Red blood Cell: Physiology

Red Blood Cells (Erythrocytes)

Red blood cells (RBCs), also known as erythrocytes, are arguably the most crucial component of blood in terms of overall physiological function. Their primary role is to transport oxygen from the lungs to the body's tissues and to transport carbon dioxide from the tissues back to the lungs. To efficiently carry out this vital function, RBCs possess a unique and highly specialized structure.

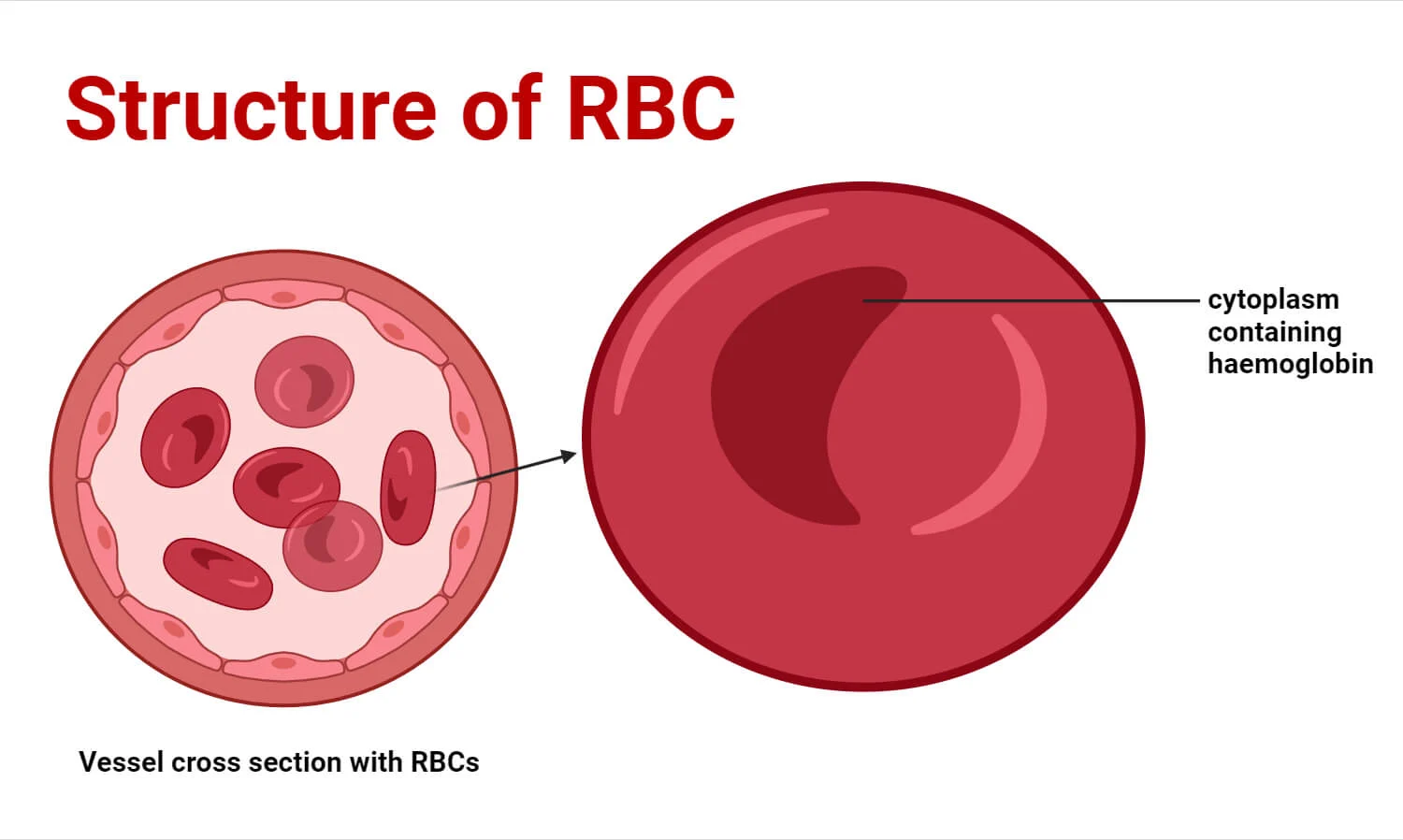

I. Structure of Red Blood Cells

1. Biconcave Disc Shape

Description: Mature RBCs are flexible, anucleated (lacking a nucleus), and lack most other organelles. Their most distinctive feature is their biconcave disc shape – a flattened disc with depressed centers on both sides.

Functional Significance:

- Increased Surface Area to Volume Ratio: Maximizes the surface area available for gas exchange (O2 and CO2). A spherical cell would have a much smaller surface area.

- Flexibility and Deformability: The biconcave shape and flexible membrane (maintained by a spectrin protein network) allow RBCs to bend and squeeze through narrow capillaries (3-4 µm) despite being 7.5 µm wide. Essential for circulation.

