cancer.

- Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH): Common in aging men, due to hormonal imbalances, leading to an enlarged prostate gland and urinary obstruction.

- Psoriasis: Hyperplasia of epidermal cells due to chronic inflammation.

- Physiological (Normal):

- Key Point: Pathological hyperplasia is abnormal but reversible if the stimulating factor is removed. However, it can be a fertile ground for cancer development if mutations accumulate (e.g., endometrial hyperplasia to adenocarcinoma).

C. Atrophy: Decrease in Cell Size and/or Number

- Description: A reduction in the size of an organ or tissue due to a decrease in the size and/or number of its constituent cells. It represents a state where cells have reduced their structural components to a size that allows for survival.

- Mechanism: Decreased protein synthesis and increased protein degradation (via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and autophagy). Cells dismantle nonessential components to survive.

- Causes:

- Physiological (Normal):

- Thymus atrophy during childhood.

- Post-menopausal ovarian atrophy due to decreased estrogen stimulation.

- Embryonic structures such as the notochord and thyroglossal duct during development.

- Pathological (Abnormal):

- Disuse atrophy: Immobilization of a limb (e.g., in a cast) leads to muscle atrophy.

- Denervation atrophy: Loss of nerve supply to a muscle.

- Ischemic atrophy: Reduced blood supply (e.g., renal artery stenosis leading to kidney atrophy).

- Lack of endocrine stimulation: Testicular atrophy due to decreased gonadotropins.

- Inadequate nutrition: Wasting in prolonged starvation (e.g., muscle wasting, cachexia).

- Pressure atrophy: Prolonged pressure on tissues can impair blood supply and cause atrophy (e.g., bedsores).

- Aging (Senile atrophy): Brain atrophy, bone marrow atrophy, etc., due to reduced workload, blood supply, and hormonal stimulation over time.

- Physiological (Normal):

- Key Point: While cells are smaller, they are not dead. If the cause of atrophy is removed, the cells can often return to their normal size and function (e.g., muscle recovery after cast removal).

D. Metaplasia: Reversible Change in Cell Type

- Description: A reversible change in which one mature differentiated cell type is replaced by another mature differentiated cell type. It is an adaptive substitution of cells that are more sensitive to stress by cell types that are better able to withstand the stressful environment.

- Mechanism: Reprogramming of stem cells or undifferentiated mesenchymal cells in the tissue to differentiate along a new pathway, rather than a change in phenotype of already differentiated cells.

- Causes: Chronic irritation or chronic inflammation.

- Examples:

- Squamous Metaplasia (most common):

- Respiratory tract: In chronic cigarette smokers, the normal ciliated columnar epithelial cells of the trachea and bronchi (which are sensitive to smoke) are replaced by more robust, stratified squamous epithelial cells. While these squamous cells are more resilient, they lose the protective functions of cilia and mucus secretion, predisposing to infections and increasing the risk of cancer.

- Uterine cervix: Normal columnar epithelium replaced by squamous epithelium.

- Vitamin A deficiency: Can induce squamous metaplasia in the respiratory tract, urinary tract, and salivary glands.

- Columnar Metaplasia:

- Barrett Esophagus: In chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), the normal stratified squamous epithelium of the lower esophagus is replaced by specialized intestinal-type columnar epithelium (containing goblet cells), which is more resistant to acid. This is a classic example of metaplasia that significantly increases the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

- Squamous Metaplasia (most common):

- Key Point: While metaplasia is an adaptation, it often comes with a trade-off (loss of function of the original cell type) and can be a precursor to malignant transformation if the chronic stress persists. The new cell type might be better suited to the immediate stress, but it may also have an increased propensity for neoplastic change.

Source: https://doctorsrevisionuganda.com | Whatsapp: 0726113908

Disorders of a Cell

Test your knowledge with these 20 questions.

Disorders of a Cell Quiz

Question 1/20

Quiz Complete!

Here are your results, .

Your Score

18/20

90%