ANATOMICAL MOVEMENTS

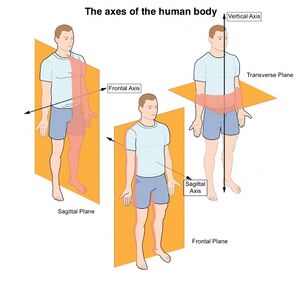

Introduction to Anatomical Planes

Understanding anatomical planes is fundamental to describing the location of structures and, more importantly, the direction of movement within the human body. These are imaginary flat surfaces that pass through the body, dividing it into sections. All movements occur within or parallel to these planes.

A. Standard Anatomical Position Reminder:

Before discussing planes, it's crucial to recall the standard anatomical position:

- Body erect

- Feet slightly apart

- Palms facing forward

- Thumbs pointing away from the body

All descriptions of planes and movements assume the body is in this position.

B. The Three Cardinal Planes:

1. Sagittal Plane

- Definition: A vertical plane that divides the body or an organ into right and left parts.

- Orientation: Runs vertically from front to back.

- Key Divisions:

- Midsagittal (Median) Plane: Lies exactly in the midline, dividing the body into equal right and left halves. Often used as a reference point.

- Parasagittal Planes: All other sagittal planes offset from the midline, dividing the body into unequal right and left parts.

- Movements Associated: Primarily

flexionandextension. These involve anterior-posterior motion. - Analogy: Imagine a wall cutting through your body from your nose to your spine.

2. Frontal (Coronal) Plane

- Definition: A vertical plane that divides the body or an organ into anterior (front) and posterior (back) parts.

- Orientation: Runs vertically from side to side, perpendicular to the sagittal plane.

- Movements Associated: Primarily

abductionandadduction. These involve medial-lateral motion. - Analogy: Imagine a wall cutting through your body from one shoulder to the other.

3. Transverse (Horizontal) Plane

- Definition: A horizontal plane that divides the body or an organ into superior (upper) and inferior (lower) parts.

- Orientation: Runs horizontally, perpendicular to both sagittal and frontal planes.

- Key Divisions: Often referred to as cross-sectional planes, especially in imaging (e.g., CT scans, MRIs).

- Movements Associated: Primarily

rotationalmovements (medial/internal and lateral/external rotation). - Analogy: Imagine a table slicing through your body at the waist.

C. Clinical Relevance of Planes:

- Medical Imaging: Radiologists extensively use these planes to orient images (e.g., MRI, CT, ultrasound) and describe the location of pathologies.

- Surgical Planning: Surgeons plan incisions and approaches based on anatomical planes.

- Rehabilitation: Therapists describe exercises and patient movements in relation to these planes to ensure correct form and target specific muscle groups.

- Biomechanics: Researchers analyze human movement by breaking it down into components occurring in specific planes.

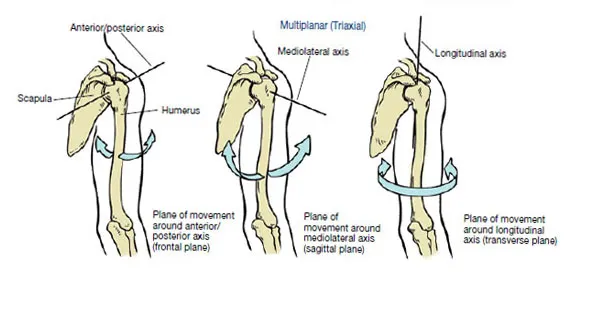

II. Anatomical Axes of Rotation

Movement at a joint occurs around an imaginary line called an axis of rotation. Each axis is perpendicular to the plane in which the movement occurs. Think of the axis as a pivot point around which the bone rotates.

A. The Three Major Axes:

- Mediolateral (Transverse) Axis:

- Orientation: Runs horizontally from side to side (left to right or right to left).

- Relationship to Planes: Perpendicular to the sagittal plane.

- Movements Associated: Movements that occur in the sagittal plane, such as

flexionandextension.- Example: Bending your elbow (flexion) or straightening it (extension) occurs around a mediolateral axis passing through the elbow joint.

- Anteroposterior (Sagittal) Axis:

- Orientation: Runs horizontally from front to back (anterior to posterior or posterior to anterior).

- Relationship to Planes: Perpendicular to the frontal (coronal) plane.

- Movements Associated: Movements that occur in the frontal plane, such as

abductionandadduction.- Example: Lifting your arm out to the side (abduction) or bringing it back to your body (adduction) occurs around an anteroposterior axis passing through the shoulder joint.

- Vertical (Longitudinal) Axis:

- Orientation: Runs vertically from superior to inferior (up and down).