- Rouleaux Formation: Allows RBCs to stack like coins in single file to pass through narrow vessels without jamming.

2. Anucleated & Lack of Organelles

Description: Unlike most cells, mature RBCs extrude their nucleus and lose their mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi apparatus during maturation.

Functional Significance:

- Maximized Hemoglobin Content: Frees up space to be packed almost entirely with hemoglobin. Approx. 97% of the non-water content is hemoglobin.

- No Oxygen Consumption: Lacking mitochondria, RBCs do not consume the O2 they transport. They generate ATP primarily through anaerobic glycolysis.

- Limited Lifespan: Lack of protein synthesis machinery limits lifespan to approx. 100-120 days.

3. Plasma Membrane

Description: A phospholipid bilayer highly specialized with a dense network of cytoskeletal proteins (spectrin, ankyrin, band 3) on its inner surface.

Functional Significance:

- Maintain Shape and Flexibility: The spectrin-actin cytoskeleton provides structural integrity to withstand shear stress.

- Antigen Presentation: Displays glycoproteins and glycolipids (e.g., ABO and Rh antigens) important for blood typing.

II. Function of Red Blood Cells

1. Oxygen Transport

Mechanism: This is the primary function. Hemoglobin (Hb) binds reversibly to oxygen. Each Hb molecule binds up to four O2 molecules.

- Lungs: High O2 concentration → O2 loads onto Hb → Oxyhemoglobin (HbO2) (bright red).

- Tissues: Low O2 concentration → O2 unloads → diffuses into tissues.

Efficiency: High Hb concentration + large surface area = highly efficient transport.

2. Carbon Dioxide Transport

RBCs transport CO2 (waste product) via three methods:

Bicarbonate Buffer System (~70%)

Enzyme Carbonic Anhydrase converts CO2 + H2O → H2CO3 → H+ + HCO3-.

HCO3- moves to plasma (chloride shift) and acts as a buffer.

Carbaminohemoglobin (~20-23%)

CO2 binds directly to the globin protein (not heme iron).

Forms HbCO2.

Dissolved in Plasma (~7-10%)

Small amount of CO2 is simply dissolved in the fluid.

3. pH Regulation (Buffering)

Mechanism: Hemoglobin acts as a buffer. When CO2 is converted to H+ and HCO3-, the free H+ ions are buffered by deoxyhemoglobin. This prevents significant drops in intracellular pH.

Summary of Specializations

- Biconcave Shape: Surface area & flexibility.

- Anucleated: Max space for Hb, no O2 consumption.

- Packed with Hb: Gas transport vehicle.

- Carbonic Anhydrase: Facilitates CO2 transport & pH regulation.

- Flexible Membrane: Passage through capillaries.

Structure and Function of Hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (Hb) is the specialized protein within RBCs responsible for oxygen transport. It is a globular protein with a complex quaternary structure.