- Relationship to Planes: Perpendicular to the transverse (horizontal) plane.

- Movements Associated: Movements that occur in the transverse plane, primarily

rotationalmovements (medial/internal rotation, lateral/external rotation).- Example: Turning your head left and right (rotation of the neck) occurs around a vertical axis passing through the cervical spine. Rotating your arm inward or outward at the shoulder also occurs around a vertical axis.

B. Summary Table:

| Plane of Movement | Axis of Rotation | Primary Movements |

|---|---|---|

| Sagittal | Mediolateral (Transverse) | Flexion, Extension |

| Frontal (Coronal) | Anteroposterior (Sagittal) | Abduction, Adduction |

| Transverse (Horizontal) | Vertical (Longitudinal) | Rotation (Medial/Lateral) |

C. Importance of Axes:

- Biomechanics: Crucial for analyzing the mechanics of movement and understanding forces acting on joints.

- Exercise Science: Helps in designing exercises that target specific planes of motion and strengthen muscles responsible for movements around particular axes.

- Prosthetics and Orthotics: Design of artificial limbs and braces must consider the natural axes of human joint movement.

- Nodding head "yes" (flexion/extension)

- Shaking head "no" (rotation)

- Jumping jacks (abduction/adduction of arms and legs)

- Bicep curl (flexion/extension of elbow)

- Trunk rotation

III. Classification of Anatomical Movements

Anatomical movements are typically described at synovial joints, which allow for a wide range of motion. Movements are often described in pairs, as they are opposing actions.

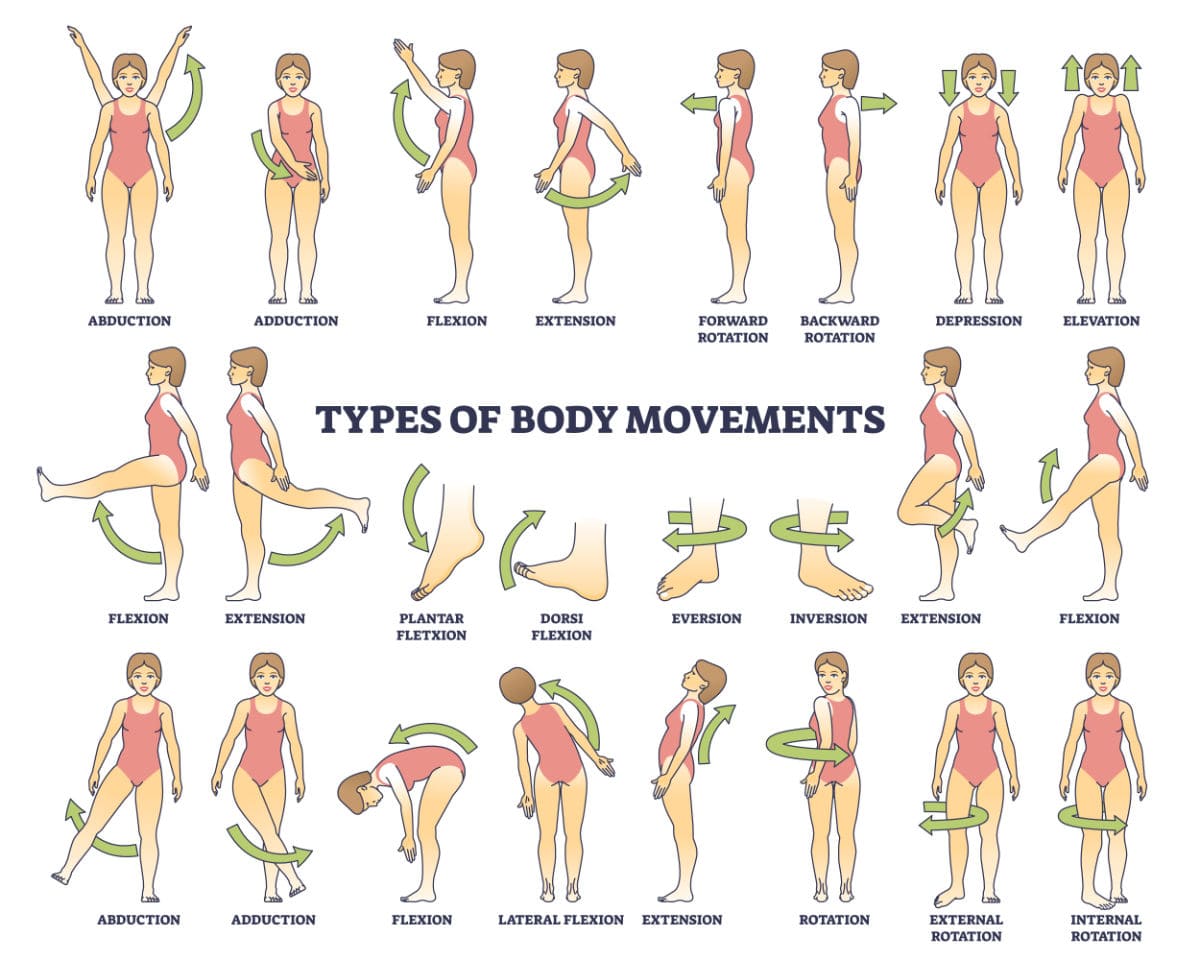

A. Movements in the Sagittal Plane (around a Mediolateral Axis):

1. Flexion:

- Definition: Movement that decreases the angle between two body parts. For most joints, this involves bringing the anterior surfaces closer together, or in the case of the knee and elbow, bringing posterior surfaces closer.

- Examples:

- Shoulder: Bringing the arm forward and upward.

- Elbow: Bending the arm, bringing the forearm closer to the upper arm.

- Wrist: Bending the hand anteriorly towards the forearm.

- Hip: Bringing the thigh forward and upward.

- Knee: Bending the leg, bringing the heel towards the buttocks.

- Trunk/Spine: Bending forward at the waist.

- Neck: Bending the head forward, chin towards the chest.

- Key Muscles (Examples):

Biceps brachii(elbow),Pectoralis major(shoulder),Iliopsoas(hip),Hamstrings(knee).

2. Extension:

- Definition: Movement that increases the angle between two body parts, effectively straightening the joint. It is generally the reverse of flexion.

- Hyperextension: Extension beyond the normal anatomical limit. This can indicate injury or hypermobility.

- Examples:

- Shoulder: Moving the arm backward from the anatomical position.

- Elbow: Straightening the arm.

- Wrist: Straightening the hand with the forearm (or moving it posteriorly).

- Hip: Moving the thigh backward.

- Knee: Straightening the leg.

- Trunk/Spine: Bending backward at the waist.

- Neck: Extending the head backward.

- Key Muscles (Examples):

Triceps brachii(elbow),Latissimus dorsi(shoulder),Gluteus maximus(hip),Quadriceps femoris(knee).

B. Movements in the Frontal (Coronal) Plane (around an Anteroposterior Axis):

1. Abduction:

- Definition: Movement of a limb or body part away from the midline of the body.

- Exceptions: Fingers/toes: away from the midline of the hand/foot.

- Examples:

- Shoulder: Lifting the arm out to the side.

- Hip: Moving the leg out to the side.

- Fingers/Toes: Spreading them apart.

- Key Muscles (Examples):

Deltoid(shoulder),Gluteus medius/minimus(hip).

2. Adduction:

- Definition: Movement of a limb or body part towards the midline of the body.

- Exceptions: Fingers/toes: towards the midline of the hand/foot.

- Examples:

- Shoulder: Bringing the arm back towards the body from an abducted position.

- Hip: Bringing the leg back towards the other leg from an abducted position.

- Fingers/Toes: Bringing them together.

- Key Muscles (Examples):

Pectoralis major,Latissimus dorsi(shoulder),Adductor group(thigh).

C. Movements in the Transverse (Horizontal) Plane (around a Vertical Axis):

1. Medial (Internal) Rotation:

- Definition: Rotational movement of a limb towards the midline of the body (turning the anterior surface inward).

- Examples:

- Shoulder: Turning the arm inward so the palm faces posteriorly (if elbow bent to 90 degrees).

- Hip: Turning the leg inward so the toes point medially.

- Key Muscles (Examples):

Subscapularis,Pectoralis major(shoulder),Gluteus medius/minimus(hip).

2. Lateral (External) Rotation:

- Definition: Rotational movement of a limb away from the midline of the body (turning the anterior surface outward).

- Examples:

- Shoulder: Turning the arm outward so the palm faces anteriorly (if elbow bent to 90 degrees).

- Hip: Turning the leg outward so the toes point laterally.

- Key Muscles (Examples):

Infraspinatus,Teres minor(shoulder),Obturator internus/externus(hip).

D. Combination Movement:

1. Circumduction:

- Definition: A combination of flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction movements, resulting in a conical movement of the distal end of a limb while the proximal end remains relatively stable. It can be seen at ball-and-socket joints.

- Examples:

- Shoulder: Moving the arm in a circle (e.g., pitching a softball).

- Hip: Moving the leg in a circle.

- Wrist: Making circles with your hand.

- Key Muscles: Involves sequential activation of muscles responsible for flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction at the joint.