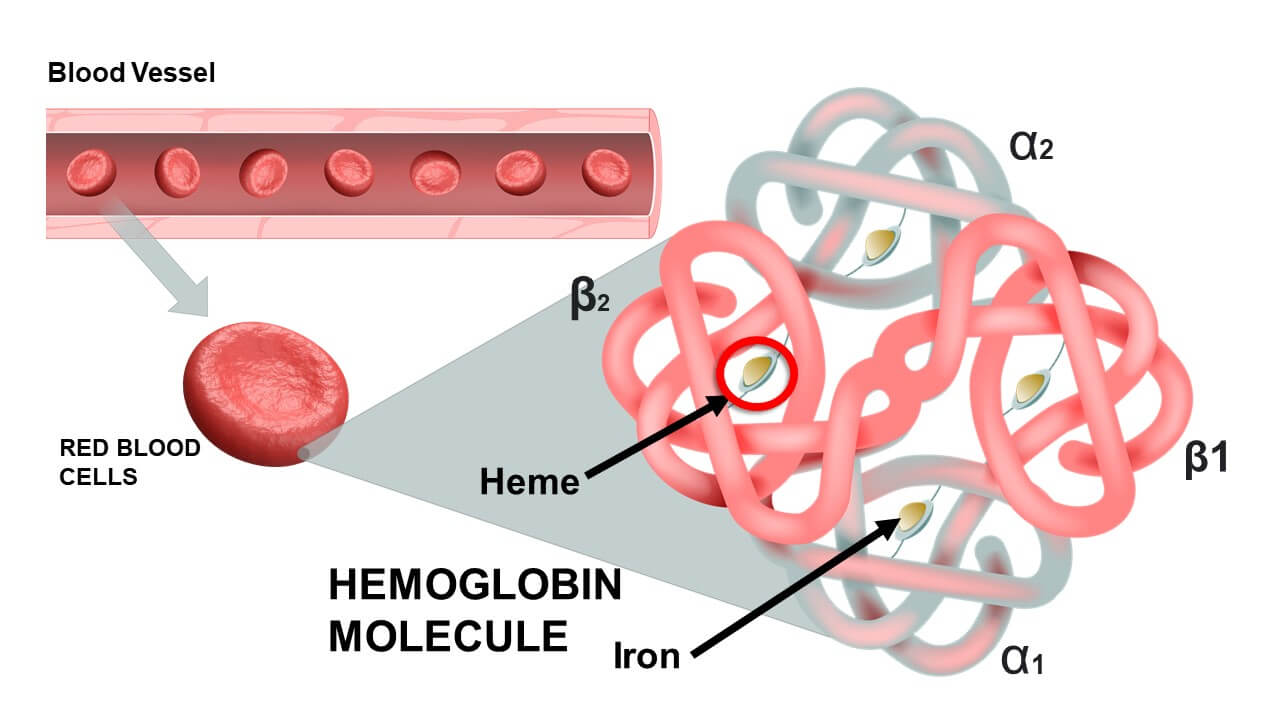

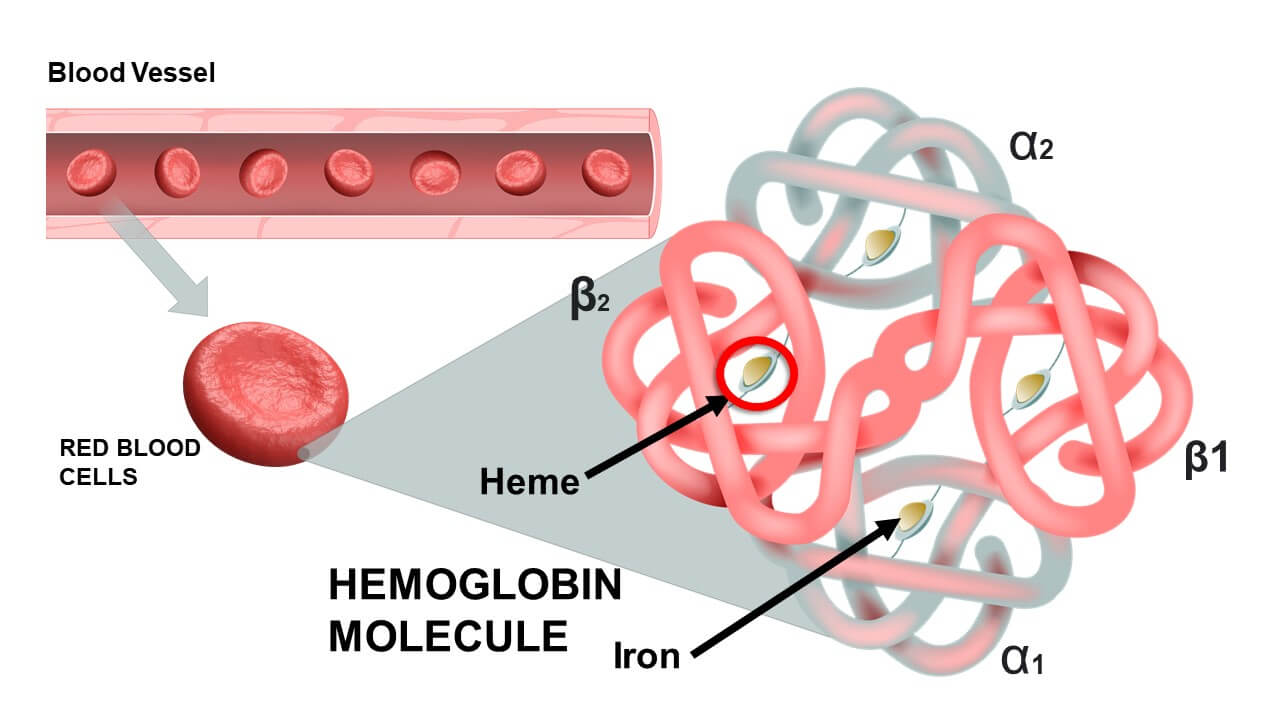

I. Structure of Hemoglobin

-

1. Four Polypeptide Chains (Globins):

Adult Hb (HbA) consists of two alpha (α) and two beta (β) chains.

-

2. Heme Groups:

Each globin chain has a non-protein heme group. One Hb molecule = 4 heme groups.

The Heme Group Detail:- Consists of a porphyrin ring with a central Iron Ion (Fe2+).

- Fe2+ (Ferrous): The critical site for O2 binding. Must be ferrous state; Ferric (Fe3+) state (methemoglobin) cannot bind oxygen.

- Capacity: One Hb molecule can bind up to 4 O2 molecules.

II. Function of Hemoglobin

A. Oxygen Transport (Primary)

- Oxygenation (Lungs): High PO2 → O2 binds to Fe2+ → Oxyhemoglobin (bright red).

- Deoxygenation (Tissues): Low PO2 → O2 released → Deoxyhemoglobin (dark red).

- Cooperative Binding: Binding of the first O2 changes the shape, increasing affinity for the next three. Release of one decreases affinity for the rest. This creates the sigmoidal oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve.