E. Special Movements:

These movements are typically specific to certain joints or body regions.

1. Elevation & 2. Depression

Elevation: Movement in a superior (upward) direction.

Scapula: Shrugging. Mandible: Closing mouth.

Muscles: Trapezius, Temporalis, Masseter.

Depression: Movement in an inferior (downward) direction.

Scapula: Lowering shoulders. Mandible: Opening mouth.

Muscles: Trapezius, Pectoralis minor, Platysma.

3. Protraction & 4. Retraction

Protraction (Protrusion): Anteriorly (forward) in the transverse plane.

Scapula: Rounding forward. Mandible: Jutting jaw forward.

Muscles: Serratus anterior, Pectoralis minor.

Retraction (Retrusion): Posteriorly (backward) in the transverse plane.

Scapula: Pulling back. Mandible: Pulling jaw backward.

Muscles: Rhomboids, Trapezius.

5. Dorsiflexion & 6. Plantarflexion

Dorsiflexion: Ankle joint; decreases angle between top of foot and anterior tibia (toes up).

Muscles: Tibialis anterior.

Plantarflexion: Ankle joint; increases angle between top of foot and anterior tibia (toes down/tiptoes).

Muscles: Gastrocnemius, Soleus.

7. Inversion & 8. Eversion

Inversion: Sole turns medially (inward).

Muscles: Tibialis anterior/posterior.

Eversion: Sole turns laterally (outward).

Muscles: Fibularis longus/brevis.

9. Pronation & 10. Supination (Forearm)

Pronation: Palm faces posteriorly (or inferiorly). Radius crosses ulna.

Muscles: Pronator teres/quadratus.

Supination: Palm faces anteriorly (anatomical position). Radius and ulna are parallel.

Muscles: Supinator, Biceps brachii.

11. Opposition & 12. Reposition

Opposition: Thumb across palm to touch tips of other fingers. Essential for grasping.

Muscles: Opponens pollicis.

Reposition: Thumb back to anatomical position.

13. Radial & 14. Ulnar Deviation

Radial Deviation (Abduction): Hand moves laterally towards thumb side.

Muscles: Flexor/Extensor carpi radialis.

Ulnar Deviation (Adduction): Hand moves medially towards little finger side.

Muscles: Flexor/Extensor carpi ulnaris.

- Range of Motion (ROM) Assessment: Clinicians assess ROM in various planes to diagnose injuries and track rehab.

- Gait Analysis: Understanding joint movements is crucial for analyzing walking patterns.

- Neurological Examination: Assessing specific movements helps localize neurological lesions.

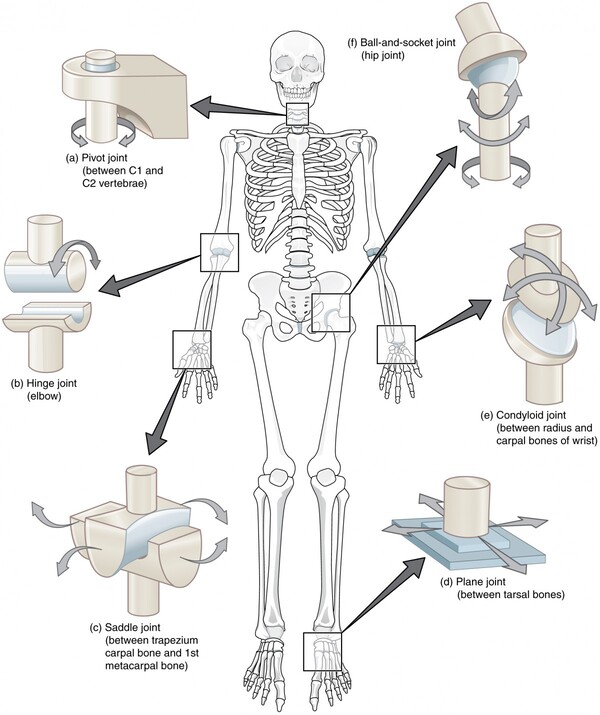

IV. Joint Structure and Its Influence on Movement

The design of a joint is the primary determinant of the range and types of motion. Synovial joint classification is based on the shape of articulating surfaces.

A. Functional Classification (Degrees of Freedom):

- Uniaxial: Movement in one plane around one axis (e.g., hinge, pivot).

- Biaxial: Movement in two planes around two axes (e.g., condyloid, saddle).

- Multiaxial: Movement in three or more planes around three or more axes (e.g., ball-and-socket).