B. Carbon Dioxide Transport (Secondary)

- Carbaminohemoglobin: ~23% of CO2 binds to amino groups of globin chains. Reversible based on PCO2.

- Role in Bicarbonate System (Haldane Effect): Deoxyhemoglobin binds H+ ions (produced during bicarbonate formation). Deoxyhemoglobin has higher H+ affinity, preventing pH drop and facilitating CO2 uptake.

C. Buffering Blood pH

Deoxyhemoglobin acts as a buffer for H+ ions, helping maintain blood pH within the 7.35-7.45 range.

III. Types of Hemoglobin

HbA (Adult)

Structure: 2 Alpha (α), 2 Beta (β).

Prevalence: 95-98% of adult Hb.

HbA2 (Minor)

Structure: 2 Alpha (α), 2 Delta (δ).

Prevalence: 1.5-3.5%.

HbF (Fetal)

Structure: 2 Alpha (α), 2 Gamma (γ).

Function: Higher O2 affinity allows fetus to extract oxygen from maternal blood.

Clinical Relevance: Genetic defects in globin chains lead to hemoglobinopathies like Sickle Cell Anemia (beta chain mutation) and Thalassemias.

Structure and Function of Hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (Hb) is the specialized protein found within red blood cells responsible for their ability to transport oxygen and, to a lesser extent, carbon dioxide. It is a remarkable molecule whose structure is perfectly adapted for its vital role in gas exchange.

I. Structure of Hemoglobin

Hemoglobin is a globular protein with a complex quaternary protein structure.

1. Four Polypeptide Chains (Globins)

A single hemoglobin molecule is composed of four protein subunits, or globin chains.

- In adults, the most common type (HbA) consists of two alpha (α) chains and two beta (β) chains.

- Each globin chain has a specific amino acid sequence and a characteristic folded structure.

2. Heme Groups

Each of the four globin chains is associated with a non-protein, iron-containing prosthetic group called a heme group.

(Therefore: 1 Hemoglobin molecule = 4 Heme groups).

The Heme Group Detail:

- Porphyrin Ring: A large organic molecule structure.

-

Iron Ion (Fe2+): A central ferrous iron ion is chelated within the ring.

Critical Function: This Fe2+ is the binding site for oxygen. Each iron can bind one O2 molecule. -

Reversible Binding: The bond is weak and reversible.

Important: Iron must be in the Ferrous (Fe2+) state. If oxidized to Ferric (Fe3+), it forms methemoglobin and cannot bind oxygen.

II. Function of Hemoglobin

1. Oxygen Transport (Primary Function)

Oxygenation (Lungs)

In the lungs (High PO2):

- Oxygen diffuses into RBCs.

- Binds to Fe2+ in heme.

- Forms Oxyhemoglobin (HbO2).

- Appearance: Bright Red.

Deoxygenation (Tissues)

In tissues (Low PO2):

- Oxygen bond breaks.

- Oxygen diffuses into tissue cells.

- Becomes Deoxyhemoglobin (HHb) (or reduced hemoglobin).

- Appearance: Darker, dull red.

Concept: Cooperative Binding

Hemoglobin exhibits a unique phenomenon where the binding of oxygen facilitates further binding.

- When the first O2 molecule binds to one heme group, it causes a conformational (shape) change in the entire hemoglobin molecule.

- This change increases the affinity of the remaining three heme groups for oxygen.

- Conversely, when one O2 is released, it decreases the affinity of the others, facilitating further release.

Result: The characteristic S-shaped (sigmoidal) oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve, allowing for highly efficient loading in lungs and unloading in tissues.

2. Carbon Dioxide Transport (Secondary Function)

Hemoglobin aids in CO2 transport via two mechanisms:

-

Carbaminohemoglobin (HbCO2):

About 20-23% of blood CO2 binds directly to the amino groups of the globin chains (NOT the heme iron). This is reversible based on PCO2 levels. -

Role in Bicarbonate System (Haldane Effect):

While Hb doesn't transport bicarbonate directly, it buffers the Hydrogen ions (H+) produced during the conversion of CO2 to bicarbonate. Deoxyhemoglobin binds these H+ ions, preventing a pH drop and facilitating more CO2 uptake.

3. Buffering Blood pH

Role of Deoxyhemoglobin: It acts as a stronger buffer for H+ ions than oxyhemoglobin. By binding H+ generated from carbonic acid, hemoglobin helps maintain blood pH within the narrow physiological range (7.35-7.45).

III. Types of Hemoglobin

Types vary based on the composition of their globin chains.

Hemoglobin A (HbA)

Structure:

2 Alpha (α) + 2 Beta (β) chains (α2β2).

Prevalence:

Most common adult type (95-98%).

Hemoglobin A2 (HbA2)

Structure:

2 Alpha (α) + 2 Delta (δ) chains (α2δ2).

Prevalence:

Minor adult type (1.5-3.5%).