B. Types of Synovial Joints and Their Movements:

| Joint Type | Structure & Movement | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Plane (Gliding) | Flat surfaces. Short, nonaxial gliding/slipping. Range: Very limited (stability). | Intercarpal, intertarsal, facet joints of vertebrae. |

| 2. Hinge | Cylindrical end in trough. Uniaxial (Sagittal). Primarily Flexion/Extension. | Elbow (humeroulnar), knee (modified), interphalangeal. |

| 3. Pivot | Rounded end in a sleeve/ring. Uniaxial (Vertical axis). Only Rotation. | Atlantoaxial (C1-C2), proximal radioulnar. |

| 4. Condyloid (Ellipsoidal) | Oval surface in oval depression. Biaxial (Flex/Ext and Abd/Add). Circumduction possible. | Radiocarpal (wrist), Metacarpophalangeal (2-5). |

| 5. Saddle | Complementary concave/convex areas. Biaxial. Allows opposition/reposition. | Carpometacarpal of the thumb. |

| 6. Ball-and-Socket | Spherical head in cup-like socket. Multiaxial. Freest range of motion in all planes. | Shoulder (glenohumeral), hip (acetabulofemoral). |

C. Factors Affecting Joint Mobility:

- Articular Cartilage: Smoothness reduces friction.

- Ligaments: Connect bones; provide stability and limit excessive movement.

- Joint Capsule: Encloses the joint, providing containment.

- Muscles and Tendons: Cross the joint; provide dynamic stability.

- Bony Anatomy: Shape can restrict movement (e.g., olecranon process limits elbow extension).

- Soft Tissue Apposition: Contact of soft tissues (e.g., muscle bulk) can limit movement.

- Genetics and Age: Individual variation and decreased elasticity impact flexibility.

V. Clinical Scenarios: Abnormal Movements and Range of Motion

Understanding normal movements is critical for identifying pathologies. Deviations from normal range or pain are significant indicators.

A. Limitations in Range of Motion (ROM):

1. Causes:

- Injury: Fractures, dislocations, sprains, strains.

- Inflammation: Arthritis (rheumatoid, osteoarthritis), bursitis, tendinitis.

- Scar Tissue/Fibrosis: Restricts movement post-trauma/surgery.

- Muscle Spasm/Tightness: Limits joint mobility.

- Neurological Conditions: Spasticity, rigidity, paralysis (e.g., stroke, spinal cord injury).

- Congenital Anomalies: Issues in joint formation.

- Pain: Often the primary limiting factor.

2. Clinical Assessment:

- Goniometry: Using a goniometer to objectively measure joint angles.

- Active ROM (AROM): Patient moves joint independently. Assesses strength/coordination.

- Passive ROM (PROM): Clinician moves the joint. Assesses integrity/restrictions.

- End-Feels: Sensation at the end of PROM (soft, firm, hard, empty).

B. Abnormal Movement Patterns:

- Compensation: Using alternative muscles/body parts due to weakness (e.g., elevating shoulder to assist arm abduction).

- Ataxia: Incoordination; staggering gait (cerebellar dysfunction).

- Dyskinesia: Involuntary, repetitive, bizarre movements.

- Tremor: Rhythmic, oscillatory movement.

- Spasticity/Rigidity:

- Spasticity: Velocity-dependent resistance ('clasp-knife').

- Rigidity: Non-velocity-dependent ('lead-pipe' or 'cogwheel').

- Flaccidity: Absence of muscle tone; limp limb.

C. Pathologies and Their Impact on Movement:

- Osteoarthritis: Degeneration leads to pain/stiffness (e.g., limited knee flexion).

- Rotator Cuff Tear: Impairs abduction and rotation.

- Ankle Sprain: Limits inversion/eversion; causes pain with weight-bearing.

- Stroke: Can lead to hemiparesis or hemiplegia.

- Scoliosis: Abnormal lateral curvature affecting trunk rotation.

VI. Utilizing Appropriate Anatomical Terminology

Accurate communication is paramount. Using precise terms avoids ambiguity.

A. Key Principles:

- Standard Anatomical Position: All descriptions default to this.

- Planes and Axes: Always specify both for complex motions.

- Paired Terms: Use opposing terms (Flex/Ext) for clarity.

- Specificity: Say "shoulder abduction" instead of "arm movement."

- Context: Mind the context (e.g., forearm pronation vs. foot pronation).

B. Practice and Application:

- Case Studies: Analyze scenarios and describe limitations.

- Peer Discussion: Intentionally use anatomical terms.

- Documentation: Use precise language in patient charts/reports.

Anatomical Movements

Test your knowledge with these 20 questions.

Anatomical Movements Quiz

Question 1/20

Quiz Complete!

Here are your results, .

Your Score

18/20

90%