Hemoglobin F (HbF)

Structure:

2 Alpha (α) + 2 Gamma (γ) chains (α2γ2).

Prevalence:

Primary fetal hemoglobin.

Has higher O2 affinity than HbA to extract oxygen from mom.

Clinical Relevance

Genetic defects affecting globin chains can lead to hemoglobinopathies, such as Sickle Cell Anemia (mutation in beta chain) and Thalassemias (reduced synthesis of alpha or beta chains), which severely impair oxygen transport.

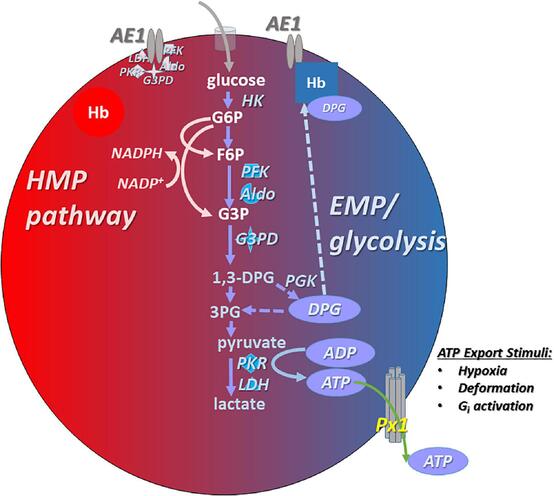

Metabolic Pathways of Red Blood Cells

Mature red blood cells are unique among human cells due to their lack of a nucleus, mitochondria, and other organelles. This distinct cellular composition dictates a highly specialized and simplified metabolic machinery, primarily focused on maintaining cell integrity and the functionality of hemoglobin.

I. Lack of Mitochondria and Aerobic Respiration

Consequence: Since RBCs lack mitochondria, they cannot perform oxidative phosphorylation, the highly efficient process of ATP generation that uses oxygen.

Significance: This is a crucial adaptation. If RBCs used the oxygen they transport for their own energy needs, it would significantly reduce the efficiency of oxygen delivery to the tissues.

II. Primary Energy Production: Anaerobic Glycolysis

Pathway: Glycolysis is the sole pathway for ATP production in mature RBCs. This process breaks down glucose (obtained from the plasma) into pyruvate, ultimately producing a net gain of 2 ATP molecules per molecule of glucose.

End Product: Pyruvate is then converted to lactate (lactic acid) because, in the absence of mitochondria and an electron transport chain, pyruvate cannot enter the Krebs cycle or oxidative phosphorylation. Lactate is released into the plasma and can be taken up by the liver for gluconeogenesis (Cori cycle).

Functional Significance of ATP:

Maintenance of Ion Gradients: ATP powers the Na+/K+-ATPase pump, which actively transports sodium out of the cell and potassium into the cell. This maintains the osmotic balance and prevents the cell from swelling and bursting (hemolysis).

Maintenance of Biconcave Shape: ATP is required to maintain the spectrin-actin cytoskeleton, which supports the biconcave shape and deformability of the RBC.

Other Metabolic Reactions: ATP is also needed for various other minor metabolic reactions and the phosphorylation of certain substrates.

III. The Pentose Phosphate Pathway (Hexose Monophosphate Shunt - HMP Shunt)

Purpose: This pathway, while not producing ATP, is absolutely critical for protecting the red blood cell from oxidative damage.

Key Product: The HMP shunt generates NADPH (Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate, reduced form).

Mechanism of Protection:

- Role of NADPH: NADPH is essential for reducing oxidized glutathione (GSSG) back to its reduced form (GSH) via the enzyme glutathione reductase.

- Glutathione (GSH): Reduced glutathione is a potent antioxidant within the RBC.

- Glutathione Peroxidase: GSH is then used by the enzyme glutathione peroxidase to neutralize harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), by converting them into water.

Significance: Without a functioning HMP shunt and sufficient NADPH, RBCs are highly susceptible to oxidative stress (e.g., from certain drugs, infections, or environmental toxins). Oxidative damage can lead to:

- Denaturation of Hemoglobin: Formation of Heinz bodies (precipitated hemoglobin) which can damage the cell membrane.

- Membrane Damage: Leads to increased membrane rigidity and fragility.

- Premature Hemolysis: Oxidatively damaged RBCs are prematurely destroyed, leading to hemolytic anemia.

Clinical Relevance: Genetic deficiencies in enzymes of the HMP shunt, such as Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, are common and can lead to severe hemolytic anemia when individuals are exposed to oxidative stressors (e.g., fava beans, certain antimalarial drugs, sulfonamides, or infections).

IV. The Rapoport-Luebering Shunt (2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate Pathway)

Purpose: This side branch of glycolysis is unique to RBCs and does not produce ATP. Instead, it produces 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG or 2,3-DPG).

Role of 2,3-BPG: 2,3-BPG binds to deoxyhemoglobin (Hb without O2), causing a conformational change that decreases hemoglobin's affinity for oxygen.

Significance:

- Oxygen Release in Tissues: Higher levels of 2,3-BPG promote the release of oxygen from hemoglobin to the tissues, which is particularly important at high altitudes or in conditions of hypoxia.

- Inverse Relationship with Oxygen Affinity: The higher the concentration of 2,3-BPG, the more readily hemoglobin releases oxygen (i.e., decreased oxygen affinity). Conversely, lower 2,3-BPG levels increase oxygen affinity (e.g., in stored blood, which has low 2,3-BPG, making it less effective at oxygen delivery until its 2,3-BPG levels are restored).

- Fetal Hemoglobin (HbF): HbF has a lower affinity for 2,3-BPG than adult hemoglobin (HbA). This means HbF has a higher affinity for oxygen, allowing the fetus to effectively extract oxygen from the mother's blood (which has HbA and higher 2,3-BPG levels).

V. Methemoglobin Reductase Pathway (NADH-dependent)

Purpose: This pathway is critical for maintaining the iron in hemoglobin in its functional ferrous (Fe2+) state.

Key Enzyme: Methemoglobin reductase (also known as diaphorase I) uses NADH (generated from glycolysis) to reduce ferric iron (Fe3+) back to ferrous iron (Fe2+).

Significance: Oxidizing agents can convert the ferrous iron (Fe2+) in hemoglobin to ferric iron (Fe3+), forming methemoglobin. Methemoglobin cannot bind oxygen, thus reducing the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. This pathway continuously works to reverse this process.

Clinical Relevance: Deficiency in methemoglobin reductase or excessive exposure to oxidizing agents can lead to methemoglobinemia, where a significant portion of hemoglobin is in the Fe3+ state, resulting in a bluish discoloration of the skin (cyanosis) and impaired oxygen delivery.

Summary of RBC Metabolic Pathways and Their Functions:

- Anaerobic Glycolysis: Produces ATP for ion pumps and membrane integrity.

- Pentose Phosphate Pathway (HMP Shunt): Produces NADPH to protect against oxidative damage via glutathione.

- Rapoport-Luebering Shunt: Produces 2,3-BPG to regulate oxygen affinity of hemoglobin.

- Methemoglobin Reductase Pathway: Maintains hemoglobin iron in the ferrous (Fe2+) state for oxygen binding.

Erythropoiesis and the Destruction of Red Blood Cells

The life cycle of a red blood cell is a carefully orchestrated process, from its formation in the bone marrow to its eventual destruction after about 120 days. This continuous turnover ensures a constant supply of functional RBCs for oxygen transport.

I. Erythropoiesis (Red Blood Cell Production)

Erythropoiesis is the specific term for the formation of red blood cells. It is a tightly regulated process that occurs primarily in the red bone marrow of adults.

Stimulus

The primary stimulus for erythropoiesis is hypoxia (insufficient oxygen delivery to the tissues).

- Kidney as Sensor: The kidneys act as the main sensors of blood oxygen levels. When renal cells detect hypoxia, they release the hormone erythropoietin (EPO).

- Other Factors: Other factors that can stimulate EPO release include significant blood loss, high altitude, and intense exercise.

Role of Erythropoietin (EPO)

- Target Cells: EPO circulates in the blood and travels to the red bone marrow, where it acts on hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) that have committed to the erythroid lineage.

- Effects: EPO stimulates:

- Increased rate of cell division: Accelerates the proliferation of erythrocyte progenitor cells.

- Accelerated maturation: Speeds up the differentiation process through various developmental stages.

- Increased hemoglobin synthesis: Promotes the production of hemoglobin within the developing cells.

- Premature release of reticulocytes: In times of severe demand, the bone marrow may release reticulocytes slightly earlier than usual.

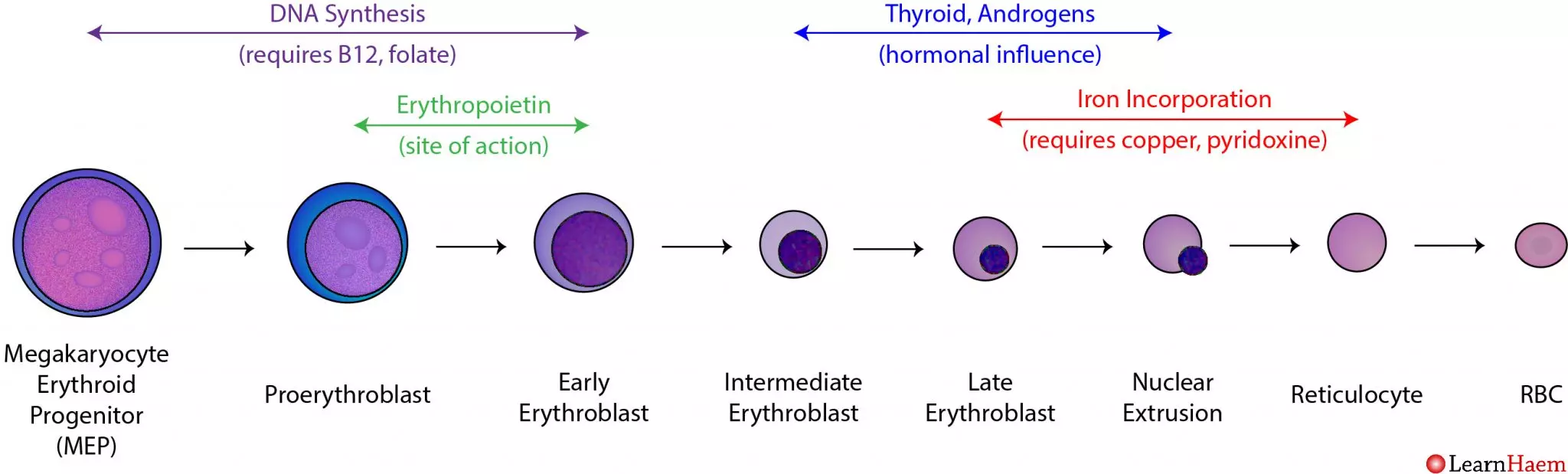

Stages of Erythropoiesis (from Hematopoietic Stem Cell to Mature RBC)

The ultimate precursor, found in red bone marrow.

HSC differentiates into a CMP, which can give rise to various myeloid cells, including red blood cells.

The first committed cell in the erythroid lineage. It is large, basophilic (stains blue due to ribosomes), and actively synthesizes proteins for future divisions.

Divides rapidly, accumulating ribosomes for future hemoglobin synthesis.

Hemoglobin synthesis begins, leading to a mixed blue-pink (polychromatic) staining pattern. Cell division continues.

Hemoglobin accumulation is nearly complete, and the cytoplasm is predominantly pink (eosinophilic). The nucleus becomes dense and pyknotic (condensed) and is then ejected from the cell. This is the last nucleated stage.

Anucleated but still contains residual ribosomal RNA (mRNA and ribosomes), which gives it a fine, reticular (net-like) appearance with special stains. Reticulocytes are released from the bone marrow into the peripheral blood. They mature into erythrocytes within 1-2 days. The reticulocyte count is a good indicator of the rate of effective erythropoiesis.

After losing its residual RNA, the reticulocyte becomes a fully functional, biconcave disc, packed with hemoglobin.

Nutritional Requirements for Erythropoiesis

- Iron: Essential for hemoglobin synthesis (part of the heme group). Iron is absorbed from the diet, transported by transferrin, and stored as ferritin in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow.

- Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin) and Folate (Folic Acid): Crucial for DNA synthesis, particularly for the rapid cell division of erythrocyte precursors. Deficiencies lead to impaired DNA synthesis and maturation defects, resulting in large, immature red blood cells (megaloblastic anemia).

- Amino Acids: Required for the synthesis of the globin protein chains.

II. Destruction of Red Blood Cells

Mature RBCs have a lifespan of approximately 100-120 days. Due to their lack of a nucleus and organelles, they cannot repair themselves. Over time, their membranes become rigid and fragile, and their enzymatic activity declines.

Phagocytosis by Macrophages

Location: Senescent (aged) or damaged RBCs are primarily removed from circulation by specialized macrophages (phagocytes) in the:

- Spleen ("red blood cell graveyard"): The spleen's narrow capillaries (sinusoids) act as a filter, trapping old, inflexible RBCs.

- Liver: Also contains macrophages (Kupffer cells) that participate in RBC breakdown.

- Bone Marrow: Macrophages here also recycle old RBCs.

Breakdown of Hemoglobin

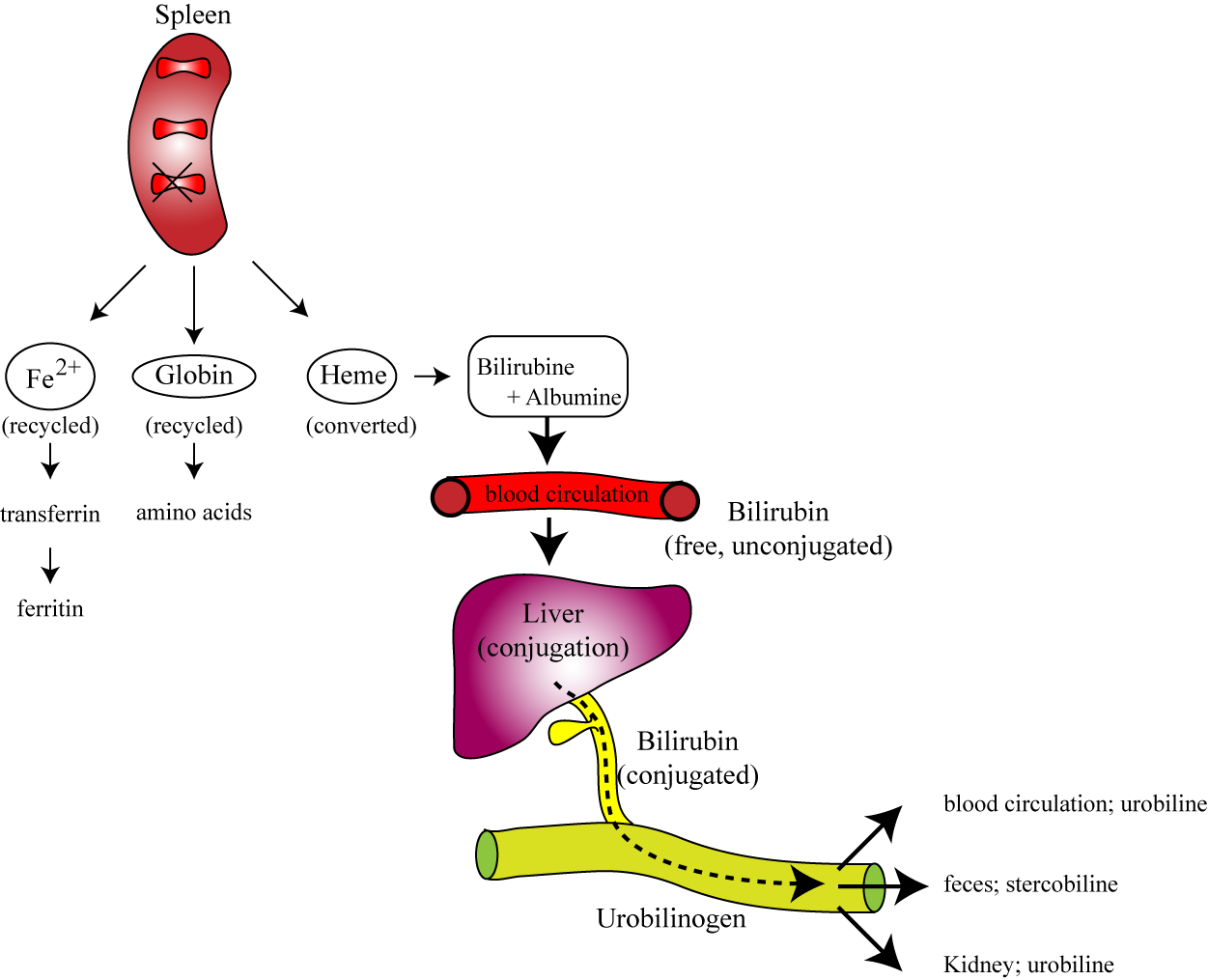

Once phagocytosed, the red blood cell is broken down, and its components are recycled:

1. Globin Chains

The protein globin chains are catabolized into their constituent amino acids. These amino acids are then returned to the amino acid pool in the blood and can be reused for synthesizing new proteins, including new globin chains for erythropoiesis.

2. Heme Group

The heme group is separated from globin and further broken down:

A. Iron (Fe): The iron is salvaged. It binds to a transport protein called transferrin and is transported back to the bone marrow to be reused for new hemoglobin synthesis, or it is stored as ferritin or hemosiderin in the liver and spleen.

B. Porphyrin Ring (without Iron): The porphyrin ring is degraded into a yellowish pigment called biliverdin, which is then quickly reduced to bilirubin.

- Unconjugated (Indirect) Bilirubin: Bilirubin is insoluble in water, so it binds to albumin in the blood and is transported to the liver.

- Conjugated (Direct) Bilirubin: In the liver, bilirubin is conjugated (made water-soluble) with glucuronic acid.

- Excretion: Conjugated bilirubin is then excreted by the liver into the bile, which passes into the small intestine.

- Urobilinogen & Stercobilin: In the intestine, bacteria metabolize bilirubin into urobilinogen. Some urobilinogen is reabsorbed and excreted in urine (giving urine its yellow color), but most is oxidized to stercobilin, which gives feces its characteristic brown color.

Jaundice: An accumulation of bilirubin in the blood (hyperbilirubinemia), often due to excessive RBC destruction (hemolytic anemia) or liver dysfunction (impaired bilirubin processing/excretion), leads to a yellowing of the skin and sclera of the eyes, a condition known as jaundice.

Summary of Erythrocyte Life Cycle:

- Birth (Erythropoiesis): Stimulated by EPO (from kidneys) in response to hypoxia. Occurs in red bone marrow. Involves a series of developmental stages from HSC to reticulocyte to mature erythrocyte. Requires iron, B12, and folate.

- Circulation: Mature RBCs circulate for ~120 days, transporting O2 and CO2.

- Death (Destruction): Aged RBCs become rigid and are phagocytosed by macrophages, primarily in the spleen, liver, and bone marrow.

- Recycling: Hemoglobin components are broken down: globin to amino acids, iron salvaged, and heme converted to bilirubin for excretion.

Red Blood Cells Quiz

Test your knowledge with these 35 questions.

Red Blood Cells Quiz

Question 1/35

Quiz Complete!

Here are your results, .

Your Score

33/35

94%